Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint (SATMJ) in Adults: A Systematic Review of Case Reports and Case Series, Part I: Etiology and Epidemiology

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Rationale

1.3. Objectives

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Selection Process

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Data Items

2.7. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.8. Statistical Methods

2.9. Certainty Assessment

3. Results

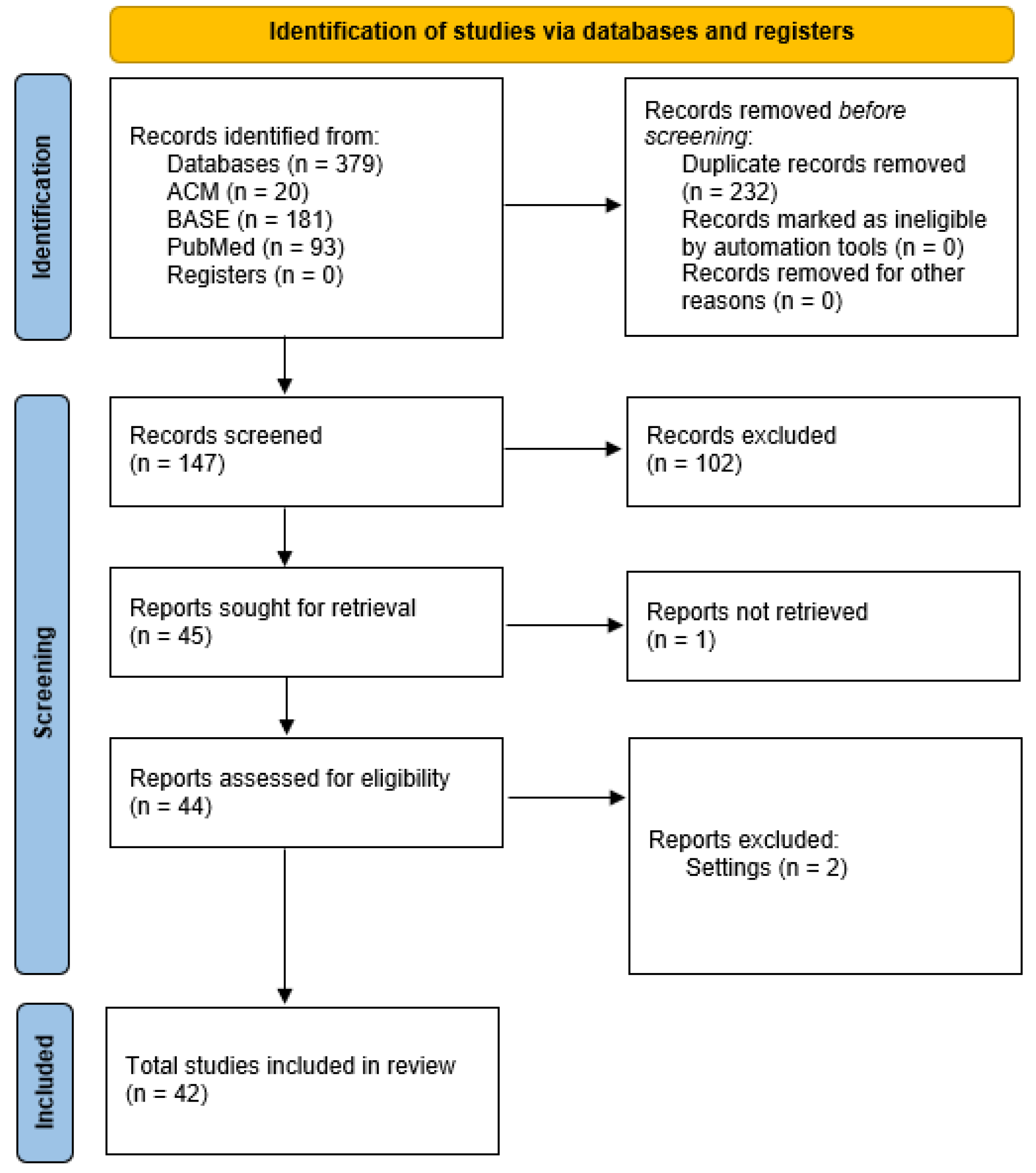

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

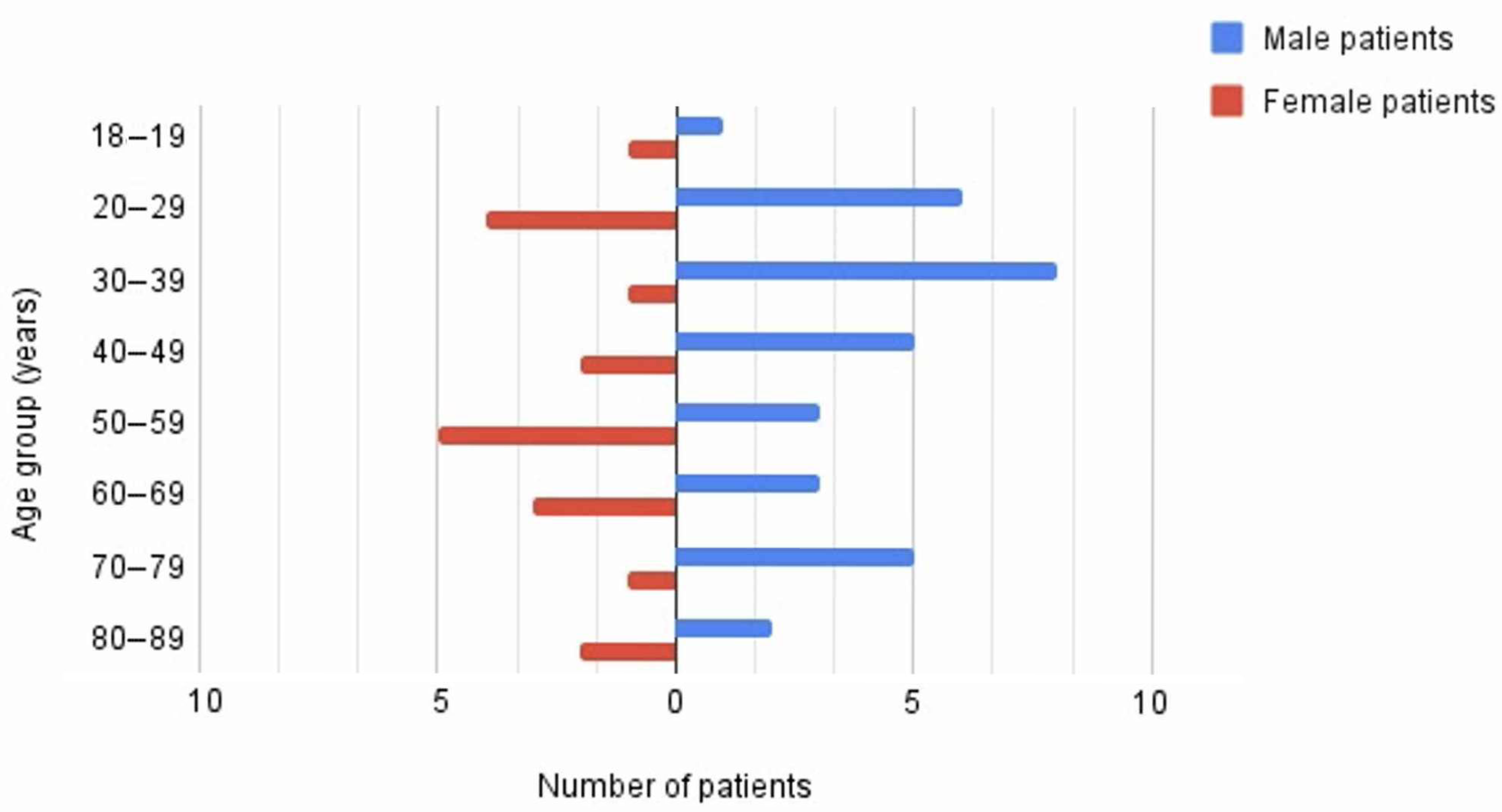

3.5. Result of Syntheses

4. Discussion

4.1. General Interpretation of the Results

4.2. Strengths

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Applicability and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| First Author, Publication Year | DOI | Age | Sex | Affected TMJs | Presented Bacteria | Systemic Disease | Ear Diseases | Preauricular Area Disease, Injury, or Treatment | Surgical Treatment | Oral Health Issues | Other Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Khalisy, 2015 [18] | https://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.168678 | 24 | M | 1 | Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus | N/S | N/A | N/S | N/S | N/A | N/A |

| Ângelo, 2023 [19] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2023.06.008 | 68 | M | 1 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Diabetes, immunosuppressive treatment | N/A | Chronic purulent otitis media | N/S | N/A | N/A |

