Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalized Cancer Patients: Single-Centre Real-Life Analysis of Incidence and Clinical Impact

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients’ Enrolment

2.2. Data Collection and Definition

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics

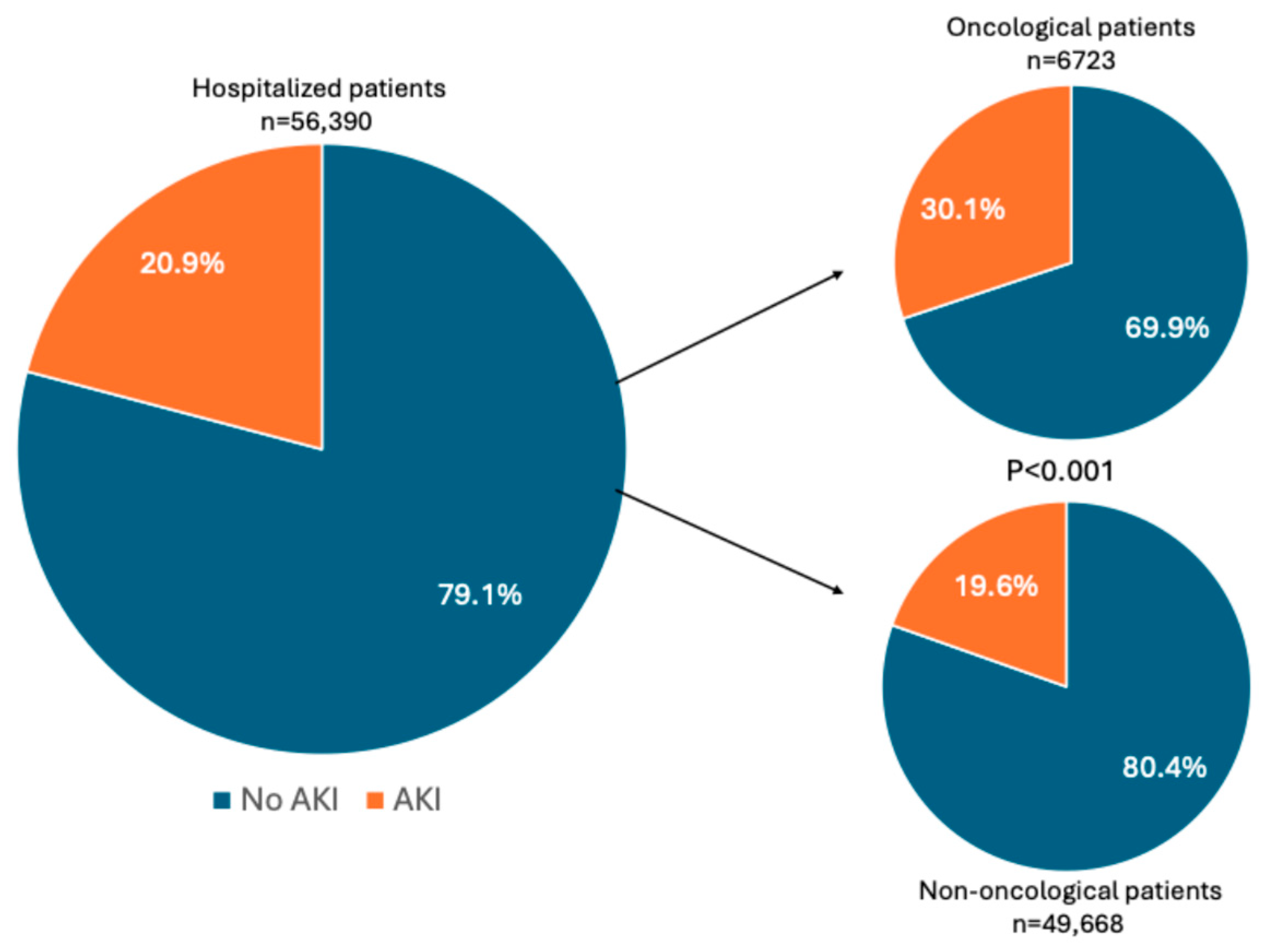

3.2. AKI Incidence and Staging

3.3. AKI Risk Factors in Oncological and Non-Oncological Populations

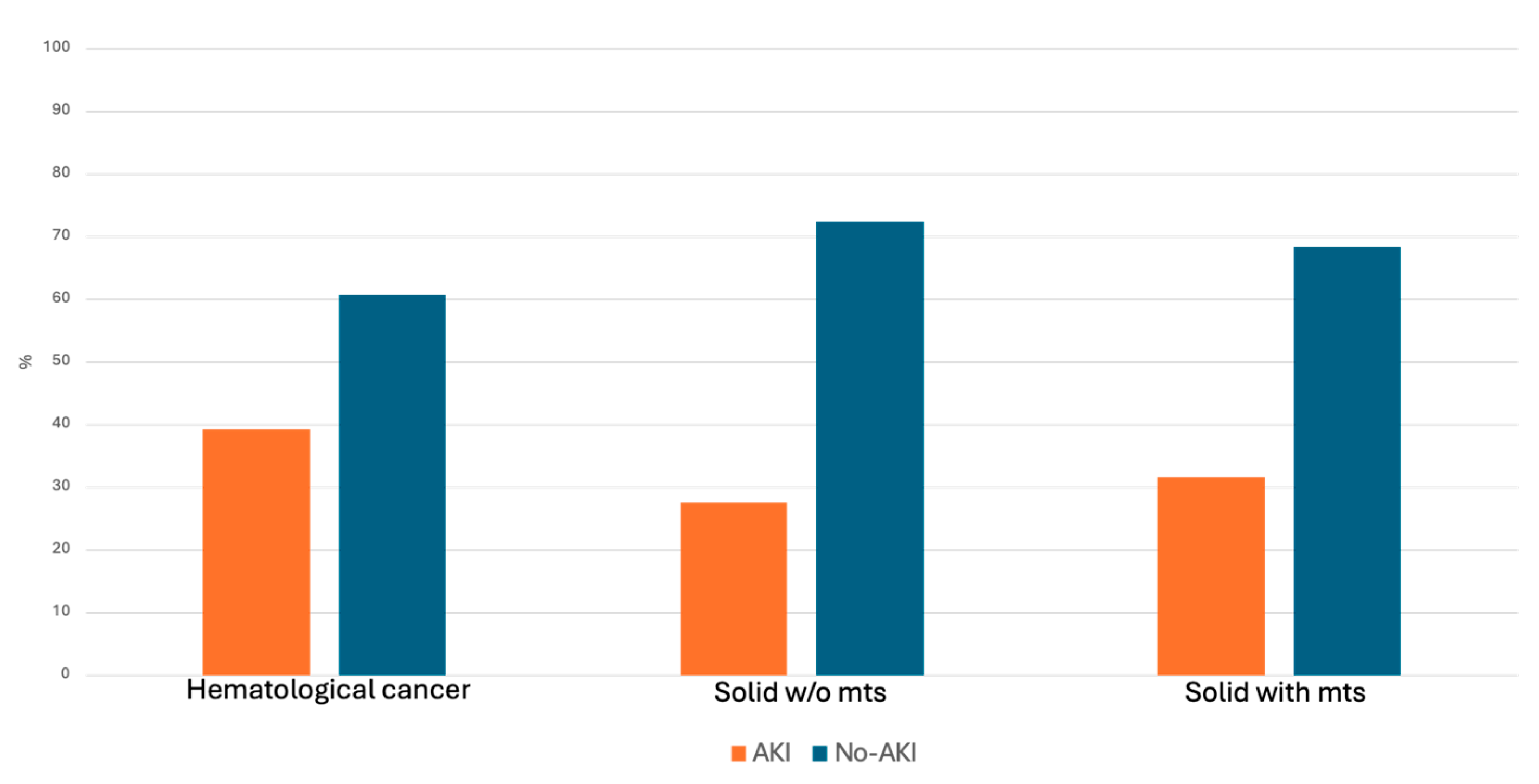

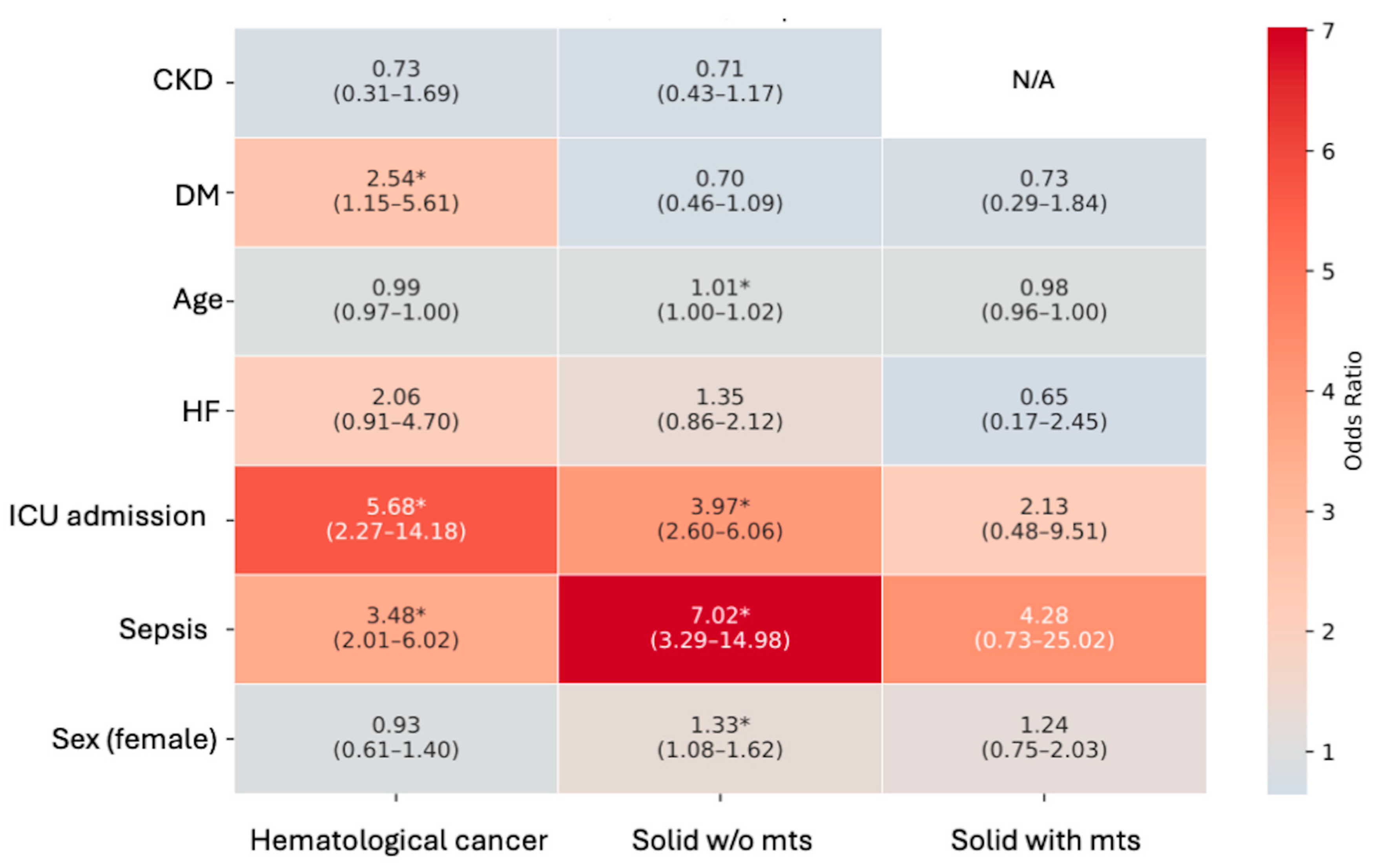

3.4. AKI Risk Factors in Oncological Subgroups

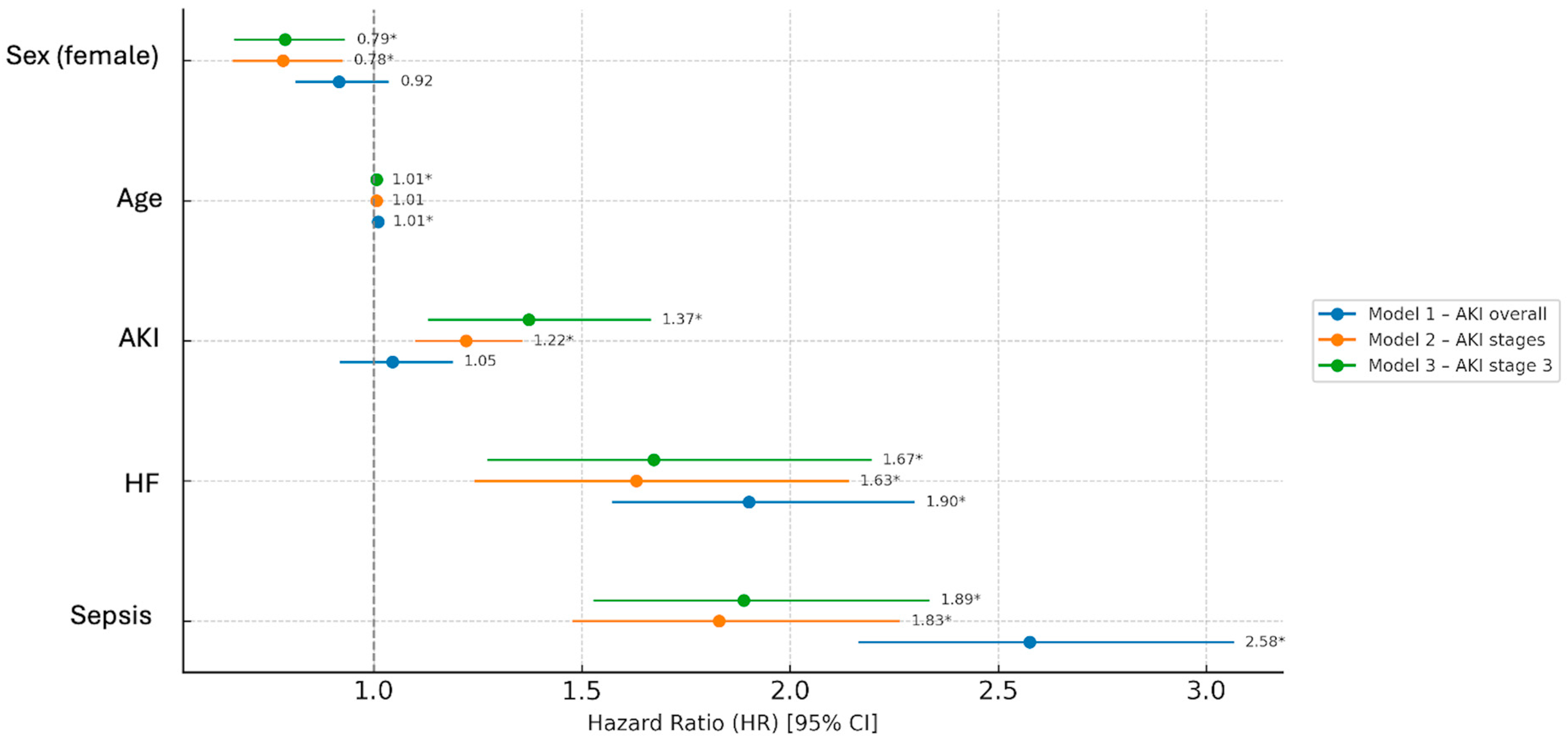

3.5. Outcomes and Associations with AKI Development

3.6. Outcomes in Oncological Patients’ Subgroups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| ER | Emergency room |

| HDF | Hospital discharge form |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| ICD-9-CM | International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| KDIGO | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes |

| LOS | Length of hospital stay |

