The Diabetic Nose: A Narrative Review of Rhinologic Involvement in Diabetes (1973–2025)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Diabetes Mellitus Type 1

1.2. Diabetes Mellitus Type 2

1.3. An Overview of Nasal Disorders

1.3.1. Inflammatory and Infectious Disorders

1.3.2. Olfactory Dysfunction

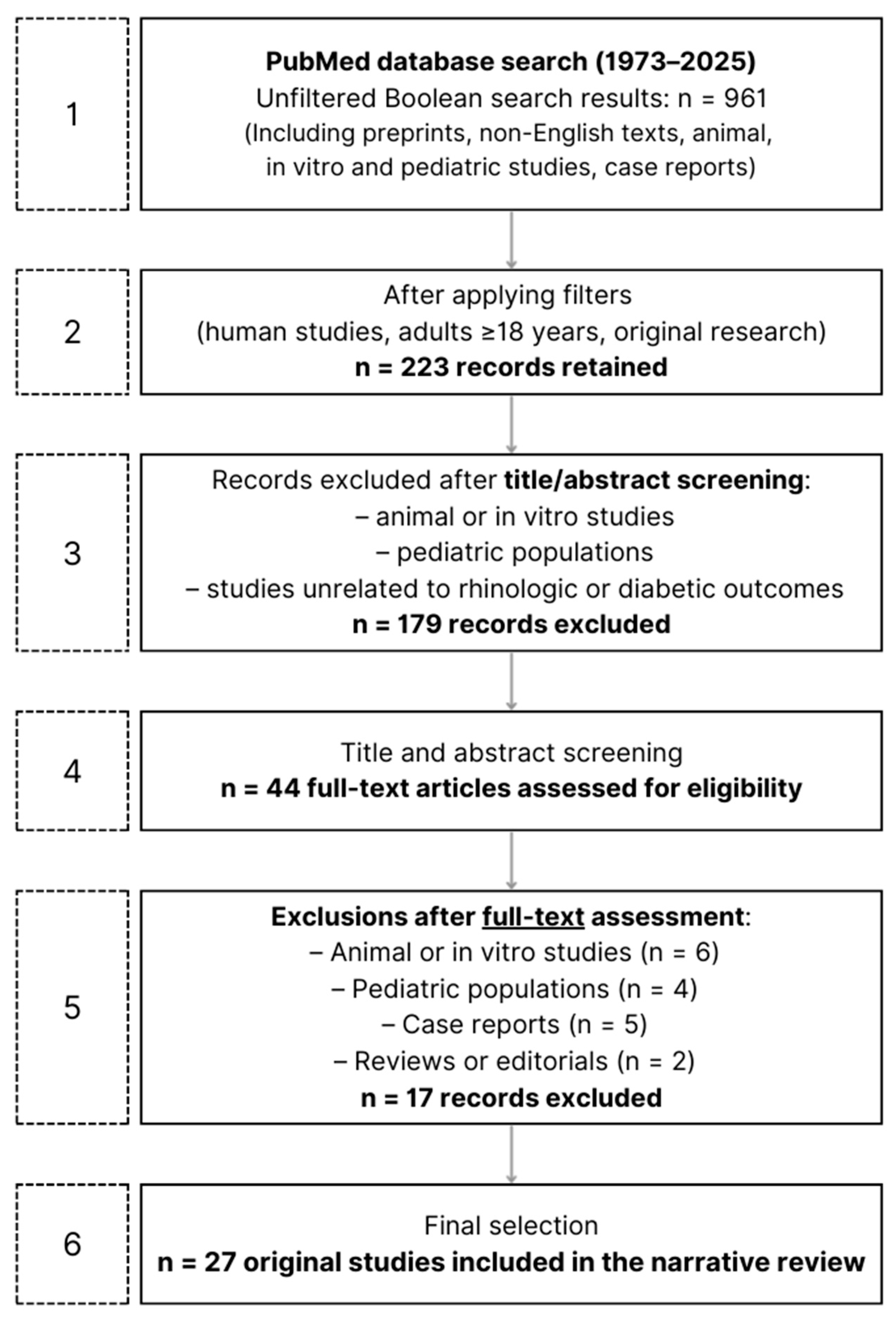

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research and Screening of the Literature

(“diabetes mellitus” OR “diabetes” OR “type 1 diabetes” OR “type 2 diabetes” OR “DM1” OR “DM2” OR “insulin-dependent diabetes” OR “non-insulin-dependent diabetes”)

