Benzodiazepines Reduce Relapse and Recurrence Rates in Patients with Psychotic Depression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

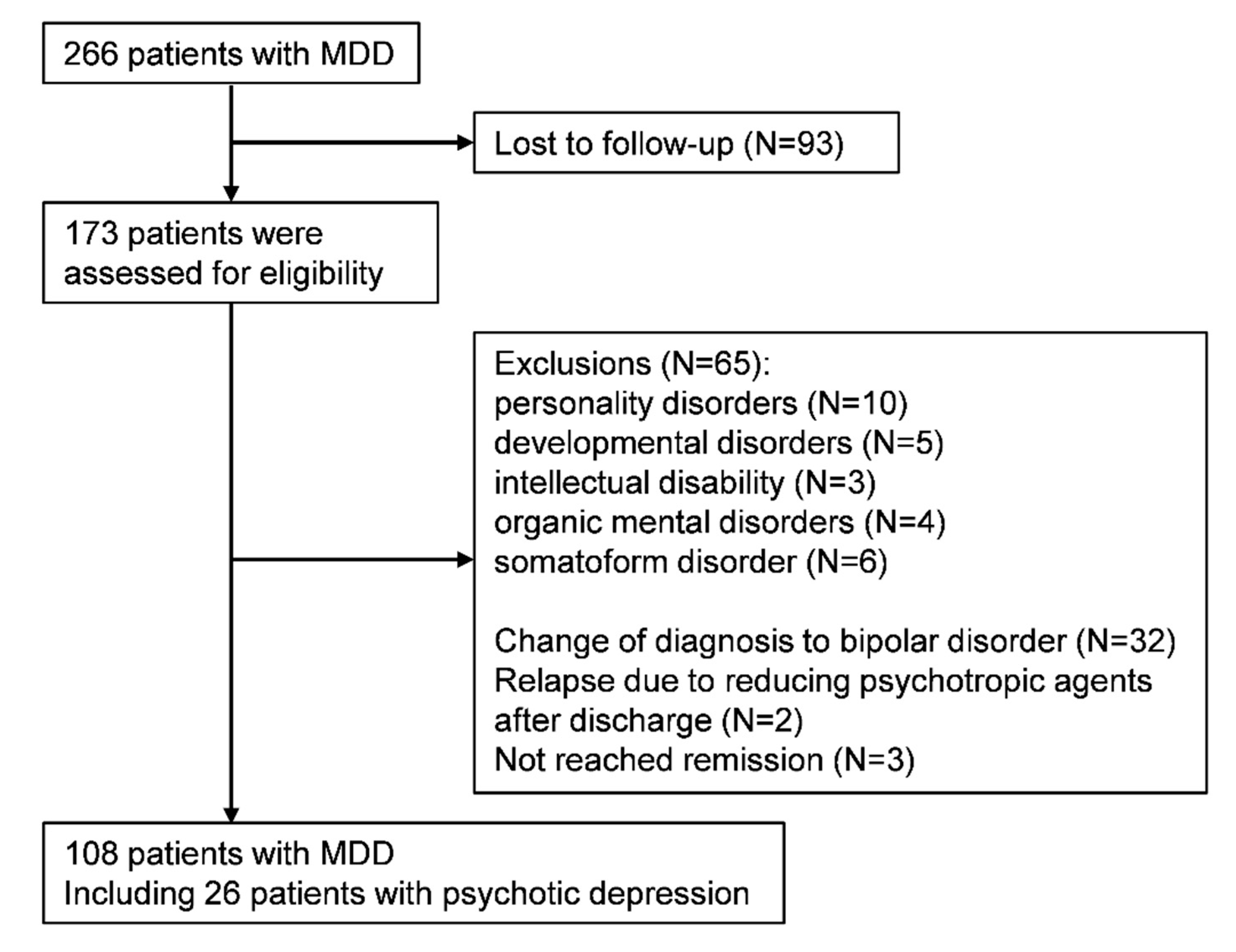

2.2. Study Cohort

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Benzodiazepine Score

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

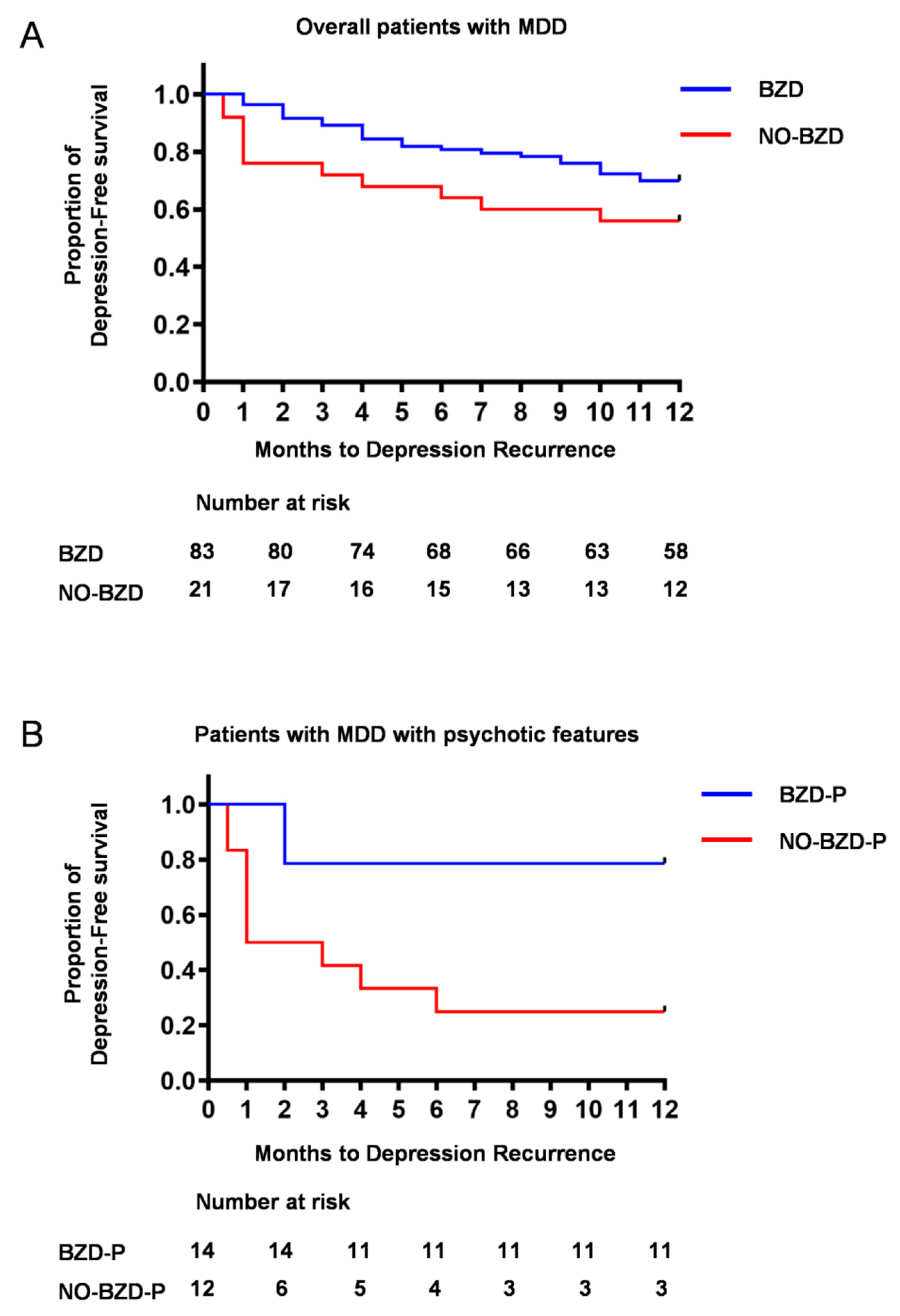

3.2. Time to Depression Relapse/Recurrence

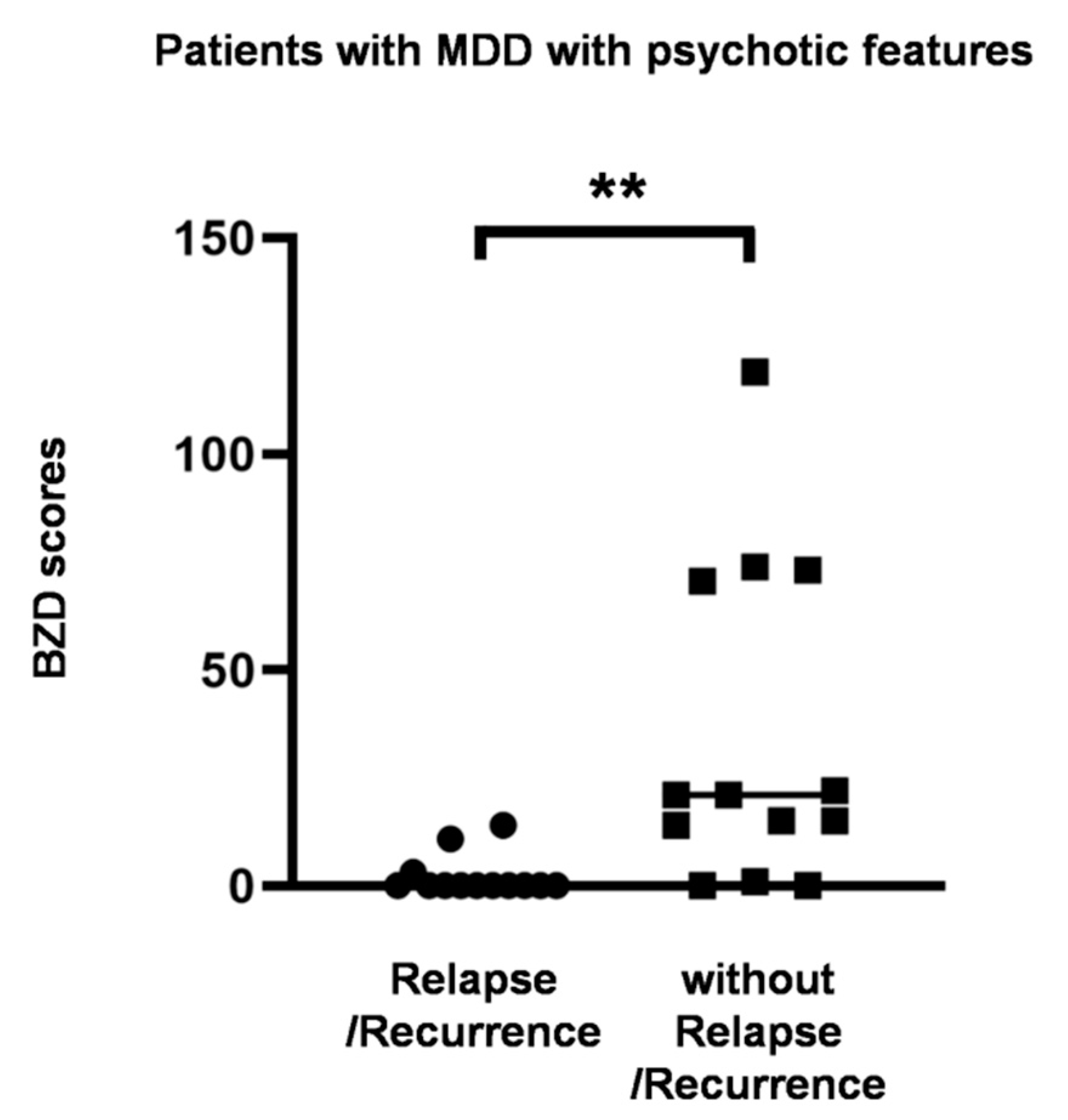

3.3. Dose-Dependent Effect of Benzodiazepines on Time to Depression Relapse/Recurrence

3.4. Relapse/Recurrence in Psychotic Depression

3.5. A Case Report

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keller, M.B.; Trivedi, M.H.; Thase, M.E.; Shelton, R.C.; Kornstein, S.G.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Friedman, E.S.; Gelenberg, A.J.; Kocsis, J.H.; Dunner, D.L.; et al. The prevention of recurrent episodes of depression with venlafaxine for two years (prevent) study: Outcomes from the 2-year and combined maintenance phases. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007, 68, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimherr, F.W.; Amsterdam, J.D.; Quitkin, F.M.; Rosenbaum, J.F.; Fava, M.; Zajecka, J.; Beasley, C.M., Jr.; Michelson, D.; Roback, P.; Sundell, K. Optimal length of continuation therapy in depression: A prospective assessment during long-term fluoxetine treatment. Am. J. Psychiatry 1998, 155, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, K.; Lau, W.K.; Sim, J.; Sum, M.Y.; Baldessarini, R.J. Prevention of relapse and recurrence in adults with major depressive disorder: Systematic review and meta-analyses of controlled trials. