2. Methods

Before starting the procedures, the team of specialists, including a fetal cardiologist (J.D.), a feto-maternal specialist (M.D.), and an interventional cardiologist (A.K.), was formed and the preliminary protocol was prepared. Having observed cardiac interventions in another center, the whole group took part in the procedures in the dissecting room on a cardiac specimen (

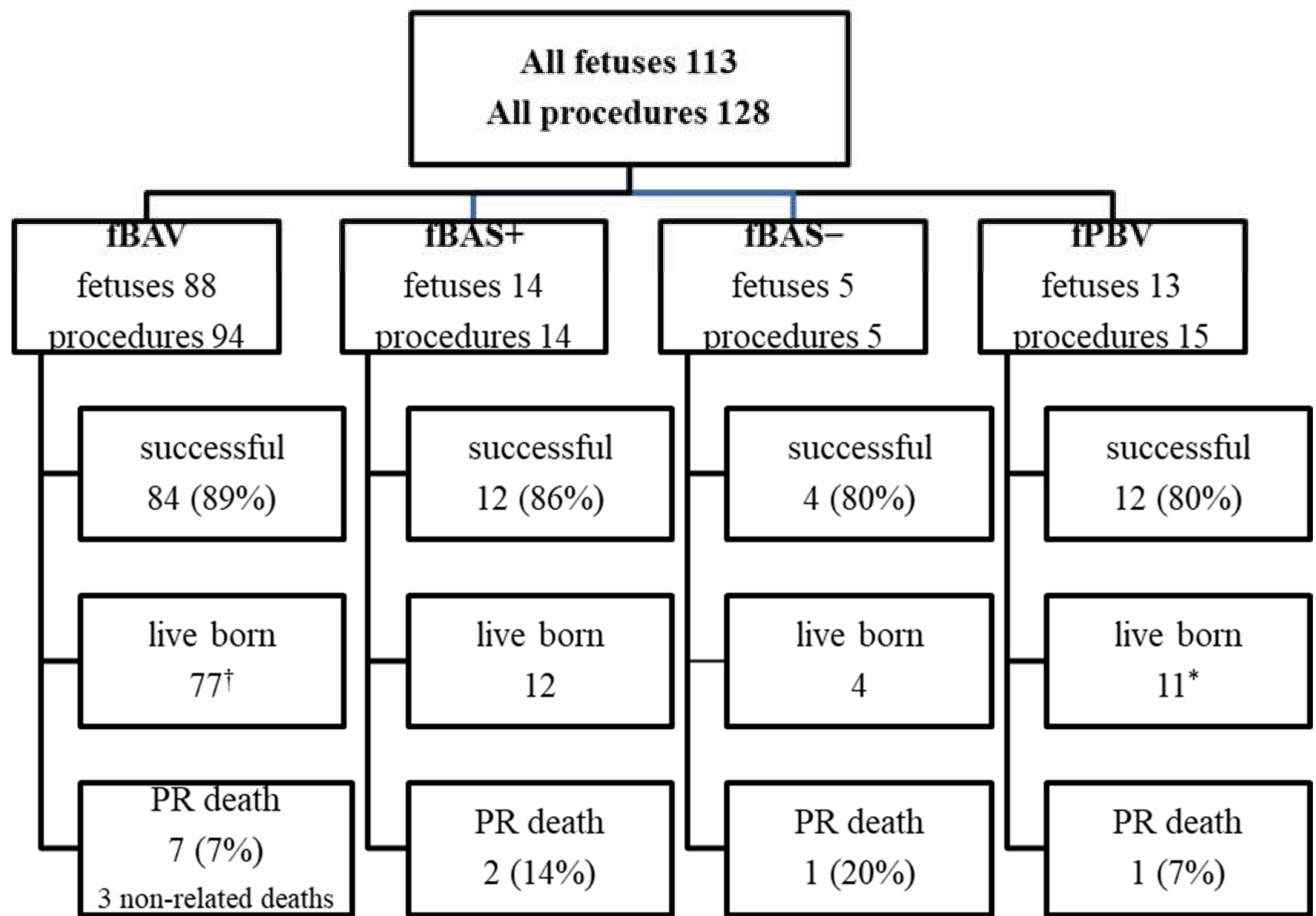

Figure 1). This training was undertaken to check the proportion between fetal heart structures and used equipment. The program was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Centre of Medical Postgraduate Education and offered for all patients at no cost as a part of national health insurance. Data of FCI were gathered prospectively since the beginning of the program. All fetuses underwent echocardiography with detailed structural and hemodynamic assessment in the Department of Perinatal Cardiology and Congenital Anomalies, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, US Clinic Agatowa, and the procedures were performed in the 2nd Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education in Bielanski Hospital, Warsaw. The computer database of the results of fetal echocardiography exams and records of all fetal interventions from June 2011 to March 2020 were reviewed. All fetuses who underwent FCI were included in this study (

Figure 2). We analyzed the maternal and fetal anesthesia and technical aspects of consecutive procedures, ways in which we dealt with arising complications that were crucial for the safety and success of the procedure, and issues that could lead to failure or complications of FCI (

Table 1).

Fetuses for FCI were recruited on the basis of the international criteria [

3,

4,

5]. Following a detailed fetal echocardiography, parents were initially counselled by the fetal cardiology specialist. After being admitted to the hospital, the mother was examined by an obstetrician and signed an informed consent form and agreement for the experimental therapy. There were no mothers’ contraindications to the procedure; one procedure was delayed for one week because the pregnant woman was treated with acetylsalicylic acid for obstetric reasons. In 6 cases we withdrew from the procedure (in 4 cases due to persistent unfavorable fetal position, in 2 cases mother resigned after giving initial consent).

All fetal interventions were performed by the same team: the fetal cardiologist (J.D.), the feto-maternal specialist (M.D.), the interventional cardiologist (A.K.). The ultrasound machine during the procedure was operated by another obstetrician (B.R.), who also took care of patients before and after the procedure. The operating theatre team consisted of an anesthesiologist, an anesthesiology nurse and a scrub nurse.

