Complications of Free Flap Reconstruction in Maxillary and Mandibular Defects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

2.2. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Collection Process

2.4. Outcomes and Definitions

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Reconstruction Site Complications

3.3.1. Fibular Free Flap

3.3.2. Scapular Free Flap

3.3.3. Deep Circumflex Iliac Artery (DCIA) Free Flaps

3.4. Risk of Bias Within Studies

3.5. Quantitative Meta-Analysis: Overall Complications

3.5.1. Overall Flap Loss

3.5.2. Overall Partial Flap Loss

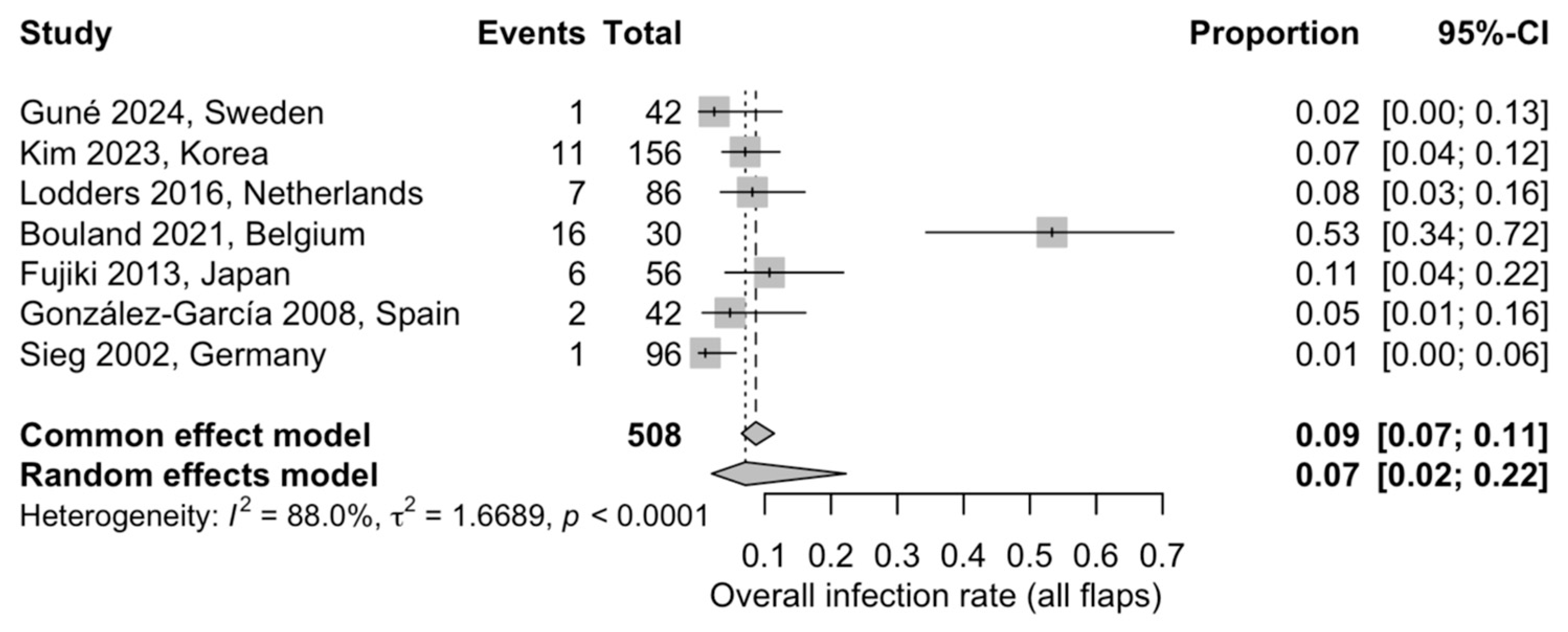

3.5.3. Overall Postoperative Infection

3.5.4. Overall Fistula Formation

3.5.5. Overall Wound Dehiscence

3.6. Quantitative Meta-Analysis—Flap-Related Complications

3.6.1. Fibular Free Flap

3.6.2. Scapular Free Flap

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Bianchi, B.; Ferri, A.; Ferrari, S.; Copelli, C.; Perlangeli, G.; Leporati, M.; Ferri, T.; Sesenna, E. Reconstruction of Mandibular Defects Using the Scapular Tip Free Flap. Microsurgery 2015, 35, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, L.Q.M. Head and Neck Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troise, S.; De Fazio, G.R.; Committeri, U.; Spinelli, R.; Nocera, M.; Carraturo, E.; Salzano, G.; Arena, A.; Abbate, V.; Bonavolontà, P.; et al. Mandibular Reconstruction after Post-Traumatic Complex Fracture: Comparison Analysis between Traditional and Virtually Planned Surgery. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 126, 102029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Baar, G.J.C.; Lodders, J.N.; Chhangur, C.; Leeuwrik, L.; Forouzanfar, T.; Liberton, N.P.T.J.; Berkhout, W.E.R.; Winters, H.A.H.; Leusink, F.K.J. The Amsterdam UMC Protocol for Computer-Assisted Mandibular and Maxillary Reconstruction; A Cadaveric Study. Oral Oncol. 2022, 133, 106050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prucher, G.M.; Gaggio, L.; Neri, F.; Astarita, F.; Sani, L.; Desiderio, C.; Allegri, D.; Pauro, N.; Sandi, A.; Baietti, A.M. Conformational Reconstruction in Head and Neck Bone Cancer: Could Fibula Free Flap Become the Gold Standard Flap? J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- akushima, A.; Harii, K.; Asato, H.; Nakatsuka, T.; Kimata, Y. Mandibular reconstruction using microvascular free flaps: A statistical analysis of 178 cases. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2001, 108, 1555–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.J.; Zhang, K.K.; Cohen, Z.; Shahzad, F.; Nelson, J.A.; McCarthy, C.M.; Patel, S.G.; Boyle, J.O.; Shah, J.P.; Disa, J.J.; et al. Reconstructing Segmental Mandibular Defects: A Single-Center, 21-Year Experience with 413 Fibula Free Flaps. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, V.; Gennaro, P.; Torroni, A.; Longo, G.; Aboh, I.V.; Cassoni, A.; Battisti, A.; Anelli, A. Scapula Free Flap for Complex Maxillofacial Reconstruction. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2009, 20, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimovska, E.O.F.; Aazar, M.; Bengtsson, M.; Thor, A.; Klasson, S.; Rodriguez-Lorenzo, N. Clinical Outcomes of Scapular versus Fibular Free Flaps in Head and Neck Reconstructions: A Retrospective Study of 120 Patients. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2025, 155, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Ferri, A.; Bianchi, B. Scapular Tip Free Flap in Head and Neck Reconstruction. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 23, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferri, A.; Perlangeli, G.; Zito, F.; Ferrari, S.; Bianchi, B.; Arcuri, F.; Poli, T. Technical Refinements of the Scapular Tip-Free Flap for Mandibular Reconstruction. Microsurgery 2024, 44, e31176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelo, E.; Richter, J.E.; Arias-Valderrama, O.; Pirgousis, P.; Patel, S. A Systematic Review of Functional Donor-Site Morbidity in Scapular Bone Transfer. Microsurgery 2025, 45, e70044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, P.