Correlation Between Radiographic and MRI Posterior Tibial Slope Measurement on a Pediatric Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

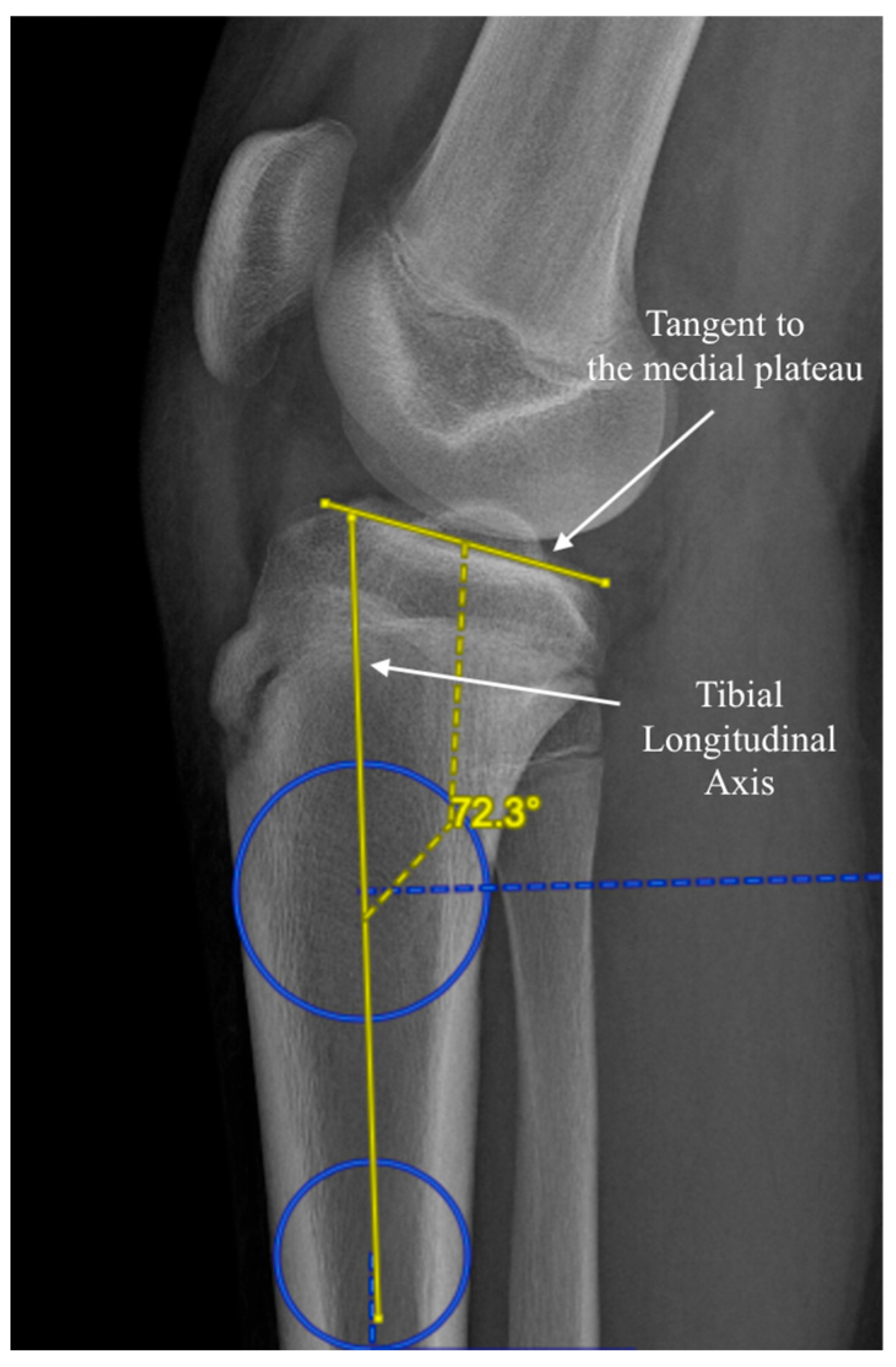

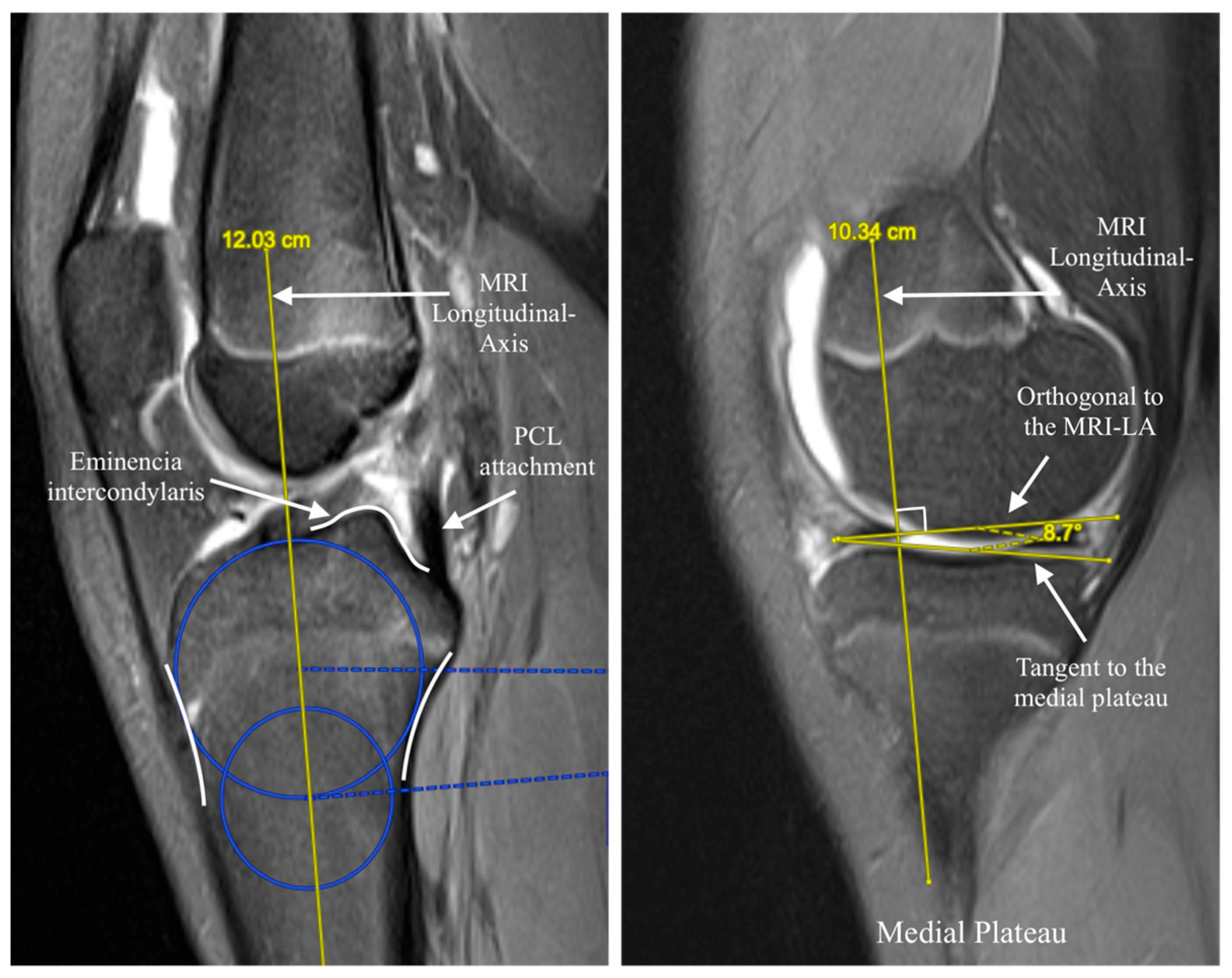

2.2. Measurement Methods

