Hybrid Breast Reconstruction Revisited: Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Fat Grafting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Surgical Procedure

2.2. Evaluation of the Results

- Satisfaction with Breasts, which grades the patients comfort with the appearance, symmetry, and general results of the breasts after being operated.

- Quality of Life, including subjects such as psychosocial, physical and sexual well-being, assessing the impact breast surgery has on patients’ lives.

- Satisfaction with Care—satisfaction with the medical care which was received, including communication skills with not only the surgeon, but also the medical team, and postoperative care.

- Physical Well-Being, which refers to symptoms and physical discomfort that patients might experience postoperatively.

| Question | Content | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Satisfaction with breast appearance | Aesthetic outcomes |

| Q2 | Psychosocial well-being | Aesthetic outcomes |

| Q4 | Sexual well-being | Aesthetic outcomes |

| Q5 | Satisfaction with surgical outcome | Aesthetic outcomes Functional/medical outcome |

| Q9 | Body image and self-confidence | Aesthetic outcomes |

| Q3 | Physical symptoms and discomfort | Functional/medical outcomes |

| Q6 | Pain or discomfort in the chest | Functional/medical outcomes |

| Q7 | Difficulty with arm movement or daily activities | Functional/medical outcomes |

| Q8 | Visibility and palpability of implant rippling | Functional/medical outcomes Aesthetic outcomes |

| Q10 | Perception of breast sensation | Functional/medical outcomes |

| Q11 | Psychological meaning of the surgery | Functional/medical outcomes |

| Q12 | Preoperative fear about cosmetic result | Functional/medical outcomes Aesthetic outcomes |

| Q13 | Information received from the surgeon | Satisfaction with care |

| Q14 | Communication and support from the medical team | Satisfaction with care |

