Could Lipo-Prostaglandin E1 Be the Key to Improving Success Rates in Free-Flap Microsurgery? A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

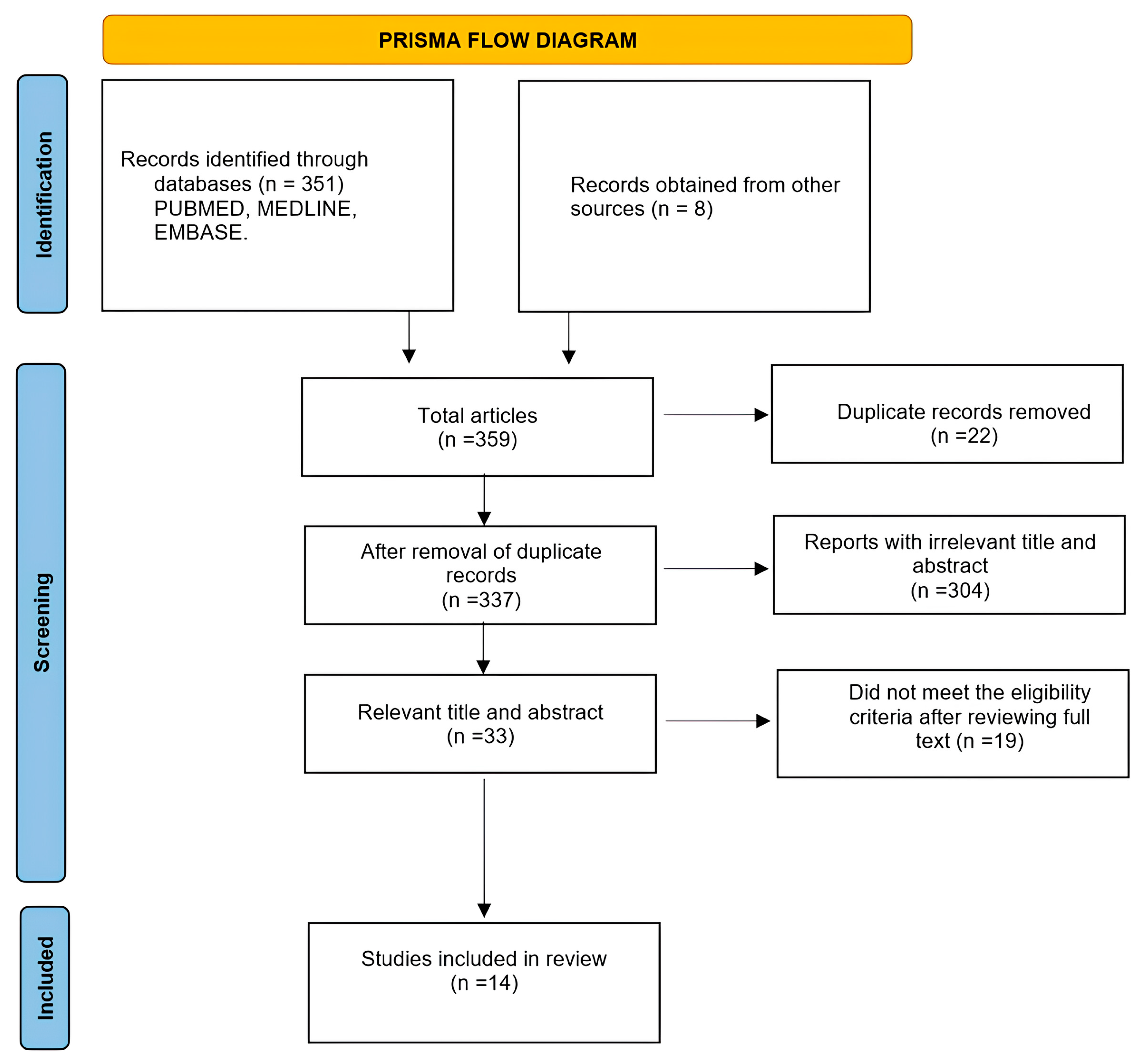

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Endpoints

2.4. Data Abstraction, Study Selection, and Quality Process

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.3. Types of Surgery

3.4. Medications

3.5. Uses

3.6. Effectiveness and Complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PGE1 | Prostaglandin E1 |

References

- McLean, D.H.; Buncke, H.J., Jr. Autotransplant of omentum to a large scalp defect, with microsurgical revascularization. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1972, 49, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouri, R.K.; Cooley, B.C.; Kunselman, A.R.; Landis, J.R.; Yeramian, P.; Ingram, D.; Natarajan, N.; Benes, C.O.; Wallemark, C. A prospective study of microvascular free-flap surgery and outcome. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1998, 102, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakovic, D.; Patel, R.S.; Goldstein, D.P.; Gullane, P.J. Salvage of failed free flaps used in head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck Oncol. 2009, 1, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigley, F.M.; Flavahan, N.A. Raynaud’s phenomenon. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzer, K.; Rogatti, W.; Rüttgerodt, K. Efficacy and tolerability of intra-arterial and intravenous prostaglandin E1 infusions in occlusive arterial disease stage III/IV. Vasa Suppl. 1989, 28, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kröger, K.; Hwang, I.; Rudofsky, G. Recanalization of chronic peripheral arterial occlusions by alternating intra-arterial rt-PA and PGE1. Vasa 1998, 27, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murota, H.; Kotobuki, Y.; Umegaki, N.; Tani, M.; Katayama, I. New aspect of anti-inflammatory action of lipo-prostaglandinE1 in the management of collagen diseases-related skin ulcer. Rheumatol. Int. 2008, 28, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, Y.; Shiokawa, Y.; Homma, M.; Kashiwazaki, S.; Ichikawa, Y.; Hashimoto, H.; Sakuma, A. A multicenter double blind controlled study of lipo-PGE1, PGE1 incorporated in lipid microspheres, in peripheral vascular disease secondary to connective tissue disorders. J. Rheumatol. 1987, 14, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Okuda, Y.; Mizutani, M.; Ogawa, M.; Sone, H.; Asano, M.; Tsurushima, Y.; Morishima, Y.; Asakura, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Isaka, M. Hemodynamic effects of lipo-PGE1 on peripheral artery in patients with diabetic neuropathy: Evaluated by two-dimensional color Doppler echography. Diabetes Res. 1993, 22, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Miyata, T.; Yamada, N.; Miyachi, Y. Efficacy by ulcer type and safety of lipo-PGE1 for Japanese patients with diabetic foot ulcers. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2010, 17, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Wu, F.; Li, P.