Does Prolonged Preservation of Blastocysts Affect the Implantation and Live Birth Rate? A Danish Nationwide Register-Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

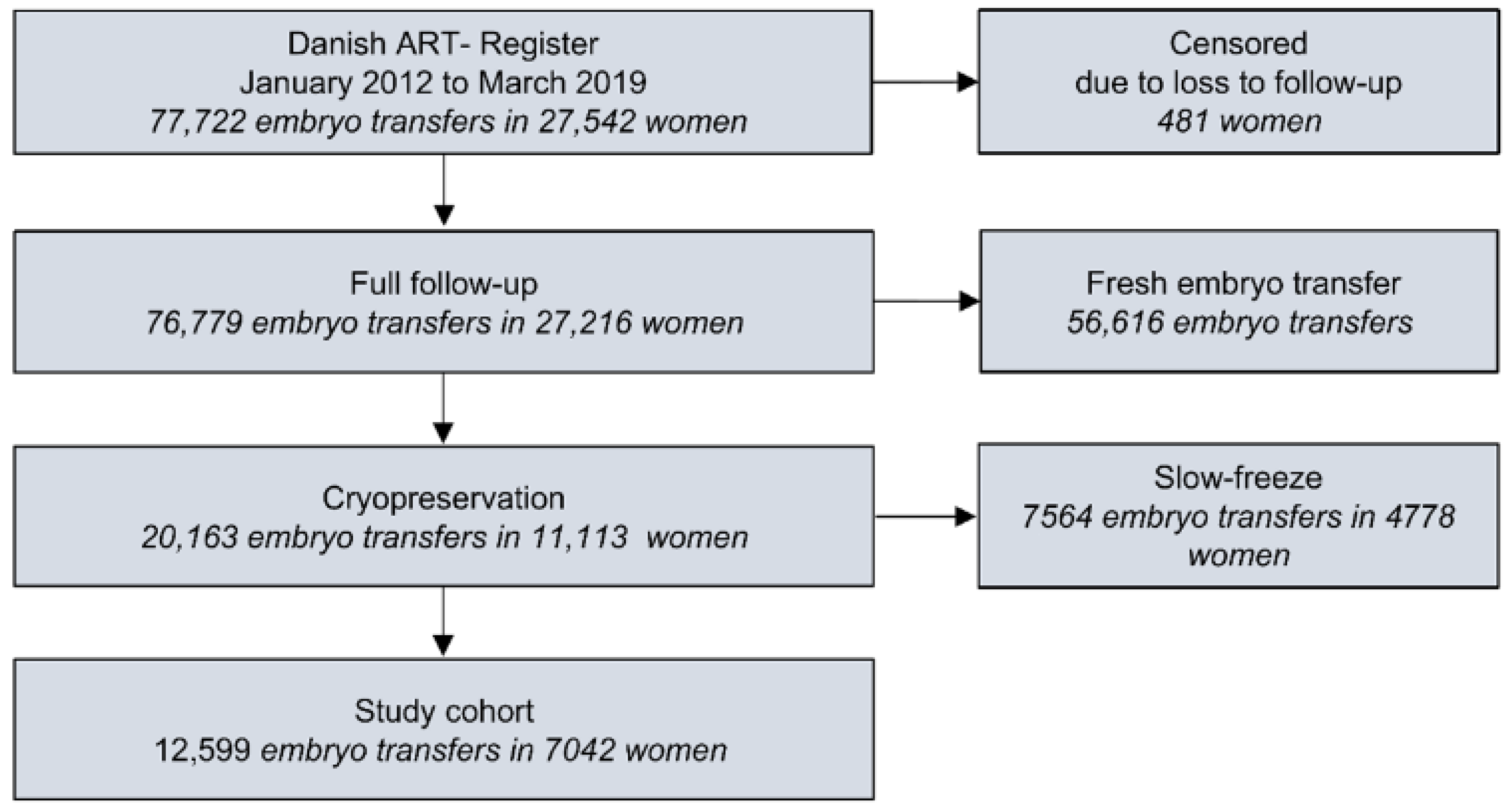

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. ART Procedures

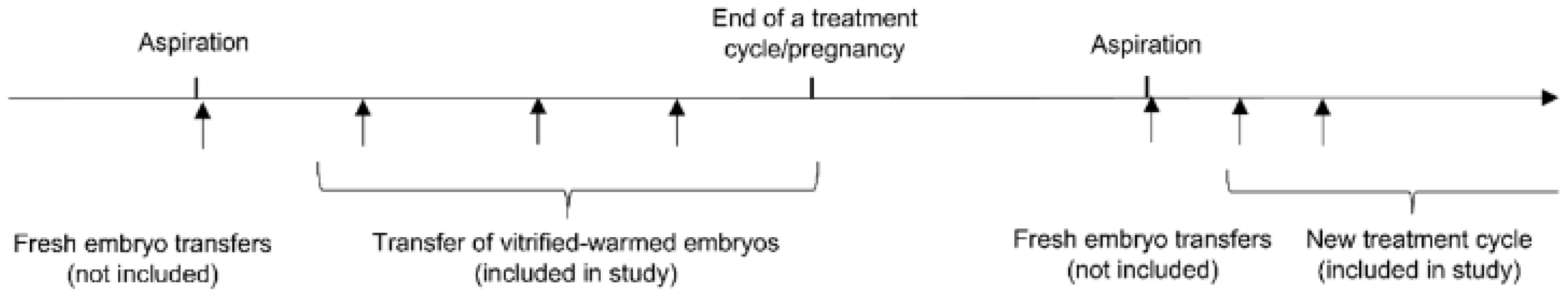

2.3. Study Design and Inclusion

