Short- and Long-Term Responses to Pulmonary Rehabilitation in 922 Patients with COPD: A Real-World Database Study (2002–2019)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Pulmonary Rehabilitation Programme Description

2.4. Patient Selection

2.5. Assessments and Variables of Interest

2.6. Response Classification

2.7. Statistics

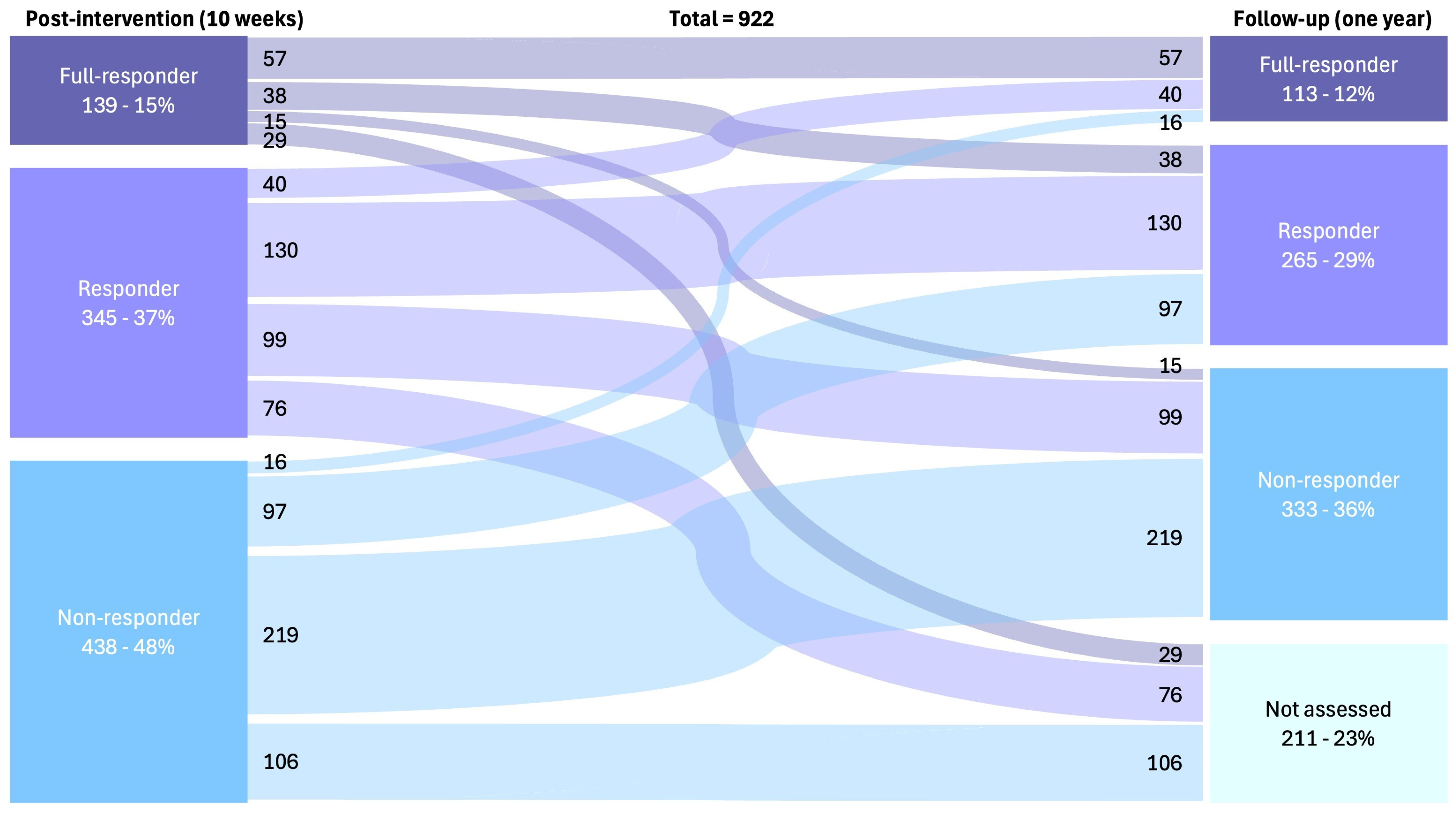

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 2025 GOLD Report—Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease—GOLD [Internet]. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease—GOLD. 2024. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/2025-gold-report/ (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Rochester, C.L.; Alison, J.A.; Carlin, B.; Jenkins, A.R.; Cox, N.S.; Bauldoff, G.; Bhatt, S.P.; Bourbeau, J.; Burtin, C.; Camp, P.G.; et al. Pulmonary Rehabilitation for Adults with Chronic Respiratory Disease: An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 208, e7–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Holland, A.E.; Cox, N.S.; Houchen-Wolloff, L.; Rochester, C.L.; Garvey, C.; ZuWallack, R.; Nici, L.; Limberg, T.; Lareau, S.C.; Yawn, B.P.; et al. An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, e12–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bondarenko, J.; Corso, S.D.; Dillon, M.P.; Singh, S.; Miller, B.R.; Kein, C.; Holland, A.E.; Jones, A.W. Clinically important changes and adverse events with centre-based or home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic respiratory disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chronic Respir. Dis. 2024, 21, 14799731241277808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaselvi, S.; Janmeja, A.K.; Aggarwal, D.; Sidana, A.; Sood, P. Predictors of response to pulmonary rehabilitation in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: A prospective cohort study. J. Postgrad. Med. 2019, 65, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitacca, M.; Malovini, A.; Paneroni, M.; Spanevello, A.; Ceriana, P.; Capelli, A.; Murgia, R.; Ambrosino, N. Predicting Response to In-Hospital Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Individuals Recovering From Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Arch. De Bronconeumol. 2024, 60, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenburg, W.A.; de Greef, M.H.; ten Hacken, N.H.; Wempe, J.B. A better response in exercise capacity after pulmonary rehabilitation in more severe COPD patients. Respir. Med. 2012, 106, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meo, F.; Pedone, C.; Lubich, S.; Pizzoli, C.; Traballesi, M.; Incalzi, R.A. Age does not hamper the response to pulmonary rehabilitation of COPD patients. Age Ageing 2008, 37, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestri, R.; Vitacca, M.; Paneroni, M.; Zampogna, E.; Ambrosino, N. Gender and Age as Determinants of Success of Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2023, 59, 174–177, (In English, Spanish). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielmanns, M.; Gloeckl, R.; Schmoor, C.; Windisch, W.; Storre, J.H.; Boensch, M.; Kenn, K. Effects on pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD or ILD: A retrospective analysis of clinical and functional predictors with particular emphasis on gender. Respir. Med. 2016, 113, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spruit, M.A.; Augustin, I.M.; Vanfleteren, L.E.; Janssen, D.J.; Gaffron, S.; Pennings, H.J.; Smeenk, F.; Pieters, W.; van den Bergh, J.J.; Michels, A.J.; et al. Differential response to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: Multidimensional profiling. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 46, 1625–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, N.J.; Evans, R.A.; Williams, J.E.; Green, R.H.; Singh, S.J.; Steiner, M.C. Does body mass index influence the outcomes of a Waking-based pulmonary rehabilitation programme in COPD? Chronic Respir. Dis. 2012, 9, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashmore, J.A.; Emery, C.F.; Hauck, E.R.; MacIntyre, N.R. Marital adjustment among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who are participating in pulmonary rehabilitation. Heart Lung 2005, 34, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafner, T.; Pirc Marolt, T.; Šelb, J.; Grošelj, A.; Kosten, T.; Simonič, A.; Košnik, M.; Korošec, P. Predictors of Success of Inpatient Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program in COPD Patients. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2023, 18, 2483–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackstock, F.C.; Webster, K.E.; McDonald, C.F.; Hill, C.J. Self-efficacy Predicts Success in an Exercise Training-Only Model of Pulmonary Rehabilitation for People with COPD. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2018, 38, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungerehabilitering—DLS|Dansk Lungemedicinsk Selskab. 3 March 2023. Available online: https://lungemedicin.dk/lungerehabilitering/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- NKR: Rehabilitering af Patienter Med KOL. 18 May 2018. Sundhedsstyrelsen. Available online: https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2018/NKR-Rehabilitering-af-patienter-med-KOL (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Holland, A.E.; Spruit, M.A.; Troosters, T.; Puhan, M.A.; Pepin, V.; Saey, D.; McCormack, M.C.; Carlin, B.W.; Sciurba, F.C.; Pitta, F.; et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: Field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 1428–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, S.; Diaz-Guzman, E.; Mannino, D.M. Influence of sex on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk and treatment outcomes. Int. J. COPD 2014, 9, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, B.R.; Cote, C.G. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altenburg, W.A.; Duiverman, M.L.; Ten Hacken, N.H.; Kerstjens, H.A.; de Greef, M.H.; Wijkstra, P.J.; Wempe, J.B. Changes in the endurance shuttle walk test in COPD patients with chronic respiratory failure after pulmonary rehabilitation: The minimal important difference obtained with anchor- and distribution-based method. Respir. Res. 2015, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.W. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2005, 2, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alma, H.; de Jong, C.; Jelusic, D.; Wittmann, M.; Schuler, M.; Flokstra-de Blok, B.; Kocks, J.; Schultz, K.; van der Molen, T. Health status instruments for patients with COPD in pulmonary rehabilitation: Defining a minimal clinically important difference. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2016, 26, 16041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kon, S.S.; Canavan, J.L.; Jones, S.E.; Nolan, C.M.; Clark, A.L.; Dickson, M.J.; Haselden, B.M.; Polkey, M.I.; Man, W.D. Minimum clinically important difference for the COPD Assessment Test: A prospective analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, V.A.; Masa, M.P.; Fernández, A.P.G.; Rodríguez, A.M.M.; Moreno, R.T.; Rubio, T.M. Patient Profile of Drop-Outs from a Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program. Arch. De Bronconeumol. 2017, 53, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoaas, H.; Morseth, B.; Holland, A.E.; Zanaboni, P. Are Physical activity and Benefits Maintained After Long-Term. Telerehabilitation in COPD? Int. J. Telerehabilit. 2016, 8, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariscal Aguilar, P.; Carpio Segura, C.; Tenes Mayen, A.; Zamarrón de Lucas, E.; Villamañán Bueno, E.; Marín Santos, M.; Álvarez-Sala Walther, R. Factors associated with poor long-term adherence after completing a pulmonary rehabilitation programme in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Work 2022, 73, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto-Miranda, S.; Mendes, M.A.; Cravo, J.; Andrade, L.; Spruit, M.A.; Marques, A. Functional Status Following Pulmonary Rehabilitation: Responders and Non-Responders. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitacca, M.; Paneroni, M.; Spanevello, A.; Ceriana, P.; Balbi, B.; Salvi, B.; Ambrosino, N. Effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation in individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease according to inhaled therapy: The Maugeri study. Respir. Med. 2022, 202, 106967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.; Torre, A.; Kallemose, T.; Ulrik, C.S.; Godtfredsen, N.S. Pulmonary telerehabilitation vs. conventional pulmonary rehabilitation—A secondary responder analysis. Thorax 2023, 78, 1039–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, N.S.; McDonald, C.; Burge, A.T.; Hill, C.J.; Bondarenko, J.; Holland, A.E. Comparison of Clinically Meaningful Improvements After Center-Based and Home-Based Telerehabilitation in People with COPD. Chest 2025, 167, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmari, A.D.; Kowlessar, B.S.; Patel, A.R.; Mackay, A.J.; Allinson, J.P.; Wedzicha, J.A.; Donaldson, G.C. Physical activity and exercise capacity in patients with moderate COPD exacerbations. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 48, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, C.L.; Vogiatzis, I.; Holland, A.E.; Lareau, S.C.; Marciniuk, D.D.; Puhan, M.A.; Spruit, M.A.; Masefield, S.; Casaburi, R.; Clini, E.M.; et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society policy statement: Enhancing implementation, use, and delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, J.R.; Morris, N.R.; McKeough, Z.J.; Yerkovich, S.T.; Paratz, J.D. A simple clinical measure of quadriceps muscle strength identifies responders to pulmonary rehabilitation. Pulm. Med. 2014, 2014, 782702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables (n) | Baseline Characteristics Total Population (n = 922) | Response After 10 Weeks | Response After One Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Response (n= 139) | Response (n = 345) | Non-Response (n = 438) | Full Response (n = 113) | Response (n = 265) | Non-Response (n = 333) | ||