| Araz Server, 2017 [20] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2017.04.007 | 55 | F | 1 | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | Diabetes | N/A | N/S | N/S | Peritonsillar abscess, Tonsillitis | N/A |

| Baniel, 2020 [21] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.07.006 | 85 | F | 1 | MRSA | N/S | N/A | N/S | N/S | N/A | N/A |

| Bounds, 1987 [22] | https://doi.org/10.1016/0266-4356(87)90158-6 | 72 | F | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | N/S | N/A | Fracture of the posterior wall of the temporomandibular joint into the external auditory meatus | N/S | N/A | Chin trauma |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060 | 48 | M | 1 | Gram-positive coccus | N/S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060 | 26 | F | 1 | Staphylococcus saprophyticus | N/S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060 | 22 | F | 1 | Gram-positive coccus | N/S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060 | 30 | M | 1 | Gram-positive coccus | N/S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060 | 19 | F | 1 | Gram-positive coccus | N/S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060 | 46 | M | 1 | Staphylococcus saprophyticus | N/S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060 | 25 | M | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | N/S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060 | 54 | M | 1 | N/S | N/A | N/A | Osteoarthritis | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060 | 21 | F | 1 | N/S | N/A | N/A | Fibrosis | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060 | 45 | M | 1 | Gram-positive coccus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060 | 40 | F | 1 | Staphylococcus saprophyticus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060 | 37 | M | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060 | 63 | M | 1 | Gram-positive coccus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cheong, 2017 [24] | https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3641642 | 76 | M | 1 | Achromobacter xylosoxidans | N/A | Acute otitis media | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Dias Ferraz, 2021 [25] | https://doi.org/10.1080/08869634.2019.1661943 | 64 | F | 1 | Pseudomonas spp. | N/A | N/A | Mandible angle fracture | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Dias Ferraz, 2021 [25] | https://doi.org/10.1080/08869634.2019.1661943 | 34 | M | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Odontogenic abscess, III molar extraction | N/A |

| Dias Ferraz, 2021 [25] | https://doi.org/10.1080/08869634.2019.1661943 | 21 | M | 1 | Streptococcus group D | Asthma | N/A | N/A | N/A | Odontogenic abscess | N/A |

| Døving, 2021 [26] | https://doi.org/10.1007/s10006-020-00921-z | 72 | M | 1 | Streptococcus constellatus Dialister pneumosintes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Gams, 2016 [27] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2015.11.003 | 25 | M | 1 | Bacteroides uniformis | Diabetes | N/A | N/S | N/A | Odontogenic infection | N/A |

| Gayle, 2013 [28] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.01.034 | 18 | F | 1 | Staphylococcus, Group C Streptococcus, and Acinetobacter baumannii | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Granadas, 2023 [29] | https://doi.org/10.35100/eurorad/case.18139 | 59 | F | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Hincapie, 1999 [30] | https://doi.org/10.1053/hn.1999.v121.a96115 | 33 | M | 1 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Ishikawa, 2017 [31] | https://doi.org/10.1007/s10006-016-0604-z | 87 | M | 1 | MRSA | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kim, 2011 [32] | https://doi.org/10.5125/jkaoms.2011.37.6.510 | 46 | M | 1 | Alpha streptococci species | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kim, 2011 [32] | https://doi.org/10.5125/jkaoms.2011.37.6.510 | 43 | F | 1 | Alpha streptococci species | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kim, 2019 [33] | https://doi.org/10.14476/jomp.2019.44.3.127 | 49 | M | 1 | Haemophilus aphrophilus | Diabetes | N/A | N/S | Trigeminal nerve block treatment | N/A | N/A |