AND

(“rhinitis” OR “allergic rhinitis” OR “non-allergic rhinitis” OR “vasomotor rhinitis” OR “atrophic rhinitis” OR “chronic rhinitis” OR “acute rhinitis” OR “infectious rhinitis” OR “sinusitis” OR “chronic sinusitis” OR “rhinorrhea” OR “nasal obstruction” OR “nasal congestion” OR “nasal discharge” OR “nasal dryness” OR “nasal crusting” OR “nasal polyps” OR “nasal inflammation” OR “nasal infection” OR “nasal mucosa” OR “nasal complications” OR “nose disease” OR “nose diseases” OR “sinonasal disease” OR “sinonasal inflammation” OR “olfactory dysfunction” OR “olfactory disorder” OR “olfactory impairment” OR “olfactory loss” OR “smell disorder” OR “smell loss” OR “anosmia” OR “hyposmia” OR “dysosmia” OR “parosmia” OR “phantosmia”)

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Review of the Literature

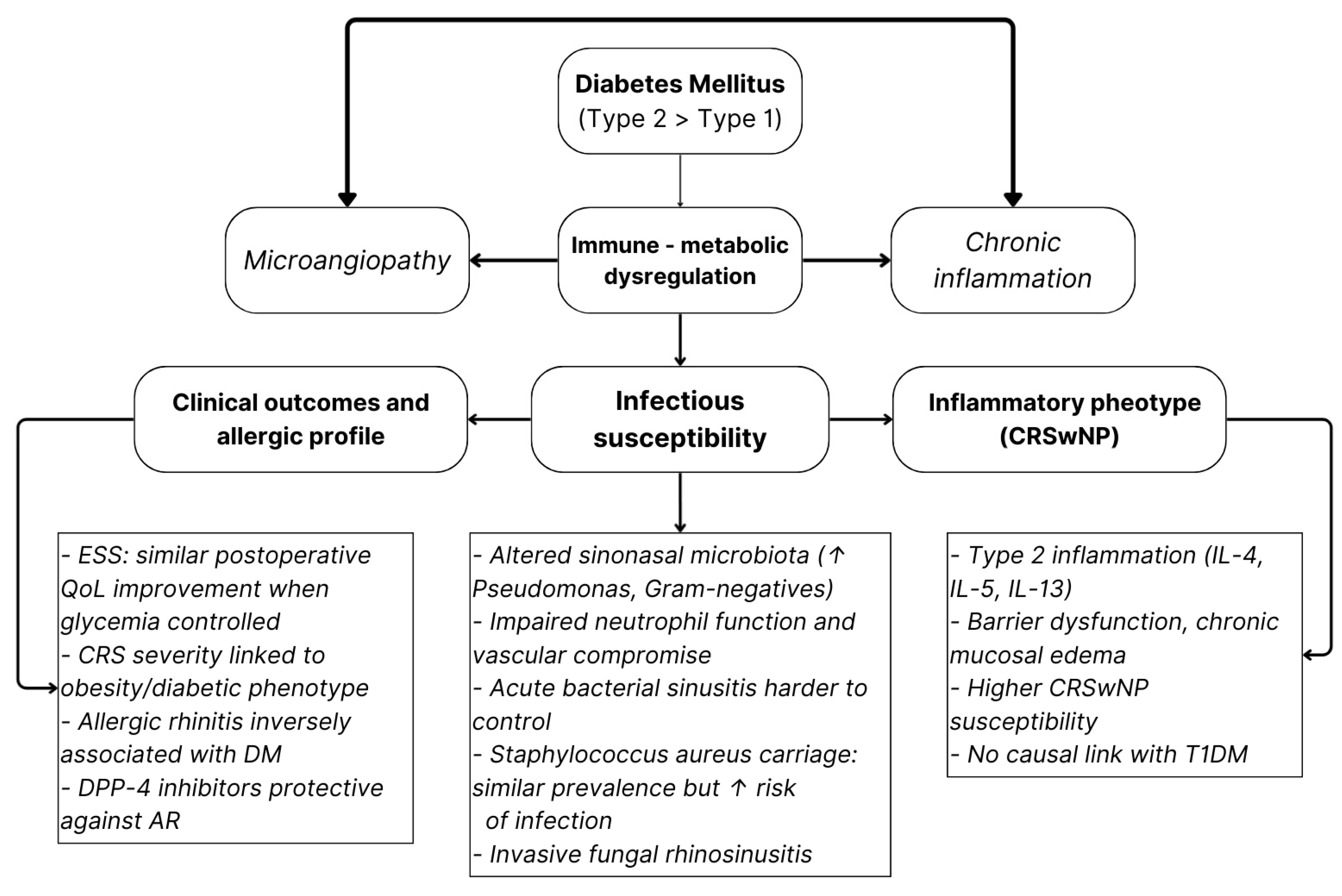

3.1. Inflammatory and Infectious Rhinologic Disorders

- CRSwNP susceptibility;

- Altered sinonasal microbiology with Gram-negative enrichment;

- Greater severity of bacterial or fungal infections.

