Premenstrual Syndrome and Nutritional Factors: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence and Clinical Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

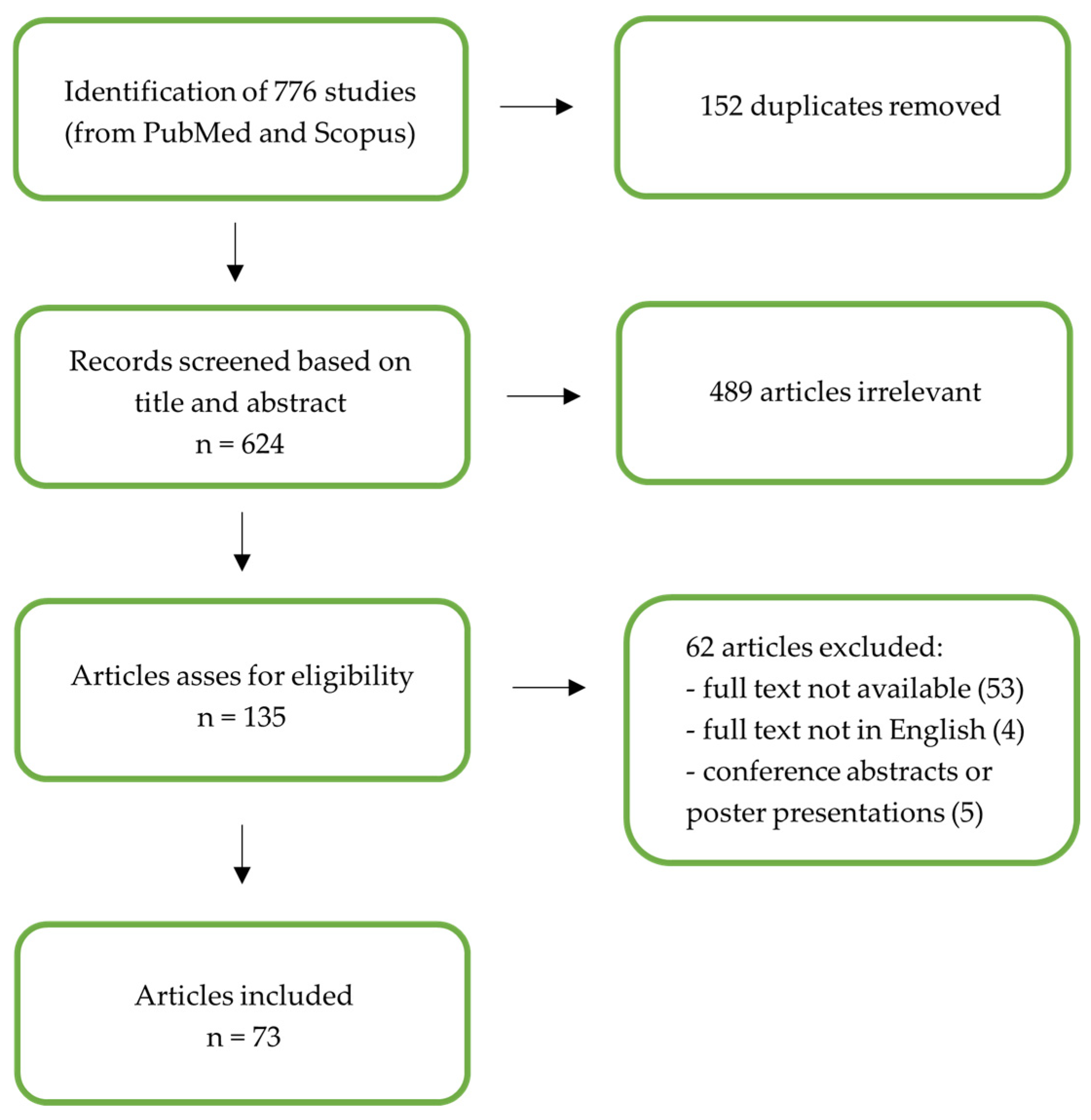

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiology

3.2. Pathogenesis

3.3. Symptoms and Diagnosis

3.4. Classification

3.5. Comorbidity

3.6. Medical Therapy

3.6.1. Hormonal Treatment

3.6.2. GnRH Agonist and Antagonist Treatment

3.6.3. Antidepressant Medication

3.6.4. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

3.6.5. Physical Activity

3.7. Nutritional Factor

3.7.1. Macronutrients

3.7.2. Micronutrients and Vitamins

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Finding

4.2. Comparison with the Existing Literature and Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yonkers, K.A.; O’Brien, P.M.; Eriksson, E. Premenstrual syndrome. Lancet 2008, 371, 1200–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittchen, H.-U.; Becker, E.; Lieb, R.; Krause, P. Prevalence, incidence and stability of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the community. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modzelewski, S.; Oracz, A.; Żukow, X.; Iłendo, K.; Śledzikowka, Z.; Waszkiewicz, N. Premenstrual syndrome: New insights into etiology and review of treatment methods. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1363875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of Premenstrual Disorders: ACOG Clinical Practice Guideline No. 7. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 142, 1516–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direkvand-Moghadam, A.; Sayehmiri, K.; Delpisheh, A.; Kaikhavandi, S. Epidemiology of Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS)-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR 2014, 8, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siminiuc, R.; Ţurcanu, D. Impact of nutritional diet therapy on premenstrual syndrome. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1079417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J.; Bouyer, J.; Trussell, J.; Moreau, C. Premenstrual syndrome prevalence and fluctuation over time: Results from a French population-based survey. J. Women’s Health 2009, 18, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T.; Tasaka, K.; Sakata, M.; Murata, Y. Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder in Japanese women. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2006, 9, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschudin, S.; Bertea, P.C.; Zemp, E. Prevalence and predictors of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder in a population-based sample. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2010, 13, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Luo, S.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J.; Ji, L. Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder in a population-based sample in China. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012, 162, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andualem, F.; Melkam, M.; Takelle, G.M.; Nakie, G.; Tinsae, T.; Fentahun, S.; Rtbey, G.; Seid, J.; Gedef, G.M.; Bitew, D.A.; et al. Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome and its associated factors in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1338304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh Trieu Ngo, V.; Bui, L.P.; Hoang, L.B.; Tran, M.T.T.; Nguyen, H.V.Q.; Tran, L.M.; Pham, T.T. Associated factors with Premenstrual syndrome and Premenstrual dysphoric disorder among female medical students: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0278702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hantsoo, L.; Payne, J.L. Towards understanding the biology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: From genes to GABA. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 149, 105168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudipally, P.R.; Sharma, G.K. Premenstrual Syndrome. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, E.B.; Wells, C.; Rasor, M.O. The Association of Inflammation with Premenstrual Symptoms. J. Women’s Health 2016, 25, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertone-Johnson, E.R.; Ronnenberg, A.G.; Houghton, S.C.; Nobles, C.; Zagarins, S.E.; Takashima-Uebelhoer, B.B.; Faraj, J.L.; Whitcomb, B.W. Association of inflammation markers with menstrual symptom severity and premenstrual syndrome in young women. