Reference Diameters of the Abdominal Aorta and Iliac Arteries in Different Populations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Population Variability in Aorto-Iliac Arterial Diameters

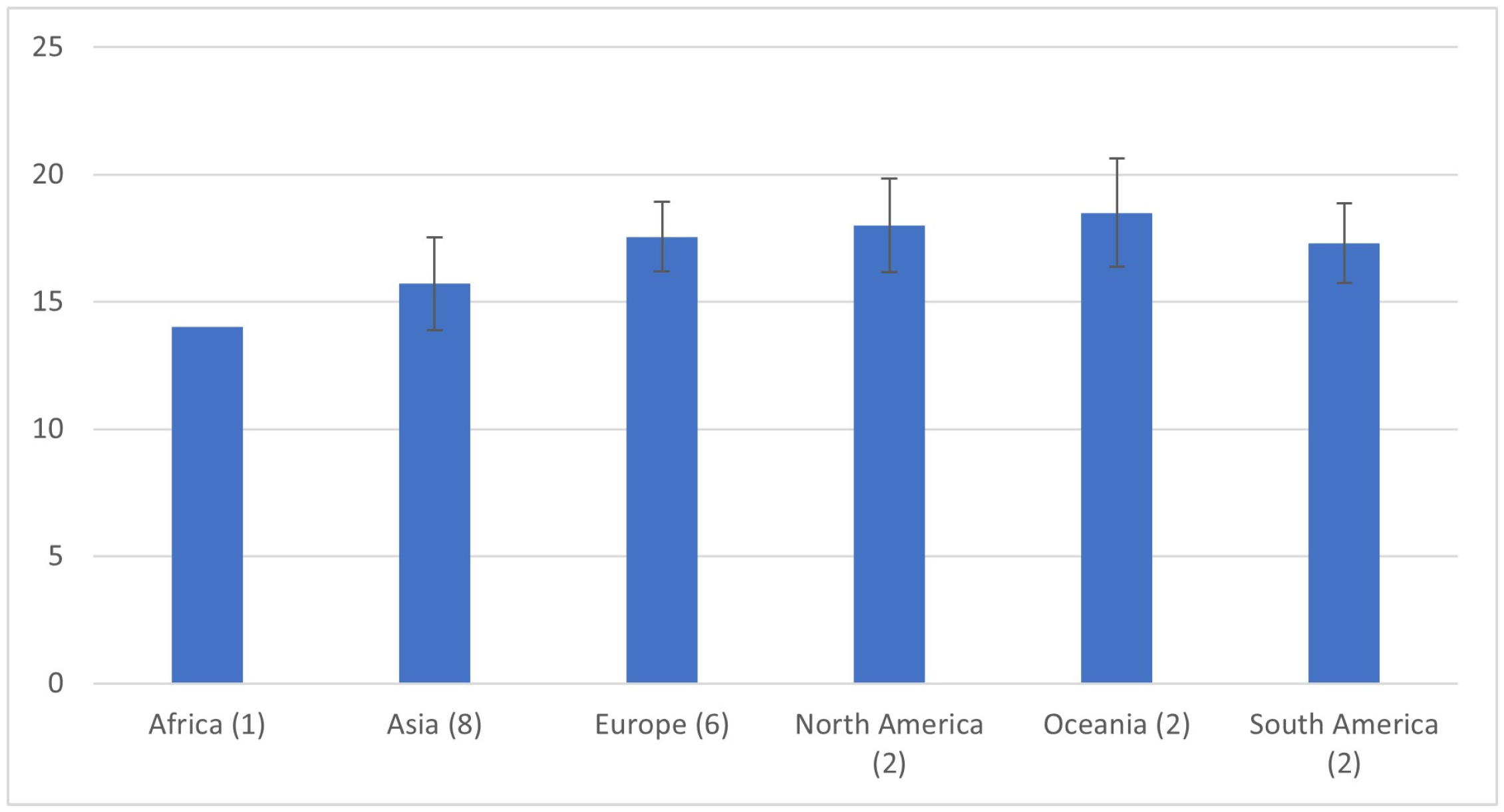

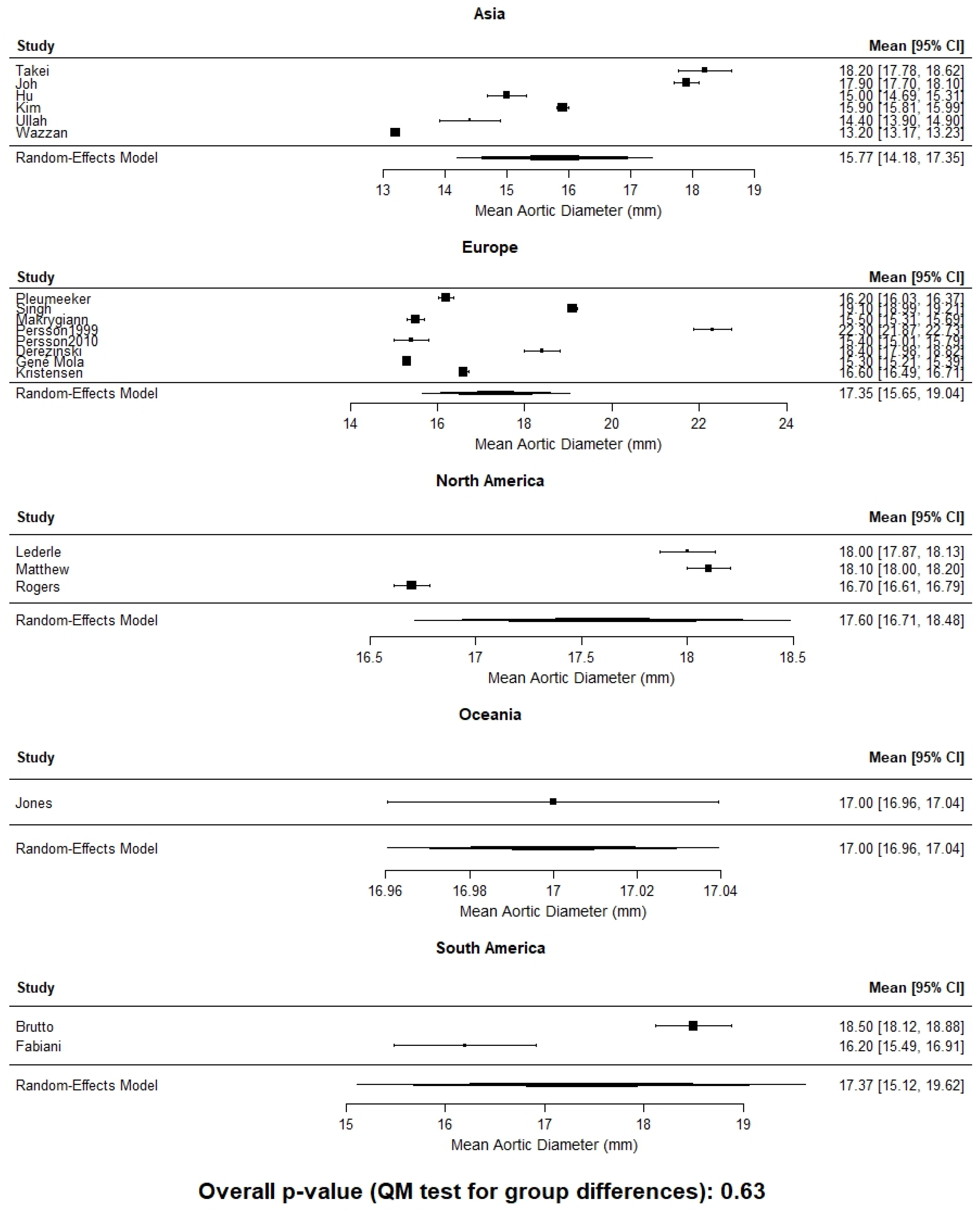

2.1. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Aortic Diameter

2.2. Updated Evidence

2.3. Iliac Artery Diameter Variability

3. Limitations of Fixed Diameter–Based Paradigms

4. Individualized Threshold Approaches

5. Clinical and Research Implications

6. Discussion

Limitations

7. Future Direction

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAA | Abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| ACC/AHA | American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association |

| ASI | Aortic size index |

| BSA | Body surface area |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| ESVS | European Society for Vascular Surgery |

