Abstract

An individual’s expectations for the value of farmland are a manifestation of his or her awareness of farmland rights and interests. Differences between male and female farmers in their use of farmland, employment, education, and rights protection may ultimately lead to differences in the evaluation of land value between the two groups. Clarifying such gender differences in the valuation of farmland and the reasons for them is of great significance for the formulation of policies and scientific research in areas such as the protection of rural women’s rights, nonagricultural employment, and land transfer. In the context of the global “feminization of agriculture”, we start with individuals’ psychological expectations for the value of farmland. We use data on farmland from the 2015 China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) and estimate an OLS regression model. The moderating effects model identifies the impact of gender differences on such expectations and the underlying mechanism. We find that (1) rural female farmers’ psychological expectations for the value of farmland are much lower than those of males due to their disadvantages in receiving information through policy publicization and their greater willingness to transfer into nonagricultural employment, and (2), according to the heterogeneity analysis, better educated female farmers and those living in areas with greater economic and social development expect farmland to be more valuable. These conclusions show that female farmers are currently less aware of their economic rights in rural China than male farmers, and that education, policy propaganda, and economic and social underdevelopment hinder their awareness of women’s rights. We propose policy suggestions to ensure women’s educational rights, promote the adjustment of the industrial structure and of policy propaganda, and balance regional economic and social development.

1. Introduction

Since Pierce proposed the concept of the “feminization of poverty” in 1978, and as the proportion of women engaged in agricultural production and management has continued to increase, the “feminization of agriculture” has gradually become more frequently emphasized and discussed by researchers [1,2,3]. The feminization of agriculture is a salient feature of agricultural management as traditional agricultural societies transform into modern industrial societies and is an important social and economic phenomenon in the early and middle stages of urbanization. Currently, this feminization has become a global phenomenon [2]. This phenomenon is particularly widespread in today’s developing countries, such as China, Nepal, India, Bangladesh, most countries and regions in Latin America, and those African countries that are still dominated by agriculture. Three aspects of this phenomenon—its meaning, characteristics, and practical effects—have received extensive attention from researchers [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11].

Women play an important role in agricultural production and management. Aggregate data show that women comprise approximately 43% of the agricultural labour force globally and in developing countries [12]. Women produce between 60 and 80% of food in most developing countries and are responsible for half of the world’s food production [13]. According to estimates by the World Bank in 2014, women accounted for 42% to 65% of Kenyan agricultural operations [14]. In short, women play an important role in agricultural labour supply, land distribution, food production, and other fields [13,14,15]. However, despite this important role in agriculture, in many developing countries, women still lack opportunities to participate in cooperative organizations [16], and they are also frequently ignored by policies [17]. In addition, the feminization of agriculture has emerged as a trend in some developed countries. For example, in 2001, the percentage of full-time workers in the German agricultural sector who were women increased from 36% to 44%, and female representation in part-time agricultural jobs increased from 60% to 65% [17], which definitively shows the trend of feminization in Germany. The feminization of agriculture is mainly due to two effects: the “suction” generated by the high demand for labour in the urban industrial and commercial sectors and the “push” generated by the surplus of labour in the rural agricultural sector. These two effects have driven a large number of rural male labourers to transfer from the agricultural sector to the industrial and commercial sectors. Because this labour transfer is incomplete, agricultural business activities are mainly conducted by female workers, and even some families have been completely “feminized” [18,19,20,21,22,23].

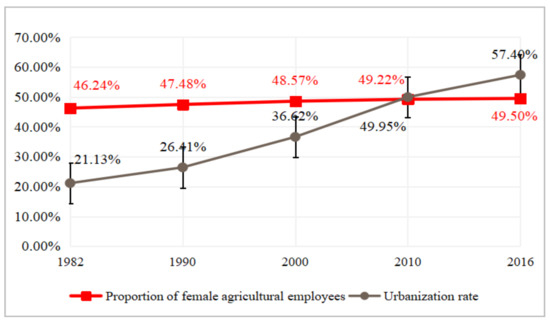

China is the world’s largest developing country, and it is steadily becoming increasingly urbanized. At present, China’s agricultural production and management processes are becoming aged and feminized, and this transition is precisely the result of the transfer of male and young workers to nonagricultural sectors [19,22,24,25,26,27]. In 1978, after China implemented its reform and opening policy and began to vigorously promote urbanization, a large number of male labourers transferred to nonagricultural employment in pursuit of higher industrial [4] and commercial wages. During this process, due to the inherent characteristics of the rural female labour force and the constraints of the urban–rural household registration system, the possibility of transferring into nonagricultural employment has been much lower for women than for men, resulting in a large number of female labourers staying in rural areas and engaging in agricultural production and business activities [5]. For example, according to data released by the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, in 2017, there was a total of 171.85 million migrant workers from rural areas, of which only 31.3% were female (see Table A1 1.1). Figure 1 shows the changes in China’s urbanization rate and in the percentage of female agricultural workers from 1982 to 2016. If calculated, according to the 2010 population gender distribution, 51.27% male and 48.73% female, the total number of female agricultural workers surpassed males as early as 2010, indicating that female farmers became the majority in agricultural production and management in approximately 2010 (see Table A1 1.2). According to a survey conducted in the three Chinese provinces of Shandong, Jiangsu, and Liaoning, women in these three provinces are the mainstay of agricultural production and management, and even the percentage of labourers in the three provinces who are female has reached approximately 60% [28,29,30]. In terms of the gender ratio for agricultural workers, China’s agricultural production and operations entered into an era of absolute feminization in approximately 2010, and this feminization has been further strengthened as urbanization has continued to progress.

Figure 1.

Changes in the urbanization rate and the proportion of female agricultural employees (1982–2016).