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 1987–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, V.T.; Ballard, J.; Diamond, M.P.; Mannix, L.K.; Derosier, F.J.; Lener, S.E.; Krishen, A.; McDonald, S.A. Relief of menstrual symptoms and migraine with a single-tablet formulation of sumatriptan and naproxen sodium. J. Women’s Health 2014, 23, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, H.; Luecking, N.; Engel, S.; Blecker, M.K.; Knaevelsrud, C.; Schumacher, S. Menstrual cycle-related changes in HPA axis reactivity to acute psychosocial and physiological stressors—A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 150, 105212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatzkin, R.R.; Bunevicius, A.; Forneris, C.A.; Girdler, S. Menstrual mood disorders are associated with blunted sympathetic reactivity to stress. J. Psychosom. Res. 2014, 76, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, W. Psychological stress dysfunction in women with premenstrual syndrome. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanfar, S.; Lye, M.S.; Krishnarajah, I.S. The heritability of premenstrual syndrome. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2011, 14, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M.; Sacher, J. Stress, sex hormones, inflammation, and major depressive disorder: Extending Social Signal Transduction Theory of Depression to account for sex differences in mood disorders. Psychopharmacology 2019, 236, 3063–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Dai, W.; Su, M.; Wang, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, T.; Zheng, F.; Sun, P. The potential role of the orexin system in premenstrual syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1266806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmeister, S.; Bodden, S. Premenstrual Syndrome and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Am. Fam. Physician 2016, 94, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Itriyeva, K. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder in adolescents. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2022, 52, 101187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- First, M.B.; Clarke, D.E.; Yousif, L.; Eng, A.M.; Gogtay, N.; Appelbaum, P.S. DSM-5-TR: Rationale, Process, and Overview of Changes. Psychiatr. Serv. 2023, 74, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T. Premenstrual disorders: Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2023, 49, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeri, L.; Andersson, K.L.; Angioni, S.; Arena, A.; Arena, S.; Bartiromo, L.; Berlanda, N.; Bonin, C.; Candiani, M.; Centini, G.; et al. How to Manage Endometriosis in Adolescence: The Endometriosis Treatment Italian Club Approach. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martire, F.G.; Costantini, E.; d’Abate, C.; Capria, G.; Piccione, E.; Andreoli, A. Endometriosis and Nutrition: Therapeutic Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parazzini, F.; Viganò, P.; Candiani, M.; Fedele, L. Diet and endometriosis risk: A literature review. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2013, 26, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martire, F.G.; Costantini, E.; Ianes, I.; d’Abate, C.; De Bonis, M.; Capria, G.; Piccione, E.; Andreoli, A. Nutrition and Uterine Fibroids: Clinical Impact and Emerging Therapeutic Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevatte, T.; O’Brien, P.M.; Bäckström, T.; Brown, C.; Dennerstein, L.; Endicott, J.; Epperson, C.N.; Eriksson, E.; Freeman, E.W.; Halbreich, U.; et al. ISPMD consensus on the management of premenstrual disorders. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2013, 16, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahat, A.; Falach-Malik, A.; Haj, O.; Shatz, Z.; Ben-Horin, S. Change in bowel habits during menstruation: Are IBD patients different? Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13, 1756284820929806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.M.; Nam, C.M.; Kim, Y.N.; Lee, S.A.; Kim, E.H.; Hong, S.P.; Kim, T.I.; Kim, W.H.; Cheon, J.H. The effect of the menstrual cycle on inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective study. Gut Liver 2013, 7, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, S.V.; Sable, K.; Hanauer, S.B. The menstrual cycle and its effect on inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: A prevalence study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1998, 93, 1867–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzelant, G.; Ozguler, Y.; Esatoglu, S.N.; Karatemiz, G.; Ozdogan, H.; Yurdakul, S.; Yazici, H.; Seyahi, E. Exacerbation of Behçet’s syndrome and familial Mediterranean fever with menstruation. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2017, 35, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Neri, B.; Russo, C.; Mossa, M.; Martire, F.G.; Selntigia, A.; Mancone, R.; Calabrese, E.; Rizzo, G.; Exacoustos, C.; Biancone, L. High Frequency of Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nested Case-Control Study. Dig. Dis. 2023, 41, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, S.; Gustafsson, J.Å. Estrogen receptors: Therapies targeted to receptor subtypes. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 89, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Gong, X.; Yang, X.; Shang, X.; Du, Q.; Liao, Q.; Xie, R.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J. The roles of estrogen and estrogen receptors in gastrointestinal disease. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 5673–5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzi, A.; Lenz, A.M.; Labonte, M.J.; Lenz, H.J. Molecular pathways: Estrogen pathway in colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 5842–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principi, M.; Barone, M.; Pricci, M.; De Tullio, N.; Losurdo, G.; Ierardi, E.; Di Leo, A. Ulcerative colitis: From inflammation to cancer. Do estrogen receptors have a role? World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 11496–11504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierdominici, M.; Maselli, A.; Varano, B.; Barbati, C.; Cesaro, P.; Spada, C.; Zullo, A.; Lorenzetti, R.; Rosati, M.; Rainaldi, G.; et al. Linking estrogen receptor β expression with inflammatory bowel disease activity. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 40443–40451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, M.; Fichna, J.; Bashashati, M.; Habibi, S.; Sibaev, A.; Timmermans, J.P.; Storr, M. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor and estrogen receptor ligands regulate colonic motility and visceral pain. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2017, 29, e13025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, B.; Dong, L.; Guo, X.; Jiang, J.; He, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Zhao, J. Expression of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor in irritable bowel syndrome and its clinical significance. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 2238–2246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parlak, E.; Dağli, U.; Alkim, C.; Dişibeyaz, S.; Tunç, B.; Ulker, A.; Sahin, B. Pattern of gastrointestinal and psychosomatic symptoms across the menstrual cycle in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 14, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, M.T.; Graff, L.A.; Targownik, L.E.; Downing, K.; Shafer, L.A.; Rawsthorne, P.; Bernstein, C.N.; Avery, L. Gastrointestinal symptoms before and during menses in women with IBD. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 36, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selntigia, A.; Exacoustos, C.; Ortoleva, C.; Russo, C.; Monaco, G.; Martire, F.G.; Rizzo, G.; Della-Morte, D.; Mercuri, N.B.; Albanese, M. Correlation between endometriosis and migraine features: Results from a prospective case-control study. Cephalalgia 2024, 44, 3331024241235210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, P.E.; Rubinow, D.R.; Nieman, L.K.; Koziol, D.E.; Morrow, A.L.; Schiller, C.E.; Cintron, D.; Thompson, K.D.; Khine, K.K.; Schmidt, P.J. 5α-Reductase Inhibition Prevents the Luteal Phase Increase in Plasma Allopregnanolone Levels and Mitigates Symptoms in Women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiranini, L.; Nappi, R.E. Recent advances in understanding/management of premenstrual dysphoric disorder/premenstrual syndrome. Fac. Rev. 2022, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilbaz, B.; Aksan, A. Premenstrual syndrome, a common but underrated entity: Review of the clinical literature. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2021, 22, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, E.; Sundblad, C.; Lisjö, P.; Modigh, K.; Andersch, B. Serum levels of androgens are higher in women with premenstrual irritability and dysphoria than in controls. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1992, 17, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, U.; Krattenmacher, R.; Slater, E.P.; Fritzemeier, K.H. The novel progestin drospirenone and its natural counterpart progesterone: Biochemical profile and antiandrogenic potential. Contraception 1996, 54, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlstein, T.B.; Bachmann, G.A.; Zacur, H.A.; Yonkers, K.A. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with a new drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive formulation. Contraception 2005, 72, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, L.M.; Kaptein, A.A.; Helmerhorst, F.M. Oral contraceptives containing drospirenone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2, CD006586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström-Poromaa, I.; Comasco, E.; Sumner, R.; Luders, E. Progesterone—Friend or foe? Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2020, 59, 100856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardoy, M.C.; Serra, M.; Carta, M.G.; Contu, P.; Pisu, M.G.; Biggio, G. Increased neuroactive steroid concentrations in women with bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2006, 26, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naheed, B.; Kuiper, J.H.; Uthman, O.A.; O’Mahony, F.; O’Brien, P.M. Non-contraceptive oestrogen-containing preparations for controlling symptoms of premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 3, CD010503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlini, S.V.; Lanza di Scalea, T.; McNally, S.T.; Lester, J.; Deligiannidis, K.M. Management of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Women’s Health 2022, 14, 1783–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbreich, U.; Freeman, E.W.; Rapkin, A.J.; Cohen, L.S.; Grubb, G.S.; Bergeron, R.; Smith, L.; Mirkin, S.; Constantine, G.D. Continuous oral levonorgestrel/ethinyl estradiol for treating premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Contraception 2012, 85, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleknaviciute, J.; Tulen, J.H.M.; De Rijke, Y.B.; Bouwkamp, C.G.; van der Kroeg, M.; Timmermans, M.; Wester, V.L.; Bergink, V.; Hoogendijk, W.J.G.; Tiemeier, H.; et al. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device potentiates stress reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 80, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merki-Feld, G.S.; Apter, D.; Bartfai, G.; Grandi, G.; Haldre, K.; Lech, M.; Lertxundi, R.; Lete, I.; Lobo Abascal, P.; Raine, S.; et al. ESC expert statement on the effects on mood of the natural cycle and progestin-only contraceptives. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2017, 22, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, R.; Kay, V.J. Compliance and user satisfaction with the intra-uterine contraceptive device in Family Planning Service: The results of a survey in Fife, Scotland, August 2004. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2006, 11, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyatt, K.M.; Dimmock, P.W.; Ismail, K.M.; Jones, P.W.; O’Brien, P.M. The effectiveness of GnRHa with and without ‘add-back’ therapy in treating premenstrual syndrome: A meta analysis. BJOG 2004, 111, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copperman, A.B.; Benadiva, C. Optimal usage of the GnRH antagonists: A review of the literature. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. RBE 2013, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, S.W.; Zhang, R.; Tan, Z.; Chung, J.P.W.; Zhang, T.; Wang, C.C. Pharmaceuticals targeting signaling pathways of endometriosis as potential new medical treatment: A review. Med. Res. Rev. 2021, 41, 2489–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Management of Premenstrual Syndrome: Green-top Guideline No. 48. BJOG 2017, 124, e73–e105. [CrossRef]