| Age, yrs (920) | 69.2 ± 8.7 | 67.9 ± 8.9 ¶ | 68.8 ± 8.9 | 69.9 ± 8.4 * | 66.6 ± 9.3 ¶ | 68.6 ± 8.9 | 70.1 ± 8.0 * |

| Female sex, n (%) (922) | 577 (62.6) | 81 (58.3) | 226 (65.5) | 270 (61.6) | 70 (61.9) | 159 (60.0) | 214 (64.3) |

| FEV1, %pred (909) FEV1/FVC, % (885) | 35.5 ± 14.1 47.0 ± 13.9 | 33.9 ± 12.2 47.2 ± 13.0 | 36.2 ± 16.7 47.4 ± 14.7 | 35.5 ± 12.4 46.6 ± 13.5 | 35.4 ± 14.2 47.7 ± 13.4 | 35.9 ± 13.2 48.3 ± 13.7 ¶ | 34.3 ± 12.1 45.1 ± 14.3 # |

| GOLD I/II/III/IV, % (908) | 0.4/11.5/51.4/35.1 | 0/10.8/45.3/43.2 | 0.6/12.8/50.4/35.1 | 0.5/10.7/54.1/32.6 | 1.8/10.6/46.9/39.8 | 0.4/15.1/49.1/34.3 | 0.3/8.7/52.3/37.5 |

| Smoking status, % (912) Never/former/current Pack-year history, yrs (861) | 2.7/76.9/19.2 41.4 ± 25.3 | 3.6/69.8/24.5 40.9 ± 19.3 | 1.7/78.3/19.1 40.3 ± 18.9 | 3.2/78.1/17.6 42.3 ± 30.9 | 2.7/77.9/17.7 40.3 ± 21.0 | 1.1/79.2/18.5 41.0 ± 21.1 | 2.4/79.3/18.0 41.9 ± 30.5 |

| LTOT, n (%) (919) | 62 (6.7) | 12 (8.6) | 17 (4.9) | 33 (7.5) | 8 (7.1) | 16 (6.0) | 23 (6.9) |

| BMI, kg/m2 (915) | 25.6 ± 6.0 | 25.1 ± 5.9 | 25.6 ± 6.3 | 25.8 ± 5.8 | 25.4 ± 5.9 | 25.8 ± 6.0 | 25.4 ± 5.9 |

| Cardiac disease, n (%) (918) Musculoskeletal disease, n (%) (918) | 332 (36.0) 233 (25.3) | 51 (36.7) 44 (31.7) | 121 (35.1) 84 (24.3) | 160 (36.5) 105 (24.0) | 40 (35.4) 32 (28.3) | 99 (37.4) 62 (23.4) | 116 (34.8) 75 (22.5) |

| Number of hospital admissions within the last year, n (904) | 0.8 ± 1.5 | 1.0 ± 1.6 | 0.8 ± 1.5 | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 1.0 ± 1.5 | 0.7 ± 1.5 | 0.8 ± 1.4 |

| Number of hospital days within the last year, n (874) | 4.7 ± 10.0 | 5.3 ± 9.9 | 4.7 ± 10.6 | 4.6 ± 9.6 | 4.5 ± 8.1 | 4.4 ± 10.3 | 5.0 ± 10.7 |