-J.; Dons, F.; Van Bever, P.-J.; Schoenaers, J.; Nanhekhan, L.; Politis, C. Fibula Free Flap in Head and Neck Reconstruction: Identifying Risk Factors for Flap Failure and Analysis of Postoperative Complications in a Low Volume Setting. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstr. 2019, 12, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi Manfroni, A.; Sako, M.; Mataj, N.; Zhupa, D.; Laganà, F. Case Report: Free Fibula Flap for Post-Oncologic Mandibular Reconstruction, First Experience in Tirana. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1678310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonie, S.; Herle, P.; Paddle, A.; Pradhan, N.; Birch, T.; Shayan, R. Mandibular Reconstruction: Meta-Analysis of Iliac- versus Fibula-Free Flaps. ANZ J. Surg. 2016, 86, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, A.; Hyler, J.; Alamoudi, U.; Makki, F.; Domack, A.; Neel, G.; Biskup, M.; Haughey, B.H.; Magnuson, J.S. Outcomes of Free Flap Bony Reconstruction for Maxillary Defects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Laryngoscope 2025, 136, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaine, A.; Pitak-Arnnop, P.; Hivelin, M.; Dhanuthai, K.; Bertrand, J.C.; Bertolus, C. Postoperative Complications of Fibular Free Flaps in Mandibular Reconstruction: An Analysis of 25 Consecutive Cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2009, 108, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guné, H.; Sjövall, J.; Becker, M.; Elebro, K.; Hafström, A.; Tallroth, L.; Klasson, S. Evaluating the Efficacy and Complications of the Scapular Osseous Free Flap for Head and Neck Reconstruction: Results from a Population-Based Cohort. JPRAS Open 2024, 42, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Choi, N.; Kim, D.; Jeong, H.S.; Son, Y.I.; Chung, M.K.; Baek, C.H. Vascularized Osseous Flaps for Head and Neck Reconstruction: Comparative Analysis Focused on Complications and Salvage Options. Auris Nasus Larynx 2023, 50, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodders, J.N.; Schulten, E.A.J.M.; De Visscher, J.G.A.M.; Forouzanfar, T.; Karagozoglu, K.H. Complications and Risk after Mandibular Reconstruction with Fibular Free Flaps in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2016, 32, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, S.; Bera, R.N.; Tiwari, P. Outcome of Mandibular Reconstruction with Fibula Free Flaps: Retrospective Analysis of Complications. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 75, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parise, G.K.; Guebur, M.I.; Ramos, G.H.A.; Groth, A.K.; da Silva, A.B.D.; Sassi, L.M. Evaluation of Complications and Flap Losses in Mandibular Reconstruction with Microvascularized Fibula Flap. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 22, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendenbach, C.; Steffen, C.; Hanken, H.; Schluermann, K.; Henningsen, A.; Beck-Broichsitter, B.; Kreutzer, K.; Heiland, M.; Precht, C. Complication Rates and Clinical Outcomes of Osseous Free Flaps: A Retrospective Comparison of CAD/CAM versus Conventional Fixation in 128 Patients. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 48, 1156–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritschl, L.M.; Mücke, T.; Hart, D.; Unterhuber, T.; Kehl, V.; Wolff, K.D.; Fichter, A.M. Retrospective Analysis of Complications in 190 Mandibular Resections and Simultaneous Reconstructions with Free Fibula Flap, Iliac Crest Flap or Reconstruction Plate: A Comparative Single Centre Study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 2905–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouland, C.; Albert, N.; Boutremans, E.; Rodriguez, A.; Loeb, I.; Dequanter, D.; Javadian, R. Risk Factors Assessment in Fibular Free Flap Mandibular Reconstruction. Ann. De Chir. Plast. Esthet. 