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Cui, W.; Ding, Y.; An, Q.; et al. Therapeutic effect of liposomal prostaglandin E1 in acute lower limb ischemia as an adjuvant to hybrid procedures. Exp. Ther. Med. 2013, 5, 1760–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Vegas, J.M.; Ruiz Alonso, M.E.; Terán Saavedra, P.P. PGE-1 in replantation and free tissue transfer: Early preliminary experience. Microsurgery 2007, 27, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, S.; Kawabata, K.; Mitani, H. Analysis of 59 cases with free flap thrombosis after reconstructive surgery for head and neck cancer. Auris Nasus Larynx 2010, 37, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.P.; Koshima, I. Using perforators as recipient vessels (supermicrosurgery) for free flap reconstruction of the knee region. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2010, 64, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitate, E.; Sasaguri, M.; Oobu, K.; Mitsuyasu, T.; Tanaka, A.; Kiyosue, T.; Nakamura, S. Postoperative changes of blood flow in free microvascular flaps transferred for reconstruction of oral cavity: Effects of intravenous infusion of prostaglandin E1. Asian J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 23, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, T.L.H.; Park, S.W.; Cho, J.Y.; Choi, J.W.; Hong, J.P. The search for the ideal thin skin flap: Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap—A review of 210 cases. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 135, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; Sawaizumi, M.; Imai, T.; Matsumoto, S. Continuous local intraarterial infusion of anticoagulants for microvascular free tissue transfer in primary reconstruction of the lower limb following resection of sarcoma. Microsurgery 2010, 30, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, H.S.; Gokavarapu, S.; Al-Qamachi, L.; Yin, M.Y.; Su, L.X.; Ji, T.; Zhang, C.P. Justification of routine venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in head and neck cancer reconstructive surgery. Head Neck 2017, 39, 2450–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuiwa, T.; Nishimoto, K.; Hayashi, T.; Kurono, Y. Venous thrombosis after microvascular free-tissue transfer in head and neck cancer reconstruction. Auris Nasus Larynx 2008, 35, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.M.G.; Chen, Y.C.; Tan, N.C.; Lin, P.Y.; Tsai, Y.T.; Chang, H.W.; Kuo, Y.R. The outcome of prostaglandin-E1 and dextran-40 compared to no antithrombotic therapy in head and neck free tissue transfer: Analysis of 1,351 cases in a single center. Microsurgery 2012, 32, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.Y.; Cabrera, R.; Chew, K.Y.; Kuo, Y.R. The outcome of free tissue transfers in patients with hematological diseases: 20-year experiences in single microsurgical center. Microsurgery 2014, 34, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.J.; Suh, H.P.; Lee, J.; Hwang, J.H.; Hong, J.P.J.; Kim, Y.K. Lipo-Prostaglandin E1 increases immediate arterial maximal flow velocity of free flap in patients undergoing reconstructive surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2019, 63, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.Y.; Lin, Y.S.; Chen, L.W.; Yang, K.C.; Huang, W.C.; Liu, W.C. Risk of free flap failure in head and neck reconstruction: Analysis of 21,548 cases from a nationwide database. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2020, 84, S3–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Jin, S.J.; Suh, H.P.; Lee, S.A.; Cho, C.; Yu, J.; Hwang, J.H.; Hong, J.P.; Kim, Y.K. The role of age in determining the effects of lipo-PGE1 infusion on immediate arterial maximal flow velocity in patients with diabetes undergoing free flap surgery for lower extremity reconstruction: A prospective observational study. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2020, 73, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Lee, S.; Eun, S. A novel reconstruction approach after skin cancer ablation using lateral arm free flap: A serial case report. Medicina 2024, 60, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Lee, K.T. Clinical effectiveness of postoperative prostaglandin E1 administration in reducing flap necrosis following microsurgical reconstruction. Microsurgery 2024, 44, e31166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanasono, M.M.; Butler, C.E. Prevention and treatment of thrombosis in microvascular surgery. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2008, 24, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askari, M.; Fisher, C.; Weniger, F.G.; Bidic, S.; Lee, W.P.A. Anticoagulation therapy in microsurgery: A review. J. Hand. Surg. Am. 2006, 31, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouri, R.K.; Cooley, B.C.; Kenna, D.M.; Edstrom, L.E. Thrombosis of microvascular anastomoses in traumatized vessels: Fibrin versus platelets. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1990, 86, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cooley, B.C. Effect of anticoagulation and inhibition of platelet aggregation on arterial vs venous microvascular thrombosis. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1995, 35, 169–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieslander, J.B.; Dougan, P.; Stjernquist, U.; Aberg, M.; Bergentz, S.E. The influence of dextran and saline solution upon platelet behavior after microarterial anastomoses. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1986, 163, 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, C.R.; Iorio, M.L.; Lee, B.T. A systematic review of topical vasodilators for the treatment of intraoperative vasospasm in reconstructive microsurgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 136, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, A.Y.; Lonie, S.; Lim, K.; Farthing, H.; Hunter-Smith, D.J.; Rozen, W.M. Free flap monitoring, salvage, and failure timing: A systematic review. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2021, 37, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; He, J.F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.M. Intraoperative factors associated with free flap failure in the head and neck region: A four-year retrospective study of 216 patients and review of the literature. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 48, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, P.L.; Boriani, F.; Khan, U.; Atzeni, M.; Figus, A. Rate of free flap failure and return to the operating room in lower limb reconstruction: A systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocini, R.; Muneretto, C.; Lobbia, G.; Zatta, E.; Athena Eliana, A.; Molteni, G.; Arietti, V.; Barbera, G. Management of the Venous Anastomoses of a Tertiary Referral Centre in Reconstructive Microvascular Surgery Using Fasciocutaneous Free Flaps in the Head and Neck. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Type of Study | Surgery | Limitations of the Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rodríguez Vegas, Ruiz Alonso & Terán Saavedra (2007) [12] | retrospective | 16 micro-replantations 46 free flaps (different locations) | No control group + other medications |