| Q15 | Availability and responsiveness of the team | Satisfaction with care |

| Q16 | Overall satisfaction with medical care | Satisfaction with care |

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

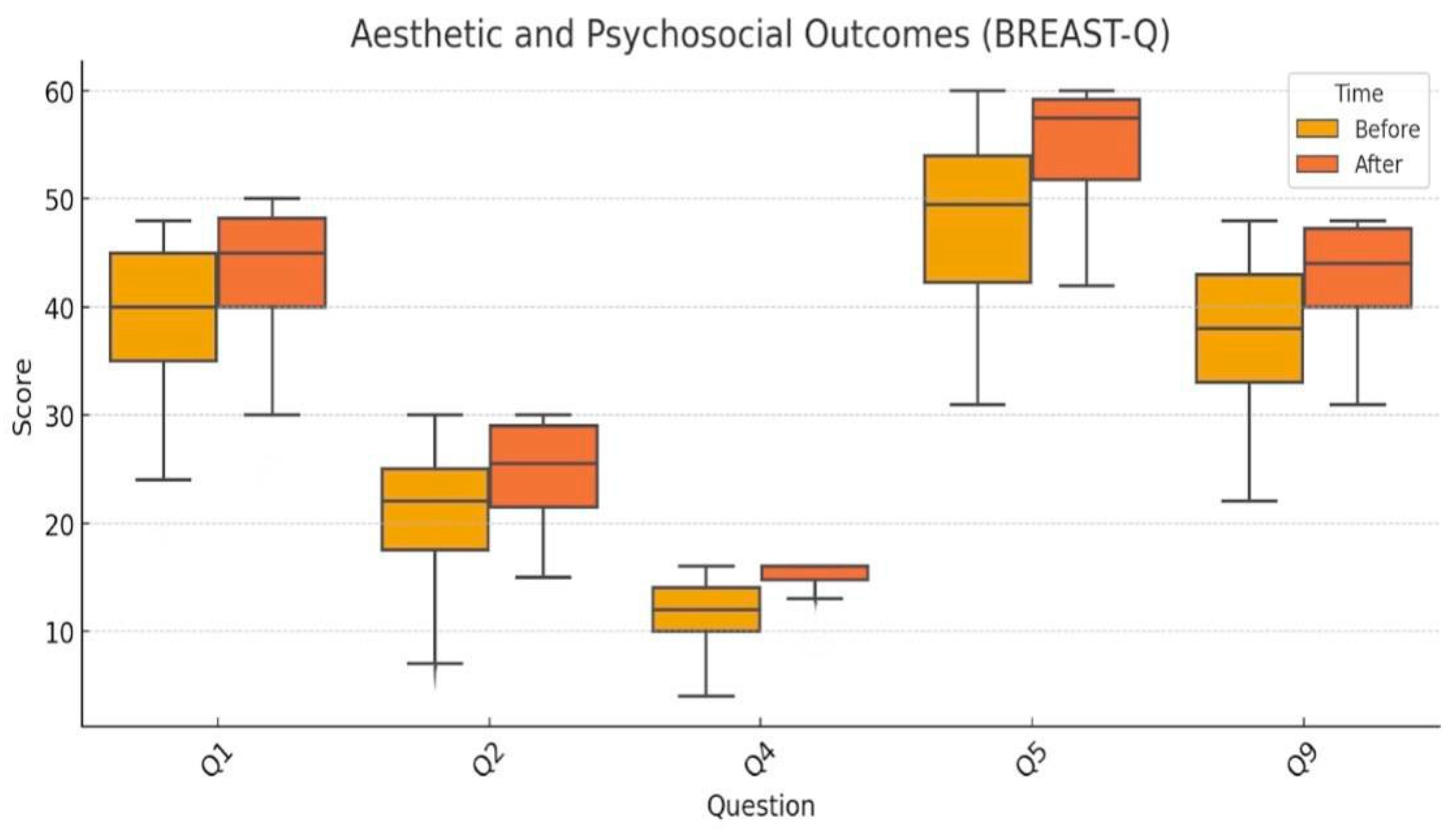

3.1. Aesthetic and Psychosocial Outcomes

- Q1 (Satisfaction with breast appearance): Analyzed using the paired t-test (p < 0.001), with a mean increase from 39.5 to 43.9.

- Q2 (Psychosocial well-being): Non-normally distributed, analyzed using the Wilcoxon test (p < 0.001), with improvement from 20.6 to 25.0.

- Q4 (Sexual well-being): Evaluated using the Wilcoxon test (p < 0.001); scores rose from 12.0 to 14.8.

- Q5 (Overall satisfaction with reconstructive outcome): t-test applied (p < 0.001); scores improved significantly from 47.5 to 54.8.

- Q9 (Body image and self-confidence): Wilcoxon test (p < 0.001), with a mean increase from 38.2 to 42.8.

