Real-World Safety of Cyproheptadine-Based Appetite Stimulants: An Electronic Health Record-Based Retrospective Cohort Study in Adult Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Sources

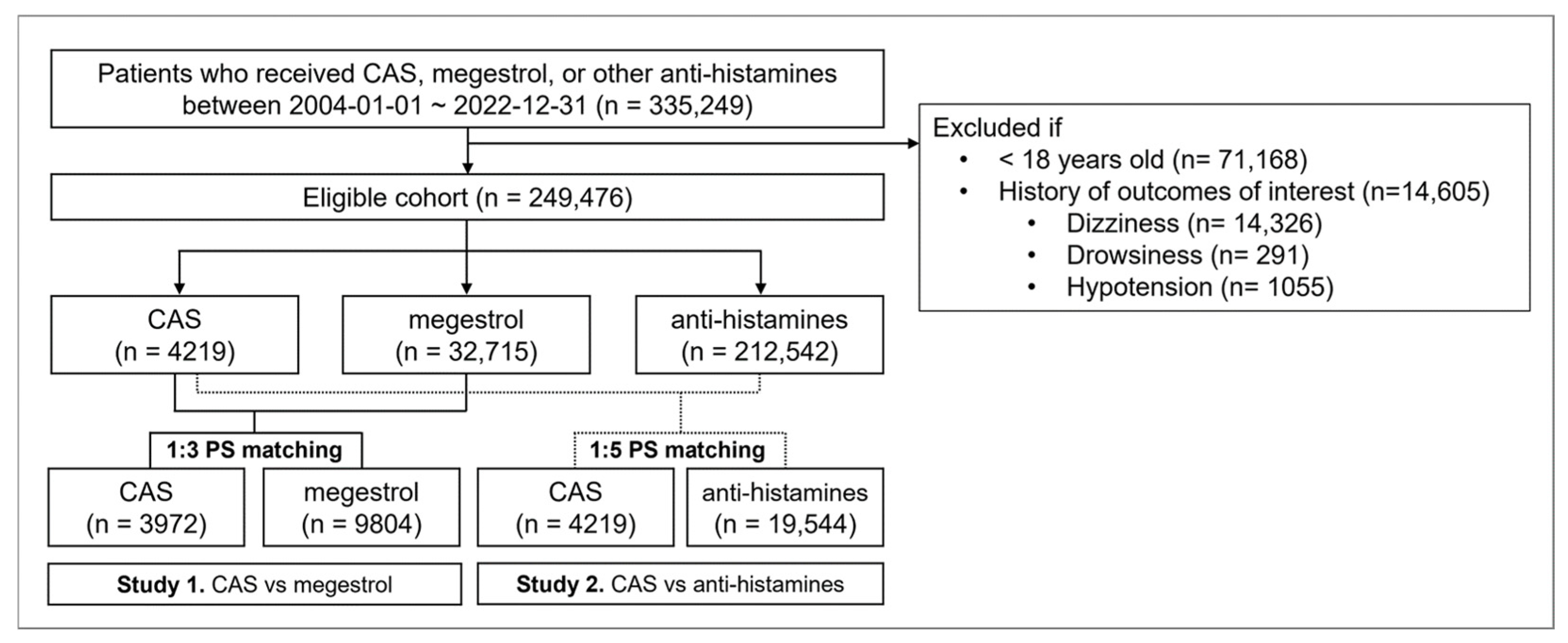

2.2. Patient Selection and Follow-Up

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Sensitivity and Subgroup Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Comparative Safety Profile of CAS and Megestrol