| Klüppel, 2012 [34] | https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182646061 | 58 | F | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Levorova, 2017 [35] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2016.09.008 | 38 | F | 1 | Raoultella ornithinolytica | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Lohiya, 2016 [36] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2015.06.166 | 56 | F | 1 | Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus aureus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Lohiya, 2016 [36] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2015.06.166 | 49 | M | 1 | MRSA | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Moses, 1998 [37] | https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-2391(98)90725-X | 36 | M | 1 | Streptococcus anginosus, Streptococcus viridans, | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Nagarakanti, 2020 [38] | https://doi.org/10.1177/0145561320944648 | 58 | M | 1 | MSSA Candida glabrata | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Oliveira, 2024 [39] | https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.64480 | 61 | F | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Sembronio, 2007 [40] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.08.028 | 52 | F | 1 | Streptococcus sp. | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Suda, 2017 [41] | https://doi.org/10.4236/ojst.2017.74018 | 85 | M | 1 | Propionibacterium spp. Veillonella spp. | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Thakur, 2022 [42] | https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2021-247111 | Late 30 s | M | 1 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Thomson, 1989 [43] | https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022215100108813 | 59 | F | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Thomson, 1989 [43] | https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022215100108813 | 70 | M | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Trimble, 1983 [44] | https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-0503(83)80022-8 | 53 | F | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Turton, 2022 [45] | https://doi.org/10.1007/s12663-021-01637-7 | 18 | M | 1 | Fusobacterium necrophorum | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Varghese, 2015 [46] | PMID: 25738723 | 74 | M | 1 | Aspergillus flavus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Xiao, 2017 [47] | https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2017.4510 | 83 | F | 1 | Escherichia coli | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Yang, 2016 [48] | https://doi.org/10.5125/jkaoms.2016.42.4.227 | 52 | M | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Metzger, 1970 [49] | https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-73-2-267- | 23 | M | 1 | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Mumps | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Sore throat |

| Alexander, 1973 [50] | https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(73)90331-9 | 21 | M | 1 | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Granuloma, hard drug use |

| Winters, 1955 [51] | https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(55)90185-7 | 19 | M | 1 | Staphylococcus albus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Seymour, 1982 [52] | https://doi.org/10.1016/S0007-117X(82)80021-8 | 19 | F | 1 | Haemophilus influenzae | Arthritis | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Upper respiratory tract infection |

| Goldschmidt, 2002 [53] | https://doi.org/10.1053/joms.2002.35736 | 35 | M | 1 | Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Pharyngitis, HBV, HCV, cocaine user, venereal disease |

| Enomoto, 2012 [54] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2011.06.215 | 70 | M | 1 | Prevotella, Haemophilus, Streptococcus | Prostate carcinoma | N/A | N/A | N/A | Pericoronitis, periapical lesion of II/III mola | Bisphosphonates therapy |

| Vongsfak, 2020 [55] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inat.2020.100709 | 65 | F | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Subgaleal abscess |

| Noroy, 2020 [56] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2019.09.010 | 68 | M | 1 | Aspergillus flavus, Staphylococcus epidermidis | Diabetes | Otitis externa | N/A | N/A | N/A | Papillary renal cell carcinoma |

| Chue, 1975 [57] | https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(75)90198-X | 27 | F | 1 | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Acute gonorrhea |

| Murakami, 1984 [58] | https://doi.org/10.1016/s0301-0503(84)80209-x | 43 | M | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Periapical lesion | N/A |

| Hilbert, 1984 [59] | https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-4179(84)90032-9 | 37 | M | 1 | N/A | N/A | Otitis externa | N/A | N/A | N/A | 24% third degree burns |

| First Author, Publication Year | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | Favorable (“Yes”) Answers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomson, 1989 [43] | No | Unclear | No | No | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | N/A | 2 |

| Kim, 2011 [32] | No | Yes | No | No | No | Unclear | No | Yes | No | N/A | 2 |

| Lohiya, 2016 [36] | No | Yes | No | No | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | N/A | 3 |

| Gayle, 2013 [28] | No | Yes | No | No | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | N/A | 3 |

| Dias Ferraz, 2021 [25] | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | N/A | 5 |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| First Author, Publication Year | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | Favorable (“Yes”) Answers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Khalisy, 2015 [18] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Ângelo, 2023 [19] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Sembronio, 2007 [40] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Hincapie, 1999 [30] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | No | Yes | 5 |

| Moses, 1998 [37] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Døving, 2021 [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Gams, 2016 [27] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Granadas, 2023 [29] | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| Ishikawa, 2017 [31] | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | 5 |

| Levorova, 2017 [35] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Kim, 2019 [33] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | 6 |

| Klüppel, 2012 [34] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Nagarakanti, 2020 [38] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | 6 |

| Oliveira, 2024 [39] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | 6 |

| Araz Server, 2017 [20] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Suda, 2017 [41] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Yang, 2016 [48] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Varghese, 2015 [46] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Baniel, 2020 [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Bounds, 1987 [22] | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | 4 |

| Cheong, 2017 [24] | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Thakur, 2022 [42] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Trimble, 1983 [44] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | 6 |

| Turton, 2022 [45] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Xiao, 2017 [47] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Murakami, 1984 [58] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | No | Yes | 4 |