2021, 66, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowthwaite, S.A.; Theurer, J.; Belzile, M.; Fung, K.; Franklin, J.; Nichols, A.; Yoo, J. Comparison of Fibular and Scapular Osseous Free Flaps for Oromandibular Reconstruction: A Patient-Centered Approach to Flap Selection; American Medical Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013; Volume 139. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki, M.; Miyamoto, S.; Sakuraba, M.; Nagamatsu, S.; Hayashi, R. A Comparison of Perioperative Complications Following Transfer of Fibular and Scapular Flaps for Immediate Mandibular Reconstruction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2013, 66, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-García, R.; Naval-Gías, L.; Rodríguez-Campo, F.J.; Muñoz-Guerra, M.F.; Sastre-Pérez, J. Vascularized Free Fibular Flap for the Reconstruction of Mandibular Defects: Clinical Experience in 42 Cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2008, 106, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Guerra, M.F.; Naval Gías, L.; Rodríguez Campo, F.J.; Díaz González, F.J. Vascularized Free Fibular Flap for Mandibular Reconstruction: A Report of 26 Cases. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2001, 59, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieg, P.; Zieron, J.O.; Bierwolf, S.; Hakim, S.G. Defect-Related Variations in Mandibular Reconstruction Using Fibula Grafts. A Review of 96 Cases. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2002, 40, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Goel, M.; Gaikwad, P.; Mehendale, R.; Tiwari, S. Rehabilitation Outcome of Implants Placed in Free Fibula Flap Versus Iliac Crest Free Flap? A Systematic Review. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2025, 24, 1538–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copelli, C.; Cacciatore, F.; Cocis, S.; Maglitto, F.; Barbara, F.; Iocca, O.; Manfuso, A. Bone Reconstruction Using CAD/CAM Technology in Head and Neck Surgical Oncology. A Narrative Review of State of the Art and Aesthetic-Functional Outcomes. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2024, 44, S58–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.A.; Pusic, A.L. Free-Flap Mandibular Reconstruction: A 10-Year Follow-Up Study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2002, 110, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zeng, B.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, X.; Shao, Z.; Bu, L.; Sun, Y.; Ma, S.; Ma, C.; Shang, Z.; et al. Vascularized Iliac Crest Free Flap in Maxillofacial Reconstruction: Pearls and Pitfalls from 437 Clinical Application. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 126, 102318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhoot, A.; Mackenzie, A.; Rehman, U.; Adebayo, O.; Neves, S.; Sohaib Sarwar, M.; Brennan, P.A. Use of Scapular Tip Flaps in the Reconstruction of Head and Neck Defects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 62, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar-Domingo, M.J.; Bustos, V.P.; Akintayo, R.; Mahmoud, A.A.; Fanning, J.E.; Foppiani, J.A.; Miller, A.S.; Cauley, R.P.; Lin, S.J.; Lee, B.T. The Versatility of the Scapular Free Flap: A Workhorse Flap? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Microsurgery 2024, 44, e31203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author/Year/ | Country | Study Design | N Cases (Sex/Age) | Flap Type | Donor Site Complications | Reconstruction Site Complications | Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chaine 2009 [20] | France | Retrospective observational | 25 (80% M; mean 43 y) | 25 FFF | FFF:

