NT-proBNP as a Predictive and Prognostic Biomarker for Complications in Hypertensive Pregnancy Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

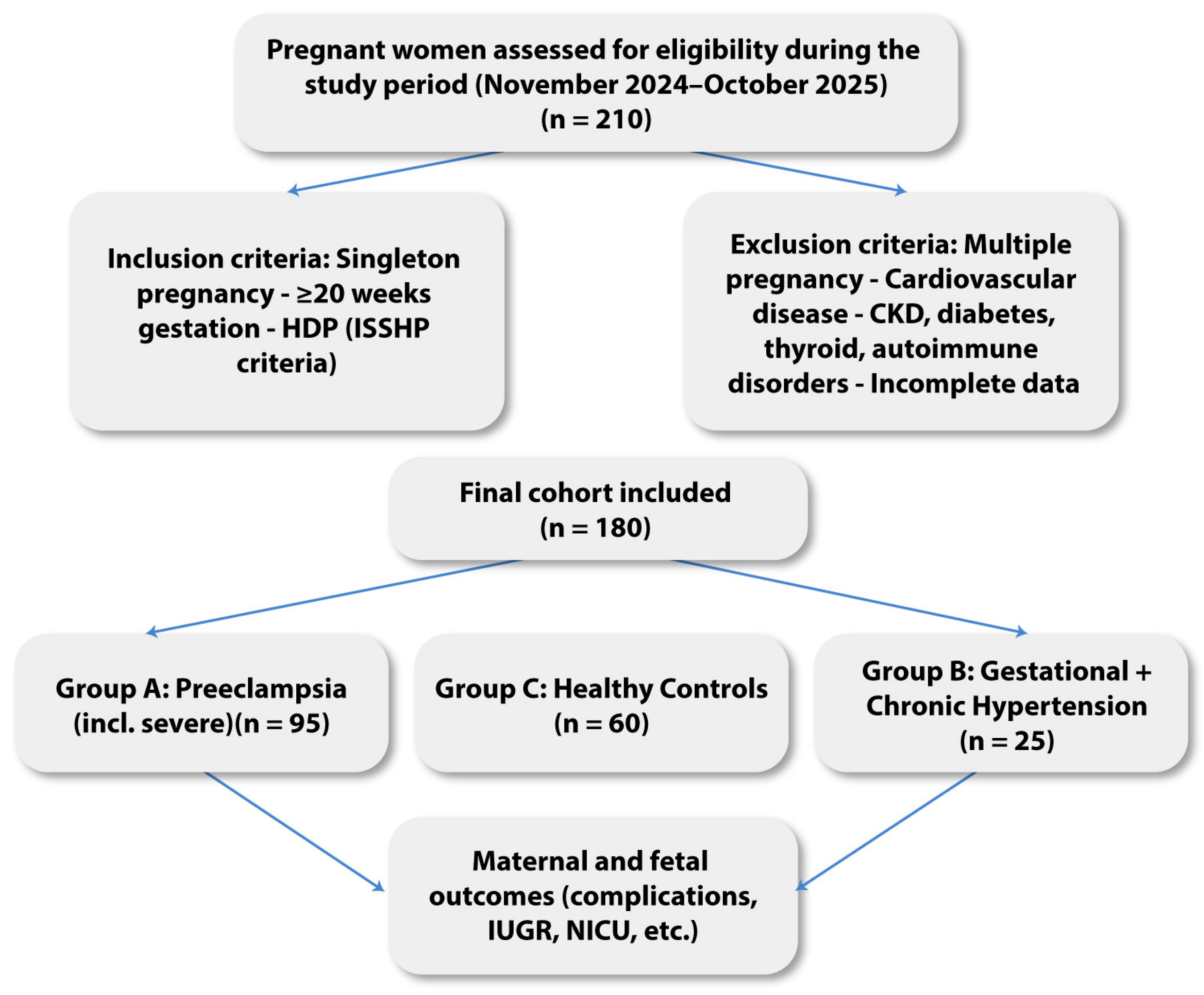

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Clinical and Laboratory Assessments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Relationship Between NT-proBNP Levels and HDP

