Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Non-ICU Hospitalized Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Primary and Secondary Outcomes

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Population: studies in which the majority of participants had T2DM, or stress hyperglycemia (with or without previously known diabetes). This variability was recorded during data extraction and considered a potential source of clinical heterogeneity. Studies including a small proportion (<10%) of patients with type 1 diabetes (T1DM) were accepted if results were not stratified, and the population was predominantly T2DM.

- Setting and intervention: studies conducted in non-ICU hospital environments in which CGM was used during at least part of the admission. Eligible populations included post-operative inpatients, individuals transferred from ICU to non-ICU wards before CGM initiation, patients receiving glucocorticoids, those scheduled for elective procedures, and those receiving artificial nutrition. Use of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) during admission was acceptable, provided this use was restricted to the inpatient setting and not part of long-term outpatient pump therapy.

- Outcomes: studies that reported standard CGM-derived glycemic metrics relevant to inpatient monitoring (e.g., TIR, TAR, TBR, MG, or GV), in alignment with the objectives of this review.

- Study design: only RCTs providing a direct comparison between CGM and capillary POC glucose testing.

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Studies involving exclusively adults with T1DM, pediatric patients, gestational diabetes, adults undergoing dialysis, adults admitted to ICU, and patients undergoing continuous intravenous insulin infusions.

- Studies not involving hospitalized patients.

- Studies that did not evaluate patients under insulin treatment, since inpatient glycemic protocols rely on scheduled insulin therapy and the effect of CGM cannot be meaningfully assessed in the absence of insulin-based management.

- Studies using hybrid closed-loop systems.

- Unpublished reports.

- Animal or in vitro studies.

