The Impact of Organizational Support, Environmental Health Literacy on Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Rural Living Environment Improvement in China: Exploratory Analysis Based on a PLS-SEM Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

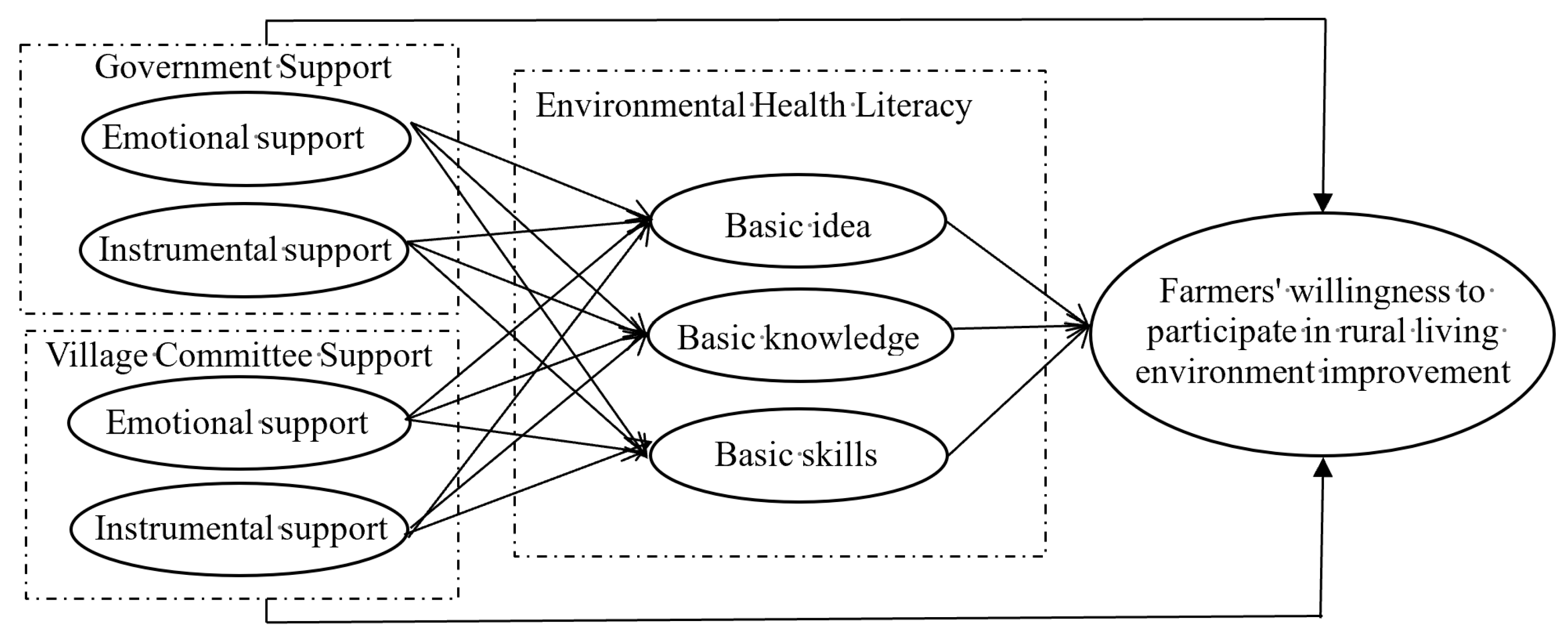

2. Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Organizational Support and Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Rural living Environment Improvement

2.1.1. Impact of Government Support on Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Improving Living Environment

2.1.2. Impact of Village Committee Support on Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Improving Living Environment

2.2. Relationship between Environmental Health Literacy and the Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Improving their Living Environment

2.3. Mediating Role of Environmental Health Literacy

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Methods

| Statistical Indicators | Jiangsu | Gansu | Total | Statistical Indicators | Jiangsu | Gansu | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 313 | 291 | 604 | Age | <18 | 1 | 119 | 120 |

| Male | 227 | 394 | 621 | 18–25 | 16 | 16 | 32 | ||

| Education level | Illiterate | 8 | 18 | 26 | 26–30 | 41 | 18 | 59 | |

| Know some words | 13 | 23 | 36 | 31–40 | 114 | 101 | 215 | ||

| Primary Schools | 91 | 122 | 213 | 41–50 | 131 | 271 | 402 | ||

| Junior high school | 223 | 243 | 466 | 51–60 | 153 | 118 | 271 | ||

| High School | 160 | 231 | 391 | >60 | 84 | 42 | 126 | ||

| University and graduate students | 45 | 48 | 93 | Household expenditure (Unit: RMB 10,000) | <1 | 2 | 62 | 64 | |

