Comparison of Carotid Plaque Ultrasound and Computed Tomography in Patients and Ex Vivo Specimens—Agreement of Composition Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients, Carotid Endarterectomy, and Specimen Preparation

2.2. Computed Tomography

2.3. Ultrasound

2.4. Statistics and Comparative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Computed Tomography

3.2. Ultrasound

4. Discussion

4.1. Ultrasound: Dimensional Differences and the Need for Volumetric Ultrasound in Patients

4.2. CT: High Agreement and Remaining Limitations

4.3. Artificial Intelligence: Translational Potential of Quantitative Plaque Features Ex Vivo or In Vivo

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CCC | Lin’s Concordance Correlation Coefficient |

| CEA | Carotid Endarterectomy |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| DWA | Discrete White Areas |

| GS | Grayscale |

| GSM | Grayscale Median |

| HU | Hounsfield Unit |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| Phi (Φ) | Phi Correlation Coefficient |

| r | Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient |

| US | Ultrasound |

References

- Chang, R.W.; Tucker, L.Y.; Rothenberg, K.A.; Lancaster, E.; Faruqi, R.M.; Kuang, H.C.; Flint, A.C.; Avins, A.L.; Nguyen-Huynh, M.N. Incidence of Ischemic Stroke in Patients with Asymptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis Without Surgical Intervention. JAMA 2022, 327, 1974–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, H.H.; Kühnl, A.; Berkefeld, J.; Lawall, H.; Storck, M.; Sander, D. Webinar for S3 guideline “diagnosis, treatment, and aftercare of extracranial carotid stenosis”. Der Chir. 2021, 92, 383–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R.; Rantner, B.; Ancetti, S.; de Borst, G.J.; De Carlo, M.; Halliday, A.; Kakkos, S.K.; Markus, H.S.; McCabe, D.J.H.; Sillesen, H.; et al. Editor’s Choice—European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2023 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Atherosclerotic Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2023, 65, 7–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saba, L.; Cau, R.; Murgia, A.; Nicolaides, A.N.; Wintermark, M.; Castillo, M.; Staub, D.; Kakkos, S.K.; Yang, Q.; Paraskevas, K.I.; et al. Carotid Plaque-RADS: A Novel Stroke Risk Classification System. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 17, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brott, T.G.; Howard, G.; Lal, B.K.; Voeks, J.H.; Turan, T.N.; Roubin, G.S.; Lazar, R.M.; Brown, R.D., Jr.; Huston, J., 3rd; Edwards, L.J.; et al. Medical Management and Revascularization for Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisu, F.; Williamson, B.J.; Nardi, V.; Paraskevas, K.I.; Puig, J.; Vagal, A.; de Rubeis, G.; Porcu, M.; Cau, R.; Benson, J.C.; et al. Machine Learning Detects Symptomatic Plaques in Patients with Carotid Atherosclerosis on CT Angiography. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 17, e016274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisu, F.; Chen, H.; Jiang, B.; Zhu, G.; Usai, M.V.; Austermann, M.; Shehada, Y.; Johansson, E.; Suri, J.; Lanzino, G.; et al. Machine learning detects symptomatic patients with carotid plaques based on 6-type calcium configuration classification on CT angiography. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 3612–3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Weert, T.T.; Ouhlous, M.; Zondervan, P.E.; Hendriks, J.M.; Dippel, D.W.J.; van Sambeek, M.R.H.M.; van der Lugt, A. In vitro characterization of atherosclerotic carotid plaque with multidetector computed tomography and histopathological correlation. Eur. Radiol. 2005, 15, 1906–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzel, C.; Lell, M.; Maak, M.; Höckl, M.; Balzer, K.; Müller, K.M.; Fellner, C.; Fellner, F.A.; Lang, W. Carotid artery calcium: Accuracy of a calcium score by computed tomography-an in vitro study with comparison to sonography and histology. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2004, 28, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintermark, M.; Jawadi, S.S.; Rapp, J.H.; Tihan, T.; Tong, E.; Glidden, D.V.; Abedin, S.; Schaeffer, S.; Acevedo-Bolton, G.; Boudignon, B.; et al. High-resolution CT imaging of carotid artery atherosclerotic plaques. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2008, 29, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sztajzel, R.; Momjian, S.; Momjian-Mayor, I.; Murith, N.; Djebaili, K.; Boissard, G.; Comelli, M.; Pizolatto, G. Stratified gray-scale median analysis and color mapping of the carotid plaque: Correlation with endarterectomy specimen histology of 28 patients. Stroke 2005, 36, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridal, S.L.; Beyssen, B.; FoRnÈs, P.; Julia, P.; Berger, G. Multiparametric Attenuation and Backscatter Images for Characterization of Carotid Plaque. Ultrason. Imaging 2000, 22, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.; Taylor, P.; Poston, R.; Modaresi, K.; Padayachee, S. An objective method for grading ultrasound images of carotid artery plaques. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2001, 27, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingstone, L.L.; Shabana, W.; Chakraborty, S.; Kingstone, M.; Nguyen, T.; Thornhill, R.E.; Berthiaume, A.; Chatelain, R.; Currie, G. Vulnerable Carotid Artery Plaque Evaluation: Detection Agreement between Advanced Ultrasound, Computed Tomography, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Phantom Study. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2015, 46, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macharzina, R.R.; Stemmler, S.; Vach, W.; Winker, T.; Taron, J.; Schlett, C.L.; Weinbeck, M.; Siepe, M.; Czerny, M.; Bamberg, F.; et al. Ultra-high-resolution and dual-energy computed tomography of carotid artery plaques differentiate symptomatic and asymptomatic patients by novel volumetric analysis. Interdiscip. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2025, 40, ivaf158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannelli, L.; MacDonald, L.; Mancini, M.; Ferguson, M.; Shuman, W.P.; Ragucci, M.; Monti, S.; Xu, D.; Yuan, C.; Mitsumori, L.M. Dual energy computed tomography quantification of carotid plaques calcification: Comparison between monochromatic and polychromatic energies with pathology correlation. Eur. Radiol. 2015, 25, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M.; Heider, P.; Pelisek, J.; Poppert, H.; Eckstein, H.H. Ex vivo characterization of carotid plaques by intravascular ultrasonography and virtual histology: Concordance with real plaque pathomorphology. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 58, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, H.M.H.; Rasmussen, L.M.; Duvnjak, S.; Diederichsen, A.; Jensen, P.S.; Lindholt, J.S. Computed tomography scan based prediction of the vulnerable carotid plaque. BMC Med. Imaging 2017, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stemmler, S.; Zeller, T.; Westermann, D.; Czerny, M.; Soschynski, M.; Macharzina, R.R. Carotid plaque heterogeneity and lower calcified volume on computed tomography angiography are associated with neurologic symptoms. Clin. Radiol. 2026, 92, 107134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agatston, A.S.; Janowitz, W.R.; Hildner, F.J.; Zusmer, N.R.; Viamonte, M., Jr.; Detrano, R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1990, 15, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaides, A.N.; Kakkos, S.K.; Kyriacou, E.; Griffin, M.; Sabetai, M.; Thomas, D.J.; Tegos, T.; Geroulakos, G.; Labropoulos, N.; Doré, C.J. Asymptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis and cerebrovascular risk stratification. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010, 52, 1486–1496.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkos, S.K.; Griffin, M.B.; Nicolaides, A.N.; Kyriacou, E.; Sabetai, M.M.; Tegos, T.; Makris, G.C.; Thomas, D.J.; Geroulakos, G. The size of juxtaluminal hypoechoic area in ultrasound images of asymptomatic carotid plaques predicts the occurrence of stroke. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 57, 609–618.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.I. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics 1989, 45, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macharzina, R.R.; Kocher, S.; Messé, S.R.; Rutkowski, T.; Hoffmann, F.; Vogt, M.; Vach, W.; Fan, N.; Rastan, A.; Neumann, F.J.; et al. 4-Dimensionally Guided 3-Dimensional Color-Doppler Ultrasonography Quantifies Carotid Artery Stenosis with High Reproducibility and Accuracy. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, J.E.; Wichmann, J.L.; Bennett, D.W.; Leithner, D.; Bauer, R.W.; Vogl, T.J.; Bodelle, B. Detecting Intracranial Hemorrhage Using Automatic Tube Current Modulation with Advanced Modeled Iterative Reconstruction in Unenhanced Head Single- and Dual-Energy Dual-Source CT. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2017, 208, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter (Average ± SD) | Plaque | Patient | r a (CI b) | CCC c (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plaque volume (mm3) | 528 ± 292 | 754 ± 418 | 0.55 (0.43–0.65) | 0.43 (0.34–0.51) |

| Calcified volume (%) | 32.5 ± 20.7 | 40.3 ± 22.2 | 0.79 (0.72–0.84) | 0.74 (0.67–0.79) |