The protocol on preparing pregnant women for the fetal intervention was established.

The equipment for interventional procedures: needles, guidewires, balloon catheters and stents, were prepared based on their current availability in Poland. (

File S1)

All procedures were performed in an antiseptic environment of the operating theatre, percutaneously under ultrasound guidance. The surgical site was prepared by applying an antiseptic solution and then covering with surgical plastic drapes. Then the ultrasound probe was covered by a sterile protection sleeve and sterile ultrasound gel was applied. The mother was placed on her back, or slightly on her left or right side, depending on the fetal position. If the fetal position was unfavorable, the team tried to change it before the procedure asking the mother to do certain exercises. Sometimes external manual maneuvers were performed on the fetus. The procedure was started if the position of the fetus was optimal or close to optimal, and it was eventually possible to correct it by moving the fetus with the needle introduced into the uterus.

Basing on the data gathered from international publications [

6] we performed our first 8 procedures (7 aortic valvuloplasties and 1 balloon atrioseptoplasty) under general anesthesia of the mother while the fetus was indirectly anesthetized by medications (fentanyl and midazolam) crossing the placenta.Before each procedure cordocentesis was performed to take 4 mL fetal blood sample for NTproBNP, CRP, procalcitonin concentration and genetic tests to diagnose possible coexisting problems in the fetus. Beginning from the 9th procedure we replaced fetal transplacental anesthesia by giving fentanyl and atracurium directly into the umbilical vein. From the 32nd procedure atropine was added before the procedure aiming to decrease the risk of fetal bradycardia.

Before introducing the 18G needle the mother’s skin was additionally anesthetized with local lidocaine. The obstetrician performed the fetal blood sampling (FBS) and cardiac puncture with the left hand, keeping the ultrasound probe in the right hand to monitor the procedure. (

Figure 3) To achieve the perfect angle for insertion of the needle, the obstetrician if needed corrected slightly fetal position with the 18 G needle (after she withdrew the tip of the trocar to avoid injury of the fetus). In 3 cases two 18 G needles were used during one procedure - one was necessary to stabilize fetal position and the other to puncture fetal heart. In 3 cases interventions were cancelled after mother and fetal anesthesia because the fetuses changed in the meantime their positions significantly, thus safe and successful operation was not possible.