3.2. Olfactory Disorders

3.3. Other Rhinologic Manifestations

3.4. Overall Conclusions and Implications

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Limitations of the Current Evidence

4.2. Variability in Diabetes Definition and Metabolic Characterization

4.3. Inconsistency in Rhinologic Outcome Assessment

4.4. Confounding Factors and Population Heterogeneity

4.5. Pathophysiological Framework and Interpretative Considerations

4.6. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

- Promote CRSwNP susceptibility and alter sinus microbiota toward Gram-negative enrichment;

- Accelerate olfactory decline via vascular and neuro-sensory compromise. Mirroring the established multidisciplinary pathways used to detect retinopathy in diabetes, olfactory testing might emerge as a similarly valuable tool, one that could be implemented early, perhaps even before symptom onset, to identify individuals at risk of neuro-sensory decline;

- Contribute to secondary rhinologic issues such as recurrent epistaxis, impaired mucociliary clearance, and increased infection severity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIFRS | Acute Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis |

| AFRS | Allergic Fungal Rhinosinusitis |

| AR | Allergic Rhinitis |

| ABS | Acute Bacterial Sinusitis |

| BOB | Blood–Olfactory Barrier |

| BSIT | Brief Smell Identification Test |

| CD26 | Cluster of Differentiation 26 |

| CGFRS | Chronic Granulomatous Fungal Rhinosinusitis |

| CIFRS | Chronic Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis |

| CRS | Chronic Rhinosinusitis |

| CRSsNP | Chronic Rhinosinusitis without Nasal Polyps |

| CRSwNP | Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps |

| DALYs | Disability-Adjusted Life Years |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| DPP-4 | Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 |

| ESS | Endoscopic Sinus Surgery |

| FESS | Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery |

| GWAS | Genome-Wide Association Study |

| HbA1c | Glycated Hemoglobin |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance |

| IDDM | Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ILC2 | Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells |

| KNHANES | Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| MRSA | Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| NHANES | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| NIDDM | Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus |

| OD | Olfactory Dysfunction |

| QOL/QoL | Quality of Life |

| S. aureus | Staphylococcus aureus |

| SIT-40 | Smell Identification Test–40 |

| SNOT-22 | Sino-Nasal Outcome Test–22 |

| T1D/T1DM | Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus |

| T2D/T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| Tfh | T Follicular Helper Cells |