| Resident status | Village officials | 6 | 24 | 6 | 1–3 | 239 | 292 | 531 | |

| Villagers’ representatives | 0 | 15 | 0 | 3–6 | 104 | 220 | 324 | ||

| Communist Party member | 24 | 54 | 24 | 6–10 | 139 | 84 | 223 | ||

| General villagers | 510 | 592 | 510 | >10 | 56 | 27 | 83 | ||

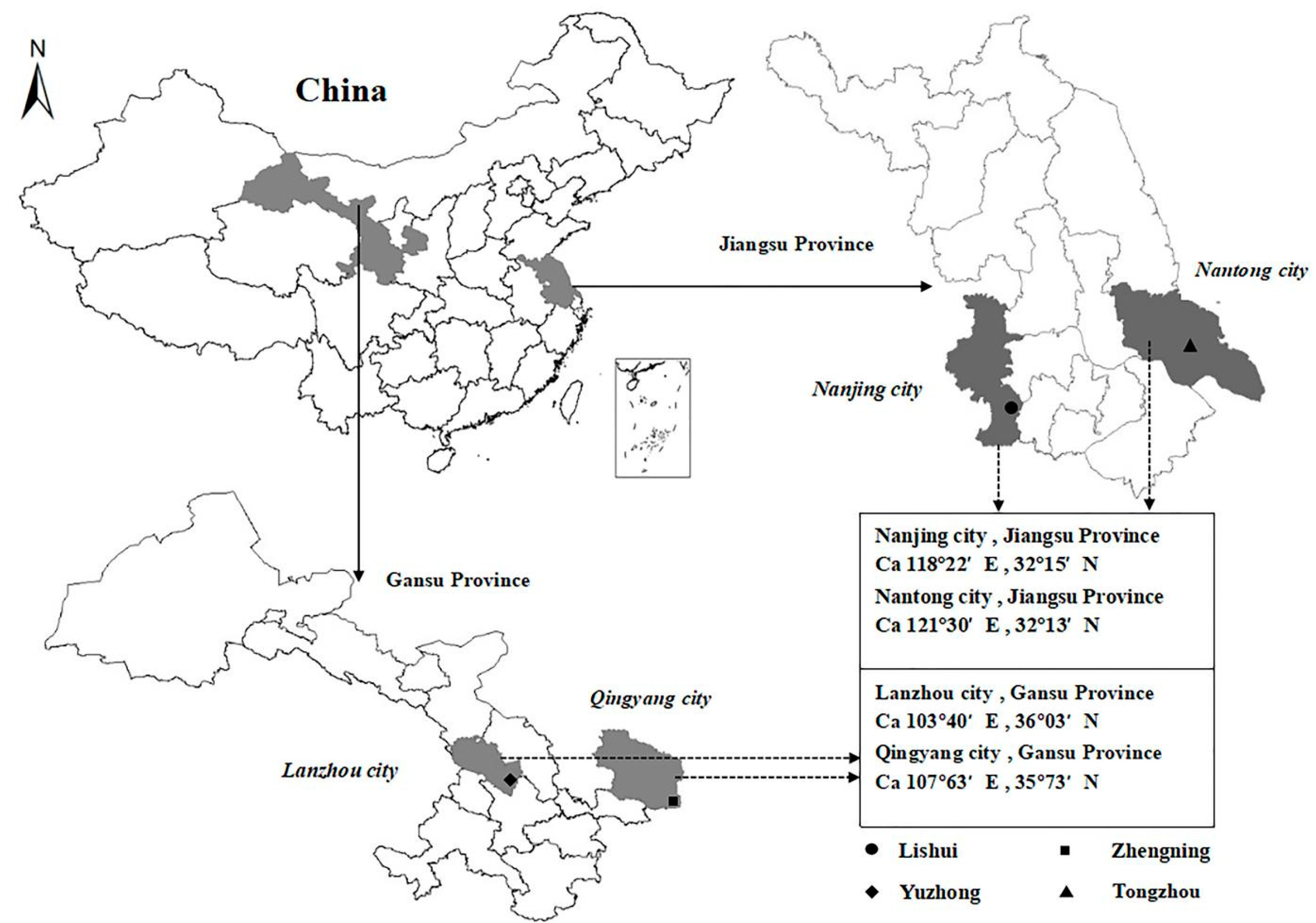

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Variable Selection

3.3.1. Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Rural Living Environment Improvement