2.4. Data Collection and Quality Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Risk of Bias

3.3. Baseline Characteristics of Included Studies

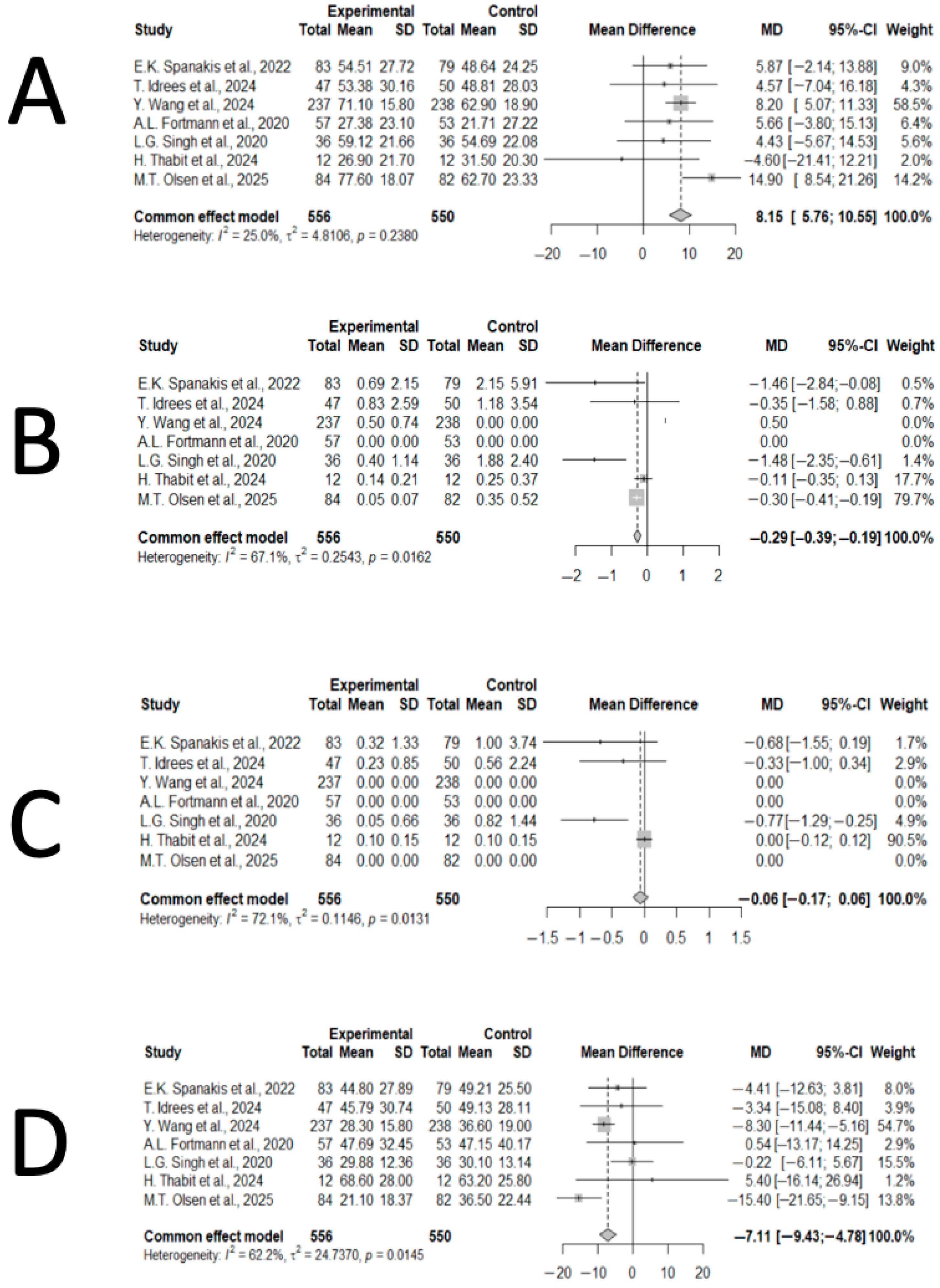

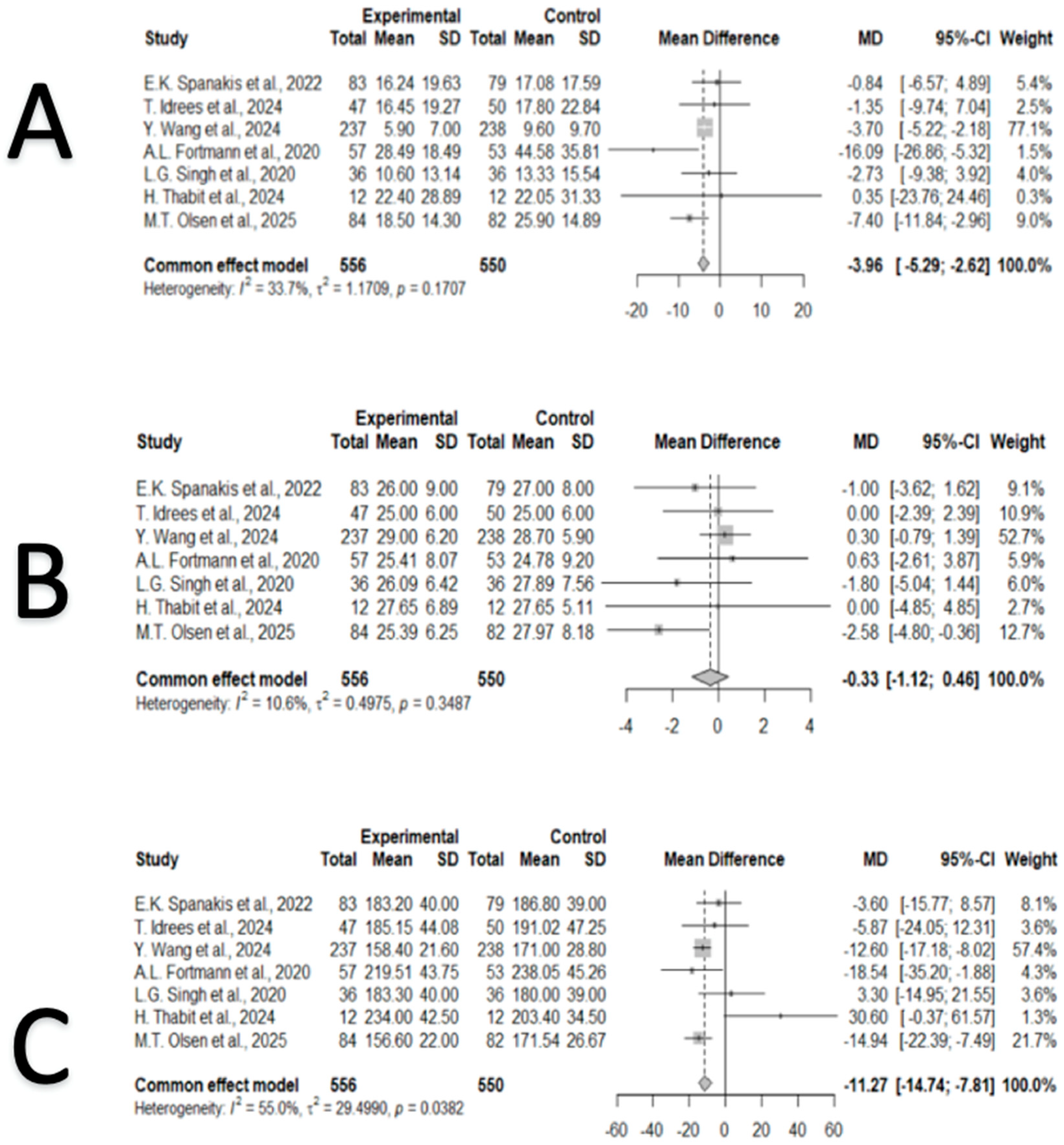

3.4. Synthesis of Results

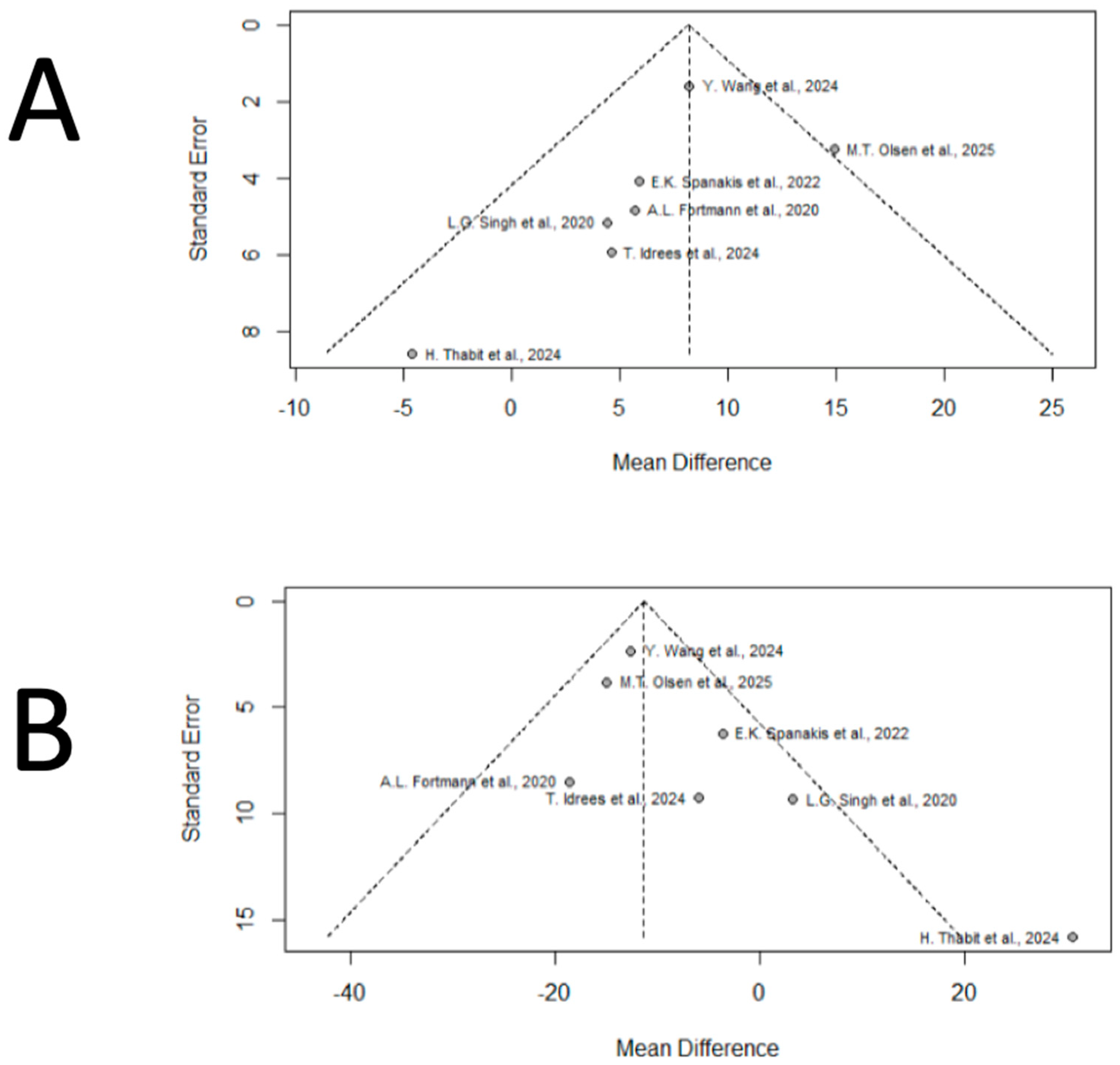

3.5. Publication Bias

3.6. Consistency

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Comparison with Previous Literature

