Cardiac CT in Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (NOCAD): A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

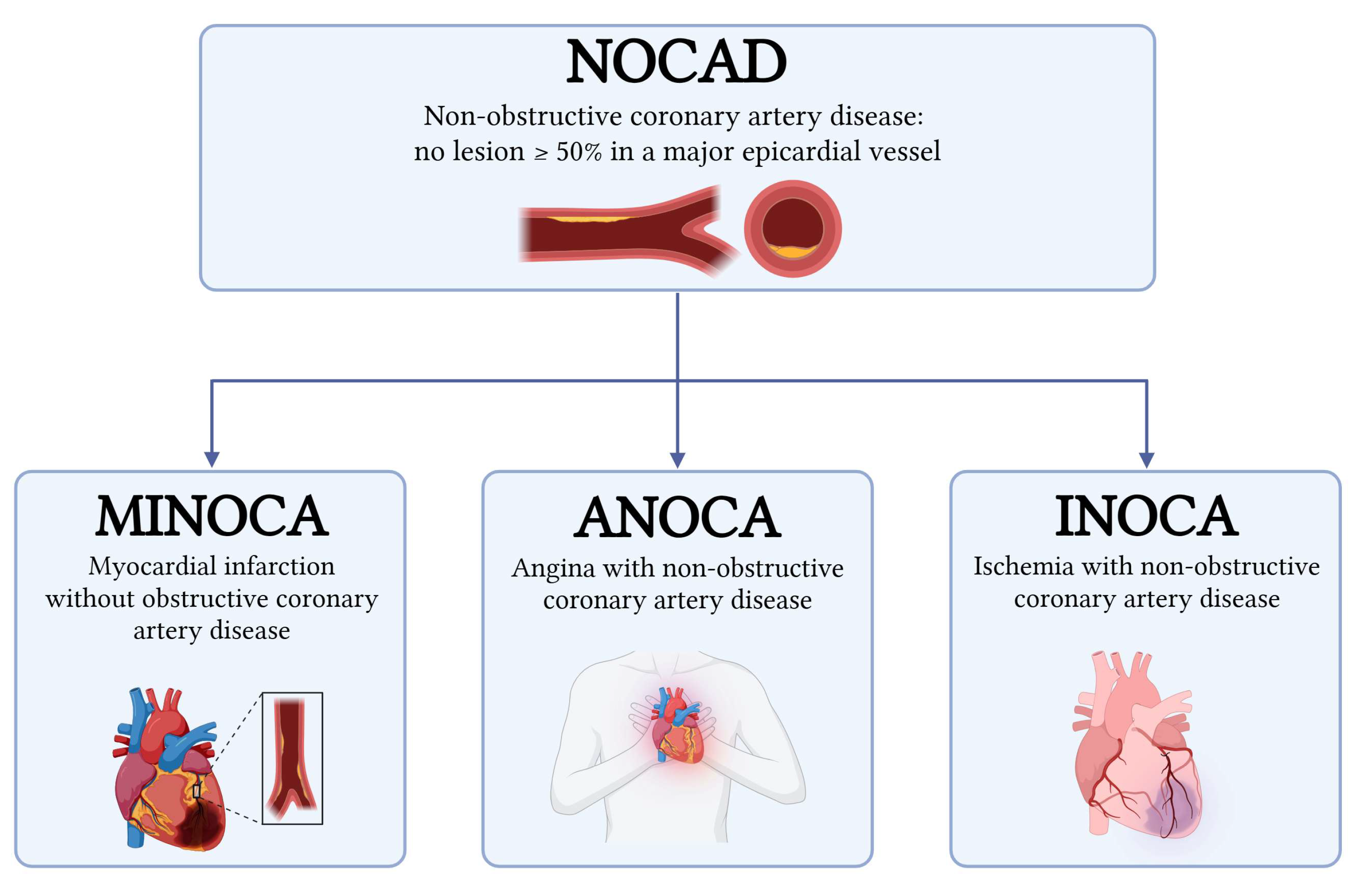

2. Definitions

- Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA) can be diagnosed if the criteria of the fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction are fulfilled and obstructive coronary artery disease is ruled out by coronary angiography (no lesion ≥ 50% in a major epicardial vessel) [6,7,8]. MINOCA accounts for approximately 6–15% of all myocardial infarctions and encompasses a wide range of mechanisms, including plaque disruption, coronary artery spasm, coronary dissection, coronary embolism, type 2 myocardial infarction (MI), and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy [7,9]. Traditionally regarded as a benign entity, MINOCA is now recognized to confer a significantly increased risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes compared with the general population [10,11].