| Hilbert, 1984 [59] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Metzger, 1970 [49] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Winters, 1955 [51] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | 6 |

| Alexander, 1973 [50] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Chue, 1975 [57] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| Seymour, 1982 [52] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Goldschmidt, 2002 [53] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Enomoto, 2012 [54] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Vongsfak, 2020 [55] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | 7 |

| Noroy, 2020 [56] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 7 |

| First Author, Publication Year | Sex (F:0/M:1) | Age | Anaerobic or Relatively Anaerobic Infection (0/1) | Aerobic Infection (0/1) | Gram (−) Infection (0/1) | Gram (+) Infection (0/1) | Fungal SATMJ (0/1) | Odontogenic Problem (0/1) | Previous Surgery and/or Trauma (0/1) | Local, Non-Odontogenic Infection (0/1) | Diabetes (0/1) | Immunoincompetence (0/1) | Systemic Disease (0/1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Khalisy, 2015 [18] | 1 | 24 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Ângelo, 2023 [19] | 1 | 68 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Araz Server, 2017 [20] | 0 | 55 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Baniel, 2020 [21] | 0 | 85 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Bounds, 1987 [22] | 0 | 72 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | 1 | 48 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | 0 | 26 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | 0 | 22 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | 1 | 30 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | 0 | 19 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | 1 | 46 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | 1 | 25 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | 1 | 54 | N/S | N/S | N/S | N/S | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | 0 | 21 | N/S | N/S | N/S | N/S | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | 1 | 45 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | 0 | 40 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | 1 | 37 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cai, 2010 [23] | 1 | 63 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cheong, 2017 [24] | 1 | 76 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dias Ferraz, 2021 [25] | 0 | 64 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Dias Ferraz, 2021 [25] | 1 | 34 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dias Ferraz, 2021 [25] | 1 | 21 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Døving, 2021 [26] | 1 | 72 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Gams, 2016 [27] | 1 | 25 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Gayle, 2013 [28] | 0 | 18 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Granadas, 2023 [29] | 0 | 59 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Hincapie, 1999 [30] | 1 | 33 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Ishikawa, 2017 [31] | 1 | 87 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kim, 2011 [32] | 1 | 46 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kim, 2011 [32] | 0 | 43 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kim, 2019 [33] | 1 | 49 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Klüppel, 2012 [34] | 0 | 58 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Levorova, 2017 [35] | 0 | 38 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Lohiya, 2016 [36] | 0 | 56 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Lohiya, 2016 [36] | 1 | 49 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Moses, 1998 [37] | 1 | 36 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Nagarakanti, 2020 [38] | 1 | 58 | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Oliveira, 2024 [39] | 0 | 61 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Sembronio, 2007 [40] | 0 | 52 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Suda, 2017 [41] | 1 | 85 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Thakur, 2022 [42] | 1 | 38 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Thomson, 1989 [43] | 0 | 59 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Thomson, 1989 [43] | 1 | 70 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Trimble, 1983 [44] | 0 | 53 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Turton, 2022 [45] | 1 | 18 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Varghese, 2015 [46] | 1 | 74 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Xiao, 2017 [47] | 0 | 83 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Yang, 2016 [48] | 1 | 52 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Metzger, 1970 [49] | 1 | 23 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Alexander, 1973 [50] | 1 | 21 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Winters, 1955 [51] | 1 | 19 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Seymour, 1982 [52] | 0 | 19 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Goldschmidt, 2002 [53] | 1 | 35 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Enomoto, 2012 [54] | 1 | 70 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Vongsfak, 2020 [55] | 0 | 65 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Murakami, 1984 [58] | 1 | 43 | N/S | N/S | N/S | N/S | N/S | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Hilbert, 1984 [59] | 1 | 37 | N/S | N/S | N/S | N/S | N/S | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Noroy, 2020 [56] | 1 | 68 | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Chue, 1975 [57] | 0 | 27 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

