Rapid Whole-Exome Sequencing as a Diagnostic Tool in a Neonatal/Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients Recruitment

2.2. Genetic Analysis

2.3. WES Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients

3.2. Genetic Findings in WES

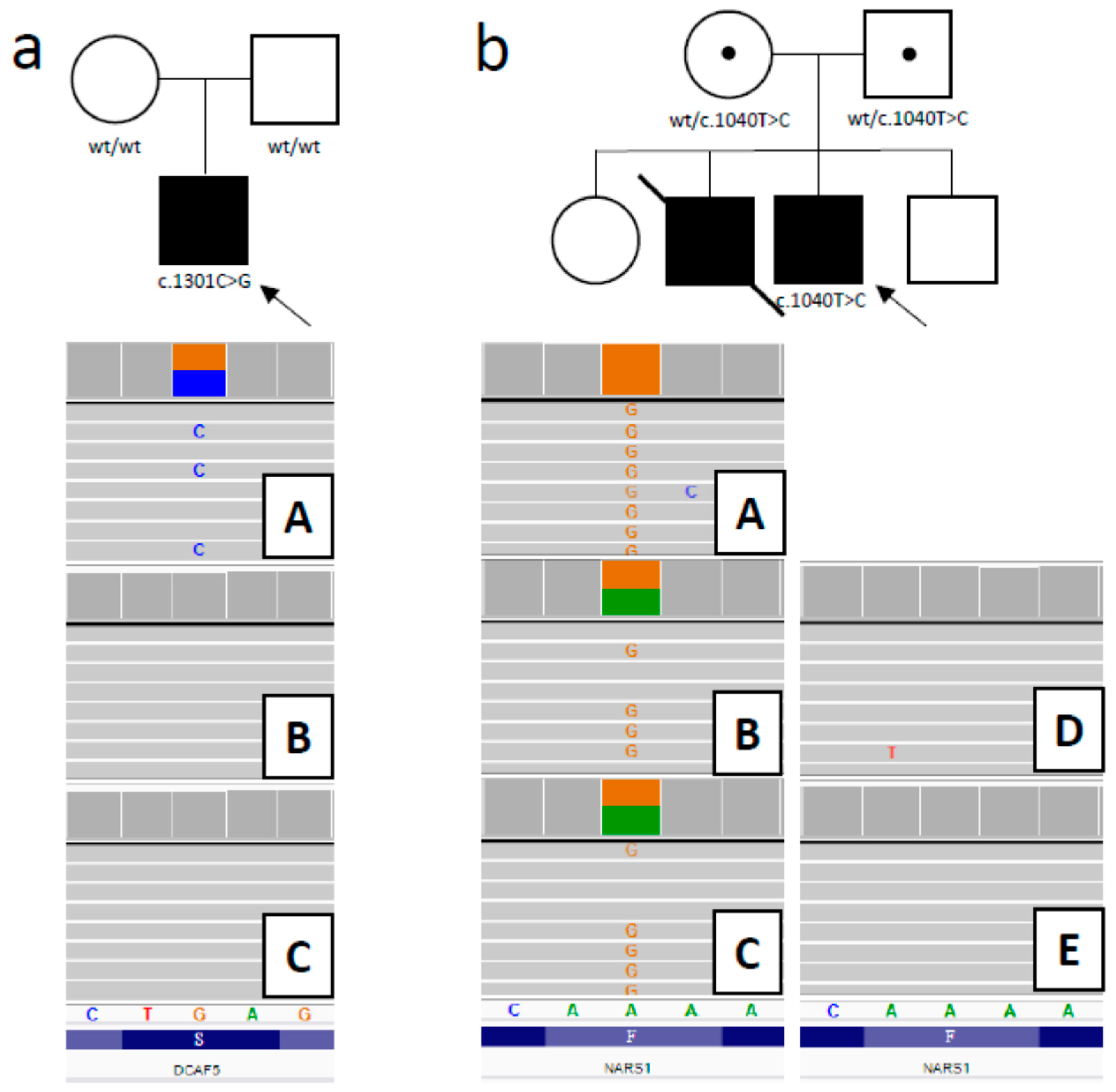

3.2.1. DCAF5 Variant

3.2.2. NARS1 Variant

3.2.3. NFASC Variant

4. Discussion

Impact of WES on Clinical Management

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCandless, S.E.; Brunger, J.W.; Cassidy, S.B. The burden of genetic disease on inpatient care in a children’s hospital. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 74, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orphadata. Available online: http://www.orphadata.org/cgi-bin/index.php (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- OMIM–Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Available online: https://www.omim.org/ (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Borghesi, A.; Mencarelli, M.A.; Memo, L.; Ferrero, G.B.; Bartuli, A.; Genuardi, M.; Stronati, M.; Villani, A.; Renieri, A.; Corsello, G.; et al. Intersociety policy statement on the use of whole-exome sequencing in the critically ill newborn infant. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2017, 43, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrikin, J.E.; Cakici, J.A.; Clark, M.M.; Willig, L.K.; Sweeney, N.M.; Farrow, E.G.; Saunders, C.J.; Thiffault, I.; Miller, N.A.; Zellmer, L.; et al. The NSIGHT1-randomized controlled trial: Rapid whole-genome sequencing for accelerated etiologic diagnosis in critically ill infants. NPJ Genom. Med. 2018, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.E.; du Souich, C.; Dragojlovic, N.; CAUSES Study; RAPIDOMICS Study; Elliott, A.M. Genetic counseling considerations with rapid genome-wide sequencing in a neonatal intensive care unit. J. Genet. Couns. 2019, 28, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.M.; Stark, Z.; Farnaes, L.; Tan, T.Y.; White, S.M.; Dimmock, D.; Kingsmore, S.F. Meta-analysis of the diagnostic and clinical utility of genome and exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in children with suspected genetic diseases. NPJ Genom. Med. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charng, W.-L.; Karaca, E.; Akdemir, Z.C.; Gambin, T.; Atik, M.M.; Gu, S.; Posey, J.E.; Jhangiani, S.N.; Muzny, D.M.; Doddapaneni, H.; et al. Exome sequencing in mostly consanguineous Arab families with neurologic disease provides a high potential molecular diagnosis rate. BMC Med. Genom. 