3.3. Comparative Safety Profile of CAS and Antihistamines

3.4. Subgroup Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAS | Cyproheptadine-based appetite stimulant |

| CDM | Common data model |

| aHR | Adjusted hazard ratio |

References

- Norman, K.; Haß, U.; Pirlich, M. Malnutrition in Older Adults-Recent Advances and Remaining Challenges. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, F.; Picca, A.; Calvani, R.; Marzetti, E. Anorexia of Aging: Assessment and Management. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2017, 33, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leij-Halfwerk, S.; Verwijs, M.H.; van Houdt, S.; Borkent, J.W.; Guaitoli, P.; Pelgrim, T.; Heymans, M.W.; Power, L.; Visser, M.; Corish, C.A.; et al. Prevalence of protein-energy malnutrition risk in European older adults in community, residential and hospital settings, according to 22 malnutrition screening tools validated for use in adults ≥ 65 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2019, 126, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmi, K.A.; Eckert, E.; Falk, J.R. Cyproheptadine for anorexia nervosa. Lancet 1982, 1, 1357–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.E.; Norris, M.L.; Robinson, A.; Spettigue, W.; Morrissey, M.; Isserlin, L. Use of cyproheptadine to stimulate appetite and body weight gain: A systematic review. Appetite 2019, 137, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DailyMed Cyproheptadine Hydrochloride—Drug Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2024. Available online: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=80e13d3f-f4db-4bb4-95d5-5ac1afa70e7e (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS). Cyproheptadine Cinfa 4 mg Comprimidos: Prospecto. CIMA: Centro de Información Online de Medicamentos. Available online: https://cima.aemps.es/cima/dochtml/p/35622/Prospecto_35622.html (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Kim, S.Y.; Yun, J.M.; Lee, J.W.; Cho, Y.G.; Cho, K.H.; Park, Y.G.; Cho, B. Efficacy and tolerability of cyproheptadine in poor appetite: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin. Ther. 2021, 43, 1757–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Garcia, V.; López-Briz, E.; Carbonell Sanchis, R.; Gonzalvez Perales, J.L.; Bort-Marti, S. Megestrol acetate for treatment of anorexia–cachexia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD004310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, L.; Brunetti, L.; Roberts, S.; Ziegler, J. A review of the efficacy of appetite-stimulating medications in hospitalized adults. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2023, 38, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Jo, B.; Woo, H.; Im, Y.; Park, R.W.; Park, C. Chronic disease prediction using the common data model: Development study. JMIR AI 2022, 1, e41030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komen, J.J.; Belitser, S.V.; Wyss, R.; Schneeweiss, S.; Taams, A.C.; Pajouheshnia, R.; Forslund, T.; Klungel, O.H. Greedy caliper propensity score matching can yield variable estimates of the treatment–outcome association: A simulation study. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2021, 30, 934–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, P.C. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat. Med. 2009, 28, 3083–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, D.T.; Kasper, J.D.; Potter, D.E.; Lyles, A. Potentially inappropriate medication prescriptions among elderly nursing home residents: Their scope and associated resident and facility characteristics. Health Serv. Res. 2004, 39, 1257–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, J.L.; Salow, M.J.; Angelini, M.C.; McGlinchey, R.E. The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.K.; Lee, Y.J. Prescription patterns of anticholinergic agents and their associated factors in Korean elderly patients with dementia. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2013, 35, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisdale, J.E. Cyproheptadine: Drug Information. UpToDate. Available online: https://www-uptodate-com.libproxy.dcmc.co.kr/contents/cyproheptadine-drug-information?search=cyproheptadine&source=panel_search_result&selectedTitle=1~45&usage_type=panel&kp_tab=drug_general&display_rank=1#F155687 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Leurs, R.; Smit, M.J.; Timmerman, H. Histamine receptors: Specific ligands, receptor biochemistry, and signal transduction. In Histamine and H1-Receptor Antagonists in Allergic Disease; Simons, F.E.R., Ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Marie Gavioli, E.; Burger, A.; Gamaleldin, A.; Eladghm, N.; Vider, E. Propensity score-matching analysis comparing safety outcomes of appetite-stimulating medications in oncology patients. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 6299–6305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinnell, M.; Price, K.N.; Shah, A.; Butler, D.C. Antihistamine safety in older adult dermatologic patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 87, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.; Klimek, L.; Hörmann, K. Pharmacological management of allergic rhinitis in the elderly: Safety issues with oral antihistamines. Drugs Aging 2005, 22, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, M.L.; Hossaini, R.; Tolar, C.; Gaviola, M.L. Efficacy and safety of appetite-stimulating medications in the inpatient setting. Ann. Pharmacother. 2019, 53, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R.J.; European Multicentre Study Group. Efficacy and tolerability comparison of ebastine 10 and 20 mg with loratadine 10 mg: A double-blind, randomised study in patients with perennial allergic rhinitis. Clin. Drug Investig. 1998, 16, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBuske, L.M. Pharmacology of desloratadine: Special characteristics. Clin. Drug Investig. 2002, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliner, M.A. H1-antihistamines in the elderly. In Histamine and H1-Antihistamines in Allergic Disease; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; Volume 17, pp. 465–481. [Google Scholar]

