Efficacy and Safety of Radiotherapy in Head and Neck Paragangliomas: A Retrospective 23-Year Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HNPGs | Head and neck paragangliomas |

| RT | radiotherapy |

| IMRT | intensity-modulated radiotherapy |

| LC | Local control |

| PGs | paragangliomas |

| CBT | carotid body neoplasms |

| SDH | succinate dehydrogenase |

| CT | computed tomography |

| DSA | Digital subtraction angiography |

| TORS | transoral robotic surgery |

| SBRT | Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy |

| SRS | Stereotactic radiosurgery |

| EBRT | external beam radiotherapy |

| GTV | Gross tumor volume |

| IGRT | image-guided radiotherapy |

| PTV | planning target volume |

| CTCAE | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

References

- Wasserman, P.G.; Savargaonkar, P. Paragangliomas: Classification, pathology, and differential diagnosis. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 34, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, J.M.; Ossoff, R.H. Paragangliomas of the head and neck. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 1986, 19, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, M. The Role of Radiotherapy in the Management of Paraganglioma. Otorhinolaryngol. Clin. Int. J. 2011, 3, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, I.; Aarabi Moghaddam, F.; Zamani, M.M.; Salimi, J. Clinical characteristics and remedies in 45 Iranians with carotid body tumors. Acta Med. Iran. 2012, 50, 339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Offergeld, C.; Brase, C.; Yaremchuk, S.; Mader, I.; Rischke, H.C.; Gläsker, S.; Schmid, K.W.; Wiech, T.; Preuss, S.F.; Suárez, C.; et al. Head and neck paragangliomas: Clinical and molecular genetic classification. Clinics 2012, 67, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieneke, J.A.; Smith, A. Paraganglioma: Carotid body tumor. Head Neck Pathol. 2009, 3, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafri, M.; Whitworth, J.; Rattenberry, E.; Vialard, L.; Kilby, G.; Kumar, A.V.; Izatt, L.; Lalloo, F.; Brennan, P.; Cook, J.; et al. Evaluation of SDHB, SDHD and VHL gene susceptibility testing in the assessment of individuals with non-syndromic phaeochromocytoma, paraganglioma and head and neck paraganglioma. Clin. Endocrinol. 2013, 78, 898–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werter, I.M.; Rustemeijer, C. Head and neck paragangliomas. Neth. J. Med. 2013, 71, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lassen-Ramshad, Y.; Ozyar, E.; Alanyali, S.; Poortmans, P.; van Houtte, P.; Sohawon, S.; Esassolak, M.; Krengli, M.; Villa, S.; Miller, R.; et al. Paraganglioma of the head and neck region, treated with radiation therapy, a Rare Cancer Network study. Head Neck 2019, 41, 1770–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boedeker, C.C.; Ridder, G.J.; Schipper, J. Paragangliomas of the head and neck: Diagnosis and treatment. Fam. Cancer 2005, 4, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, F.; Huwart, L.; Jourdan, G.; Reizine, D.; Herman, P.; Vicaut, E.; Guichard, J.P. Head and Neck Paragangliomas: Value of Contrast-Enhanced 3D MR Angiography. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2008, 29, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, R.; Schepers, A.; de Bruïne, F.T.; Liauw, L.; Mertens, B.J.; van der Mey, A.G.; van Buchem, M.A. The value of MR angiography techniques in the detection of head and neck paragangliomas. Eur. J. Radiol. 2004, 52, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.A.; Pattison, D.A.; Tothill, R.W.; Kong, G.; Akhurst, T.J.; Hicks, R.J.; Hofman, M.S. (68)Ga-DOTATATE and (18)F-FDG PET/CT in Paraganglioma and Pheochromocytoma: Utility, patterns and heterogeneity. Cancer Imaging 2016, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, T.T.G.; Timmers, H.; Marres, H.A.M.; Kunst, H.P.M. Feasibility of a wait-and-scan period as initial management strategy for head and neck paraganglioma. Head Neck 2017, 39, 2088–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, W.C.; Grignon, D.J.; Romano, W. Malignant paraganglioma with skeletal metastases and spinal cord compression: Response and palliation with chemotherapy. Clin. Oncol. (R. Coll. Radiol.) 1993, 5, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heesters, A.F.; Tops, C.; Potjer, T.; Corssmit, E.P.M.; Bayley, J.P.; Hensen, E.; Jansen, J. Optimal Screening for Hereditary Head and Neck Paraganglioma in Asymptomatic SDHx Variant Carriers in the Netherlands. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base 2025, 86, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, L.; Pacak, K.; Steichen, O.; Akker, S.A.; Aylwin, S.J.B.; Baudin, E.; Buffet, A.; Burnichon, N.; Clifton-Bligh, R.J.; Dahia, P.L.M.; et al. International consensus on initial screening and follow-up of asymptomatic SDHx mutation carriers. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz Gaviria, A.M.; Nuñez Ovaez, E.E.; Saldivar Rodea, C.A.; Sanchez, A.F.S. Carotid paragangliomas. Alternatives for presurgical endovascular management. Radiol. Case Rep. 2022, 17, 3785–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, A.H.; Bower, T.C.; Kasperbauer, J.; Link, M.J.; Oderich, G.; Cloft, H.; Young, W.F., Jr.; Gloviczki, P. Impact of preoperative embolization on outcomes of carotid body tumor resections. J. Vasc. Surg. 2012, 56, 979–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaspyrou, K.; Mewes, T.; Rossmann, H.; Fottner, C.; Schneider-Raetzke, B.; Bartsch, O.; Schreckenberger, M.; Lackner, K.J.; Amedee, R.G.; Mann, W.J. Head and neck paragangliomas: Report of 175 patients (1989–2010). Head Neck 2012, 34, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, U. Infratemporal fossa approach for glomus tumors of the temporal bone. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1982, 91, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, C.; Ganly, I.; Shah, J.P. Head and neck paragangliomas: 30-year experience. Head Neck 2020, 42, 2486–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.G.; Netterville, J.L.; Mendenhall, W.M.; Isaacson, B.; Nussenbaum, B. Head and Neck Paragangliomas: An Update on Evaluation and Management. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 154, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnny, C.; Huang, S.H.; Waldron, J.; O’Sullivan, B.; Su, J.; Bayley, A.; Goldstein, D.; Gullane, P.; Ringash, J.G.; Kim, J.; et al. Definitive Radiotherapy for Head and Neck Paragangliomas—A Single-Institution 30-Year Experience. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2022, 114, e292–e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.C.; Lee, J.W.; Ledbetter, L.; Wick, C.C.; Riska, K.M.; Cunningham, C.D.; Russomando, A.C.; Truong, T.; Hong, H.; Kuchibhatla, M.; et al. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis for Surgery Versus Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Jugular Paragangliomas. Otol. Neurotol. 2023, 44, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chino, J.P.; Sampson, J.H.; Tucci, D.L.; Brizel, D.M.; Kirkpatrick, J.P. Paraganglioma of the head and neck: Long-term local control with radiotherapy. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 32, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, G.P.; Da Roz, L.M.; de Carvalho Gico, V.; Weltman, E.; De Souza, E.C.; Baraldi, H.E.; Figueiredo, E.G.; Carlotti, C.G. Debulking surgery prior to stereotactic radiotherapy for head and neck paragangliomas. Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2024, 29, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, T.T.G.; Timmers, H.; Marres, H.A.M.; Kaanders, J.; Kunst, H.P.M. Results of a systematic literature review of treatment modalities for jugulotympanic paraganglioma, stratified per Fisch class. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2018, 43, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.L.; Khattab, M.H.; Anderson, C.; Sherry, A.D.; Luo, G.; Manzoor, N.; Attia, A.; Netterville, J.; Cmelak, A.J. Long-term Outcomes for the Treatment of Paragangliomas in the Upfront, Adjuvant, and Salvage Settings With Stereotactic Radiosurgery and Intensity-modulated Radiotherapy. Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 41, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.K.; Rodríguez-López, J.L.; Hirsch, B.E.; Burton, S.A.; Flickinger, J.C.; Clump, D.A. Long term outcomes with linear accelerator stereotactic radiosurgery for treatment of jugulotympanic paragangliomas. Head Neck 2021, 43, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougier, G.; Rochand, A.; Bourdais, R.; Meillan, N.; Tankere, F.; Herman, P.; Riet, F.; Mazeron, J.-J.; Burnichon, N.; Lussey-Lepoutre, C.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes in Head and Neck Paragangliomas Managed with Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy. Laryngoscope 2023, 133, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbo, P.; Morris, C.G.; Amdur, R.J.; Werning, J.W.; Dziegielewski, P.T.; Kirwan, J.; Mendenhall, W.M. Radiotherapy for benign head and neck paragangliomas: A 45-year experience. Cancer 2014, 120, 3738–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, W.M.; Hinerman, R.W.; Amdur, R.J.; Stringer, S.P.; Antonelli, P.J.; Singleton, G.T.; Cassisi, N.J. Treatment of paragangliomas with radiation therapy. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 34, 1007–1020, vii–viii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.A.; Elkon, D.; Lim, M.L.; Constable, W.C. Optimum dose of radiotherapy for chemodectomas of the middle ear. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1980, 6, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.G.; Nedzi, L.A.; Choe, K.S.; Abdulrahman, R.E.; Chen, S.A.; Yordy, J.S.; Timmerman, R.D.; Kutz, J.W.; Isaacson, B. A retrospective analysis of tumor volumetric responses to five-fraction stereotactic radiotherapy for paragangliomas of the head and neck (glomus tumors). Stereotact. Funct. Neurosurg. 2014, 92, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krych, A.J.; Foote, R.L.; Brown, P.D.; Garces, Y.I.; Link, M.J. Long-term results of irradiation for paraganglioma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2006, 65, 1063–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberson, R.E.; Adler, J.R.; Soltys, S.G.; Choi, C.; Gibbs, I.C.; Chang, S.D. Stereotactic radiosurgery as the primary treatment for new and recurrent paragangliomas: Is open surgical resection still the treatment of choice? World Neurosurg. 2012, 77, 745–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, G.J.; Maisel, R.H.; Ogura, J.H. Glomus jugulare tumors. II. A clinicopathologic analysis of the effects of radiotherapy. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1974, 83, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 53.0 (37–72) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 12 (85.7) |