| Current medication, n (%) SABA (913) LABA (914) LAMA (913) LABA + LAMA(922) LABA + ICS (922) LABA + LAMA + ICS (912) ICS (913) Oral steroids (913) | 774 (83.9) 438 (47.5) 705 (76.5) 339 (36.8) 366 (39.7) 296 (32.1) 752 (81.6) 61 (6.6) | 113 (81.3) 75 (54.0) 104 (74.8) 61 (43.9) 66 (47.5) 55 (39.6) 110 (79.1) 11 (7.9) | 291 (84.3) 162 (47.0) 258 (74.8) 117 (33.9) 139 (40.3) 106 (30.7) 289 (83.8) 22 (6.4) | 370 (84.5) 201 (45.9) 343 (78.3) 161 (36.8) 161 (36.8) 135 (30.8) 353 (80.6) 28 (6.4) | 92 (81.4) 53 (46.9) 88 (77.9) 43 (38.1) 48 (42.5) 39 (34.5) 97 (85.8) 10 (8.8) | 223 (84.2) 127 (47.9) 200 (75.5) 95 (35.8) 104 (39.2) 85 (32.1) 212 (80.0) 17 (6.4) | 287 (86.2) 154 (46.2) 263 (79.0) 120 (36.0) 133 (39.9) 105 (31.5) 281 (84.4) 24 (7.2) |

| Marital status, n (%) (917) Married/living with partner Living alone Nursing home | 440 (47.7) 476 (51.6) 1 (0.1) | 75 (54.0) 63 (45.3) 0 (0) | 154 (44.6) 190 (55.1) 1 (0.3) | 211 (48.2) 223 (50.9) 1 (0.1) | 58 (51.3) 55 (48.7) 0 (0.0) | 127 (47.9) 138 (52.1) 0 (0.0) | 153 (45.9) 177 (53.2) 1 (0.3) |

| Education years, n (898) | 9.0 ± 2.6 | 9.4 ± 2.6 | 8.9 ± 2.7 | 8.8 ± 2.3 | 9.5 ± 3.0 | 9.0 ± 2.4 | 8.7 ± 2.5 |

| Working status, n (%) (906) Working Retired Disability pension Vocational work placement | 30 (3.3) 288 (31.2) 305 (33.1) 283 (30.79) | 6 (4.3) 47 (33.8) 49 (35.3) 35 (25.2) | 11 (3.2) 112 (32.5) 118 (34.2) 101 (29.3) | 13 (3.0) 129 (29.5) 138 (31.5) 147 (33.6) | 6 (5.3) 33 (29.2) 39 (34.5) 33 (29.2) | 7 (2.6) 98 (37.0) 88 (33.2) 71 (26.8) | 11 (3.3) 106 (31.8) 105 (31.5) 105 (31.5) |

| Borg CR-10 score at rest (920) | 0.6 ± 1.0 | 0.7 ± 1.1 | 0.6 ± 1.1 | 0.6 ± 1.0 | 0.6 ± 1.0 | 0.6 ± 1.1 | 0.6 ± 1.1 |

| HR at rest (920) | 82.3 ± 14.0 | 82.9 ± 13.7 | 81.9 ± 15.0 | 82.3 ± 13.3 | 84.0 ± 15.9 | 83.0 ± 13.0 | 81.2 ± 14.3 |

| Saturation at rest (920) | 95.0 ± 26.5 | 93.9 ± 2.1 # ¶ | 94.3 ± 2.2 * ¶ | 95.9 ± 38.4 * # | 94.3 ± 2.1 | 97.2 ± 49.3 | 94.0 ± 2.1 |

| MRC score, median (IQR) (921) | 4.5 (1–5) | 3.5 (2–5) | 3.5 (1–5) | 4.5 (1–5) | 3.5 (2–5) | 3.5 (2–5) | 4.5 (2–5) |