2.4. Exposure and Clinical Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analyses and Possible Confounders

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics of the Cohort

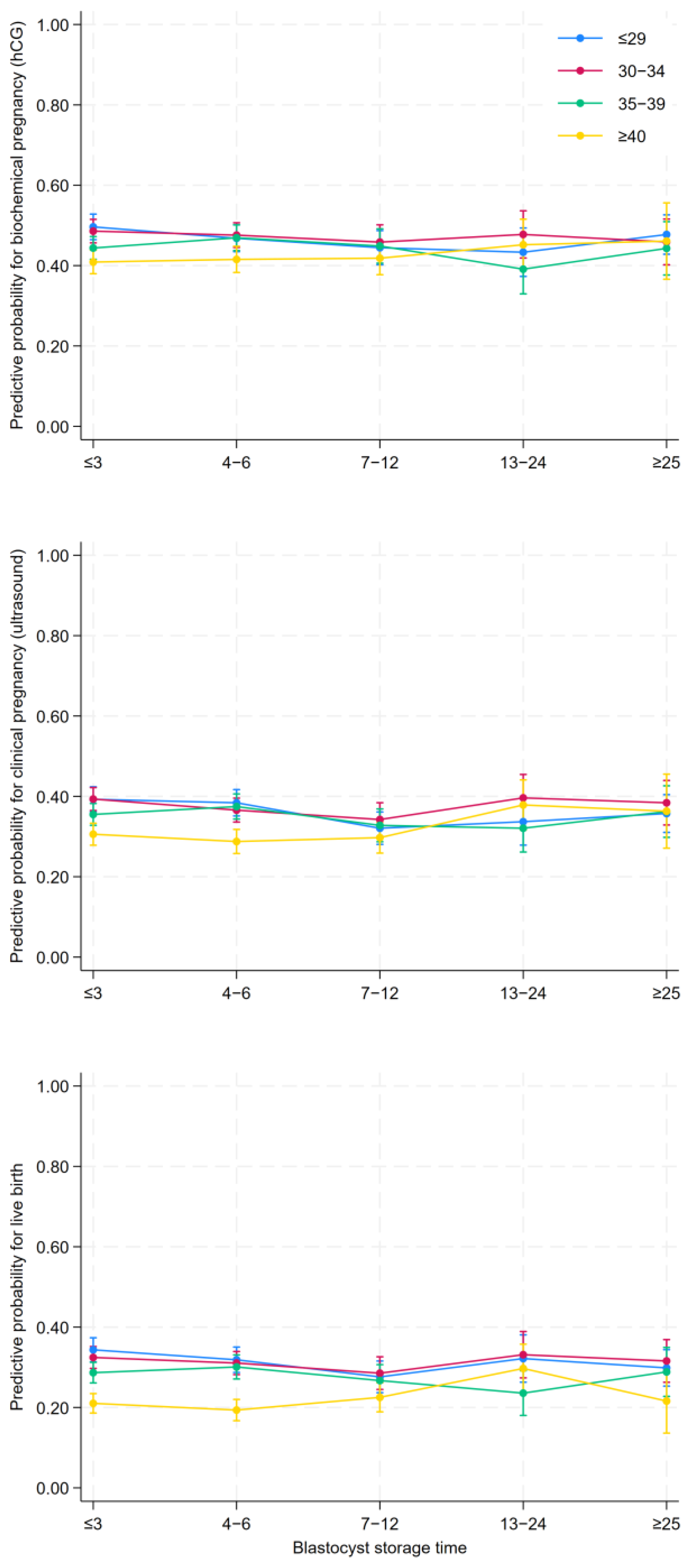

3.2. Clinical Results According to Blastocyst Storage Time

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Comparison with Previous Research

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ART | Assisted Reproductive Technology |