| EVAR | Endovascular aneurysm repair |

| SVS | Society for Vascular Surgery |

| US | Ultrasound |

References

- Reimerink, J.J.; van der Laan, M.J.; Koelemay, M.J.; Balm, R.; Legemate, D.A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based mortality from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br. J. Surg. 2013, 100, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengtsson, H.; Bergqvist, D. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: A population-based study. J. Vasc. Surg. 1993, 18, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, K.C. Analysis of risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm in a cohort of more than 3 million individuals. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010, 52, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederle, F.A. Prevalence and associations of abdominal aortic aneurysm detected through screening. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997, 126, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, H.A.; Buxton, M.J.; Day, N.E.; Kim, L.G.; Marteau, T.M.; Scott, R.A.; Thompson, S.G.; Walker, N.M. The Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) into the effect of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening on mortality in men: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002, 360, 1531–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikof, E.L.; Dalman, R.L.; Eskandari, M.K.; Jackson, B.M.; Lee, W.A.; Mansour, M.A.; Mastracci, T.M.; Mell, M.; Murad, M.H.; Nguyen, L.L.; et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 67, 2–77.e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Mortality results for randomised controlled trial of early elective surgery or ultrasonographic surveillance for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. The UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Lancet 1998, 352, 1649–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederle, F.A.; Johnson, G.R.; Wilson, S.E.; Ballard, D.J.; Jordan, W.D., Jr.; Blebea, J.; Littooy, F.N.; Freischlag, J.A.; Bandyk, D.; Rapp, J.H.; et al. Rupture rate of large abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients refusing or unfit for elective repair. JAMA 2002, 287, 2968–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isselbacher, E.M.; Preventza, O.; Hamilton Black, J.; Augoustides, J.G.; Beck, A.W.; Bolen, M.A.; Braverman, A.C.; Bray, B.E.; Brown-Zimmerman, M.M.; Chen, E.P.; et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 146, e334–e482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanhainen, A.; Van Herzeele, I.; Bastos Goncalves, F.; Bellmunt Montoya, S.; Berard, X.; Boyle, J.R.; D’Oria, M.; Prendes, C.F.; Karkos, C.D.; Kazimierczak, A.; et al. Editor’s Choice—European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-Iliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2024, 67, 192–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joh, J.H.; Ahn, H.J.; Park, H.C. Reference diameters of the abdominal aorta and iliac arteries in the Korean population. Yonsei Med. J. 2013, 54, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Kwon, T.W.; Choi, E.; Jeong, S.; Kim, H.K.; Han, Y.; Cho, Y.P.; Yoon, H.K.; Choe, J.; Kim, W.H. Aortoiliac diameter and length in a healthy cohort. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabiani, M.A.; Gonzalez-Urquijo, M.; Silva-Platas, C.; Carrillo-Martínez, M.; Herrera-Vegas, D.; Morelli, L.; Vaquero-Puerta, C.; Montero-Baker, M.; Schönholz, C.; Hinojosa-González, D.; et al. Normal aortic diameters within the Mexican population and the impact of gender and ethnicity. Rev. Mex. Angiol. 2022, 50, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, G.A.; Allison, M.A.; Jensky, N.E.; Aboyans, V.; Wong, N.D.; Detrano, R.; Criqui, M.H. Abdominal aortic diameter and vascular atherosclerosis: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2011, 41, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subcommittee on Reporting Standards for Arterial Aneurysms; Ad Hoc Committee on Reporting Standards; Society for Vascular Surgery and North American Chapter; International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery; Johnston, K.W.; Rutherford, R.B.; Tilson, M.D.; Shah, D.M.; Hollier, L.; Stanley, J.C. Suggested standards for reporting on arterial aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 1991, 13, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, K.; Iwasawa, T.; Ono, T. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms during a basic medical checkup in residents of a Japanese rural community. Surg. Today 2000, 30, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zheng, Z.F.; Zhou, X.T.; Liu, Y.Z.; Sun, Z.M.; Zhen, Y.S.; Gao, B.L. Normal diameters of abdominal aorta and common iliac artery in middle-aged and elderly Chinese Han people based on CTA. Medicine 2022, 101, e30026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bild, D.E.; Detrano, R.; Peterson, D.; Guerci, A.; Liu, K.; Shahar, E.; Ouyang, P.; Jackson, S.; Saad, M.F. Ethnic Differences in Coronary Calcification. Circulation 2005, 111, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, I.S.; Massaro, J.M.; Truong, Q.A.; Mahabadi, A.A.; Kriegel, M.F.; Fox, C.S.; Thanassoulis, G.; Isselbacher, E.M.; Hoffmann, U.; O’Donnell, C.J. Distribution, determinants, and normal reference values of thoracic and abdominal aortic diameters by computed tomography (from the Framingham Heart Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 111, 1510–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Cho, S.; Sakalihasan, N.; Hultgren, R.; Joh, J.H. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Detected with Ultrasound in Korea and Belgium. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mola, A.G.; Díaz, C.T.; Martins, G.G.; Sari, X.T.; Montoya, S.B. Editor’s Choice—Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Normal Infrarenal Aortic Diameter in the General Worldwide Population and Changes in Recent Decades. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2022, 64, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dereziński, T.; Zozulińska-Ziółkiewicz, D.; Uruska, A.; Dąbrowski, M. Abdominal aorta diameter as a novel marker of diabetes incidence risk in elderly women. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezenwugo, U.M.; Okwudire, E.G.; Njeze, N.R.; Maduforo, C.O.; Moemenam, O.O. Abdominal aortic diameter and its determinants among healthy adults in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2020, 23, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.T.; Drinkwater, B.; Blake-Barlow, A.; Hill, G.B.; Williams, M.J.A.; Krysa, J.; van Rij, A.M.; Coffey, S. Both Small and Large Infrarenal Aortic Size is Associated with an Increased Prevalence of Ischaemic Heart Disease. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020, 60, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gené Mola, A.; Casasa, A.; Puig Reixach, T.; de La Figuera, M.; Jimenez, M.J.; Fité Matamoros, J.; Roman Escudero, J.; Bellmunt Montoya, S. Normal Infrarenal Aortic Diameter in Men and Women in a Mediterranean Area. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 92, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, J.S.S.; Obel, L.M.; Dahl, M.; Høgh, A.; Lindholt, J.S. Gender-specific Predicted Normal Aortic Size and Its Consequences of the Population-Based Prevalence of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 91, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanos, K.; Nana, P.; Roussas, N.; Batzalexis, K.; Karathanos, C.; Baros, C.; Giannoukas, A.D. Outcomes of a pilot abdominal aortic aneurysm screening program in a population of Central Greece. Int. Angiol. 2023, 42, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Imtiaz, N.; Ullah, S.; Fahad, M.S.; Nisar, U.; Ibrahim, N. Evaluation Of Normal Diameter Of Infra-Renal Aorta In A Pakistani Population Using Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2022, 34, 838–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazzan, M.; Abduljabbar, A.; Ajlan, A.; Ahmad, R.; Alhazmi, T.; Eskandar, A.; Khashoggi, K.; Alasadi, F.; Howladar, S.; Alshareef, Y. Reference for Normal Diameters of the Abdominal Aorta and Common Iliac Arteries in the Saudi Population. Cureus 2022, 14, e30695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, P.E.; Lawrence-Brown, M.; Semmens, J.; Mai, Q. The anatomical distribution of iliac aneurysms: Is there an embryological basis? Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2003, 25, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupski, W.C.; Selzman, C.H.; Floridia, R.; Strecker, P.K.; Nehler, M.R.; Whitehill, T.A. Contemporary management of isolated iliac aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 1998, 28, 1–11; discussion 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenberge, S.P.; Caputo, F.J.; Rowse, J.W.; Lyden, S.P.; Quatromoni, J.G.; Kirksey, L.; Smolock, C.J. Natural history and growth rates of isolated common iliac artery aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 76, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charisis, N.; Bouris, V.; Rakic, A.; Landau, D.; Labropoulos, N. A systematic review on endovascular repair of isolated common iliac artery aneurysms and suggestions regarding diameter thresholds for intervention. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 74, 1752–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeting, M.J.; Balm, R.; Desgranges, P.; Ulug, P.; Powell, J.T. Individual-patient meta-analysis of three randomized trials comparing endovascular versus open repair for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br. J. Surg. 2015, 102, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, B.T.; Terrin, M.C.; Dalman, R.L. Medical Management of Small Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Circulation 2008, 117, 1883–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obel Lasse, M.; Diederichsen Axel, C.; Steffensen Flemming, H.; Frost, L.; Lambrechtsen, J.; Busk, M.; Urbonaviciene, G.; Egstrup, K.; Karon, M.; Rasmussen Lars, M.; et al. Population-Based Risk Factors for Ascending, Arch, Descending, and Abdominal Aortic Dilations for 60–74–Year-Old Individuals. JACC 2021, 78, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olukorode, J.O.; Onwuzo, C.N.; Otabor, E.O.; Nwachukwu, N.O.; Omiko, R.; Omokore, O.; Kristilere, H.; Oladipupo, Y.; Akin-Adewale, R.; Kuku, O.; et al. Aortic Size Index Versus Aortic Diameter in the Prediction of Rupture in Women With Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Cureus 2024, 16, e58673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, R.C.; Lu, B.; Fokkema, M.T.; Conrad, M.; Patel, V.I.; Fillinger, M.; Matyal, R.; Schermerhorn, M.L. Relative importance of aneurysm diameter and body size for predicting abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture in men and women. J. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 59, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Nejim, B.; Faateh, M.; Mathlouthi, A.; Aurshina, A.; Malas, M.B. Association of abdominal aortic aneurysm diameter indexed to patient height with symptomatic presentation and mortality. J. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 75, 1606–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R.R.; Gallo, A.; Coady, M.A.; Tellides, G.; Botta, D.M.; Burke, B.; Coe, M.P.; Kopf, G.S.; Elefteriades, J.A. Novel Measurement of Relative Aortic Size Predicts Rupture of Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2006, 81, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyrønning, L.Å.; Skoog, P.; Videm, V.; Mattsson, E. Is the aortic size index relevant as a predictor of abdominal aortic aneurysm? A population-based prospective study: The Tromsø study. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2020, 54, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, T.P.; Moxon, J.V.; Gasser, T.C.; Golledge, J. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Peak Wall Stress and Peak Wall Rupture Index in Ruptured and Asymptomatic Intact Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e019772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, A.E.; Smith, T.A.; Ziganshin, B.A.; Elefteriades, J.A. The Mystery of the Z-Score. Aorta 2016, 4, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kimmenade, R.R.; Kempers, M.; de Boer, M.J.; Loeys, B.L.; Timmermans, J. A clinical appraisal of different Z-score equations for aortic root assessment in the diagnostic evaluation of Marfan syndrome. Genet. Med. 2013, 15, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak-Mielczarek, L.; Sabiniewicz, R.; Nowak, R.; Gilis-Malinowska, N.; Osowicka, M.; Mielczarek, M. New Screening Tool for Aortic Root Dilation in Children with Marfan Syndrome and Marfan-Like Disorders. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2020, 41, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ou, J.; Gong, W.; Wang, H.; Freebody, J. Morphologic Features of Symptomatic and Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm in Asian Patients. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 72, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golledge, J.; Velu, R.; Quigley, F.; Jenkins, J.; Singh, T.P. Editor’s Choice–Cohort Study Examining the Association Between Abdominal Aortic Size and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Aortic and Peripheral Occlusive and Aneurysmal Disease. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2021, 62, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederle Frank, A.; Wilson Samuel, E.; Johnson Gary, R.; Reinke Donovan, B.; Littooy Fred, N.; Acher Charles, W.; Ballard David, J.; Messina Louis, M.; Gordon Ian, L.; Chute Edmund, P.; et al. Immediate Repair Compared with Surveillance of Small Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1437–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; De Rango, P.; Verzini, F.; Parlani, G.; Romano, L.; Cieri, E. Comparison of surveillance versus aortic endografting for small aneurysm repair (CAESAR): Results from a randomised trial. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2011, 41, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouriel, K.; Clair, D.G.; Kent, K.C.; Zarins, C.K. Endovascular repair compared with surveillance for patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010, 51, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.L.; Smith, J.A.; Colvard, B.; Lee, J.T.; Stern, J.R. Precocious Rupture of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Below Size Criteria for Repair: Risk Factors and Outcomes. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 97, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartshorne, T.C.; McCollum, C.N.; Earnshaw, J.J.; Morris, J.; Nasim, A. Ultrasound Measurement of Aortic Diameter in a National Screening Programme. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2011, 42, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, U.K.; Norman, P.E.; Fowkes, F.G.; Aboyans, V.; Song, Y.; Harrell, F.E., Jr.; Forouzanfar, M.H.; Naghavi, M.; Denenberg, J.O.; McDermott, M.M.; et al. Estimation of global and regional incidence and prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysms 1990 to 2010. Glob. Heart 2014, 9, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Year | Country | Continent | Population | N | Age | Modality | AD (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derezinski (F) [22] | 2020 | Poland | Europe | Caucasian women, aged 65–74 | 200 | 69.5 | US | 18.4 ±3 |