| Th1/Th2/Th17 | T Helper Cells |

| Tregs | Regulatory T Cells |

References

- Bell, K.J.; Lain, S.J. The Changing Epidemiology of Type 1 Diabetes: A Global Perspective. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maahs, D.M.; West, N.A.; Lawrence, J.M.; Mayer-Davis, E.J. Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 39, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forlenza, G.P.; Rewers, M. The epidemic of type 1 diabetes: What is it telling us? Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2011, 18, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, T.; Sandholzer, H. The Epidemiology of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus; InTech: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, K.M. Type 1 diabetes: Pathogenesis and prevention. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. J. L’association Medicale Can. 2006, 175, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, S.; Deshmukh, A. Mapping of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2020, 16, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lernmark, A. Type 1 diabetes. Clin. Chem. 1999, 45, 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Stratigou, T.; Geladari, E.; Tessier, C.M.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Dalamaga, M. Diabetes type 1: Can it be treated as an autoimmune disorder? Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2021, 22, 859–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispham, J.A.; Hughes, A.S.; Driscoll, K.A.; McAuliffe-Fogarty, A.H. Novel Challenges in Aging with Type 1 Diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2020, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, N.; Matveyenko, A.V. Circadian Etiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Physiology 2018, 33, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, B.; Gulanick, M.; Lamendola, C. Risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2002, 16, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Shadangi, S.; Gupta, P.K.; Rana, S. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Comprehensive Review of Pathophysiology, Comorbidities, and Emerging Therapies. Compr. Physiol. 2025, 15, e70003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J. IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th edition scientific committee. In IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kautzky-Willer, A.; Harreiter, J.; Pacini, G. Sex and Gender Differences in Risk, Pathophysiology and Complications of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Endocr. Rev. 2016, 37, 278–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloyn, A.L.; Drucker, D.J. Precision medicine in the management of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, R.J.F.; Yeo, G.S.H. The genetics of obesity: From discovery to biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trang, K.; Grant, S.F.A. Genetics and epigenetics in the obesity phenotyping scenario. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2023, 24, 775–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunachie, S.; Chamnan, P. The double burden of diabetes and global infection in low and middle-income countries. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 113, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guber, C. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2005, 365, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillson, R. Treating people with type 2 diabetes. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2013, 74, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R. Type 2 diabetes: Etiology and reversibility. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, Z.A.; Walker, A.; Pirwani, M.M.; Tahiri, M.; Syed, I. Allergic rhinitis: Diagnosis and management. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2022, 83, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, E.J.; Overholser, A.; Schultz, P. Allergic Rhinitis. Prim. Care 2023, 50, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponda, P.; Carr, T.; Rank, M.A.; Bousquet, J. Nonallergic Rhinitis, Allergic Rhinitis, and Immunotherapy: Advances in the Last Decade. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.I.; Schwartz, G.; Bernstein, J.A. Allergic Rhinitis: Mechanisms and Treatment. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2016, 36, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lan, F.; Zhang, L. Update on pathomechanisms and treatments in allergic rhinitis. Allergy 2022, 77, 3309–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, S.; Irish, J.; Palumbo, S.; Lee, E.; Herbert, J.; Ramadan, I.; Chang, E.H. Viral infections and chronic rhinosinusitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 152, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.K.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Son, Y.; Park, J.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.; Smith, L.; Rahmati, M.; et al. Global Incidence and Prevalence of Chronic Rhinosinusitis: A Systematic Review. Clin. Exp. Allergy J. Br. Soc. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 55, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, M.S.; Moon, S.; Rha, M.S. Mucosal Inflammatory Memory in Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Cells 2024, 13, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalik, M.; Krawczyk, B. Chronic Rhinosinusitis-Microbiological Etiology, Potential Genetic Markers, and Diagnosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, T.M.; Altillo, B.S.A.; Milstone, A.M. Acute Bacterial Sinusitis: Limitations of Test-Based Treatment. JAMA 2023, 330, 326–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, J.; Lobo, D.; Anderson, S. Sinusitis. Prim. Care 2025, 52, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleckman, R.A. Acute bacterial sinusitis. Hosp. Pract. 1986, 21, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, R.M.; Piccirillo, J.F.; Chandrasekhar, S.S.; Brook, I.; Ashok Kumar, K.; Kramper, M.; Orlandi, R.R.; Palmer, J.N.; Patel, Z.M.; Peters, A.; et al. Clinical practice guideline (update): Adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. Off. J. Am. Acad. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 152, S1–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sande, M.A.; Gwaltney, J.M. Acute community-acquired bacterial sinusitis: Continuing challenges and current management. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2004, 39, S151–S158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldt, B.; Dion, G.R.; Weitzel, E.K.; McMains, K.C. Acute sinusitis. South. Med. J. 2013, 106, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montone, K.T. Pathology of Fungal Rhinosinusitis: A Review. Head Neck Pathol. 2016, 10, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, A.; Marple, B.F. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2004, 4, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, V.A.; Kern, R.C. Invasive fungal sinusitis and complications of rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 41, 497–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, T.; Whitcroft, K.L.; Andrews, P.; Altundag, A.; Cinghi, C.; Costanzo, R.M.; Damm, M.; Frasnelli, J.; Gudziol, H.; Gupta, N.; et al. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction. Rhinology. Suppl. 2017, 54, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, A.P. Olfactory dysfunction. Rhinology 1988, 26, 229–251. [Google Scholar]

