Abstract

Periprocedural imaging assessment for percutaneous Left Atrial Appendage (LAA) transcatheter occlusion can be obtained by utilizing different imaging modalities including fluoroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and ultrasound imaging. Given the complex and variable morphology of the left atrial appendage, it is crucial to obtain the most accurate LAA dimensions to prevent intra-procedural device changes, recapture maneuvers, and prolonged procedure time. We therefore sought to examine the accuracy of the most commonly utilized imaging modalities in LAA occlusion. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was waived as we only reviewed published data. By utilizing PUBMED which is an integrated online website to list the published literature based on its relevance, we retrieved thirty-two articles on the accuracy of most commonly used imaging modalities for pre-procedural assessment of the left atrial appendage morphology, namely, two-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography, three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography, computed tomography, and three-dimensional printing. There is strong evidence that real-time three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography is more accurate than two-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography. Three-dimensional computed tomography has recently emerged as an imaging modality and it showed exceptional accuracy when merged with three-dimensional printing technology. However, real time three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography may be considered the preferred imaging modality as it can provide accurate measurements without requiring radiation exposure or contrast administration. We will present the most common imaging modality used for LAA assessment and will provide an algorithmic approach including preprocedural, periprocedural, intraprocedural, and postprocedural.

1. Introduction

Atrial Fibrillation (AF) is a major burden on public health, it is estimated to be the cause of ≥15% of all strokes in the United States, and >100,000–125,000 embolic strokes per year, of which >20% are fatal [1]. AF risk factors, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment are beyond the scope of this review. We will focus on the classification when patients may or may not have valvular heart disease. The distinction still an area of debate. Valvular AF is the terminology used in those patients who have heart valve disorder or a prosthetic heart valve. Nonvalvular AF is generally referred in those patients who have other etiology causing the AF. The rapid and chaotic heartbeats restrict the left atrium from pumping the blood properly, which may cause it to pool and form a clot. More than 90% of thrombi in AF is formed in the left atrial appendage (LAA) [2]. The standard treatment for AF is heart rate or rhythm control and stroke prevention. Prophylactic anticoagulation is the gold standard to prevent embolic strokes in AF patients with CHADS-VASC score greater than or equal to two. For many years there has been no alternative treatment available to prevent strokes in AF patients who have high risk of bleeding and only 50–60% are therapeutically anticoagulated which make the effective long-term anticoagulation very challenging [3].

In 2001 a successful percutaneous implantation of a device to occlude the LAA cavity was done in a patient with non-valvular AF to prevent embolism [4]. Interventional closure of the LAA employing the Watchman device (Boston Scientific) was shown to be non-inferior to Oral anticoagulation (OAC) in randomized trials and has since been approved in the United States and Europe [5]. The LAA exhibits complex anatomy that commonly varies morphologically among different individuals. Post-mortem analysis of 100 left atrial appendages has demonstrated significant variability in appendage shape, dimensions, and the number of lobes presents [6]. Therefore, accurate visualization of the LAA and appreciation of its morphological considerations is an essential step in occlusion procedures. Specifically, accurately measuring the dimensions of the LAA ostium, landing zone, and maximum length of the main anchoring lobe is necessary for selecting an adequately sized occlusion device successful device placement [4]. Choosing a device that is too small increases the risk of device instability and peri-device leakage, whereas selecting a device that is too large increases the risk of LAA perforation and cardiac tamponade [7,8]. Additionally, improper device selection can result in intra-procedural device changes and recapture maneuvers and increasing length of the procedure [9].

We present a review on the most commonly used imaging modality for pre-procedural planning and assessment of the LAA morphology, which include 2D Transesophageal echocardiography (2D TEE), 3D Transesophageal echocardiography (3D TEE), Computed tomography (CT), and 3D Printing (3DP).

1.1. 3D TEE Modality Is Superior to 2D TEE

2D TEE has been the most commonly used imaging modality for pre-procedural planning. However, three-dimensional multiplanar transesophageal electrocardiography is a more accurate alternative to 2D TEE in the assessment of the LAA morphology. Advantages of 3D TEE vs. 2D TEE are illustrated in (Table 1), and comparative studies using 3D TEE are illustrated in (Table 2).