- Klimek, L.; Hundorf, I. Levocetirizine bei allergischen Erkrankungen. Allergologie 2002, 25, S1–S7. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, R.D.; Pearce, G.L.; Dunn, N.; Shakir, S. Sedation with “non-sedating” antihistamines: Four prescription-event monitoring studies in general practice. BMJ 2000, 320, 1184–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCue, J.D. Safety of antihistamines in the treatment of allergic rhinitis in elderly patients. Arch. Fam. Med. 1996, 5, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picca, A.; Calvani, R.; Coelho-Júnior, H.J.; Landi, F.; Marzetti, E. Anorexia of aging: Metabolic changes and biomarker discovery. Clin. Interv. Aging 2022, 17, 1761–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, G.L.; Mason, J.; Compton, D.; Stewart, J.; Ricard, N. The efficacy and safety of fexofenadine HCl and pseudoephedrine, alone and in combination, in seasonal allergic rhinitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1999, 104, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Anker, S.D.; Argiles, J.; Aversa, Z.; Bauer, J.M.; Biolo, G.; Boirie, Y.; Bosaeus, I.; Cederholm, T.; Costelli, P.; et al. Consensus definition of sarcopenia, cachexia and pre-cachexia: Joint document elaborated by Special Interest Groups (SIG) “cachexia-anorexia in chronic wasting diseases” and “nutrition in geriatrics”. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 29, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fick, D.M.; Semla, T.P.; Steinman, M.; Beizer, J.; Brandt, N.; Dombrowski, R. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 674–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, V.; Massy, N.; Vegas, N.; Gras, V.; Chalouhi, C.; Tavolacci, M.-P.; Abadie, V. Safety of cyproheptadine, an orexigenic drug: Analysis of the French National Pharmacovigilance Database and systematic review. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 712413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, G.S.; Roehrs, T.A.; Rosenthal, L.; Koshorek, G.; Roth, T. Tolerance to daytime sedative effects of H1 antihistamines. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2002, 22, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pre-Match | Post-Match | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAS (n = 4219) | Megestrol (n = 32,715) | STD | CAS (n = 3972) | Megestrol (n = 9804) | STD | ||

| Demo-graphic | Sex | 1634 (38.7%) | 18,221 (55.7%) | −0.3 | 1578 (39.7%) | 4261 (43.5%) | −0.08 |

| Age | 70.5 ± 13.3 | 66.2 ± 12.4 | 0.3 | 70.3 ± 13.3 | 69.8 ± 11.5 | 0.04 | |

| Prescription count | 337.7 ± 751.5 | 132.9 ± 192.9 | 0.4 | 251.8 ± 416.6 | 182.4 ± 292.1 | 0.1 | |

| Co-morbidities | Cerebrovascular | 735 (17.4%) | 3141 (9.6%) | −0.2 | 650 (16.4%) | 1370 (14.0%) | −0.08 |