| FET | Frozen Embryo Transfers |

| LGA | Large for Gestational Age |

| SGA | Small for Gestational Age |

| OHSS | Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome |

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome |

| hCG | human Chorionic Gonadotropin |

| LN2 | Liquid Nitrogen |

| DNPR | Danish National Patient Register |

| DMBR | Danish Medical Birth Register |

Appendix A. ICD-10 Diagnoses of Congenital Malformation

| Q10–Q16 |

| Q20–Q28 |

| Q30–Q34 |

| Q35–Q37 |

| Q38–Q45 |

| Q50–Q56 |

| Q60–Q64 |

| Q65–Q79 |

| Q80–Q89 |

| Q90–Q99 |

References

- Trounson, A.; Mohr, L. Human pregnancy following cryopreservation, thawing and transfer of an eight-cell embryo. Nature 1983, 305, 707–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.A.; Waterstone, M.; Anastacio, A. Ice age: Cryopreservation in assisted reproduction—An update. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 19, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormlund, S.; Sopa, N.; Zedeler, A.; Bogstad, J.; Praetorius, L.; Nielsen, H.S.; Kitlinski, M.L.; Skouby, S.O.; Mikkelsen, A.L.; Spangmose, A.L.; et al. Freeze-all versus fresh blastocyst transfer strategy during in vitro fertilisation in women with regular menstrual cycles: Multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2020, 370, m2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devroey, P.; Polyzos, N.P.; Blockeel, C. An OHSS-Free Clinic by segmentation of IVF treatment. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 2593–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European IVF Monitoring Consortium (EIM), for the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE); Wyns, C.; De Geyter, C.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; Kupka, M.S.; Motrenko, T.; Smeenk, J.; Bergh, C.; Tandler-Schneider, A.; Rugescu, I.A.; et al. ART in Europe, 2018: Results generated from European registries by ESHRE. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienzi, L.; Gracia, C.; Maggiulli, R.; LaBarbera, A.R.; Kaser, D.J.; Ubaldi, F.M.; Vanderpoel, S.; Racowsky, C. Oocyte, embryo and blastocyst cryopreservation in ART: Systematic review and meta-analysis comparing slow-freezing versus vitrification to produce evidence for the development of global guidance. Hum. Reprod. Update 2017, 23, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirleitner, B.; Vanderzwalmen, P.; Bach, M.; Baramsai, B.; Neyer, A.; Schwerda, D.; Schuff, M.; Spitzer, D.; Stecher, A.; Zintz, M.; et al. The time aspect in storing vitrified blastocysts: Its impact on survival rate, implantation potential and babies born. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 2950–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, S.; Uchiyama, K.; Kuroda, T.; Yabuuchi, A.; Ezoe, K.; Okimura, T.; Okuno, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Kato, K. Cryostorage duration does not affect pregnancy and neonatal outcomes: A retrospective single-centre cohort study of vitrified-warmed blastocysts. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2018, 36, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Dong, X.; Lyu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Ai, J. The Impact of Embryo Storage Time on Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes and the Time Limit of Vitrification: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 724853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.; Zhou, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, H.; Shu, J.; Gan, X.; Xu, K.; Zhao, X. Does longer storage of blastocysts with equal grades in a cryopreserved state affect the perinatal outcomes? Cryobiology 2021, 103, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimadomo, D.; Fabozzi, G.; Dovere, L.; Maggiulli, R.; Albricci, L.; Innocenti, F.; Soscia, D.; Giancani, A.; Vaiarelli, A.; Guido, M.; et al. Clinical, obstetric and perinatal outcomes after vitrified-warmed euploid blastocyst transfer are independent of cryo-storage duration. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2022, 44, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guo, P.; Blockeel, C.; Li, X.; Deng, L.; Yang, J.; Li, C.; Lin, M.; Wu, H.; Cai, G.; et al. Storage duration of vitrified embryos does not affect pregnancy and neonatal outcomes after frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1148411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Sun, M.; Wen, T.; Ding, C.; Liu, L.W.; Meng, T.; Song, J.; Hou, X.; Mai, Q.; Xu, Y. Storage time does not influence pregnancy and neonatal outcomes for first single vitrified high-quality blastocyst transfer cycle. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2023, 47, 103254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssry, M.; Ozmen, B.; Zohni, K.; Diedrich, K.; Al-Hasani, S. Current aspects of blastocyst cryopreservation. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2008, 16, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lattes, K.; Checa, M.A.; Vassena, R.; Brassesco, M.; Vernaeve, V. There is no evidence that the time from egg retrieval to embryo transfer affects live birth rates in a freeze-all strategy. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malter, H. Life Interrupted: The Nature and Consequences of Cryostasis. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2018, 36, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canosa, S.; Cimadomo, D.; Conforti, A.; Maggiulli, R.; Giancani, A.; Tallarita, A.; Golia, F.; Fabozzi, G.; Vaiarelli, A.; Gennarelli, G.; et al. The effect of extended cryo-storage following vitrification on embryo competence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yin, M.; Wang, B.; Lin, J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, N.; Lyu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Zhu, Q. The effect of storage time after vitrification on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes among 24 698 patients following the first embryo transfer cycles. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 35, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, S.; Hao, G.; Wu, X.; Ren, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, A.; Bi, X.; Bai, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Prolonged Cryopreservation Negatively Affects Embryo Transfer Outcomes Following the Elective Freeze-All Strategy: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 709648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, K.L.; Hunt, S.; Zhang, D.; Li, R.; Mol, B.W. The association between embryo storage time and treatment success in women undergoing freeze-all embryo transfer. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 118, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Tang, N.; Luo, Y.; Yin, P.; Li, L. Effects of vitrified cryopreservation duration on IVF and neonatal outcomes. J. Ovarian Res. 2022, 15, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Mo, M.; Zhang, H.; Xu, S.; Xu, F.; Wang, S.; Zeng, Y. Prolong cryopreservation duration negatively affects pregnancy outcomes of vitrified-warmed blastocyst transfers using an open-device system: A retrospective cohort study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2023, 281, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S.; Lin, C.; Lin, Q.; Gan, J.; Wang, C.; Luo, Y.; Liu, J.; Du, H.; Liu, H. Vitrification preservation of good-quality blastocysts for more than 5 years reduces implantation and live birth rates. Hum. Reprod. 2024, 39, 1960–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Schmidt, S.A.; Sandegaard, J.L.; Ehrenstein, V.; Pedersen, L.; Sorensen, H.T. The Danish National Patient Registry: A review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin. Epidemiol. 2015, 7, 449–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.N.; Westergaard, H.B.; Olsen, J. The Danish in vitro fertilisation (IVF) register. Dan. Med. Bull. 1999, 46, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Westergaard, H.B.; Johansen, A.M.; Erb, K.; Andersen, A.N. Danish National IVF Registry 1994 and 1995. Treatment, pregnancy outcome and complications during pregnancy. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2000, 79, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolving, L.R.; Erb, K.; Norgard, B.M.; Fedder, J.; Larsen, M.D. The Danish National Register of assisted reproductive technology: Content and research potentials. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, J.; Langhoff-Roos, J.; Skovgaard, L.T.; Kristensen, F.B. Validation of the Danish Birth Registration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1996, 49, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliddal, M.; Broe, A.; Pottegard, A.; Olsen, J.; Langhoff-Roos, J. The Danish Medical Birth Register. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 33, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpha Scientists in Reproductive Medicine; ESHRE Special Interest Group of Embryology. The Istanbul consensus workshop on embryo assessment: Proceedings of an expert meeting. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 1270–1283. [CrossRef]