- Halbreich, U.; O’Brien, P.M.; Eriksson, E.; Bäckström, T.; Yonkers, K.A.; Freeman, E.W. Are there differential symptom profiles that improve in response to different pharmacological treatments of premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder? CNS Drugs 2006, 20, 523–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza di Scalea, T.; Pearlstein, T. Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Med. Clin. North Am. 2019, 103, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjoribanks, J.; Brown, J.; O’Brien, P.M.; Wyatt, K. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD001396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.W.; Rickels, K.; Sondheimer, S.J.; Polansky, M.; Xiao, S. Continuous or intermittent dosing with sertraline for patients with severe premenstrual syndrome or premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullayikudi, T.; Preman, S.; Sood, A. The clinical impact and management of premenstrual syndrome. Obstet. Gynaecol. Reprod. Med. 2025, 35, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martire, F.G.; Costantini, E.; D’Abate, C.; Schettini, G.; Sorrenti, G.; Centini, G.; Zupi, E.; Lazzeri, L. Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: From Pathogenesis to Follow-Up. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulino, F.A.; Dilisi, V.; Capriglione, S.; Cannone, F.; Catania, F.; Martire, F.G.; Tuscano, A.; Gulisano, M.; D’urso, V.; Palumbo, M.A.; et al. Anti-Mullerian Hormone (AMH) and adenomyosis: Mini-review of literature of the last 5 years. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1014519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, S.C.; Manson, J.E.; Whitcomb, B.W.; Hankinson, S.E.; Troy, L.M.; Bigelow, C.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R. Carbohydrate and fiber intake and the risk of premenstrual syndrome. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashim, M.S.; Obaideen, A.A.; Jahrami, H.A.; Radwan, H.; Hamad, H.J.; Owais, A.A.; Alardah, L.G.; Qiblawi, S.; Al-Yateem, N.; Faris, M.A.E. Premenstrual Syndrome Is Associated with Dietary and Lifestyle Behaviors among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study from Sharjah, UAE. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, G.B.; Marley, J.; Miles, H.; Willson, K. Changes in nutrient intake during the menstrual cycle of overweight women with premenstrual syndrome. Br. J. Nutr. 2001, 85, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.W.; Stout, A.L.; Endicott, J.; Spiers, P. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome with a carbohydrate-rich beverage. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2002, 77, 253–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, R.; ZareMehrjardi, F.; Heidarzadeh-Esfahani, N.; Hughes, J.A.; Reid, R.E.R.; Borghei, M.; Ardekani, F.M.; Shahraki, H.R. Dietary intake of micronutrients are predictor of premenstrual syndrome, a machine learning method. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 55, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoradiFili, B.; Ghiasvand, R.; Pourmasoumi, M.; Feizi, A.; Shahdadian, F.; Shahshahan, Z. Dietary patterns are associated with premenstrual syndrome: Evidence from a case-control study. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asarian, L.; Geary, N. Estradiol enhances cholecystokinin-dependent lipid-induced satiation and activates estrogen receptor-alpha-expressing cells in the nucleus tractus solitarius of ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 5656–5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farasati, N.; Siassi, F.; Koohdani, F.; Qorbani, M.; Abashzadeh, K.; Sotoudeh, G. Western dietary pattern is related to premenstrual syndrome: A case-control study. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 2016–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, S.C.; Manson, J.E.; Whitcomb, B.W.; Hankinson, S.E.; Troy, L.M.; Bigelow, C.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R. Intake of dietary fat and fat subtypes and risk of premenstrual syndrome in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 118, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, S.C.; Manson, J.E.; Whitcomb, B.W.; Hankinson, S.E.; Troy, L.M.; Bigelow, C.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R. Protein intake and the risk of premenstrual syndrome. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1762–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oboza, P.; Ogarek, N.; Wójtowicz, M.; Rhaiem, T.B.; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M.; Kocełak, P. Relationships between Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) and Diet Composition, Dietary Patterns and Eating Behaviors. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chocano-Bedoya, P.O.; Manson, J.E.; Hankinson, S.E.; Johnson, S.R.; Chasan-Taber, L.; Ronnenberg, A.G.; Bigelow, C.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R. Intake of selected minerals and risk of premenstrual syndrome. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 177, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, F.; Ozgoli, G.; Rahnemaie, F.S. A systematic review of the role of vitamin D and calcium in premenstrual syndrome. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2019, 62, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertone-Johnson, E.R.; Chocano-Bedoya, P.O.; Zagarins, S.E.; Micka, A.E.; Ronnenberg, A.G. Dietary vitamin D intake, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels and premenstrual syndrome in a college-aged population. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 121, 434–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaei, S.; Akbari Sene, A.; Norouzi, S.; Berangi, Y.; Arabian, S.; Lak, P.; Dabbagh, A. The relationship between serum vitamin D level and premenstrual syndrome in Iranian women. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2016, 14, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Avan, A.; Sadeghnia, H.R.; Esmaeili, H.; Tayefi, M.; Ghasemi, F.; Nejati Salehkhani, F.; Arabpour-Dahoue, M.; Rastgar-Moghadam, A.; Ferns, G.A.; et al. High dose vitamin D supplementation can improve menstrual problems, dysmenorrhea, and premenstrual syndrome in adolescents. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2018, 34, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartagni, M.; Cicinelli, M.V.; Tartagni, M.V.; Alrasheed, H.; Matteo, M.; Baldini, D.; De Salvia, M.; Loverro, G.; Montagnani, M. Vitamin D Supplementation for Premenstrual Syndrome-Related Mood Disorders in Adolescents with Severe Hypovitaminosis D. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2016, 29, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, Z.; Dehkordi, M.A.; Alipour, A.; Mohtashami, T. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome: Appraising the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy in addition to calcium supplement plus vitamin D. PsyCh J. 2018, 7, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajehei, M.; Abdali, K.; Parsanezhad, M.E.; Tabatabaee, H.R. Effect of treatment with dydrogesterone or calcium plus vitamin D on the severity of premenstrual syndrome. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2009, 105, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadkhah, H.; Ebrahimi, E.; Fathizadeh, N. Evaluating the effects of vitamin D and vitamin E supplement on premenstrual syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2016, 21, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arab, A.; Golpour-Hamedani, S.; Rafie, N. The Association Between Vitamin D and Premenstrual Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Current Literature. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2019, 38, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeitoun, T.; Dehghan Noudeh, N.; Garcia-Bailo, B.; El-Sohemy, A. Genetics of Iron Metabolism and Premenstrual Symptoms: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, F.; Amani, R.; Tarrahi, M.J. Effect of Zinc Supplementation on Physical and Psychological Symptoms, Biomarkers of Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Young Women with Premenstrual Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 194, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chocano-Bedoya, P.O.; Manson, J.E.; Hankinson, S.E.; Willett, W.C.; Johnson, S.R.; Chasan-Taber, L.; Ronnenberg, A.G.; Bigelow, C.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R. Dietary B vitamin intake and incident premenstrual syndrome. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soheila, S.; Faezeh, K.; Kourosh, S.; Fatemeh, S.; Nasrollah, N.; Mahin, G.; Majid, A.S.; Mahmoud, B. Effects of vitamin B6 on premenstrual syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Chem. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 9, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahifard, S.; Rahmanian Koshkaki, A.; Moazamiyanfar, R. The effects of vitamin B1 on ameliorating the premenstrual syndrome symptoms. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2014, 6, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samieipour, S.; Tavassoli, E.; Heydarabadi, A.; Daniali, S.; Alidosti, M.; Kiani, F.; Pakseresht, M. Effect of calcium and vitamin B1 on the severity of premenstrual syndrome: A randomized control trial. Int. J. Pharm. Technol. 2016, 8, 18706–18717. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, M.M.; Dehghan Nayeri, N.; Mashhadi, M.; Varaei, S. Effect of omega-3 fatty acids on premenstrual syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2022, 48, 1293–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, A.M.; Bonnlander, H. Caffeine-containing beverages, total fluid consumption, and premenstrual syndrome. Am. J. Public Health 1990, 80, 1106–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, A.M.; Bonnlander, H.; Song, L.; Phillis, J.W. Do women with premenstrual symptoms self-medicate with caffeine? Epidemiology 1991, 2, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caan, B.; Duncan, D.; Hiatt, R.; Lewis, J.; Chapman, J.; Armstrong, M.A. Association between alcoholic and caffeinated beverages and premenstrual syndrome. J. Reprod. Med. 1993, 38, 630–636. [Google Scholar]

