Intraosseous Temperature Change during Installation of Dental Implants with Two Different Surfaces and Different Drilling Protocols: An In Vivo Study in Sheep

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Samples

2.2. Surgical Procedures

- Group A and C (undersized drilling protocol): 3.2 drill and tap drill were subsequently used for the preparation of the coronal 1.5 mm, in order to favor the engagement of the first threads during the implant installment.

- Group B and D (non-undersized drilling protocol): 3.2 drill and tap drill were subsequently used for the entire thickness of the cortical bone.

2.3. Temperature Measurement

2.4. Preparation of Samples

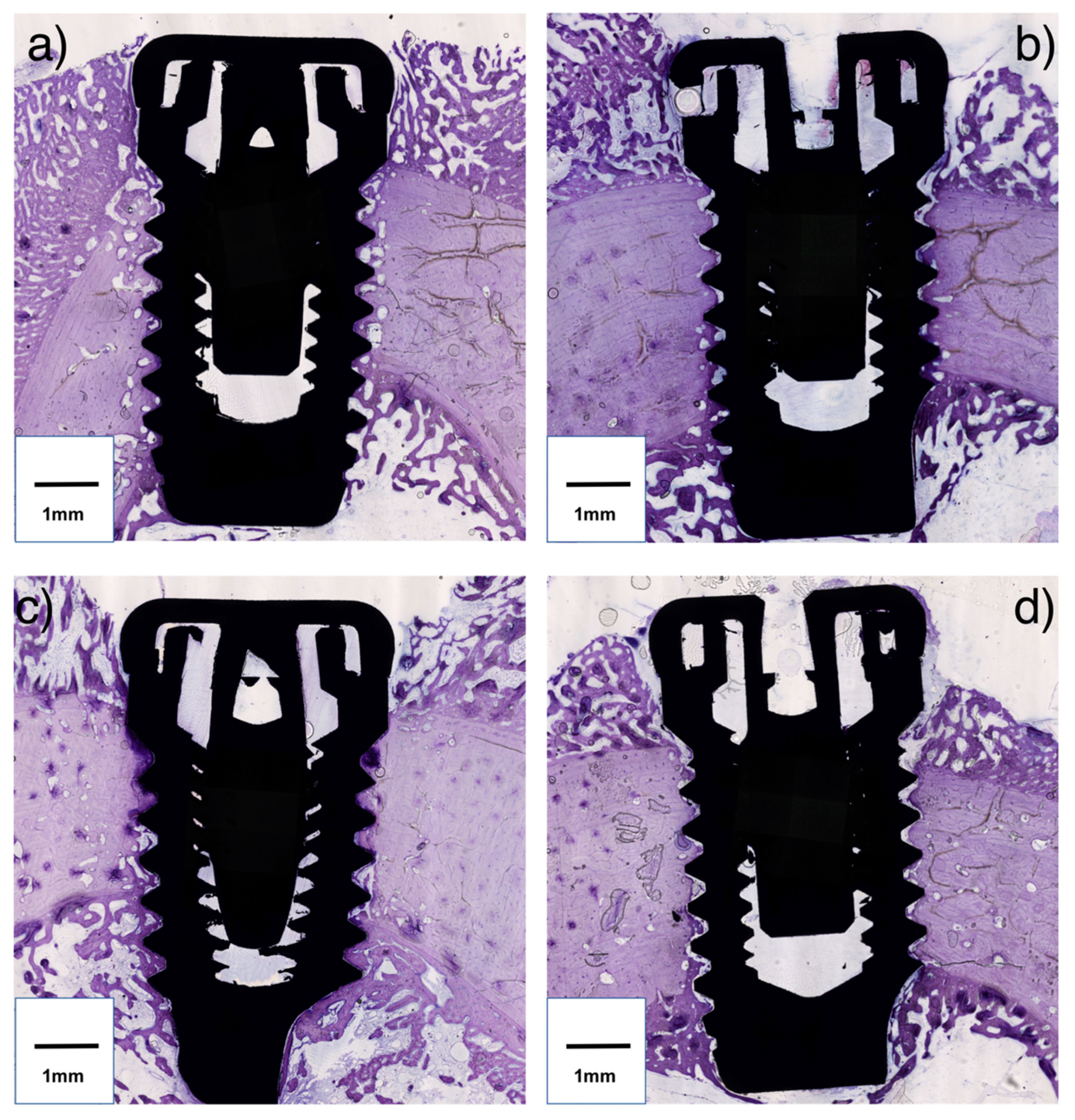

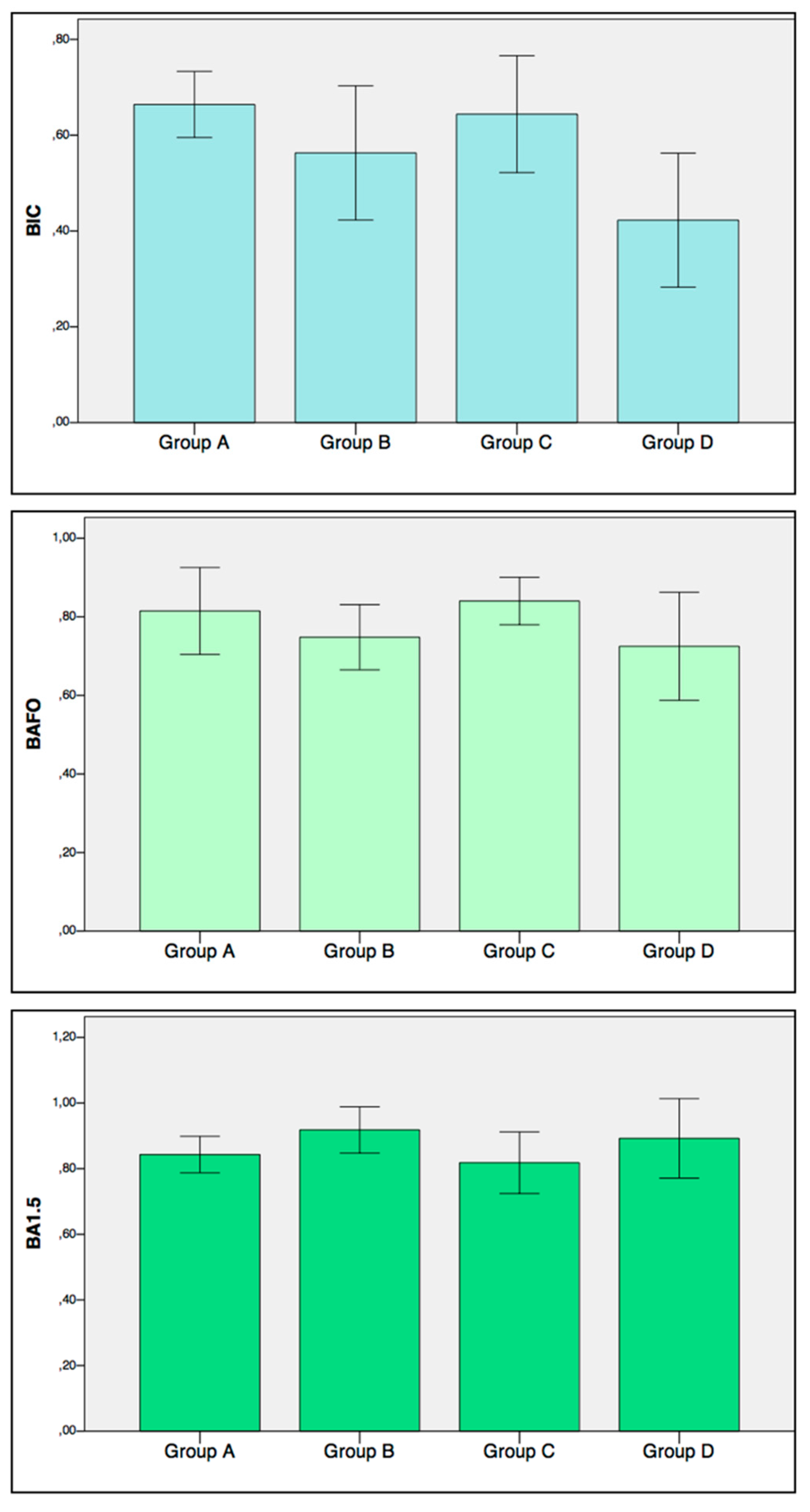

2.5. Histomorphometric Analysis

- Bone-to-implant contact (BIC): On each side of the implant, the percentage of the bone in direct contact with the implant surface in the entire length of the implant placed in the bone was calculated. The mean value of the two sides was used for each implant.