3.3.2. Organizational Support

3.3.3. Environmental Health Literacy

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Estimation

4.1.1. Validity Test

4.1.2. Covariances Diagnosis

4.2. Model Goodness of Fit Test

4.3. Estimation of the Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison with Literature

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Li, H. Interdisciplinary Governance of Agricultural Environmental Pollution: Conflicts and Resolution. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Hu, X. Rural Space Transition in Western Countries and Its Inspiration. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2019, 39, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Q. The Main Theoretical Evolution and Enlightenment of Western Rural Geography Since 1990s. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2020, 40, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, C. The Post-productivist Countryside: A Theoretical Perspective of Rural Revitalization. China Rural Surv. 2018, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, C.; Tilzey, M. Agricultural policy discourses in the European post-Fordist transition: Neoliberalism, neomercantilism and multifunctionality. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2005, 29, 581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A. From productivism to post-productivism… and back again? Exploring the (un) changed natural and mental landscapes of European agriculture. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2001, 26, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Yang, S. The Environmental Health Regulatory System: Experience of the Unite States. Chin. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 10, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, Y. The construction system and response strategy of urban and rural “safe and healthy units”: Thinking on the response mechanism of “prevention-adaptation-use” for epidemic and disaster. Urban Plan. 2020, 44, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Li, H. Analysis of rural habitat management paths in the post-epidemic era from the perspective of villagers’ perceptions and willingness to respond. J. Agric. For. Econ. Manag. 2020, 19, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ren, J. Moving towards the Targeted Governance:The New Start of China’s Agricultural and Rural Development in the Post Well-off Era. J. Public Manag. 2022, 19, 1–11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L. The Development Characteristics of Belgian Rural Area in Post-Productivism Era, its Mechanism and Enlightenment to China’s Rural Planning. Dev. Small Cities Towns 2019, 37, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Deepening reform and releasing the endogenetic energy for rural revitalization. Dong Yue Trib. 2018, 39, 133–139, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, H. Public goods provision in rural China: Post-reform changes. Reform 1996, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Cao, J. Key Measures on the Dilemma of Poverty Alleviation in Coordination with Rural Vitalization. Issues Agric. Econ. 2022, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Crafting Institutions for Self-Governing Irrigation Systems; ICS Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-1-55815-168-0. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W. Effectiveness of public service provision in rural living environment and its influencing factors in China—Based on the perspective of farmers. China Rural Econ. 2014, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Wang, S. The Model Evolution and Modern Transformation of Rural Community Governance since the Founding of New China. Jiang-Huai Trib. 2021, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S. The Practical Development of Citizen Participation in Contemporary Western Local Governance and Its Implications. Adm. Trib. 2015, 22, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Lu, Q.; Xu, T. Analysis of factors influencing willingness to cooperate in supplying small rural water facilities: Based on a multi-group structural equation model. Rural Econ. 2016, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Njoh, A.J. Municipal councils, international NGOs and citizen participation in public infrastructure development in rural settlements in Cameroon. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liu, N.; Chen, L. An Analysis of Farmers’ Collective Inaction in Rural Environmental Governance and Its Turning Logic. China Rural Surv. 2021, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, B.; Li, G.; Feng, Z. Did Off—Farm Farmer Shouldn’t Get Agricultural Subsidy? Concurrent Comments on the Method of Subsidy Payment after the “Three Agricultural Subsidy” Reform. Issues Agric. Econ. 2021, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Li, D.; Chen, J. Farmers’ Participation in Cooperative Economic Organizations and Cro Regional Non-agricultural Employment:Empirical Analysis Based on Endogenous Transformation Probit Model. World Agric. 2022, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Shu, Q. Labor Out-migration, Rural Collective Action and Rural Revitalization. J. Tsinghua Univ. 2022, 37, 173–187, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yao, S. Rural Public Space and Collective Action in the Period of Social Transition: An Examination of Farmers’ Cooperative Participation Behavior in the Centralized Treatment of Rural Domestic Waste in Xingyang, Henan Province. Theory Reform 2016, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Chen, H.; Yu, Z.; Xiao, W.; Tan, Y. What Drives Farmers to Participate in Rural Environmental Governance? Evidence from Villages in Sandu Town, Eastern China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Research on villagers’ participation in rural habitat improvement based on community capacity perspective. Rural Econ. 2020, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Jakus, P.; Tiller, K.; Park, W. Explaining Rural Household Participation in Recycling. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 1997, 29, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaffou, M.; Chahlaoui, A.; Sadki, M.; Maliki, A.; Khaffou, M.; Belghyti, D. Sustainable Sanitation: An Appropriate Solution in Rural Areas. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 1090, p. 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Hou, L.; Min, S.; Huang, J. The Effects of Rural Living Environment Improvement Programs: Evidence from a Household Survey in 7 Provinces of China. J. Manag. World 2021, 37, 182–195, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhao, M. The influence of environmental concern and institutional trust on farmers’ willingness to participate in rural domestic waste treatment. Resour. Sci. 2019, 41, 1500–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, W. Analysis of farmers’ willingness of involvement in rural domestic sewage treatment. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H. Research on the Garbage Classification Behavior in the Improvement of Rural Habitat Environment: Based on the Survey Data from Sichuan Province. J. Southwest Univ. Sci. Ed. 2020, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, A.; Abdul Rahim, K.; Shamsudin, M.N.; Shuib, A. The Willingness to Pay for Better Environment: The Case of Pineapple Cultivation on Peat Soil in Samarahan, Sarawak.; School of Social Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia: Penang, Malaysia, 2012; pp. 635–645. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.; Fujiwara, A.; Zhang, J.; Kuwano, M. Measurement of Willingness to Pay of Street Environment Improvement Based on Uncertainty. Proc. East. Asia Soc. Transp. Stud. 2003, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; He, K.; Tong, Q.; Liu, Y. Study on Participation Behavior of Rural Residents Living Garbage Cooperative Governance: An Analysis Based on Psychological Perception and Environmental Intervention. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2019, 28, 459–468. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Li, S.; Nan, L. Farming households’ pro-environmental behaviors from the perspective of environmental literacy. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 856–869. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, B. Family Livelihood Capital, the Recognition and the Behavior of Paying for the Governance of Rural Living Environment for Farmers: Taking 873 Farmers in Jiangxi Province for Example. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2021, 20, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Wang, X.B.; Hou, L.L.; Huang, J.K. The Determinants of Farmers’ Participation in Rural Living Environment Improvement Programs: Evidence from Mountainous Areas in Southwest China. China Rural Surv. 2019, 148, 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, W.; Yang, F.; Wang, Y. Farmers’ Participation in Improving Living Environment from the Perspective of Environmental Literacy. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2021, 20, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Research on the Influencing Mechanism of Farmers’ Pro-Environmental Behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhongnan University of Economic and Law, Wuhan, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Noreau, L.; Boschen, K. Intersection of participation and environmental factors: A complex interactive process. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, S44–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Yao, S. Ecological perceptions, government subsidies and farmers’ willingness to participate in rural habitat improvement. Stat. Inf. Forum 2021, 36, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifegbesan, A.P.; Rampedi, I.T.; Odumosu, T. Residents’ participation and perception of environmental sanitation program in Ogun East Senatorial District, Nigeria: A mixed-method approach. Int. J. Environ. Waste Manag. 2022, 29, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, M. Public Participation in Environmental Decision Making in India: A Critique. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2017, 22, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Fang, K.; Liu, T. Impact of social norms and public supervision on the willingness and behavior of farming households to participate in rural living environment improvement: Empirical analysis based on generalized continuous ratio model. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 2354–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Luo, X.; Yu, W. Migrant Work Experience, Institutional Constraints and Farmers’ Willingness to Pay for Environmental Governance. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2021, 21, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S. Problems and Countermeasures of Citizen Participation in Local Governance. Mod. Bus. Trade Ind. 2020, 41, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, G.; Annibal, I.; Carroll, T.; Price, L.; Sellick, J.; Shepherd, J. Empowering Local Action through Neo-Endogenous Development; The Case of LEADER in England. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Hu, Y. Multiple Logic in Success and Failure of Industrial Poverty Alleviation a Their Combination. Rural Econ. 2020, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, X. Differential Atmosphere, Organizational Support, and Willingness of Farmers’ Cooperation: A Survey Based on Construction, Administration and Maintenance of Small Scale Conservancy Facilities. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2015, 15, 87–97, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, Y. Influence of social capital and organizational support on performance of farmers’ participation in the management and maintenance of small-scale farmland water conservancy. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2018, 28, 148–156. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, Y. Influence of social trust and organizational support on the performance of farmers’ participation in the management and maintenance of small-scale farmland water conservancy. Resour. Sci. 2018, 40, 1230–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Kong, X.; Wang, B. A study on farmers’ cognition, institutional environment, and farmers’ willingness to participate in habitat improvement: The mediating effect of information trust. Arid Zone Resour. Environ. 2021, 35, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. On Factors Influencing the Original Residents’ Willingness to Participate in Green Low: Carbon Construction in Xiong’an New Area: A Study Based on 387 Original Residents Survey Data. J. Xiangtan Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2020, 44, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, J.; Xia, X. How Can Resource-poor Villages Achieve Endogenous Development: Based on the Road for Rural Construction of Village D in the Western Region. Issues Agric. Econ. 2021, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived Organizational Support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, R.C. Customer Satisfaction and Organizational Support for Service Providers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. Chinese Knowledge-workers’ Perceived Organizational Support and Its Influence on Their Job Performance and Turnover Intention. Ph.D. Thesis, Huazhong University of Science & Technology, Wuhan, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y. The Significance and Valuable Experience of Agricultural Tax Reform. Peoples Trib. 2021, 78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, H. The Role of Government in the WTO Framework: Collective Action and Effective Government. In Proceedings of the WTO and Government Response, Beijing, China, 16 May 2002; Institute of Political Development and Government Management, Peking University (Key Research Base of Political Science, Ministry of Education); School of Government Management, Peking University: Beijing, China, 2002; pp. 69–77. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CPFD&dbname=CPFD0914&filename=BDZF200205001009&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=J7dC7FOJIDq6xBirx81wP2sZqsnptNdpPl-AcOfuSFE5JqqcVXMBC2UwE3opKI5JuPoAqiFinLA%3d (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Ding, Z.; Wang, J. Seventy Years of Rural Governance in China: Historical Evolution and Logical Path. China Rural Surv. 2019, 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Liu, S. Rural Governance and Rural Revitalization: Historical Changes, Problems and Reform Deepening. Fujian Trib. 2021, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Wang, L.; Lu, Q. Farmers’ cognition, government support and farmers’ soil and water conservation technology adoption in Loess Plateau. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2019, 33, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, H.; Xue, C.; Yao, S. Study on the influence of government support on farmer’s greenproduction knowledge under the adjustment of farmer’s differentiation. J. Northwest AF Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2019, 19, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. Can Inclusive Institutions Promote Public Governance in Rural Areas? An Empirical Analysis Based on the Relationship between Agricultural Tax Reform and Village Irrigation Investment. J. Manag. World 2022, 38, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ding, N. On the construction of online communication on citizens’ environmental literacy—Taking Sina.com air pollution report as an example. J. Beijing Union Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2016, 14, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potipiroon, W.; Ford, M.T. Relational costs of status: Can the relationship between supervisor incivility, perceived support, and follower outcomes be exacerbated? J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 92, 873–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Long, J. Changes of Rural Basic Management System Since the Founding of the Communist Party of China. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2021, 68, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D.; Fan, Y. Public environmental knowledge measurement: A proposal and test of a local scale. J. Renmin Univ. China 2016, 30, 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, D. Stakeholder involvement and public participation: A critique of Water Framework Directive arrangements in the United Kingdom. Water Environ. J. 2008, 22, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Xie, K. The Influencing Factors of Farmers’ Waste Classification and Disposal Behavior Based on the Lewin’s Behavior Model. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 36, 186–190, 204. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Hou, A.; Yu, Y.; Hu, C.; Liang, S. Analysis of factors influencing environmental health literacy of residents in Hubei Province. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 43, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y. Research on the influence of institutional trust on farmers’ willingness to participate in environmental governance decisions. Soft Sci. 2019, 33, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ma, J. Work value and motivation mediate the influence of personality on contextual performance. J. Zhejiang Univ. Ed. 2014, 41, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, W.L. Republics, Passions and Protests. In Philosophical Perspectives on Democracy in the 21st Century; Cudd, A.E., Scholz, S.J., Eds.; AMINTAPHIL: The Philosophical Foundations of Law and Justice; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 5, pp. 229–239. ISBN 978-3-319-02311-3. [Google Scholar]