The feminization of agriculture, brought about by the transfer of male labour to nonagricultural employment, has at least the following three characteristics: (1) It has led to the transformation of women’s economic roles as traditional agriculture has transformed into modern agriculture [31], thereby affecting the division of labour within the family; (2) It has changed how agricultural production and operations are conducted, for example, by increasing the agricultural machinery or agricultural machinery services being adopted [24,26] as well as changing who the agricultural management decision-makers are [29,32] and changing the efficiency of agricultural output. These impacts of agricultural feminization on agricultural production efficiency have been established through recent empirical findings, but they are controversial. For example, some empirical researchers have found that the feminization of agriculture has not reduced the level of output or the efficiency of agriculture [23,25,32,33,34,35,36,37]. However, other researchers have found that the feminization of agriculture has somewhat reduced the efficiency of agricultural production, especially the extent to which agricultural technology contributes to efficiency [38,39,40]. (3) It has changed the emotional relationships and the information asymmetry regarding farmland between males and females. In short, the feminization of agriculture has caused female farmers to rely more on farmland for employment, reduced the information asymmetry regarding farmland between males and females, and improved the power of female farmers to make decisions about agricultural operations.

Therefore, given the feminization of agriculture, do female farmers expect farmland to be more valuable than male farmers do? If so, what is the mechanism driving the differential expectations? If not, what factors have prevented there from being a difference in expectations between female farmers and male farmers regarding the value of farmland? In addition, what are the heterogeneities among female farmers? However, the existing research has mainly analysed the context, actual outcomes, and impact of agricultural feminization [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Research on the value of farmland has also focused on the specific valuations of farmland and their determinants [41,42,43,44,45]. No researchers have explored, against the crucial background of the feminization of agriculture, the gender differences in expectations for farmland value, the heterogeneity among female farmers and the mechanisms underlying their effects, or the full impact of other factors that affect farmers’ expectations for farmland value. Analysing the differences in psychological decision-making about farmland value between male farmers and female farmers against the background of the feminization of agricultural and the determinants of those differences, as well as other factors that affect farmers’ expectations for farmland value, is conducive to understanding the heterogeneity in men and women’s economic decision-making behaviours and farmland value expectations. Developing a logical framework is also conducive to analysing the gender differences in expectations regarding the value of farmland and to discovering the factors that affect the differences in the perceptions of rights and interests between men and women.

On this basis, and on the basis of previous studies, our study uses cross-sectional survey data on rural residents from the 2015 China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) and draws on the basic principles of four theories: expectancy–value theory and planned behaviour theory (PBT) from the psychology of motivation, asymmetric information theory, and human capital theory. Cultivated land is used to represent farmland, and a linear probability model and moderating effects model are used. We evaluate the differences between genders in a farmer’s farmland value expectations, the heterogeneity among females, and the channels that lead to the observed differences. In addition, we also evaluate the impact of other factors on farmers’ farmland value expectations. The goal of our study is to provide references for the formulation of government-level women’s rights protection policies, nonagricultural employment policies, and farmland transfer policies, as well as for other researchers’ research on agricultural feminization, rural household land transfers, and women’s rights protection.

Compared with previous studies, the marginal contribution of this article lies in the following: first, it uses national-level survey data to explore the heterogeneity by gender in farmers’ expectations for farmland value through horizontal comparisons; second, it considers heterogeneity along three dimensions: the women’s individual internal and subjective characteristics, the characteristics of their families, and their local regions; and third, it further explores the channels that lead to the observed gender differences in farmland value expectations.

2. Theoretical Analysis Framework and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Theoretical Analysis Framework

Expected value theory and planned behaviour theory were first proposed by Atkinson (Atkinson JW) and Ike Ajzen (Icek Ajzen) [46,47], the two main researchers on the characteristics of, and factors that influence, individual behavioural decision-making (including psychological behaviours). The theory of information asymmetry was researched by George Akerlov, Michael Spencer, and Joseph Stiglitz in the 1970s. This theory mainly analyses the differences in behaviour caused by differences in the amount of information available to different subjects engaging in market economic activities. Human capital theory mainly addresses the formation of human capital and its impact on output efficiency [48]. We analyse the logic underlying the formation of farmers’ farmland value expectations and the corresponding factors of influence through the basic principles of expected value theory and planned behaviour theory, and we use the basic principles of information asymmetry theory and human capital theory to analyse the role of gender in determining the channels by which farmland value expectations are formed, thereby establishing a theoretical analytical method for female farmers to predict the value of their farmland.

The feminization of agriculture refers to the situation in which the size of the female agricultural labour force exceeds the size of the male agricultural labour force. We expect that, for individual farmers, the reported value of their farmland is based on either the information that the individual had during the survey interview or the family’s location. Individuals reported a current estimate of the monetary value required for them to make a one-time resale of farmland to others under realistic constraints. We define an individual’s psychological judgement of the value of his or her farmland as the monetization of the individual’s understanding of his or her farmland rights and interests, and the key to the gender difference between men and women in their expectations for the value of their farmland is the degree of the informational symmetry about farmland between males and females.

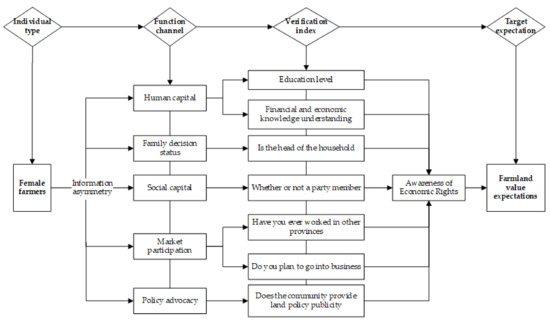

On the whole, the differences in the informational symmetry between individuals are mainly driven by five factors: (1) Human capital level. According to the basic principles of human capital theory, the level of human capital represents, to a certain extent, the individual’s ability to collect and process information and can reflect an increase in the awareness of his or her individual rights and interests, which is reflected in the accuracy of his or her estimates of resource prices in market transactions; (2) Family decision-making power. When individuals are the main decision-makers in their family, especially for important economic decisions, they seek to obtain more and more comprehensive market information as they make decisions, thereby enhancing their awareness of their economic rights. Whether women have a decision-making position in the family determines their role in agricultural production and directly affects agricultural land use behaviour, leading to gender differences in land value evaluation; (3) Social capital or political participation. In human society, participating in political activities can promote individuals’ understanding of social information and enhance their awareness of personal rights. Therefore, differences in political participation are also expected to affect the informational symmetry between males and females and the differences in their awareness of their rights; (4) Market participation. In a market-oriented era in which transactions and cooperation between individuals are emphasized, market participation not only grants individuals full access to market information but also help raise their awareness of their individual economic rights. For this reason, the differences in market participation also affect the informational symmetry between males and females regarding the value of farmland; (5) Policy publicity. Sufficient knowledge about economic policy enhances the individual’s awareness of their resource rights, and the extent of this policy awareness affects awareness of individual rights. For this reason, differences in policy perceptions or the attention given to a policy also affect the informational symmetry between males and females regarding their rights and interests related to their farmland. Given these factors, we propose a theoretical analytical framework for female farmers to make decisions about the value of farmland, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Theoretical analysis framework and verification ideas.