| MTS | Metastases |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| sCr | Serum creatinine |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Floris, M.; Trevisani, F.; Angioi, A.; Lepori, N.; Simeoni, M.; Cabiddu, G.; Pani, A.; Rosner, M.H. Acute Kidney Disease in Oncology: A New Concept to Enhance the Understanding of the Impact of Kidney Injury in Patients with Cancer. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2024, 49, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchlu, A.; McArthur, E.; Amir, E.; Booth, C.M.; Sutradhar, R.; Majeed, H.; Nash, D.M.; Silver, S.A.; Garg, A.X.; Chan, C.T.; et al. Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Receiving Systemic Treatment for Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, P.; Bottini, A.; Lecini, E.; Cappadona, F.; Piaggio, M.; Macciò, L.; Genova, C.; Viazzi, F. Biopsy-Proven Acute Tubulointerstitial Nephritis in Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Pooled Analysis of Case Reports. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1221135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallieni, M.; Cosmai, L.; Porta, C. Acute Kidney Injury in Cancer Patients. Contrib. Nephrol. 2018, 193, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.; Gambella, M.; Raiola, A.M.; Beltrametti, E.; Zanetti, V.; Chirco, G.; Viazzi, F.; Angelucci, E.; Esposito, P. Acute Kidney Injury in Hematological