References

- Alomar, X.; Medrano, J.; Cabratosa, J.; Clavero, J.A.; Lorente, M.; Serra, I.; Monill, J.M.; Salvador, A. Anatomy of the Temporomandibular Joint. Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI 2007, 28, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Drangsholt, M.; Peck, C.; Sato, H.; Kopp, S.; Svensson, P. Topical Review: New Insights into the Pathology and Diagnosis of Disorders of the Temporomandibular Joint. J. Orofac. Pain 2004, 18, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choukas, N.C.; Sicher, H. The Structure of the Temporomandibular Joint. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1960, 13, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkie, G.; Al-Ani, Z. Temporomandibular Joint Anatomy, Function and Clinical Relevance. Br. Dent. J. 2022, 233, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halabitska, I.; Babinets, L.; Oksenych, V.; Kamyshnyi, O. Diabetes and Osteoarthritis: Exploring the Interactions and Therapeutic Implications of Insulin, Metformin, and GLP-1-Based Interventions. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-T.; Wu, C.-D.; Cheng, S.-C.; Chiu, C.-C.; Tseng, C.-C.; Chan, H.-T.; Chen, P.-Y.; Chao, C.-M. High Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus among Patients with Septic Arthritis Caused by Staphylococcus Aureus. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haertlé, M.; Kolbeck, L.; Macke, C.; Graulich, T.; Stauß, R.; Omar, M. Diagnostic Accuracy for Periprosthetic Joint Infection Does Not Improve by a Combined Use of Glucose and Leukocyte Esterase Strip Reading as Diagnostic Parameters. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubecka, K.; Galant, K.; Chęciński, M.; Chęcińska, K.; Bliźniak, F.; Ciosek, A.; Gładysz, T.; Cholewa-Kowalska, K.; Chlubek, D.; Sikora, M. A Protocol for a Systematic Review on Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint (SATMJ). J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayachi, S.; Mziou, Z.; Moatemri, R.; Khochtali, H. Bilateral Septic Arthritis of the Temporo Mandibular Joint: Case Report. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016, 25, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, N.S.; Mohamad, N.; Razali, N.A.; Zamli, A.K.T.; Sapiai, N.A. Septic Arthritis of Temporomandibular Joint. Med. J. Malays. 2021, 76, 264–266. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, E.F.R.; Fernandes, G.; Ongaro, P.C.J.; Campi, L.B.; Gonçalves, D.A.G. Systemic Diseases and Other Painful Conditions in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders and Migraine. Braz. Oral Res. 2018, 32, e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahim-Williams, B.; Tomar, S.; Blanchard, S.; Riley, J.L. Influences of Adult-Onset Diabetes on Orofacial Pain and Related Health Behaviors. J. Public Health Dent. 2010, 70, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wen, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, B.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, L. Hyperglycemia-Induced Accumulation of Advanced Glycosylation End Products in Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes Promotes Knee Osteoarthritis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 1735–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Gao, Z.; Xiao, H.; Qian, Y.; Fan, R.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Yang, Y.; Qiao, Y. Energy Metabolism Dysfunction and Therapeutic Strategies for Treating Temporomandibular Disorders. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1581446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berbudi, A.; Rahmadika, N.; Tjahjadi, A.I.; Ruslami, R. Type 2 Diabetes and Its Impact on the Immune System. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2020, 16, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Lansang, M.C. Diabetes Mellitus and Infection. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., et al., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalisy, H.; Nikiforov, I.; Mansoora, Q.; Goldman, J.; Cheriyath, P. Septic Arthritis in the Temporomandibular Joint. North Am. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 7, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ângelo, D.F.; Mota, B.; Sanz, D.; Pimentel, J. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint Managed with Arthroscopy: A Case Report. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 52, 1278–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araz Server, E.; Onerci Celebi, O.; Hamit, B.; Yigit, O. A Rare Complication of Tonsillitis: Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 1118–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniel, C.; Kennedy, T.A.; Ciske, D.J. A Report of Antibiotic-Treated, Blood-Culture Negative MRSA Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint Preceding MRSA Epidural Abscess. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, e13–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounds, G.A.; Hopkins, R.; Sugar, A. Septic Arthritis of the Temporo-Mandibular Joint—A Problematic Diagnosis. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1987, 25, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.-Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Qiu, W.-L.; Chen, M.-J.; Zhang, S.-Y. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint: A Retrospective Review of 40 Cases. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 68, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, R.C.T.; Harding, L. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint Secondary to Acute Otitis Media in an Adult: A Rare Case with Achromobacter xylosoxidans. Case Rep. Otolaryngol. 2017, 2017, 3641642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias Ferraz, A.; Spagnol, G.; Maciel, F.A.; Pinotti, M.M.; De Freitas, R.R. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint: Case Series and Literature Review. Cranio 2021, 39, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Døving, M.; Christensen, E.E.; Huse, L.P.; Vengen, Ø. A Case of Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint with Necrotic Peri-Articular Infection and Lemierre’s Syndrome: An Unusual Presentation. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 25, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gams, K.; Freeman, P. Temporomandibular Joint Septic Arthritis and Mandibular Osteomyelitis Arising from an Odontogenic Infection: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 74, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayle, E.A.; Young, S.M.; McKenna, S.J.; McNaughton, C.D. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint: Case Reports and Review of the Literature. J. Emerg. Med. 2013, 45, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granadas, J. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint Assessed by US and CT. 2023. Available online: https://www.eurorad.org/case/18139 (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Hincapie, J.W.; Tobon, D.; Diaz-Reyes, G.A. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 1999, 121, 836–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, S.; Watanabe, T.; Iino, M. Acute Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint Derived from Otitis Media: A Report and Review of the English and Japanese Literature. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 21, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-M.; Kim, T.-W.; Hwang, J.-H.; Lee, D.-J.; Park, N.-R.; Song, S.-I. Infection of the Temporomandibular Joint: A Report of Three Cases. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 37, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Choi, H.-W.; Kim, J.-Y.; Park, K.-H.; Huh, J.-K. Differential Diagnosis and Treatment of Septic Arthritis in the Temporomandibular Joint: A Case Report and Literature Review. J. Oral Med. Pain 2019, 44, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klüppel, L.E.; Bernabé, F.B.R.; Primo, B.T.; Stringhini, D.J.; Da Costa, D.J.; Rebellato, N.L.B.; Müller, P.R. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2012, 23, 1752–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levorova, J.; Machon, V.; Guha, A.; Foltan, R. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint Caused by Rare Bacteria Raoultella Ornithinolytica. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohiya, S.; Dillon, J. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint—Unusual Presentations. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 74, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, J.J.; Lange, C.R.; Arredondo, A. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint after the Removal of Third Molars. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1998, 56, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarakanti, S.R.; Bishburg, E.; Grinberg, S. Mastoiditis, Osteomyelitis, and Septic Arthritis of Temporomandibular Joint. Ear Nose Throat J. 2022, 101, 81–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.; Mesquita, M.; Correia, S.; Colino, M. The Importance of Early Diagnosis and Treatment in Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e64480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembronio, S.; Albiero, A.M.; Robiony, M.; Costa, F.; Toro, C.; Politi, M. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint Successfully Treated with Arthroscopic Lysis and Lavage: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol 2007, 103, e1–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, D.; Takatsuji, H.; Saito, N.; Funayama, A.; Niimi, K.; Kobayashi, T. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint without an Apparent Source of Infection: A Case Report. Open J. Stomatol. 2017, 07, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thakur, N.; Negi, S.; Thakur, J.S.; Arora, R.D. Peritonsillar Abscess Due to Temporomandibular Joint Septic Arthritis: An Uncommon Cause of a Common Disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2022, 15, e247111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, H.G. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint Complicating Otitis Externa. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1989, 103, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble, L.D.; Schoenaers, J.A.H.; Stoelinga, P.J.W. Acute Suppurative Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint in a Patient with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 1983, 11, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turton, N.; McGoldrick, D.M.; Walker, K.; Martin, T.; Praveen, P. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint with Intracranial Extension: A Case Report. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2022, 21, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, L.; Chacko, R.; Varghese, G.M.; Job, A. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint Caused by Aspergillus Flavus Infection as a Complication of Otitis Externa. Ear Nose Throat J. 2015, 94, E24. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, D.; Feng, X.; Huang, H.; Quan, H. Severe Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint with Pyogenic Orofacial Infections: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, S.-W.; Cho, J.-Y.; Kim, H.-M. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint: A Case Report. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 42, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, A.L. Gonococcal Arthritis Complicating Gonorrheal Pharyngitis. Ann. Intern. Med. 1970, 73, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, W.N.; Nagy, W.W. Gonococcal Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1973, 36, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, S.E. Staphylococcus Infection of the Temporomandibular Joint. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1955, 8, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, R.A.; Summersgill, G.B. Haemophilus Influenzae Pyarthrosis in a Young Adult with Subsequent Temporomandibular Joint Involvement. Br. J. Oral Surg. 1982, 20, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschmidt, M.J.; Butterfield, K.J.; Goracy, E.S.; Goldberg, M.H. Streptococcal Infection of the Temporomandibular Joint of Hematogenous Origin: A Case Report and Contemporary Therapy. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2002, 60, 1347–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enomoto, A.; Uchihashi, T.; Izumoto, T.; Nakahara, H.; Hamada, S. Suppurative Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint Associated with Bisphosphonate: A Case Report. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70, 1376–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongsfak, J.; Klibngern, H. Case Report Rare Complication of Temporomandibular Joint Infection: Subgaleal Abscess. Interdiscip. Neurosurg. 2020, 21, 100709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroy, L.; Pujo, K.; Leghzali-Moise, H.; Saison, J. Aspergillus Necrotizing Otitis Externa with Temporomandibulozygomatic Involvement. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2020, 137, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chue, P.W.Y. Gonococcal Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1975, 39, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Iizuka, T. Suppurative Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 1984, 12, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, L.; Peters, W.J.; Tepperman, P.S. Temporomandibular Joint Destruction after a Burn. Burns 1984, 10, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Condition | Glucose Concentration in Blood (mg/dL) | Glucose Concentration in Synovial Fluid (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|