| Depression | 564 (13.4%) | 511 (1.6%) | −0.5 | 405 (10.2%) | 433 (4.4%) | −0.2 | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 193 (4.6%) | 1146 (3.5%) | −0.05 | 177 (4.5%) | 430 (4.4%) | −0.004 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 484 (11.5%) | 1223 (3.7%) | −0.3 | 425 (10.7%) | 803 (8.2%) | −0.1 | |

| Hypertension | 542 (12.8%) | 2435 (7.4%) | −0.2 | 485 (12.2%) | 1085 (11.1%) | −0.04 | |

| Schizophrenia | 63 (1.5%) | 95 (0.3%) | −0.1 | 42 (1.1%) | 65 (0.7%) | −0.04 | |

| Anxiety | 1654 (39.2%) | 14,860 (45.4%) | 0.1 | 1515 (38.1%) | 3692 (37.7%) | −0.001 | |

| Co-medications | ACEi/ARB | 945 (22.4%) | 5621 (17.2%) | −0.1 | 872 (22.0%) | 2110 (21.5%) | −0.01 |

| Beta-blocker | 812 (19.2%) | 6012 (18.4%) | −0.02 | 740 (18.6%) | 1768 (18.0%) | −0.02 | |

| Calcium channel blocker | 1241 (29.4%) | 9687 (29.6%) | 0.004 | 1161 (29.2%) | 2864 (29.2%) | −0.0004 | |

| Other anti-hypertensives | 36 (0.9%) | 340 (1.0%) | 0.02 | 32 (0.8%) | 77 (0.8%) | −0.002 | |

| Loop diuretic | 660 (15.6%) | 7007 (21.4%) | 0.1 | 617 (15.5%) | 1562 (15.9%) | 0.01 | |

| Other diuretics | 917 (21.7%) | 8552 (26.1%) | 0.1 | 861 (21.7%) | 2133 (21.8%) | 0.002 | |

| Metformin | 532 (12.6%) | 3111 (9.5%) | −0.1 | 502 (12.6%) | 1214 (12.4%) | −0.008 | |

| Sulfonylurea | 301 (7.1%) | 2548 (7.8%) | 0.02 | 282 (7.1%) | 724 (7.4%) | 0.01 | |

| DPP-4 inhibitor | 379 (9.0%) | 1768 (5.4%) | −0.1 | 353 (8.9%) | 852 (8.7%) | −0.008 | |

| SGLT-2 inhibitor | 48 (1.1%) | 127 (0.4%) | −0.09 | 46 (1.2%) | 98 (1.0%) | −0.02 | |

| GLP-1 agonist | 2 (0.0%) | 8 (0.0%) | −0.01 | 2 (0.1%) | 6 (0.1%) | 0.006 | |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor | 26 (0.6%) | 336 (1.0%) | 0.05 | 26 (0.7%) | 72 (0.7%) | 0.009 | |

| Meglitinides | 13 (0.3%) | 119 (0.4%) | 0.01 | 11 (0.3%) | 28 (0.3%) | 0.002 | |

| Insulin | 485 (11.5%) | 4066 (12.4%) | 0.03 | 459 (11.6%) | 1195 (12.2%) | 0.02 | |

| Erythropoietin stimulating agent | 163 (3.9%) | 917 (2.8%) | −0.06 | 135 (3.4%) | 335 (3.4%) | 0.001 | |

| Iron supplement | 87 (2.1%) | 384 (1.2%) | −0.07 | 86 (2.2%) | 208 (2.1%) | −0.003 | |

| Anticonvulsant | 195 (4.6%) | 597 (1.8%) | −0.16 | 167 (4.2%) | 317 (3.2%) | −0.06 | |

| Antidepressant | 793 (18.8%) | 1610 (4.9%) | −0.4 | 649 (16.3%) | 1070 (10.9%) | −0.2 | |

