The Prognostic Value of Inflammatory Markers in Paediatric Acute Kidney Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Study Design and Participants

2.3. Data Collection and Definition

2.4. Statistical Analysis

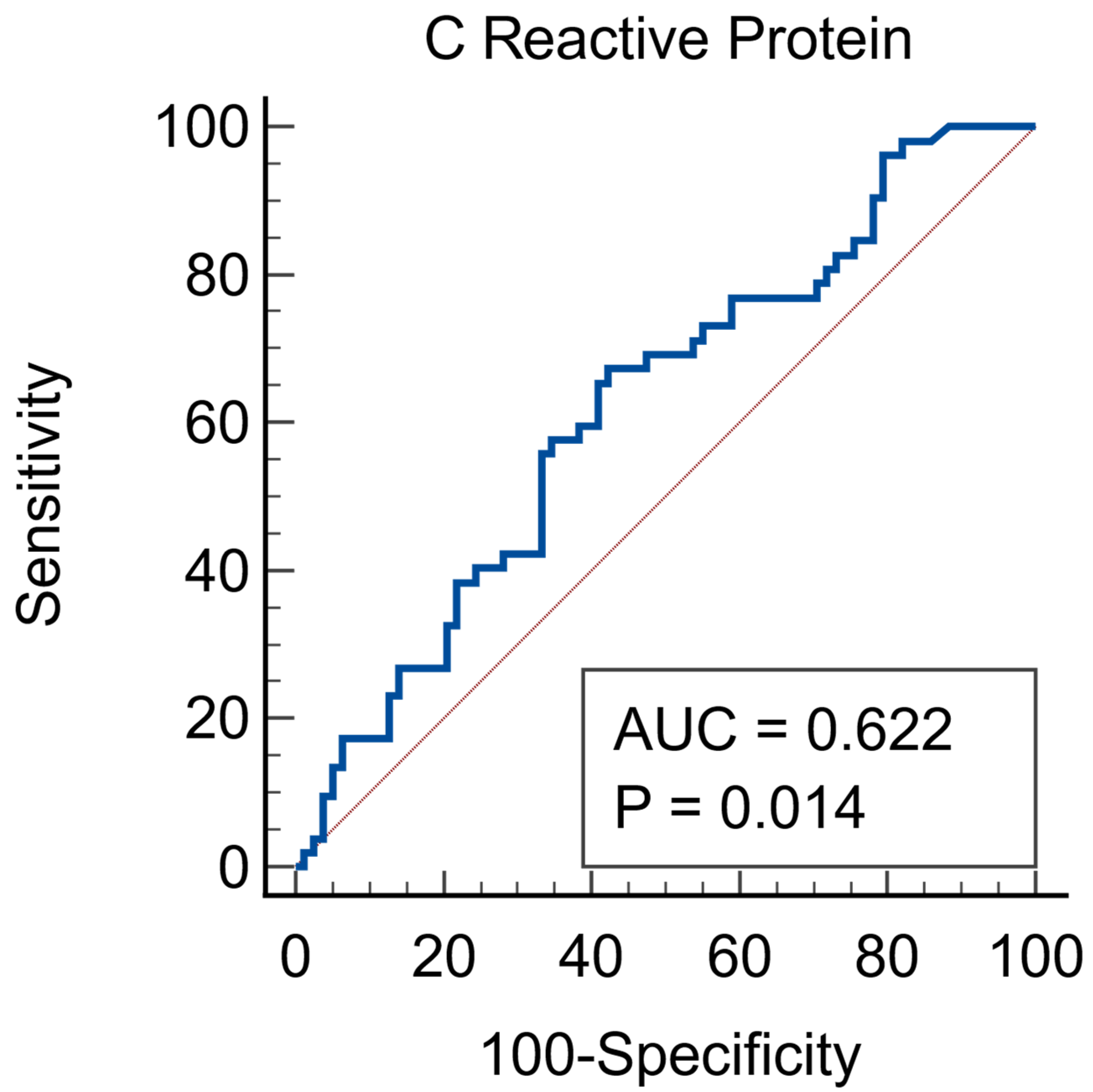

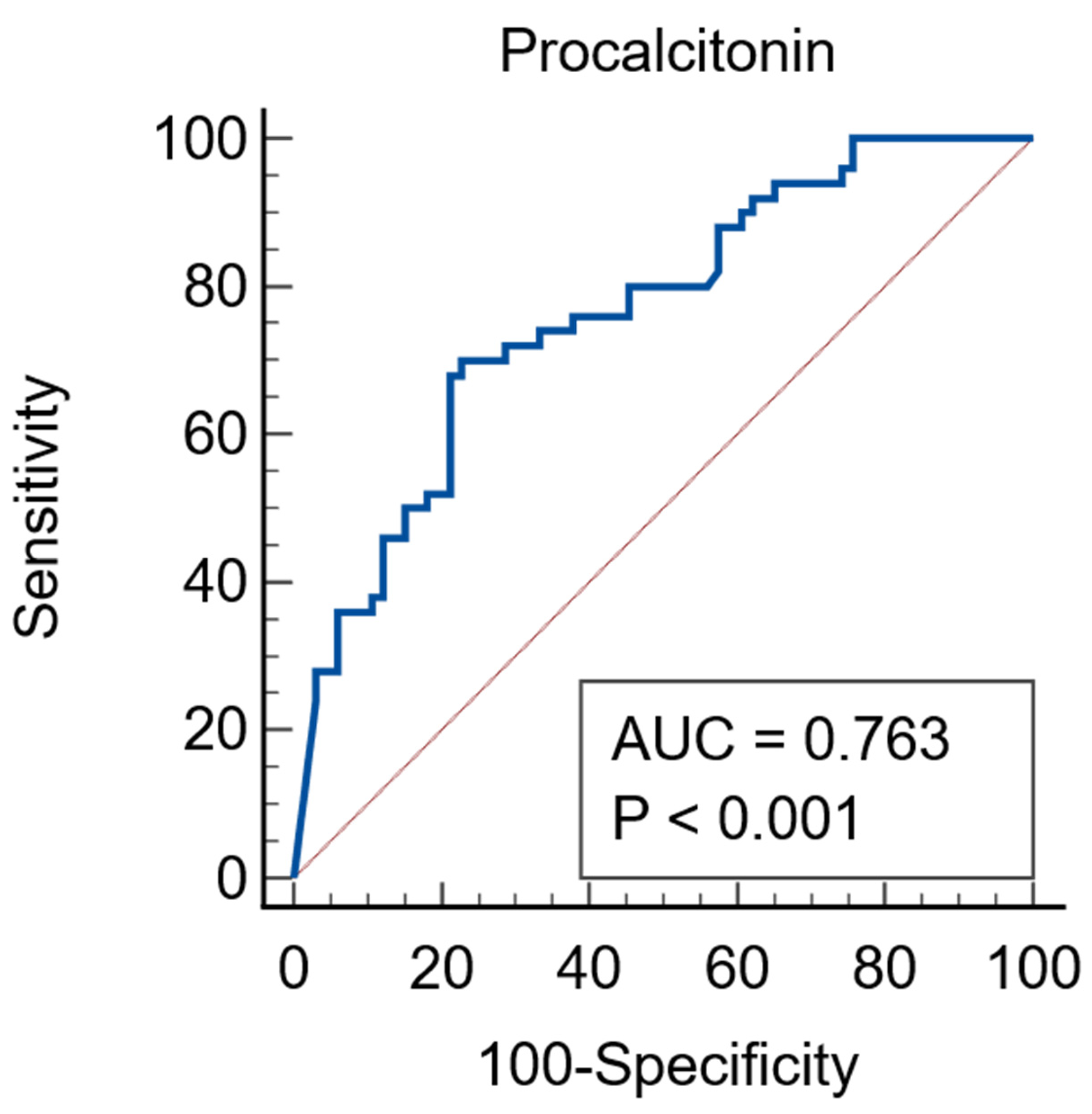

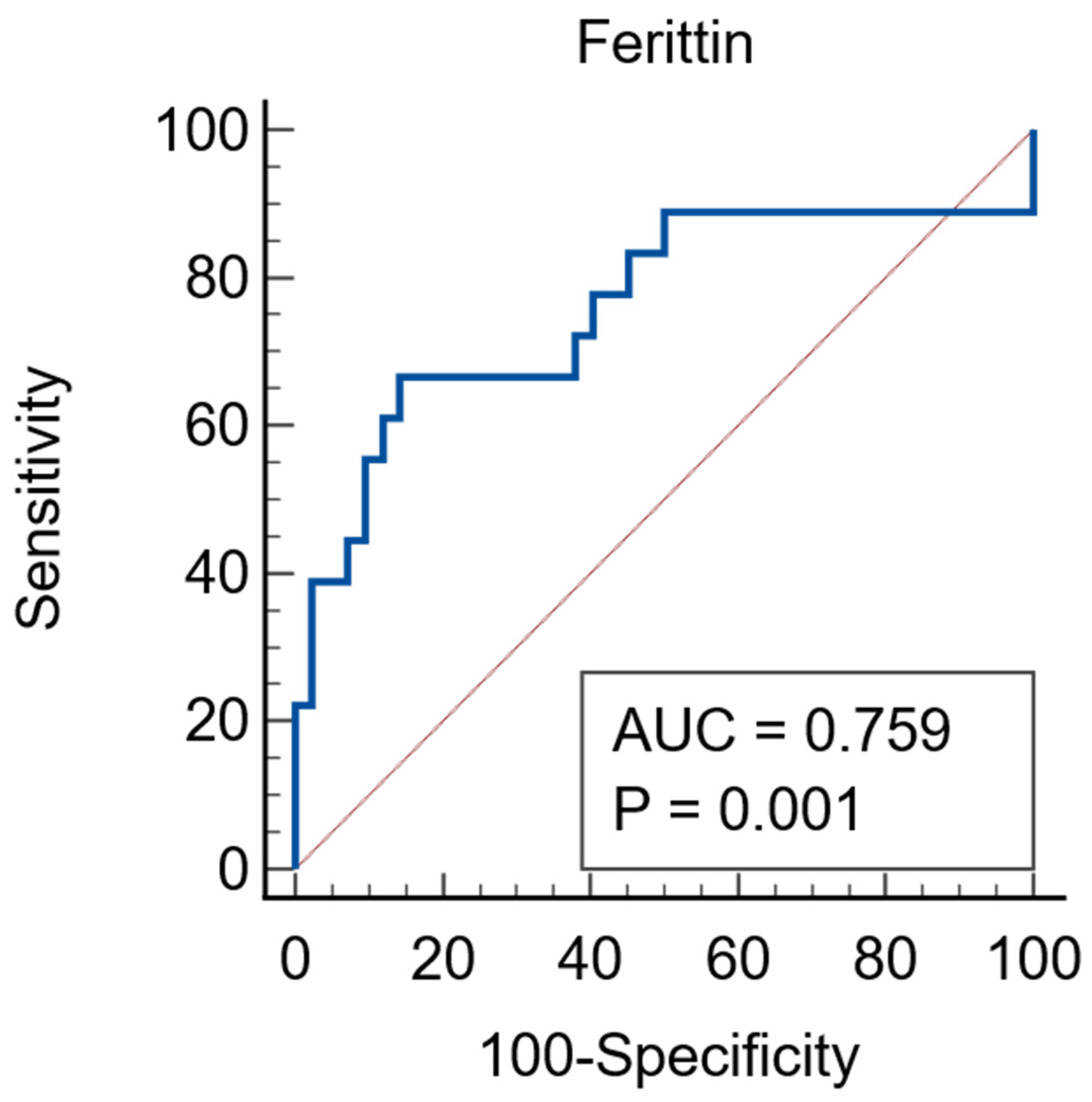

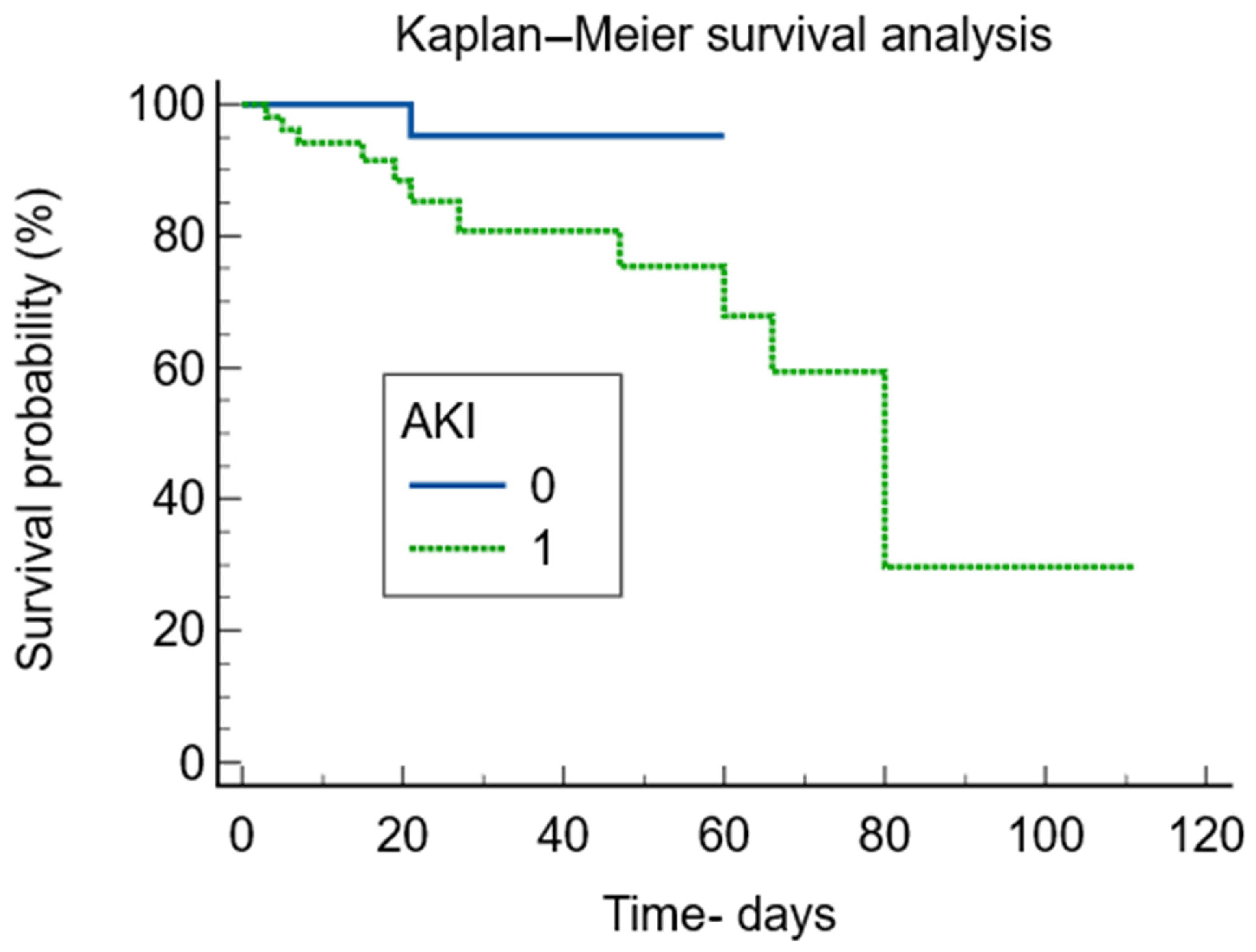

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| PCT | Procalcitonin |

| CRP | C reactive protein |

References

- Sutherland, S.M.; Alobaidi, R.; Gorga, S.M.; Iyengar, A.; Morgan, C.; Heydari, E.; Arikan, A.A.A.; Basu, R.K.; Goldstein, S.L.; Zappitelli, M.; et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in children: A report from the 26th Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) consensus conference. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2024, 39, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meena, J.; Mathew, G.; Kumar, J.; Chanchlani, R. Incidence of Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalized Children: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022058823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nechemia-Arbely, Y.; Barkan, D.; Pizov, G.; Shriki, A.; Rose-John, S.; Galun, E.; Axelrod, J.H. IL-6/IL-6R axis plays a critical role in acute kidney injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2008, 19, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murashima, M.; Nishimoto, M.; Kokubu, M.; Hamano, T.; Matsui, M.; Eriguchi, M.; Samejima, K.I.; Akai, Y.; Tsuruya, K. Inflammation as a predictor of acute kidney injury and mediator of higher mortality after acute kidney injury in non-cardiac surgery. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadke, R.; Singh, S.; Gupta, A.; Samel, S.S.; Taank, P. Correlation of Inflammatory Markers with Renal Dysfunction and Their Outcome in Symptomatic Adult COVID-19 Patients. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 42, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.Z.; Gu, Y.H.; Su, T.; Zhou, X.J.; Huang, J.W.; Sun, P.P.; Jia, Y.; Xu, D.M.; Wang, S.X.; Liu, G.; et al. Elevation of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels reflects renal interstitial inflammation in drug-induced acute tubulointerstitial nephritis. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, K.; Chung, W.; Kim, A.J.; Kim, H.; Ro, H.; Chang, J.H.; Lee, H.H.; Jung, J.Y. Association between acute kidney injury and serum procalcitonin levels and their diagnostic usefulness in critically ill patients. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y.; Feng, X.; Li, H.; Guo, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; et al. Interleukin-6, serum albumin levels, and acute kidney injury jointly predict in-hospital mortality in pediatric COVID-19 patients. Transl. Pediatr. 2025, 14, 2686–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygili, S.; Canpolat, N.; Cicek, R.Y.; Agbas, A.; Yilmaz, E.K.; Sakalli, A.A.K.; Aygun, D.; Akkoc, G.; Demirbas, K.C.; Konukoglu, D.; et al. Clinical and subclinical acute kidney injury in children with mild-to-moderate COVID-19. Pediatr. Res. 2023, 93, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Halaby, H.; Eid, R.; Elagamy, A.; El-Hussiny, A.; Moustafa, F.; Hammad, A.; Zeid, M. A retrospective analysis of acute kidney injury in children with post-COVID-19 multisystem inflammatory syndrome: Insights into promising outcomes. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2024, 50, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.R.; Garg, A.X.; Coca, S.G.; Devereaux, P.J.; Eikelboom, J.; Kavsak, P.; McArthur, E.; Thiessen-Philbrook, H.; Shortt, C.; Shlipak, M.; et al. Plasma IL-6 and IL-10 Concentrations Predict AKI and Long-Term Mortality in Adults after Cardiac Surgery. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2015, 26, 3123–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, T.P.; Watkins, A.J.; Velazquez, M.A.; Mathers, J.C.; Prentice, A.M.; Stephenson, J.; Barker, M.; Saffery, R.; Yajnik, C.S.; Eckert, J.J.; et al. Origins of lifetime health around the time of conception: Causes and consequences. Lancet 2018, 391, 1842–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renz, H.; Holt, P.G.; Inouye, M.; Logan, A.C.; Prescott, S.L.; Sly, P.D. An exposome perspective: Early-life events and immune development in a changing world. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, D.W.; Fasano, A.; Miller, G.W.; et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castell, J.V.; Gómez-Lechón, M.J.; David, M.; Andus, T.; Geiger, T.; Trullenque, R.; Fabra, R.; Heinrich, P.C. Interleukin-6 is the major regulator of acute phase protein synthesis in adult human hepatocytes. FEBS Lett. 1989, 242, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, J.; Baines, L.; Talbot, D.; MacFie, C. Severe anti-thymocyte globulin-induced cytokine release syndrome in a renal transplant patient. Anaesth. Rep. 2021, 9, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.K.; Jayalakshmi, K.M.D.; Arun, D.; Jayavardhini, S.; Karthikaa, S.H.; Sumetha, S.; Thiyagarajan, K. A short-term cross-sectional retrospective study on procalcitonin as a diagnostic aid for various infectious diseases. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannico, L.; Santobuono, V.E.; Fischetti, G.; Mazzone, F.; Parigino, D.; Savino, L.; Alfeo, M.; Milano, A.D.; Guaricci, A.I.; Ciccone, M.M.; et al. Kinetics of Procalcitonin, CRP, IL-6, and Presepsin in Heart Transplant Patients Undergoing Induction with Thymoglobulin (rATG). J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, I.; Fasih, A.; Wang, Y. The use of procalcitonin in the determination of severity of sepsis, patient outcomes and infection characteristics. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahar, L.A. Interleukin-6 and Procalcitonin as Potential Predictors of Acute Kidney Injury Occurrence in Patients with Sepsis. Rep. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 13, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zheng, H.; Luo, Z.; Yi, Y.; Liu, K.; Huo, Z.; You, Y.; Li, H.; Tang, M. Assessment value of interleukin-6, procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein early kinetics for initial antibiotic efficacy in patients with febrile neutropenia: A prospective study. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarei, H.; Azimi, A.; Ansarian, A.; Raad, A.; Tabatabaei, H.; Dizaji, S.R.; Saadatipour, N.; Dadras, A.; Ataei, N.; Hosseini, M.; et al. Incidence of acute kidney injury-associated mortality in hospitalized children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2025, 26, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2012, 2, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Huo, J.; Hu, Q.; Xu, J.; Chen, G.; Mo, J.; Zhou, T.; Jiang, J. Association between lactate dehydrogenase to albumin ratio and acute kidney injury in patients with sepsis: A retrospective cohort study. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2024, 28, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuer, S.; Aili, Z.; Guyha, N.; Kari, A.; Abuduheilili, W.; Abuduhaer, A. Predicting acute kidney injury in children with sepsis using red blood cell distribution and biomarkers (PCT, IL-6, CRP, and cystatin C). J. Med. Biochem. 2025, 44, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; He, H.; Jia, C.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y.; Liao, D. Meta-analysis of procalcitonin as a predictor for acute kidney injury. Medicine 2021, 100, e24999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.Z.; Wang, H.C.; Geng, Z.; Kan, Y.; Cao, X.; Yan, X.M. Iron-related protein in prediction of acute kidney injury in the pediatric population after cardiac surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2025, 20, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Lei, C.T.; Zhang, C. Interleukin-6 Signaling Pathway and Its Role in Kidney Disease: An Update. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikłaszewska, M.; Korohoda, P.; Zachwieja, K.; Mroczek, T.; Drożdż, D.; Sztefko, K.; Moczulska, A.; Pietrzyk, J.A. Serum interleukin 6 levels as an early marker of acute kidney injury on children after cardiac surgery. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. Off. Organ Wroc. Med. Univ. 2013, 22, 377–386. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Hou, L. IL-6 and diabetic kidney disease. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1465625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanski, G.; Marin, V.; Montero-Julian, F.; Mantovani, A.; Farnarier, C. IL-6: A regulator of the transition from neutrophil to monocyte recruitment during inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2003, 24, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkar, A.M.; Smith, J.; Tam, F.W.; Pusey, C.D.; Rees, A.J. Abrogation of glomerular injury in nephrotoxic nephritis by continuous infusion of interleukin-6. Kidney Int. 1997, 52, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andres-Hernando, A.; Okamura, K.; Bhargava, R.; Kiekhaefer, C.M.; Soranno, D.; Kirkbride-Romeo, L.A.; Gil, H.W.; Altmann, C.; Faubel, S. Circulating IL-6 upregulates IL-10 production in splenic CD4+ T cells and limits acute kidney injury-induced lung inflammation. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 1057–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Lu, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Xiao, C.; Meng, T.; Peng, L.; Gan, L.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Interleukin-22 exacerbates angiotensin II-induced hypertensive renal injury. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 109, 108840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.S.; Chatterjee, P.K.; Di Paola, R.; Mazzon, E.; Britti, D.; De Sarro, A.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Thiemermann, C. Endogenous interleukin-6 enhances the renal injury, dysfunction, and inflammation caused by ischemia/reperfusion. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 312, 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.A.; Horiuchi, S.; Topley, N.; Yamamoto, N.; Fuller, G.M. The soluble interleukin 6 receptor: Mechanisms of production and implications in disease. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, T. IL-6 in inflammation, autoimmunity and cancer. Int. Immunol. 2021, 33, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.E.; Maerz, M.D.; Buckner, J.H. IL-6: A cytokine at the crossroads of autoimmunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018, 55, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Nie, S.; Zhang, A.; Mao, J.; Liu, H.P.; Xia, H.; Xu, H.; Liu, Z.; Feng, S.; Zhou, W.; et al. Acute Kidney Injury among Hospitalized Children in China. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2018, 13, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.N.; Chen, H.L.; Tain, Y.L. Epidemiology and outcomes of community-acquired and hospital-acquired acute kidney injury in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Res. 2018, 83, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddourah, A.; Basu, R.K.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Goldstein, S.L. AWARE Investigators Epidemiology of Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill Children and Young Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignass, A.; Farrag, K.; Stein, J. Limitations of Serum Ferritin in Diagnosing Iron Deficiency in Inflammatory Conditions. Int. J. Chronic Dis. 2018, 2018, 9394060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, F.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Yu, L.; Ma, C.; Wang, R. Association of serum ferritin and all-cause mortality in AKI patients: A retrospective cohort study. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1368719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coca, S.G.; Yusuf, B.; Shlipak, M.G.; Garg, A.X.; Parikh, C.R. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2009, 53, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Total N = 131 | AKI N = 52 | Non-AKI N = 79 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age years * | 5.1 (1.42–10.87) | 4.5 (0.25–10) | 6 (2.27–11.02) | 0.053 |

