Cardiac Rehabilitation After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Physiology and Pathophysiology of LVAD at Rest and During Exercise

2.1. Determinant of Functional Capacity in LVAD Recipients

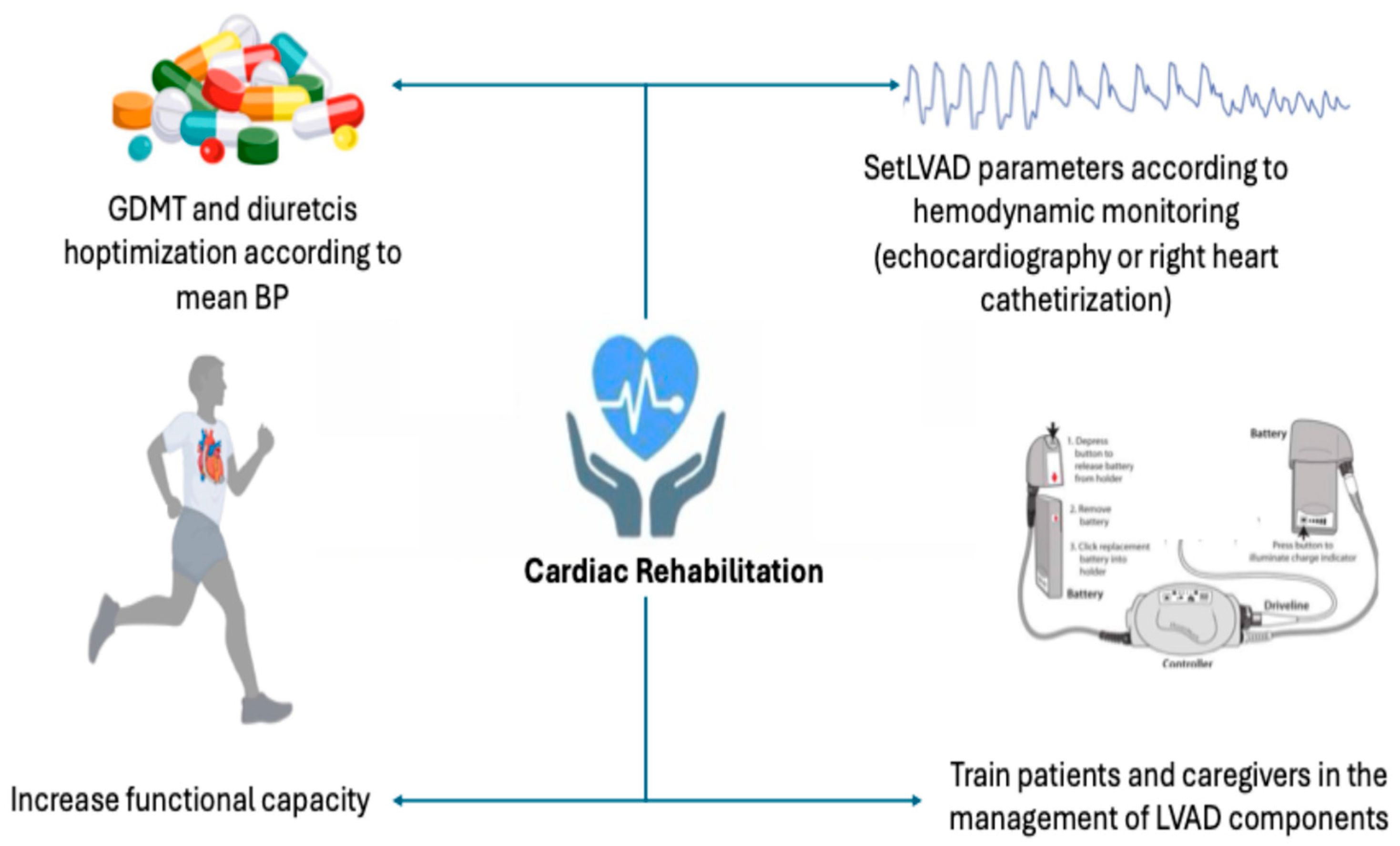

2.2. Effect of LVAD Implant on Functional Capacity

2.3. Role of the Right Ventricle

3. CR in Patients with HF: General Principles

4. CR Post LVAD Implant: Rationale and Results

5. Practical Aspect of CR After LVAD Implantation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Masarone, D.; Houston, B.; Falco, L.; Martucci, M.L.; Catapano, D.; Valente, F.; Gravino, R.; Contaldi, C.; Petraio, A.; De Feo, M.; et al. How to Select Patients for Left Ventricular Assist Devices? A Guide for Clinical Practice. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, A.; Cascino, T.M.; DeFilippis, E.M.; Hanff, T.C.; Cevasco, M.; Keenan, J.; Tong, M.Z.-Y.; Kilic, A.; Koehl, D.; Cantor, R.; et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs 2025 Annual Report: Focus on Outcomes in Older Adults. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2025, 121, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, B.; Fonarow, G.C.; Goldberg, L.R.; Guglin, M.; Josephson, R.A.; Forman, D.E.; Lin, G.; Lindenfeld, J.; O’Connor, C.; Panjrath, G.; et al. ACC’s Heart Failure and Transplant Section and Leadership Council. Cardiac Rehabilitation for Patients With Heart Failure: JACC Expert Panel. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1454–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moctezuma-Ramirez, A.; Mohammed, H.; Hughes, A.; Elgalad, A. Recent Developments in Ventricular Assist Device Therapy. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 26, 25440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkin, M.N.; Kagan, V.; Labuhn, C.; Pinney, S.P.; Grinstein, J. Physiology and Clinical Utility of HeartMate Pump Parameters. J. Card. Fail. 2022, 28, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, S.; Bonios, M.; Ben Gal, T.; Gustafsson, F.; Abdelhamid, M.; Adamo, M.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Böhm, M.; Chioncel, O.; Cohen-Solal, A.; et al. Right heart failure with left ventricular assist devices: Preoperative, perioperative and postoperative management strategies. A clinical consensus statement of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 2304–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fresiello, L.; Gross, C.; Jacobs, S. Exercise physiology in left ventricular assist device patients: Insights from hemodynamic simulations. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 10, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupper, A.; Mazin, I.; Faierstein, K.; Kurnick, A.; Maor, E.; Elian, D.; Barbash, I.M.; Guetta, V.; Regev, E.; Morgan, A.; et al. Hemodynamic Changes After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation Among Heart Failure Patients With and Without Elevated Pulmonary Vascular Resistance. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 875204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, C.; Marko, C.; Mikl, J.; Altenberger, J.; Schlöglhofer, T.; Schima, H.; Zimpfer, D.; Moscato, F. LVAD Pump Flow Does Not Adequately Increase With Exercise. Artif. Organs 2019, 43, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.H.; Hansen, P.B.; Sander, K.; Olsen, P.S.; Rossing, K.; Boesgaard, S.; Russell, S.D.; Gustafsson, F. Effect of increasing pump speed during exercise on peak oxygen uptake in heart failure patients supported with a continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. A double-blind randomized study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014, 16, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camboni, D.; Lange, T.J.; Ganslmeier, P.; Hirt, S.; Flörchinger, B.; Zausig, Y.; Rupprecht, L.; Hilker, M.; Schmid, C. Left ventricular support adjustment to aortic valve opening with analysis of exercise capacity. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2014, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, M.R.; Bowles, C.; Banner, N.R. Relationship between pump speed and exercise capacity during HeartMate II left ventricular assist device support: Influence of residual left ventricular function. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2012, 14, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, N.; Rakita, V.; Lala, A.; Parikh, A.; Roldan, J.; Mitter, S.S.; Anyanwu, A.; Campoli, M.; Burkhoff, D.; Mancini, D.M. Hemodynamic Response to Exercise in Patients Supported by Continuous Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices. JACC Heart Fail. 2020, 8, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlay, S.M.; Allison, T.G.; Pereira, N.L. Changes in cardiopulmonary exercise testing parameters following continuous flow left ventricular assist device implantation and heart transplantation. J. Card. Fail. 2014, 20, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, S.E.A.; Oerlemans, M.I.F.; Ramjankhan, F.Z.; Muller, S.A.; Kirkels, H.H.; van Laake, L.W.; Suyker, W.J.L.; Asselbergs, F.W.; de Jonge, N. One year improvement of exercise capacity in patients with mechanical circulatory support as bridge to transplantation. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 1796–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresiello, L.; Jacobs, S.; Timmermans, P.; Buys, R.; Hornikx, M.; Goetschalckx, K.; Droogne, W.; Meyns, B. Limiting factors of peak and submaximal exercise capacity in LVAD patients. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezzani, A.; Pistonoa, M.; Corrà, U. Systemic perfusion at peak incremental exercise in left ventricular assist device recipients: Partitioning pump and native left ventricle relative contribution. IJC Heart Vessel. 2014, 4, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Needs and Action Priorities in Cardiac Rehabilitation and Secondary Prevention in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.S.; Dalal, H.M.; Zwisler, A.D. Cardiac rehabilitation for heart failure: ‘Cinderella’ or evidence-based pillar of care? Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 1511–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.M.; Pack, Q.R.; Aberegg, E.; Brewer, L.C.; Ford, Y.R.; Forman, D.E.; Gathright, E.C.; Khadanga, S.; Ozemek, C.; Thomas, R.J.; et al. Core Components of Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs: 2024 Update: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Circulation 2024, 150, e328–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damluji, A.A.; Tomczak, C.R.; Hiser, S.; O’Neill, D.E.; Goyal, P.; Pack, Q.R.; Foulkes, S.J.; Brown, T.M.; Haykowsky, M.J.; Needham, D.M.; et al. Benefits of Cardiac Rehabilitation: Mechanisms to Restore Function and Clinical Impact. Circ. Res. 2025, 137, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molloy, C.; Long, L.; Mordi, I.R.; Bridges, C.; Sagar, V.A.; Davies, E.J.; Coats, A.J.; Dalal, H.; Rees, K.; Singh, S.J.; et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 3, CD003331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.S.; Walker, S.; Ciani, O.; Warren, F.; Smart, N.A.; Piepoli, M.; Davos, C.H. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for chronic heart failure: The EXTRAMATCH II individual participant data meta-analysis. Health Technol. Assess. 2019, 23, 1–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, E.; Brailovsky, Y.; Rajapreyar, I. Exercise and cardiac rehabilitation after LVAD implantation. Heart Fail. Rev. 2025, 30, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsara, O.; Reeves, R.K.; Pyfferoen, M.D.; Trenary, T.L.; Engen, D.J.; Vitse, M.L.; Kessler, S.M.; Kushwaha, S.S.; Clavell, A.L.; Thomas, R.J.; et al. Inpatient rehabilitation outcomes for patients receiving left ventricular assist device. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 93, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, T.A.; Martin, D.P.; Stolov, W.C.; Deyo, R.A. A validation of the functional independence measurement and its performance among rehabilitation inpatients. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1993, 74, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, G.; Coyle, L.; Milkevitch, K.; Adair, R.; Tatooles, A.; Bhat, G. Efficacy of Inpatient Rehabilitation After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation. PM&R 2017, 9, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nora, C.; Guidetti, F.; Livi, U.; Antonini-Canterin, F. Role of Cardiac Rehabilitation After Ventricular Assist Device Implantation. Heart Fail. Clin. 2021, 17, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marko, C.; Danzinger, G.; Käferbäck, M.; Lackner, T.; Müller, R.; Zimpfer, D.; Schima, H.; Moscato, F. Safety and efficacy of cardiac rehabilitation for patients with continuous flow left ventricular assist devices. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2015, 22, 1378–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimopoulos, S.K.; Drakos, S.G.; Terrovitis, J.V.; Tzanis, G.S.; Nanas, S.N. Improvement in respiratory muscle dysfunction with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2010, 29, 906–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrigan, D.J.; Williams, C.T.; Ehrman, J.K.; Saval, M.A.; Bronsteen, K.; Schairer, J.R.; Swaffer, M.; Brawner, C.A.; Lanfear, D.E.; Selektor, Y.; et al. Cardiac rehabilitation improves functional capacity and patient-reported health status in patients with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices: The Rehab-VAD randomized controlled trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2014, 2, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaaban, A.; Schultz, J.; Leonard, J.; Martin, C.M.; Kamdar, F.; Alexy, T.; Thenappan, T.; Pritzker, M.; Shaffer, A.; John, R.; et al. Outcomes of Patients Referred for Cardiac Rehabilitation After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation. ASAIO J. 2023, 69, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, T.; Bjarnason-Wehrens, B.; Bartsch, P.; Deniz, E.; Schmitto, J.; Schulte-Eistrup, S.; Willemsen, D.; Reiss, N. Exercise capacity and functional performance in heart failure patients supported by a left ventricular assist device at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Artif. Organs 2018, 42, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaglione, A.; Panzarino, C.; Modica, M.; Tavanelli, M.; Pezzano, A.; Grati, P.; Racca, V.; Toccafondi, A.; Bordoni, B.; Verde, A.; et al. Short- and long-term effects of a cardiac rehabilitation program in patients implanted with a left ventricular assist device. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez Villela, M.; Chinnadurai, T.; Salkey, K.; Furlani, A.; Yanamandala, M.; Vukelic, S.; Sims, D.B.; Shin, J.J.; Saeed, O.; Jorde, U.P.; et al. Feasibility of high-intensity interval training in patients with left ventricular assist devices: A pilot study. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, M.L.; Speed, J. Effectiveness of acute inpatient rehabilitation after left ventricular assist device placement. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 92, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukamachi, K.; Shiose, A.; Massiello, A.; Horvath, D.J.; Golding, L.A.; Lee, S.; Starling, R.C. Preload sensitivity in cardiac assist devices. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 95, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troutman, G.S.; Genuardi, M.V. Left Ventricular Assist Devices: A Primer for the Non-Mechanical Circulatory Support Provider. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudim, M.; Rogers, J.G.; Frazier-Mills, C.; Patel, C.B. Orthostatic Hypotension in Patients With Left Ventricular Assist Devices: Acquired Autonomic Dysfunction. ASAIO J. 2018, 64, e40–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, R.L.; McCall, M.; Althouse, A.; Lagazzi, L.; Schaub, R.; Kormos, M.A.; Zaldonis, J.A.; Sciortino, C.; Lockard, K.; Kuntz, N.; et al. Left Ventricular Assist Device Malfunctions: It Is More Than Just the Pump. Circulation 2017, 136, 1714–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cardiac and LVAD Factors |