- Paço, A.; Lavrador, T. Environmental knowledge and attitudes and behaviours towards energy consumption. J. Environ. Manage. 2017, 197, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to Pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M. Environmental knowledge and conservation behavior: Exploring prevalence and structure in a representative sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 37, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Lu, J. Participation in Rural Development. China Rural Surv. 2002, 52–60, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M. Structural Equation Modeling—Manipulation and Application of AMOS, 2nd ed.; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2018; ISBN 978-7-5624-5720-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Yu, J. The impact of risks and opportunities on multidimensional poverty of farmers in ecologically vulnerable areas: An analysis based on a structural equation model with formative indicators. China Rural Surv. 2019, 64–80. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Dou, X.; Li, J.; Cai, L. Analyzing government role in rural tourism development: An empirical investigation from China. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 79, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Bu, S. A Critical Review on Rural Vitalization Studies. J. China Agric. Univ. Sci. 2022, 39, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publshing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-5443-9640-8. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.; Ketchen, D.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common Beliefs and Reality About Partial Least Squares: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, F. A statistical survey on the demand for rural environmental protection public goods and its influencing factors. Stat. Decis. 2019, 35, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. Effects of Policy Instruments and Perceived Value on Farmers’ Home Waste Management: Waste-Sorting Behaviours. Ph.D. Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Yang, H. Study on the behavior mechanism of farmers’ participation in property right adjustment in Land Consolidation. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2017, 131, 108–116, 148–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Raju, S.; Laczniak, R.N. The Roles of Gratitude and Guilt on Customer Satisfaction in Perceptions of Service Failure and Recovery. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2021, 14, 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Lin, P.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. An analysis of the behavioral decisions of governments, village collectives, and farmers under rural waste sorting. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 95, 106780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X. Interpersonal Trust, Institutional Trust and Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Environmental Governance: The example of agricultural waste resourcing. J. Manag. World 2015, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, C. The role of governments in promoting rural households’ willingness to participate in rural environmental governance: Guidance or behavior demonstration. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2021, 35, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Reisner, A. Factors influencing private and public environmental protection behaviors: Results from a survey of residents in Shaanxi, China. J. Environ. Manage. 2011, 92, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matiiuk, Y.; Liobikienė, G. The impact of informational, social, convenience and financial tools on waste sorting behavior: Assumptions and reflections of the real situation. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 297, 113323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. The Involution of Rural Reform and Its Decipherment in the Context of Rural Revitalization: A Perspective of “Control Right” Theory. Lanzhou Acad. J. 2020, 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Bakardjieva, M. From Networked Individualism to Collective Action: Understanding Mobilisation in a New Media Environment. In Proceedings of the ECPR Joint Sessions Mainz, Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz, Mainz, Germany, 11–16 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, R.; Lin, X. Promoting Integrated Development of Rural and Urban Areas amid the Revitalization Strategy: Implications and Lessons from Main Develope Countries. Int. Econ. Rev. 2022, 155–173, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Woods, M. Rural Restructuring Under Globalization in Eastern Coastal China: What Can be Learned From Wales? J. Rural Commun. Dev. 2011, 6, 70–94. [Google Scholar]