| Antipsychotic | 695 (16.5%) | 2589 (7.9%) | −0.3 | 586 (14.8%) | 1134 (11.6%) | −0.1 | |

| Laboratory findings | estimated GFR | 80.8 ± 30.2 | 86.5 ± 31.3 | −0.07 | 81.7 ± 30.0 | 76.1 ± 26.7 | −0.05 |

| Iron saturation | 29.4 ± 21.2 | 28.1 ± 22.6 | 0.1 | 29.3 ± 21.5 | 28.9 ± 21.5 | 0.02 | |

| Vitamin B12 | 1067.2 ± 1299.9 | 1601.6 ± 7183.5 | 0.05 | 1087.6 ± 1358.7 | 1860.4 ± 10,951.9 | −0.01 | |

| Hemoglobin | 11.7 ± 2.0 | 11.3 ± 1.9 | −0.1 | 11.7 ± 2.0 | 11.2 ± 1.9 | 0.01 | |

| Ferritin | 574.4 ± 2005.6 | 661.3 ± 3595.8 | 0.01 | 598.7 ± 2101.3 | 637.7 ± 5630.9 | −0.004 | |

| Hba1c | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 6.5 ± 1.3 | 0.4 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 6.4 ± 1.2 | 0.07 | |

| HDL | 50.5 ± 16.9 | 46.4 ± 16.6 | 0.5 | 50.1 ± 16.8 | 49.8 ± 16.7 | 0.1 | |

| Cortisol | 15.9 ± 11.2 | 17.3 ± 24.5 | 0.07 | 16.0 ± 11.2 | 17.8 ± 29.6 | 0.02 | |

| Cortisol30 | 20.6 ± 9.7 | 22.5 ± 10.7 | 0.09 | 20.6 ± 9.9 | 23.9 ± 11.6 | 0.03 | |

| Cortisol90 | 10.7 ± 7.4 | 20.4 ± 11.5 | −0.01 | 10.7 ± 7.4 | 20.5 ± 1.4 | 0.003 | |

| Serum Na | 138.3 ± 4.2 | 137.1 ± 4.4 | −0.2 | 138.3 ± 4.2 | 137.7 ± 4.2 | 0.003 | |

| Total cholesterol | 161.1 ± 45.7 | 157.1 ± 47.7 | −0.2 | 160.8 ± 46.0 | 156.0 ± 45.6 | 0.06 | |

| Folate | 12.7 ± 14.4 | 13.1 ± 56.2 | 0.1 | 12.6 ± 14.5 | 15.1 ± 84.4 | 0.07 | |

| Mean blood pressure | 107.4 ± 16.2 | 109.6 ± 16.0 | 0.1 | 107.2 ± 16.1 | 112.5 ± 16.7 | 0.02 | |

| Pre-Match | Post-Match | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAS (n = 4219) | Antihistamine (n = 212,542) | STD | CAS (n = 4219) | Antihistamine (n = 19,544) | STD | ||

| Demo-graphic | Sex | 1634 (38.7%) | 93,583 (44.0%) | −0.1 | 1634 (38.7%) | 7848 (40.2%) | −0.03 |

| Age | 70.5 ± 13.3 | 51.0 ± 17.7 | 1.2 | 70.5 ± 13.3 | 70.0 ± 12.6 | 0.03 | |

| Prescription count | 337.7 ± 751.5 | 141.4 ± 344.2 | 0.3 | 337.7 ± 751.5 | 298.1 ± 651.7 | 0.07 | |

| Co-morbidities | Cerebrovascular | 735 (17.4%) | 14,915 (7.0%) | −0.3 | 735 (17.4%) | 3145 (16.1%) | −0.04 |

| Depression | 564 (13.4%) | 3240 (1.5%) | −0.5 | 564 (13.4%) | 1739 (8.9%) | −0.2 | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 193 (4.6%) | 5218 (2.5%) | −0.1 | 193 (4.6%) | 899 (4.6%) | 0.001 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 484 (11.5%) | 11,015 (5.2%) | −0.2 | 484 (11.5%) | 2155 (11.0%) | −0.01 | |