| Sex—males | 74 (56.5%) | 30 (57.7%) | 44 (55.7%) | 0.822 |

| Urban environment | 72 (55%) | 22 (42.3%) | 50 (63.3%) | 0.018 |

| Deaths | 12 (9.2%) | 11 (21.2%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0.0001 |

| ICU Admission | 80 (61.1%) | 41 (78.8%) | 39 (49.4%) | 0.0007 |

| ICU stay—days (only for ICU patients) * | 8 (5–18) | 15 (6–20) | 6 (3–13) | 0.0034 |

| Sepsis | 42 (32.1%) | 22 (42.3%) | 20 (25.3%) | 0.0423 |

| Hospital stay—days * | 14 (8–29) | 21.5 (13–48.5) | 10 (6–22) | <0.0001 |

| Parameter | Total N = 131 | AKI N = 52 | Non-AKI N = 79 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDH * IU/L | 307 (250–554) | 543 (293–1140) | 276 (209–326) | <0.0001 |

| Peak serum creatinine * umol/L | 44 (28.25–72.25) | 86 (54.5–119) | 32 (23.75–44) | <0.0001 |

| Baseline creatinine * umol/L | 27 (21–36) | 28.5 (18–34.5) | 27 (22–37.75) | 0.91 |

| Urea * mmol/L | 4.74 (3.45–8.48) | 8.56 (5.55–19.3) | 3.93 (2.87–5.15) | <0.0001 |

| GOT * IU/L | 35 (21.25–72) | 61.5 (29.5–163.5) | 29 (19–42.25) | <0.0001 |

| GPT * IU/L | 23 (13–45) | 34 (15–102.5) | 20 (12–35.25) | 0.0026 |

| Hemoglobin 1 g/dL | 10.6 (2.14) | 9.91 (2.25) | 11.04 (1.96) | 0.0029 |

| Thrombocytes * N/mmc | 242,000 (129,250–378,500) | 150,000 (56,000–266,500) | 293,000 (182,000–436,250) | <0.0001 |

| CRP * mg/L | 55 (12.6–177.68) | 98.81 (26.82–236.51) | 37.03 (10.25–142.23) | 0.0184 |

| Procalcitonin * ng/mL | 3.05 (0.21–18.23) | 11.31 (1.37–83.63) | 0.81 (0.09–3.91) | <0.0001 |

| IL-6 * pg/mL | 34.15 (10.5–115.45) | 47.02 (14.24–121.4) | 28.3 (6.96–104.97) | 0.145 |

| Albumins 1 g/L | 28.12 (5) | 25.5 (4.86) | 30.15 (4.12) | <0.0001 |

| Leucocytes * N × 1000/mmc | 11.45 (7.06–18.17) | 13.33 (5.05–20.59) | 10.9 (7.06–17.31) | 0.284 |

| ESR * mm/h | 44.5 (18–81) | 45 (14–85) | 40 (18–74.75) | 0.771 |

| Ferritin * ng/mL | 230 (79.5–848) | 1218 (226–2336) | 147 (67–651) | 0.0016 |

| Parameter | Without AKI | AKI Stage 1 | AKI Stage 2 | AKI Stage 3 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 * pg/mL | 28.3 (6.96–104.97) | 43.59 (15.41–325.87) | 16.89 (8.57–75.09) | 62.62 (32.5–189.8) | 0.079 |

| CRP * mg/L | 37.03 (10.25–142.23) | 74.97 (9.37–302.3) | 64.68 (23.9–177.7) | 129.9 (51.57–240.88) | 0.072 |

| Ferritin * ng/mL | 147 (67–651) | 1344 (162.25–6132) | 1602 (971–2292) | 184 (46.75–597.25) | 0.002 a |

| LDH * IU/L | 276 (209.75–326.5) | 276.5 (264–808) | 569 (411.5–722.25) | 675 (319.5–1445) | 0.00001 b |

| Albumins ** g/L | 30.15 (4.11) | 28.28 (6.6) | 26.44 (3.78) | 23.74 (3.99) | <0.001 c |