| Variable Name and Question Item | Assignment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers’ willingness to participate in living environment improvement program (WP) | Very reluctant = 1; Reluctant = 2; Fairly = 3; Willing = 4; Very willing = 5. | ||

| WWS | Are you willing to sort your household waste? | ||

| WWC | Are you willing to throw garbage at a fixed location, such as a garbage container? | ||

| WRS | Are you willing to reduce the discharge of domestic sewage? | ||

| WDS | Are you willing to separate the discharge of domestic sewage? | ||

| WRT | Are you willing to carry out sanitary toilet renovation? | ||

| Organizational support | |||

| Government support | |||

| Performance of local government departments in living environment improvement. | |||

| Government emotional support (GES) | Not at all = 1; Not quite get to = 2; General = 3; Almost there = 4; Exactly equal to = 5 | ||

| GES1 | a. Fair and reasonable distribution of remediation materials | ||

| GES2 | b. Fair selection of beautiful villages, model villages, etc. | ||

| GES3 | c. Try to solve the difficulties encountered in environmental management in the region | ||

| Government instrumental support (GIS) | |||

| GIS1 | d. Try to provide funds and the required infrastructure and equipment | ||

| GIS2 | e. Responsible for environmental management and providing technical guidance | ||

| GIS3 | f. Publicize environmental regulation norms through posters and public numbers | ||

| GIS4 | g. Township government department staff to inspect the township | ||

| Villages Committee Support | |||

| Performance of village committee departments in living environment improvement. | |||

| Village committee emotional support (VES) | Not at all = 1; Not quite get to = 2; General = 3; Almost there = 4; Exactly equal to = 5 | ||

| VES1 | a. Can respect the rights and interests of each person and value individual opinions | ||

| VES2 | b. Care about the needs of villagers and provide assistance | ||

| VES3 | c. act according to rules and regulations and do not seek personal gain | ||

| Village committee instrumental support (VIS) | |||

| VIS1 | d. Promote relevant knowledge and skills through radio and WeChat groups | ||

| VIS2 | e. Set the requirements and the time and personnel arrangement of activities | ||

| VIS3 | f. Organize and mobilize villagers to make their yards and public areas hygiene | ||

| VIS4 | g. Supervise the environmental behavior of villagers and carry out hygiene evaluation | ||

| Environmental health literacy (EHL) | |||

| Do you agree with the following statements? | |||

| EHI1 | a. Clear water and green mountains are important guarantees for health | Strongly disagree = 1; Disagree = 2; General = 3; Agree = 4; Strongly agree = 5 | |

| EHI2 | b. Rural garbage and sewage and village appearance need to be treated | ||

| EHI3 | c. The village environment can be destroyed as long as the income can be improved * | ||

| EHI4 | d. The village sanitary environment depends on the consciousness of each person | ||

| EHI5 | e. Farmers participate in living environment remediation more efficiently than the government | ||

| EHK1 | f. Children, pregnant women, and the elderly are more sensitive to harmful factors. | ||

| EHK2 | g. Extreme weather has directly affected human life and health | ||

| EHK3 | h. Heart and lung diseases may be acquired in a seriously polluted place for a long time | ||

| EHK4 | i. Rational disposal of domestic waste is good for health and environmental protection | ||

| EHK5 | j. Burning garbage and dumping sewage pollute the environment and increase health risks | ||

| EHS1 | k. Reduce going out or wearing masks in heavy pollution and dust storms | ||

| EHS2 | l. Learn and master how to separate household garbage | ||

| EHS3 | m. Learn about environmental information in their location through TV and the internet | ||

| EHS4 | n. Have the ability to report to the relevant authorities if a company damages the environment | ||

| Potential Variables | Observations Variables | Weights | Potential Variables | Observations Variables | Weights | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiangsu | Gansu | All Samples | Jiangsu | Gansu | All Samples | ||||

| GES | GES1 | 0.448 *** | 0.430 *** | 0.428 *** | VES | VES1 | 0.531 *** | 0.411 *** | 0.469 *** |

| GES2 | 0.457 *** | 0.448 *** | 0.447 *** | VES2 | 0.346 *** | 0.335 *** | 0.334 *** | ||

| GES3 | 0.334 *** | 0.449 *** | 0.406 *** | VES3 | 0.400 *** | 0.424 *** | 0.405 *** | ||

| GIS | GIS1 | 0.503 *** | 0.511 *** | 0.517 *** | VIS | VIS1 | 0.135 ** | 0.236 *** | 0.196 *** |

| GIS2 | 0.179 *** | 0.169 *** | 0.171 *** | VIS2 | 0.266 *** | 0.233 *** | 0.234 *** | ||

| GIS3 | 0.313 *** | 0.304 *** | 0.296 *** | VIS3 | 0.124 ** | 0.303 *** | 0.226 *** | ||

| GIS4 | 0.336 *** | 0.232 *** | 0.262 *** | VIS4 | 0.682 *** | 0.427 *** | 0.550 *** | ||

| EHI | EHI1 | 0.352 *** | 0.274 *** | 0.299 *** | EHS | EHS1 | 0.397 *** | 0.327 *** | 0.351 *** |

| EHI2 | 0.299 *** | 0.325 *** | 0.294 *** | EHS2 | 0.271 *** | 0.252 *** | 0.256 *** | ||

| EHI3 | 0.261 *** | 0.330 *** | 0.280 *** | EHS3 | 0.333 *** | 0.255 *** | 0.284 *** | ||

| EHI4 | 0.130 ** | 0.130 *** | 0.162 *** | EHS4 | 0.297 *** | 0.346 *** | 0.327 *** | ||

| EHI5 | 0.255 *** | 0.123 | 0.185 *** | WP | WWS | 0.137 *** | 0.175 *** | 0.167 *** | |

| EHK | EHK1 | 0.473 *** | 0.205 *** | 0.325 *** | WWC | 0.285 *** | 0.253 *** | 0.259 *** | |

| EHK2 | 0.314 *** | 0.244 *** | 0.310 *** | WRS | 0.300 *** | 0.224 *** | 0.255 *** | ||

| EHK3 | 0.174 *** | 0.174 *** | 0.151 *** | WDS | 0.150 *** | 0.208 *** | 0.176 *** | ||

| EHK4 | 0.232 *** | 0.206 *** | 0.194 *** | WRT | 0.301 *** | 0.274 *** | 0.287 *** | ||

| EHK5 | 0.128 *** | 0.337 *** | 0.240 *** | ||||||

| Cross-Loadings | WP | EHS | GIS | GES | VIS | VES | EHI | EHK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIS1 | 0.518 | 0.490 | 0.550 | 0.457 | 0.736 | 0.562 | 0.479 | 0.434 |