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Z.; Tan, T.Y.; Chong, B.; Brett, G.R.; Yap, P.; Walsh, M.; Yeung, A.; Peters, H.; Mordaunt, D.; Cowie, S.; et al. A prospective evaluation of whole-exome sequencing as a first-tier molecular test in infants with suspected monogenic disorders. Genet. Med. 2016, 18, 1090–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarailo-Graovac, M.; Shyr, C.; Ross, C.J.; Horvath, G.A.; Salvarinova, R.; Ye, X.C.; Zhang, L.-H.; Bhavsar, A.P.; Lee, J.J.Y.; Drögemöller, B.I.; et al. Exome Sequencing and the Management of Neurometabolic Disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.Y.; Dillon, O.J.; Stark, Z.; Schofield, D.; Alam, K.; Shrestha, R.; Chong, B.; Phelan, D.; Brett, G.R.; Creed, E.; et al. Diagnostic impact and cost-effectiveness of whole-exome sequencing for ambulant children with suspected monogenic conditions. JAMA Pediatri. 2017, 171, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestek-Boukhibar, L.; Clement, E.; Jones, W.D.; Drury, S.; Ocaka, L.; Gagunashvili, A.; Le Quesne Stabej, P.; Bacchelli, C.; Jani, N.; Rahman, S.; et al. Rapid Paediatric Sequencing (RaPS): Comprehensive real-life workflow for rapid diagnosis of critically ill children. J. Med. Genet. 2018, 55, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydzanicz, M.; Wachowska, M.; Cook, E.C.; Lisowski, P.; Kuźniewska, B.; Szymańska, K.; Diecke, S.; Prigione, A.; Szczałuba, K.; Szybińska, A.; et al. Novel calcineurin A (PPP3CA) variant associated with epilepsy, constitutive enzyme activation and downregulation of protein expression. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 27, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohse, M.; Bolger, A.M.; Nagel, A.; Fernie, A.R.; Lunn, J.E.; Stitt, M.; Usadel, B. RobiNA: A user-friendly, integrated software solution for RNA-Seq-based transcriptomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W622–W627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faust, G.G.; Hall, I.M. SAMBLASTER: Fast duplicate marking and structural variant read extraction. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2503–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The genome analysis toolkit: A mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrison, E.; Marth, G. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1207.3907. [Google Scholar]