3.3. NT-proBNP in Relation to Biological Indicators of Disease Severity

3.4. NT-proBNP Levels Across Hypertensive Disorder Subtypes

3.5. NT-proBNP Threshold for Prediction of Maternal–Fetal Complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Aziz, A.U.R.; Zhang, N. Trends in global and regional incidence and prevalence of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (1990–2021): An age–period–cohort analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Countouris, M.; Mahmoud, Z.; Cohen, J.B.; Crousillat, D.; Hameed, A.B.; Harrington, C.M.; Hauspurg, A.; Honigberg, M.C.; Lewey, J.; Lindley, K.; et al. Hypertension in Pregnancy and Postpartum: Current Standards and Opportunities to Improve Care. Circulation 2025, 151, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosół, N.; Procyk, G.; Kacperczyk-Bartnik, J.; Grabowski, M.; Gąsecka, A. N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide in gestational hypertension and PE—State of the art. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 297, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, A.S.; Rooney, M.R.; Fang, M.; Zhang, S.; Ndumele, C.E.; Tang, O.; Schulman, S.P.; Michos, E.D.; McEvoy, J.W.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.; et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Elevated NT-proBNP in Pregnant Women in the General U.S. Population. JACC Adv. 2023, 2, 100265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, N.; Gomez, J.; Rajapreyar, I.; Boelig, R.; Al-Kouatly, H. NT-proBNP in PE with severe features as a predictor of adverse maternal cardiac outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, S444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuermans, A.; Truong, B.; Ardissino, M.; Liu, Y.; Patel, R.S.; van Dijk, D.; Kim, J.; Hernandez, A.; Roberts, J.; O’Connor, C.; et al. Genetic associations of circulating cardiovascular proteins with gestational hypertension and PE. JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacmeister, L.; Buellesbach, A.; Glintborg, D.; Jorgensen, J.S.; Luef, B.M.; Birukov, A.; Heidenreich, A.; Lindner, D.; Keller, T.; Kraeker, K.; et al. Third-Trimester NT-proBNP for Pre-eclampsia Risk Prediction: A Comparison With sFlt-1/PlGF in a Population-Based Cohort. JACC Adv. 2025, 4, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockree, S.; Brook, J.; Shine, B.; James, T.; Vatish, M. Pregnancy-Specific Reference Intervals for BNP and NT-proBNP—Changes in Natriuretic Peptides Related to Pregnancy. J. Endocr. Soc. 2021, 5, bvab091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, A.A.; Scott, N.S. Dynamics of NT-proBNP in Pregnancy—Why Values May Be Elevated in the First Trimester. JACC Adv. 2023, 2, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suciu, V.-E.; Leucuța, D.-C.; Măluțan, A.M.; Iuhas, C.; Oancea, M.; Bucuri, C.E.; Roman, M.P.; Ormindean, C.; Mihu, D.; Ciortea, R. NT-proBNP and BNP as Biomarkers for Preeclampsia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Suzuki, L.; Takahashi, N.; Hanaue, M.; Soda, M.; Miki, T.; Tateyama, N.; Ishihara, S.; Koshiishi, T. Early-Pregnancy N-Terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide Level Is Inversely Associated with HDP Diagnosed after 35 Weeks of Gestation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucher, V.; Mitchell, A.R.; Gudmundsson, P.; Atkinson, J.; Wallin, N.; Asp, J.; Sennström, M.; Hildén, K.; Edvinsson, C.; Ek, J.; et al. Prediction of Adverse Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes Associated with Pre-Eclampsia and HDP: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 76, 102861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, M.N.; Garrido-Giménez, C.; García-Osuna, A.; García Manau, P.; Ullmo, J.; Mora, J.; Sánchez-García, O.; Platero, J.; Cruz-Lemini, M.; Llurba, E. N-Terminal Pro B-Type Natriuretic Peptide as Biomarker to Predict Pre-Eclampsia and Maternal–Fetal Complications. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 65, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speksnijder, L.; Rutten, J.H.W.; van den Meiracker, A.H.; de Bruin, R.J.A.; Lindemans, J.; Hop, W.C.J.; Visser, W. Amino-Terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP) Is a Biomarker of Cardiac Filling Pressures in Pre-Eclampsia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2010, 153, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauspurg, A.; Marsh, D.J.; McNeil, R.B.; Bairey Merz, C.N.; Greenland, P.; Straub, A.C.; Rouse, C.E.; Grobman, W.A.; Pemberton, V.L.; Silver, R.M.; et al. Association of N-Terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide Concentration in Early Pregnancy with Development of HDP and Future Hypertension. JAMA Cardiol. 2022, 7, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.X.; Nguyen, V.T.; Nguyen-Phan, H.N.; Hoang, B.B. Serum Levels of NT-ProBNP in Patients with PE. Integr. Blood Press. Control 2022, 15, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Giménez, C.; Cruz-Lemini, M.; Álvarez, F.V.; Nan, M.N.; Carretero, F.; Fernández-Oliva, A.; Mora, J.; Sánchez-García, O.; García-Osuna, Á.; Alijotas-Reig, J.; et al. Predictive Model for PE Combining sFlt-1, PlGF, NT-proBNP, and Uric Acid as Biomarkers. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabattini, E.; Tinè, G.; Caricati, A.; Viscioni, L.; Cerri, S.; Radaelli, T.; Barbieri, M.; Zamagni, G.; Stampalija, T.; Ferrazzi, E.; et al. Longitudinal Changes of Systemic Vascular Resistances in Pregnancies Complicated by Hypertensive Disorders and/or Fetal Growth Restriction. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 36, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, S.; Lemoine, E.; Granger, J.P.; Karumanchi, S.A. PE: Pathophysiology, Challenges, and Perspectives. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1094–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, U.D.; Olsson, M.G.; Kristensen, K.H.; Åkerström, B.; Hansson, S.R. Biomarkers in PE. Pregnancy Hypertens 2018, 13, 272–278. [Google Scholar]