The equipment for cardiac interventions was prepared by the cardiologists. The optimal balloon size was chosen on the basis of the type of intervention and valve annulus diameter measured directly before the procedure. In the majority of cases, the fetal heart was punctured with a 18 G needle; a 17 G needle was used only when a 4.5 mm or 5 mm balloon or a stent larger than 4 mm was used. In such cases, using a Y-connector was necessary to avoid fetal blood loss through the space between the catheter and the needle. A coronary guidewire was introduced through the needle; it was cut before the intervention to obtain the appropriate length for manipulation. A torquer was put on it to improve guidewire handling.

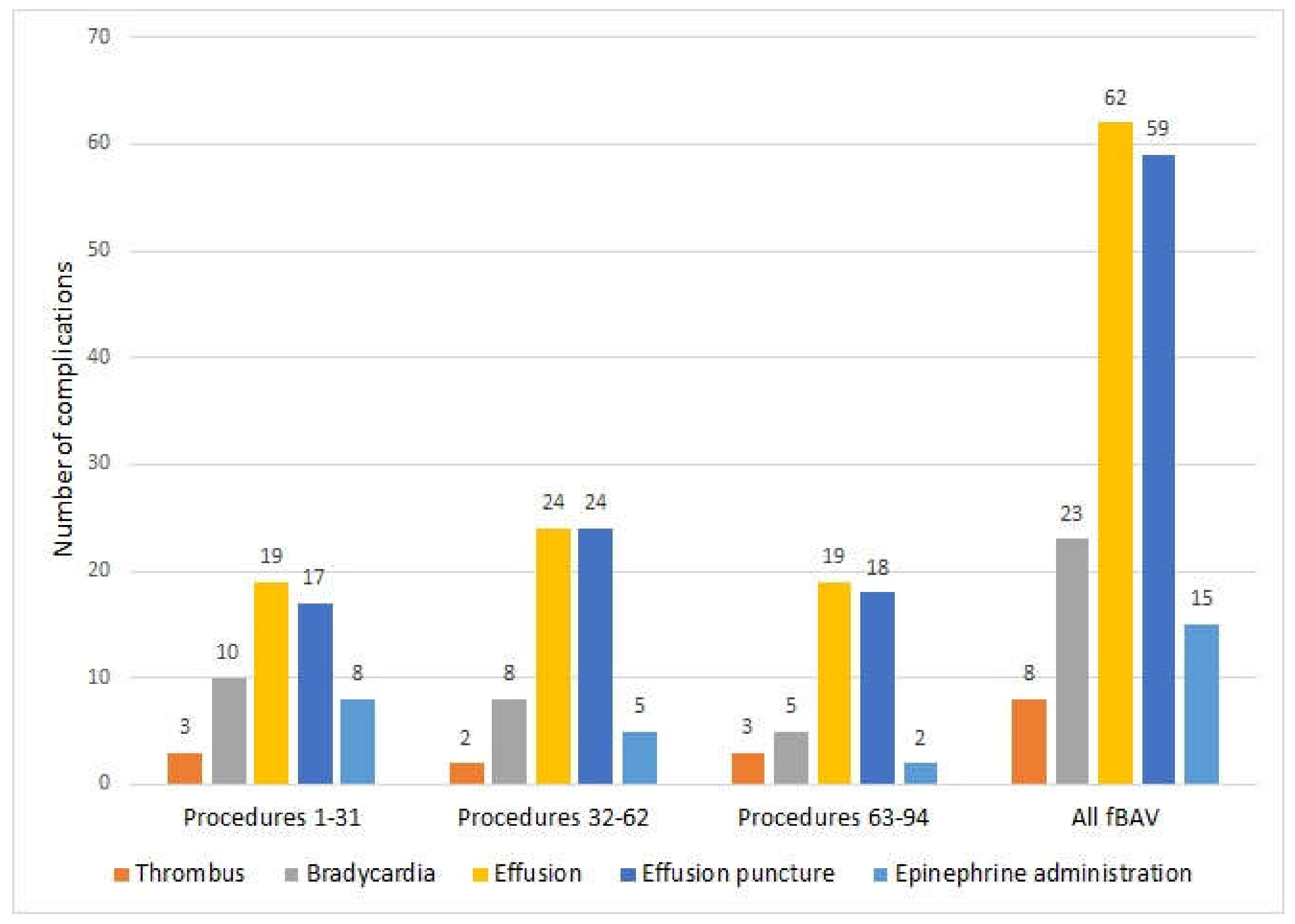

Guidewires and catheters were washed with 0.9% NaCl solution before insertion into the needle for a better slip. Beginning with the 32nd procedure, we started to add standard heparin (UFH) to this solution, aiming to decrease the risk of clotting formation during manipulation within the cardiac cavities. From the 36th procedure, we proceeded to rapidly evacuate even a small amount of pericardial effusion; since it was the most common cause of fetal bradycardia, we did not wait until bradycardia occurred.

After each procedure, the fetus was monitored with ultrasound for 60 minutes in the ultrasound laboratory, and if everything was normal, the patient was transferred to the postoperative ward. The fetus was then monitored by cardiotocography or Doppler ultrasonic fetal heart detector, depending on pregnancy stage. Antibiotic was given routinely for 7 days. After aortic and pulmonary valvuloplasty, digoxin was administered to the mother to improve fetal cardiac function and it was continued until delivery.

Fetal balloon aortic valvuloplasty (fBAV) was considered successful when the balloon crossed the aortic valve, was inflated and deflated at least three times, and forward flow through the aortic valve was larger than before the procedure (

Figure 4). Aortic insufficiency was the additional sign that the valve was dilated, however, its appearance was not necessary to consider the procedure successful.

Fetal balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty (fBPV) was considered successful when the pulmonary valve was perforated with the needle and the guidewire with a balloon was introduced to the pulmonary trunk, the balloon was inflated and deflated at least three times, and the forward flow through the pulmonary valve was larger than before the procedure (