- Working Group on the Update of the ESHRE/ALPHA Istanbul Consensus; Coticchio, G.; Ahlstrom, A.; Arroyo, G.; Balaban, B.; Campbell, A.; De Los Santos, M.J.; Ebner, T.; Gardner, D.K.; Kovacic, B.; et al. The Istanbul consensus update: A revised ESHRE/ALPHA consensus on oocyte and embryo static and dynamic morphological assessmentdagger, double dagger. Hum. Reprod. 2025, 40, 989–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, T.; Chen, H.; Fu, R.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Mol, B.W.; Kuang, Y.; Lyu, Q. Comparison of ectopic pregnancy risk among transfers of embryos vitrified on day 3, day 5, and day 6. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 108–116.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norgard, B.M.; Catalini, L.; Jolving, L.R.; Larsen, M.D.; Friedman, S.; Fedder, J. The Efficacy of Assisted Reproduction in Women with a Wide Spectrum of Chronic Diseases—A Review. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 13, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, S.; Larsen, P.V.; Fedder, J.; Norgard, B.M. The reduced chance of a live birth in women with IBD receiving assisted reproduction is due to a failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy. Gut 2017, 66, 556–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messerlian, C.; Gaskins, A.J. Epidemiologic Approaches for Studying Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Design, Methods, Analysis and Interpretation. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2017, 4, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schober, P.; Vetter, T.R. Repeated Measures Designs and Analysis of Longitudinal Data: If at First You Do Not Succeed-Try, Try Again. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 127, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanderWeele, T.J. Principles of confounder selection. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundhedsministeriet. Lov om Ændring af lov om Assisteret Reproduktion i Forbindelse Med Behandling, Diagnostik og Forskning m.v. LOV nr 129 af 30/01/2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2021/129 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Sundhedsministeriet. Bekendtgørelse af lov om Assisteret Reproduktion i Forbindelse Med Behandling, Diagnostik og Forskning m.v. LBK nr 902 af 23/08/2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2019/902 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Chen, X.; Gissler, M.; Lavebratt, C. Birth outcomes in mothers with hypertensive disorders and polycystic ovary syndrome: A population-based cohort study. Hum. Reprod. Open 2023, 2023, hoad048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.Y.; Teng, B.; Fu, J.; Li, X.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, X.X. Obstetric and neonatal outcomes after transfer of vitrified early cleavage embryos. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 2093–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litzky, J.F.; Boulet, S.L.; Esfandiari, N.; Zhang, Y.; Kissin, D.M.; Theiler, R.N.; Marsit, C.J. Effect of frozen/thawed embryo transfer on birthweight, macrosomia, and low birthweight rates in US singleton infants. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 433.e1–433.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginstrom Ernstad, E.; Wennerholm, U.B.; Khatibi, A.; Petzold, M.; Bergh, C. Neonatal and maternal outcome after frozen embryo transfer: Increased risks in programmed cycles. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 126.e1–126.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Huang, J.; Liu, W.; Han, W.; Huang, G. Long-Term Storage Does Not Affect the Expression Profiles of mRNA and Long Non-Coding RNA in Vitrified-Warmed Human Embryos. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 751467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharasanit, T.; Colenbrander, B.; Stout, T.A. Effect of cryopreservation on the cellular integrity of equine embryos. Reproduction 2005, 129, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopeika, J.; Thornhill, A.; Khalaf, Y. The effect of cryopreservation on the genome of gametes and embryos: Principles of cryobiology and critical appraisal of the evidence. Hum. Reprod. Update 2015, 21, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Blastocyst Storage Time | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤3 Months | 4–6 Months | 7–12 Months | 13–24 Months | ≥25 Months | ||||||

| Embryo transfers (women) | 4430 | (3716) | 3820 | (3036) | 2205 | (1642) | 1047 | (793) | 1097 | (763) |

| Maternal age at oocyte retrieval, mean (SD) | 33.6 | (4.8) | 33.3 | (4.8) | 33.2 | (5.0) | 32.9 | (4.9) | 31.1 | (4.3) |

