ChronoimmunoTOX: A Single-Institution Retrospective Study on How the Time of Administration Impacts Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Efficacy and Toxicity in Melanoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tawbi, H.A.; Schadendorf, D.; Lipson, E.J.; Ascierto, P.A.; Matamala, L.; Gutiérrez, E.C.; Rutkowski, P.; Gogas, H.J.; Lao, C.D.; De Menezes, J.J.; et al. Relatlimab and nivolumab versus nivolumab in untreated advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Rutkowski, P.; Cowey, C.L.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Queirolo, P.; Dummer, R.; Butler, M.O.; Hill, A.G.; et al. Final, 10-year outcomes with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.-J.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Schadendorf, D.; Dummer, R.; Smylie, M.; Rutkowski, P.; et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Schachter, J.; Long, G.V.; Arance, A.; Grob, J.J.; Mortier, L.; Daud, A.; Carlino, M.S.; McNeil, C.; Lotem, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2521–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletto, S.; Paruzzo, L.; Nepote, A.; Caravelli, D.; Sangiolo, D.; Carnevale-Schianca, F. Predictive Factors in Metastatic Melanoma Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: From Clinical Practice to Future Perspective. Cancers 2023, 16, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeijmakers, L.L.; Reijers, I.L.; Blank, C.U. Biomarker-driven personalization of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in melanoma: Impact of interferon gamma signature. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 12, e008125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.-K.; Fitzgerald, C.W.; Cho, B.A.; Fitzgerald, B.G.; Han, C.; Koh, E.S.; Pandey, A.; Sfreddo, H.; Crowley, F.; Korostin, M.R.; et al. Prediction of checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy efficacy for cancer using routine blood tests and clinical data. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gougis, P.; Jochum, F.; Abbar, B.; Dumas, E.; Bihan, K.; Lebrun-Vignes, B.; Moslehi, J.; Spano, J.-P.; Laas, E.; Hotton, J.; et al. Clinical spectrum and evolution of immune-checkpoint inhibitors toxicities over a decade—A worldwide perspective. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 70, 102536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, T.M.; Hay, J.L.; Kim, S.Y.; Schofield, E.; Postow, M.A.; Momtaz, P.; Warner, A.B.; Shoushtari, A.N.; Callahan, M.K.; Wolchok, J.D.; et al. Decision-Making and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Melanoma Considering Adjuvant Immunotherapy. Oncologist 2023, 28, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Chen, Y.-P.; Du, X.-J.; Liu, J.-Q.; Huang, C.-L.; Chen, L.; Zhou, G.-Q.; Li, W.-F.; Mao, Y.-P.; Hsu, C.; et al. Comparative safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2018, 363, k4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallardo, D.; Fordellone, M.; Bailey, M.; White, A.; Simeone, E.; Festino, L.; Vanella, V.; Trojaniello, C.; Vitale, M.G.; Ottaviano, M.; et al. Gene-expression signature predicts autoimmune toxicity in metastatic melanoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monson, K.R.; Ferguson, R.; Handzlik, J.E.; Xiong, J.; Dagayev, S.; Morales, L.; Chat, V.; Bunis, A.; Sreenivasaiah, C.; Dolfi, S.; et al. Tyrosine Protein Kinase SYK-Related Gene Signature in Baseline Immune Cells Associated with Adjuvant Immunotherapy–Induced Immune-Related Adverse Events in Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 4412–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wei, B.; Liang, L.; Sheng, Y.; Sun, S.; Sun, X.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Yang, C.; Peng, Y.; et al. The circadian clock component RORA increases PD-L1 expression and promotes immune evasion in melanoma. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 2265–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaboué, A.; Innominato, P.F.; Wreglesworth, N.I.; Duchemann, B.; Adam, R.; Lévi, F.A. Why does circadian timing of administration matter for immune checkpoint inhibitors’ efficacy? Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centanni, M.; Moes, D.J.A.R.; Trocóniz, I.F.; Ciccolini, J.; van Hasselt, J.G.C. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 58, 835–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nose, T.; Funakoshi, Y.; Suto, H.; Nagatani, Y.; Imamura, Y.; Toyoda, M.; Kiyota, N.; Minami, H. Transition of the PD-1 occupancy of nivolumab on T cells after discontinuation and response of nivolumab re-challenge. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 16, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.-J.; Rutkowski, P.; Lao, C.D.; Cowey, C.L.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Dummer, R.; et al. Five-year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.V.; Lipson, E.J.; Hodi, F.S.; Ascierto, P.A.; Larkin, J.; Lao, C.; Grob, J.-J.; Ejzykowicz, F.; Moshyk, A.; Garcia-Horton, V.; et al. First-Line Nivolumab Plus Relatlimab Versus Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma: An Indirect Treatment Comparison Using RELATIVITY-047 and CheckMate 067 Trial Data. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Qian, Y.; Xie, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, D. Predictors of severity and onset timing of immune-related adverse events in cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: A retrospective analysis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1508512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, M.; Naidoo, J. Immune-related adverse events and the balancing act of immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.-Q.; Tang, L.-L.; Mao, Y.-P.; Li, W.-F.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Xu, C.; et al. The Pattern of Time to Onset and Resolution of Immune-Related Adverse Events Caused by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Cancer: A Pooled Analysis of 23 Clinical Trials and 8,436 Patients. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 53, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.C.; Kleber, T.; Brammer, B.; Xu, K.M.; Switchenko, J.M.; Janopaul-Naylor, J.R.; Zhong, J.; Yushak, M.L.; Harvey, R.D.; Paulos, C.M.; et al. Effect of immunotherapy time-of-day infusion on overall survival among patients with advanced melanoma in the USA (MEMOIR): A propensity score-matched analysis of a single-centre, longitudinal study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1777–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, C.; Kartolo, A.; Tong, J.; Hopman, W.; Baetz, T. Association of circadian timing of initial infusions of immune checkpoint inhibitors with survival in advanced melanoma. Immunotherapy 2023, 15, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zeng, L.; Ruan, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Yan, H.; Jiang, W.; Dai, J.; Zou, N.; Xu, S.; et al. Randomized trial of relevance of time-of-day of immunochemotherapy for progression-free and overall survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 8516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascierto, P.A.; Del Vecchio, M.; Merelli, B.; Gogas, H.; Arance, A.M.; Dalle, S.; Cowey, C.L.; Schenker, M.; Gaudy-Marqueste, C.; Pigozzo, J.; et al. Nivolumab for Resected Stage III or IV Melanoma at 9 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Zeng, Q.; Gül, Z.M.; Wang, S.; Pick, R.; Cheng, P.; Bill, R.; Wu, Y.; Naulaerts, S.; Barnoud, C.; et al. Circadian tumor infiltration and function of CD8+ T cells dictate immunotherapy efficacy. Cell 2024, 187, 2690–2702.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Karaboué, A.; Zeng, L.; Lecoeuvre, A.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.-M.; Qin, H.; Danino, G.; Yang, F.; Malin, M.-S.; et al. Overall survival according to time-of-day of combined immuno-chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A bicentric bicontinental study. EBioMedicine 2025, 113, 105607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, S.; Hussein, A.; Kesselman, M.M. The Importance of Timing in Immunotherapy: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e82994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, L.; Gonçalves, D.; Esteban-Casanelles, T.; Barroso, T.; de Pinho, I.S.; Lopes-Brás, R.; Esperança-Martins, M.; Patel, V.; Torres, S.; de Sousa, R.T.; et al. Immunotherapy around the Clock: Impact of Infusion Timing on Stage IV Melanoma Outcomes. Cells 2023, 12, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, P.; Zhang, F.; Wang, G.; Xu, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Guo, Y.; Cai, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Incidence rates of immune-related adverse events and their correlation with response in advanced solid tumours treated with NIVO or NIVO+IPI: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strouse, J.; Chan, K.K.; Baccile, R.; He, G.; Louden, D.K.N.; Giurcanu, M.; Singh, A.; Rieth, J.; Abdel-Wahab, N.; Katsumoto, T.R.; et al. Impact of steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents on tumor outcome in the context of cancer immunotherapy with highlight on melanoma: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1499478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fa’AK, F.; Buni, M.; Falohun, A.; Lu, H.; Song, J.; Johnson, D.H.; Zobniw, C.M.; Trinh, V.A.; Awiwi, M.O.; Tahon, N.H.; et al. Selective immune suppression using interleukin-6 receptor inhibitors for management of immune-related adverse events. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilalta, A.; Arasanz, H.; Rodriguez-Remirez, M.; Lopez, I.; Puyalto, A.; Lecumberri, A.; Baraibar, I.; Corral, J.; Gúrpide, A.; Perez-Gracia, J.; et al. 967P The time of anti-PD-1 infusion improves survival outcomes by fasting conditions simulation in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, S835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaboué, A.; Collon, T.; Pavese, I.; Bodiguel, V.; Cucherousset, J.; Zakine, E.; Innominato, P.F.; Bouchahda, M.; Adam, R.; Lévi, F. Time-Dependent Efficacy of Checkpoint Inhibitor Nivolumab: Results from a Pilot Study in Patients with Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, M.; Hosokai, T.; Tamaoki, M.; Yokoyama, A.; Matsumoto, S.; Muto, M. Timing of the infusion of nivolumab for patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus influences its efficacy. Esophagus 2023, 20, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, B.E.; Andersen, C.; Yuan, Y.; Hong, D.S.; Naing, A.; Karp, D.D.; Yap, T.A.; Ahnert, J.R.; Campbell, E.; Tsimberidou, A.M.; et