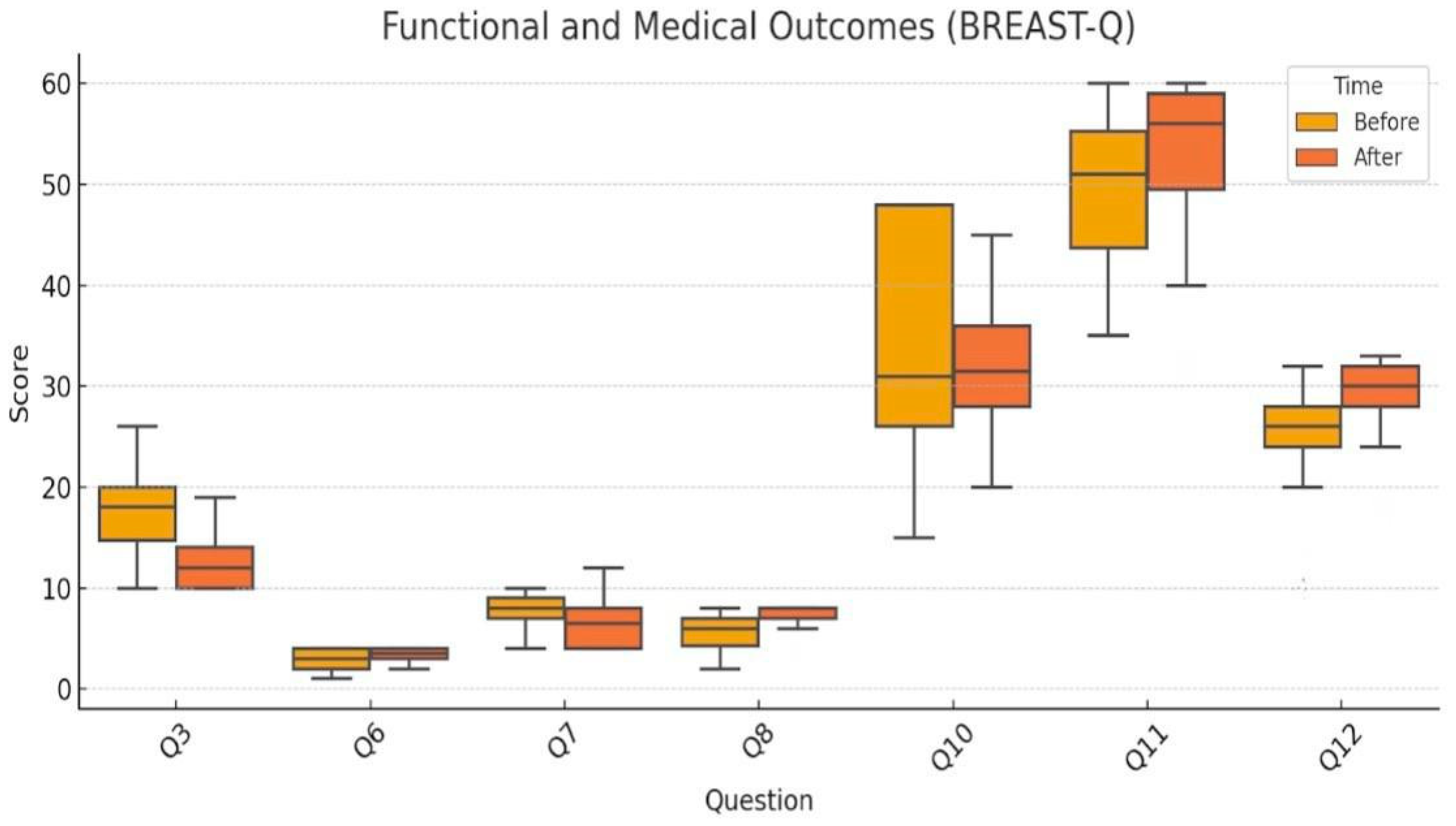

3.2. Functional and Physical Outcomes

- Q3 (Physical symptoms/discomfort): Significant reduction from 17.6 to 12.6, analyzed using the Wilcoxon test (p < 0.001).

- Q6 (Pain): Modest improvement assessed via Wilcoxon test (p < 0.001).

- Q7 (Physical limitations): Also evaluated with Wilcoxon test (p = 0.01), showing a small but statistically significant improvement.

- Q10 (Breast sensation): Analyzed using the paired t-test, showing a nonsignificant decrease (p = 0.15), indicating preserved sensory function.

- Q8 (Rippling visibility): Evaluated only postoperatively, not subject to paired testing; mean score was 7.4, indicating acceptable aesthetic outcomes.