Patients Treated with CAR-T Cells: Risk Factors, Clinical Presentation and Impact on Outcomes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Andes, L.J.; Koyama, A.K.; Xu, F.; Pavkov, M.E. Association Between Cancer and Incident Acute Kidney Injury Among Medicare Fee-for-Service Population. Kidney Med. 2025, 7, 101069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, G.A.; Hu, D.; Okusa, M.D. Acute Kidney Injury in the Cancer Patient. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014, 21, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, C.F.; Johansen, M.B.; Langeberg, W.J.; Fryzek, J.P.; Sørensen, H.T. Incidence of Acute Kidney Injury in Cancer Patients: A Danish Population-Based Cohort Study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 22, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosner, M.H.; Perazella, M.A. Acute Kidney Injury in Patients with Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1770–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Wang, L.; Su, L.; Luo, W.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Nie, S.; Hou, F.F. Acute Kidney Injury among Hospitalized Children with Cancer. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2021, 36, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellum, J.A.; Lameire, N. Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management of Acute Kidney Injury: A KDIGO Summary (Part 1). Crit. Care 2013, 17, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.D.; Goldstein, S.L.; Vijayan, A.; Parikh, C.R.; Kashani, K.; Okusa, M.D.; Agarwal, A.; Cerdá, J. AKI!Now Initiative: Recommendations for Awareness, Recognition, and Management of AKI. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 15, 1838–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, C.; Bellomo, R.; Kellum, J.A. Acute Kidney Injury. Lancet 2019, 394, 1949–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thau, M.R.; Bhatraju, P.K. Sub-Phenotypes of Acute Kidney Injury: Do We Have Progress for Personalizing Care? Nephron 2020, 144, 677–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, P.; Cappadona, F.; Prenna, S.; Marengo, M.; Fiorentino, M.; Fabbrini, P.; Quercia, A.D.; Naso, E.; Garzotto, F.; Russo, E.; et al. Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalized Patients with Real-Life Analysis of Incidence and Clinical Impact in Italian Hospitals (the SIN-AKI Study). Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2012, 2, 4. [CrossRef]