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lader, M. Benzodiazepines revisited--will we ever learn? Addiction 2011, 106, 2086–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumming, R.G.; Le Couteur, D.G. Benzodiazepines and risk of hip fractures in older people: A review of the evidence. CNS Drugs 2003, 17, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billioti de Gage, S.; Begaud, B.; Bazin, F.; Verdoux, H.; Dartigues, J.F.; Peres, K.; Kurth, T.; Pariente, A. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: Prospective population based study. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2012, 345, e6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billioti de Gage, S.; Moride, Y.; Ducruet, T.; Kurth, T.; Verdoux, H.; Tournier, M.; Pariente, A.; Begaud, B. Benzodiazepine use and risk of alzheimer’s disease: Case-control study. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2014, 349, g5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weich, S.; Pearce, H.L.; Croft, P.; Singh, S.; Crome, I.; Bashford, J.; Frisher, M. Effect of anxiolytic and hypnotic drug prescriptions on mortality hazards: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2014, 348, g1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. National institute for health and clinical excellence: Guidance. In Depression: The Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (Updated Edition); British Psychological Society: Leicester, UK; Copyright (c) The British Psychological Society & The Royal College of Psychiatrists: Leicester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, Y.; Takeshima, N.; Hayasaka, Y.; Tajika, A.; Watanabe, N.; Streiner, D.; Furukawa, T.A. Antidepressants plus benzodiazepines for adults with major depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 6, Cd001026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benasi, G.; Guidi, J.; Offidani, E.; Balon, R.; Rickels, K.; Fava, G.A. Benzodiazepines as a monotherapy in depressive disorders: A systematic review. Psychother. Psychosom. 2018, 87, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, G.A.; Sturmer, T.; Gaynes, B.N.; Pate, V.; Miller, M. Simultaneous antidepressant and benzodiazepine new use and subsequent long-term benzodiazepine use in adults with depression, united states, 2001–2014. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manthey, L.; Giltay, E.J.; van Veen, T.; Neven, A.K.; Zitman, F.G.; Penninx, B.W. Determinants of initiated and continued benzodiazepine use in the netherlands study of depression and anxiety. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 31, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inada, T.; Inagaki, A. Psychotropic dose equivalence in japan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 69, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, S.H.; Lam, R.W.; McIntyre, R.S.; Tourjman, S.V.; Bhat, V.; Blier, P.; Hasnain, M.; Jollant, F.; Levitt, A.J.; MacQueen, G.M.; et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (canmat) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: Section 3. Pharmacological treatments. Can. J. Psychiatry Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2016, 61, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, R.S.; Sanacora, G.; Krystal, J.H. Altered connectivity in depression: Gaba and glutamate neurotransmitter deficits and reversal by novel treatments. Neuron 2019, 102, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, G.; van der Veen, J.W.; Tumonis, T.; Meyers, N.; Shen, J.; Drevets, W.C. Reduced prefrontal glutamate/glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid levels in major depression determined using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, R.B.; Shungu, D.C.; Mao, X.; Nestadt, P.; Kelly, C.; Collins, K.A.; Murrough, J.W.; Charney, D.S.; Mathew, S.J. Amino acid neurotransmitters assessed by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy: Relationship to treatment resistance in major depressive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 65, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fee, C.; Banasr, M.; Sibille, E. Somatostatin-positive gamma-aminobutyric acid interneuron deficits in depression: Cortical microcircuit and therapeutic perspectives. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 82, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T.; Jefferson, S.J.; Hooper, A.; Yee, P.H.; Maguire, J.; Luscher, B. Disinhibition of somatostatin-positive gabaergic interneurons results in an anxiolytic and antidepressant-like brain state. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, F.; Fatouros-Bergman, H.; Goiny, M.; Malmqvist, A.; Piehl, F.; Cervenka, S.; Collste, K.; Victorsson, P.; Sellgren, C.M.; Flyckt, L.; et al. Csf gaba is reduced in first-episode psychosis and associates to symptom severity. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 1244–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dold, M.; Bartova, L.; Kautzky, A.; Porcelli, S.; Montgomery, S.; Zohar, J.; Mendlewicz, J.; Souery, D.; Serretti, A.; Kasper, S. Psychotic features in patients with major depressive disorder: A report from the european group for the study of resistant depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2019, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fava, G.A.; Ruini, C.; Rafanelli, C.; Finos, L.; Conti, S.; Grandi, S. Six-year outcome of cognitive behavior therapy for prevention of recurrent depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 1872–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balon, R.; Starcevic, V.; Silberman, E.; Cosci, F.; Dubovsky, S.; Fava, G.A.; Nardi, A.E.; Rickels, K.; Salzman, C.; Shader, R.I.; et al. The rise and fall and rise of benzodiazepines: A return of the stigmatized and repressed. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2020, 42, 243–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Overall Patients with MDD (N = 108) | Patients with MDD with Psychotic Features (N = 26) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | BZD (N = 83: Patients Who Received BZDs) | NO-BZD (N = 25: Patients Who Did Not Received BZDs) | BZD-P (n = 14: Patients Who Received BZDs) | NO-BZD-P (n = 12: Patients Who Did Not Received BZDs) |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Female sex | 57 (68.7%) | 17 (68.0%) | 11 (78.5%) | 10 (83.3%) |