Figure 5).

Fetal balloon atrioseptoplasty (fBAS−) was considered successful when the interatrial septum was punctured with a needle, the balloon was introduced and inflated at least once within the interatrial septum, and left to right flow was visible in the color Doppler image.

Fetal stent placement (fBAS+) in the interatrial septum was considered successful when the interatrial septum was punctured with a needle, the balloon with a stent was introduced into the left atrium, the stent was placed in a proper position within the septum, and left to right flow through the stent was visible in the color Doppler image.

4. Discussion

In terms of the number of patients, the most experienced centers in the world are in Boston and Linz, and our program is the third largest. According to the available literature, in Boston 136 fBAV [

9] and in Linz 92 fBAV [

10] and 35 fBPV [

11] have been performed. Some data regarding FCI are collected in the International Fetal Cardiac Intervention Registry (IFCIR) [

1].

Like in the other centers, the most common FCI procedure was fBAV (94) but in contraty the second most common procedure was interatrial septum opening (19) the third one was fBPV (15). In our series, the most serious complication—procedure-related fetal death—occurred in 8% of cases (10 cases out of all 128 procedures). In our material, fBAV and fBPV carried a similar complication rate, with a procedure-related death rate of only 7% for fBAV and for fBPV. Our prenatal technical results are comparable with the latest publication by Friedman et al. from Boston [

12]—the procedures were technically successful in 101/123 (83%), with a higher technical success rate in the more recent procedures (94% vs. 73%). Our results seem to be much more favorable than the results published in the IFCIR (fetal survival 80% and technical success 81% [

1]), and much better than a recently published national study (78.6% technical success and 32% procedure-related mortality) [

13].

Major complications during fBAV occurred in cases with severe fibroelastosis of the left ventricle, in which thrombus formed in the ventricle following its puncture. Moreover, its function did not improve despite the successful opening of the aortic valve. As in those cases, pre–procedure echocardiography showed very low pressure in the left ventricle; according to recent publications those fetuses probably would no longer be scheduled for FCI [

13].