2.2. Research Hypothesis

Figure 2 shows the channels of action that may affect female farmers’ expectations of the value of their farmland and the typical indicators for the verification of those channels. If female farmers’ expected farmland value is higher than that of male farmers, then female farmers may display better outcomes than male farmers on five key dimensions: human capital, family decision-making power, social capital, market participation, and policy acceptance. If there is no obvious difference between female farmers and male farmers in the expected value of farmland, there are no obvious differences between the two in terms of human capital, family decision-making power, social capital, market participation, and policy acceptance. However, in terms of the current situation in rural China, female farmers are generally characterized by poorer outcomes on such indicators. Therefore, this study contends that female farmers’ expectations for the value of their farmland are lower than those of males, implying that female farmers’ awareness of their economic rights and interests regarding their farmland is also lower than that of male farmers. This would occur if, for females, their overall levels of human capital, family decision-making power, market participation, political participation, and policy awareness are inferior to those of males. Based on this logic, Hypothesis 1 is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Holding all else constant, female farmers have lower expectations than male farmers regarding the value of their farmland due to their disadvantages in terms of individual human capital, family decision-making power, market participation, political participation, and policy awareness.

In addition, according to expected value theory and planned behaviour theory, individual decision-making (both psychological and actual decision-making) are restricted by subjective internal and objective external factors. Therefore, in addition to exploring the influence of gender, variables relating to six characteristics of the interviewee, i.e., individual, family, property rights system, organization, location, and factor endowment variables, are controlled for. Regional characteristics are mainly controlled for with urban dummy variables, while land endowments are controlled for with dummy variables for the levels of land quality to eliminate bias in the estimated results due to differences in land quality.

3. Data, Variables, and Method

3.1. Data

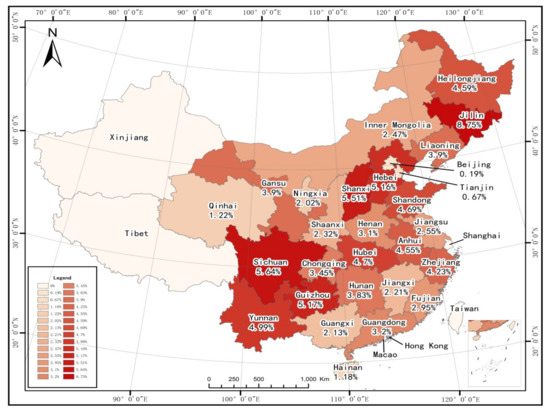

The empirical data come from the public database of the Chinese Household Finance Survey (CHFS), organized and implemented by the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics in Sichuan Province, China. To date, four waves of this stratified random sampling survey have been completed at the national level: 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2017. The database includes information at the individual, family, and regional levels. Due to a lack of data on the core variables in other years, in this paper, only the cross-sectional survey data for rural residents from 2015 is selected. The 2015 survey covered 29 provinces (including autonomous regions and municipalities, but excluding Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan), 351 counties (including districts and county-level cities), 1396 village (residential) committees, and 37,289 sample households. After deleting observations with a severe lack of data on urban residence and other core variables, 5245 observations were finally retained (28.67% from the east, 37.98% from the central region, and 33.35% from the west), accounting for 14.07% of the total sample. The sample distribution is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Sample distribution.

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. The Explained Variable

To ensure that the measure for the expected value of farmland is standardized and comparable, this paper selects the total area of farmland owned as the measure of farmland. The main reason is that farmland is the most important source of livelihood for small farmers in China, whose agricultural resources are relatively scarce. The farmer’s understanding of the economic value of his or her farmland represents well the overall attitude of farmers toward their farmland and their perceptions of their land rights and interests. Therefore, the dependent variable is the total area of cultivated land (excluding leased or borrowed cultivated land and referring to the land mainly used for the production of grain, oil, fruit and vegetables, excluding gardens, grassland and forestland). Additionally, the original questionnaire asked about the respondents’ expectations for the total monetary value of the cultivated land owned by the family based on current market prices. To ensure comparability between the dependent variables, the value of the farmland was measured per unit of area. Moreover, to overcome the collinearity and dimensionality problems, the explained variables were logarithmically transformed for use in the empirical model [49].

3.2.2. The Core Explanatory Variables

The core explanatory variable is the gender of the respondent, and gender is defined as a dummy variable, with females being assigned a value of 1 and males a value of 0.

3.2.3. The Control Variables

The control variables were chosen through reference to expected value theory and planned behaviour theory [46,47] as well as through an analysis of the factors affecting the willingness to transfer or withdraw from farmland and actually doing so [50,51,52] and of the factors that influence individual value perceptions [53,54]. Additionally, the property rights system and land quality are also key factors that affect land value. Therefore, in the consideration of the data available, in this article, characteristics related to six factors that affect farmers’ expectations for the value of their farmland were controlled for. These include the following: (1) other individual characteristics of the interviewee, including age, education level, and willingness to engage in business; (2) the family’s property rights over the farmland, including whether the family farmland is certified or not; (3) family characteristics, including annual per capita income, social security coverage, the degree of dependence on the farmland (separated into food dependence and income dependence), social capital, health status, land area per capita, household debt level, and experience with land acquisition (land acquisition changes the family’s land endowment); (4) the quality of cultivated land, measured with dummy variables; (5) community characteristics, including whether the community provides services to publicise relevant policies; (6) characteristics of the farmers’ operations. In addition, dummy variables for each city are also included. The definitions of and calculation methods for specific variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable meanings and assignment rules.