al. Effect of immunotherapy and time-of-day infusion chronomodulation on survival in advanced cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, C.H.; Montella, T.C.; Ferreira, C.G.M.; De Marchi, P.; Coutinho, L.F.; Duarte, I.L.; e Silva, M.C.; Paes, R.D.; e Silva, G.M.C.; Dienstmann, R. Time-of-day infusion of immunotherapy may impact outcomes in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients (NSCLC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, e21126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortego, I.; Molina-Cerrillo, J.; Pinto, A.; Santoni, M.; Alonso-Gordoa, T.; Criado, M.P.L.; Gonzalez-Morales, A.; Grande, E. Time-of-day infusion of immunotherapy in metastatic urothelial cancer (mUC): Should it be considered to improve survival outcomes? J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, e16541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, A.; Tagliamento, M.; Auclin, E.; Aldea, M.; Frelaut, M.; Levy, A.; Benitez, J.C.; Naltet, C.; Lavaud, P.; Botticella, A.; et al. Clinical outcomes by infusion timing of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2023, 182, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizman, N.; Govindarajan, A.; Zengin, Z.B.; Meza, L.; Tripathi, N.; Sayegh, N.; Castro, D.V.; Chan, E.H.; Lee, K.O.; Prajapati, S.; et al. Association Between Time-of-Day of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Administration and Outcomes in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2023, 21, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.E.; Drayson, M.T.; Taylor, A.E.; Toellner, K.M.; Lord, J.M.; Phillips, A.C. Morning vaccination enhances antibody response over afternoon vaccination: A cluster-randomised trial. Vaccine 2016, 34, 2679–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Zeng, Q.; Li, L.; Zhou, Q.; Li, M.; Mei, J.; Yang, N.; Mo, S.; et al. Time of day influences immune response to an inactivated vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 1215–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazan, G.; Duek, O.A.; Alapi, H.; Mok, H.; Ganninger, A.; Ostendorf, E.; Gierasch, C.; Chodick, G.; Greenberg, D.; Haspel, J.A. Biological rhythms in COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in an observational cohort study of 1.5 million patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e167339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landré, T.; Karaboué, A.; Buchwald, Z.; Innominato, P.; Qian, D.; Assié, J.; Chouaïd, C.; Lévi, F.; Duchemann, B. Effect of immunotherapy-infusion time of day on survival of patients with advanced cancers: A study-level meta-analysis. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 102220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desnoyer, A.; Broutin, S.; Delahousse, J.; Maritaz, C.; Blondel, L.; Mir, O.; Chaput, N.; Paci, A. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies used in oncology: Part 2, immune checkpoint inhibitor antibodies. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 128, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, B.C.; Bill, R.; Okyar, A.; Scheiermann, C.; Hayoz, S.; Olivier, T. Chrono-immunotherapy as a low-hanging fruit for cancer treatment? A call for pragmatic randomized clinical trials. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e010644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Betzalel, G.; Steinberg-Silman, Y.; Stoff, R.; Asher, N.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Schachter, J.; Markel, G. Immunotherapy comes of age in octagenarian and nonagenarian metastatic melanoma patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 108, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huang, Y.; Xue, R.; Li, G.; Li, L.; Liang, L.; Lai, K.; Huang, X.; Qin, Y.; Zheng, Y. T cell-mediated mechanisms of immune-related adverse events induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 213, 104808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banuelos, J.; Lu, N.Z. A gradient of glucocorticoid sensitivity among helper T cell cytokines. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2016, 31, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheijden, R.J.; van Eijs, M.J.M.; May, A.M.; van Wijk, F.; Suijkerbuijk, K.P.M. Immunosuppression for immune-related adverse events during checkpoint inhibition: An intricate balance. Npj Precis. Oncol. 2023, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daetwyler, E.; Wallrabenstein, T.; König, D.; Cappelli, L.C.; Naidoo, J.; Zippelius, A.; Läubli, H. Corticosteroid-resistant immune-related adverse events: A systematic review. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e007409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reijers, I.L.M.; Menzies, A.M.; van Akkooi, A.C.J.; Versluis, J.M.; Heuvel, N.M.J.v.D.; Saw, R.P.M.; Pennington, T.E.; Kapiteijn, E.; van der Veldt, A.A.M.; Suijkerbuijk, K.P.M.; et al. Personalized response-directed surgery and adjuvant therapy after neoadjuvant ipilimumab and nivolumab in high-risk stage III melanoma: The PRADO trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | AM Group (n = 21, n, %) | PM Group (n = 20, n, %) | Pearson Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | p = 0.44 | |||