Table 1.

Advantages of 3D TEE vs. 2D TEE.

Table 2.

Literature review summary table for 3D TEE vs. 2D TEE in the preprocedural assessment of the left atrial appendage.

Zhou et al. found 3D TEE to be more accurate than 2D TEE for measuring the LAA Landing zone, LAA depth, and LAA ostial dimensions, LAA morphology after the occlusion device deployment, and visualizing any residual shunts around the entire device in one more view. In the Zhou et al. study, a residual shunt of less than 1mm was identified in three cases by 3D TEE and only once by 2D TEE [7]. Salzman et al. determined that area-derived diameter (ADD) and perimeter-derived diameter (PDD) measurements obtained via 3D TEE correlated well with the occlusion device size chosen in the procedure. Furthermore, the 3D landing zone measurements demonstrated a higher reproducibility relative to 2D TEE [8].

Yosefi et al. found that RT3DTEE provides more accurate measurements of the maximal LAA orifice than 2D TEE. 2D TEE significantly undersized the diameter of the LAA orifice relative to RT3DTEE, when compared to CT [10]. Nucifora et al. found that RT3DTEE is in more significant agreement with the dimensions obtained from CT as demonstrated by smaller bias and narrower limits of agreement with CT. Therefore, these authors believe that RT3DTEE may be the preferred imaging modality to assess LAA dimensions as it can provide accurate measurements of the LAA without requiring radiation exposure or contrast administration [11].

The real-time 3DTEE method is a feasible, fast way to assess the LAA number of lobes, the area of the orifice, maximal LAA diameter, minimum LAA diameter, and LAA depth with similar accuracy to RT3DTEE and CT according to a study published by Yosefy et al. Real-time 3DTEE consists of converting a 3DTEE image into three 2D planes (X,Y,Z), at which time a 360 degree rotational in the sagittal plane creates a single “stop shop” image that displays all aspects of the LAA morphology including number of lobes, orifice area, and maximal and minimal diameter [12]. Nakajima et al. determined that 3D TEE could accurately visualize LAA morphological variations. They studied 55 patients in normal sinus rhythm and 52 patients with atrial fibrillation. 3D TEE provides adequate 3D full volume images of all patients in NSR, whereas sufficient images were obtained in 94.6% of patients with AF using zoom mode. Excellent correlation was found between full volume mode and zoom mode [13].

1.2. CT Is More Accurate Than TEE

CT has been considered the gold standard for visualizing the LAA for its ability to acquire 3D volumetric data of the LAA at various points in the cardiac cycle [4]. However, it has only recently emerged as an imaging modality for sizing the LAA before occlusion and for post-procedural evaluation of residual peri-device shunts. Although TEE remains the most commonly used imaging modality for sizing the LAA, CT may be the most accurate imaging modality. Yosefy et al. compared 2D TEE to CT and found 2D TEE to be non-inferior to CT for determining LAA area and volume. Additionally, Yosefy et al. found that of 30 patients who underwent routine TEE examination and CT in the workup of PE, RT3DTEE was found to yield measurements not significantly different than CT for the number of LAA lobes, LAA depth, LAA internal area, and LAA maximal and minimal diameter. They concluded that 3DTEE might be more practical for sizing the LAA due to its accuracy, lack of radiation, and bedside capabilities [10]. In contrast, other studies have demonstrated that measurements obtained via TEE and CT are not interchangeable and may result in clinically significant consequences. One such study by Sievert et al. showed that LAA sizing by 2D TEE alone might result in the selection of a closure device that is undersized by 20–40% [2]. Advantages of CT are illustrated in (Table 3), and comparative studies using CT are illustrated in (Table 4).

Table 3.

Advantages of CT when assessing the left atrial appendage.

Table 4.

Literature review summary table of CT imaging in the preprocedural assessment of the left atrial appendage.

MSCT is a more accurate tool in selecting proper LAA closure device size than the conventionally used TEE according to the study by Chow et al. [14] 2D-TEE measurements of orifice size are not interchangeable with those obtained via CT according to a study by Rawjani et al. The researchers concluded that due to the irregular and eccentric nature of the LAA orifice, obtaining mean orifice diameter measurements may be more accurate than planar maximal diameters for sizing circular occluder devices [15].