- Purdue-Smithe, A.C.; Manson, J.E.; Hankinson, S.E.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R. A prospective study of caffeine and coffee intake and premenstrual syndrome. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höller, M.; Steindl, H.; Abramov-Sommariva, D.; Kleemann, J.; Loleit, A.; Abels, C.; Stute, P. Use of Vitex agnus-castus in patients with menstrual cycle disorders: A single-center retrospective longitudinal cohort study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 309, 2089–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Ferreira, A.; Iacovou, M.; Kellow, N.J. Effect of nutritional interventions on the psychological symptoms of premenstrual syndrome in women of reproductive age: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, 280–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, H.; Pareek, P.; Sayyad, M.G.; Otiv, S. Association of Premenstrual Syndrome with Adiposity and Nutrient Intake Among Young Indian Women. Int. J. Women’s Health 2022, 14, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | Common Symptoms | Clinical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Affective/emotional | Irritability, anger, emotional lability, depressed mood, anxiety | Often predominant and more disabling in PMDD |

| Cognitive | Poor concentration, reduced interest, loss of control | Overlap with anxiety/depression; cyclicity is crucial |

| Behavioral | Sleep disturbances, food cravings, hyperphagia, social withdrawal | May mimic primary mood disorders without cycle documentation |

| Somatic | Mastalgia, bloating, headache, myalgia, bowel habit changes | Highly visible symptoms, insufficient alone without functional impact |

| System | Scope | Symptom Threshold | Key Requirements | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACOG | Gynecology | ≥1 affective or somatic symptom | Functional interference, cyclicity, often prospective confirmation | Less specific for PMDD |

| DSM-5-TR | Psychiatry | ≥5 symptoms | At least one mood symptom, defined time window, exclusion of PME | Risk of underdiagnosing disabling subthreshold cases |

| ISPMD | Multidisciplinary | No fixed threshold | Centrality of cyclicity and functional impact | Less standardized for epidemiology |

| ICD-10 | Clinical/epidemiological | Variable | Frequently used in observational studies | Limited overlap with DSM criteria |

| Author (Year) | Article Title | Study Design | Level of Evidence | Effects on PMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Houghton et al. (2018) [74] | Carbohydrate and fiber intake and the risk of premenstrual syndrome | Prospective cohort study | High | No association with fiber, carbohydrate, or protein intake |

| Hashim et al. (2019) [75] | Premenstrual Syndrome Is Associated with Dietary and Lifestyle Behaviors among University Students | Cross-sectional study | Moderate | Higher fat and simple carbohydrate intake; lower protein intake |

| Cross et al. (2001) [76] | Changes in nutrient intake during the menstrual cycle of overweight women with PMS | Observational longitudinal study | Moderate | Inverse association with fish and seafood intake |

| Freeman et al. (2002) [77] | Treatment of premenstrual syndrome with a carbohydrate-rich beverage | Nutritional intervention study | Moderate | Carbohydrate intake modulated PMS symptoms |

| Taheri et al. (2023) [78] | Dietary intake of micronutrients are predictor of PMS | Observational predictive study | Moderate | Simple carbohydrates and fried foods associated with worse symptoms |

| MoradiFili et al. (2020) [79] | Dietary patterns are associated with premenstrual syndrome | Case–control study | Moderate | Western diet increases risk; healthy patterns protective |

| Asarian & Geary (2007) [80] | Estradiol enhances lipid-induced satiation | Animal experimental study | Low | Indirect mechanistic evidence only |

| Farasati et al. (2015) [81] | Western dietary pattern is related to PMS | Case–control study | Moderate | Fruit intake reduces psychological symptoms |

| Houghton et al. (2017) [82] | Dietary fat and fat subtypes and PMS risk | Prospective cohort study | High | Stearic acid protective; maltose increases risk |

| Houghton et al. (2019) [83] | Protein intake and the risk of PMS | Prospective cohort study | High | No association with protein intake |

| Oboza et al. (2024) [84] | Relationships between PMS and Diet Composition | Narrative review | Moderate | No association with protein intake |