3.3. Methods

Given the linear functional relationship between the explained variable and the explanatory variable, we used a multivariate linear regression model, estimated with OLS, to estimate the gender difference in expectations for the value of farmland and the impact of other factors on those expectations using the principles of moderating effects models: we estimate the mechanism by which gender affects farmers’ expectations for their farmland’s value. The benchmark regression model is shown in Formula (1):

In Formula (1), Yi represents the i-th interviewed farmer’s expectation for the value of his or her farmland, α represents the intercept term, β represents the marginal effect of the core explanatory variable, gender, on the expected value of the farmland, and δ represents the marginal effects of other control variables on the farmers’ expectations. These other variables represent other unobservable random disturbances. Controli includes five types of variables: the individual characteristics of the interviewee, the characteristics of the property rights system, the characteristics of the family, the characteristics of the community, and the characteristics of the farmer’s operations. In addition, the dummy variables for farmland quality and each city are included to control for deviations in the estimation caused by differences across these two factors. In this article, the focus is on the values of α, β, and δ.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics of the main variables. The results show that, on average, farmers expect the value of their farmland to be 23,650.20 USD/km2, with a minimum of 229.20 USD/km2, and a maximum of 91,709.40 USD/km2 (in 2014 prices). By introducing interest rates and inflation, equivalent values in 2020 prices are calculated, giving an average current expected value of 31,454.85 USD/km2. According to the provincial-level statistics, the province in which farmers have the highest expectations for farmland value is Fujian Province in the southeast, with an average of 53,450.4405 USD/km2, and the province with the lowest expectations is Heilongjiang Province in the northeast, with an average of only 3715.2015 USD/km2 (in 2014 prices). In addition, the sampled farmers’ average perception of their social security is 2.215, but their trust in the government’s care for the elderly is 4.35. These results show that expectations for the value of farmland in China clearly differ across regions, with an overall decline in expectations from east to west, and rural residents’ have relatively poor perceptions of social security. The statistics for the other variables are shown below in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of main variables.

Table 3 reports the differences in the mean values of the individual and family characteristics between male farmers and female farmers. The results show that female farmers’ expectations for the value of their farmland was 2758.53 USD/km2 (in 2014 prices) lower than those of male farmers. Female farmers are also, on average, 3.728 years younger than male farmers, and have completed 0.425 fewer grades of education. They are also less willing to engage in business, have less personal social capital, are less likely to be party members, and have fewer local blood relatives. The number of female farmers and their experience of working in other provinces is also lower than those of male farmers, but female farmers are stronger than male farmers in terms of financial and economic knowledge and their perceptions of social security. This result shows that female farmers have less human and social capital than male farmers. In terms of family characteristics, female respondents’ households are 0.045 and 0.055 percentage points less dependent on their farmland for their food and income, respectively, than male respondents’ households. Their family’s social capital level is also lower by 0.018 points, but their debt is 1.475 points higher. However, there are no significant differences in social security coverage, per capita arable land area, per capita income, or experience with land acquisition. The specific mean t test results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Grouped mean t-test.

4.2. Empirical Results and Explanations

4.2.1. Basic Linear Regression Results

This paper calculates variance inflation factors (VIF) and a correlation coefficient matrix to estimate the extent of collinearity between variables. The results show that there are no serious collinearity problems among the variables (see Table A2). Table 4 reports the empirical results from the basic linear model: the goodness of fit, or R2, is 0.297 (p value = 0.000), and the robustness of the results is ensured by the gradual addition of variables. From Table 4, Columns (6) and (7), the results consistently show that the explanatory power of the model is robust. The R2 value indicates that the variables included in the model can explain 29.7% of the variation in the expectations of farmland value.

Table 4.

Basic linear regression results.

Regarding the influence of gender, in Table 4, from Columns (1) to (7), control variables such as farmland certification status, family characteristics, other individual characteristics of the respondent, community characteristics, and family organizational and operational characteristics, are gradually added to estimate the robustness of the results. The coefficient on gender of −0.21 means that, between males and females, there is a 21% difference in expectations for the value of farmland. Because females are assigned a value of 1 and males a value of 0, females’ expectations for the value of their farmland are approximately 21% lower than those of males. The marginal effects in Columns (6) to (7) show completely consistent results, which shows that the estimation results in this article are robust. Therefore, there are clear gender differences in expectations for the value of farmland, and that those of female farmers are much lower than those of male farmers.

Regarding the influence of the other variables, the certification and confirmation of farmland rights, household per capita income, previous experience with land acquisition, education level, and willingness to engage in business all have a significantly positive impact on the expectations for the value of farmland. Farmers with more land acquisition experience, higher education levels, and a greater willingness to engage in business have higher expectations for the value of their farmland. Having clear property rights represents an exclusive right to work the owned farmland, while having a right to resources often represents having additional benefits. Education represents human capital and negotiation ability. The stronger one’s ability to negotiate, think about resources, and process information is, the greater that individual will judge the value of a certain resource to be. Being willing to engage in business may arise from a desire to accumulate primitive capital through land. For example, some studies have found that profit-making opportunities significantly increase the rent of farmland [55]. The coefficient on land acquisition experience is 0.371, which means that agricultural families that have previously sold land have expectations for the value of their farmland that are 37.1% higher than those of agricultural families that have not previously sold land, and this effect is extremely obvious. There are empirical explanations for this phenomenon: because land acquisition changes the family’s land endowment (land becomes scarcer) and because of the effect of scarcity, farmers have higher expectations for the value of their remaining land [49].

In addition, the extent to which farmers are dependent on their farmland for income, their age, and the per capita area of farmland owned by agricultural households all have negative and significant effects on expectations for farmland value. Farmers who are less dependent on their land for income and who have less per capita arable land area have higher expectations for the value of their farmland, while older households have lower expectations. One possible explanation for the higher expectations of farmers who are less dependent on their farmland is that such households have nonagricultural income and nonagricultural employment. For families that are highly dependent on their farm for income, as they obtain more business information through their nonagricultural employment and become more likely to transfer into nonagricultural activities, farmland may be used as a source of primitive capital accumulation. This series of factors leads to an increased dependence on farmland for income. Families with lower levels of income dependence have higher expectations for the value of their farmland; that is, farmland is likely to become an important source of capital accumulation as farmers begin to carry out nonagricultural activities. Of course, the results for the region and cultivated land-quality dummy variables show that better-quality cultivated land and farmers with higher value expectations are located in the eastern, more developed areas. Factors such as household debt, social security, dependence on agricultural land for food, social capital, community, and organizational characteristics have no significant impact on the value of agricultural land. The specific empirical results are shown in Table 4.

