Inflammatory–Molecular Clusters as Predictors of Immunotherapy Response in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Patient Selection

2.3. Data Collection

- Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) = neutrophils/lymphocytes;

- Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) = platelets/lymphocytes;

- Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio (LMR) = lymphocytes/monocytes;

- Systemic Immune–Inflammation Index (SII) = (neutrophils × platelets)/lymphocytes.

2.4. Treatment and Follow-Up

Immunotherapy Regimens

2.5. Outcomes

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Baseline Inflammatory Indices

3.3. Inflammatory–Molecular Clusters

3.4. Response to Immunotherapy

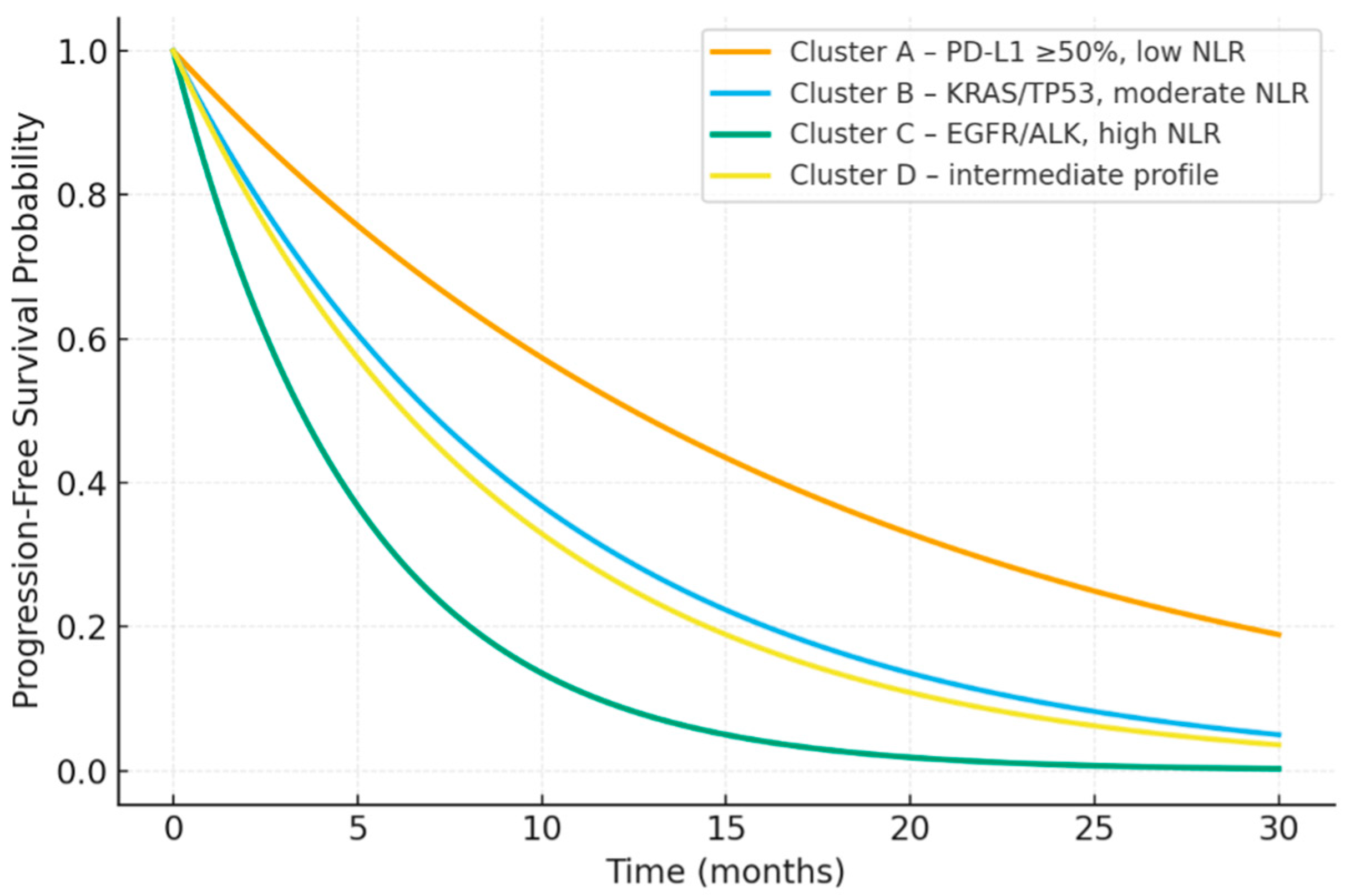

3.5. Survival Outcomes

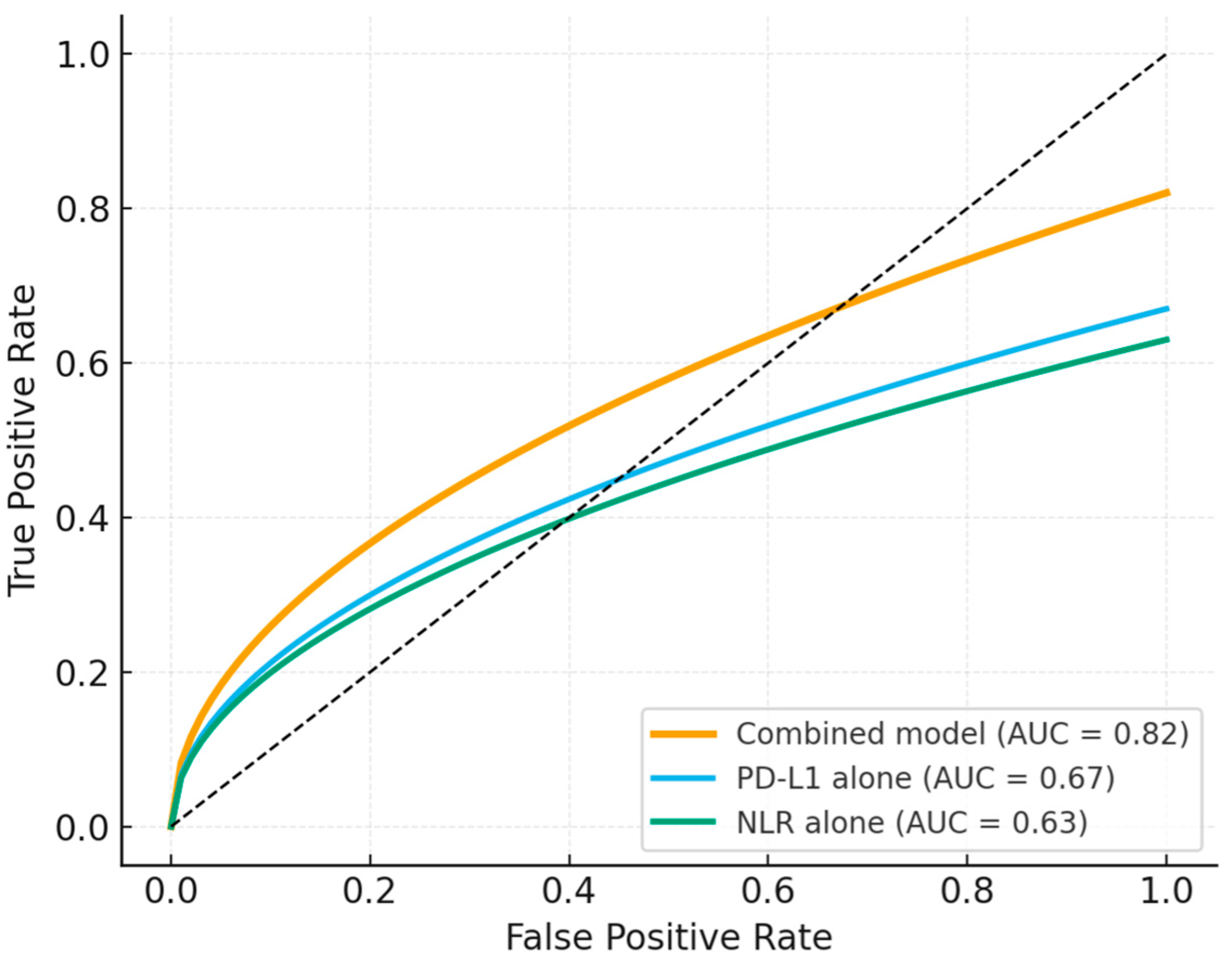

3.6. Predictive Model Performance

4. Discussion

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Russano, M.; La Cava, G.; Cortellini, A.; Citarella, F.; Galletti, A.; Di Fazio, G.R.; Santo, V.; Brunetti, L.; Vendittelli, A.; Fioroni, I.; et al. Immunotherapy for Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Therapeutic Advances and Biomarkers. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 2366–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, H.; Niu, X.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, S.; Fan, R.; Xiao, H.; Hu, S.S. Immunotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer: From mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Basumallik, N.; Agarwal, M. Small Cell Lung Cancer. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clark, S.B.; Alsubait, S. Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Incorvaia, L.; Fanale, D.; Badalamenti, G.; Barraco, N.; Bono, M.; Corsini, L.R.; Galvano, A.; Gristina, V.; Listì, A.; Vieni, S.; et al. Programmed Death Ligand 1 (PD-L1) as a Predictive Biomarker for Pembrolizumab Therapy in Patients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). Adv. Ther. 2019, 36, 2600–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, H.; Kim, R.; Jo, H.; Kim, H.R.; Hong, J.; Ha, S.Y.; Park, J.O.; Kim, S.T. Expression of PD-L1 as a predictive marker of sensitivity to immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2022, 15, 17562848221117638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, T.; Denman, D.; Bacot, S.M.; Feldman, G.M. Challenges and the Evolving Landscape of Assessing Blood-Based PD-L1 Expression as a Biomarker for Anti-PD-(L)1 Immunotherapy. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vitale, M.; Pagliaro, R.; Viscardi, G.; Pastore, L.; Castaldo, G.; Perrotta, F.; Campbell, S.F.; Bianco, A.; Scialò, F. Unraveling Resistance in Lung Cancer Immunotherapy: Clinical Milestones, Mechanistic Insights, and Future Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariean, C.R.; Tiuca, O.M.; Mariean, A.; Cotoi, O.S. Variation in CBC-Derived Inflammatory Biomarkers Across Histologic Subtypes of Lung Cancer: Can Histology Guide Clinical Management? Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, N.; Mao, J.; Tao, P.; Chi, H.; Jia, W.; Dong, C. The relationship between NLR/PLR/LMR levels and survival prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Medicine 2022, 101, e28617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khusnurrokhman, G.; Wati, F.F. Tumor-promoting inflammation in lung cancer: A literature review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 79, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alsaed, B.; Bobik, N.; Laitinen, H.; Nandikonda, T.; Ilonen, I.; Haikala, H.M. Shaping the battlefield: EGFR and KRAS tumor mutations’ role on the immune microenvironment and immunotherapy responses in lung cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2025, 44, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tian, L.; Li, H.; Cui, H.; Tang, C.; Zhao, P.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Y. Oncogenic KRAS mutations drive immune suppression through immune-related regulatory network and metabolic reprogramming. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Omer, H.A.; Janson, C.; Amin, K. The role of inflammatory and remodelling biomarkers in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2023, 48, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bai, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Bai, Y.; Chen, Q.; Bi, S.; Chen, S.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, F.; et al. Combined laboratory and imaging indicators to construct risk models for predicting immunotherapy efficacy and prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer: An observational study (STROBE compliant). Medicine 2025, 104, e45224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Knox, M.C.; Aryamanesh, N.; Marshall, L.L.; Varikatt, W.; Weerasinghe, C.; Burke, L.; Hau, E.; Nagrial, A.; Ashworth, S.; Kamran, S.C.; et al. Genomic and demographic landscape of non-small cell lung cancer within an ethnically-diverse population—The implications for radiation oncology and personalised medicine. R. Coll. Radiol. Open 2025, 3, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.D.; Jin, C.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.; Zhang, G.L.; Wang, C.G. Spontaneous histological transformation of lung squamous-cell carcinoma to large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and small cell lung cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 11333–11337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lababede, O.; Meziane, M.A. The Eighth Edition of TNM Staging of Lung Cancer: Reference Chart and Diagrams. Oncologist 2018, 23, 844–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jung, S.G.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, K.J.; Yang, I. Tumor response assessment by the single-lesion measurement per organ in small cell lung cancer. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2016, 28, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, C. Relationship between systemic immune-inflammation index and all-cause mortality in stages IIIB-IV epidermal growth factor receptor-mutated lung adenocarcinoma. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1698317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yuan, L.; Wang, Q.; Sun, F.; Shi, H. Deep learning and inflammatory markers predict early response to immunotherapy in unresectable NSCLC: A multicenter study. Biomol. Biomed. 2025, 25, 2252–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Yan, X.; Song, Q.; Wang, G.; Chen, R.; Jiao, S.; Wang, J. Pretreatment Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) May Predict the Outcomes of Advanced Non-small-cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs). Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vornicu, V.N.; Negru, A.G.; Vonica, R.C.; Cosma, A.A.; Saftescu, S.; Pasca-Fenesan, M.M.; Cimpean, A.M. Site-Specific Inflammatory Signatures in Metastatic NSCLC: Insights from Routine Blood Count Parameters. Medicina 2025, 61, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gainor, J.F.; Shaw, A.T.; Sequist, L.V.; Fu, X.; Azzoli, C.G.; Piotrowska, Z.; Huynh, T.G.; Zhao, L.; Fulton, L.; Schultz, K.R.; et al. EGFR Mutations and ALK Rearrangements Are Associated with Low Response Rates to PD-1 Pathway Blockade in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4585–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hastings, K.; Yu, H.A.; Wei, W.; Sanchez-Vega, F.; DeVeaux, M.; Choi, J.; Rizvi, H.; Lisberg, A.; Truini, A.; Lydon, C.A.; et al. EGFR mutation subtypes and response to immune checkpoint blockade treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gu, Y.; He, H.; Qiao, S.; Shao, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, F. EGFR: New Insights on Its Activation and Mutation in Tumor and Tumor Immunotherapy. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e05785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Foffano, L.; Bertoli, E.; Bortolot, M.; Torresan, S.; De Carlo, E.; Stanzione, B.; Del Conte, A.; Puglisi, F.; Spina, M.; Bearz, A. Immunotherapy in Oncogene-Addicted NSCLC: Evidence and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Wang, P.; Zheng, S.; Lei, Z.; Xu, W.; Wang, Y.; Pan, X.; Feng, Q.; Yang, J. KRAS mutations promote PD-L1-mediated immune escape by ETV4 in lung adenocarcinoma. Transl. Oncol. 2025, 61, 102525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Skoulidis, F.; Heymach, J.V. Co-occurring genomic alterations in non-small-cell lung cancer biology and therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Budczies, J.; Romanovsky, E.; Kirchner, M.; Neumann, O.; Blasi, M.; Schnorbach, J.; Shah, R.; Bozorgmehr, F.; Savai, R.; Stiewe, T.; et al. KRAS and TP53 co-mutation predicts benefit of immune checkpoint blockade in lung adenocarcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sumii, M.; Namba, M.; Tokumo, K.; Yamauchi, M.; Okamoto, W.; Hattori, N.; Sugiyama, K. Concurrent Mutations in STK11 and KEAP1 Cause Treatment Resistance in KRAS Wild-type Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. Intern. Med. 2023, 62, 3001–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alagoz, A.N.; Dagdas, A.; Bunul, S.D.; Erci, G.C. The Relationship Between Systemic Inflammatory Index and Other Inflammatory Markers with Clinical Severity of the Disease in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dragani, T.A.; Muley, T.; Schneider, M.A.; Kobinger, S.; Eichhorn, M.; Winter, H.; Hoffmann, H.; Kriegsmann, M.; Noci, S.; Incarbone, M.; et al. Lung Adenocarcinoma Diagnosed at a Younger Age Is Associated with Advanced Stage, Female Sex, and Ever-Smoker Status, in Patients Treated with Lung Resection. Cancers 2023, 15, 2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Scheel, A.H.; Ansén, S.; Schultheis, A.M.; Scheffler, M.; Fischer, R.N.; Michels, S.; Hellmich, M.; George, J.; Zander, T.; Brockmann, M.; et al. PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer: Correlations with genetic alterations. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1131379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, H.J.; Cha, Y.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, A.; Kim, E.Y.; Chang, Y.S. Keratinization of Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma Is Associated with Poor Clinical Outcome. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2017, 80, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hao, Z.; Lin, M.; Du, F.; Xin, Z.; Wu, D.; Yu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; et al. Systemic Immune Dysregulation Correlates With Clinical Features of Early Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 754138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rajasegaran, T.; How, C.W.; Saud, A.; Ali, A.; Lim, J.C.W. Targeting Inflammation in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer through Drug Repurposing. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tamminga, M.; Hiltermann, T.J.N.; Schuuring, E.; Timens, W.; Fehrmann, R.S.; Groen, H.J. Immune microenvironment composition in non-small cell lung cancer and its association with survival. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2020, 9, e1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mosca, M.; Nigro, M.C.; Pagani, R.; De Giglio, A.; Di Federico, A. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) in NSCLC, Gastrointestinal, and Other Solid Tumors: Immunotherapy and Beyond. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Naqash, A.R.; Floudas, C.S.; Aber, E.; Maoz, A.; Nassar, A.H.; Adib, E.; Choucair, K.; Xiu, J.; Baca, Y.; Ricciuti, B.; et al. Influence of TP53Comutation on the Tumor Immune Microenvironment and Clinical Outcomes With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in STK11-Mutant Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, e2300371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, X.; Luo, B.; Tian, J.; Wang, Y.; Lu, X.; Ni, J.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Ren, S. Biomarkers and ImmuneScores in lung cancer: Predictive insights for immunotherapy and combination treatment strategies. Biol. Proced. Online 2025, 27, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ji, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, X.D.; Zhao, W.Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, J.T.; Wu, C.P. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in non-small-cell lung cancer and its relation with EGFR mutation. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tsai, Y.T.; Schlom, J.; Donahue, R.N. Blood-based biomarkers in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint blockade. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, A.M.; Everaert, C.; Van Damme, E.; De Preter, K.; Vermaelen, K. Circulating Immune Cell Dynamics as Outcome Predictors in Lung Cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e007023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronte, V.; Brandau, S.; Chen, S.H.; Colombo, M.P.; Frey, A.B.; Greten, T.F.; Mandruzzato, S.; Murray, P.J.; Ochoa, A.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; et al. Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrilovich, D.I. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017, 5, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, W.; Pagès, F.