| Author (Year) | Article Title | Study Design | Level of Evidence | Main Effects on PMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oboza et al., 2024 [84] | Relationships between PMS and Diet Composition, Dietary Patterns and Eating Behaviors | Cross-sectional observational study | Low | Lower intake of calcium, magnesium and potassium associated with PMS |

| Chocano-Bedoya et al., 2013 [85] | Intake of selected minerals and risk of premenstrual syndrome | Prospective cohort study | Moderate | Calcium intake associated with reduced risk and severity of PMS |

| Abdi et al., 2019 [86] | Role of vitamin D and calcium in premenstrual syndrome | Systematic review | High | Vitamin D and calcium deficiency associated with PMS |

| Bertone-Johnson et al., 2010 [87] | Dietary vitamin D intake, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels and PMS | Observational study | Low | Low vitamin D levels associated with increased symptom severity |

| Rajaei et al., 2016 [88] | Serum vitamin D level and PMS in Iranian women | Case–control study | Low | No significant association between vitamin D and PMS |

| Bahrami et al., 2018 [89] | High-dose vitamin D supplementation in adolescents | Clinical trial | Moderate | Reduced dysmenorrhea and PMS symptoms |

| Tartagni et al., 2016 [90] | Vitamin D supplementation for PMS-related mood disorders | Randomized controlled trial | High | Improved mood symptoms and dysmenorrhea |

| Karimi et al., 2018 [91] | Calcium plus vitamin D in PMS treatment | Randomized controlled trial | High | Improved mood-related PMS symptoms |

| Arab et al., 2019 [94] | Vitamin D and PMS: systematic review and meta-analysis | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Very high | Reduced severity of PMS symptoms |

| Zeitoun et al., 2021 [95] | Genetics of iron metabolism and premenstrual symptoms | Mendelian randomization study | Moderate | Higher non-heme iron intake associated with lower PMS risk |

| Jafari et al., 2020 [96] | Effect of zinc supplementation on PMS | Double-blind randomized controlled trial | High | Reduced physical and psychological symptoms; improved quality of life |

| Chocano-Bedoya et al., 2011 [97] | Dietary B vitamin intake and incident PMS | Prospective cohort study | Moderate | Higher B vitamin intake associated with lower PMS risk |

| Soheila et al., 2016 [98] | Effects of vitamin B6 on PMS | Systematic review and meta-analysis | High | Overall symptom improvement, heterogeneous results |

| Abdollahifard et al., 2014 [99] | Effects of vitamin B1 on PMS symptoms | Meta-analysis | High | Improvement of physical and psychological symptoms |

| Samieipour et al., 2016 [100] | Effect of calcium and vitamin B1 on PMS severity | Randomized controlled trial | High | Significant reduction in symptom severity |

| Mohammadi et al., 2022 [101] | Effect of omega-3 fatty acids on PMS | Systematic review and meta-analysis | High | Reduction in PMS symptoms; duration-dependent |

| Rossignol et al., 1990–1991 [102,103] | Caffeine-containing beverages and PMS | Observational studies | Low | Higher caffeine intake associated with more severe symptoms |

| Caan et al., 1993; Purdue-Smithe et al., 2016 [104,105] | Caffeine/coffee intake and PMS | Observational study and prospective cohort | Low–Moderate | No consistent association with PMS |

| Höller et al., 2024 [106] | Use of Vitex agnus-castus in menstrual cycle disorders | Retrospective longitudinal cohort study | Moderate | Improved dysmenorrhea, mastodynia and quality of life |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Martire, F.G.; Costantini, E.; Ianes, I.; d’Abate, C.; De Bonis, M.; Piccione, E.; Andreoli, A. Premenstrual Syndrome and Nutritional Factors: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence and Clinical Implications. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031124

Martire FG, Costantini E, Ianes I, d’Abate C, De Bonis M, Piccione E, Andreoli A. Premenstrual Syndrome and Nutritional Factors: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence and Clinical Implications. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031124

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartire, Francesco Giuseppe, Eugenia Costantini, Ilaria Ianes, Claudia d’Abate, Maria De Bonis, Emilio Piccione, and Angela Andreoli. 2026. "Premenstrual Syndrome and Nutritional Factors: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence and Clinical Implications" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031124

APA StyleMartire, F. G., Costantini, E., Ianes, I., d’Abate, C., De Bonis, M., Piccione, E., & Andreoli, A. (2026). Premenstrual Syndrome and Nutritional Factors: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence and Clinical Implications. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031124