We have shown that general anesthesia of the mother is not necessary to perform FCI procedures. As far as we know, we are the only center performing FCI in conscious maternal analgosedation, in contrast to protocols described by Tulzer et al. [

8] where general anesthesia of the mother is a routine.

In contrary to Schidlow et al. [

14], who gave medications to the fetus through intramuscular or intracardiac routes, we used (in more than 98% of cases) the intraumbilical route, without any complications. Taking into account that access to the umbilical vein gives the possibility of both precise dosing of the medications and allows performing laboratory diagnostic tests, we assume that in experienced hands it could be the way of choice for fetal anesthesia for FCI. We think that intracardiac drug administration, which carries the risk of an additional damage of the ventricle wall, and consecutive pericardial bleeding should be reserved only for fetal resuscitation, when severe bradycardia prolongs the delivery time of the drugs from the umbilical vein to the heart. The intracardiac route was used by us only in fetuses who required immediate resuscitation due to bradycardia, which did not improve after fluid evacuation from the pericardium.

According to our observations, blood must be evacuated from the pericardial cavity immediately to prevent fetal bradycardia and hemodynamic failure. If pericardial effusion persists, quick formation of the thrombus around the heart occurs, making its evacuation with the needle impossible. We observed that even very small amounts of blood (2–3 mL) in the pericardial cavity of a 20-week fetus significantly decreased chamber filling, causing cardiac insufficiency. Since we started to evacuate pericardial fluid immediately after needle withdrawal, instead of waiting for bradycardia and then giving adrenaline, the necessity of its administration became exceedingly rare, as the fetal heart rate normalized in most cases soon after fluid evacuation. It was not necessary to deliver any baby after the procedure due to hemopericardium or bradycardia, in contrast to what was described by Yoon et al. [

15]. We also learned that it is very difficult to evacuate pericardial effusion by simply withdrawing the 18 G needle from the heart to the pericardial cavity after the FCI. It is mostly caused by an inappropriate (perpendicular) angle between the needle and the wall of the ventricle. Aspiration of the blood causes obstructing of the needle tip by the wall of the ventricle. With growing experience, we were always prepared with another needle (20–21 G) ready to use for decompressing the tamponade. This needle should be introduced into the pericardial cavity parallel to the ventricle wall immediately after diagnosis of pericardial bleeding to allow its sufficient emptying.

The use of a Y-connector while using a 17 G needle was a modification that proved very important because we realized that even excessive fetal bleeding flowing down on the surface of the needle might not have been easily noticed during the procedure.

Contrary to one of the most experienced centers [

16], visualization of the fetal heart and heart puncture were performed by the same person (obstetrician). This is a typical way to perform most ultrasound-guided procedures in our center, and although it is sometimes very demanding, it enabled our obstetrician to gain precise control of the needle position during the entire procedure.

The anterior placenta was a factor limiting the area of the puncture site and the possibility of internal maneuvers with the needle to change fetal position. While inserting the needle through the placenta, one must be careful to avoid unintended damage of the umbilical insertion site and fetal vessels leading to it. Regarding the anterior placenta, needle movements should by extremely limited because of the risk of feto-maternal hemorrhage, bleeding from the placental surface, and abruption.

Routine tocolysis was not necessary after FCI. Only in one case, in which fetal position was not optimal but urgent procedure was necessary, prolonged manipulation with the needle through the anterior placenta was performed in order to change the position of the fetus. The procedure was complicated with contractions and then placental abruption.

In our material, in most cases FCI did not influence the time and mode of delivery. The median gestational age at delivery after fBAV, fBPV, and fBAS+ was 39 weeks. In cases of fetal atrioseptoplasty, the median gestational age at delivery was lower due to associated heart failure and polyhydramnios. In our hospital, neither previous prenatal cardiac intervention nor fetal cardiac defect were indications for cesarean section (CS), which was performed only due to obstetrical reasons. The rate of CS in our center was 40% of fBAV and 38% for all procedures, in contrast to 70% CS for all procedures and 67% CS for fBAV when the delivery was in another center.