| Ezenwugo [23] | 2020 | Nigeria | Africa | >18 years | 400 | NR | US | 14.0 ± 2 |

| Jones (M) [24] | 2020 | New Zealand | Oceania | >50 years (AAA screening program) | 1118 | 69.4 | US | 20.0 (18.3–22.0) |

| Jones (F) [24] | 2020 | New Zealand, | Oceania | >50 years (AAA screening program) | 1992 | 69.4 | US | 17.0 (15.4–18.8) |

| Gené Mola (M) [25] | 2023 | Spain | Europe | =65 years AAA screening program | 2089 | 65 | US | 17.9 ± 3.5 |

| Gené Mola (F) [25] | 2023 | Spain | Europe | >65 years AAA screening program | 2641 | 65 | US | 15.3 ± 2.3 |

| Kristensen (M) [26] | 2023 | Denmark | Europe | Viborg Vascular Screening Trial | 19,269 | 69.6 | US | 19.1 ± 5.3 |

| Kristensen (F) [26] | 2023 | Denmark | Europe | Viborg Vascular Screening Trial | 2426 | 67.1 | US | 16.6 ± 2.8 |

| Spanos (M) [27] | 2023 | Greece | Europe | Males > 60 years (AAA screening program) | 1187 | 71 | US | 18 ± 2 |

| Rogers (M) [19] | 2013 | USA | North America | Framingham Heart Study | 1767 | 49.8 | CT | 19.3 ± 2.9 |

| Rogers (F) [19] | 2013 | USA | North America | Framingham Heart Study | 1664 | 52.2 | CT | 16.7 ± 1.8 |

| Fabiani (M) [13] | 2022 | Mexico | South America | Retrospective study | 51 | 49.6 | CT | 18.4 ± 2.9 |

| Fabiani (F) [13] | 2022 | Mexico | South America | Retrospective study | 55 | 49.6 | CT | 16.2 ± 2.7 |

| Hu (M) [17] | 2022 | China | Asia | Retrospective study | 380 | 60 | CT | 17.9 ± 2.4 |

| Hu (F) [17] | 2022 | China | Asia | Retrospective study | 245 | 61 | CT | 15.0 ± 2.5 |

| Kim (M) [12] | 2022 | Korea | Asia | Retrospective study | 2379 | 56.8 | CT | 18.4 ± 1.8 |

| Kim (F) [12] | 2022 | Korea | Asia | Retrospective study | 1313 | 58.1 | CT | 15.9 ± 1.7 |

| Ullah (M) [28] | 2022 | Pakistan | Asia | Retrospective study | 194 | 39.5 | CT | 16.6 ± 2.2 |

| Ullah (F) [28] | 2022 | Pakistan | Asia | Retrospective study | 56 | 40.2 | CT | 14.4 ± 1.9 |

| Wazzan (M) [29] | 2022 | Saudi Arabia | Asia | Retrospective study | 160 | 50.8 | CT | 14.3 ± 0.2 |

| Author | Year | Country | Population | N | Modality | CIA Diameter (M, mm) | CIA Diameter (F, mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joh [11] | 2013 | Korea | Healthy adults | 1229 | US/CT | 11.9 ± 1.8 | 10.3 ± 1.5 |

| Kim [20] | 2022 | Korea | Healthy cohort | 3692 | CT | 12.4 ± 1.9 | 10.1 ± 1.6 |

| Hu [17] | 2022 | China | Middle-aged/elderly | 625 | CT | 11.2 ± 1.7 | 9.8 ± 1.5 |

| Rogers [19] | 2013 | USA | Framingham | 3431 | CT | 14.2 ± 2.1 | 12.7 ± 1.8 |

| Wazzan [29] | 2022 | Saudi Arabia | Healthy adults | 160 | CT | 12.3 ± 1.9 | 10.8 ± 1.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, H.; Cho, S.; Joh, J.H. Reference Diameters of the Abdominal Aorta and Iliac Arteries in Different Populations. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020518

Kim H, Cho S, Joh JH. Reference Diameters of the Abdominal Aorta and Iliac Arteries in Different Populations. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):518. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020518

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hyangkyoung, Sungsin Cho, and Jin Hyun Joh. 2026. "Reference Diameters of the Abdominal Aorta and Iliac Arteries in Different Populations" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020518

APA StyleKim, H., Cho, S., & Joh, J. H. (2026). Reference Diameters of the Abdominal Aorta and Iliac Arteries in Different Populations. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020518