4.3. Mechanistic Interpretation

4.4. Future Directions

4.5. Sources of Bias and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dhatariya, K.; Corsino, L.; Umpierrez, G.E. Management of Diabetes and Hyperglycemia in Hospitalized Patients. 2000. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279093/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Kufeldt, J.; Kovarova, M.; Adolph, M.; Staiger, H.; Bamberg, M.; Häring, H.U.; Fritsche, A.; Peter, A. Prevalence and Distribution of Diabetes Mellitus in a Maximum Care Hospital: Urgent Need for HbA1c-Screening. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2018, 126, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.B.; Kongable, G.L.; Potter, D.J.; Abad, V.J.; Leija, D.E.; Anderson, M. Inpatient glucose control: A glycemic survey of 126 U.S. hospitals. J. Hosp. Med. 2009, 4, E7–E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umpierrez, G.E.; Isaacs, S.D.; Bazargan, N.; You, X.; Thaler, L.M.; Kitabchi, A.E. Hyperglycemia: An Independent Marker of In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with Undiagnosed Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olariu, E.; Pooley, N.; Danel, A.; Miret, M.; Preiser, J.C. A systematic scoping review on the consequences of stress-related hyperglycaemia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umpierrez, G.E.; Hellman, R.; Korytkowski, M.T.; Kosiborod, M.; Maynard, G.A.; Montori, V.M.; Seley, J.J.; Van den Berghe, G. Management of Hyperglycemia in Hospitalized Patients in Non-Critical Care Setting: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berghe, G.; Wouters, P.; Weekers, F.; Verwaest, C.; Bruyninckx, F.; Schetz, M.; Vlasselaers, D.; Ferdinande, P.; Lauwers, P.; Bouillon, R. Intensive Insulin Therapy in Critically Ill Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1359–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falciglia, M.; Freyberg, R.W.; Almenoff, P.L.; D’Alessio, D.A.; Render, M.L. Hyperglycemia–related mortality in critically ill patients varies with admission diagnosis*. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, 3001–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 16. Diabetes Care in the Hospital: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, S321–S334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquel, F.J.; Fayfman, M.; Umpierrez, G.E. Debate on Insulin vs Non-insulin Use in the Hospital Setting—Is It Time to Revise the Guidelines for the Management of Inpatient Diabetes? Curr. Diab. Rep. 2019, 19, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Nieves, M.; Juneja, R.; Fan, L.; Meadows, E.; Lage, M.J.; Eby, E.L. Trends in U.S. Insulin Use and Glucose Monitoring for People with Diabetes: 2009–2018. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2022, 16, 1428–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonde, L.; Umpierrez, G.E.; Reddy, S.S.; McGill, J.B.; Berga, S.L.; Bush, M.; Chandrasekaran, S.; DeFronzo, R.A.; Einhorn, D.; Galindo, R.J.; et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: Developing a Diabetes Mellitus Comprehensive Care Plan—2022 Update. Endocr. Pract. 2022, 28, 923–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesco, A.T.; Jedraszko, A.M.; Garza, K.P.; Weissberg-Benchell, J. Continuous Glucose Monitoring Associated with Less Diabetes-Specific Emotional Distress and Lower A1c Among Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2018, 12, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokkert, M.J.; Damman, A.; Van Dijk, P.R.; Edens, M.A.; Abbes, S.; Braakman, J.; Slingerland, R.J.; Dikkeschei, L.D.; Dille, J.; Bilo, H.J.G. Use of FreeStyle Libre Flash Monitor Register in the Netherlands (FLARE-NL1): Patient Experiences, Satisfaction, and Cost Analysis. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 2019, 4649303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergenstal, R.M.; Martens, T.W.; Beck, R.W. Continuous Glucose Monitoring. JAMA 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seisa, M.O.; Saadi, S.; Nayfeh, T.; Muthusamy, K.; Shah, S.H.; Firwana, M.; Hasan, B.; Jawaid, T.; Abd-Rabu, R.; Korytkowski, M.T.; et al. A Systematic Review Supporting the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Hyperglycemia in Adults Hospitalized for Noncritical Illness or Undergoing Elective Surgical Procedures. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. Endocr. Soc. 2022, 107, 2139–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, G.; Zhang, X.; Ye, Y.; Wang, C.; Hu, L.; Wu, H.; Qiu, Z.; Yuan, F.; Chen, J.; Lai, S. Cost-Effectiveness of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Chinese Adults with Uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes: A Modelling Study Stratified by Baseline HbA1c. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Ilham, S.; Alshannaq, H.; Pollock, R.F.; Field, M.; Norman, G.J.; Jin, S.M.; Kim, J.H. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Real-Time Continuous Glucose Monitoring Versus Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose in People with Type 2 Diabetes Treated with Non-Intensive Insulin Therapy in South Korea. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Allows Expanded Use of Devices to Monitor Patients’ Vital Signs Remotely. 2020. Available online: https://www.biospace.com/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-allows-expanded-use-of-devices-to-monitor-patients-vital-signs-remotely?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Singh, L.G.; Satyarengga, M.; Marcano, I.; Scott, W.H.; Pinault, L.F.; Feng, Z.; Sorkin, J.D.; Umpierrez, G.E.; Spanakis, E.K. Reducing inpatient hypoglycemia in the general wards using real-time continuous glucose monitoring: The glucose telemetry system, a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 2736–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, T.; Castro-Revoredo, I.A.; Oh, H.D.; Gavaller, M.D.; Zabala, Z.; Moreno, E.; Moazzami, B.; Galindo, R.J.; Vellanki, P.; Cabb, E.; et al. Continuous Glucose Monitoring-Guided Insulin Administration in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2024, 25, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortmann, A.L.; Bagsic, S.R.S.; Talavera, L.; Garcia, I.M.; Sandoval, H.; Hottinger, A.; Philis-Tsimikas, A. Glucose as the fifth vital sign: A randomized controlled trial of continuous glucose monitoring in a non-ICU hospital setting. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 2873–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanakis, E.K.; Urrutia, A.; Galindo, R.J.; Vellanki, P.; Migdal, A.L.; Davis, G.; Fayfman, M.; Idrees, T.; Pasquel, F.J.; Coronado, W.Z.; et al. Continuous Glucose Monitoring–Guided Insulin Administration in Hospitalized Patients With Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 2369–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Wang, M.; Ni, J.; Yu, J.; Wang, S.; Wu, L.; Lu, W.; Zhu, W.; Guo, J.; et al. Real-time continuous glucose monitoring-guided glucose management in inpatients with diabetes receiving short-term continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion: A randomized clinical trial. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2024, 48, 101067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.T.; Klarskov, C.K.; Jensen, S.H.; Rasmussen, L.M.; Lindegaard, B.; Andersen, J.A.; Gottlieb, H.; Lunding, S.; Pedersen-Bjergaard, U.; Hansen, K.B.; et al. In-Hospital Diabetes Management by a Diabetes Team and Insulin Titration Algorithms Based on Continuous Glucose Monitoring or Point-of-Care Glucose Testing in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (DIATEC): A Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabit, H.; Rubio, J.; Karuppan, M.; Mubita, W.; Lim, J.; Thomas, T.; Fonseca, I.; Fullwood, C.; Leelarathna, L.; Schofield, J. Use of real-time continuous glucose monitoring in non-critical care insulin-treated inpatients under non-diabetes speciality teams in hospital: A pilot randomized controlled study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 5483–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W.; Bergenstal, R.M.; Cheng, P.; Kollman, C.; Carlson, A.L.; Johnson, M.L.; Rodbard, D. The Relationships Between Time in Range, Hyperglycemia Metrics, and HbA1c. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2019, 13, 614–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigersky, R.A.; McMahon, C. The Relationship of Hemoglobin A1C to Time-in-Range in Patients with Diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2019, 21, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelino, T.; Danne, T.; Bergenstal, R.M.; Amiel, S.A.; Beck, R.; Biester, T.; Bosi, E.; Buckingham, B.A.; Cefalu, W.T.; Close, K.L.; et al. Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: Recommendations from the international consensus on time in range. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1593–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H.; Brożek, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. GRADE Handbook for Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, T.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Gemma, M.; Guérin, C.; Zangrillo, A.; Landoni, G. How to impute study-specific standard deviations in meta-analyses of skewed continuous endpoints? World J. Metaanal. 2015, 3, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Sutton, A.J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Terrin, N.; Jones, D.R.; Lau, J.; Carpenter, J.; Rücker, G.; Harbord, R.M.; Schmid, C.H.; et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Welch, V.; Flemyng, E. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Updated 2024; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2024; Available online: www.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- DexCom Inc. FDA Authorizes Marketing of the New Dexcom G6® CGM Eliminating Need for Fingerstick Blood Testing for People with Diabetes; DexCom Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dexcom Inc. Dexcom G6 Continuous Glucose Monitoring System. User Guide. 2022. Available online: https://www.dexcom.com/guides (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Garg, S.K.; Kipnes, M.; Castorino, K.; Bailey, T.S.; Akturk, H.K.; Welsh, J.B.; Christiansen, M.P.; Balo, A.K.; Brown, S.A.; Reid, J.L.; et al. Accuracy and Safety of Dexcom G7 Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Adults with Diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2022, 24, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, M.P.; Garg, S.K.; Brazg, R.; Bode, B.W.; Bailey, T.S.; Slover, R.H.; Sullivan, A.; Huang, S.; Shin, J.; Lee, S.W.; et al. Accuracy of a Fourth-Generation Subcutaneous Continuous Glucose Sensor. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2017, 19, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galindo, R.J.; Aleppo, G.; Klonoff, D.C.; Spanakis, E.K.; Agarwal, S.; Vellanki, P.; Olson, D.E.; Umpierrez, G.E.; Davis, G.M.; Pasquel, F.J.; et al. Implementation of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in the Hospital: Emergent Considerations for Remote Glucose Monitoring During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2020, 14, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, T.; Aaron, R.E.; Seley, J.J.; Longo, R.; Nayberg, I.; Umpierrez, G.E.; Levy, C.J.; Klonoff, D.C. Use of Continuous Glucose Monitors Upon Hospital Discharge of People with Diabetes: Promise, Barriers, and Opportunity. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2024, 18, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umpierrez, G.E.; Castro-Revoredo, I.; Moazzami, B.; Nayberg, I.; Zabala, Z.; Galindo, R.J.; Vellanki, P.; Peng, L.; Klonoff, D.C. Randomized Study Comparing Continuous Glucose Monitoring and Capillary Glucose Testing in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes After Hospital Discharge. Endocr. Pract. 2025, 31, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Group | Paients per Group | Overall Number of Patients | % Men | Mean Age (Years) (SD) | % T2DM | Sensor | % TIR (SD) | % TBR < 70 (SD) | % TBR < 55 (SD) | % TAR > 180 (SD) | % TAR > 250 (SD) | GV (CV) (SD) | MG (mg/dL) (SD) | Mean Hospitalized Time (Days) | 30-Day Readmissions IRR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fortmann et al. (2020) [22] | Active | 57 | 110 | 47.4 | 62.9 (14.0) | 100 | DEXCOM G6 | 27.4 (23.1) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 47.7 (32.5) | 28.5 (18.5) | 25.4 (8.1) | 219.5 (43.8) | 6 (4.4) | NA |