- Bone Area Fraction Occupancy (BAFO): On each side of the implant, the percentage of the area within the implant threads occupied by visibly distinguishable bone was calculated. The mean value of the two sides was used for each implant.

- Bone Area Fraction Occupancy up to 1.5 mm (BA1.5): On each side of the implant a region of interest up to 1.5 mm from the implant outer diameter line was considered (Figure 1c). The percentage of the area occupied by visibly distinguishable bone was calculated. The mean value of the two sides was used for each implant.

2.6. Finite Element Model

2.7. Statistical Methods

3. Results

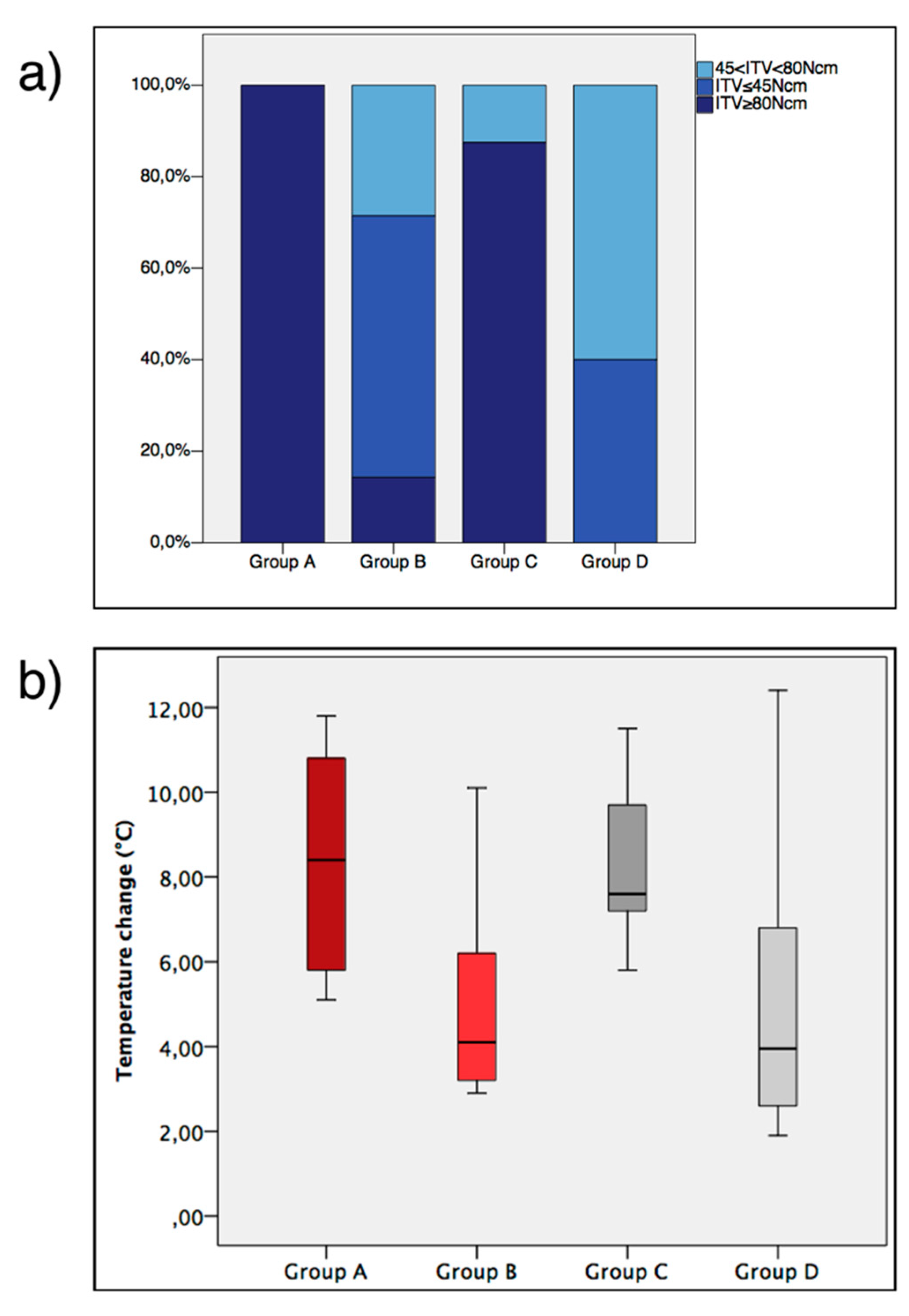

3.1. ITV, General Healing and Temperature

3.2. Histomorphometric Parameters

3.3. Finite Element Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Bone Temperature

4.2. Drilling Protocol

4.3. Surface

4.4. Clinical Applications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Kisch, J.; Albrektsson, T.; Wennerberg, A. A retrospective study on clinical and radiological outcomes of oral implants in patients followed up for a minimum of 20 years. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2018, 20, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donati, M.; Ekestubbe, A.; Lindhe, J.; Wennstrom, J.L. Marginal bone loss at implants with different surface characteristics A 20-year follow-up of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2018, 29, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Kisch, J.; Albrektsson, T.; Wennerberg, A. Factors Influencing Early Dental Implant Failures. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derks, J.; Hakansson, J.; Wennstrom, J.L.; Tomasi, C.; Larsson, M.; Berglundh, T. Effectiveness of implant therapy analyzed in a Swedish population: Early and late implant loss. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 44s–51s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrektsson, T.; Branemark, P.I.; Hansson, H.A.; Lindstrom, J. Osseointegrated titanium implants. Requirements for ensuring a long-lasting, direct bone-to-implant anchorage in man. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1981, 52, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, M.; Hirsch, J.M.; Lekholm, U.; Thomsen, P. Biological factors contributing to failures of osseointegrated oral implants. Success criteria and epidemiology. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 1998, 106, 527–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szmukler-Moncler, S.; Salama, H.; Reingewirtz, Y.; Dubruille, J.H. Timing of loading and effect of micromotion on bone-dental implant interface: Review of experimental literature. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998, 43, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrektsson, T.; Zarb, G.; Worthington, P.; Eriksson, A.R. The long-term efficacy of currently used dental implants: A review and proposed criteria of success. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 1986, 1, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Friberg, B.; Sennerby, L.; Grondahl, K.; Bergstrom, C.; Back, T.; Lekholm, U. On cutting torque measurements during implant placement: A 3-year clinical prospective study. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 1999, 1, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilhan, H.; Geckili, O.; Mumcu, E.; Bozdag, E.; Sunbuloglu, E.; Kutay, O. Influence of surgical technique, implant shape and diameter on the primary stability in cancellous bone. J. Oral Rehabil. 2010, 37, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocchero, M.; Toia, M.; Cecchinato, D.; Becktor, J.P.; Coelho, P.G.; Jimbo, R. Biomechanical, Biologic, and Clinical Outcomes of Undersized Implant Surgical Preparation: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2016, 31, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Sullivan, D.; Sennerby, L.; Meredith, N. Measurements comparing the initial stability of five designs of dental implants: A human cadaver study. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2000, 2, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, M.; Grusovin, M.G.; Willings, M.; Coulthard, P.; Worthington, H.V. The effectiveness of immediate, early, and conventional loading of dental implants: A Cochrane systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2007, 22, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stocchero, M. On Influence of Undersized Implant Site On Implant Stability and Osseointegration; Malmö University: Malmö, Sverige, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bashutski, J.D.; D’Silva, N.J.; Wang, H.L. Implant compression necrosis: Current understanding and case report. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duyck, J.; Corpas, L.; Vermeiren, S.; Ogawa, T.; Quirynen, M.; Vandamme, K.; Jacobs, R.; Naert, I. Histological, histomorphometrical, and radiological evaluation of an experimental implant design with a high insertion torque. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2010, 21, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, J.Y.; Pereira, M.D.; Smith, A.A.; Houschyar, K.S.; Yin, X.; Mouraret, S.; Brunski, J.B.; Helms, J.A. Multiscale analyses of the bone-implant interface. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toia, M.; Stocchero, M.; Cecchinato, F.; Corra, E.; Jimbo, R.; Cecchinato, D. Clinical Considerations of Adapted Drilling Protocol by Bone Quality Perception. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2017, 32, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berglundh, T.; Armitage, G.; Araujo, M.G.; Avila-Ortiz, G.; Blanco, J.; Camargo, P.M.; Chen, S.; Cochran, D.; Derks, J.; Figuero, E.; et al. Peri-implant diseases and conditions: Consensus report of workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S286–S291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwarz, F.; John, G.; Schmucker, A.; Sahm, N.; Becker, J. Combined surgical therapy of advanced peri-implantitis evaluating two methods of surface decontamination: A 7-year follow-up observation. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, A.; Albrektsson, T.; Grane, B.; McQueen, D. Thermal injury to bone. A vital-microscopic description of heat effects. Int. J. Oral Surg. 1982, 11, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, A.R.; Albrektsson, T. Temperature threshold levels for heat-induced bone tissue injury: A vital-microscopic study in the rabbit. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1983, 50, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, G.; Zigman, T.; Davila, S.; Udilljak, T.; Staroveski, T.; Brezak, D.; Babic, S. Cortical bone drilling and thermal osteonecrosis. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon) 2012, 27, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, A.; Misic, T.; Milicic, B.; Calvo-Guirado, J.L.; Aleksic, Z.; Ethinic, A. Heat generation during implant placement in low-density bone: Effect of surgical technique, insertion torque and implant macro design. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2013, 24, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuoka, M.; Motoyoshi, M.; Sakaguchi, M.; Shinohara, A.; Shigeede, T.; Saito, Y.; Matsuda, M.; Shimizu, N. Friction heat during self-drilling of an orthodontic miniscrew. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 40, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.; Boyde, A.; Howell, P.G. A model of temperature transients in dental implants. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 2795–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglundh, T.; Stavropoulos, A. Preclinical in vivo research in implant dentistry. Consensus of the eighth European workshop on periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanoff, C.J.; Widmark, G.; Johansson, C.; Wennerberg, A. Histologic evaluation of bone response to oxidized and turned titanium micro-implants in human jawbone. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2003, 18, 341–348. [Google Scholar]