| ≤29 | 976 | (22.0%) | 898 | (23.5%) | 555 | (25.2%) | 270 | (25.8%) | 442 | (40.3%) |

| 30–34 | 1131 | (25.5%) | 1049 | (27.5%) | 534 | (24.2%) | 285 | (27.2%) | 318 | (29.0%) |

| 35–39 | 1199 | (27.1%) | 959 | (25.1%) | 541 | (24.5%) | 251 | (24.0%) | 227 | (20.7%) |

| ≥40 | 1124 | (25.4%) | 914 | (23.9%) | 575 | (26.1%) | 241 | (23.0%) | 110 | (10.0%) |

| Material age at embryo transfer | 33.8 | (4.9) | 33.6 | (4.9) | 33.9 | (5.0) | 34.3 | (4.9) | 34.4 | (4.4) |

| Paternal age, mean (SD) | 41.8 | (19.5) | 41.0 | (18.5) | 40.7 | (17.3) | 40.5 | (16.2) | 39.8 | (14.4) |

| Course of infertility, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Female factor | 533 | (12.0%) | 400 | (10.5%) | 203 | (9.2%) | 81 | (7.7%) | 71 | (6.5%) |

| Male factor | 1424 | (32.1%) | 1231 | (32.2%) | 676 | (30.7%) | 307 | (29.3%) | 405 | (36.9%) |

| Female/male and idiopathic | 2473 | (55.8%) | 2189 | (57.3%) | 1326 | (60.1%) | 659 | (62.9%) | 621 | (56.6%) |

| Fertilization method, n (%) | ||||||||||

| IVF | 2232 | (50.4%) | 1886 | (49.4%) | 1094 | (49.6%) | 464 | (44.3%) | 513 | (46.8%) |

| ICSI | 2060 | (46.5%) | 1788 | (46.8%) | 1040 | (47.2%) | 557 | (53.2%) | 560 | (51.0%) |

| IVF + ICSI | 20 | (0.5%) | 25 | (0.7%) | 15 | (0.7%) | <5 | (-) | 8 | (0.7%) |

| Testicular sperm aspiration | 118 | (2.7%) | 121 | (3.2%) | 56 | (2.5%) | 21 | (2.0%) | 16 | (1.5%) |

| Embryos transferred, n (%) | ||||||||||

| 1 | 3941 | (89.0%) | 3358 | (87.9%) | 1964 | (89.1%) | 917 | (87.6%) | 965 | (88.0%) |

| ≥2 | 489 | (11.0%) | 462 | (12.1%) | 241 | (10.9%) | 130 | (12.4%) | 132 | (12.0%) |

| Parity | ||||||||||

| 0 | 3005 | (67.8%) | 2778 | (72.7%) | 1694 | (76.8%) | 722 | (69.0%) | 218 | (19.9%) |

| 1 | 1227 | (27.7%) | 892 | (23.4%) | 421 | (19.1%) | 287 | (27.4%) | 755 | (68.8%) |

| >2 | 198 | (4.5%) | 150 | (3.9%) | 90 | (4.1%) | 38 | (3.6%) | 124 | (11.3%) |

| Previous embryos transferred, n (%) | ||||||||||

| 0 | 4191 | (94.6%) | 2479 | (64.9%) | 849 | (38.5%) | 403 | (38.5%) | 692 | (63.1%) |

| 1 | 239 | (5.4%) | 1312 | (34.3%) | 1194 | (54.1%) | 460 | (43.9%) | 329 | (30.0%) |

| ≥2 | 0 | (0.0%) | 29 | (0.8%) | 162 | (7.3%) | 184 | (17.6%) | 76 | (6.9%) |

| Hormone treatment | ||||||||||

| hCG Natural cycles | 954 | (21.5%) | 763 | (20.0%) | 364 | (16.5%) | 146 | (13.9%) | 123 | (11.2%) |

| Progesterone/estrogen Substituted cycles | 1348 | (30.4%) | 1138 | (29.8%) | 630 | (28.6%) | 318 | (30.4%) | 341 | (31.1%) |

| Other Stimulatated cycle | 2100 | (47.4%) | 1899 | (49.7%) | 1193 | (54.1%) | 567 | (54.2%) | 625 | (57.0%) |