| Endurance SWT Walking speed, km/h (910) Time, seconds (861) End HR (857) End saturation (%) (858) End Borg CR-10 score (860) | 3.3 ± 1.1 172.5 ± 93.4 107.7 ± 14.4 88.3 ± 5.5 4.8 ± 1.6 | 3.2 ± 0.9 180.7 ± 92.8 107.8 ± 12.6 88.3 ± 5.4 4.8 ± 1.5 | 3.3 ± 1.2 180.9 ± 100.8 ¶ 108.3 ± 15.3 88.6 ± 5.4 4.9 ± 1.6 | 3.3 ± 1.0 163.2 ± 86.5 # 107.3 ± 14.1 88.0 ± 5.6 4.8 ± 1.6 | 3.1 ± 0.7 186.1 ± 84.7 ¶ 108.3 ± 14.5 89.2 ± 4.8 ¶ 4.6 ± 1.4 | 3.3 ± 0.8 175.6 ± 88.7 108.6 ± 13.3 88.1 ± 5.9 4.9 ± 1.6 | 3.2 ± 1.2 171.1 ± 105.2 * 108.0 ± 14.9 87.6 ± 5.4 * 4.9 ± 1.6 |

| 6MWT 6MWD, metres (62) 6MWD, %pred (62) End saturation (%) (60) Numbers of pauses during test (60) End Borg CR-10 score (60) | 299.1 ± 87.2 50 ± 15 88.3 ± 5.0 1.1 ± 1.4 5.1 ± 1.7 | 259.3 ± 64.8 ¶ 44 ± 10 ¶ 89.8 ± 4.2 1.5 ± 1.4 5.2 ± 1.7 | 272.2 ± 98.8 ¶ 48 ± 19 89.6 ± 4.0 1.1 ± 1.4 5.4 ± 1.8 | 330.6 ± 76.1 * # 55 ± 13 * 86.8 ± 5.5 0.9 ± 1.5 4.9 ± 1.7 | 268.3 ± 58.9 42 ± 11 ¶ 93.0 ± 6.1 1.0 ± 1.0 4.3 ± 0.6 | 272.6 ± 108.5 47 ± 17 89.9 ± 4.3 1.1 ± 1.1 5.1 ± 2.1 | 306.5 ± 93.6 53 ± 14 * 86.1 ± 5.1 0.6 ± 1.0 5.6 ± 1.5 |

| SGRQ total score (652) Symptom score (652) Activity score (652) Impact score (652) | 54.2 ± 13.3 60.7 ± 19.5 75.8 ± 14.5 40.1 ± 15.8 | 58.9 ± 12.9 ¶ 66.6 ± 17.9# ¶ 77.8 ± 15.1 ¶ 46.3 ± 5.7 # ¶ | 55.8 ± 13.3 ¶ 62.0 ± 19.3 * ¶ 77.4 ± 14.9 ¶ 41.8 ± 15.4 * ¶ | 51.0 ± 12.7 * # 57.2 ± 19.7 * # 73.8 ± 13.8 * # 36.3 ± 15.3 * # | 56.7 ± 13.4 ¶ 64.2 ± 18.7 ¶ 77.8 ± 15.1 ¶ 42.5 ± 16.7 ¶ | 56.2 ± 12.8 ¶ 63.5 ± 17.7 ¶ 77.4 ± 13.7 ¶ 42.3 ± 15.0 ¶ | 51.7 ± 12.6 * # 58.2 ± 19.7 * # 74.0 ± 14.6 * # 37.2 ± 15.2 * # |

| CAT score (274) | 18.7 ± 6.7 | 23.2 ± 5.3 # ¶ | 19.5 ± 6.1 * ¶ | 17.4 ± 6.8 * # | 22.1 ± 5.1 ¶ | 20.1 ± 6.1 ¶ | 15.7 ± 6.3 * # |

| Response from Baseline to 10 Weeks (Post-Intervention) | Response from Baseline to One-Year Follow-Up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interval 2002–2011 (n = 647) | Interval 2012–2019 (n = 275) | Interval 2002–2011 (n = 647) | Interval 2012–2019 (n = 275) | |

| Full Responder, n (%) | 108 (16.7) * | 31 (11.3) | 98 (17.5) * | 16 (8.2) |

| Responder, n (%) | 253 (39.1) * | 92 (33.5) | 198 (35.4) | 81 (41.5) |

| Non-Responder, n (%) | 286 (44.2) * | 152 (55.3) | 264 (47.1) * | 98 (50.3) |

| Full Responders | Responders | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds Ratio (Confidence Interval) | p-Value | Odds Ratio (Confidence Interval) | p-Value | |

