Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma Imitating Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Rare and Complex Diagnostic Challenge

Abstract

1. Introduction

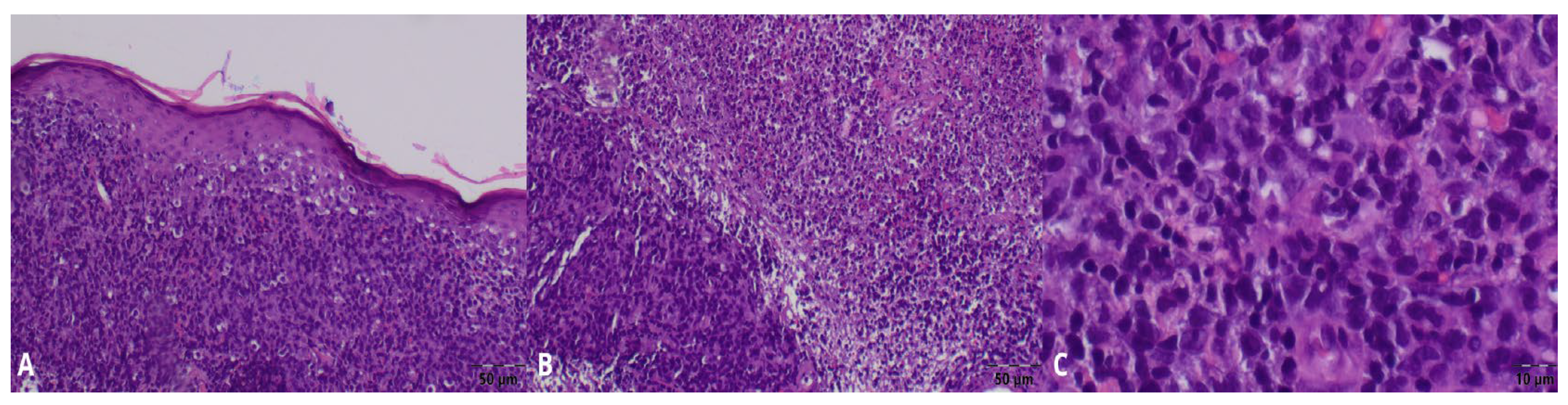

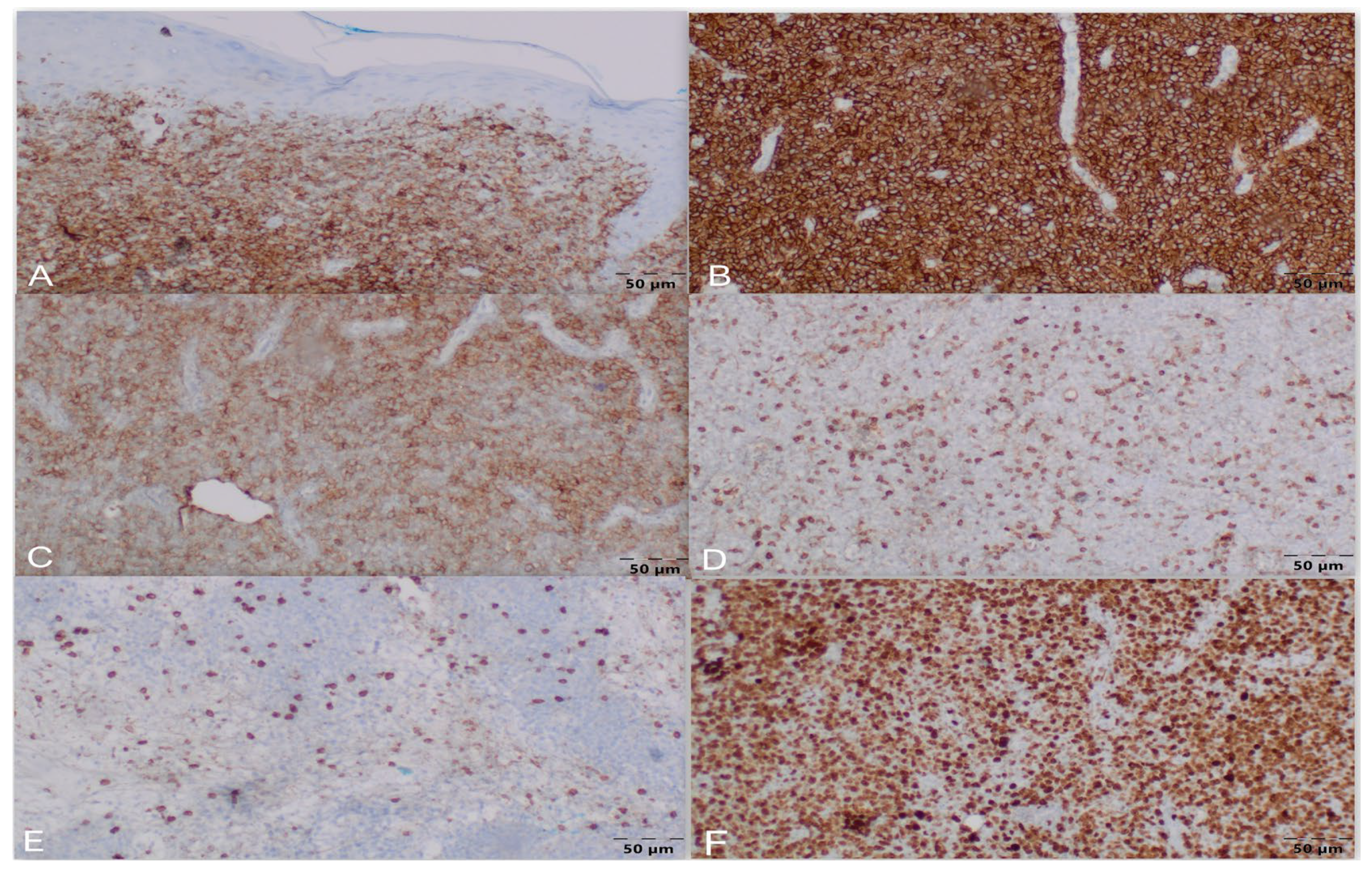

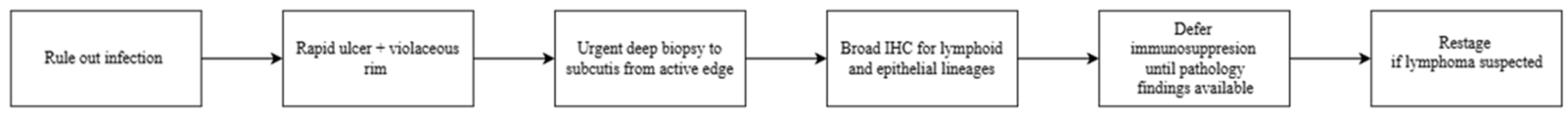

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PG | Pyoderma Gangrenosum |

| CBCL | Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma |

| DLBCL | Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma |

| A-DLBCL | Anaplastic Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma |

| PCDLBCL-LT | Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma–Leg Type |

| PCFCL | Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma |

| DLBCL-NOS | Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma–Not Otherwise Specified |