- Stepan, H.; Galindo, A.; Hund, M.; Schlembach, D.; Sillman, J.; Surbek, D.; Vatish, M. Clinical Utility of sFlt-1 and PlGF in Screening, Prediction, Diagnosis and Monitoring of Pre-Eclampsia and Fetal Growth Restriction. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 61, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisler, H.; Llurba, E.; Chantraine, F.; Vatish, M.; Staff, A.C.; Sennström, M.; Olovsson, M.; Brennecke, S.P.; Stepan, H.; Allegranza, D.; et al. Predictive Value of the sFlt-1/PlGF Ratio in Women with Suspected PE. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchiorre, K.; Sharma, R.; Thilaganathan, B. Cardiovascular Implications in PE: An Overview. Circulation 2022, 146, 1690–1706. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkiewicz, J.; Darmochwał-Kolarz, D.A. Biomarkers for Early Prediction and Management of PE: A Comprehensive Review. Med. Sci. Monit. 2024, 30, e944104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiworapongsa, T.; Chaemsaithong, P.; Yeo, L.; Romero, R. Pre-Eclampsia Part 1: Current Understanding of Its Pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2014, 10, 466–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.Y.; Syngelaki, A.; Poon, L.C.; Rolnik, D.L.; O’Gorman, N.; Delgado, J.L.; Akolekar, R.; Konstantinidou, L.; Tsoumpou, I.; Wright, A.; et al. Screening for PE by Maternal Factors and Biomarkers at 11–13 Weeks’ Gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 52, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Group A: PE (n = 95) | Group B: GH + CH (n = 25) | Group C: Healthy Controls (n = 60) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years), mean ± SD | 31.8 ± 5.9 | 30.5 ± 5.4 | 28.7 ± 4.8 | 0.021 |