| VIS2 | 0.546 | 0.532 | 0.582 | 0.507 | 0.777 | 0.607 | 0.489 | 0.463 |

| VIS3 | 0.543 | 0.524 | 0.578 | 0.506 | 0.768 | 0.601 | 0.489 | 0.449 |

| VIS4 | 0.628 | 0.601 | 0.630 | 0.559 | 0.910 | 0.645 | 0.602 | 0.549 |

| GIS1 | 0.633 | 0.593 | 0.881 | 0.580 | 0.614 | 0.612 | 0.564 | 0.522 |

| GIS2 | 0.509 | 0.471 | 0.694 | 0.460 | 0.484 | 0.497 | 0.435 | 0.402 |

| GIS3 | 0.555 | 0.512 | 0.778 | 0.497 | 0.595 | 0.570 | 0.516 | 0.459 |

| GIS4 | 0.522 | 0.507 | 0.744 | 0.478 | 0.551 | 0.544 | 0.505 | 0.417 |

| EHS1 | 0.712 | 0.863 | 0.577 | 0.608 | 0.572 | 0.579 | 0.699 | 0.618 |

| EHS2 | 0.643 | 0.778 | 0.507 | 0.552 | 0.507 | 0.529 | 0.625 | 0.546 |

| EHS3 | 0.656 | 0.819 | 0.561 | 0.589 | 0.581 | 0.570 | 0.675 | 0.599 |

| EHS4 | 0.660 | 0.815 | 0.552 | 0.592 | 0.535 | 0.562 | 0.678 | 0.608 |

| EHI1 | 0.655 | 0.637 | 0.526 | 0.578 | 0.531 | 0.522 | 0.814 | 0.568 |

| EHI2 | 0.663 | 0.698 | 0.554 | 0.599 | 0.552 | 0.552 | 0.836 | 0.631 |

| EHI3 | 0.611 | 0.623 | 0.506 | 0.553 | 0.500 | 0.513 | 0.770 | 0.592 |

| EHI4 | 0.677 | 0.677 | 0.518 | 0.579 | 0.527 | 0.533 | 0.828 | 0.624 |

| EHI5 | 0.668 | 0.705 | 0.549 | 0.603 | 0.538 | 0.540 | 0.837 | 0.608 |

| EHK1 | 0.616 | 0.622 | 0.492 | 0.542 | 0.512 | 0.542 | 0.620 | 0.861 |

| EHK2 | 0.606 | 0.604 | 0.501 | 0.511 | 0.506 | 0.534 | 0.607 | 0.842 |

| EHK3 | 0.544 | 0.551 | 0.443 | 0.480 | 0.465 | 0.494 | 0.567 | 0.767 |

| EHK4 | 0.567 | 0.588 | 0.476 | 0.524 | 0.469 | 0.512 | 0.610 | 0.806 |

| EHK5 | 0.566 | 0.576 | 0.456 | 0.469 | 0.469 | 0.480 | 0.592 | 0.778 |

| VES1 | 0.609 | 0.584 | 0.614 | 0.558 | 0.612 | 0.849 | 0.548 | 0.535 |

| VES2 | 0.561 | 0.528 | 0.550 | 0.499 | 0.598 | 0.786 | 0.515 | 0.502 |

| VES3 | 0.594 | 0.576 | 0.595 | 0.518 | 0.630 | 0.836 | 0.547 | 0.523 |

| GES1 | 0.583 | 0.549 | 0.516 | 0.783 | 0.493 | 0.524 | 0.565 | 0.490 |

| GES2 | 0.577 | 0.548 | 0.482 | 0.776 | 0.482 | 0.474 | 0.563 | 0.481 |

| GES3 | 0.579 | 0.578 | 0.528 | 0.781 | 0.499 | 0.498 | 0.542 | 0.483 |

| WGC | 0.871 | 0.706 | 0.617 | 0.645 | 0.627 | 0.635 | 0.692 | 0.635 |

| WGP | 0.895 | 0.735 | 0.630 | 0.658 | 0.587 | 0.630 | 0.734 | 0.642 |

| WRS | 0.869 | 0.699 | 0.631 | 0.653 | 0.635 | 0.618 | 0.697 | 0.607 |

| WDS | 0.852 | 0.707 | 0.613 | 0.643 | 0.616 | 0.607 | 0.662 | 0.593 |

| WRT | 0.877 | 0.715 | 0.631 | 0.647 | 0.593 | 0.630 | 0.701 | 0.644 |

| Statistical Test Volume | Jiangsu | Gansu | All Samples | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRMR | d_G | NFI | SRMR | d_G | NFI | SRMR | d_G | NFI | |