| Chronotropic incompetence |

| Right ventricular function and pulmonary pressure |

| Native left ventricular contractility |

| Native heart valvular diseases |

| LVAD sensitivity to afterload |

| Extracardiac factors |

| Anemia |

| Skeletal muscle abnormalities |

| Alteration in alveolar gas exchange |

| Hypertension induced by physical exercise |

| Physical deconditioning |

| Study | Numbers of Patients | Intervention Duration (Weeks) | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marko [29] | 41 | 5 | Improvement pVO2 |

| Kerrigan [31] | 26 | 6 | Improvement pVO2 |

| Schmidt [33] | 10 | 3 | Muscular strength in all trained muscles |

| Scaglione [34] | 25 | 4 | Improvement pVO2 |

| Alvarez Villela [35] | 12 | 5 | Improvement pVO2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gravino, R.; Falco, L.; Catapano, D.; Amarelli, C.; Valente, F.; Verrengia, M.; Marra, C.; Di Lorenzo, E.; Di Silverio, P.; Kittleson, M.; et al. Cardiac Rehabilitation After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031089

Gravino R, Falco L, Catapano D, Amarelli C, Valente F, Verrengia M, Marra C, Di Lorenzo E, Di Silverio P, Kittleson M, et al. Cardiac Rehabilitation After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031089

Chicago/Turabian StyleGravino, Rita, Luigi Falco, Dario Catapano, Cristiano Amarelli, Fabio Valente, Marina Verrengia, Claudio Marra, Emilio Di Lorenzo, Pierino Di Silverio, Michelle Kittleson, and et al. 2026. "Cardiac Rehabilitation After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: A Narrative Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031089

APA StyleGravino, R., Falco, L., Catapano, D., Amarelli, C., Valente, F., Verrengia, M., Marra, C., Di Lorenzo, E., Di Silverio, P., Kittleson, M., & Masarone, D. (2026). Cardiac Rehabilitation After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031089