3.3. Satisfaction with Medical Care

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of the Main Results

4.2. Comparison with the Existing Literature

4.3. Limitations of the Current Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gabriel, A.; Nahabedian, M.Y.; Maxwell, G.P.; Storm, T. (Eds.) Spear’s Surgery of the Breast: Principles and Art, 4th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, A.; Abu-Ghname, A.; Davis, M.J.; Winocour, S.J.; Hanson, S.E.; Chu, C.K. Fat Grafting in Breast Reconstruction. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2020, 34, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.A.; Martin, S.A.; Cheesborough, J.E.; Lee, G.K.; Nazerali, R.S. The safety and efficacy of autologous fat grafting during second stage breast reconstruction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2021, 74, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzouk, K.; Humbert, P.; Borens, B.; Gozzi, M.; Al Khori, N.; Pasquier, J.; Tabrizi, A.R. Skin trophicity improvement by mechanotherapy for lipofilling- based breast reconstruction postradiation therapy. Breast J. 2020, 26, 725–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra-Renom, J.M.; Muñoz-Olmo, J.L.; Serra-Mestre, J.M. Fat grafting in postmastectomy breast reconstruction with expanders and prostheses in patients who have received radiotherapy: Formation of new subcutaneous tissue. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 125, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommeling, C.; Van Landuyt, K.; Depypere, H.; Broecke, R.V.D.; Monstrey, S.; Blondeel, P.; Morrison, W.; Stillaert, F. Composite breast reconstruction: Implant- based breast reconstruction with adjunctive lipofilling. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2017, 70, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribuffo, D.; Atzeni, M.; Guerra, M.; Bucher, S.; Politi, C.; Deidda, M.; Atzori, F.; Dessi, M.; Madeddu, C.; Lay, G. Treatment of irradiated expanders: Protective lipofilling allows immediate prosthetic breast reconstruction in the setting of postoperative radiotherapy. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2013, 37, 1146–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, S.; Zingaretti, N.; De Francesco, F.; Riccio, M.; De Biasio, F.; Massarut, S.; Almesberger, D.; Parodi, P.C. Long-term impact of lipofilling in hybrid breast reconstruction: Retrospective analysis of two cohorts. Eur. J. Plast. Surg. 2020, 43, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillaert, F.B. The prepectoral, hybrid breast reconstruction: The synergy of lipofilling and breast implants. In Plastic and Aesthetic Regenerative Surgery and Fat Grafting: Clinical Application and Operative Techniques; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1181–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Albornoz, C.R.; Bach, P.B.; Mehrara, B.J.; Disa, J.J.; Pusic, A.L.; McCarthy, C.M.; Colleen, M.M.D.; Evan, M.D.; Peter, G.M.D. A paradigm shift in US breast reconstruction: Increasing implant rates. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 131, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delay, E.; Garson, S.; Tousson, G.; Sinna, R. Fat injection to the breast: Technique, results, and indications based on 880 procedures over 10 years. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2009, 29, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quoc, C.H.; Dias, L.P.N.; Braghiroli, O.F.M.; Martella, N.; Giovinazzo, V.; Piat, J.M. Oncological safety of lipofilling in healthy BRCA carriers after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy: A case series. Eur. J. Breast Health 2019, 15, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q-Portfolio. BREAST-Q [Internet]. Available online: https://qportfolio.org/breast-q/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Chen, J.; Alghamdi, A.A.; Wong, C.Y.; Alnaim, M.F.; Kuper, G.; Zhang, J. The Efficacy of Fat Grafting on Treating Post-Mastectomy Pain with and without Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 4, 2057–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, Y.; Li, G. Safety and Effectiveness of Autologous Fat Grafting after Breast Radiotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 147, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tukiama, R.; Vieira, R.A.C.; Moura, E.C.R.; Oliveira, A.G.C.; Facina, G.; Zucca-Matthes, G.; Neto, J.N.; de Oliveira, C.M.B.; Leal, P.D.C. Oncologic safety of breast reconstruction with autologous fat grafting: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 48, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Qurashi, A.A.; Shah Mardan, Q.N.M.; Alzahrani, I.A.; AlAlwan, A.Q.; Bafail, A.; Alaa Adeen, A.M.; Albahrani, A.; Aledwani, B.N.; Halawani, I.R.; AlBattal, N.Z.; et al. Efficacy of Exclusive Fat Grafting for Breast Reconstruction: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2024, 48, 4979–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Shi, Y.; Li, Q.; Guo, X.; Han, X.; Li, F. Oncological Safety of Autologous Fat Grafting in Breast Reconstruction: A Meta-analysis Based on Matched Cohort Studies. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2022, 46, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojallal, A.; Lequeux, C.; Shipkov, C.; Breton, P.; Foyatier, J.L.; Braye, F.; Damour, O. Improvement of skin quality after fat grafting: Clinical observation and an animal study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009, 124, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigotti, G.; Marchi, A.; Stringhini, P.; Baroni, G.; Galiè, M.; Molino, A.M.; Mercanti, A.; Micciolo, R.; Sbarbati, A. Determining the oncological risk of autologous lipoaspirate grafting for post-mastectomy breast reconstruction. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2010, 34, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaaban, A.; Anwar, M.; Ramadan, R. The role of platelet rich plasma enriched fat graft for correction of deformities after conservative breast surgery. Breast Dis. 2024, 43, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Samadi, P.; Sheykhhasan, M.; Khoshinani, H.M. The Use of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Aesthetic and Regenerative Medicine: A Comprehensive Review. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2019, 43, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigli, S.; Amabile, M.I.; DIPastena, F.; DELuca, A.; Gulia, C.; Manganaro, L.; Monti, M.; Ballesio, L. Lipofilling Outcomes Mimicking Breast Cancer Recurrence: Case Report and Update of the Literature. Anticancer Res. 2017, 37, 5395–5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osswald, R.; Boss, A.; Lindenblatt, N.; Vorburger, D.; Dedes, K. Does lipofilling after oncologic breast surgery increase the amount of suspicious imaging and required biopsies?—A systematic meta-analysis. Breast J. 2020, 26, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinell-White, X.A.; Etra, J.; Newell, M.; Tuscano, D.; Shin, K.; Losken, A. Radiographic Implications of Fat Grafting to the Reconstructed Breast. Breast J. 2015, 21, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantini, M.; Cipriani, A.; Belli, P.; Bufi, E.; Fubelli, R.; Visconti, G.; Salgarello, M.; Bonomo, L. Radiological findings in mammary autologous fat injections: A multi-technique evaluation. Clin. Radiol. 2013, 68, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condé-Green, A.; Kotamarti, V.; Nini, K.T.; Wey, P.D.; Ahuja, N.K.; Granick, M.S.; Lee, E.S. Fat Grafting for Gluteal Augmentation: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Meta-Analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 138, 437e–446e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntean, M.V.; Pop, I.C.; Ilies, R.A.; Pelleter, A.; Vlad, I.C.; Achimas-Cadariu, P. Exploring the Role of Autologous Fat Grafting in Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review of Complications and Aesthetic Results. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Question | Mean Before | Mean After | Difference | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 39.0 | 43.69 | 4.69 | <0.01 |