| Euglycemia | 70–100 | 60–95 |

| Mild hyperglycemia (prediabetes) | 100–125 | 90–120 |

| Hyperglycemia (diabetes) | ≥126 | 115–135 |

| Criteria for Inclusion | Criteria for Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | SATMJ cases with at least one risk factor or pathogen causing inflammation identified | Animal studies, cadaver studies, pediatric patients, |

| Intervention | Any conservative or surgical treatment | Treatment of a systemic disease only |

| Comparison | Not required | Not applicable |

| Outcomes—etiological factors | Demographics, systemic disease, local injury or disease, microbiological agent | Not applicable |

| Outcomes—diagnostics and treatment | Diagnostic methods used, conservative treatment, invasive treatment, hospitalization length, resolution and recurrences, complications | Not applicable |

| Settings | Primary studies, e.g., case series, case reports | Preprints, conference proceedings, book chapters, |

| Characteristic | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|

| Number of included publications | 42 |

| Total number of reported cases | 50+ (case reports and case series) |

| Publication years | 1955–2024 |

| Age (range) | 18–87 years |

| Sex distribution | Predominantly male |

| Affected temporomandibular joint | Unilateral involvement in all reported cases |

| Most frequently isolated pathogens | Staphylococcus aureus (most common), other Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp. |

| Gram-positive infections | Predominant |

| Gram-negative infections | Less frequent (e.g., Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Escherichia coli) |

| Fungal infections | Rare (mainly Aspergillus spp.) |

| Reported systemic diseases | Diabetes mellitus most frequent; malignancy and immunosuppression occasionally reported |

| Ear-related infections | Reported in a minority of cases (e.g., otitis media/externa) |

| Odontogenic or oropharyngeal source | Identified in a subset of cases |

| Previous surgery or trauma | Occasionally reported |

| Oral health–related factors | Sporadically reported |

| Other predisposing factors | Rare and heterogeneous |

| Study Design | Low Risk | Moderate Risk | High Risk | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case reports | 22 (61%) | 10 (28%) | 4 (11%) | 36 |

| Case series | 1 (17%) | 1 (17%) | 4 (66%) | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lubecka, K.; Galant, K.; Chęciński, M.; Chęcińska, K.; Bliźniak, F.; Ciosek, A.; Gładysz, T.; Cholewa-Kowalska, K.; Chlubek, D.; Sikora, M. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint (SATMJ) in Adults: A Systematic Review of Case Reports and Case Series, Part I: Etiology and Epidemiology. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 706. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020706

Lubecka K, Galant K, Chęciński M, Chęcińska K, Bliźniak F, Ciosek A, Gładysz T, Cholewa-Kowalska K, Chlubek D, Sikora M. Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint (SATMJ) in Adults: A Systematic Review of Case Reports and Case Series, Part I: Etiology and Epidemiology. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):706. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020706

Chicago/Turabian StyleLubecka, Karolina, Kacper Galant, Maciej Chęciński, Kamila Chęcińska, Filip Bliźniak, Agata Ciosek, Tomasz Gładysz, Katarzyna Cholewa-Kowalska, Dariusz Chlubek, and Maciej Sikora. 2026. "Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint (SATMJ) in Adults: A Systematic Review of Case Reports and Case Series, Part I: Etiology and Epidemiology" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 706. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020706

APA StyleLubecka, K., Galant, K., Chęciński, M., Chęcińska, K., Bliźniak, F., Ciosek, A., Gładysz, T., Cholewa-Kowalska, K., Chlubek, D., & Sikora, M. (2026). Septic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint (SATMJ) in Adults: A Systematic Review of Case Reports and Case Series, Part I: Etiology and Epidemiology. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 706. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020706