References

- Chen, B.; Li, W.; Qu, B. Practical aspects of the diagnosis and management of pyoderma gangrenosum. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1134939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, M.J.; Ye, J.M. Pyoderma gangrenosum: A review of clinical features and outcomes of 23 cases requiring inpatient management. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2014, 2014, 461467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.L.; Badawi, A.H.; Thornton, C.; Ortega-Loayza, A.G. Clinical mimickers misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2025, 26, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.C.; Vivas, A.; Rey, A.; Kirsner, R.S.; Romanelli, P. Atypical ulcers: Wound biopsy results from a university wound pathology service. Ostomy/Wound Manag. 2012, 58, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam, V.K.; Schilling, A.; Germinario, A.; Mete, M.; Kim, P.; Steinberg, J.; Attinger, C.E. Prevalence of immune disease in patients with wounds presenting to a tertiary wound healing centre. Int. Wound J. 2012, 9, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, P.; Sica, A.; Ronchi, A.; Caccavale, S.; Franco, R.; Argenziano, G. Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas: An Update. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma: Overview, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1099540-overview (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Willemze, R.; Cerroni, L.; Kempf, W.; Berti, E.; Facchetti, F.; Swerdlow, S.H.; Jaffe, E.S. The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Blood 2019, 133, 1703–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Sood, R.; Agrawal, N.; Pasricha, S.; Mehta, A. Anaplastic Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma: A Single Center Experience. Indian J. Hematol. Blood Transfus. 2019, 35, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, A.; Kohno, K.; Kuroda, N.; Yorita, K.; Megahed, N.A.; Eladl, A.E.; Daroontum, T.; Ishikawa, E.; Suzuki, Y.; Shimada, S.; et al. Anaplastic variant of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with hallmark cell appearance: Two cases highlighting a broad diversity in the diagnostics. Pathol. Int. 2018, 68, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, H.; Imai, Y.; Ota, S.; Yamamoto, G.; Takahashi, T.; Fukayama, M.; Kurokawa, M. CD30-positive anaplastic variant diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A rare case presented with cutaneous involvement. Int. J. Hematol. 2010, 92, 550–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokołowska-Wojdyło, M.; Maj, J.; Robak, E.; Placek, W.; Wojas-Pelc, A.; Jankowska-Konsur, A.; Olek-Hrab, K.; Gniadecki, R.; Rudnicka, L. Primary cutaneous lymphomas—Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines of the Polish Dermatological Society. Dermatol. Rev./Przegl. Dermatol. 2017, 104, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, A.; Vitiello, P.; Caccavale, S.; Sagnelli, C.; Calogero, A.; Doraro, C.A.; Pastore, F.; Ciardiello, F.; Argenziano, G.; Reginelli, A.; et al. Primary Cutaneous DLBCL Non-GCB Type: Challenges of a Rare Case. Open Med. (Wars) 2020, 15, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oguz, O.; Engin, B.; Demirkesen, C. Primary cutaneous CD30-positive large B-cell lymphoma associated with Epstein-Barr virus. Int. J. Dermatol. 2003, 42, 718–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Chen, Q.; Xiao, H.; Liu, F.; Qi, C.; Yu, Z.; Li, X.; et al. Anaplastic Variant of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma Displays Intricate Genetic Alterations and Distinct Biological Features. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2017, 41, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmachi, K. JSH practical guidelines for hematological malignancies, 2023: II. Lymphoma5. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (DLBCL, NOS). Int. J. Hematol. 2025, 122, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrade, F.; Jardin, F.; Thieblemont, C.; Thyss, A.; Emile, J.F.; Castaigne, S.; Coiffier, B.; Haioun, C.; Bologna, S.; Fitoussi, O.; et al. Attenuated immunochemotherapy regimen (R-miniCHOP) in elderly patients older than 80 years with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounier, N.; El Gnaoui, T.; Tilly, H.; Canioni, D.; Sebban, C.; Casasnovas, R.O.; Delarue, R.; Sonet, A.; Beaussart, P.; Petrella, T.; et al. Rituximab plus gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in patients with refractory/relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who are not candidates for high-dose therapy. A phase II Lymphoma Study Association trial. Haematologica 2013, 98, 1726–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.P.; Fu, D.; Li, J.Y.; Hu, J.D.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.F.; Yu, H.; Zhao, X.; Huang, Y.H.; Jiang, L.; et al. Anthracycline dose optimisation in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A multicentre, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019, 6, e328–e337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Goto, H.; Sawada, M.; Yamada, T.; Fukuno, K.; Kasahara, S.; Shibata, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Mabuchi, R.; et al. R-THP-COP versus R-CHOP in patients younger than 70 years with untreated diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A randomized, open-label, noninferiority phase 3 trial. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 36, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, P.A.; Townsend, W.; Webb, A.; Counsell, N.; Pocock, C.; Smith, P.; Jack, A.; El-Mehidi, N.; Johnson, P.W.; Radford, J.; et al. De novo treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, gemcitabine, and prednisolone in patients with cardiac comorbidity: A United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucci, A.; Merli, F.; Fabbri, A.; Marcheselli, L.; Pagani, C.; Puccini, B.; Marino, D.; Zanni, M.; Pennese, E.; Flenghi, L.; et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in octogenarians aged 85 and older can benefit from treatment with curative intent: A report on 129 patients prospectively registered in the Elderly Project of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi (FIL). Haematologica 2023, 108, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skin Nontumor. Neutrophilic and Eosinophilic Dermatoses. Pyoderma Gangrenosum. Available online: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skinnontumorpyodermagangrenosum.html (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Skin Nonmelanocytic Tumor. Lymphoma and Related Disorders. Primary Cutaneous B Cell Lymphoma (PCBCL). Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma, Leg Type. Available online: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lymphomadiffuselargeBcellleg.html (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Skin Nonmelanocytic Tumor. Lymphoma and Related Disorders. Primary Cutaneous B Cell Lymphoma (PCBCL). Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma. Available online: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lymphomafollicularcutaneous.html (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Lymphoma & Related Disorders. Mature B cell Neoplasms. DLBCL and Large B Cell Lymphomas with High Grade Features DLBCL, NOS. Available online: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lymphomadiffuse.html (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Lymphoma & Related Disorders. Mature B Cell Neoplasms. Large B Cell Lymphomas-Special Subtypes. EBV+ DLBCL. Available online: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lymphomadiffuseEBV.html (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Skin Nonmelanocytic Tumor. Lymphoma and Related Disorders. Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma (CTCL). Lymphomatoid Papulosis. Available online: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticlymphomatoidpapulosis.html (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Skin Nonmelanocytic Tumor. Lymphoma and Related Disorders. Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma (CTCL). Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Available online: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticanaplasticlargecell.html (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Kozłowska, A.; Gorzkowski, M.; Obtułowicz, A.; Wojas-Pelc, A.; Jaworek, A. Pyoderma gangrenosum as a possible paraneoplastic disease—Case study and literature review. Dermatol. Rev./Przegl. Dermatol. 2023, 110, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weenig, R.H.; Davis, M.D.; Dahl, P.R.; Su, W.P. Skin ulcers misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1412–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagnon, C.M.; Fracica, E.A.; Patel, A.A.; Camilleri, M.J.; Murad, M.H.; Dingli, D.; Wetter, D.A.; Tolkachjov, S.N. Pyoderma gangrenosum in hematologic malignancies: A systematic review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 1346–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jockenhöfer, F.; Wollina, U.; Salva, K.A.; Benson, S.; Dissemond, J. The PARACELSUS score: A novel diagnostic tool for pyoderma gangrenosum. Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 180, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maverakis, E.; Ma, C.; Shinkai, K.; Fiorentino, D.; Callen, J.P.; Wollina, U.; Marzano, A.V.; Wallach, D.; Kim, K.; Schadt, C.; et al. Diagnostic Criteria of Ulcerative Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Delphi Consensus of International Experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boostani, M.; Bánvölgyi, A.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Goldfarb, N.; Suppa, M.; Goldust, M.; Lőrincz, K.; Kiss, T.; Nádudvari, N.; Holló, P.; et al. Large language models in evaluating hidradenitis suppurativa from clinical images. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, e1052–e1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boostani, M.; Bánvölgyi, A.; Goldust, M.; Cantisani, C.; Pietkiewicz, P.; Lőrincz, K.; Holló, P.; Wikonkál, N.M.; Paragh, G.; Kiss, N. Diagnostic Performance of GPT-4o and Gemini Flash 2.0 in Acne and Rosacea. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 1881–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Criterion | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Major criteria | Progressive disease Absence of differential diagnoses Reddish-violaceous wound margin | 3 points each |