In the study by Wang et al. patients who underwent advanced CT imaging at this site required 1.245 devices per implantation attempt with 100% success rate, compared to patients in the first half of the PROTECT AF study who averaged 1.8 devices used per implantation attempt with an 82% success rate. Accurate sizing of the LAA landing zone is critical in successful implantation of the WATCHMAN, and this study suggests high-resolution volumetric imaging with CT should be preferred over TEE [9].

Budge et al. determined that measurements obtained via CTsb, CTp, and TEE are not interchangeable. CTsb was found to yield larger mean orifice diameters than both TEE and CTp, which produced similar mean orifice diameters. It was speculated that this was due to foreshortening associated with 2D modalities. Furthermore, when compared to TEE, both CT modalities yielded larger ostial measurements for small LAA orifices and smaller ostial measurements for larger LAA orifices within this cohort [16].

1.3. The Use of 3D Printing Can Facilitate LAA Occlusion

As more LAA occlusion procedures have been conducted, physicians have recognized the unique and diverse morphology of the LAA [17]. This anatomical intricacy may be deceptively portrayed in standardized diagnostic modalities such as 2D and 3D transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), which are the conventional pre-procedural image technique. 3D CT characterization may provide exceptional accuracy when merged with 3D printing technology. By creating a model customized to each patient’s anatomy, a physical Watchman device (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) can be implanted ex vivo so that spatial navigation and geographic accuracy of the left atrium may be established before the cardiac catheterization procedure commences. The following findings show this modality technology applied and successively replicated. They also suggest 3D CT as the best imaging technique when establishing device size. Hell et al. [18] and Li et al. [19] supported the use of 3D printing while, Goiten et al. did not support it [20] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Literature review summary table of CT 3D printing in the preprocedural assessment of the left atrial appendage.

Hell et al. and Li et al. in prospective studies both found that 3D printing of LAA was a feasible mechanism of predicting correct Watchman devices. In the study conducted by Hell et al. Mean LAA ostium diameter based on TEE was 22 ± 4 mm and based on CT 25 ± 3 mm (p = 0.014) [18]. Similarly, Li et al. performed successful Watchman implantation in 21 patients based on 3D model printing (3DP). In this study, although all patients in both groups underwent successful device implantation, significant differences did occur. After the occlusion, TOE showed that three patients in the control group had mild residual shunting (two patients with a 2 mm residual shunt, one patient with a 4 mm residual shunt). No residual shunt was observed in the 3DP group. The procedure times, contrast agent volumes, and costs were 96.4 ± 12.5 vs. 101.2 ± 13.6 min, 22.6 ± 3.0 vs. 26.9 ± 6.2 mL, and 12,676.1 vs. 12,088.6 USD for the 3DP and control groups, respectively. Compared with the control group, the radiographic exposure was significantly reduced in the 3DP group (561.4 ± 25.3 vs. 651.6 ± 32.1 mGy, p = 0.05) [19].

Goiten et al. found that LAA printed 3D models were accurate for prediction of LAA device size for the Amulet device but not for the Watchman device. Two procedures were aborted due to mismatch between LAA and any Watchman device dimensions in which all three interventional cardiology physicians that were involved in the study predicted the failures using the printed 3D model. Although 3D prints were found to be more accurate for Amulet compared to Watchman, strong agreement among physicians was demonstrated for both devices (average intra-class correlation of 0.915 for Amulet and 0.816 for Watchman) [20].

2. Algorithmic Approach for the WATCHMAN Procedural

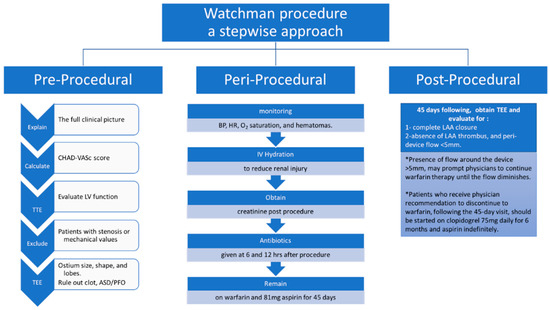

Here, we will provide an algorithmic approach including preprocedural, periprocedural, intraprocedural, and postprocedural. (Figure 1 and Figure 2) [21].