- Salahudeen, A.K.; Doshi, S.M.; Pawar, T.; Nowshad, G.; Lahoti, A.; Shah, P. Incidence Rate, Clinical Correlates, and Outcomes of AKI in Patients Admitted to a Comprehensive Cancer Center. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 8, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudsoorkar, P.; Langote, A.; Vaidya, P.; Meraz-Muñoz, A.Y. Acute Kidney Injury in Patients with Cancer: A Review of Onconephrology. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2021, 28, 394–401.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calças Marques, R.; Reis, M.; Pimenta, G.; Sala, I.; Chuva, T.; Coelho, I.; Ferreira, H.; Paiva, A.; Costa, J.M. Severe Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalized Cancer Patients: Epidemiology and Predictive Model of Renal Replacement Therapy and In-Hospital Mortality. Cancers 2024, 16, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmon, M.; Vincent, F.; Canet, E.; Mokart, D.; Pène, F.; Kouatchet, A.; Mayaux, J.; Nyunga, M.; Bruneel, F.; Rabbat, A.; et al. Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill Patients with Haematological Malignancies: Results of a Multicentre Cohort Study from the Groupe de Recherche En Réanimation Respiratoire En Onco-Hématologie. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, 2006–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameire, N.; Vanholder, R.; Van Biesen, W.; Benoit, D. Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill Cancer Patients: An Update. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbock, A.; Nadim, M.K.; Pickkers, P.; Gomez, H.; Bell, S.; Joannidis, M.; Kashani, K.; Koyner, J.L.; Pannu, N.; Meersch, M.; et al. Sepsis-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: Consensus Report of the 28th Acute Disease Quality Initiative Workgroup. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2023, 19, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, C.; Zhu, C.; Hu, S.; Mei, Y.; Yang, T. A Study on the Factors Influencing Mortality Risk in Sepsis-Induced Acute Kidney Injury Based on Analysis of the MIMIC Database. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 25, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soranno, D.E.; Awdishu, L.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Basile, D.; Bell, S.; Bihorac, A.; Bonventre, J.; Brendolan, A.; Claure-Del Granado, R.; Collister, D.; et al. The Role of Sex and Gender in Acute Kidney Injury—Consensus Statements from the 33rd Acute Disease Quality Initiative. Kidney Int. 2025, 107, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Hao, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, W.; Yu, F.; Hu, W.; Liang, X. Clinical Features, Risk Factors, and Clinical Burden of Acute Kidney Injury in Older Adults. Ren. Fail. 2020, 42, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booke, H.; von Groote, T.; Zarbock, A. Ten Tips on How to Reduce Iatrogenic Acute Kidney Injury. Clin. Kidney J. 2025, 18, sfae412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, M.H.; Perazella, M.A. Acute Kidney Injury in the Patient with Cancer. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 38, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmai, L.; Porta, C.; Foramitti, M.; Perrone, V.; Mollica, L.; Gallieni, M.; Capasso, G.; Clinici, I.; Maugeri, S. Preventive Strategies for Acute Kidney Injury in Cancer Patients. Clin. Kidney J. 2021, 14, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habas, E.; Akbar, R.; Farfar, K.; Arrayes, N.; Habas, A.; Rayani, A.; Alfitori, G.; Habas, E.; Magassabi, Y.; Ghazouani, H.; et al. Malignancy Diseases and Kidneys: A Nephrologist Prospect and Updated Review. Medicine 2023, 102, e33505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazella, M.A. Drug-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2019, 25, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Kang, E.; Kim, J.E.; Kang, U.; Kang, H.G.; Park, M.; Kim, K.; Kim, D.K.; Joo, K.W.; Kim, Y.S.; et al. Clinical Significance of Acute Kidney Injury in Lung Cancer Patients. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 53, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoste, E.A.J.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Bellomo, R.; Cely, C.M.; Colman, R.; Cruz, D.N.; Edipidis, K.; Forni, L.G.; Gomersall, C.D.; Govil, D.; et al. Epidemiology of Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill Patients: The Multinational AKI-EPI Study. Intensive Care Med. 2015, 41, 1411–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, M.A.; Weinberg, J.M.; Kriz, W.; Bidani, A.K. Failed Tubule Recovery, AKI-CKD Transition, and Kidney Disease Progression. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, K.; Deng, D.; Lin, C.; Wang, M.; Hsu, M.L.; Zaorsky, N.G. Causes of Death among People Living with Metastatic Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canet, E.; Zafrani, L.; Lambert, J.; Thieblemont, C.; Galicier, L.; Schnell, D.; Raffoux, E.; Lengline, E.; Chevret, S.; Darmon, M.; et al. Acute Kidney Injury in Patients with Newly Diagnosed High-Grade Hematological Malignancies: Impact on Remission and Survival. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Di Lauro, M.; Mitterhofer, A.P.; Ceravolo, M.J.; Di Daniele, N.; Manenti, G.; De Lorenzo, A. The Onco-Nephrology Field: The Role of Personalized Chemotherapy to Prevent Kidney Damage. Cancers 2023, 15, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, A.; Benigni, A.; Capitanio, U.; Danesh, F.R.; Di Marzo, V.; Gesualdo, L.; Grandaliano, G.; Jaimes, E.A.; Malyszko, J.; Perazella, M.A.; et al. Summary of the International Conference on Onco-Nephrology: An Emerging Field in Medicine. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xing, G.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Xu, G.; He, Q.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.; Liu, X.; et al. Acute Kidney Injury in China: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Lancet 2015, 386, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budczies, J.; von Winterfeld, M.; Klauschen, F.; Bockmayr, M.; Lennerz, J.K.; Denkert, C.; Wolf, T.; Warth, A.; Dietel, M.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; et al. The Landscape of Metastatic Progression Patterns across Major Human Cancers. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzedine, H.; Perazella, M.A. Anticancer Drug-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int. Rep. 2017, 2, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Oncological Patients | Non-Oncological Patients | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N. of subjects, n (%) | 6723 (11.9) | 49,668 (88.1) | |