- Wellford, S.A.; Moseman, E.A. Olfactory immunology: The missing piece in airway and CNS defence. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L. Olfactory dysfunction in chronic rhinosinusitis: Insights into the underlying mechanisms and treatments. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 19, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, T.M.; Murphy, C. Olfactory impairment. West. J. Med. 1993, 159, 71–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, J.S.; Roh, Y.H.; Kim, J.; Chang, S.W.; Ha, J.G.; Park, J.J.; Fahad, W.A.; Yoon, J.H.; Kim, C.H.; Cho, H.J. Association between diabetes mellitus and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps: A population-based cross-sectional study. Clin. Otolaryngol. Off. J. ENT-UK Off. J. Neth. Soc. Oto-Rhino Laryngol. Cervico Facial Surg. 2022, 47, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Adappa, N.D.; Lautenbach, E.; Chiu, A.G.; Doghramji, L.; Howland, T.J.; Cohen, N.A.; Palmer, J.N. The effect of diabetes mellitus on chronic rhinosinusitis and sinus surgery outcome. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014, 4, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjij, A.; Mace, J.C.; Soler, Z.M.; Smith, T.L.; Hwang, P.H. The impact of diabetes mellitus on outcomes of endoscopic sinus surgery: A nested case-control study. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015, 5, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, T.O.; Mace, J.C.; DeConde, A.S.; Xiao, C.C.; Storck, K.A.; Gudis, D.A.; Schlosser, R.J.; Soler, Z.M.; Smith, T.L. Does comorbid obesity impact quality of life outcomes in patients undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery? Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015, 5, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Meng, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, B.; Xie, S.; Zhong, W.; Jia, J.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, W.; Xie, Z. Hyperglycemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus associate with postoperative recurrence in chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Eur. Arch. Oto Rhino Laryngol. Off. J. Eur. Fed. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Soc. (EUFOS) Affil. Ger. Soc. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2025, 282, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.M.; Rice, D.H. Acute bacterial sinusitis and diabetes mellitus. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. Off. J. Am. Acad. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1987, 97, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; Hamilton, E.J.; Makepeace, A.; Davis, W.A.; Latkovic, E.; Lim, E.M.; Dyer, J.R.; Davis, T.M. Prevalence, risk factors and sequelae of Staphylococcus aureus carriage in diabetes: The Fremantle Diabetes Study Phase II. J. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2015, 29, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundarya, R.; Deepa, H.C.; Prakash, P.Y.; Geetha, V. Fungal Rhinosinusitis: An integrated diagnostic approach. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2025, 75, 152415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.K.; Jeon, Y.J.; Jung, S.J. Bi-directional association between allergic rhinitis and diabetes mellitus from the national representative data of South Korea. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, S.F.; Duffy, D.L.; Kyvik, K.O.; Skytthe, A.; Backer, V. Relationship between type 1 diabetes and atopic diseases in a twin population. Allergy 2011, 66, 645–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.H.; Li, S.Y.; Chen, W.; Kao, C.H. Association between Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors and Allergic Rhinitis in Asian Patients with Diabetes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Tan, L.; Qin, D.; Lv, H.; Liu, K.; Xu, Y.; Wu, X.; Huang, J.; Xu, Y. The causal relationship between multiple autoimmune diseases and nasal polyps. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1228226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, R.J.; Smith, T.L.; Mace, J.C.; Alt, J.; Beswick, D.M.; Mattos, J.L.; Payne, S.; Ramakrishnan, V.R.; Soler, Z.M. Factors driving olfactory loss in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: A case control study. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020, 10, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, D.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, B.G.; Kim, D.H.; Shin, J.H. The association between olfactory dysfunction and cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in middle-aged and older adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brämerson, A.; Johansson, L.; Ek, L.; Nordin, S.; Bende, M. Prevalence of olfactory dysfunction: The skövde population-based study. Laryngoscope 2004, 114, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekström, I.; Larsson, M.; Rizzuto, D.; Fastbom, J.; Bäckman, L.; Laukka, E.J. Predictors of Olfactory Decline in Aging: A Longitudinal Population-Based Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2020, 75, 2441–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstock, R.S.; Wright, H.N.; Smith, D.U. Olfactory dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Physiol. Behav. 1993, 53, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.Y.; Min, K.B. Insulin resistance and the increased risk for smell dysfunction in US adults. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, 1992–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.Y.K.; García-Esquinas, E.; Ko, O.H.; Tong, M.C.F.; Lin, S.Y. The Association Between Diabetes and Olfactory Function in Adults. Chem. Senses 2017, 43, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, Z.M.; Gregoski, M.J.; Kohli, P.; LaPointe, K.A.; Schlosser, R.J. Development and validation of the four-item Concise Aging adults Smell Test to screen for olfactory dysfunction in older adults. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2025, 15, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanke, H.; Mita, T.; Yoshii, H.; Yokota, A.; Yamashiro, K.; Ingaki, N.; Onuma, T.; Someya, Y.; Komiya, K.; Tamura, Y.; et al. Relationship between olfactory dysfunction and cognitive impairment in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 106, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkowski, B.; Chudziński, M.; Jakubowska, E.; Duda-Sobczak, A. Association of olfactory function with the intensity of self-reported physical activity in adults with type 1 diabetes. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2017, 127, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrich, V.; Brozek, A.; Boyle, T.R.; Chyou, P.H.; Yale, S.H. Risk factors for recurrent spontaneous epistaxis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 1636–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proença de Oliveira-Maul, J.; Barbosa de Carvalho, H.; Goto, D.M.; Maia, R.M.; Fló, C.; Barnabé, V.; Franco, D.R.; Benabou, S.; Perracini, M.R.; Jacob-Filho, W.; et al. Aging, diabetes, and hypertension are associated with decreased nasal mucociliary clearance. Chest 2013, 143, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.J.; Morice, A.H.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, S.E.; Jo, E.J.; Lee, S.M.; Han, J.W.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, S.H.; Jang, H.C.; et al. Cough in the elderly population: Relationships with multiple comorbidity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasia, D.; Owhonda, G.; Maduka, O.; Nwadiuto, I.; Arugu, G.; Tobin-West, C.; Azi, E.; Oris-Onyiri, V.; Urang, I.J.; Abikor, V.; et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 646 hospitalised SARS-Cov-2 positive patients in Rivers State Nigeria: A prospective observational study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 38, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaalan, M.; Abou Warda, A.E.; Osman, S.M.; Fathy, S.; Sarhan, R.M.; Boshra, M.S.; Sarhan, N.; Gaber, S.; Ali, A.M.A. The Impact of Sociodemographic, Nutritional, and Health Factors on the Incidence and Complications of COVID-19 in Egypt: A Cross-Sectional Study. Viruses 2022, 14, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivakumar, R.; White, J.; Villwock, J. Olfactory dysfunction in type II diabetes: Therapeutic options and lessons learned from other etiologies A scoping review. Prim. Care Diabetes 2022, 16, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaghloul, H.; Pallayova, M.; Al-Nuaimi, O.; Hovis, K.R.; Taheri, S. Association between diabetes mellitus and olfactory dysfunction: Current perspectives and future directions. Diabet. Med. A J. Br. Diabet. Assoc. 2018, 35, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.W.; Kim, D.Y.; Choi, S.; Won, S.; Kang, H.R.; Yi, H. Microbiome profiling of uncinate tissue and nasal polyps in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis using swab and tissue biopsy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toro-Ascuy, D.; Cárdenas, J.P.; Zorondo-Rodríguez, F.; González, D.; Silva-Moreno, E.; Puebla, C.; Nunez-Parra, A.; Reyes-Cerpa, S.; Fuenzalida, L.F. Microbiota Profile of the Nasal Cavity According to Lifestyles in Healthy Adults in Santiago, Chile. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Year | N. of Subjects | Results | Type of Diabetes | Association Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nam et al. [45] | 2022 | 34,670 (2608 with DM) | Significant association between DM and CRSwNP, but not with CRS without polyps. CRS patients with DM showed more nasal obstruction and olfactory dysfunction. | Clinically diagnosed DM (not specified) | Positive (for CRSwNP) |