4.2.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

To further understand the heterogeneity in the expectations for the value of farmland among female farmers, we focus on individual educational attainment, financial and economic knowledge, willingness to engage in business, perceptions of social security, party membership, head-of-household status, work experience in other provinces, the number of elderly family members, and the economic region in which they are located. China is divided into three regions: the eastern, central, and western regions (overall economic development levels decrease from east to west). Our regional variable equals 1 for the east, 2 for the central region, and 3 for the west, and the observations in our sample are distributed as follows: 518 in the east (accounting for 27.94% of the total sample), 756 in the central regions (accounting for 40.78%), and 580 in the west (accounting for 31.28%). To estimate the heterogeneity among female farmers, nine variables that capture that heterogeneity are added as additional control variables and the regression is estimated for the female sample only. The specific estimation model is shown in Formula (2).

Table 5 reports the empirical results of heterogeneity analysis. The empirical results show that there are no significant differences among female farmers in terms of their financial and economic knowledge, willingness to engage in business, perceptions of social security, party membership, head-of-household status, work experience in other provinces, or the number of elderly family members. There are obvious differences in educational attainment and region. These results show that female farmers with higher education levels and those located in the economically developed eastern region have higher expectations for the value of their farmland, which means that the regional economic development level and individual educational attainment have a positive effect on the improvement in women’s understanding of their economic rights and interests. According to the data, the average education level of female farmers in the western region is 2.344 years of schooling, while the average education level of female farmers in the central and eastern regions is above 2.5, which is significantly higher than that in the western region. This empirical structure is important.

Table 5.

Heterogeneity analysis: individual characteristics, family characteristics and regional characteristics.

4.2.3. Analysis of the Underlying Mechanisms

What are the key factors that cause female farmers to underestimate the economic value of their farmland relative to male farmers? The theoretical analysis section pointed out the channels that affect female farmers’ expectations for the value of their farmland. There are four main channels, namely, human capital, social capital, economic decision-making power, and policy awareness or propaganda. To verify these channels, we represented human capital mainly through three variables: education level, financial and economic knowledge level, and work experience in other provinces. Social capital is mainly represented by party membership (political participation), and economic decision-making power is measured as head-of-household status. As represented by willingness to engage in business, the degree to which attention or publicity is given to land-related policy is represented by the farmers’ judgements of whether their community provides policy services (Yes = 1; No = 0). The cross-term in a “regulatory effects” model can well identify any moderating effects between two variables; that is, the interaction effect is the moderating effect [56,57]. For this reason, in this article, the principles behind the moderating effects model are used to estimate the channels that lead to female farmers’ expectations for the value of their farmland being lower than those of male farmers. The estimation model is shown in Formula (3).

Since female farmers are assigned a value of 1 and male farmers are assigned a value of 0, and in view of the correlations among the variables, we made the following inferences: (1) If female farmers are less aware of their economic rights than male farmers due to their inferior human capital, then the estimated coefficients on “gender * education level”, “gender * financial and economic knowledge”, and “gender * work experience in other provinces” will be significantly negative. (2) If female farmers have a lower level of social capital and if their perceptions of their economic rights are lower than those of male farmers, then the estimated coefficient on “gender * party member status” will be significantly negative. (3) If female farmers have less economic decision-making power, which leads to their lower awareness of their rights and interests, then the estimated coefficients on “gender * head-of-household status” and “gender * willingness to engage in business” will be significantly negative. (4) If female farmers pay less attention to the community-based publicity of land policies, which leads them to have lower expectations for the value of their farmland than male farmers, then the estimated coefficient on “gender * community provides policy services” will be significantly negative.

During the estimation of the regression, there were many missing values for party membership and work experience in other provinces. To protect the authenticity of the data, these missing values were not filled in. A total of 2115 observations were included in the regression (40.32% of the total sample). Table 6, Columns (1)–(7), report the results for the verification of the four channels of human capital, social capital, economic decision-making power, and policy attention. The results show that only two channels, whether the community publicises land-related policy and has a willingness to engage in business, are significant, and the coefficient on “gender * whether the community provides policy services” is significantly negative. Female farmers pay less attention to farmland-related policies or else lack local policy publicity. However, the coefficient on the interaction between the willingness to do business and gender is significantly positive, which shows that female farmers are much more willing to engage in business than male farmers when their expectations for the value of their farmland is lower than that of male farmers. This result is not in line with previous inferences, and, in the mean t test, male farmers’ willingness to engage in business is much higher than that of female farmers. According to previous researchers, “female farmers are significantly less willing to work in agriculture than male farmers, and their willingness to transfer land is significantly higher than that of male farmers; that is, they are more inclined to transfer farmland” [58]. The explanation we give in this article is that, because female farmers are physically unsuitable for the high-intensity labour required for agricultural production and management activities, they may be more willing to engage in business (referring to nonagricultural industries and commerce). Farmland is an important way for farmers to accumulate capital for participation in other commercial activities. It may be that female farmers are more eager to engage in business and urgently need to transfer land to make basic adjustments in their nonagricultural employment, leading to relatively low estimates of the value of their farmland value. The effects of household-head status, human capital, social capital, and economic decision-making power have not been tested for significance. These results also show that the gaps between rural Chinese females and males in terms of human capital, labour mobility, political participation, and family economic decision-making power are gradually narrowing, but the gap in the reception of policy information is still somewhat large. In addition, female farmers have shown less willingness to learn about these policies because of their urgent need to transition from agriculture to other work, but this reality hinders females from becoming aware of their economic rights and interests.

Table 6.

Mechanism analysis.

5. Discussion, Conclusions and Enlightenment

5.1. Discussion

Based on data for 5245 rural households in China, this study focuses on the analysis of gender differences in expectations of farmland value and the main factors leading to such differences. With respect to the important trend of the feminization of agriculture, research focuses mainly on the basic concepts of feminization, its causes, and its impacts on three main aspects, namely, women’s rights, family decision-making, and agricultural production and management [59]; however, gender differences in the value expectations of agricultural land in this context remain largely unexplored, and our research thus focuses on these differences and their drivers. In addition, although some researchers have found through empirical research that female farmers have lower expectations for the value of farmland than male farmers, they have not analysed and verified the mechanism and reasons for this difference [49]. Therefore, this study further expands the investigation on the scope of the influence of agricultural feminization, especially the influence on the perception of women’s rights. In addition, it identifies the driving factors of female farmers’ expectations of lower farmland value [60]. Our empirical results show that, because female farmers have lower policy acceptance than male farmers and a stronger willingness to engage in business, their expectations of the value of farmland are lower than those of men.