| FFF:

| Mean 47 m |

| Guné 2024 [21] | Sweden | Retrospective observational | 42 (60% M; median 63 y) | 42 SFF | SFF:

| SFF:

| Mean 49 m |

| Kim 2023 [22] | Korea | Retrospective observational | 138 (68.1% M; mean 56 y) | 114 FFF; 42 SFF | FFF:

| FFF:

| Mean 44 m |

| Lodders 2016 [23] | Netherlands | Retrospective observational | 85 (45.9% M; mean 61.2 y) | 86 FFF | FFF:

| FFF:

| Mean 45 m |

| Murugan 2023 [24] | India | Retrospective observational | 242 (78.5% M; mean 44.3 y) | 242 FFF | FFF: not numerically quantified | FFF:

| Mean 20 m |

| Parise 2018 [25] | Brazil | Retrospective observational | 43 (51% M; mean 44 y) | 43 FFF | FFF: not reported | FFF:

| NR |

| Rendenbach 2019 [26] | Germany | Retrospective observational | 128 (64.1% M; mean 59.2 y) | 107 FFF; 8 SFF; 13 DCIA | FFF: not reported; SFF: not reported; DCIA: not reported | FFF:

| Mean 15.5 m |

| Ritschl 2021 [27] | Germany | Retrospective observational | 113 (63.7% M; mean 59 y) | 89 FFF; 24 DCIA | FFF: not reported; DCIA: not reported | FFF:

| Mean 61 m |

| Bouland 2021 [28] | Belgium | Retrospective observational | 30 (66.7% M; mean 52 y) | 30 FFF | FFF: not numerically quantified | FFF:

| NS |

| Dowthwaite 2013 [29] | Canada | Retrospective observational | 110 (61.8% M; mean 62 y) | 58 FFF; 55 SFF | FFF:

SFF:

| FFF:

| NR |

| Fujiki 2013 [30] | Japan | Retrospective observational | 56 (69.6% M; mean 63 y) | 38 FFF; 18 SFF | FFF:

| FFF:

| 1 m |

| González-García 2008 [31] | Spain | Retrospective observational | 42 (64.3% M; mean 52 y) | 42 FFF | FFF:

| FFF:

| Mean 20.5 m |

| Muñoz-Guerra 2001 [32] | Spain | Retrospective observational | 26 (80.8% M; mean 55.2 y) | 26 FFF | FFF:

| FFF:

| Mean 17 m |

| Sieg 2002 [33] | Germany | Retrospective observational | 93 (74.2% M; range 15–81 y) | 96 FFF | FFF: Not numerically quantified | FFF:

| NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Maglitto, F.; Troise, S.; Calabria, F.; Trotta, S.; Salzano, G.; Vaira, L.A.; Abbate, V.; Bonavolontà, P.; Dell’Aversana Orabona, G. Complications of Free Flap Reconstruction in Maxillary and Mandibular Defects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020797

Maglitto F, Troise S, Calabria F, Trotta S, Salzano G, Vaira LA, Abbate V, Bonavolontà P, Dell’Aversana Orabona G. Complications of Free Flap Reconstruction in Maxillary and Mandibular Defects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):797. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020797

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaglitto, Fabio, Stefania Troise, Federica Calabria, Serena Trotta, Giovanni Salzano, Luigi Angelo Vaira, Vincenzo Abbate, Paola Bonavolontà, and Giovanni Dell’Aversana Orabona. 2026. "Complications of Free Flap Reconstruction in Maxillary and Mandibular Defects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020797

APA StyleMaglitto, F., Troise, S., Calabria, F., Trotta, S., Salzano, G., Vaira, L. A., Abbate, V., Bonavolontà, P., & Dell’Aversana Orabona, G. (2026). Complications of Free Flap Reconstruction in Maxillary and Mandibular Defects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020797