| F | 18 (44) | 7 (33) | 11 (55) | |

| M | 23 (56) | 14 (67) | 9 (45) | |

| ECOG PS | p = 0.96 | |||

| 0–1 | 37 (90) | 19 (90) | 18 (90) | |

| >1 | 4 (10) | 2 (10) | 2 (10) | |

| Age | p = 0.87 | |||

| <60 | 22 (54) | 11 (52) | 11 (55) | |

| ≥60 y | 19 (46) | 10 (48) | 9 (45) | |

| Stage at diagnosis | p = 0.32 | |||

| I (A,B) | 4 (10) | 3 (14) | 1 (5) | |

| II (A,B,C) | 11 (26) | 5 (24) | 6 (30) | |

| III (A,B,C,D) | 10 (24) | 3 (14) | 7 (35) | |

| IV | 16 (40) | 10 (48) | 6 (30) | |

| Stage at study entry | p = 0.34 | |||

| III | 3 (7) | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | |

| IV | 38 (93) | 19 (90) | 19 (95) | |

| M1a | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | 3 (15) | |

| M1b | 3 (7) | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | |

| M1c | 13 (36) | 9 (47) | 4 (20) | |

| M1d | 19 (50) | 8 (42) | 11 (60) | |

| N° of metastatic sites at study entry | p= 0.07 | |||

| <3 | 28 (68) | 17 (81) | 11 (55) | |

| >3 | 13 (32) | 4 (19) | 9 (45) | |

| BRAF V600 mutational status | p= 0.02 | |||

| Non-mutated | 18 (44) | 13 (60) | 5 (20) | |

| Mutated | 23 (56) | 8 (40) | 15 (80) | |

| Brain metastasis | p = 0.28 | |||

| No | 22 (54) | 13 (62) | 9 (45) | |

| Yes | 19 (46) | 8 (38) | 11 (55) | |

| LDH | p = 0.48 | |||

| <UNV | 8 (20) | 5 (24) | 3 (15) | |

| >UNV | 33 (80) | 16 (76) | 17 (85) | |

| Prior Treatment | p= 0.97 | |||

| Anti BRAF–MEK inhibitors | 6 (15) | 3 (14) | 3(15) | |

| Anti PD-1 | 3 (7) | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | |

| None | 32 (78) | 17 (80) | 15 (75) | |

| Best response at first radiological evaluation | ||||

| CR | 14 (34) | 9 (43) | 5 (27) | p = 0.04 |

| PR | 13 (32) | 8 (38) | 5 (27) | |

| SD | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| PD | 9 (22) | 1 (4) | 8 (44) | |