| Q2 | 20.56 | 25.03 | 4.47 | <0.01 |

| Q3 | 17.59 | 12.56 | −5.03 | <0.01 |

| Q4 | 12.0 | 14.84 | 2.84 | <0.01 |

| Q5 | 47.47 | 54.75 | 7.28 | <0.01 |

| Q6 | 2.84 | 3.38 | 0.54 | <0.01 |

| Q7 | 7.47 | 6.62 | −0.85 | 0.01 |

| Q8 | - | 7.37 | - | - |

| Q9 | 38.19 | 42.84 | 4.65 | <0.01 |

| Q10 | 34.97 | 32.12 | −2.85 | 0.15 |

| Q11 | 49.41 | 53.12 | 3.71 | <0.01 |

| Q12 | 25.47 | 29.12 | 3.65 | <0.01 |

| Q13 | 11.35 | 9.18 | −2.17 | <0.01 |

| Q14 | 54.34 | 57.62 | 3.28 | <0.01 |

| Q15 | 46.9 | 47.74 | 0.84 | 0.03 |

| Q16 | 27.84 | 27.97 | 0.13 | 0.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pop, I.C.; Muntean, M.V.; Gata, V.A.; Ilies, R.A.; Nicoara, D.; Filip, C.I.; Pop, V.; Achimas-Cadariu, P.A. Hybrid Breast Reconstruction Revisited: Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Fat Grafting. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031158

Pop IC, Muntean MV, Gata VA, Ilies RA, Nicoara D, Filip CI, Pop V, Achimas-Cadariu PA. Hybrid Breast Reconstruction Revisited: Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Fat Grafting. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031158

Chicago/Turabian StylePop, Ioan Constantin, Maximilian Vlad Muntean, Vlad Alexandru Gata, Radu Alexandru Ilies, Delia Nicoara, Claudiu Ioan Filip, Vasile Pop, and Patriciu Andrei Achimas-Cadariu. 2026. "Hybrid Breast Reconstruction Revisited: Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Fat Grafting" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031158

APA StylePop, I. C., Muntean, M. V., Gata, V. A., Ilies, R. A., Nicoara, D., Filip, C. I., Pop, V., & Achimas-Cadariu, P. A. (2026). Hybrid Breast Reconstruction Revisited: Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Fat Grafting. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031158