| Place of residence: Rural (%) | 55 (57.9%) | 16 (64.0%) | 24 (40.0%) | 0.038 |

| Place of residence: Urban (%) | 40 (42.1%) | 9 (36.0%) | 36 (60.0%) | 0.038 |

| Education: Primary/None (%) | 20 (21.1%) | 6 (24.0%) | 4 (6.7%) | 0.029 |

| Education: Secondary (%) | 18 (18.9%) | 5 (20.0%) | 10 (16.7%) | 0.029 |

| Education: High school (%) | 35 (36.8%) | 9 (36.0%) | 20 (33.3%) | 0.029 |

| Education: University (%) | 22 (23.2%) | 5 (20.0%) | 26 (43.3%) | 0.029 |

| Occupation: Employed (%) | 30 (31.6%) | 8 (32.0%) | 35 (58.3%) | 0.014 |

| Occupation: Unemployed/Jobless (%) | 65 (68.4%) | 17 (68.0%) | 25 (41.7%) | 0.014 |

| Complication | Group A: PE (n = 95) | Group B: GH + CH (n = 25) | Group C: Healthy Controls (n = 60) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal complications | ||||

| Severe hypertension (%) | 42 (44.2%) | 4 (16.0%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| HELLP syndrome (%) | 11 (11.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.014 |

| Acute kidney injury (%) | 7 (7.4%) | 1 (4.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.12 |

| Pulmonary edema (%) | 5 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.08 |

| Fetal complications | ||||

| Preterm birth < 37 w (%) | 38 (40.0%) | 5 (20.0%) | 2 (3.3%) | <0.001 |

| Fetal growth restriction (FGR) (%) | 26 (27.4%) | 3 (12.0%) | 1 (1.7%) | <0.001 |

| Low birth weight < 2500 g (%) | 24 (25.3%) | 3 (12.0%) | 1 (1.7%) | <0.001 |

| Group | N (%) | NT-proBNP, Median [IQR] (pg/mL) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A: PE | 95 (52.8%) | 210.0 [110.5–720.0] | <0.01 |

| Group B: GH + CH (without PE) | 25 (13.9%) | 120.5 [70.0–190.0] | 0.041 vs. A |

| Group C: Healthy Controls | 60 (33.3%) | 65.0 [40.0–110.0] | <0.001 vs. A |

| Marker | Correlation Coefficient (r) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Proteinuria | 0.45 | 0.002 |

| Uric acid | 0.38 | 0.008 |

| Creatinine | 0.41 | 0.004 |

| sFlt-1/PlGF ratio | 0.42 | <0.001 |

| Hypertensive Disorder Subtype | NT-proBNP, Median [IQR] (pg/mL) |

|---|---|

| Severe PE | 350.0 [200.0–820.0] |

| Moderate PE | 180.0 [95.0–420.0] |

| Gestational hypertension | 120.5 [70.0–190.0] |

| Chronic hypertension | 95.0 [60.0–150.0] |

| Healthy controls | 65.0 [40.0–110.0] |

| NT-proBNP Cut-Off (pg/mL) | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >100 | 0.66 (0.58–0.73) | 65.0 | 58.0 | 1.85 (0.92–3.74) | 0.081 |

| >150 | 0.72 (0.65–0.79) | 72.5 | 64.5 | 2.42 (1.15–5.12) | 0.045 |

| >200 | 0.78 (0.71–0.84) | 80.0 | 71.0 | 3.25 (1.42–7.45) | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mocuta, D.; Aur, C.; Zaha, I.A.; Cseppento, C.D.N.; Sachelarie, L.; Huniadi, A. NT-proBNP as a Predictive and Prognostic Biomarker for Complications in Hypertensive Pregnancy Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020519

Mocuta D, Aur C, Zaha IA, Cseppento CDN, Sachelarie L, Huniadi A. NT-proBNP as a Predictive and Prognostic Biomarker for Complications in Hypertensive Pregnancy Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):519. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020519

Chicago/Turabian StyleMocuta, Diana, Cristina Aur, Ioana Alexandra Zaha, Carmen Delia Nistor Cseppento, Liliana Sachelarie, and Anca Huniadi. 2026. "NT-proBNP as a Predictive and Prognostic Biomarker for Complications in Hypertensive Pregnancy Disorders" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020519

APA StyleMocuta, D., Aur, C., Zaha, I. A., Cseppento, C. D. N., Sachelarie, L., & Huniadi, A. (2026). NT-proBNP as a Predictive and Prognostic Biomarker for Complications in Hypertensive Pregnancy Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020519