| 10-week follow-up (adjusted for ESWT) (n = 701) | ESWT | 1.003 (1.000–1.005) | 0.020 * | 1.002 (1.000–1.004) | 0.045 * |

| Sex | 0.915 (0.566–1.479) | 0.717 | 0.941 (0.656–1.349) | 0.741 | |

| Age | 0.976 (0.951–1.002) | 0.069 | 0.980 (0.961–0.999) | 0.044 * | |

| FEV1 | 0.994 (0.975–1.014) | 0.561 | 1.004 (0.990–1.018) | 0.605 | |

| BMI | 0.970 (0.931–1.011) | 0.150 | 0.988 (0.960–1.016) | 0.560 | |

| Marital status | 0.790 (0.494–1.261) | 0.322 | 1.273 (0.900–1.800) | 0.173 | |

| 10-week follow-up (adjusted for 6MWT) (n = 39) | 6MWT | 0.994 (0.983–1.006) | 0.326 | 0.989 (0.980–0.999) | 0.024 * |

| Sex | 0.148 (0.011–2.075) | 0.156 | 0.517 (0.095–2.806) | 0.444 | |

| Age | 1.034 (0.865–1.236) | 0.711 | 1.001 (0.874–1.148) | 0.984 | |

| FEV1 | 1.025 (0.920–1.142) | 0.651 | 1.009 (0.931–1.095) | 0.820 | |

| BMI | 0.991 (0.802–1.223) | 0.930 | 1.092 (0.951–1.254) | 0.214 | |

| Marital status | 1.210 (0.117–12.471) | 0.873 | 0.472 (0.086–2.597) | 0.388 | |

| 10-week follow-up (adjusted for SGRQ) (n = 552) | SGRQ | 1.040 (1.020–1.061) | <0.001 * | 1.026 (1.011–1.041) | <0.001 * |

| Sex | 0.954 (0.556–1.639) | 0.865 | 0.842 (0.556–1.274) | 0.416 | |

| Age | 0.980 (0.952–1.010) | 0.183 | 0.972 (0.950–0.994) | 0.014 * | |

| FEV1 | 0.998 (0.977–1.019) | 0.819 | 1.010 (0.995–1.025) | 0.194 | |

| BMI | 0.970 (0.926–1.015) | 0.187 | 0.987 (0.955–1.021) | 0.456 | |

| Marital status | 0.576 (0.342–0.970) | 0.038 * | 1.084 (0.728–1.616) | 0.691 | |

| 10-week follow-up (adjusted for CAT) (n = 189) | CAT | 1.191 (1.076–1.319) | <0.001 * | 1.042 (0.988–1.100) | 0.131 |

| Sex | 0.300 (0.093–0.967) | 0.044 * | 0.951 (0.476–1.900) | 0.888 | |

| Age | 1.019 (0.953–1.090) | 0.583 | 1.034 (0.992–1.079) | 0.115 | |

| FEV1 | 1.023 (0.969–1.080) | 0.403 | 1.002 (0.969–1.036) | 0.897 | |

| BMI | 0.916 (0.823–1.018) | 0.101 | 0.994 (0.943–1.048) | 0.830 | |

| Marital status | 1.688 (0.540–5.272) | 0.368 | 1.235 (0.626–2.439) | 0.542 | |

| Full Responders | Responders | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds Ratio (Confidence Interval) | p-Value | Odds Ratio (Confidence Interval) | p-Value | |

| One-year follow-up (adjusted for ESWT) (n = 701) | ESWT | 1.001 (0.999–1.003) | 0.240 | 1.000 (0.999–1.002) | 0.682 |