- Poplin, R.; Chang, P.-C.; Alexander, D.; Schwartz, S.; Colthurst, T.; Ku, A.; Newburger, D.; Dijamco, J.; Nguyen, N.; Afshar, P.T.; et al. A universal SNP and small-indel variant caller using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibulskis, K.; Lawrence, M.S.; Carter, S.L.; Sivachenko, A.; Jaffe, D.; Sougnez, C.; Gabriel, S.; Meyerson, M.; Lander, E.S.; Getz, G. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layer, R.M.; Chiang, C.; Quinlan, A.R.; Hall, I.M. LUMPY: A probabilistic framework for structural variant discovery. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talevich, E.; Shain, A.H.; Botton, T.; Bastian, B.C. CNVkit: Genome-wide copy number detection and visualization from targeted DNA sequencing. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016, 12, e1004873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, W.; Gil, L.; Hunt, S.E.; Riat, H.S.; Ritchie, G.R.S.; Thormann, A.; Flicek, P.; Cunningham, F. The ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smigielski, E.M.; Sirotkin, K.; Ward, M.; Sherry, S.T. dbSNP: A database of single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wu, C.; Li, C.; Boerwinkle, E. dbNSFP v3.0: A one-stop database of functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Hum. Mutat. 2016, 37, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karczewski, K.J.; Francioli, L.C.; Tiao, G.; Cummings, B.B.; Alföldi, J.; Wang, Q.; Collins, R.L.; Laricchia, K.M.; Ganna, A.; Birnbaum, D.P.; et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature 2020, 581, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, M.J.; Lee, J.M.; Riley, G.R.; Jang, W.; Rubinstein, W.S.; Church, D.M.; Maglott, D.R. ClinVar: Public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D980–D985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenson, P.D.; Ball, E.V.; Mort, M.; Phillips, A.D.; Shiel, J.A.; Thomas, N.S.T.; Abeysinghe, S.; Krawczak, M.; Cooper, D.N. Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD): 2003 update. Hum. Mutat. 2003, 21, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopanos, C.; Tsiolkas, V.; Kouris, A.; Chapple, C.E.; Albarca Aguilera, M.; Meyer, R.; Massouras, A. VarSome: The human genomic variant search engine. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1978–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.C.; Berg, J.S.; Grody, W.W.; Kalia, S.S.; Korf, B.R.; Martin, C.L.; McGuire, A.L.; Nussbaum, R.L.; O’Daniel, J.M.; Ormond, K.E.; et al. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet. Med. 2013, 15, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varsome. The Human Genomics Community. Available online: https://varsome.com/ (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- GnomAD. Available online: https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/ (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Smigiel, R.; Sherman, D.L.; Rydzanicz, M.; Walczak, A.; Mikolajkow, D.; Krolak-Olejnik, B.; Kosinska, J.; Gasperowicz, P.; Biernacka, A.; Stawinski, P.; et al. Homozygous mutation in the Neurofascin gene affecting the glial isoform of Neurofascin causes severe neurodevelopment disorder with hypotonia, amimia and areflexia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 3669–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.A.; Farrow, E.G.; Gibson, M.; Willig, L.K.; Twist, G.; Yoo, B.; Marrs, T.; Corder, S.; Krivohlavek, L.; Walter, A.; et al. A 26-hour system of highly sensitive whole genome sequencing for emergency management of genetic diseases. Genome Med. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnaes, L.; Hildreth, A.; Sweeney, N.M.; Clark, M.M.; Chowdhury, S.; Nahas, S.; Cakici, J.A.; Benson, W.; Kaplan, R.H.; Kronick, R.; et al. Rapid whole-genome sequencing decreases infant morbidity and cost of hospitalization. NPJ Genom. Med. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, E.F.; Clark, M.M.; Farnaes, L.; Williams, M.R.; Perry, J.C.; Ingulli, E.G.; Sweeney, N.M.; Doshi, A.; Gold, J.J.; Briggs, B.; et al. Rapid whole genome sequencing has clinical utility in children in the PICU. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 20, 1007–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Diemen, C.C.; Kerstjens-Frederikse, W.S.; Bergman, K.A.; de Koning, T.J.; Sikkema-Raddatz, B.; van der Velde, J.K.; Abbott, K.M.; Herkert, J.C.; Löhner, K.; Rump, P.; et al. Rapid targeted genomics in critically Ill newborns. Pediatrics 2017, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okazaki, T.; Murata, M.; Kai, M.; Adachi, K.; Nakagawa, N.; Kasagi, N.; Matsumura, W.; Maegaki, Y.; Nanba, E. Clinical diagnosis of mendelian disorders using a comprehensive gene-targeted panel test for next-generation sequencing. Yonago Acta Med. 2016, 59, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; Pammi, M.; Saronwala, A.; Magoulas, P.; Ghazi, A.R.; Vetrini, F.; Zhang, J.; He, W.; Dharmadhikari, A.V.; Qu, C.; et al. Use of exome sequencing for infants in intensive care units: Ascertainment of severe single-gene disorders and effect on medical management. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, e173438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, I.T.; Showalter, M.R.; Fiehn, O. Inborn errors of metabolism in the era of untargeted metabolomics and lipidomics. Metabolites 2019, 9, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, C.R.; van Karnebeek, C.D.M.; Vockley, J.; Blau, N. A proposed nosology of inborn errors of metabolism. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, S.; Salpietro, V.; Malintan, N.; Poncelet, M.; Kriouile, Y.; Fortuna, S.; de Zorzi, R.; Payne, K.; Henderson, L.B.; Cortese, A.; et al. Biallelic mutations in neurofascin cause neurodevelopmental impairment and peripheral demyelination. Brain 2019, 142, 2948–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.G.; Schimmel, P.; Kim, S. Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases and their connections to disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 11043–11049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuguchi, T.; Nakashima, M.; Kato, M.; Yamada, K.; Okanishi, T.; Ekhilevitch, N.; Mandel, H.; Eran, A.; Toyono, M.; Sawaishi, Y.; et al. PARS2 and NARS2 mutations in infantile-onset neurodegenerative disorder. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 62, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehl-Jaschkowitz, B.; Vanakker, O.M.; de Paepe, A.; Menten, B.; Martin, T.; Weber, G.; Christmann, A.; Krier, R.; Scheid, S.; McNerlan, S.E.; et al. Deletions in 14q24.1q24.3 are associated with congenital heart defects, brachydactyly, and mild intellectual disability. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2014, 164A, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angers, S.; Li, T.; Yi, X.; Maccoss, M.; Moon, R.; Zheng, N. Molecular architecture and assembly of the DDB1-CUL4A ubiquitin ligase machinery. Nature 2006, 443, 590–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Zhou, P. DCAFs, the missing link of the CUL4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Cell 2007, 26, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarpey, P.S.; Raymond, F.L.; O’Meara, S.; Edkins, S.; Teague, J.; Butler, A.; Dicks, E.; Stevens, C.; Tofts, C.; Avis, T.; et al. Mutations in CUL4B, which encodes a ubiquitin E3 ligase subunit, cause an X-linked mental retardation syndrome associated with aggressive outbursts, seizures, relative macrocephaly, central obesity, hypogonadism, pes cavus, and tremor. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 80, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria (All the Following) | Exclusion Criteria (Any of the Following) |