| Hypertension | 542 (12.8%) | 13,529 (6.4%) | −0.2 | 542 (12.8%) | 2438 (12.5%) | −0.01 | |

| Schizophrenia | 63 (1.5%) | 1329 (0.6%) | −0.08 | 63 (1.5%) | 238 (1.2%) | −0.03 | |

| Anxiety | 1654 (39.2%) | 39,080 (18.4%) | −0.5 | 1654 (39.2%) | 7292 (37.3%) | −0.04 | |

| Co-medications | ACEi/ARB | 945 (22.4%) | 19,426 (9.1%) | −0.4 | 945 (22.4%) | 4238 (21.7%) | −0.02 |

| Beta-blocker | 812 (19.2%) | 18,053 (8.5%) | −0.3 | 812 (19.2%) | 3579 (18.3%) | −0.03 | |

| Calcium channel blocker | 1241 (29.4%) | 23,347 (11.0%) | −0.5 | 1241 (29.4%) | 5541 (28.4%) | −0.03 | |

| Other anti-hypertensives | 36 (0.9%) | 1211 (0.6%) | −0.03 | 36 (0.9%) | 164 (0.8%) | −0.001 | |

| Loop diuretic | 660 (15.6%) | 11,635 (5.5%) | −0.3 | 660 (15.6%) | 2894 (14.8%) | −0.03 | |

| Other diuretics | 917 (21.7%) | 17,101 (8.0%) | −0.4 | 917 (21.7%) | 4073 (20.8%) | −0.03 | |

| Metformin | 532 (12.6%) | 8402 (4.0%) | −0.3 | 532 (12.6%) | 2423 (12.4%) | −0.01 | |

| Sulfonylurea | 301 (7.1%) | 6069 (2.9%) | −0.2 | 301 (7.1%) | 1408 (7.2%) | 0.003 | |

| DPP-4 inhibitor | 379 (9.0%) | 4706 (2.2%) | −0.3 | 379 (9.0%) | 1711 (8.8%) | −0.01 | |

| SGLT-2 inhibitor | 48 (1.1%) | 511 (0.2%) | −0.1 | 48 (1.1%) | 207 (1.1%) | −0.01 | |

| GLP-1 agonist | 2 (0.0%) | 65 (0.0%) | −0.009 | 2 (0.0%) | 11 (0.1%) | 0.004 | |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor | 26 (0.6%) | 799 (0.4%) | −0.03 | 26 (0.6%) | 117 (0.6%) | −0.003 | |

| Meglitinides | 13 (0.3%) | 396 (0.2%) | −0.02 | 13 (0.3%) | 63 (0.3%) | 0.003 | |

| Insulin | 485 (11.5%) | 7858 (3.7%) | −0.3 | 485 (11.5%) | 2137 (10.9%) | −0.02 | |

| Erythropoietin stimulating agent | 163 (3.9%) | 2853 (1.3%) | −0.2 | 163 (3.9%) | 683 (3.5%) | −0.02 | |

| Iron supplement | 87 (2.1%) | 437 (0.2%) | −0.2 | 87 (2.1%) | 248 (1.3%) | −0.08 | |

| Anticonvulsant | 195 (4.6%) | 3373 (1.6%) | −0.2 | 195 (4.6%) | 804 (4.1%) | −0.02 | |

| Antidepressant | 793 (18.8%) | 7556 (3.6%) | −0.5 | 793 (18.8%) | 2905 (14.9%) | −0.1 | |

| Antipsychotic | 695 (16.5%) | 10,372 (4.9%) | −0.4 | 695 (16.5%) | 2587 (13.2%) | −0.1 | |