| Age (years) | 73 ± 12.3 | 69.7 ± 19.4 | <0.001 |

| Sex M | 3780 (56.2) | 23,190 (46.7) | |

| F | 2943 (43.7) | 26,478 (53.3) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| DM | 602 (8.9) | 4247 (8.5) | 0.254 |

| CKD | 422 (6.3) | 4088 (8.2) | <0.001 |

| HF | 343 (5.5) | 4833 (9.7) | <0.001 |

| sCr admission (mg/dL) | 1.21 ± 1.05 | 1.13 ± 0.86 | <0.001 |

| Admission ward, n (%) | |||

| Medical unit | 1366 (20.3) | 10,937 (22) | |

| Surgery | 743 (11.05) | 9362 (18.8) | |

| ICU | 89 (1.3) | 2747 (5.5) | |

| ER | 4525 (67.3) | 26,622 (53.6) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 315 (4.7) | 2761 (5.6) | 0.003 |

| Oncological Population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haematological Cancer | Solid Cancer Without mts | Solid Cancer with mts | p | |

| N. of subjects, n (%) | 1107 (16.47) | 4767 (70.90) | 849 (12.63) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 73.9 ± 11.8 | 73.1 ± 12.5 | 71.4 ± 11.7 | 0.006 |

| Sex M | 603 (54.47) | 2745 (57.58) | 433 (51.00) | |

| F | 504 (45.53) | 2022 (42.42) | 416 (49.00) | 0.001 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| DM | 86 (7.8) | 446 (9.3) | 71 (8.3) | 0.199 |

| CKD | 107 (9.6) | 292 (6.1) | 23 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| HF | 69 (6.3) | 318 (6.7) | 29 (3.4) | 0.001 |

| SCr admission (mg/dL) | 1.39 ± 1.21 | 1.21 ± 1.05 | 1.06 ± 0.71 | <0.001 |

| Admission ward, n (%) | ||||

| Medical unit | 297 (26.83) | 889 (18.64) | 180 (21.22) | |

| Surgery | 52 (4.74) | 630 (13.22) | 61 (7.15) | |

| ICU | 17 (1.52) | 67 (1.40) | 6 (0.70) | |

| ER | 741 (66.91) | 3181 (66.74) | 602 (70.93) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 216 (19.5) | 89 (1.86) | 14 (1.17) | <0.001 |

| Oncological Patients | Non-Oncological Patients | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N. of subjects, n (%) | 6723 | 49,668 | |

| AKI, n (%) | 2022 (30.1) | 9749 (19.6) | <0.001 |

| Stage 1 | 1155 (57.1) | 5648 (57.9) | |

| Stage 2 | 535 (26.4) | 2672 (27.4) | |

| Stage 3 | 332 (16.4) | 1429 (14.6) | 0.12 |

| Only AKI stage 3 | - | - | 0.04 |

| Haematological Cancer | Solid Cancer Without mts | Solid Cancer with mts | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of subjects, n (%) | 1107 | 4767 | 849 | |

| AKI, n (%) | 435 (39.3) | 1318 (27.6) | 269 (31.7) | <0.001 |

| Stage 1 | 237 (54.6) | 769 (58.3) | 149 (55.4) | |

| Stage 2 | 126 (28.9) | 331 (25.1) | 78 (29) | |

| Stage 3 | 72 (16.5) | 218 (16.5) | 42 (15.6) | 0.444 |

| Only AKI stage 3 | - | - | - | 0.028 |

| Oncological AKI | Non-Oncological AKI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p | |

| Sex (female) | 1.23 | 1.04–1.4 | 0.014 | 1.21 | 1.13–1.3 | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.004 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.184 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.03 | <0.001 |