| Fukuiwa 2008 [19] | retrospective | 102 free flaps (head and neck) | No control group |

| Yoshimoto 2010 [13] | retrospective | 1031 free flaps (head and neck) | No control group + other medications |

| Saito et al. (2010) [17] | case series | 11 free flaps (lower limb) | No control group + other medications |

| Hong & Koshima (2010) [14] | prospective | 25 free flaps using perforators as recipient vessels. (knee joint area) | No control group + other medications |

| Mitate et al. (2011) [15] | prospective | 14 free microvascular flaps (oral cavity) | No control group + dose not mentioned |

| Riva et al. (2012) [20] | retrospective | 1351 free flaps 232 PGE1 283 dextran 836 no antithrombotic (head and neck) | No exclusion criteria |

| Lin et al. (2014) [21] | retrospective | 26 free flaps in 20 patients with hematological disorders (different locations) | No control group + other medications + hematologic disorder |

| Goh 2015 [16] | retrospective | 210 superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flaps (different locations) | No control group + other medications |

| Jin 2019 [22] | prospective | 37 patients undergoing free-flap reconstruction. Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap and anterolateral thigh flap (different locations) | No control group |

| Wang et al. (2020) [23] | retrospective | 21,548 patients, only 8(0.04%) received PGE1 (head and neck) | No control group + other medications + the results, implications, and applicability should be evaluated |

| Park et al. (2020) [24] | prospective observational study | 40 patients with diabetes with free flap (lower limb) | No control group + other medications + multiple factors |

| Jung, Lee & Eun (2024) [25] | retrospective | 12 patients’ reconstructions with lateral arm free flaps (temple area) | No control group |

| Park & Lee (2024) [26] | retrospective | 274 free flaps 142 PGE1 132 no PGE1 (different locations) | Rates of comorbidities and chronic related wounds were higher in the PGE1 cohort in the baseline characteristics |

| Study | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodríguez Vegas, Ruiz Alonso & Terán Saavedra (2007) [12] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Fukuiwa 2008 [19] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Yoshimoto 2010 [13] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Saito et al. (2010) [17] | Moderate | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Hong & Koshima (2010) [14] | Moderate | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Mitate et al. (2011) [15] | Moderate | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Riva et al. (2012) [20] | Moderate | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Lin et al. (2014) [21] | Moderate | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Goh 2015 [16] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Jin 2019 [22] | Moderate | Serious | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Wang et al. (2020) [23] | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low |

| Park et al. (2020) [24] | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Jung, Lee & Eun (2024) [25] | Moderate | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Park & Lee (2024) [26] | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low |

| Area of Reconstruction | No. of Studies | Flaps Used |

|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | 4 | Jejunum, RF, RA LD, ALT, FF, others |

| Oral cavity | 1 | RF, RA, LD |

| Temple area | 1 | LA |

| Lower limb | 2 | LL, LD, SF, ALT, TFL, SCIP, PAP, DPA |

| Knee area | 1 | ALT, MTP |

| Upper limb | 1 | Micro-replantations |

| Different locations (head and neck, breast, trunk, upper limb and lower limb) | 5 | ALT, DIEP, SIEA, TAP, FF, RA, RF, GF, SA, SCIP, VL, TDAP, LD, RASP |

| Name of Drug | Drug Administration | Dose and Days | Time of Injection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodriguez Vegas 2007 [12] | Alprostadil | - Intravenous - Intravenous | - 40 mcg every 12 h - 40 mcg every 12 h 5–7 days | - Intraoperative - Postoperative |

| Fukuiwa 2008 [19] | Alprostadil | Intravenous | 80 mcg for 5 days | Postoperative |