- Karl, M.; Albrektsson, T. Clinical Performance of Dental Implants with a Moderately Rough (TiUnite) Surface: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Clinical Studies. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2017, 32, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wennerberg, A.; Albrektsson, T. Effects of titanium surface topography on bone integration: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2009, 20, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennerberg, A.; Albrektsson, T. On implant surfaces: A review of current knowledge and opinions. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2010, 25, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, S.R.; James, D.F. Measurement of thermal conductivity of bovine cortical bone. Med. Eng. Phys. 2000, 22, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghvami, M.; Brunski, J.B.; Serdar Tulu, U.; Chen, C.H.; Helms, J.A. A Thermal and Biological Analysis of Bone Drilling. J. Biomech. Eng. 2018, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikenheiser, M.A.; Markel, M.D.; Lewallen, D.G.; Chao, E.Y. Thermal response and torque resistance of five cortical half-pins under simulated insertion technique. J. Orthop. Res. 1995, 13, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludewig, R. Temperaturmessungen Beim Knochensagen; University of Gissen: Gissen, Germany, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Lundskog, J. Heat and bone tissue. An experimental investigation of the thermal properties of bone and threshold levels for thermal injury. Scand. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1972, 9, 72–74. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, A.R. Heat-Induced Bone Tissue Injury: An in Vivo Investigation of Heat Tolerance of Bone Tissue and Temperature Rise in the Drilling of Cortical Bone; University of Göteborg: Gothenburg, Sweden, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gurdan, Z.; Vajta, L.; Toth, A.; Lempel, E.; Joob-Fancsaly, A.; Szalma, J. Effect of pre-drilling on intraosseous temperature during self-drilling mini-implant placement in a porcine mandible model. J. Oral Sci. 2017, 59, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flanagan, D. Heat generated during seating of dental implant fixtures. J. Oral Implantol. 2014, 40, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, R.A.; Albrektsson, T. The effect of heat on bone regeneration: An experimental study in the rabbit using the bone growth chamber. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1984, 42, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocchero, M.; Toia, M.; Jinno, Y.; Cecchinato, F.; Becktor, J.P.; Naito, Y.; Halldin, A.; Jimbo, R. Influence of different drilling preparation on cortical bone: A biomechanical, histological, and micro-CT study on sheep. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natali, A.N.; Carniel, E.L.; Pavan, P.G. Dental implants press fit phenomena: Biomechanical analysis considering bone inelastic response. Dent. Mater. 2009, 25, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, W.E. Bone tissue interface. J. Dent. Educ. 1988, 52, 804–809. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, W.E.; Garetto, L.P.; DeCastro, R.A. Remodeling of devitalized bone threatens periosteal margin integrity of endosseous titanium implants with threaded or smooth surfaces: Indications for provisional loading and axially directed occlusion. J. Indiana Dent. Assoc. 1989, 68, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, J.F. Dynamic aspects of the implant-bone-interface. In Dental implants. Materials and systems; Heimke, G., Ed.; Carl Hanser Verlag: Munchen, Germany, 1980; pp. 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Shalabi, M.M.; Wolke, J.G.; Jansen, J.A. The effects of implant surface roughness and surgical technique on implant fixation in an in vitro model. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2006, 17, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, M.V.; Elias, C.N.; Lima, C.J.H. The effects of superficial roughness and design on the primary stability of dental implants. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2011, 13, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zechner, W.; Tangl, S.; Furst, G.; Tepper, G.; Thams, U.; Mailath, G.; Watzek, G. Osseous healing characteristics of three different implant types. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2003, 14, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumer, M.; Keskiner, I.; Mercan, U.; Misir, F.; Cankaya, S. Assessment of heat generation during implant insertion. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 112, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A.I.; Richards, R.G.; Milz, S.; Schneider, E.; Pearce, S.G. Animal models for implant biomaterial research in bone: A review. Eur. Cell Mater. 2007, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drilling Protocol | Implant Surface | |