Figure 1.

A stepwise approach for pre-, peri-, and post-procedure for the successful implantation of WATCHMAN device.

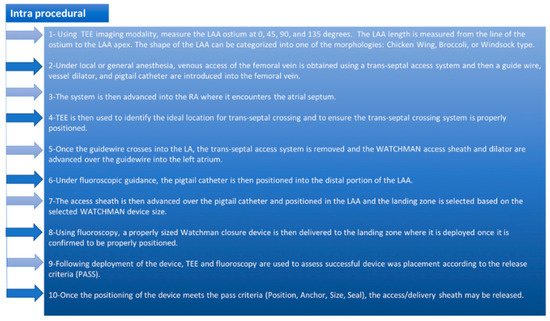

Figure 2.

The WATCHMAN implant intra-procedural steps.

3. Pre-Procedural Assessment of the LAA

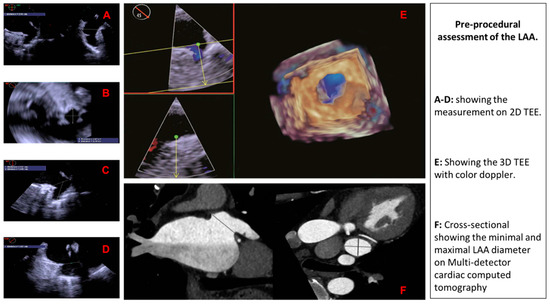

Here, we will provide the pre-procedural assessment of the LAA on 2D TEE, 3D TEE, and MDCT (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pre-procedural assessment of the LAA using different imaging modalities.

4. Conclusions

Rotational three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography is a more accurate alternative to two-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography in the assessment of the left atrial appendage morphology and has been the most commonly used imaging modality for sizing the left atrial appendage. Three-dimensional computed tomography has recently emerged as an imaging modality and it has showed exceptional accuracy when merged with three-dimensional printing technology. However, real-time three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography may be considered the preferred imaging modality to assess left atrial appendage dimensions as it can provide accurate measurements without requiring radiation exposure or contrast administration (Table 6).

Table 6.