| NE | 4 (10) | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | |

| DCR | 29 (70) | 18 (93) | 11 (57) | p = 0.01 |

| Site of toxicities | ||||

| Liver | 11 (27) | 5 (23,8) | 6 (30) | p = 0.65 |

| Skin | 7 (17) | 5 (23,8) | 2 (10) | p = 0.24 |

| Gastro-intestinal | 6 (15) | 2 (9,5) | 4 (20) | p = 0.34 |

| Endocrine | 9 (22) | 5 (23,8) | 4 (20) | p = 0.77 |

| Toxicities grade, CTCAE 5.0 | ||||

| G0–G1 | 10(24.4%) | 7 (33) | 3 (15) | p = 0.17 |

| G2–G4 | 31 (75.6%) | 14 (67) | 17 (85) | |

| G0–G2 | 20 (49.8%) | 11 (52) | 9 (65) | p = 0.64 |

| G3–G4 | 21 (51.2%) | 10 (48) | 11 (55) | |

| First-line treatment for toxicities * | 27 * (100) | p = 0.06 | ||

| Steroids | 26 (96) | 11 (52) | 15 (75) | p = 0.04 |

| Tocilizumab | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | |

| None | 14 | 10 (48) | 4 (20) | |

| Second-line treatment for toxicities | 4 * (100) | |||

| Infliximab | 1 (25) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | |

| Tocilizumab | 3 (75) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | |

| Steroid dosage | 26 * (100) | |||

| 1 mg/kg | 23 (88) | 10 (83) | 13 (93) | p = 0.31 |

| 2 mg/kg | 3 (12) | 2 (16) | 1 (7) | |

| Steroid therapy duration * | 26 * (100) | p = 0.08 | ||

| <3 months | 7 (27) | 1 (9) | 6 (40) | |

| >3 months | 17 (65) | 8 (72) | 9 (60) | |

| Not reported | 2 (8) | 2 (19) | 0 (0) |

| PFS | OS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prognostic Variable | Levels | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis |

| Total N. 41 | HR (95% CI), p-Value | HR (95% CI), p-Value | HR (95% CI), p-Value | HR (95% CI), p-Value | |

| ECOG PS | 0–1 | - | - | ||

| >1 | 1.81 (0.53–6.14) p = 0.34 | 0.87 (0.11–6.77), p = 0.896 | |||

| AGE | <60 | - | - | ||

| ≥60 | 1.33 (0.57–3.10) p = 0.51 | 1.63 (0.54–4.94), p = 0.389 | |||

| SEX | F | - | - | ||

| M | 0.56 (0.24–1.30) 0.18 | 0.73 (0.25–2.13), p = 0.568 | |||

| N° of metastatic sites | ≤3 | - | - | ||

| >3 | 2.55 (1.10–5.96) p = 0.030 | 1.78 (0.71–4.44) p = 0.2190 | 2.17 (0.72–6.54), p = 0.168 | 1.38 (0.41–4.59) p = 0.60 | |

| BRAF V600 mutational status | no | - | - | ||

| yes | 1.75 (0.73 4.17) p = 0.21 | 1.04 (0.40–2.67) p = 0.935 | 1.35 (0.45–4.07), p = 0.590 | 0.59(0.16–2.10) p = 0.42 | |