| Male | 2 (14.3) |

| Tumor location, n (%) | |

| Right Jugular | 5 (33.3) |

| Left Jugular | 6 (40) |

| Jugular-CPA/CPA | 2 (1.3) |

| Right Jugulotympanic | 1 (0.6) |

| Bilateral Carotid | 1 (0.6) |

| Presenting symptoms, n (%) | |

| Tinnitus/Bu ing | 8 (53.3) |

| Hearing impairment/Loss | 6 (40) |

| Di iness | 3 (0.2) |

| Facial paralysis | 1 (0.6) |

| Headache | 1 (0.6) |

| Other | 4 (26.6) |

| Patient Number | RT Technique | Dose cGy | Fraction Size | PTV, cm3 | Clinical Outcome | Presenting Symptomes | RT Response, 3 Month (%) | RT Response, >24 Month (%) | LC * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3D-CRT | 5040 | 28 | 50 | Stable | Tinnitus | 20 | 70 | 100 |

| 2 | 3D-CRT | 5040 | 28 | 30 | Stable | Tinnitus | 30 | 80 | 100 |

| 3 | 3D-CRT | 5040 | 28 | 95 | Stable | Tinnitus | 10 | 70 | 100 |

| 4 | IMRT | 5040 | 28 | 60 | Improved | Tinnitus | 20 | 50 | 100 |

| 5 | 3D-CRT | 4500 | 25 | 20 | Resolved | - | 20 | 80 | 100 |

| 6 | IMRT | 4500 | 25 | 85 | Improved | Facial paralysis | 10 | 50 | 100 |

| 7 | IMRT | 4500 | 25 | 170 | Resolved | - | 20 | 60 | 100 |

| 8 | 3D-CRT | 4500 | 25 | 80 | Stable | Throat and ear pain | 10 | 50 | 100 |

| 9 | IMRT | 4500 | 25 | 25 | Improved | Hearing loss | 20 | 60 | 100 |

| 10 | IMRT | 4500 | 25 | 75 | Improved | Tinnitus | 20 | 70 | 100 |

| 11 | IMRT | 2500 | 5 | 25 | Stable | Hearing loss, hoarseness | 30 | 60 | 100 |