| Adaptive criteria or critical values | <0.08 | <0.95 | >0.9 | <0.08 | <0.95 | >0.9 | <0.08 | <0.95 | >0.9 |

| Test results | 0.042 | 0.306 | 0.913 | 0.061 | 0.327 | 0.933 | 0.051 | 0.242 | 0.943 |

| Model fitness judgment | acceptable | Adaptation | acceptable | Good | acceptable | acceptable | Good | acceptable | acceptable |

| Variables | R2 (R2adj) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Jiangsu | Gansu | All Samples | |

| WP | 0.792 (0.789) | 0.762 (0.760) | 0.777 (0.775) |

| EHI | 0.609 (0.606) | 0.593 (0.590) | 0.602 (0.601) |

| EHK | 0.552 (0.549) | 0.473 (0.470) | 0.495 (0.493) |

| EHS | 0.597 (0.594) | 0.634 (0.632) | 0.628 (0.626) |

| Effectiveness | Path | Jiangsu | Gansu | All Samples | Effectiveness | Path | Jiangsu | Gansu | All Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | GES -> EHI | 0.414 *** | 0.384 *** | 0.410 *** | Indirect effects | GES -> EHI -> WP | 0.071 *** | 0.088 *** | 0.088 *** |

| GES -> EHK | 0.323 *** | 0.295 *** | 0.299 *** | GES -> EHK -> WP | 0.028 ** | 0.032 *** | 0.029 *** | ||

| GES -> EHS | 0.434 *** | 0.334 *** | 0.374 *** | GES -> EHS -> WP | 0.108 *** | 0.095 *** | 0.100 *** | ||

| GIS -> EHI | 0.220 *** | 0.095 ** | 0.154 *** | GIS -> EHI -> WP | 0.037 *** | 0.022 ** | 0.033 *** | ||

| GIS -> EHK | 0.137 *** | 0.052 | 0.099 *** | GIS -> EHK -> WP | 0.012 * | 0.006 | 0.010 ** | ||

| GIS -> EHS | 0.167 *** | 0.131 *** | 0.163 *** | GIS -> EHS -> WP | 0.042 *** | 0.037 *** | 0.044 *** | ||

| VES -> EHI | 0.162 *** | 0.160 *** | 0.158 *** | VES -> EHI -> WP | 0.028 *** | 0.037 *** | 0.034 *** | ||

| VES -> EHK | 0.271 *** | 0.261 *** | 0.264 *** | VES -> EHK -> WP | 0.023 ** | 0.028 *** | 0.025 *** | ||

| VES -> EHS | 0.162 *** | 0.235 *** | 0.208 *** | VES -> EHS -> WP | 0.040 *** | 0.067 *** | 0.056 *** | ||

| VIS -> EHI | 0.100 ** | 0.236 *** | 0.163 *** | VIS -> EHI -> WP | 0.017 ** | 0.054 *** | 0.035 *** | ||

| VIS -> EHK | 0.127 *** | 0.171 *** | 0.141 *** | VIS -> EHK -> WP | 0.011 * | 0.019 ** | 0.014 *** | ||

| VIS -> EHS | 0.121 *** | 0.207 *** | 0.162 *** | VIS -> EHS -> WP | 0.030 *** | 0.059 *** | 0.043 *** | ||

| GES -> WP | 0.236 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.158 *** | Total effect | GES -> WP | 0.442 *** | 0.299 *** | 0.375 *** | |

| GIS -> WP | 0.117 *** | 0.149 *** | 0.126 *** | GIS -> WP | 0.208 *** | 0.214 *** | 0.212 *** | ||

| VES -> WP | 0.106 *** | 0.106 *** | 0.095 *** | VES -> WP | 0.197 *** | 0.238 *** | 0.211 *** | ||

| VIS -> WP | 0.078 ** | 0.039 | 0.059 ** | VIS -> WP | 0.136 *** | 0.170 *** | 0.151 *** | ||

| EHI -> WP | 0.170 *** | 0.230 *** | 0.216 *** | ||||||

| EHK -> WP | 0.086 ** | 0.109 *** | 0.096 *** | ||||||

| EHS -> WP | 0.249 *** | 0.283 *** | 0.268 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Ding, X.; Li, D.; Li, S. The Impact of Organizational Support, Environmental Health Literacy on Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Rural Living Environment Improvement in China: Exploratory Analysis Based on a PLS-SEM Model. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1798. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111798

Wang J, Ding X, Li D, Li S. The Impact of Organizational Support, Environmental Health Literacy on Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Rural Living Environment Improvement in China: Exploratory Analysis Based on a PLS-SEM Model. Agriculture. 2022; 12(11):1798. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111798

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jing, Xiang Ding, Dongjian Li, and Shiping Li. 2022. "The Impact of Organizational Support, Environmental Health Literacy on Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Rural Living Environment Improvement in China: Exploratory Analysis Based on a PLS-SEM Model" Agriculture 12, no. 11: 1798. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111798

APA StyleWang, J., Ding, X., Li, D., & Li, S. (2022). The Impact of Organizational Support, Environmental Health Literacy on Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Rural Living Environment Improvement in China: Exploratory Analysis Based on a PLS-SEM Model. Agriculture, 12(11), 1798. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111798