| antidepressants | ||||

| SSRIs | 34 (41.0%) | 11 (44.0%) | 9 (64.3%) | 5 (41.7%) |

| SNRIs | 15 (18.1%) | 7 (28.0%) | 3 (21.4%) | 5 (41.7%) |

| mirtazapine | 36 (43.4%) | 7 (28.0%) | 7 (50.0%) | 3 (25.0%) |

| antipsychotics | 36 (43.4%) | 11 (44.0%) | 7 (50.0%) | 6 (50.0%) |

| olanzapine | 8 (9.6%) | 3 (12.0%) | 2 (14.3%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| quetiapine | 19 (22.9%) | 7 (28.0%) | 4 (28.6%) | 4 (33.3%) |

| mECT | 13 (15.7%) | 11 (44.0%) | 10 (71.4%) | 9 (75.0%) |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| 296.2x | 29 (34.9%) | 9 (36.0%) | ||

| 296.21/296.22 | 19 (22.9%) | 2 (8.0%) | ||

| 296.23 | 5 (6.0%) | 1 (4.0%) | ||

| 296.24 | 4 (4.8%) | 6 (24.0%) | 4 (28.6%) | 6 (50.0%) |

| 296.3x | 54 (65.1%) | 16 (64.0%) | ||

| 296.31/296.32 | 32 (38.6%) | 5 (20.0%) | ||

| 296.33 | 8 (9.6%) | 5 (20.0%) | ||

| 296.34 | 10 (12.0%) | 6 (24.0%) | 10 (71.4%) | 6 (50.0%) |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| age | 63.9 (13.2) | 62.5 (16.4) | 71.2 (9.79) | 72.7 (10.0) |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

| Period from onset | 6.5 (2.0~13.8) | 4.0 (0.5~12.5) | 7.0 (3.0~14.0) | 3.0 (0.25~12.8) |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| HAM-D | 23.5 (5.1) | 26.9 (7.28) | 33.1 (2.8) | 32.6 (2.7) |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

| Length of hospitalization (months) | 2.0 (2–3) | 2.0 (1.5–3) | 3.0 (2–3) | 2.75 (2–3.5) |

| Parameter | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| benzodiazepines | 8.340 | 1.621–41.92 | 0.011 |

| SSRI | 0.313 | 0.028–3.424 | 0.341 |

| SNRI | 0.488 | 0.043–5.504 | 0.561 |

| mirtazapine | 5.784 | 0.680–49.26 | 0.108 |

| olanzapine | 1.125 | 0.244–5.189 | 0.880 |

| quetiapine | 3.552 | 0.614–20.57 | 0.157 |

| Patients with MDD with Psychotic Features (N = 26) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Relapse/Recurrence (N = 13) | Without Relapse/Recurrence (N = 13) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | p-Value | |

| Female sex | 11 (84.6%) | 10 (76.9%) | >0.999 |

| antidepressants | |||

| SSRIs | 7 (53.9%) | 7 (53.9%) | >0.999 |

| SNRIs | 5 (38.5%) | 3 (23.1%) | 0.673 |

| mirtazapine | 2 (15.4%) | 8 (61.5%) | 0.0414 |

| antipsychotics | 8 (61.5%) | 5 (38.5%) | 0.434 |

| olanzapine | 4 (30.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0957 |

| quetiapine | 3 (23.1%) | 5 (38.5%) | 0.673 |

| mECT | 9 (69.2%) | 11 (75.6%) | 0.678 |

| diagnosis | |||

| 296.24 | 5 (38.5%) | 8 (61.4%) | 0.434 |

| 296.34 | 8 (61.4%) | 5 (38.5%) | 0.434 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| age | 75.2 (8.54) | 68.7 (10.1) | 0.0777 |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Period from onset | 2.0 (0.5~11.5) | 5.0 (1.5~14.0) | 0.340 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| HAM-D | 32.8 (2.66) | 32.8 (2.81) | 0.946 |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Duration of hospitalization (months) | 2.5 (2–3) | 3.0 (2–4) | 0.476 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shiwaku, H.; Fujita, M.; Takahashi, H. Benzodiazepines Reduce Relapse and Recurrence Rates in Patients with Psychotic Depression. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061938

Shiwaku H, Fujita M, Takahashi H. Benzodiazepines Reduce Relapse and Recurrence Rates in Patients with Psychotic Depression. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(6):1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061938

Chicago/Turabian StyleShiwaku, Hiroki, Masako Fujita, and Hidehiko Takahashi. 2020. "Benzodiazepines Reduce Relapse and Recurrence Rates in Patients with Psychotic Depression" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 6: 1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061938

APA StyleShiwaku, H., Fujita, M., & Takahashi, H. (2020). Benzodiazepines Reduce Relapse and Recurrence Rates in Patients with Psychotic Depression. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(6), 1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061938