| Sex | 0.928 (0.577–1.490) | 0.756 | 0.870 (0.607–1.247) | 0.449 | |

| Age | 0.953 (0.929–0.977) | 0.016 * | 0.974 (0.955–0.994) | 0.010 * | |

| FEV1 | 1.017 (0.998–1.035) | 0.078 | 1.015 (1.001–1.029) | 0.039 * | |

| BMI | 0.991 (0.954–1.030) | 0.658 | 0.996 (0.967–1.025) | 0.767 | |

| Marital status | 0.816 (0.516–1.291) | 0.386 | 1.041 (0.736–1.472) | 0.820 | |

| One-year follow-up (adjusted for 6MWT) (n = 39) | 6MWT | 0.991 (0.977–1.005) | 0.220 | 0.990 (0.981–1.000) | 0.055 |

| Sex | 0.086 (0.003–2.217) | 0.139 | 0.048 (0.005–0.501) | 0.011 * | |

| Age | 0.877 (0.667–1.153) | 0.347 | 1.059 (0.904–1.240) | 0.479 | |

| FEV1 | 1.019 (0.876–1.185) | 0.808 | 1.062 (0.969–1.164) | 0.200 | |

| BMI | 0.945 (0.746–1.197) | 0.638 | 1.069 (0.915–1.249) | 0.399 | |

| Marital status | 5.793 (0.279–120.059) | 0.256 | 4.949 (0.550–44.509) | 0.154 | |

| One-year follow-up (adjusted for SGRQ) (n = 552) | SGRQ | 1.028 (1.009–1.048) | 0.003 * | 1.027 (1.012–1.043) | <0.001 * |

| Sex | 1.002 (0.594–1.692) | 0.993 | 0.874 (0.574–1.331) | 0.530 | |

| Age | 0.955 (0.928–0.982) | 0.001 * | 0.975 (0.953–0.998) | 0.036 * | |

| FEV1 | 1.021 (1.001–1.040) | 0.038 * | 1.019 (1.003–1.035) | 0.018 * | |

| BMI | 0.988 (0.948–1.031) | 0.583 | 0.986 (0.953–1.021) | 0.437 | |

| Marital status | 0.687 (0.416–1.134) | 0.142 | 0.907 (0.605–1.357) | 0.634 | |

| One-year follow-up (adjusted for CAT) (n = 189) | CAT | 1.169 (1.055–1.295) | 0.003 * | 1.113 (1.053–1.177) | <0.001 * |

| Sex | 0.322 (0.098–1.064) | 0.063 | 0.567 (0.287–1.119) | 0.102 | |

| Age | 0.987 (0.923–1.057) | 0.716 | 1.019 (0.979–1.062) | 0.354 | |

| FEV1 | 1.012 (0.955–1.073) | 0.678 | 1.011 (0.978–1.045) | 0.526 | |

| BMI | 0.952 (0.860–1.054) | 0.343 | 1.007 (0.956–1.061) | 0.787 | |

| Marital status | 1.500 (0.457–4.923) | 0.503 | 1.454 (0.741–2.853) | 0.277 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Van Raemdonck, I.; van Waterschoot, J.; Vanuytrecht, Y.; Vissers, D.; Lapperre, T.; Hansen, H. Short- and Long-Term Responses to Pulmonary Rehabilitation in 922 Patients with COPD: A Real-World Database Study (2002–2019). J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020793

Van Raemdonck I, van Waterschoot J, Vanuytrecht Y, Vissers D, Lapperre T, Hansen H. Short- and Long-Term Responses to Pulmonary Rehabilitation in 922 Patients with COPD: A Real-World Database Study (2002–2019). Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):793. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020793

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Raemdonck, Isis, Janne van Waterschoot, Yara Vanuytrecht, Dirk Vissers, Thérèse Lapperre, and Henrik Hansen. 2026. "Short- and Long-Term Responses to Pulmonary Rehabilitation in 922 Patients with COPD: A Real-World Database Study (2002–2019)" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020793

APA StyleVan Raemdonck, I., van Waterschoot, J., Vanuytrecht, Y., Vissers, D., Lapperre, T., & Hansen, H. (2026). Short- and Long-Term Responses to Pulmonary Rehabilitation in 922 Patients with COPD: A Real-World Database Study (2002–2019). Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020793