| Laboratory findings | estimated GFR | 80.8 ± 30.2 | 89.0 ± 27.4 | 0.3 | 80.8 ± 30.2 | 79.2 ± 28.5 | 0.02 |

| Iron saturation | 29.4 ± 21.2 | 30.0 ± 21.4 | 0.3 | 29.4 ± 21.2 | 30.4 ± 21.6 | 0.02 | |

| Vitamin B12 | 1067.2 ± 1299.9 | 1167.5 ± 3306.7 | 0.3 | 1067.2 ± 1299.9 | 1377.2 ± 5345.6 | 0.05 | |

| Hemoglobin | 11.7 ± 2.0 | 13.2 ± 2.0 | −0.02 | 11.7 ± 2.0 | 12.1 ± 2.0 | −0.01 | |

| Ferritin | 574.4 ± 2005.6 | 521.6 ± 2790.1 | 0.08 | 574.4 ± 2005.6 | 586.3 ± 4616.3 | 0.001 | |

| Hba1c | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 0.6 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 6.3 ± 1.1 | 0.03 | |

| HDL | 50.5 ± 16.9 | 52.7 ± 15.6 | 0.4 | 50.5 ± 16.9 | 51.0 ± 16.0 | 0.02 | |

| Cortisol | 15.9 ± 11.2 | 14.2 ± 26.2 | 0.1 | 15.9 ± 11.2 | 15.4 ± 11.9 | 0.02 | |

| Cortisol30 | 20.6 ± 9.7 | 20.2 ± 10.8 | 0.2 | 20.6 ± 9.7 | 21.4 ± 11.5 | 0.03 | |

| Cortisol90 | 10.7 ± 7.4 | 18.6 ± 10.3 | −0.03 | 10.7 ± 7.4 | 21.4 ± 6.7 | −0.005 | |

| Serum Na | 138.3 ± 4.2 | 139.8 ± 3.0 | 0.5 | 138.3 ± 4.2 | 139.5 ± 3.5 | 0.004 | |

| Total cholesterol | 161.1 ± 45.7 | 178.1 ± 41.1 | 0.05 | 161.1 ± 45.7 | 163.3 ± 42.1 | 0.004 | |

| Folate | 12.7 ± 14.4 | 13.1 ± 26.0 | 0.3 | 12.7 ± 14.4 | 15.6 ± 43.9 | 0.08 | |

| Mean blood pressure | 107.4 ± 16.2 | 110.5 ± 16.5 | 0.4 | 107.4 ± 16.2 | 113.2 ± 17.0 | 0.02 | |

| (a) CAS vs. megestrol | |||||

| Outcomes | Patient-Year | Events | Rate per 1000 Patient-Years | aHR (95% CI) | |

| Dizziness | |||||

| Megestrol | 2436 | 75 | 30.8 | 1.02 (0.70–1.50) | |

| CAS | 2172 | 63 | 29.0 | ||

| Sedation | |||||

| Megestrol | 2452 | 15 | 6.1 | 0.53 (0.19–1.54) | |

| CAS | 2197 | 8 | 3.6 | ||

| Hypotension | |||||

| Megestrol | 2448 | 27 | 11.0 | 0.70 (0.34–1.44) | |

| CAS | 2199 | 13 | 5.9 | ||

| aHR: age, sex adjusted. | |||||

| (b) CAS vs. antihistamines | |||||

| Outcomes | Patient-Year | Events | Rate per 1000 Patient-Years | aHR (95% CI) | |