| Lee et al. [53] | 2021 | 29,246 | Bidirectional inverse association between DM and allergic rhinitis: AR patients had lower odds of DM, and DM patients had lower odds of AR, consistent after adjustment. | Mainly T2DM (participants ≥ 30 years) | Negative |

| Chen et al. [55] | 2019 | 12,408 (6204 DPP-4 inhibitor users; 6204 controls) | DPP-4 inhibitor use in T2DM patients was associated with a lower incidence of allergic rhinitis (aHR = 0.81). High cumulative doses showed stronger protection. | T2DM | Negative (DPP-4 users less AR) |

| Hajjij et al. [47] | 2015 | 40 (20 DM; 20 controls) | DM did not affect postoperative outcomes of ESS in CRS patients. Both DM and controls had similar improvement in symptoms and QOL. | Mixed (insulin- and non-insulin-dependent) | Negative (no impact of DM on CRS outcomes) |

| Hart et al. [51] | 2015 | 660 | Nasal S. aureus carriage prevalence in diabetes similar to general population; however, carriers had a higher risk of subsequent S. aureus infection. | Mostly T2DM (97.1%) | Negative (no higher nasal carriage in DM) |

| Chen et al. [56] | 2023 | GWAS/UK Biobank data (exact N not stated) | Mendelian randomization showed no causal relationship between T1DM and nasal polyps in either sex. | T1DM | Negative |

| Soundarya et al. [52] | 2025 | 85 | Diabetes was the most common comorbidity, especially linked to invasive fungal rhinosinusitis (AIFRS, CIFRS). Diabetic patients had markedly higher risk and severity of invasive disease. | Not specified | Positive (for invasive FRS) |

| Jackson et al. [50] | 1987 | 15 | Diabetic patients with acute bacterial sinusitis had more severe and persistent infections, often requiring IV antibiotics and drainage; infections not more frequent but clinically more severe. | Adult-onset IDDM and NIDDM (T1DM and T2DM) | Positive (for severity of bacterial sinusitis) |

| Yuan et al. [49] | 2025 | 1163 CRS patients (134 with T2DM; 276 with post-operative recurrence) | T2DM was significantly more common in patients with postoperative recurrence; T2DM was an independent risk factor for recurrence. | T2DM | Positive |

| Zhang et al. [46] | 2014 | 376 (19 with DM) | DM associated with higher rates of P. aeruginosa and other Gram-negative bacteria in CRS, and poorer QOL improvement after FESS. | Predominantly T2DM (90%) | Positive (worse outcomes and altered microbiology in CRS) |

| Thomsen et al. [54] | 2011 | 54,530 twins (143 with T1DM) | No significant association between T1DM and hay fever or rhinoconjunctivitis in children or adults. | T1DM | Negative |

| Steele et al. [48] | 2015 | 241 | Diabetes more frequent among obese CRS patients. Both obesity and DM may contribute to chronic sinonasal inflammation; QOL improvement after ESS present but relatively reduced in obese/diabetic individuals. | Type 1 and 2 DM (comorbidity) | Positive (suggested contribution to CRS inflammation) |