| 12 | IMRT | 5400 | 25 | 45 | Resolved | - | 30 | 100 | 100 |

| 13 | IMRT | 4500 | 25 | 50 | Improved | Tinnitus | 10 | 60 | 100 |

| 14 | IMRT | 5400 | 27 | 55 | Resolved | - | 20 | 80 | 100 |

| 15 | IMRT | 5000 | 25 | 65 | Resolved | - | 20 | 70 | 100 |

| Variable | Median/n (%) |

|---|---|

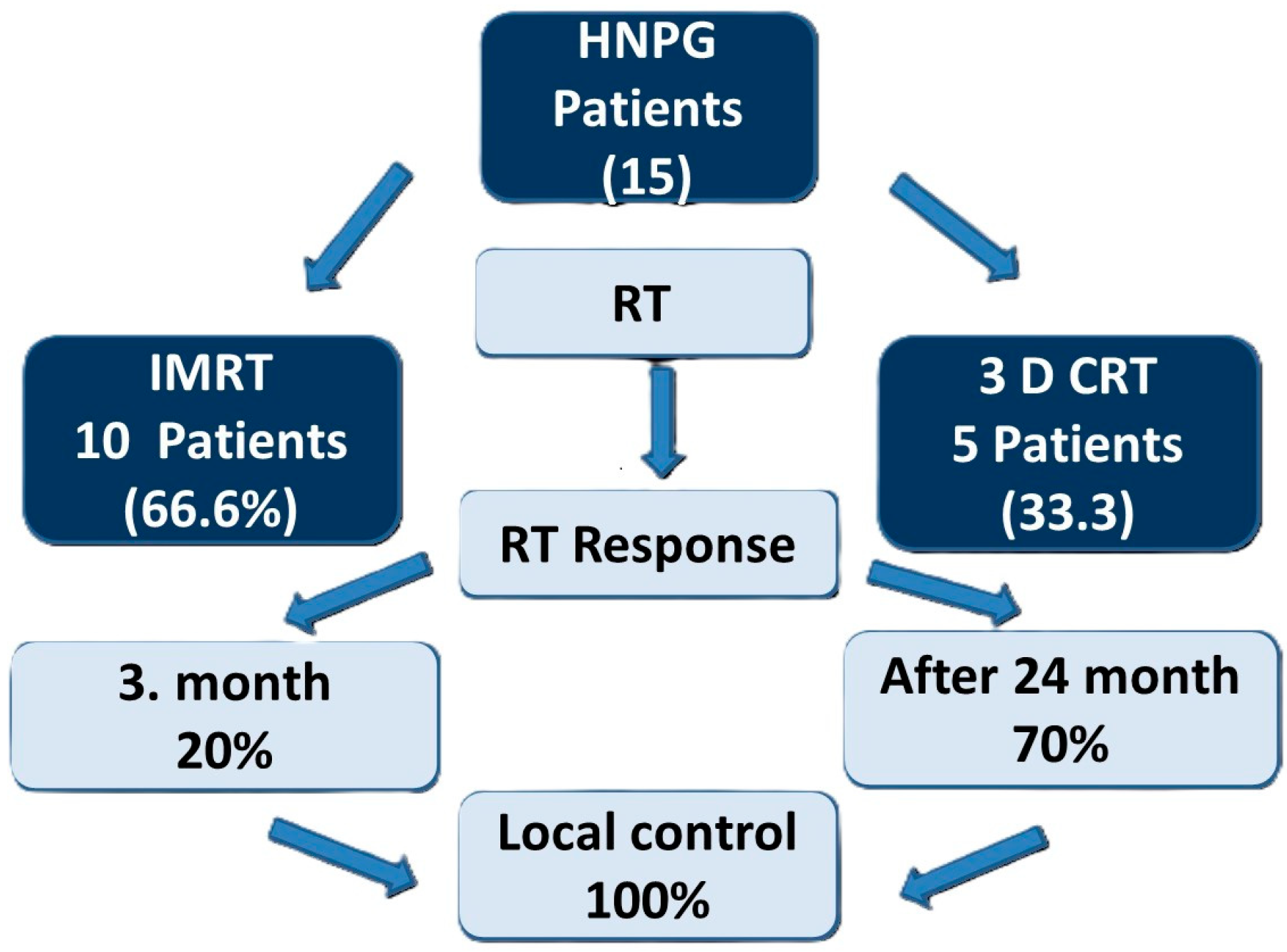

| RT technique | IMRT: 10 (66.6%) |

| 3D-CRT: 5 (33.3%) | |

| Dose, cGy | 4500 (2500–5400) |

| Fractions | 25 (5–28) |

| PTV, cm3 | 55 (20–172) |

| GTV, cm3 | 51 (14–163) |

| Variables | Values n (%) |

|---|---|

| Local control | 15 (%100) |

| RT response, 3 Month (%) | 20 (0–50) |

| RT response, >24 Month (%) | 70 (50–100) |

| Clinical Outcome (Symptoms) | Stable *: 5 (33.3%) |

| Improved: 5 (33.3%) | |

| Resolved: 5 (33.3%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cepni, K.; Dagdelen, M.; Oner, H.; Cepni, B.; Kiziltan, H.S.; Uzel, O.E. Efficacy and Safety of Radiotherapy in Head and Neck Paragangliomas: A Retrospective 23-Year Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031062

Cepni K, Dagdelen M, Oner H, Cepni B, Kiziltan HS, Uzel OE. Efficacy and Safety of Radiotherapy in Head and Neck Paragangliomas: A Retrospective 23-Year Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031062

Chicago/Turabian StyleCepni, Kimia, Meltem Dagdelen, Huseyin Oner, Bahar Cepni, Huriye Senay Kiziltan, and Omer Erol Uzel. 2026. "Efficacy and Safety of Radiotherapy in Head and Neck Paragangliomas: A Retrospective 23-Year Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031062

APA StyleCepni, K., Dagdelen, M., Oner, H., Cepni, B., Kiziltan, H. S., & Uzel, O. E. (2026). Efficacy and Safety of Radiotherapy in Head and Neck Paragangliomas: A Retrospective 23-Year Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031062