|---|---|---|

| Group A (n = 10) | Undersized | Moderately rough |

| Group B (n = 10) | Non-undersized | Moderately rough |

| Group C (n = 10) | Undersized | Turned |

| Group D (n = 10) | Non-undersized | Turned |

| Basal Temperature | Maximum Temperature | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Max | Min | Mean | SD | Max | Min | |

| Group A | 31.3 | 2.3 | 34.5 | 28.4 | 39.6 | 3.3 | 45.3 | 34.7 |

| Group B | 31.0 | 3.4 | 34.7 | 23.7 | 36.0 | 3.4 | 41.5 | 28.6 |

| Group C | 31.0 | 3.3 | 34.0 | 23.6 | 39.1 | 3.7 | 44.0 | 33.4 |

| Group D | 31.3 | 2.3 | 34.2 | 27.5 | 36.4 | 1.8 | 39.9 | 33.6 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stocchero, M.; Jinno, Y.; Toia, M.; Ahmad, M.; Papia, E.; Yamaguchi, S.; Becktor, J.P. Intraosseous Temperature Change during Installation of Dental Implants with Two Different Surfaces and Different Drilling Protocols: An In Vivo Study in Sheep. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1198. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081198

Stocchero M, Jinno Y, Toia M, Ahmad M, Papia E, Yamaguchi S, Becktor JP. Intraosseous Temperature Change during Installation of Dental Implants with Two Different Surfaces and Different Drilling Protocols: An In Vivo Study in Sheep. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8(8):1198. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081198

Chicago/Turabian StyleStocchero, Michele, Yohei Jinno, Marco Toia, Marianne Ahmad, Evaggelia Papia, Satoshi Yamaguchi, and Jonas P. Becktor. 2019. "Intraosseous Temperature Change during Installation of Dental Implants with Two Different Surfaces and Different Drilling Protocols: An In Vivo Study in Sheep" Journal of Clinical Medicine 8, no. 8: 1198. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081198

APA StyleStocchero, M., Jinno, Y., Toia, M., Ahmad, M., Papia, E., Yamaguchi, S., & Becktor, J. P. (2019). Intraosseous Temperature Change during Installation of Dental Implants with Two Different Surfaces and Different Drilling Protocols: An In Vivo Study in Sheep. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(8), 1198. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081198