| Missing | 28 | (0.6%) | 20 | (0.5%) | 18 | (0.8%) | 16 | (1.5%) | 8 | (0.7%) |

| BMI, N (%) | ||||||||||

| <18.5 (underweight) | 139 | (3.1%) | 136 | (3.6%) | 58 | (2.6%) | 24 | (2.3%) | 38 | (3.5%) |

| 18.5–25 (normal) | 2385 | (53.8%) | 2036 | (53.3%) | 1169 | (53.0%) | 513 | (49.0%) | 529 | (48.2%) |

| 25–30 (pre-obesity) | 903 | (20.4%) | 757 | (19.8%) | 432 | (19.6%) | 258 | (24.6%) | 216 | (19.7%) |

| 30–35 (obese I) | 280 | (6.3%) | 275 | (7.2%) | 151 | (6.8%) | 73 | (7.0%) | 89 | (8.1%) |

| ≥35 (obese II-III) | 51 | (1.2%) | 61 | (1.6%) | 25 | (1.1%) | 19 | (1.8%) | 18 | (1.6%) |

| BMI missing | 672 | (15.2%) | 555 | (14.5%) | 370 | (16.8%) | 160 | (15.3%) | 207 | (18.9%) |

| Smoking at the time of embryo transfer, N (%) | ||||||||||

| No | 3803 | (85.8%) | 3232 | (84.6%) | 1812 | (82.2%) | 854 | (81.6%) | 944 | (86.1%) |

| Yes | 258 | (5.8%) | 244 | (6.4%) | 141 | (6.4%) | 69 | (6.6%) | 68 | (6.2%) |

| Missing | 369 | (8.3%) | 344 | (9.0%) | 252 | (11.4%) | 124 | (11.8%) | 85 | (7.7%) |

| Alcohol at the time of embryo transfer, N (%) | ||||||||||

| No | 2002 | (45.2%) | 1735 | (45.4%) | 1002 | (45.4%) | 499 | (47.7%) | 494 | (45.0%) |

| Yes (1–2 units) | 991 | (22.4%) | 880 | (23.0%) | 480 | (21.8%) | 213 | (20.3%) | 246 | (22.4%) |

| Yes (>2 units) | 678 | (15.3%) | 570 | (14.9%) | 317 | (14.4%) | 154 | (14.7%) | 156 | (14.2%) |

| Missing | 759 | (17.1%) | 635 | (16.6%) | 406 | (18.4%) | 181 | (17.3%) | 201 | (18.3%) |

| Comorbidity | ||||||||||

| Polycystic ovary syndrome, PCOS | 116 | (2.6%) | 131 | (3.4%) | 96 | (4.4%) | 54 | (5.2%) | 73 | (6.7%) |

| Endometrioses | 274 | (6.2%) | 212 | (5.5%) | 149 | (6.8%) | 92 | (8.8%) | 78 | (7.1%) |

| The calendar year of infertility treatment, N (%) | ||||||||||

| 2012–2013 | 439 | (9.9%) | 307 | (8.0%) | 121 | (5.5%) | 67 | (6.4%) | 91 | (8.3%) |

| 2014–2015 | 1012 | (22.8%) | 851 | (22.3%) | 441 | (20.0%) | 162 | (15.5%) | 194 | (17.7%) |

| 2016–2017 | 1770 | (40.0%) | 1558 | (40.8%) | 906 | (41.1%) | 401 | (38.3%) | 404 | (36.8%) |

| 2018–2019 | 1209 | (27.3%) | 1104 | (28.9%) | 737 | (33.4%) | 417 | (39.8%) | 408 | (37.2%) |

| Blastocyst Storage Time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤3 Months | 4–6 Months | 7–12 Months | 13–24 Months | ≥25 Months | |

| Biochemical pregnancy (hCG) | 2.007 (45.3%) | 1.701 (44.5%) | 939 (42.4%) | 444 (42.4%) | 502 (45.8%) |

| OR | Ref. | 1.00 (0.91–1.09) | 0.93 (0.83–1.03) | 0.91 (0.78–1.05) | 1.02 (0.88–1.18) |

| aOR a | Ref. | 1.01 (0.90–1.09) | 0.95 (0.84–1.08) | 0.94 (0.80–1.11) | 0.96 (0.82–1.12) |