| Minor criteria | Alleviation due to immunosuppressive drugs Characteristically irregular (bizarre) wound shape Extreme pain (VAS > 4) Localized pathergy phenomenon | 2 points each |

| Additional criteria | Suppurative inflammation in histopathology Undermined wound border Systemic disease associated | 1 point each |

| Category | Criterion |

|---|---|

| Major criteria | Biopsy of ulcer edge demonstrating neutrophilic infiltrate |

| Minor criteria | Exclusion of infection Pathergy History of inflammatory bowel disease or inflammatory arthritis History of papule, pustule, or vesicle ulcerating within 4 days of appearing Peripheral erythema, undermining border, and tenderness at ulceration site Multiple ulcerations, at least 1 on anterior lower leg Cribriform or “wrinkled paper” scar(s) at healed ulcer sites Decreased ulcer size within 1 month of initiating immunosuppressive medication(s) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Markowska, M.; Chętko, Ł.; Bień, N.; Rajczak, M.; Ciążyńska, M.; Narbutt, J.; Lesiak, A. Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma Imitating Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Rare and Complex Diagnostic Challenge. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031138

Markowska M, Chętko Ł, Bień N, Rajczak M, Ciążyńska M, Narbutt J, Lesiak A. Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma Imitating Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Rare and Complex Diagnostic Challenge. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031138

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkowska, Maria, Łukasz Chętko, Natalia Bień, Maria Rajczak, Magdalena Ciążyńska, Joanna Narbutt, and Aleksandra Lesiak. 2026. "Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma Imitating Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Rare and Complex Diagnostic Challenge" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031138

APA StyleMarkowska, M., Chętko, Ł., Bień, N., Rajczak, M., Ciążyńska, M., Narbutt, J., & Lesiak, A. (2026). Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma Imitating Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Rare and Complex Diagnostic Challenge. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031138