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

3.2. Primary Measurements and Correlation

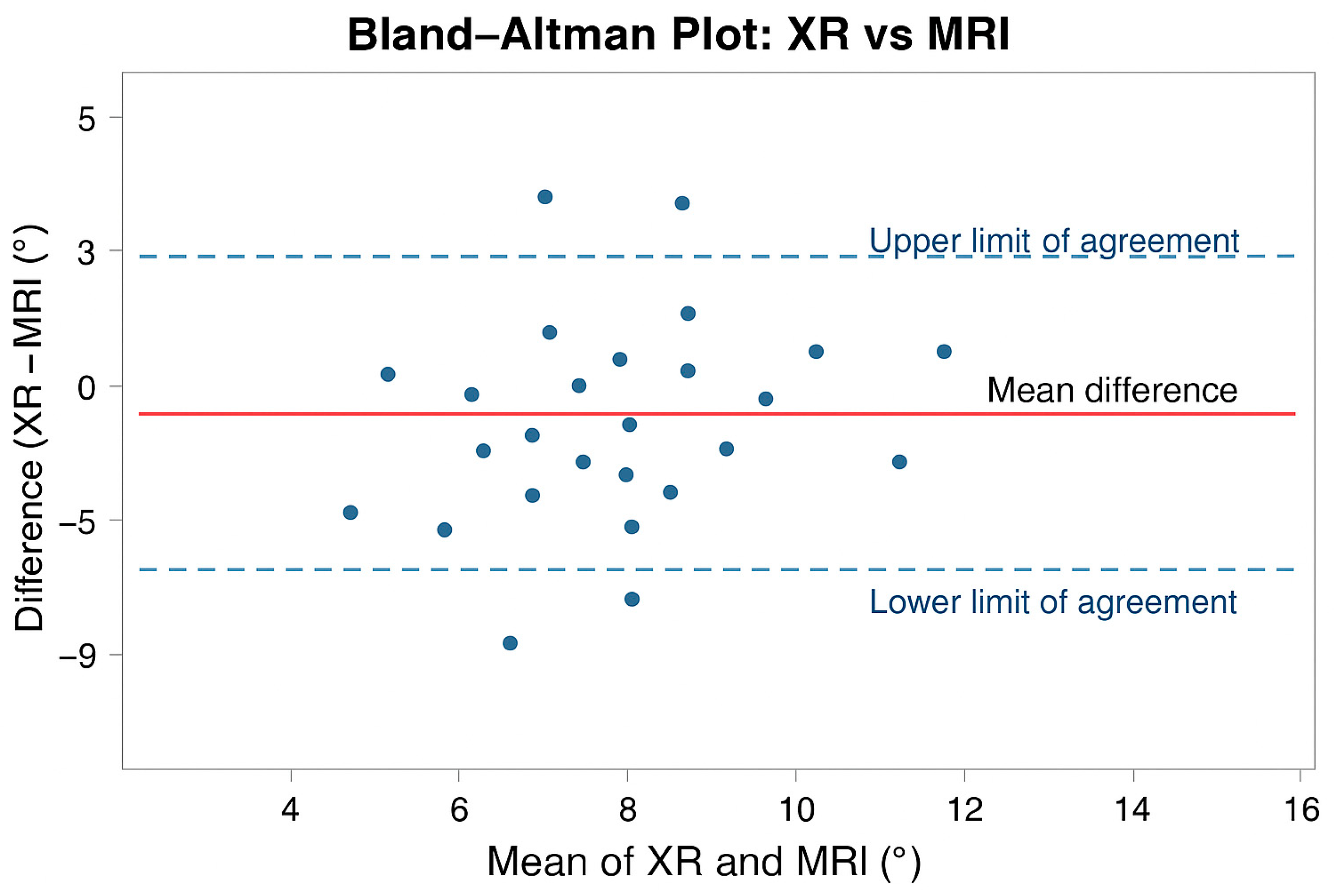

3.3. Agreement Analysis

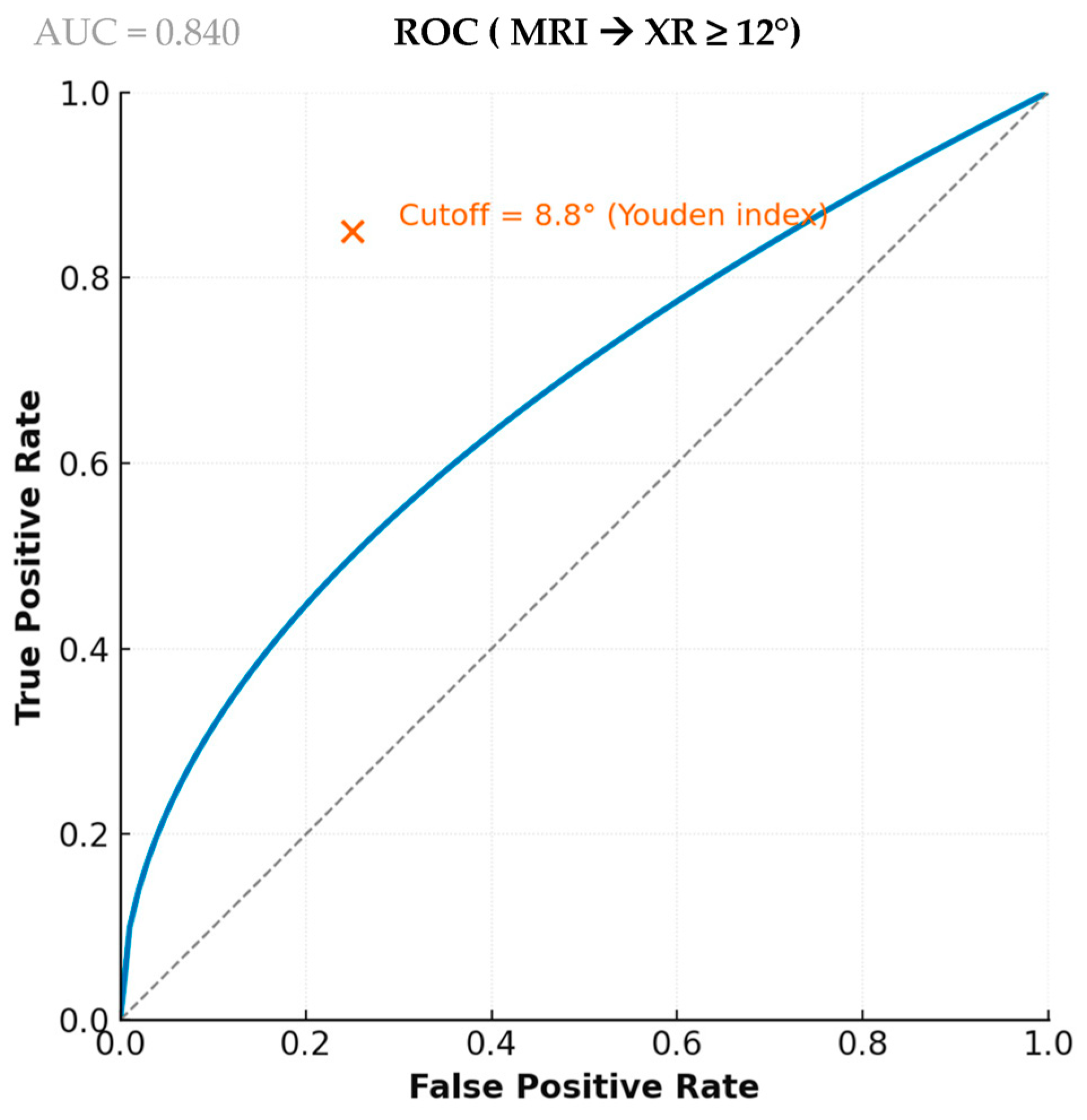

3.4. Diagnostic Performance

3.5. Subgroup Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACL | Anterior Cruciate Ligament |

| ACLR | Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| MPTS | Medial Posterior Tibial Slope |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MRI-LA | MRI Longitudinal Axis |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| PACS | Picture Archiving and Communication System |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| PTS | Posterior Tibial Slope |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TP/FP/TN/FN | True Positive, False Positive, True Negative, False Negative |