| Dizziness | |||||

| Antihistamines | 5412 | 303 | 56.0 | 0.74 (0.57–0.96) | |

| CAS | 2339 | 78 | 33.3 | ||

| Sedation | |||||

| Antihistamines | 5480 | 24 | 4.4 | 1.05 (0.46–2.38) | |

| CAS | 2366 | 8 | 3.4 | ||

| Hypotension | |||||

| Antihistamines | 5464 | 63 | 11.5 | 0.65 (0.36–1.17) | |

| CAS | 2368 | 14 | 5.9 | ||

| aHR: age, sex adjusted. | |||||

| (a) Duration of use | |||

| CAS vs. Megestrol | CAS vs. Other Antihistamines | ||

| Dizziness | |||

| Duration | <4 weeks | 1.78 (0.89–3.55) | 0.97 (0.55–1.70) |

| 4 weeks~1 year | 1.35 (0.86–2.11) | 0.79 (0.55–1.13) | |

| ≥1 year | 0.38 (0.19–0.76) | 0.61 (0.41–0.92) | |

| Sedation | |||

| Duration | <4 weeks | 0.75 (0.10–5.91) | 1.00 (0.13–7.59) |

| 4 weeks~1 year | 0.75 (0.21–2.63) | 0.89 (0.27–2.98) | |

| ≥1 year | 0.22 (0.03–1.55) | 1.28 (0.38–4.32) | |

| Hypotension | |||

| Duration | <4 weeks | 1.47 (0.32–6.67) | 0.79 (0.19–3.27) |

| 4 weeks~1 year | 1.08 (0.50–2.34) | 0.94 (0.47–1.91) | |

| ≥1 year | 0.05 (0.01–0.49) | 0.29 (0.09–0.97) | |

| CAS; cyproheptadine-based appetite stimulant | |||

| (b) Age | |||

| CAS vs. Megestrol | CAS vs. Other Antihistamines | ||

| Dizziness | |||

| Age | ≥65 years old | 1.22 (0.80–1.86) | 0.80 (0.61–1.05) |

| <65 years old | 1.02 (0.70–1.50) | 0.38 (0.16–0.90) | |

| Sedation | |||

| Age | ≥65 years old | 0.59 (0.20–1.79) | 1.14 (0.49–2.64) |

| <65 years old | 0.53 (0.19–1.54) | - | |

| Hypotension | |||

| Age | ≥65 years old | 0.72 (0.34–1.52) | 0.77 (0.42–1.42) |

| <65 years old | 0.70 (0.34–1.44) | - | |

| CAS; cyproheptadine-based appetite stimulant | |||

| (c) Sex | |||

| CAS vs. Megestrol | CAS vs. Other Antihistamines | ||

| Dizziness | |||

| Sex | Female | 1.12 (0.47–2.52) | 0.52 (0.28–0.91) |

| Sedation | |||

| Sex | Female | 0.69 (0.14–2.58) | 0.83 (0.22–2.30) |

| Hypotension | |||

| Sex | Female | 0.78 (0.19–2.17) | 0.58 (0.23–1.36) |

| CAS; cyproheptadine-based appetite stimulant | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ko, M.; Kim, K.; Jang, H.; Lee, S.; Shin, B.; Cho, B.; Kim, S.; Jang, H.Y. Real-World Safety of Cyproheptadine-Based Appetite Stimulants: An Electronic Health Record-Based Retrospective Cohort Study in Adult Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010054

Ko M, Kim K, Jang H, Lee S, Shin B, Cho B, Kim S, Jang HY. Real-World Safety of Cyproheptadine-Based Appetite Stimulants: An Electronic Health Record-Based Retrospective Cohort Study in Adult Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleKo, Minoh, Kwangsoo Kim, Heeman Jang, Soomin Lee, Bumkyu Shin, Belong Cho, Seungyeon Kim, and Ha Young Jang. 2026. "Real-World Safety of Cyproheptadine-Based Appetite Stimulants: An Electronic Health Record-Based Retrospective Cohort Study in Adult Patients" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010054

APA StyleKo, M., Kim, K., Jang, H., Lee, S., Shin, B., Cho, B., Kim, S., & Jang, H. Y. (2026). Real-World Safety of Cyproheptadine-Based Appetite Stimulants: An Electronic Health Record-Based Retrospective Cohort Study in Adult Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010054