| Yoshimoto 2010 [13] | PGE1 | Intravenous | 80 mcg/day for 5 days | Postoperative |

| Saito et al. (2010) [17] | PGE1 | Continuous infusion in the limb | 40 mcg for 7 days | Postoperative |

| Hong & Koshima (2010) [14] | Lipo-PGE1 Eglandin | Intravenous | 10 mcg + 5% DW for 5 days | Postoperative |

| Mitate et al. (2011) [15] | PGE1 | Intravenous | Twice daily for 7 days | Postoperative |

| Riva et al. (2012) [20] | PGE1, PROMOSTAN | Intravenous | 80 mcg for 5–7 days | Postoperative |

| Lin et al. (2014) [21] | Prostaglandin-E1 | Intravenous (heparin), postoperative (dextran-40 or PGE1) | Not specified | Postoperative |

| Goh 2015 [16] | Prostaglandin-E1 | Intravenous | 10 mcg + 5% DW for 5 days | Postoperative |

| Jin 2019 [22] | Lipo-prostaglandin E1 | Intravenous | Rate of 0.4 μg/h | Postoperative |

| Wang et al. (2020) [23] | Prostaglandin (PGE1), | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| Park et al. (2020) [24] | Lipo-prostaglandin E1 | Intravenous | Rate of 0.4 μg/h | Postoperative |

| Jung et al. (2024) [25] | Alprostadil (PGE1, Eglandin®) | Intravenous | Not specified | Postoperative |

| Park & Lee (2024) [26] | PGE1, Eglandin® | Intravenous | 10 mcg + 100 cc normal saline over 2 h for 7 days | Postoperative |

| Routine or Examination Use | % of Flap Failure | |

|---|---|---|

| Rodríguez Vegas et al. (2007) [12] | Preliminary/early experience using prostaglandins as anticoagulants | 0% |

| Fukuiwa et al. (2008) [19] | Routine use as antithrombotic drug | 5.9% |

| Yoshimoto 2010 [13] | Routine use as antithrombotic drug | 4.8% |

| Saito et al. (2010) [17] | Preliminary/early experience using prostaglandins anticoagulants via continuous infusion | 0% |

| Hong & Koshima (2010) [14] | Routine use as vasodilator | 0% |

| Mitate et al. (2011) [15] | To determine postoperative pattern of blood flow and reveal effects of PGE1 | 0% |

| Riva et al. (2012) [20] | Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) group in which PGE1 was used as an antithrombotic and compared with dextran-40 and control groups | 6% PGE1 6% dextran 5% no antithrombotic therapy |

| Lin et al. (2014) [21] | Routine use as anticoagulant with dextran | 11.5% (3/26) |

| Goh 2015 [16] | Routine | 4.8% |

| Jin 2019 [22] | Use of multiple anticoagulants; PGE1 only used in eight patients | Not specified |

| Wang et al. (2020) [23] | To identify risk factors associated with free-flap failure | 4.1% |

| Park et al. (2020) [24] | To elucidate the role of age, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), duration of diabetes, and flap type in determining the effects of lipo-PGE1 infusion on immediate arterial maximal flow velocity | 7.5% required amputation |

| Jung et al. (2024) [25] | Routine | 0% |

| Park & Lee [16,26] | To identify clinical effectiveness of PGE1 in reducing flap necrosis | Total loss (2.1% vs. 2.3%) Flap: any loss (total, partial, or tip) 7% vs. 18.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

AlQhtani, A. Could Lipo-Prostaglandin E1 Be the Key to Improving Success Rates in Free-Flap Microsurgery? A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010092

AlQhtani A. Could Lipo-Prostaglandin E1 Be the Key to Improving Success Rates in Free-Flap Microsurgery? A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010092

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlQhtani, Abdullh. 2026. "Could Lipo-Prostaglandin E1 Be the Key to Improving Success Rates in Free-Flap Microsurgery? A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010092

APA StyleAlQhtani, A. (2026). Could Lipo-Prostaglandin E1 Be the Key to Improving Success Rates in Free-Flap Microsurgery? A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010092