|---|---|

| A critically ill newborn or infant in the ICU with severe unexplained neurological signs that started suddenly, but the following conditions also will be considered: metabolic failure of unknown origin; severe multi-organ disease of unknown pathogenesis, especially in case of poor responsiveness to standard treatment; severe congenital malformations that are not consistent with any known syndrome; other unexplained or unclear acute conditions. | Presence of symptoms suggesting a concrete, known genetic syndrome possible to diagnose using standard diagnostic methods (for example, Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome or congenital metabolic defect diagnosed in a newborn screening test performed in Poland (MS/MS, 25 inborn errors of metabolism). |

| Based on pre- and perinatal history, a non-genetic etiology can explain the disease, and/or is confirmed with laboratory results/imaging techniques. | |

| Consent form obtained from both parents for blood sampling and genetic research tests of the child and themselves. | Lack of consent form of one of the proband’s parents for blood sampling and genetic research test. |

| ID/Sex | Age of Onset/Age at Testing | Main Symptoms | Rapid-WES as First-Tier/Molecular Confirmation in WES | Gene/Inheritance | Variant(s) hg38 | Pathogenicity Verdict according to ACMG Classification (https://varsome.com) | Disease/ OMIM | Impact on Clinical Management | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/M | 3rd/ 7th week of life | RF; distal contractures; | N/Y | SCO2 AR | compound heterozygote NM_005138.3: | Leigh syndrome/604377 | Death before diagnosis | Y | |

| chr22:050524395-C > CTGAGTCACTGCTGCATGCT c.16_17insAGCATGCAGCAGTGACTCA; p.(Arg6GlnfsTer82) | Pathogenic | ||||||||

| chr22: 50523994-C > T c.418G > A; p.(Glu140Lys) | Pathogenic | ||||||||

| 2/M | 5th/ 8th month of life | RF; FH; D; MA; | Y/Y | SCO2 AR | homozygote NM_005138.3: chr22: 50523994-C > T c.418G > A; p.(Glu140Lys) | Pathogenic | Leigh syndrome/604377 | Palliative hospice care | Y |

| 3/M | 3rd/ 10th month of life | RF; FH; | N/Y | POLG AR | homozygote NM_001126131.2: chr15:89320885-G > C c.2862C > G; p.(Ile954Met) | Likely Pathogenic | Alpers syndrome/203700 | Palliative hospice care | Y |

| 4/F | Prenatal period/ 3rd week of life | RF, arthrogryposis; D; | N/Y | GBE1 AR | compound heterozygote NM_005158.3: | Glycogen storage disease IV - perinatal severe form (Anderson syndrome)/232500 | Death before diagnosis | Y | |

| Chr3:81648854-A > G c.691+2T > C; p.- | Pathogenic | ||||||||

| chr3:81499187-C > T c.1975G > A; p.(Gly659Arg) | Uncertain Significance | ||||||||

| 5/F | 1st day of life/ 2nd month of life | RF; MA; D; | N/Y | PC AR | compound heterozygote NM_022172.3: | Pyruvate carboxylase deficiency/ 216150 | Death before diagnosis | Y | |

| chr11:66866282-G > A c.1090C > T; p.(Gln364Ter) | Pathogenic | ||||||||

| chr11:66863920-C > G c.1222G > C; p.(Asp408His) | Pathogenic | ||||||||

| 6/M | 2nd/ 3rd month of life | RF; D; epilepsy; brain atrophy | Y/Y | AIFM1 XLR | hemizygote NM_004208.3: chrX:130133411-C > G c.1350G > C; p.(Arg450Ser) | Pathogenic | Combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 6/ 300816 | Palliative care, DNR protocol | Y |

| 7/F | 4th/ 16th month of life | RF; | Y/Y | ABCA3 AR | homozygote NM_001089.3: chr16:002323532-C > T c.604G > A; p.(Gly202Arg) | Uncertain Significance | Surfactant metabolism dysfunction, pulmonary, 3 (SMPD3)/ 610921 | Lung transplantation | N |

| 8/F | At birth/ 2nd month of life | RF, arthrogryposis; D; FH; | N/Y | MAGEL2 AD | de novo NM_019066.4: chr15:23644849-C > T c.2894G > A; p.(Trp965Ter) | Pathogenic | Schaaf-Yang syndrome/ 615547 | symptomatic treatment, multidisciplinary care | N |

| 9/F | 1st/ 8th month of life | FH; severe delayed psychomotor development; D; | Y/Y | NALCN AR | compound heterozygote NM_052867.2: | Hypotonia, infantile, with psychomotor retardation and characteristic facies 1 (IHPRF1)/ 611549 | symptomatic treatment, multidisciplinary care | N | |

| chr13:101111216-G > A c.2203C > T; p.(Arg735Ter) | Pathogenic | ||||||||

| Chr13:101229388-C > A c.1626+5G > T; p- | Uncertain Significance (note: predicted to strongly affect splicing -ADA Score 0.9997. If this is taken into account the verdict is „pathogenic”). | ||||||||