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Galon, J. The immune contexture in human tumours: Impact on clinical outcome. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placke, T.; Örgel, M.; Schaller, M.; Jung, G.; Rammensee, H.G.; Kopp, H.G.; Salih, H.R. Platelet-derived MHC class I confers a pseudonormal phenotype to cancer cells that subverts the antitumor reactivity of natural killer immune cells. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labelle, M.; Begum, S.; Hynes, R.O. Platelets Guide the Formation of Early Metastatic Niches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E3053–E3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezquita, L.; Auclin, E.; Ferrara, R.; Charrier, M.; Remon, J.; Planchard, D.; Ponce, S.; Ares, L.P.; Leroy, L.; Audigier-Valette, C.; et al. Association of the Lung Immune Prognostic Index With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Outcomes in Patients With Advanced NSCLC. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart, J.; Chen, E.; Prasad, V. Estimation of the Percentage of Patients With Cancer Who Benefit From Genome-Driven Oncology. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalian, S.; Taube, J.; Anders, R.; Pardoll, D.M. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Nathanson, T.; Rizvi, H.; Creelan, B.C.; Sanchez-Vega, F.; Ahuja, A.; Ni, A.; Novik, J.B.; Mangarin, L.M.; Abu-Akeel, M.; et al. Genomic Features of Response to Combination Immunotherapy in Patients With Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 843–852.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsson, V.; Gibbs, D.L.; Brown, S.D.; Wolf, D.; Bortone, D.S.; Ou Yang, T.-H.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Gao, G.F.; Plaisier, C.L.; Eddy, J.A.; et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity 2018, 48, 812–830.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, P.S.; Karanikas, V.; Evers, S. The Where, the When, and the How of Immune Monitoring for Cancer Immunotherapies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1865–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariathasan, S.; Turley, S.J.; Nickles, D.; Castiglioni, A.; Yuen, K.; Wang, Y.; Kadel, E.E., III; Koeppen, H.; Astarita, J.L.; Cubas, R.; et al. TGFβ Attenuates Tumour Response to PD-L1 Blockade by Contributing to Exclusion of T Cells. Nature 2018, 554, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumeh, P.C.; Harview, C.L.; Yearley, J.H.; Shintaku, I.P.; Taylor, E.J.M.; Robert, L.; Chmielowski, B.; Spasic, M.; Henry, G.; Ciobanu, V.; et al. PD-1 Blockade Induces Responses by Inhibiting Adaptive Immune Resistance. Nature 2014, 515, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranger, S.; Bao, R.; Gajewski, T.F. Melanoma-Intrinsic β-Catenin Signaling Prevents Anti-Tumour Immunity. Nature 2015, 523, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; Chan, V.; Fearon, D.F.; Merad, M.; Coussens, L.M.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Hedrick, C.C.; et al. Understanding the Tumor Immune Microenvironment (TIME) for Effective Therapy. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zappasodi, R.; Merghoub, T.; Wolchok, J.D. Emerging Concepts for Immune Checkpoint Blockade-Based Combination Therapies. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic & Stage |