Some researchers have pointed out through observation and analysis that the rights and interests of female farmers in land transfer have not been substantively guaranteed [59] and that the feminization of agriculture does not drive improvement in the broader indicators of women’s social or economic empowerment [11]. The current study finds that female farmers’ lower policy acceptance and stronger willingness to engage in business leads them to expect lower farmland valuations than men. This finding provides evidence to support the above conclusions.

Some researchers believe that the social security value of agricultural land has an important impact on the market value of agricultural land, especially the price negotiated by farmers in the land acquisition market [44]. Some researchers have also argued that, when the level of dependence on agricultural land is low, farmers lower their expectations of the value of farmland and are more inclined to withdraw from farmland management [51]. However, this study shows that, while the level of social security is positively correlated with the valuation, the impact is not significant, and the level of agricultural land income dependence is obviously negatively correlated. This shows that, when the impacts of the social security level and the degree of dependence on farmland are not strictly linear and the proportion of nonagricultural income in farm households is increasing, the farm households’ expectations of the value of farmland change.

This study has several limitations, which can be addressed in future studies. These limitations are as follows: (1) This study analyses gender differences in the expected value of farmland across farmer households but does not analyse differences between male farmers and female farmers within the same family and their influencing factors within the family. The results may be affected by other farmland characteristics, such as crop varieties and utilization types. (2) This study analyses gender differences in the value of farmland only in the cross-section but does not effectively identify the impact of dynamic changes in other factors on these differences. Future research can identify the impact of dynamic changes in the influencing factors over time. (3) This study analyses gender differences in the expected value of agricultural land in the specific context of public ownership of agricultural land in China. In the future, we can further analyse such differences in countries with private land ownership and their influencing factors. (4) This study analyses, gender differences are in the expected value of agricultural land only and does not take into account other land types, such as homesteads, gardens, and grasslands. In the future, we can further analyse gender differences in value expectations for other land types. (5) This study analyses gender differences in the value of farmland against the background of agricultural feminization and the reasons for this difference. It does not analyse the driving factors of the feminization of agriculture, especially the factors that affect the role of women in agriculture. In the future, we will further use observational data at the farmer household level to explore the driving factors behind women’s changing roles in agricultural operations.

5.2. Conclusions

The main conclusions of this article are as follows:

- (a)

- In the context of the feminization of agriculture, female farmers less attentive to policy and have a more urgent need to transfer to nonagricultural work, leading them to have significantly lower expectations for the value of their farmland than male farmers;

- (b)

- Among female farmers, those who are located in areas with higher levels of economic and social development and who have a higher level of educational attainment have higher expectations for the value of their farmland;

- (c)

- The confirmation and certification of farmland rights, per capita household income levels, experience with land sales, educational attainment, and willingness to engage in business all have significant positive effects on expectations for agricultural land values. Farmers with more experience with land sales, higher educational attainment, and a greater willingness to engage in business have higher expectations for the value of their farmland;

- (d)

- The extent to which farmers are dependent on their farmland for income, their age, and the per capita area of farmland owned by their household (the scarcity of farmland) have significantly negative impacts on their expectations for the value of their farmland. Farmers who are more dependent on their farmland for income and who have less farmland per capita have higher expectations for the value of their farmland, while older households have lower expectations. For rural households, farmland may act as a “warehouse” for family wealth accumulation; that is, it may become a way to allocate diversified assets [61] or the source of capital for a transition to nonagricultural work. This shows that farmland is no longer limited to supplying welfare to rural household or securing their livelihoods [62,63,64].

5.3. Enlightenment

The above conclusions show that effectively publicising policies promotes an increasing awareness of women’s rights and interests, and that economic and social development and improvements in women’s educational attainment also help to enhance the awareness of women’s rights and interests. Based on the above findings, we can also derive some policy implications. For policymakers, it is important, on the one hand, to be timely in understanding the changes in land functions across different social scenarios and to formulate targeted land transfer and management policies to improve the efficiency of farmland utilization, and, on the other hand, to gradually eliminate regional economic and educational gaps, and to improve policies related to farmland and other similar topics. Especially for the purpose of understanding how women receive information, the methods and forms by which China’s farmland policies are publicised should be improved and, through the adjustment of the industrial structure, suitable employment opportunities for women that fully incorporate women’s comparative advantages should be created, which will improve the quality of urbanization and eliminate the negative effects of gender differences and regional imbalances in the economy and society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: Z.Y., F.W. and Y.Q.; methodology: Z.Y., F.W., X.D., C.L. and Y.Q.; software: Q.H.; validation: F.W., Q.H. and X.D.; Funding acquisition: Y.Q.; formal analysis: C.L.; investigation: Y.Q.; resources: Z.Y.; data curation: Z.Y., X.D. and C.L.; writing—original draft preparation: Z.Y., F.W.; writing—review and editing: Y.Q., F.W. and Z.Y.; visualisation: Z.Y., X.D. and C.L.; supervision: Z.Y., F.W and Y.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China (grant number: 14XGL003) and Sichuan Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Office (grant number: SC21C047).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The current investigation uses data from the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS2015) by the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics. (https://chfs.swufe.edu.cn/, accessed on 20 March 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Notes and information reference source.

Table A1.

Notes and information reference source.

| Numbering | Notes and Reference Source |

|---|---|

| 1.1 | 2017 Migrant Workers Monitoring Report [EB/OL].18-o4-27] http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/201804/t20180427_1596389.html, accessed on 25 February 2021 |

| 1.2 | Data Sources::http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjgb/nypcgb/, accessed on 16 March 2021 |

Table A2.

Matrix of correlations.

Table A2.