| 10/F | At birth/ 1st month of life | RF; scleroderma; | N/Y | ACTA1 AD | de novo NM_001100.3: Chr1:229432567-C > A c.443G > T, p.(Gly148Val) | Likely Pathogenic | Nemaline myopathy AD/ 161800 | Death before diagnosis | Y |

| 11/M | Prenatal period/ 1st week of life | scleroderma edema; | N/N | non-diagnostic | - | lack | Death before diagnosis | Y | |

| 12/M | 1st/ 9th day of live | RF; MA; elevated alanine | Y/Y | TRMT10C AR | compound heterozygote NM_017819.4: | Mitochondrial disease (Combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 30)/ 616974 | Palliative care, DNR protocol | Y | |

| Chr3:101565509-T > C c.728T > C; p.(Ile243Thr) | Uncertain Significance | ||||||||

| Chr3:101565164-C > CA c.393_3394insA; p.(Tyr132IlefsTer15) | Likely pathogenic | ||||||||

| 13/F | At birth/ 3rd day of life | RF; F; | N/Y | NFASC AR | homozygote NM_015090.3: Chr1:204984059-C > T c.2491C > T; p.(Arg831Ter) | Pathogenic | New disorder described (Neurodevelopmental disorder with central and peripheral motor dysfunction)/ 618356 | Palliative care, DNR protocol | Y |

| 14/M | 11th/ 11th month of life | RF; encephalopathy; sister died earlier with similar signs; | Y/Y | NARS1 AR | homozygote NM_004539.4: Chr18:57606713 -A > G c.1040T > C; p.(Phe347Ser) | Uncertain Significance | A new disease suspected/108410 | Palliative care, DNR protocol | N |

| 15/M | 1st week of life/ 4th month of life | RF; F; D; | Y/Y | DCAF5 AD | de novo NM_003861.3: 14:069055385-G > C c.1301C > G; p.(Ser434Ter) | Pathogenic | A new disease suspected/603812 | Palliative care, DNR protocol | Y |

| 16/M | 2nd/ 7th day of life | Hyperammonemia; RF; | Y/N | non-diagnostic | - | lack | Death before diagnosis | Y | |

| 17/M | Prenatal period/ 1st month of life | General eodema; seizures; | N/N | non-diagnostic | - | lack | Death before diagnosis | Y | |

| 18/M | 2nd/ 8th month of life | Psychomotor delay, severe deterioration of general condition | Y/Y | SCO2 AR | homozygote NM_005138.3: chr22: 50523994-C > T c.418G > A; p.(Glu140Lys) | Pathogenic | Leigh syndrome/604377 | Palliative hospice care | Y |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Śmigiel, R.; Biela, M.; Szmyd, K.; Błoch, M.; Szmida, E.; Skiba, P.; Walczak, A.; Gasperowicz, P.; Kosińska, J.; Rydzanicz, M.; et al. Rapid Whole-Exome Sequencing as a Diagnostic Tool in a Neonatal/Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2220. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9072220

Śmigiel R, Biela M, Szmyd K, Błoch M, Szmida E, Skiba P, Walczak A, Gasperowicz P, Kosińska J, Rydzanicz M, et al. Rapid Whole-Exome Sequencing as a Diagnostic Tool in a Neonatal/Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(7):2220. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9072220

Chicago/Turabian StyleŚmigiel, Robert, Mateusz Biela, Krzysztof Szmyd, Michal Błoch, Elżbieta Szmida, Paweł Skiba, Anna Walczak, Piotr Gasperowicz, Joanna Kosińska, Małgorzata Rydzanicz, and et al. 2020. "Rapid Whole-Exome Sequencing as a Diagnostic Tool in a Neonatal/Pediatric Intensive Care Unit" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 7: 2220. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9072220

APA StyleŚmigiel, R., Biela, M., Szmyd, K., Błoch, M., Szmida, E., Skiba, P., Walczak, A., Gasperowicz, P., Kosińska, J., Rydzanicz, M., Stawiński, P., Biernacka, A., Zielińska, M., Gołębiowski, W., Jalowska, A., Ohia, G., Głowska, B., Walas, W., Królak-Olejnik, B., ... Płoski, R. (2020). Rapid Whole-Exome Sequencing as a Diagnostic Tool in a Neonatal/Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(7), 2220. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9072220