| XR | X-Ray |

References

- Shelburne, K.B.; Kim, H.; Sterett, W.I.; Pandy, M.G. Effect of Posterior Tibial Slope on Knee Biomechanics during Functional Activity. J. Orthop. Res. 2011, 29, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, T.; Zeng, C.; Wei, J.; Xie, D.; Yang, Y.; Long, H.; Xu, B.; Qian, Y.; Jiang, S.; et al. Association Between Tibial Plateau Slopes and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: A Meta-Analysis. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2017, 33, 1248–1259.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Borim, F.M.; Lording, T. Increased Posterior Tibial Slope Is a Risk Factor for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury and Graft Failure after Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. J. ISAKOS 2025, 12, 100854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, J.; Yi, Q.; Teng, Y.; Liu, X.; He, J.; Zhang, K.; Wang, L.; Teng, F.; Geng, B.; et al. An Increased Posterior Tibial Slope Is Associated with a Higher Risk of Graft Failure Following ACL Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2022, 30, 2377–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.M.; Salmon, L.J.; Leclerc, E.; Pinczewski, L.A.; Roe, J.P. Posterior Tibial Slope and Further Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in the Anterior Cruciate Ligament–Reconstructed Patient. Am. J. Sports Med. 2013, 41, 2800–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanel, L.; Vieira, T.D.; Ecki, M.; Cucurulo, T.; Fayard, J.-M.; Sonnery-Cottet, B.; Thaunat, M. Assessing Tibial Slope Measurements: A Study of Methodological Consistency and Correlation with ACL Rupture. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utzschneider, S.; Goettinger, M.; Weber, P.; Horng, A.; Glaser, C.; Jansson, V.; Müller, P.E. Development and Validation of a New Method for the Radiologic Measurement of the Tibial Slope. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2011, 19, 1643–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naendrup, J.-H.; Drouven, S.F.; Shaikh, H.S.; Jaecker, V.; Offerhaus, C.; Shafizadeh, S.T.; Pfeiffer, T.R. High Variability of Tibial Slope Measurement Methods in Daily Clinical Practice: Comparisons between Measurements on Lateral Radiograph, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, and Computed Tomography. Knee 2020, 27, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, E.; Norouzian, M.; Birjandinejad, A.; Zandi, R.; Makhmalbaf, H. Measurement of Posterior Tibial Slope Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2017, 5, 435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lipps, D.B.; Wilson, A.M.; Ashton-Miller, J.A.; Wojtys, E.M. Evaluation of Different Methods for Measuring Lateral Tibial Slope Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Am. J. Sports Med. 2012, 40, 2731–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, S.; Van Eck, C.F.; Vyas, N.; Fu, F.H.; Otsuka, N.Y. Increased Medial Tibial Slope in Teenage Pediatric Population with Open Physes and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2011, 19, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dare, D.M.; Fabricant, P.D.; McCarthy, M.M.; Rebolledo, B.J.; Green, D.W.; Cordasco, F.A.; Jones, K.J. Increased Lateral Tibial Slope Is a Risk Factor for Pediatric Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: An MRI-Based Case-Control Study of 152 Patients. Am. J. Sports Med. 2015, 43, 1632–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Kaushal, S.G.; Kocher, M.S.; Kiapour, A.M. Development of Anatomic Risk Factors for ACL Injuries: A Comparison Between ACL-Injured Knees and Matched Controls. Am. J. Sports Med. 2023, 51, 2267–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.C.; Naqvi, A.Z.; Dela Cruz, N.; Gupte, C.M. Predictors of Pediatric Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: The Influence of Steep Lateral Posterior Tibial Slope and Its Relationship to the Lateral Meniscus. Arthroscopy 2021, 37, 1599–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, A.; Pizza, N.; Zambon Bertoja, J.; Macchiarola, L.; Lucidi, G.A.; Dal Fabbro, G.; Zaffagnini, S. Higher Risk of Contralateral Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injury within 2 Years after ACL Reconstruction in Under-18-year-old Patients with Steep Tibial Plateau Slope. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2021, 29, 1690–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Malley, M.P.; Milewski, M.D.; Solomito, M.J.; Erwteman, A.S.; Nissen, C.W. The Association of Tibial Slope and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rupture in Skeletally Immature Patients. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2015, 31, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.; Rahab, R.; Rouanet, T.; Deroussen, F.; Demester, J.; Gouron, R. Is an Excessively High Posterior Tibial Slope a Predisposition to Knee Injuries in Children? Systematic Review of the Literature. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ding, J.; Dai, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, M.; Tian, T.; Deng, X.; Li, B.; Cheng, G.; Liu, J. Radiographic Measurement of the Posterior Tibial Slope in Normal Chinese Adults: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudek, R.; Schmutz, S.; Regenfelder, F.; Fuchs, B.; Koch, P.P. Novel Measurement Technique of the Tibial Slope on Conventional MRI. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2009, 467, 2066–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.D.; Wang, W.; Prentice, H.A.; Funahashi, T.T.; Maletis, G.B. The Association Between Tibial Slope and Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in Patients ≤ 21 Years Old: A Matched Case-Control Study Including 317 Revisions. Am. J. Sports Med. 2019, 47, 3330–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-G.; Jung, M.; Chung, K.; Moon, H.-S.; Jung, S.-H.; Park, Y.; Kim, S.-H. Comparison of Posterior Tibial Slope Measurement Methods Based on 3-Dimensional Reconstruction. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2025, 13, 23259671251378774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwinner, C.; Fuchs, M.; Sentuerk, U.; Perka, C.F.; Walter, T.C.; Schatka, I.; Rogasch, J.M.M. Assessment of the Tibial Slope Is Highly Dependent on the Type and Accuracy of the Preceding Acquisition. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2019, 139, 1691–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amerinatanzi, A.; Summers, R.; Ahmadi, K.; Goel, V.K.; Hewett, T.E.; Nyman, E. A Novel 3D Approach for Determination of Frontal and Coronal Plane Tibial Slopes from MR Imaging. Knee 2017, 24, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, T.E.; Driskill, E.K.; Tagliero, A.J.; Klosterman, E.L.; Ramamurti, P.; Reahl, G.B.; Miller, M.D. Combined Tibial Deflexion Osteotomy and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Improves Knee Function and Stability: A Systematic Review. J. ISAKOS 2024, 9, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejour, D.; Saffarini, M.; Demey, G.; Baverel, L. Tibial Slope Correction Combined with Second Revision ACL Produces Good Knee Stability and Prevents Graft Rupture. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2015, 23, 2846–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoto, R.; Alm, L.; Drenck, T.C.; Frings, J.; Krause, M.; Frosch, K.-H. Slope-Correction Osteotomy with Lateral Extra-Articular Tenodesis and Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Is Highly Effective in Treating High-Grade Anterior Knee Laxity. Am. J. Sports Med. 2020, 48, 3478–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| N pairs | 108 |