| Control | 53 | 43.4 | 60.9 (12.4) | 100 | 21.7 (27.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 47.2 (40.2) | 44.6 (35.8) | 24.8 (9.2) | 238.1 (45.3) | 5.5 (3.7) | ||||

| Singh et al. (2020) [20] | Active | 36 | 72 | 91.7 | 68 (9.0) | 100 | DEXCOM G6 | 59.1 (21.7) | 0.4 (1.1) | 0.1 (0.7) | 29.9 (12.4) | 10.6 (13.4) | 26.1 (6.4) | 183.3 (40.0) | NA | NA |

| Control | 36 | 94.4 | 68 (10.0) | 100 | 54.7 (22.1)) | 1.9 (2.4) | 0.8 (1.4) | 30.1 (13.1) | 13.3 (15.5) | 27.9 (7.6) | 180.0 (39.0) | |||||

| Spanakis et al. (2022) [23] | Active | 83 | 162 | 58 | 57.3 (12.3) | 88 | DEXCOM G6 | 54.5 (27.7) | 0.7 (2.1) | 0.3 (1.3) | 16.2 (19.6) | 16.2 (19.6) | 26.0 (9.0) | 183.2 (40.0) | NA | NA |

| Control | 79 | 63 | 55.1 (9.3) | 91 | 48.6 (24.3) | 2.2 (5.9) | 1.0 (3.7) | 17.1 (17.6) | 17.1 (17.6) | 27.0 (8.0) | 186.8 (39.0) | |||||

| Idrees et al. (2024) [21] | Active | 47 | 97 | 38 | 74.9 (11.7) | 100 | DEXCOM G6 | 53.4 (30.2) | 0.8 (2.6) | 0.2 (0.9) | 16.5 (19.3) | 16.2 (19.6) | 25.0 (6.0) | 185.2 (44.1) | 1.0 (12.4) | NA |

| Control | 50 | 28 | 74.5 (10.6) | 100 | 48.8 (28.0) | 1.2 (3.5) | 0.6 (2.2) | 17.8 (22.8) | 17.1 (17.6) | 25.0 (6.0) | 191.0 (47.3) | 1.5 (3) | ||||

| Wang et al. (2024) [24] | Active | 237 | 475 | 57 | 71.1 (15.8) | 89 | GUARDIAN SENSOR 3 | 71.1 (15.8) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 5.9 (7.0) | 5.9 (7.0) | 29.0 (6.2) | 158.4 (21.6) | 6.7 (0.8) | |

| Control | 238 | 63.4 | 62.9 (18.9) | 92 | 62.9 (18.9) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 9.6 (9.7) | 9.6 (9.7) | 28.7 (5.9) | 171.0 (28.8) | 6.7 (0.8) | NA | |||

| Thabit et al. (2024) [26] | Active | 12 | 24 | 76 | 62.1 (9.0) | 100 | DEXCOM G7 | 26.9 (21.7) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.2) | 22.4 (8.9) | 22.4 (28.9) | 27.7 (6.9) | 234.0 (42.5) | 6.5 (5.2) | NA |

| Control | 12 | 100 | 31.5 (20.3) | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.1 (0.2 | 22.1 (31.3) | 22.1 (31.3) | 27.7 (5.1) | 203.4 (34.5) | 7 (4.4) | ||||||

| Olsen et al. (2025) [25] | Active | 84 | 166 | 61.9 | 76.6 (9.5) | 100 | DEXCOM G6 | 77.6 (24.4) | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.0 (0.0) | 21.1 (24.8) | 1.3 (5.6) | 25.39 (6.25) | 8.7 (1.7) | 5.0 (5.0) | 0.88 (0.74–1.04) |

| Control | 82 | 65.9 | 75.5 (10.1) | 100 | 62.7 (31.5) | 0.0 (0.7) | 0.0 (0.0) | 36.5 (30.3) | 11.2 (16.1) | 27.97 (8.18) | 9.5 (2.0) | 5.0 (4.3) | 1.00 (Reference) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lara-Gálvez, D.; Rubio-Almanza, M.; Aparicio-Ródenas, Y.; Sanchis-Pascual, D.; Masdeu-López-Cerón, P.; Pérez-Cervantes, V.; Merino-Torres, J.F. Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Non-ICU Hospitalized Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010034

Lara-Gálvez D, Rubio-Almanza M, Aparicio-Ródenas Y, Sanchis-Pascual D, Masdeu-López-Cerón P, Pérez-Cervantes V, Merino-Torres JF. Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Non-ICU Hospitalized Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleLara-Gálvez, Darío, Matilde Rubio-Almanza, Yolanda Aparicio-Ródenas, David Sanchis-Pascual, Pilar Masdeu-López-Cerón, Victor Pérez-Cervantes, and Juan Francisco Merino-Torres. 2026. "Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Non-ICU Hospitalized Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010034

APA StyleLara-Gálvez, D., Rubio-Almanza, M., Aparicio-Ródenas, Y., Sanchis-Pascual, D., Masdeu-López-Cerón, P., Pérez-Cervantes, V., & Merino-Torres, J. F. (2026). Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Non-ICU Hospitalized Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010034