| Reference | Year | N° of Subjects | Results | Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schlosser et al. [57] | 2020 | 388 (224 CRS; 164 controls) | Diabetes (type 1/type 2) independently associated with worse olfactory scores (lower TDI and identification); contributes to olfactory loss in CRS. | Positive |

| Roh et al. [58] | 2021 | 20,016 | Diabetes (both type 1 and type 2 not distinguished) associated with OD in unadjusted analysis, but not after multivariable adjustment. | Negative |

| Brämerson et al. [59] | 2004 | 1387 | Diabetes (type not specified; self-reported presence/absence) not linked to general OD, but significantly associated with anosmia (OR 2.6). | Positive (for anosmia only) |

| Ekström et al. [60] | 2020 | 1780 | Diabetes (type 1 and type 2 combined) predicted faster decline in odour identification over time, independent of other factors. | Positive |

| Weinstock et al. [61] | 1993 | 111 | Diabetic patients (both type 1 and type 2) showed reduced odour identification; impairment related to macrovascular disease, not glycaemic control. | Positive |

| Min et al. [62] | 2018 | 978 | Diabetes type 2/severe insulin resistance doubled the risk of smell dysfunction; no link with fasting glucose or HbA1c. | Positive |

| Chan et al. [63] | 2017 | 3151 | Insulin-treated diabetics had higher odds of phantosmia and severe OD; more intensive therapy correlated with worse smell function. Type 1 and type 2 DM not distinguished. | Positive |

| Soler et al. [64] | 2025 | 337 (190 development; 147 validation) | Type 2 DM was an independent predictor of OD in older adults (OR ≈ 3.7). | Positive |

| Sanke et al. [65] | 2014 | 250 | High prevalence of OD in elderly Type 2 DM; worse odour identification correlated with cognitive decline; no non-diabetic controls. | Positive (within diabetic cohort) |

| Falkowski et al. [66] | 2017 | 112 total | T1DM: higher prevalence of hyposmia compared with healthy controls (70% vs. 45.5%) | Positive |

| Study | Study Type | Population | Type of Diabetes | Investigated Rhinologic Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nam et al. (2022) [45] | Cross-sectional, population-based | 34,670 patients | Not specified (physician-diagnosed, treated with oral antidiabetic drugs or insulin) | CRSwNP, CRSsNP, OD |

| Lee et al. (2021) [53] | Nationwide cross-sectional, population-based | 29,246 adults (≥30 yrs) | Mainly T2DM (participants under 30 excluded) | AR, self-reported physician-diagnosed |

| Schlosser et al. (2020) [57] | Prospective, multi-institutional case-control | 388 (224 CRS; 164 controls) | T1DM and T2DM (self-reported, analysed together) | CRSwNP, CRSsNP; OD |

| Yuan et al. (2025) [49] | Retrospective cohort study | 1163 adult CRS patients undergoing surgery | T2DM | Postoperative recurrence of CRS |

| Roh et al. (2021) [58] | Population-based cross-sectional | 20,016 adults (≥40 yrs) | Not distinguished (self-reported, medication use, or fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL) | OD; rhinitis and rhinosinusitis as confounders |

| Chen et al. (2019) [55] | Retrospective cohort (propensity score–matched) | 12,408 (6204 DPP-4 users; 6204 controls) | T2DM | AR, ICD-9-coded physician diagnosis |

| Hajjij et al. (2015) [47] | Prospective nested case-control within multicenter cohort | 40 (20 DM; 20 matched controls) from a total cohort of 473 | Both insulin-dependent and non-insulin-dependent diabetes | CRS undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery |

| Hart et al. (2015) [51] | Community-based cross-sectional with prospective follow-up | 660 | Predominantly T2DM (97.1%) | Nasal Staphylococcus aureus colonization (including MRSA) |

| Ekström et al. (2020) [60] | Prospective longitudinal population-based cohort | 1780 (dementia-free adults with ≥2 follow-ups over 12 years) | Mainly T2DM (7.6% prevalence) | OD (odour identification decline, Sniffin’ Sticks test) |

| Chen et al. (2023) [56] | Two-sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization | Large GWAS and UK Biobank datasets (European ancestry; sex-stratified) | T1DM | CRSwNP |

| Chan et al. (2017) [63] | Cross-sectional, population-based (NHANES 2013–2014) | 3151 adults (≥40 yrs, multiethnic) | Predominantly T2DM (biochemical or physician-diagnosed) | OD (hyposmia, anosmia, phantosmia; 8-item smell test and self-report) |