| |

| Treatment |

|

|

| Baseline Laboratory Data |

|

|

| Autoimmune/Inflammatory Conditions |

|

|

| Molecular/IHC Data |

|

|

| Clinical Data & Follow-up |

|

|

| Data Quality |

|

|

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 65.1 ± 9.5 |

| Sex, n (%) | Male: 210 (70.5%) Female: 88 (29.5%) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | Current/former: 214 (71.8%) Never: 84 (28.2%) |

| ECOG performance status 0–1, n (%) | 189 (63.4%) |

| Histology, n (%) | Adenocarcinoma: 163 (54.7%) Squamous: 93 (31.2%) Large cell: 42 (14.1%) |

| Primary tumor location | Peripheral: 182 (61.1%) Central: 116 (38.9%) |

| PD-L1 expression, n (%) | <1%: 79 (26.5%) 1–49%: 111 (37.2%) ≥50%: 108 (36.3%) |

| EGFR mutation | 14 (4.7%) |

| KRAS mutation | 8 (2.7%) |

| ALK rearrangement | 3 (1.0%) |

| TP53 alteration | 39 (13.1%) |

| Comorbidities (≥1 major) | 168 (56.4%) |

| Inflammatory Marker | PD-L1 < 1% (n = 79) | PD-L1 1–49% (n = 111) | PD-L1 ≥ 50% (n = 108) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLR, IQR | 6.0 (3.8–8.5) | 5.0 (3.2–6.9) | 3.8 (2.5–5.8) | 0.018 |

| PLR, IQR | 255 (206–310) | 243 (191–285) | 218 (168–267) | 0.032 |

| LMR, IQR | 2.0 (1.6–2.5) | 2.3 (1.7–2.8) | 2.8 (2.1–3.4) | 0.011 |

| SII, IQR | 1180 (860–1650) | 1020 (750–1340) | 880 (670–1150) | 0.024 |

| Cluster | PD-L1 Profile | Dominant Molecular Alterations | Median NLR | Median LMR | Patients (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | ≥50% | Wild type | 2.4 | 3.0 | 78 (26.2%) |

| B | 1–49% | KRAS, TP53 | 6.0 | 2.1 | 71 (23.8%) |

| C | <1% | EGFR, ALK | 6.8 | 1.8 | 59 (19.8%) |

| D | Mixed | None detected | 4.2 | 2.6 | 90 (30.2%) |

| Cluster | (ORR, %) | (DCR, %) | Median PFS (Months) | Median OS (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 41.0 | 77.0 | 13.0 | 22.5 |

| B | 25.3 | 55.6 | 8.4 | 15.9 |

| C | 7.0 | 26.5 | 4.3 | 9.2 |

| D | 26.7 | 50.0 | 9.1 | 14.8 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (HR) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| NLR ≥ 5 | 2.12 | 1.46–3.07 | <0.001 |

| PD-L1 < 1% | 1.91 | 1.26–2.90 | 0.002 |

| EGFR mutation | 2.36 | 1.28–4.36 | 0.006 |

| KRAS mutation | 1.59 | 0.89–2.83 | 0.108 |

| TP53 alteration | 1.22 | 0.78–1.90 | 0.373 |

| ECOG ≥ 2 | 1.64 | 1.05–2.57 | 0.028 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vornicu, V.; Negru, A.-G.; Vonica, R.C.; Cosma, A.A.; Pasca-Fenesan, M.M.; Cimpean, A.M. Inflammatory–Molecular Clusters as Predictors of Immunotherapy Response in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010349

Vornicu V, Negru A-G, Vonica RC, Cosma AA, Pasca-Fenesan MM, Cimpean AM. Inflammatory–Molecular Clusters as Predictors of Immunotherapy Response in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):349. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010349

Chicago/Turabian StyleVornicu, Vlad, Alina-Gabriela Negru, Razvan Constantin Vonica, Andrei Alexandru Cosma, Mihaela Maria Pasca-Fenesan, and Anca Maria Cimpean. 2026. "Inflammatory–Molecular Clusters as Predictors of Immunotherapy Response in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010349

APA StyleVornicu, V., Negru, A.-G., Vonica, R. C., Cosma, A. A., Pasca-Fenesan, M. M., & Cimpean, A. M. (2026). Inflammatory–Molecular Clusters as Predictors of Immunotherapy Response in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010349