| CKD | 0.66 | 0.43–0.99 | 0.050 | 0.82 | 0.72–0.95 | 0.01 |

| HF | 1.39 | 0.9–2 | 0.076 | 1.59 | 1.38–1.75 | <0.001 |

| DM | 0.89 | 0.6–1.2 | 0.502 | 0.87 | 0.76–1.002 | 0.05 |

| Sepsis | 4.96 | 3.3–7.4 | <0.001 | 5.27 | 4.6–6.04 | <0.001 |

| ICU | 3.89 | 2.7–5.6 | <0.001 | 5.96 | 5.47–6.48 | <0.001 |

| Oncological | Non-Oncological | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N. | 6723 | 49,668 | |

| Mortality, n (%) | 1110 (16.52) | 3581 (7.21) | <0.001 |

| LOS (days) | 12 (7–21) | 8 (4–15) | <0.001 |

| LOS ≥ 15 days, n (%) | 2842 (42.3) | 12,541 (25.2) | <0.001 |

| sCr at discharge (mg/dL) | 1.14 ± 0.90 | 1.07 ± 0.75 | <0.001 |

| Mortality Risk in Non-Oncological Patients | ||||||

| Variable | Univariate HR | CI | p | Multivariate HR | CI | p |

| Sex (female) | 0.96 | 0.90–1.02 | 0.21 | 0.79 | 0.74–0.85 | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.02 | 1.01–1.02 | <0.001 | 1.01 | 1.01–1.02 | <0.001 |

| AKI | 2.12 | 1.90–2.35 | <0.001 | 1.52 | 1.39–1.65 | <0.001 |

| HF | 2.36 | 2.04–4.79 | <0.001 | 2.10 | 1.61–2.73 | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 4.45 | 3.59–5.42 | <0.001 | 3.68 | 3.41–3.97 | <0.001 |

| Mortality Risk in Oncological Patients | ||||||

| Variable | Univariate HR | CI | p | Multivariate HR | CI | p |

| Sex (female) | 0.92 | 0.81–1.04 | 0.14 | 0.92 | 0.81–1.03 | 0.15 |

| Age | 1.01 | 1.01–1.02 | <0.001 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.01 | <0.001 |

| AKI | 1.18 | 1.03–1.36 | 0.01 | 1.06 | 0.92–1.19 | 0.49 |

| HF | 2.02 | 1.24–4.01 | <0.001 | 1.90 | 1.57–2.27 | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 2.64 | 2.14–3.30 | <0.001 | 2.58 | 2.17–3.06 | <0.001 |

| Haematological Cancer | Solid Cancer Without mts | Solid Cancer with mts | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. | 1107 | 4767 | 849 | |