Preprocedural imaging impact on predicting the correct size of the WATCHMAN device.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed extensively to the work presented in this literature review. R.M. (Ramez Morcos) did the literature search, created the tables & the figures, and drafted the manuscript. H.T. & P.B. drafted the manuscript and provided revision. J.C., R.M. (Rupesh Manam) & V.P. drafted the manuscript. A.C., M.K. & A.M. collected the data, drafted the manuscript, and provided revisions. B.M. reviewed the manuscript and provided critical Revision.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reiffel, J.A. Atrial fibrillation and stroke: Epidemiology. Am. J. Med. 2014, 127, e15–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sievert, H.; Lesh, M.D.; Trepels, T.; Omran, H.; Bartorelli, A.; Della Bella, P.; Nakai, T.; Reisman, M.; DiMario, C.; Block, P.; et al. Percutaneous left atrial appendage transcatheter occlusion to prevent stroke in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation: Early clinical experience. Circulation 2002, 105, 1887–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Go, A.S.; Hylek, E.M.; Borowsky, L.H.; Phillips, K.A.; Selby, J.V.; Singer, D.E. Warfarin use among ambulatory patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: The anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 131, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wunderlich, N.C.; Beigel, R.; Swaans, M.J.; Ho, S.Y.; Siegel, R.J. Percutaneous interventions for left atrial appendage exclusion: Options, assessment, and imaging using 2D and 3D echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 8, 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, D.R.; Reddy, V.Y.; Turi, Z.G.; Doshi, S.K.; Sievert, H.; Buchbinder, M.; Mulli, M.; Sick, P. Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage versus warfarin therapy for prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: A randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2009, 374, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, R.; Kosiński, A.; Brala, M.; Piwko, G.; Lewicka, E.; Dąbrowska-Kugacka, A.; Raczak, G.; Kozłowski, D.; Grzybiak, M. Variability of the Left Atrial Appendage in Human Hearts. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Song, H.; Zhang, L.; Deng, Q.; Chen, J.; Hu, B.; Wang, Y.; Guo, R. Roles of real-time three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography in peri-operation of transcatheter left atrial appendage closure. Medicine 2017, 96, e5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Salzmann, M.; Meincke, F.; Kreidel, F.; Spangenberg, T.; Ghanem, A.; Kuck, K.H.; Bergmann, M.W. Improved Algorithm for Ostium Size Assessment in Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Using Three-Dimensional Echocardiography. J. Invasive Cardiol. 2017, 29, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.D.; Eng, M.; Kupsky, D.; Myers, E.; Forbes, M.; Rahman, M.; Zaidan, M.; Parikh, S.; Wyman, J.; Pantelic, M.; et al. Application of 3-Dimensional Computed Tomographic Image Guidance to WATCHMAN Implantation and Impact on Early Operator Learning Curve: Single-Center Experience. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016, 9, 2329–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosefy, C.; Laish-Farkash, A.; Azhibekov, Y.; Khalameizer, V.; Brodkin, B.; Katz, A. A New Method for Direct Three-Dimensional Measurement of Left Atrial Appendage Dimensions during Transesophageal Echocardiography. Echocardiography 2016, 33, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucifora, G.; Faletra, F.F.; Regoli, F.; Pasotti, E.; Pedrazzini, G.; Moccetti, T.; Auricchio, A. Evaluation of the left atrial appendage with real-time 3-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography: Implications for catheter-based left atrial appendage closure. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2011, 4, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosefy, C.; Azhibekov, Y.; Brodkin, B.; Khalameizer, V.; Katz, A.; Laish-Farkash, A. Rotational method simplifies 3-dimensional measurement of left atrial appendage dimensions during transesophageal echocardiography. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2016, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, H.; Seo, Y.; Ishizu, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Machino, T.; Harimura, Y.; RyoKawamura, R.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Tada, H.; Aonuma, K. Analysis of the left atrial appendage by three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography. Am. J. Cardiol. 2010, 106, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, D.H.; Bieliauskas, G.; Sawaya, F.J.; Millan-Iturbe, O.; Kofoed, K.F.; Søndergaard, L.; De Backer, O. A comparative study of different imaging modalities for successful percutaneous left atrial appendage closure. Open Heart 2017, 4, e000627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajwani, A.; Nelson, A.J.; Shirazi, M.G.; Disney, P.J.; Teo, K.S.; Wong, D.T.; Young, G.D.; Worthley, S.G. CT sizing for left atrial appendage closure is associated with favourable outcomes for procedural safety. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 18, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budge, L.P.; Shaffer, K.M.; Moorman, J.R.; Lake, D.E.; Ferguson, J.D.; Mangrum, J.M. Analysis of in vivo left atrial appendage morphology in patients with atrial fibrillation: A direct comparison of transesophageal echocardiography, planar cardiac CT, and segmented three-dimensional cardiac CT. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2008, 23, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.A.N.; Di Biase, L.; Horton, R.P.; Nguyen, T.; Morhanty, P.; Natale, A. Left atrial appendage studied by computed tomography to help planning for appendage closure device placement. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2010, 21, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hell, M.M.; Achenbach, S.; Yoo, I.S.; Franke, J.; Blachutzik, F.; Roether, J.; Graf, V.; Raaz-Schrauder, D.; Marwan, D.; Schlundt, C. 3D printing for sizing left atrial appendage closure device: Head-to-head comparison with computed tomography and transoesophageal echocardiography. EuroIntervention 2017, 13, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Shu, M.; Wang, X.; Song, Z. Application of 3D printing technology to left atrial appendage occlusion. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 231, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goitein, O.; Fink, N.; Guetta, V.; Beinart, R.; Brodov, Y.; Konen, E.; Goitein, D.; Di Segni, E.; Grupper, A.; Glikson, M. Printed MDCT 3D models for prediction of left atrial appendage (LAA) occluder device size: A feasibility study. EuroIntervention 2017, 13, e1076–e1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möbius-Winkler, S.; Sandri, M.; Mangner, N.; Lurz, P.; Dähnert, I.; Schuler, G. The WATCHMAN left atrial appendage closure device for atrial fibrillation. J. Vis. Exp. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).