| Brain metastasis | no | ||||

| yes | 1.58 (0.67–3.70) p = 0.28 | 3.29 (0.98–11.03), p = 0.053 | |||

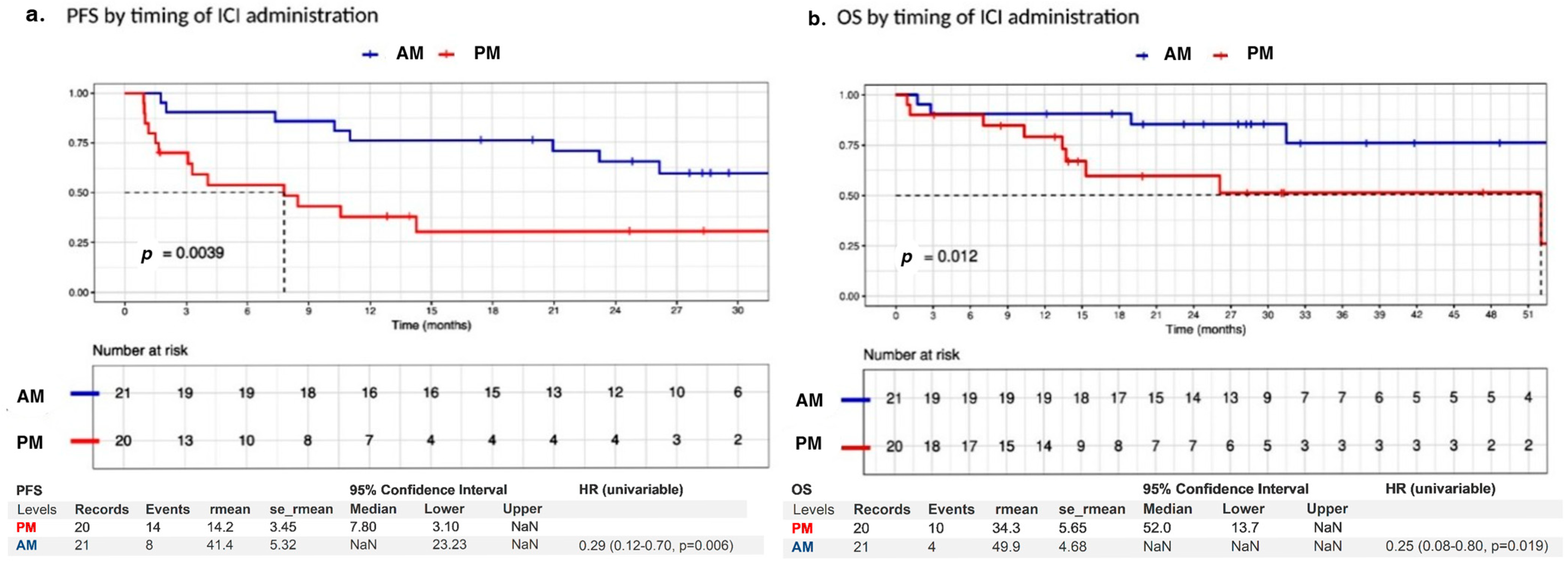

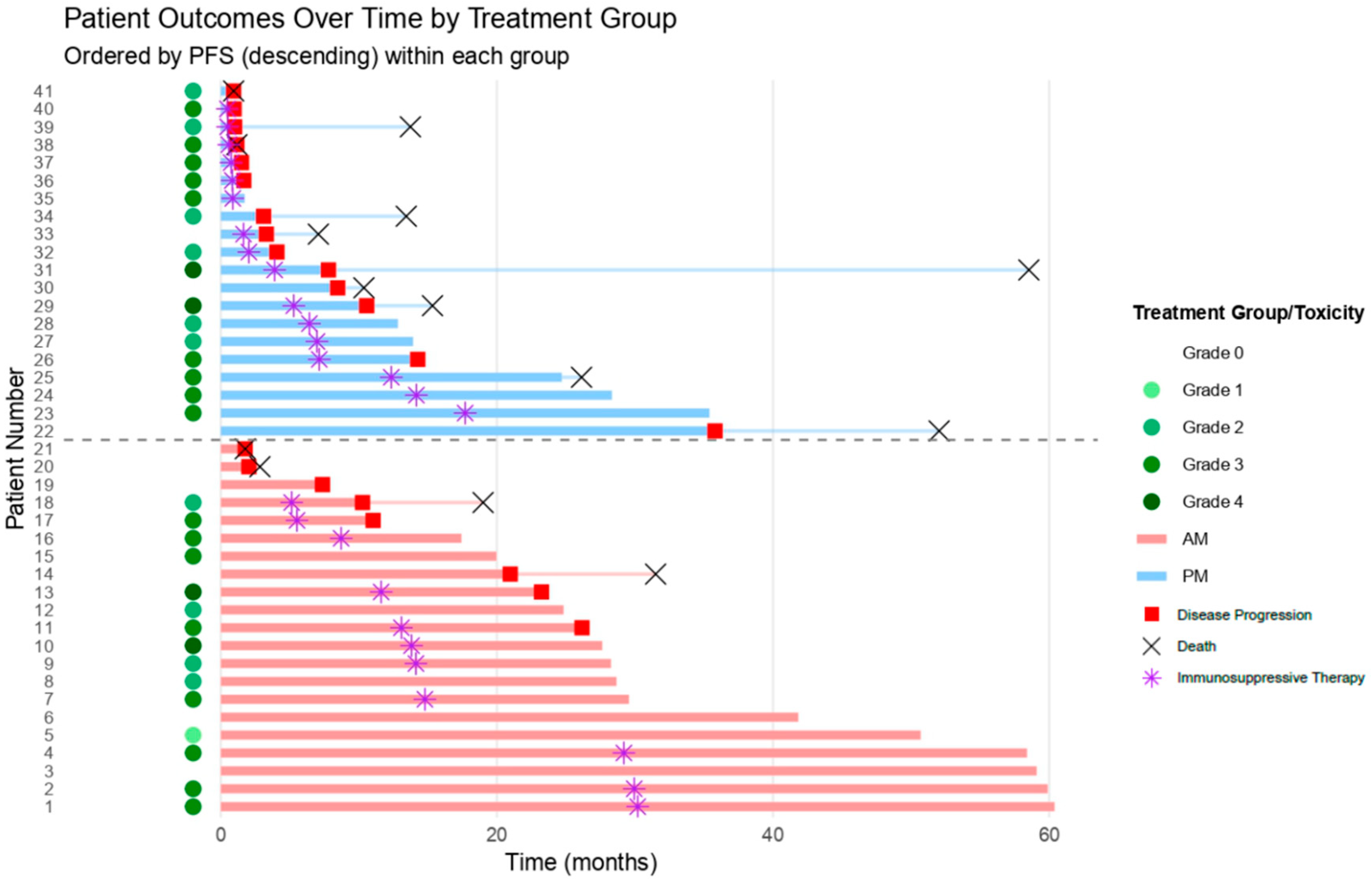

| Time of administration | PM | ||||

| AM | 0.29 (0.12–0.70) p = 0.006 ** | 0.35 (0.14–0.93), p = 0.034 * | 0.25 (0.08–0.80), p = 0.019 ** | 0.22 (0.05–0.88), p = 0.032 ** | |

| Test for interaction | |||||

| N° of metastatic sites | p-value | p-value | |||

| 0.8845074 | 0.5091154 | ||||

| BRAF mutation status | p-value | p-value | |||

| 0.2025199 | 0.3014212 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nepote, A.; Burghgraeve, G.; Pedrani, M.; Gomez Ramos, A.J.; Saporita, I.; Spataro, V.; Espeli, V.; Pereira Mestre, R.; Sangiolo, D.; Imbimbo, M.; et al. ChronoimmunoTOX: A Single-Institution Retrospective Study on How the Time of Administration Impacts Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Efficacy and Toxicity in Melanoma. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010069

Nepote A, Burghgraeve G, Pedrani M, Gomez Ramos AJ, Saporita I, Spataro V, Espeli V, Pereira Mestre R, Sangiolo D, Imbimbo M, et al. ChronoimmunoTOX: A Single-Institution Retrospective Study on How the Time of Administration Impacts Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Efficacy and Toxicity in Melanoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010069

Chicago/Turabian StyleNepote, Alessandro, Gilles Burghgraeve, Martino Pedrani, Anderson Junior Gomez Ramos, Isabella Saporita, Vito Spataro, Vittoria Espeli, Ricardo Pereira Mestre, Dario Sangiolo, Martina Imbimbo, and et al. 2026. "ChronoimmunoTOX: A Single-Institution Retrospective Study on How the Time of Administration Impacts Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Efficacy and Toxicity in Melanoma" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010069

APA StyleNepote, A., Burghgraeve, G., Pedrani, M., Gomez Ramos, A. J., Saporita, I., Spataro, V., Espeli, V., Pereira Mestre, R., Sangiolo, D., Imbimbo, M., & Mangas, C. (2026). ChronoimmunoTOX: A Single-Institution Retrospective Study on How the Time of Administration Impacts Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Efficacy and Toxicity in Melanoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010069