| Non-calcified volume (%) | 67.5 ± 20.7 | 59.7 ± 22.2 | 0.79 (0.72–0.84) | 0.74 (0.67–0.79) |

| Whole plaque average (HU d) | 456 ± 373 | 205 ± 154 | 0.79 (0.72–0.84) | 0.40 (0.37–0.43) |

| Whole plaque CV e | 1.6 ± 1.7 | 0.78 ± 0.51 | 0.16 (0.0–0.31) | 0.07 (0.0–0.14) |

| Calcified plaque average (HU) | 902 ± 284 | 357 ± 182 | 0.53 (0.40–0.64) | 0.13 (0.1–0.16) |

| Calcified plaque CV | 0.88 ± 0.50 | 0.48 ± 0.17 | 0.31 (0.16–0.45) | 0.12 (0.06–0.17) |

| Non-calcified plaque average (HU) | 59 ± 36.4 | 49 ± 35.0 | 0.34 (0.19–0.47) | 0.11 (0.06–0.15) |

| Non-calcified plaque CV | 0.82 ± 0.84 | 0.30 ± 0.32 | 0.15 (−0.01–0.31) | 0.07 (0.04–0.10) |

| Agatston score (Pixel × HU × 1000) | 136 ± 145 | 126 ± 118 | 0.78 (0.71–0.84) | 0.76 (0.69–0.82) |

| Calcification score (mm × HU × 1000) | 32 ± 28 | 19 ± 18 | 0.80 (0.73–0.85) | 0.63 (0.58–0.67) |

| Profoundly localized calcification (%) | 37 ± 39 | 29 ± 46 | 0.33 (0.18–0.46) | 0.32 (0.17–0.45) |

| Calcification spots <1 mm (n) | 6 ± 5 | 3 ± 2 | 0.30 (0.15–0.44) | 0.15 (0.07–0.21) |

| Parameter (Average ± SD) | Plaque | Patient | r a (CI b) | CCC c (CI) |

| Plaque volume (mm3) | 539 ± 154 | 551 ± 296 (CT d) | 0.59 (0.48–0.68) | 0.48 (0.39–0.56) |