| Clinical Pregnancy (ultrasound) | 1.583 (35.7%) | 1302 (34.1%) | 667 (30.2%) | 350 (33.4%) | 397 (36.2%) |

| OR | Ref. | 0.96 (0.87–1.05) | 0.81 (0.72–0.91) | 0.95 (0.82–1.11) | 1.03 (0.89–1.20) |

| aOR a | Ref. | 0.99 (0.89–1.09) | 0.86 (0.76–0.98) | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) | 0.96 (0.82–1.13) |

| Live birth | 1.267 (28.6%) | 1.022 (26.8%) | 524 (23.8%) | 276 (26.4%) | 312 (28.3%) |

| OR | Ref. | 0.94 (0.85–1.05) | 0.84 (0.74–0.96) | 1.00 (0.84–1.19) | 1.02 (0.87–1.20) |

| aOR a | Ref. | 0.97 (0.87–1.08) | 0.88 (0.76–1.01) | 1.03 (0.86–1.23) | 0.89 (0.75–1.06) |

| Blastocyst Storage Time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤3 Months | 4–6 Months | 7–12 Months | 13–24 Months | ≥25 Months | |

| Preterm birth | 78 (8.0%) | 66 (8.4%) | 32 (8.3%) | 11 (6.0%) | 10 (4.5%) |

| OR | Ref. | 1.06 (0.76–1.50) | 1.01 (0.71–1.68) | 0.74 (0.39–1.43) | 0.55 (0.27–1.06) |

| aOR a | Ref. | 0.98 (0.69–1.40) | 1.07 (0.69–1.64) | 0.75 (0.39–1.46) | 0.56 (0.28–1.15) |

| Small for gestational age b | 149 (15.2%) | 113 (14.4%) | 53 (14.3) | 25 (13.7%) | 23 (10.4%) |

| OR | Ref. | 0.94 (0.72–1.22) | 0.94 (0.67–1.32) | 0.89 (0.56–1.40) | 0.65 (0.41–1.06) |

| aOR a | Ref. | 0.92 (0.71–1.21) | 0.92 (0.65–1.30) | 0.93 (0.58–1.49) | 1.02 (0.61–1.68) |

| Large for gestational age b | 59 (6.0%) | 59 (7.5%) | 21 (5.7%) | 18 (9.9%) | 26 (11.7%) |

| OR | Ref. | 1.27 (0.87–1.84) | 0.94 (0.57–1.58) | 1.71 (0.98–2.97) | 2.11 (1.29–3.42) |

| aOR a | Ref. | 1.24 (0.84–1.81) | 0.93 (0.55–1.57) | 1.54 (0.88–2.72) | 1.42 (0.84–2.42) |

| Congenital malformations | 98 (1.00%) | 75 (9.6%) | 35 (9.4%) | 20 (10.1%) | 18 (8.1%) |

| OR | Ref. | 0.95 (0.69–1.31) | 0.93 (0.63–1.41) | 1.11 (0.67–1.85) | 0.80 (0.47–1.34) |

| aOR a | Ref. | 0.95 (0.69–1.30) | 0.88 (0.58–1.33) | 1.15 (0.68–1.92) | 1.00 (0.57–1.75) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Eskildsen, T.V.; Larsen, M.D.; Fedder, J.; Jølving, L.R. Does Prolonged Preservation of Blastocysts Affect the Implantation and Live Birth Rate? A Danish Nationwide Register-Based Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031072

Eskildsen TV, Larsen MD, Fedder J, Jølving LR. Does Prolonged Preservation of Blastocysts Affect the Implantation and Live Birth Rate? A Danish Nationwide Register-Based Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031072

Chicago/Turabian StyleEskildsen, Tilde Veng, Michael Due Larsen, Jens Fedder, and Line Riis Jølving. 2026. "Does Prolonged Preservation of Blastocysts Affect the Implantation and Live Birth Rate? A Danish Nationwide Register-Based Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031072

APA StyleEskildsen, T. V., Larsen, M. D., Fedder, J., & Jølving, L. R. (2026). Does Prolonged Preservation of Blastocysts Affect the Implantation and Live Birth Rate? A Danish Nationwide Register-Based Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031072