| ESR * mm/h | 40 (18–74.75) | 57 (16.25–113) | 32.5 (10–54) | 60 (29.5–95) | 0.49 |

| PCT * ng/mL | 0.81 (0.09–3.91) | 4.93 (0.22–22.31) | 4.12 (0.44–17.38) | 35.73 (7.26–100) | <0.00001 d |

| Parameter | Total | AKI | Non-AKI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | 13 (9.9%) | 2 (3.8%) | 11 (13.9%) | 0.06 |

| Renal | 8 (6.1%) | 5 (9.6%) | 3 (3.8%) | 0.175 |

| Neurological | 10 (7.6%) | 6 (11.5%) | 4 (5.1%) | 0.17 |

| Inflammatory | 25 (19.1%) | 7 (13.5%) | 18 (22.8%) | 0.18 |

| Hematological | 17 (13%) | 9 (17.3%) | 8 (10.1%) | 023 |

| Surgical | 16 (12.2%) | 6 (11.5%) | 10 (12.7%) | 0.84 |

| Pulmonary | 31 (23.7%) | 9 (17.3%) | 22 (27.8%) | 0.16 |

| Others | 11 (8.4%) | 8 (15.4%) | 3 (3.8%) | 0.026 |

| Parameter * | IL-6 pg/mL 1 | PCT ng/mL 2 | Ferritin ng/mL 3 | CRP mg/L 4 | LDH IU/L 5 | Albumins g/L 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | 28.3 (7.67–105.37) | 0.61 (0.09–1.97) | 120 (53–252) | 20.56 (1.9–90.67) | 299 (233.5–370.25) | 30.47 (4.37) |

| Renal | 99.98 (9.74–637.55) | 100 (18.99–100) | 71 (35–1769) | 119.83 (21.18–175.69) | 229 (201.25–928) | 26 (4.39) |

| Neurological | 39.05 (13.96–147.3) | 38.91 (10.14–100) | 17,105 (5254–19,898) | 222.3 (4.07–247.67) | 928 (497–1229) | 24.91 (5.95) |

| Inflammatory | 12.7 (4.74–49.16) | 0.81 (0.14–2.79) | 396 (78.25–775.5) | 61.43 (24.027–183.78) | 270 (204.5–324) | 29.75 (5.07) |

| Haematological | 48.76 (22.98–249.85) | 0.3 (0.09–1.9) | 1517 (170.75–2816.75) | 31.72 (8.49–124.5) | 341.5 (271–459) | 27.94 (4.93) |

| Surgical | 25.53 (12.7–49.27) | 1.05 (0.07–5.48) | - | 68.45 (0.3–104.34) | 310 (268–341.5) | 24.62 (4.46) |

| Pulmonary | 76.63 (23.34–163.82) | 4.36 (0.97–19.99) | 194 (54–391) | 52.06 (29.89–260.37) | 493.5 (273.5–890) | 29.45 (4.39) |

| Others | 20.43 (5.59–200.6) | 5.42 (3.46–28.8) | 157 (115.5–216) | 130.35 (15.5–183.11) | 300 (215–521) | 26.16 (4.44) |

| p value | 0.045 * | 0.0001 * | 0.041 * | 0.243 * | 0.015 * | 0.011 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chisavu, F.; Chisavu, L.; Gafencu, M.; Hanu, D.; Steflea, R.M.; Bizerea-Moga, T.O.; Stroescu, R. The Prognostic Value of Inflammatory Markers in Paediatric Acute Kidney Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031099

Chisavu F, Chisavu L, Gafencu M, Hanu D, Steflea RM, Bizerea-Moga TO, Stroescu R. The Prognostic Value of Inflammatory Markers in Paediatric Acute Kidney Injury. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031099

Chicago/Turabian StyleChisavu, Flavia, Lazar Chisavu, Mihai Gafencu, Diana Hanu, Ruxandra Maria Steflea, Teofana Otilia Bizerea-Moga, and Ramona Stroescu. 2026. "The Prognostic Value of Inflammatory Markers in Paediatric Acute Kidney Injury" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031099

APA StyleChisavu, F., Chisavu, L., Gafencu, M., Hanu, D., Steflea, R. M., Bizerea-Moga, T. O., & Stroescu, R. (2026). The Prognostic Value of Inflammatory Markers in Paediatric Acute Kidney Injury. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031099