| Average (GS e) | 61 ± 16 | 50 ± 27 | 0.33 (0.18–0.46) | 0.25 (0.14–0.36) |

| Median GSM (GS) | 40 ± 15.5 | 40 ± 30 | 0.19 (0.03–0.34) | 0.16 (0.03–0.28) |

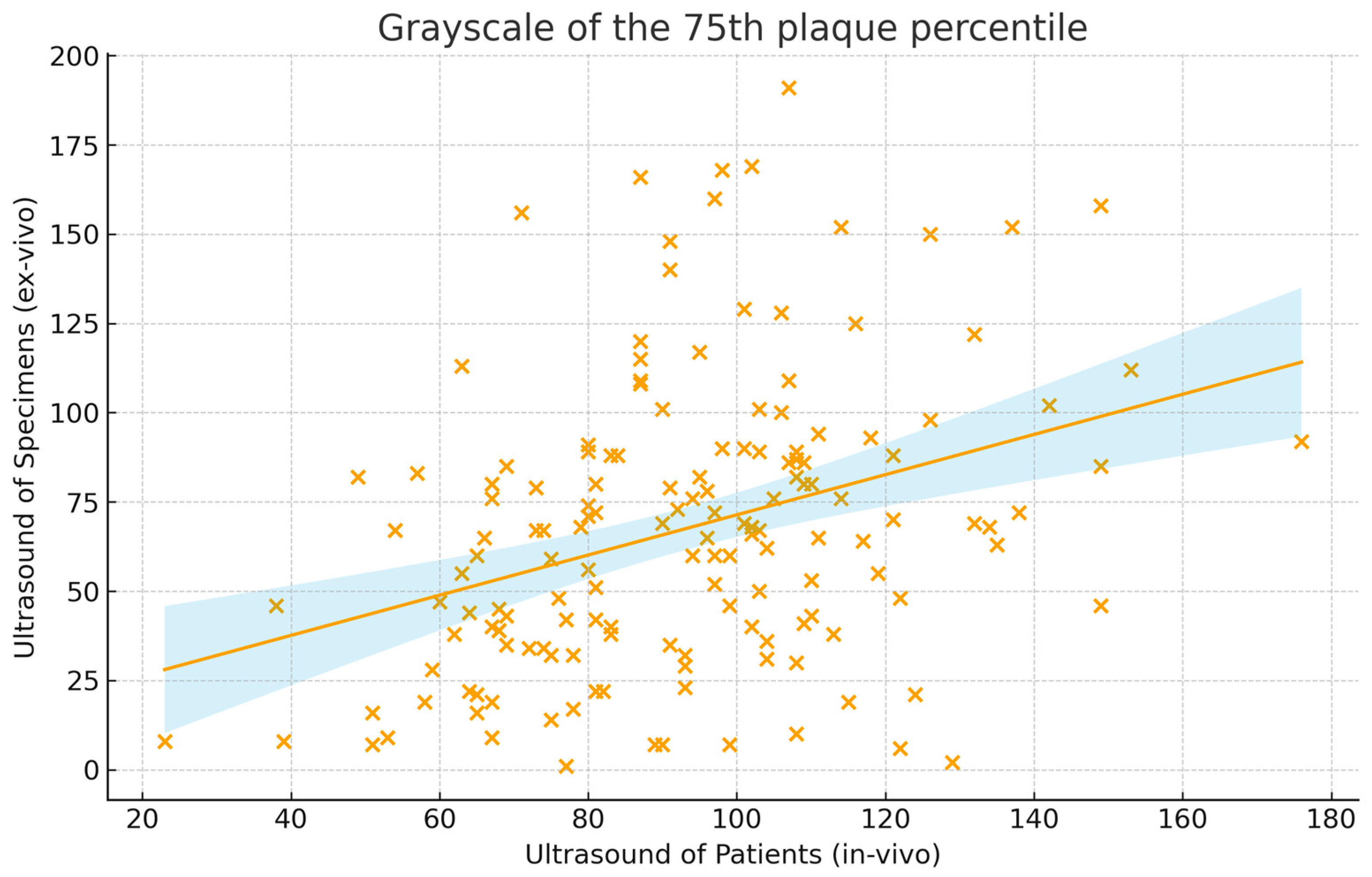

| GS of the 75th quantile (GS) | 92 ± 25 | 67 ± 38 | 0.35 (0.20–0.48) | 0.24 (0.14–0.34) |

| CV f | 0.65 ± 0.22 | 0.96 ± 0.50 | 0.20 (0.04–0.35) | 0.11 (0.02–0.19) |

| Proportion with GS < 25 (%) | 41 ± 8 | 42 ± 31 | 0.05 (−0.22–0.32) | 0.02 (−0.11–0.15) |

| Proportion with GS < 35 (%) | 49 ± 8 | 54 ± 47 | 0.05 (−0.22–0.32) | 0.02 (−0.07–0.11) |

| Binary Parameter (n (%)) | Plaque | Patient | Phi Correlation Coefficient (Φ) | |

| Echolucent | 31 (20) | 17 (11) | 0.14 (−0.03–0.32) | |

| More echolucent | 37 (24) | 29 (19) | 0.08 (−0.18–0.32) | |

| More echogenic | 54 (35) | 52 (33) | 0.15 (−0.01–0.31) | |

| Echogenic | 37 (24) | 59 (38) | 0.10 (−0.12–0.32) | |

| Juxtaluminal echolucency | 38 (24) | 16 (10) | 0.20 (0.04–0.35) | |

| DWA g | 94 (60) | 29 (19) | 0.17 (0.01–0.32) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stemmler, S.; Soschynski, M.; Czerny, M.; Zeller, T.; Westermann, D.; Macharzina, R.-R. Comparison of Carotid Plaque Ultrasound and Computed Tomography in Patients and Ex Vivo Specimens—Agreement of Composition Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020545

Stemmler S, Soschynski M, Czerny M, Zeller T, Westermann D, Macharzina R-R. Comparison of Carotid Plaque Ultrasound and Computed Tomography in Patients and Ex Vivo Specimens—Agreement of Composition Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):545. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020545

Chicago/Turabian StyleStemmler, Simon, Martin Soschynski, Martin Czerny, Thomas Zeller, Dirk Westermann, and Roland-Richard Macharzina. 2026. "Comparison of Carotid Plaque Ultrasound and Computed Tomography in Patients and Ex Vivo Specimens—Agreement of Composition Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020545

APA StyleStemmler, S., Soschynski, M., Czerny, M., Zeller, T., Westermann, D., & Macharzina, R.-R. (2026). Comparison of Carotid Plaque Ultrasound and Computed Tomography in Patients and Ex Vivo Specimens—Agreement of Composition Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020545