Matrix of correlations.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Logarithm of the expected value of farmland value | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||

| (2) Gender | 0.061 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||

| (3) Whether to confirm the right to issue a certificate | 0.006 | 0.046 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| (4) Family social security coverage rate | 0.054 | 0.018 | 0.010 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| (5) Degree of food dependence on farmland | −0.046 | 0.034 | 0.063 | 0.003 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| (6) Farmland income dependence | −0.089 | 0.074 | 0.003 | 0.022 | 0.082 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (7) Farmland area per household | −0.126 | 0.008 | −0.026 | −0.012 | −0.007 | 0.087 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (8) Does the family have public officials | 0.032 | 0.042 | −0.008 | 0.063 | 0.041 | 0.042 | 0.007 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (9) Annual income per capita of the family | 0.047 | 0.011 | 0.001 | −0.019 | −0.041 | 0.135 | 0.123 | 0.023 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (10) Household debt level | −0.026 | −0.019 | −0.018 | −0.041 | −0.010 | 0.098 | 0.015 | 0.010 | −0.032 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (11) Whether there is a dummy variable of land acquisition experience since 2000 | 0.113 | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.012 | −0.025 | −0.011 | −0.022 | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.027 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (12) Age | −0.079 | 0.146 | 0.032 | 0.051 | 0.044 | −0.101 | −0.026 | −0.007 | −0.092 | −0.093 | −0.016 | 0.146 | 1.000 | ||||

| (13) Education | 0.110 | 0.197 | 0.018 | 0.066 | −0.069 | 0.083 | 0.049 | 0.096 | 0.131 | −0.010 | 0.048 | 0.197 | −0.301 | 1.000 | |||

| (15) Willingness to do business | 0.037 | 0.035 | 0.000 | −0.021 | −0.018 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.044 | 0.040 | 0.042 | 0.056 | 0.035 | −0.209 | 0.067 | 1.000 | ||

| (16) Whether the community provides policy services | 0.045 | 0.057 | 0.024 | 0.043 | 0.024 | −0.012 | −0.020 | 0.071 | 0.001 | −0.006 | 0.010 | 0.057 | 0.028 | 0.040 | −0.007 | 1.000 | |

| (17) Organizational level | −0.032 | −0.035 | 0.018 | 0.019 | 0.004 | −0.068 | −0.023 | −0.067 | −0.054 | −0.079 | 0.001 | −0.035 | 0.042 | −0.036 | −0.011 | −0.046 | 1.000 |