| Male, n (%) | 74 (68.5) |

| Female, n (%) | 34 (31.5) |

| Age (years), | 13.9 ± 2.0 |

| Weight (kg), | 58.0 ± 14.1 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.1 ± 4.1 |

| XR PTS (°) | 10.2 ± 3.1 |

| MRI PTS (°) | 8.4 ± 2.8 |

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.841 (0.760–0.922) |

| Best MRI cutoff (°) | 8.8 |

| True Positive | 31 |

| False Positive | 12 |

| False Negative | 7 |

| True Negative | 58 |

| Sensitivity | 81.6% |

| Specificity | 82.9% |

| Positive Predictive Value | 72.1% |

| Negative Predictive Value | 89.2% |

| Accuracy | 82.4% |

| XR ≥ 12° | XR < 12° | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRI ≥ 8.8° | 31 | 12 | 43 |

| MRI < 8.8° | 7 | 58 | 65 |

| Total | 38 | 70 | 108 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Peufly, C.; Chaal, L.; Chouffani, E.; Patel, R.; Pesenti, S.; Ollivier, M.; Piercecchi, A. Correlation Between Radiographic and MRI Posterior Tibial Slope Measurement on a Pediatric Population. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010064

Peufly C, Chaal L, Chouffani E, Patel R, Pesenti S, Ollivier M, Piercecchi A. Correlation Between Radiographic and MRI Posterior Tibial Slope Measurement on a Pediatric Population. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010064

Chicago/Turabian StylePeufly, Clémence, Lyes Chaal, Elie Chouffani, Romir Patel, Sebastien Pesenti, Matthieu Ollivier, and Antoine Piercecchi. 2026. "Correlation Between Radiographic and MRI Posterior Tibial Slope Measurement on a Pediatric Population" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010064

APA StylePeufly, C., Chaal, L., Chouffani, E., Patel, R., Pesenti, S., Ollivier, M., & Piercecchi, A. (2026). Correlation Between Radiographic and MRI Posterior Tibial Slope Measurement on a Pediatric Population. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010064