| Soundarya et al. (2025) [52] | Retrospective observational (tertiary hospital) | 85 patients with fungal rhinosinusitis (FRS) | Not specified (likely Type 2; 95% of AIFRS cases diabetic) | Fungal rhinosinusitis (invasive and non-invasive forms: AIFRS, CIFRS, CGFRS, AFRS, fungal ball) |

| Weinstock et al. (1993) [61] | Cross-sectional observational | 111 diabetic patients (VA and SUNY centers, USA) | Both T1DM (27%) and T2DM (73%) | OD (odour identification impairment, OCM test) |

| Jackson & Rice (1987) [50] | Retrospective case series | 15 diabetic patients (26–71 yrs; 10 IDDM, 5 NIDDM) | Both T1DM (insulin-dependent) and T2DM (non-insulin-dependent) | Acute bacterial sinusitis (mostly maxillary; culture-proven) |

| Zhang et al. (2014) [46] | Retrospective cohort | 376 CRS patients (19 with DM; mean age 48 ± 13 yrs) | Both T1DM (10%) and T2DM (90%) | CRS undergoing ESS; bacterial culture and QOL outcomes |

| Song et al. (2013) [69] | Cross-sectional, community-based elderly cohort | 796 adults (≥65 yrs) | Predominantly T2DM (HbA1c-based definition; uncontrolled ≥8%) | Cough phenotypes (frequent, persistent, nocturnal); AR as comorbidity/confounder |

| Thomsen et al. (2011) [54] | Nationwide twin registry cross-sectional study | 54,530 Danish twins (ages 3–71; 143 with T1DM) | T1DM | Hay fever and rhinoconjunctivitis (questionnaire-based diagnosis) |

| Schaalan et al. (2022) [71] | Cross-sectional population-based survey | 15,166 Egyptian adults (18–71 yrs) | Not specified (10.9% diabetic) | Anosmia and ageusia during COVID-19 infection |

| Min & Min (2018) [62] | Cross-sectional, population-based (NHANES 2013–2014) | 978 adults (≥50 yrs) | T2DM (self-reported or glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL); insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) | OD (8-item identification test; score ≤ 5 = dysfunction) |

| Proença de Oliveira-Maul et al. (2013) [68] | Cross-sectional observational | 252 (79 healthy; 173 with DM and/or HTN) | Both T1DM and T2DM | Decreased nasal mucociliary clearance (saccharin transit test >12 min) |

| Sanke et al. (2014) [65] | Cross-sectional | 250 elderly Japanese patients with T2DM (≥65 yrs; median 72) | T2DM | OD (odour identification via Open Essence test) |

| Abrich et al. (2014) [67] | Retrospective cohort | 1373 total (461 recurrent epistaxis; 912 controls) | Both T1DM and T2DM | Recurrent spontaneous epistaxis |

| Falkowski et al. (2017) [66] | Cross-sectional observational | 112 total (90 T1DM; 22 healthy controls) | T1DM | OD (Sniffin’ Sticks identification test) |

| Steele et al. (2015) [48] | Prospective, multi-institutional observational cohort | 241 adults with CRS (66 normal, 76 overweight, 99 obese) | Both T1DM and T2DM (3–11% prevalence depending on BMI) | CRS undergoing ESS; analysis of QOL outcomes by BMI/DM status |

| Brämerson et al. (2004) [59] | Cross-sectional, population-based (Skövde Study, Sweden) | 1387 adults (aged ≥20 yrs) | DM (type not specified; self-reported) | OD (hyposmia, anosmia) |

| Alasia et al. (2021) [70] | Prospective, multicentre observational (COVID-19 cohort) | 646 hospitalized SARS-CoV-2 positive patients | DM (7.7% diabetic) | Anosmia (12.7%) and rhinorrhoea (3.3%) reported as rhinologic symptoms |

| Soler et al. (2025) [64] | Prospective cross-sectional (development + validation cohorts) | 357 total (20 focus group, 190 development, 147 validation) | T2DM non-insulin-dependent | OD (Sniffin’ Sticks and SIT-40 tests) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Passali, G.C.; Santantonio, M.; Passali, D.; Passali, F.M. The Diabetic Nose: A Narrative Review of Rhinologic Involvement in Diabetes (1973–2025). J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020472

Passali GC, Santantonio M, Passali D, Passali FM. The Diabetic Nose: A Narrative Review of Rhinologic Involvement in Diabetes (1973–2025). Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):472. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020472

Chicago/Turabian StylePassali, Giulio Cesare, Mariaconsiglia Santantonio, Desiderio Passali, and Francesco Maria Passali. 2026. "The Diabetic Nose: A Narrative Review of Rhinologic Involvement in Diabetes (1973–2025)" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020472

APA StylePassali, G. C., Santantonio, M., Passali, D., & Passali, F. M. (2026). The Diabetic Nose: A Narrative Review of Rhinologic Involvement in Diabetes (1973–2025). Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020472