References

- Chant, S. Re-thinking the “feminization of poverty” in relation to aggregate gender indices. J. Hum. Dev. 2006, 7, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieri, S. New ruralities—old gender dynamics? A reflection on high-value crop agriculture in the light of the feminisation debates. Geogr. Helv. 2014, 69, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaddis, I.; Klasen, S. Economic development, structural change, and women’s labor force participation: A reexamination of the feminization U hypothesis. J. Popul. Econ.-Ics 2014, 27, 639–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.X. Contemporary China’s rural labor transfer and agricultural feminization trend. Sociol. Res. 1994, 2, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S. Gender differences in rural labor mobility. Sociol. Res. 1997, 1, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthy, P. Why are men doing floral sex work? Gender, cultural reproduction and the feminization of agriculture. Signs 2010, 35, 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartaula, H.N.; Niehof, A.; Visser, L.E. Feminisation of agriculture as an effect of male out-migration: Unexpected outcomes from Jhapa District. East. Nepal. Int. J. Interdiscip. Soc. Sci. 2010, 5, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oseni, G.; Corral, P.; Goldstein, M.; Winters, P. Explaining gender differentials in agricultural production in Nigeria. Agric. Econ. 2015, 46, 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SLavchevska, V. Gender differences in agricultural productivity: The case of Tanzania. Agric. Econ. 2015, 46, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Huang, L. What is “Agricultural Feminization”: Discussion and Reflection. J. Agric. For. Econ. Manag. 2017, 16, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, I.; Lahiridutt, K.; Lockie, S.; Pritchard, B. The feminization of agriculture or the feminization of agrarian distress? Tracking the trajectory of women in agriculture in India. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2018, 23, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terri, R.; Anríquez, G.; Croppenstedt, A.; Gerosa, S.; Lowder, S.K.; Matuschke, I.; Skoet, J. The Role of Women in Agriculture; ESA: Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 3, p. 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyalo, P.O. Women and agriculture in rural Kenya: Role in agricultural production. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2019, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Levelling the Field: Improving Opportunities for Women Farmers in Africa; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ngomane, T.S.; Sebola, M.P. Women in Agricultural Co-Operatives for Poverty Alleviation in Mpumalanga Province: Challenges, Strategies and Opportunities. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives, Johannesburg, South Africa, 3–5 July 2019; Available online: http://ulspace.ul.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10386/2713/ngomane_women_2019.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2010–2011: Women in Agriculture—Closing the Gender Gap for Development; United Nations: New York, UK, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inhetveen, H.; Schmitt, M. Feminization Trends in Agriculture: Theoretical Remarks and Empirical Findings from Germany; Women in the European Countryside; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Eapen, L.M.; Nair, S.R. Rarian performance and food price inflation in India. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2015, 50, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.F.; Liu, J. Is agricultural land “feminized” or “aging”? Popul. Res. 2009, 2, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, T.; Chandrasekhar, S.; Gandhi, I. Short-term migrants in India: Characteristics, Wages and Work transition. Work Pap. no. 2015. Available online: http://oii.igidr.ac.in:8080/xmlui/handle/2275/355 (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Wei, J.Q.A. Study on the Feminization of Agriculture from the Perspective of Population Security. Northwestern Popul. 2016, 37, 03:84–88, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.F.; Guo, P.A. Summary of the Research on Left-behind Women in Rural my country in the Past Ten Years. J. Inn. Mong. Agric. Univ. 2020, 22, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, I.; Lahiri-Dutt, K. What determines women’s agricultural participation? A comparative study of landholding households in rural India. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 76, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.Q.; Wang, X.Q.; Lu, W.Y.; Liu, Y.Z. The characteristics of agricultural labor force, land fragmentation and agricultural machinery socialization service. Res. Agric. Mod. 2016, 37, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.Y.; Wen, L. Does the aging and feminization of rural labor force reduce the efficiency of food production? A comparative analysis of North and South based on stochastic frontiers. Agric. Technol. Econ. 2016, 2, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Qi, C.J.; Hu, X.Y. The impact of aging, part-time employment, and feminization on the input of household production factors: An empirical analysis based on data from fixed observation points in rural areas across the country. Stat. Inf. Forum 2018, 33, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Wang, J.M. Analysis of the impact of aging and feminization of farmers on the production efficiency of planting industry: Based on 824 survey samples in Heilongjiang Province. Agric. Econ. 2019, 3, 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhao, L.G. The “feminization” of agricultural labor force and its impact on agricultural production—Based on the empirical analysis of Liaoning Province. China Rural. Econ. 2009, 5, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, S.C. Gender division of labor and feminization of agriculture: An empirical analysis based on 408 sample families in Jiangsu. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2010, 10, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.W. Research on the imbalance of China’s urban and rural labor market. Ph.D. Thesis, Shandong Agricultural University, Taian, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Chen, S.; Huang, L. A Study on the Life Satisfaction of Farming Women under “Male Workers and Women Farming”—Based on the Analysis of 1367 Female Samples in Anhui Province. J. Agric. For. Econ. Manag. 2018, 18, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brauw, A.; Rozelle, S. The Consistency of Return to Education for Non-agricultural Employment in Rural China. China Labor Econ. 2009, 5, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Quisumbing, A.R. Male-female Differences in Agricultural Productivity: Methodological Issues and Empirical Evidence. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1579–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Brauw, A.D.; Rozelle, S. China’s rural labor market development and its gender implications. China Econ. Rev. 2004, 15, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauw, A.D.; Qiang, L.; Liu, C.; Rozelle, S.; Zhang, L. Feminization of agriculture in China? Myths surrounding women’s participation infarming. China, Q. 2008, 194, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauw, A.D. The feminisation of agriculture with Chinese characteristics. J. Dev. Stud. 2013, 49, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Eriksson, T.; Zhang, L.; Bai, Y. Off-farm employment and time allocation in on-farm work in rural China from gender perspective. China Econ. Rev. 2016, 41, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, D.Y.; Wu, X. Research on China’s Agricultural Technical Efficiency and Total Factor Productivity—Based on the Perspective of Rural Labor Structure Changes. Economist 2013, 9, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.Y.; Wen, L. The change of rural labor structure and the technical efficiency of food production. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2015, 14, 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, A.P.; Dong, F. Analysis of Feminization of Agriculture, Feminization of Agriculture and the Impact on Poverty—Based on the Survey Data of Farmers in 14 Poor Villages in Gansu Province. Popul. Dev. 2018, 24, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.D. The Legislative Choice of Fair Compensation: Questioning the Market Price Standard of Agricultural Land Compensation. China Land Sci. 2013, 27, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. The dilemma of my country’s rural land expropriation and its solution—Based on the perspective of food security and choice value. Theor. Mon. 2013, 7, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H. Discussion on the Essence of Compensation Standards for Land Expropriation—Also on the Method of Measuring and Calculating Compensation Prices for Market-based Land Expropriation. Product. Res. 2014, 9, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.Y.; Huang, T.Z. Agricultural land market value evaluation model and its application in my country’s land acquisition compensation. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2014, 13, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Codosero Rodas, J.M.; Naranjo Gómez, J.M.; Alexandre Castanho, R.; Cabezas, J. Land Valuation Sustainable Model of Urban Planning Development: A Case Study in Badajoz, Spain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atkinson, J.W. Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavio. Psychol. Rev. 1957, 64, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichian, A.A. The Collective Works of Armen A, Michigan: Edwards Brothers. Inc. 1994. Available online: https://xs2.dailyheadlines.cc/scholar?q=The+Collective+Works+of+Armen+A%2C+Michigan%3A+Edwards+Brothers (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Yan, Z.C.; Wei, F.; Deng, X.; Chuan, L.; Qi, Y.B. Does Land Expropriation Experience Increase Farmers’ Farmland Value Expectations? Empirical Evidence from the People’s Republic of China. Land 2021, 10, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Jiang, T.; Guo, L.Y.; Gan, L. Development of China’s Agricultural Land Circulation Market and Research on Farmland Circulation Behavior of Farmers—Based on the Survey Data of Farmers in 29 Provinces from 2013 to 2015. Manag. World 2016, 6, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.W.; Gu, H.Y. Urban housing, agricultural land dependence and the withdrawal of rural households’ contract rights. Manag. World 2016, 9, 55–69, 187–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.G.; Zhan, P.; Zhu, J.F. Land circulation, factor allocation and improvement of agricultural production efficiency. China Land Sci. 2020, 34, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, X.Q.; Zhong, X.Y. Study on the influencing factors of psychological perception in the formation of conflict willingness of land-lost farmers. Resour. Sci. 2013, 35, 2418–2425. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, H.J.; Fang, Y.; Lei, P. Land expropriation conflict of interest: The behavioral selection mechanism of local government and land-lost farmers and its empirical evidence. China Land Sci. 2016, 30, 21–27, 37. [Google Scholar]

- AnderWeele, T.J. Mediation Analysis: A Practitioner’s Guide. Annu. Rev Public Health 2016, 37, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qiu, T.W.; Luo, B.L.; He, Q.Y. The Transformation of Agricultural Land Circulation Market: Theory and Evidence: Based on the Analysis of the Relationship between Agricultural Land Circulation Objects and Agricultural Land Rent. China Rural. Obs. 2019, 4, 128–144. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.L.; Hou, J.T.; Zhang, L. The Comparison and Application of Moderating Effect and Mediating Effect. Acta Psychol. 2005, 2, 268–274. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Jiao, F.F.; Huang, L. Comparison of Differences in Farming Willingness and Its Influencing Factors from the Perspective of Gender—Based on 2073 Samples of Anhui Province. J. Shanxi Agric. Univ. 2019, 18, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H. Research on the Feminization of Agriculture: Retrospect and Prospect. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. 2019, 21, 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, D. The issue of rural women’s land rights under the background of agricultural feminization: A gender legal analysis based on the concept of free development. Hebei Sci. Law 2014, 32, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.C. Economic Interpretation; CITIC Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2019; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, T.J. Reinterpretation of my country’s Rural System Change. China Natl. Cond. Power 2000, 4, 35–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.L. System Reform under the Condition of Farmland Security and Withdrawal: Welfare Function Transferring Property Function. Reform 2013, 1, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.P.; Luo, B.L. Analysis of the internal mechanism and influencing factors of agricultural land adjustment. China Rural. Econ. 2015, 3, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).