| Mortality, n (%) | 209 (18.9) | 706 (14.89) | 195 (22.9) | <0.001 |

| LOS (days) | 14 (8–24) | 12 (7–20) | 12 (8–19) | <0.001 |

| LOS ≥ 15 days, n (%) | 540 (48.7) | 1953 (40.9) | 349 (41.1) | <0.001 |

| sCr at discharge (mg/dL) | 1.31 ± 1.08 | 1.12 ± 0.84 | 1.06 ± 0.90 | <0.001 |

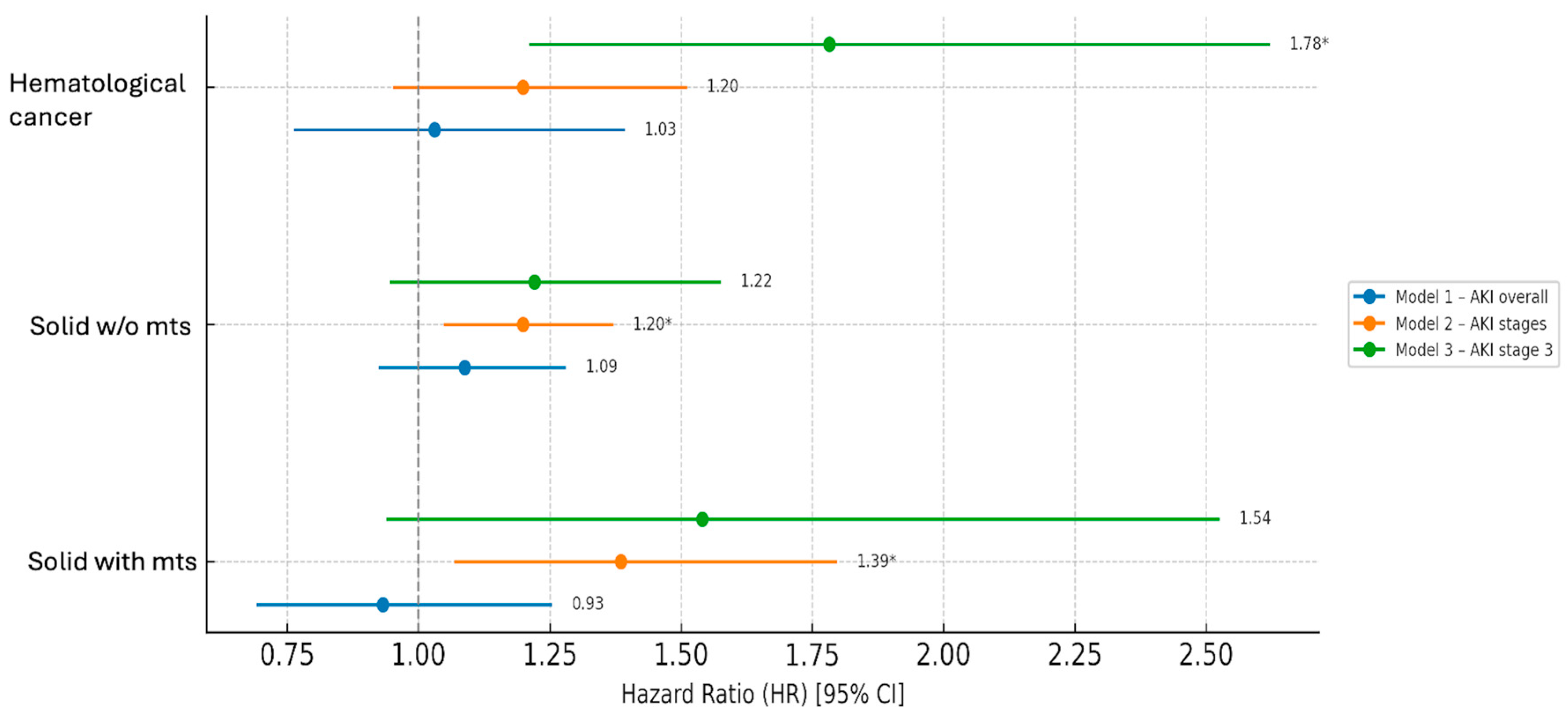

| Hematological Cancer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Sex (F vs. M) HR (95% CI) | Age | AKI | Heart Failure | Sepsis |

| Model 1—AKI overall | 0.87 (0.66–1.14) | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | 1.03 (0.76–1.39) | 1.38 (0.91–2.08) | 2.63 (1.97–3.51) § |

| Model 2—AKI stages | 0.67 (0.48–0.95) * | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) § | 1.20 (0.95–1.51) | 1.31 (0.78–2.19) | 1.89 (1.33–2.69) § |

| Model 3—AKI stage 3 | 0.66 (0.47–0.94) * | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) § | 1.78 (1.21–2.62) § | 1.39 (0.83–2.31) | 1.96 (1.38–2.78) § |

| Solid cancer without metastases | |||||

| Model | |||||

| Model 1—AKI overall | 0.90 (0.77–1.04) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) § | 1.09 (0.93–1.28) | 2.20 (1.76–2.77) § | 3.58 (2.76–4.64) § |

| Model 2—AKI stages | 0.82 (0.66–1.01) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.20 (1.05–1.37) * | 1.98 (1.41–2.77) § | 2.42 (1.78–3.29) § |

| Model 3—AKI stage 3 | 0.82 (0.67–1.02) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.22 (0.95–1.57) | 1.97 (1.41–2.75) § | 2.56 (1.89–3.47) § |

| Solid cancer with metastases | |||||

| Model | |||||

| Model 1—AKI overall | 1.04 (0.78–1.38) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.93 (0.69–1.25) | 3.79 (2.03–7.10) § | 2.55 (1.28–5.11) * |

| Model 2—AKI stages | 0.78 (0.51–1.19) | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 1.39 (1.07–1.80) * | 1.76 (0.53–5.86) | 0.99 (0.35–2.79) |

| Model 3—AKI stage 3 | 0.79 (0.52–1.20) | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 1.54 (0.94–2.52) | 1.93 (0.58–6.40) | 1.12 (0.40–3.14) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Esposito, P.; Cappadona, F.; Bottini, A.; Russo, E.; Garibotto, G.; Cantaluppi, V.; Viazzi, F. Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalized Cancer Patients: Single-Centre Real-Life Analysis of Incidence and Clinical Impact. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020690

Esposito P, Cappadona F, Bottini A, Russo E, Garibotto G, Cantaluppi V, Viazzi F. Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalized Cancer Patients: Single-Centre Real-Life Analysis of Incidence and Clinical Impact. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):690. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020690

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsposito, Pasquale, Francesca Cappadona, Annarita Bottini, Elisa Russo, Giacomo Garibotto, Vincenzo Cantaluppi, and Francesca Viazzi. 2026. "Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalized Cancer Patients: Single-Centre Real-Life Analysis of Incidence and Clinical Impact" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020690

APA StyleEsposito, P., Cappadona, F., Bottini, A., Russo, E., Garibotto, G., Cantaluppi, V., & Viazzi, F. (2026). Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalized Cancer Patients: Single-Centre Real-Life Analysis of Incidence and Clinical Impact. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020690