- Angina with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (ANOCA) and Ischemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (INOCA): the difference between these two entities, although minimal, lies in their definition. ANOCA highlights the presence of anginal symptoms, while INOCA focuses on evidence of myocardial ischemia (such as abnormal stress testing or imaging) in the absence of obstructive CAD (<50% stenosis). The term ANOCA is generally used in cases of symptoms related to suspected myocardial ischemia that has not yet been identified or that could not be documented by instrumental imaging, while the term INOCA is used in the presence of documented ischemia, even in the absence of symptoms. Both conditions often share the same pathophysiological mechanisms, as the mismatch between blood supply and myocardial oxygen demands are primarily caused by coronary microvascular dysfunction, microvascular spasm, endothelial dysfunction, epicardial spasm, and myocardial bridging [1,2,3,12,13].

2.1. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of MINOCA

2.2. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of ANOCA/INOCA

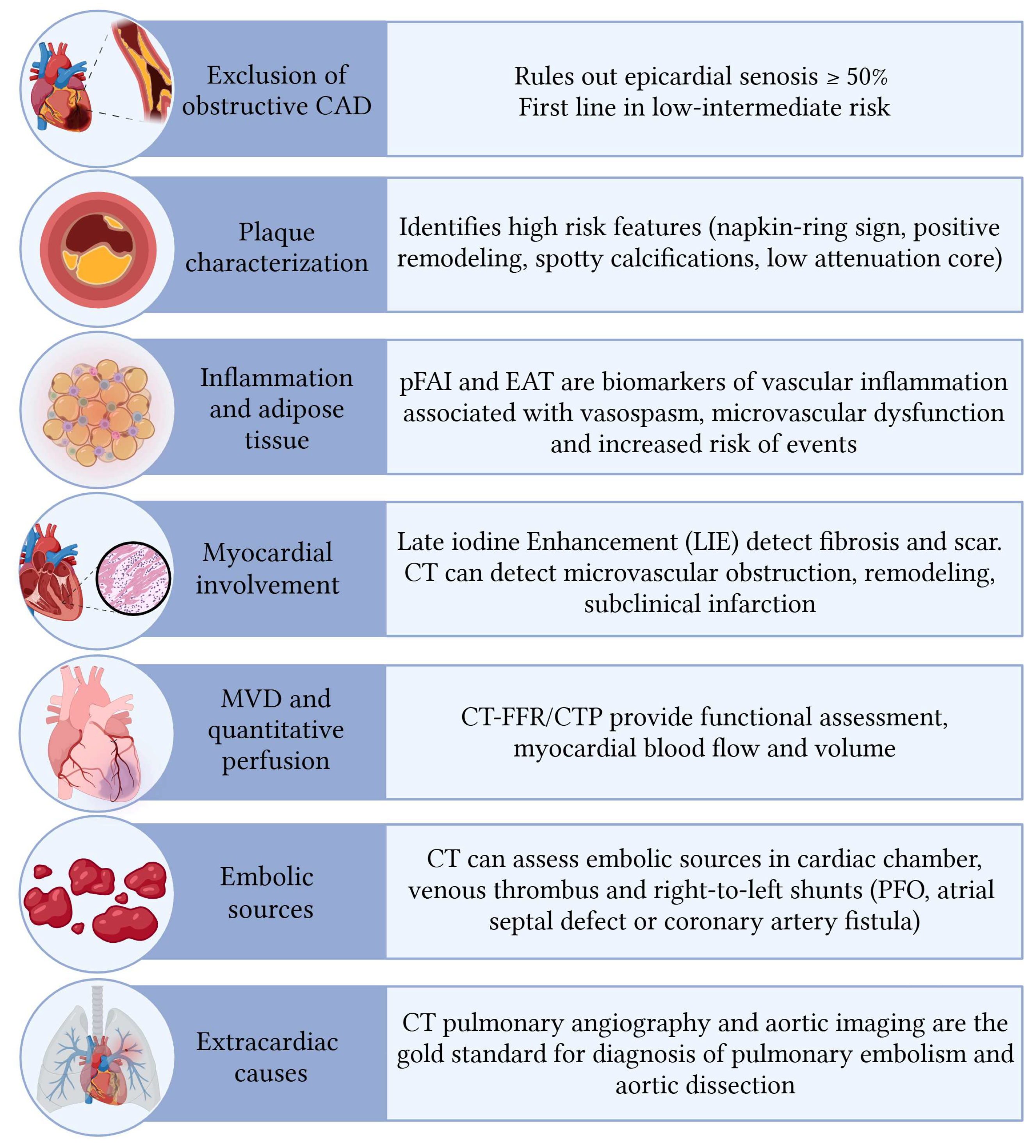

3. Role of CT in NOCAD

3.1. Plaque Characteristics

3.2. Inflammation of Pericoronary and Epicardial Fat

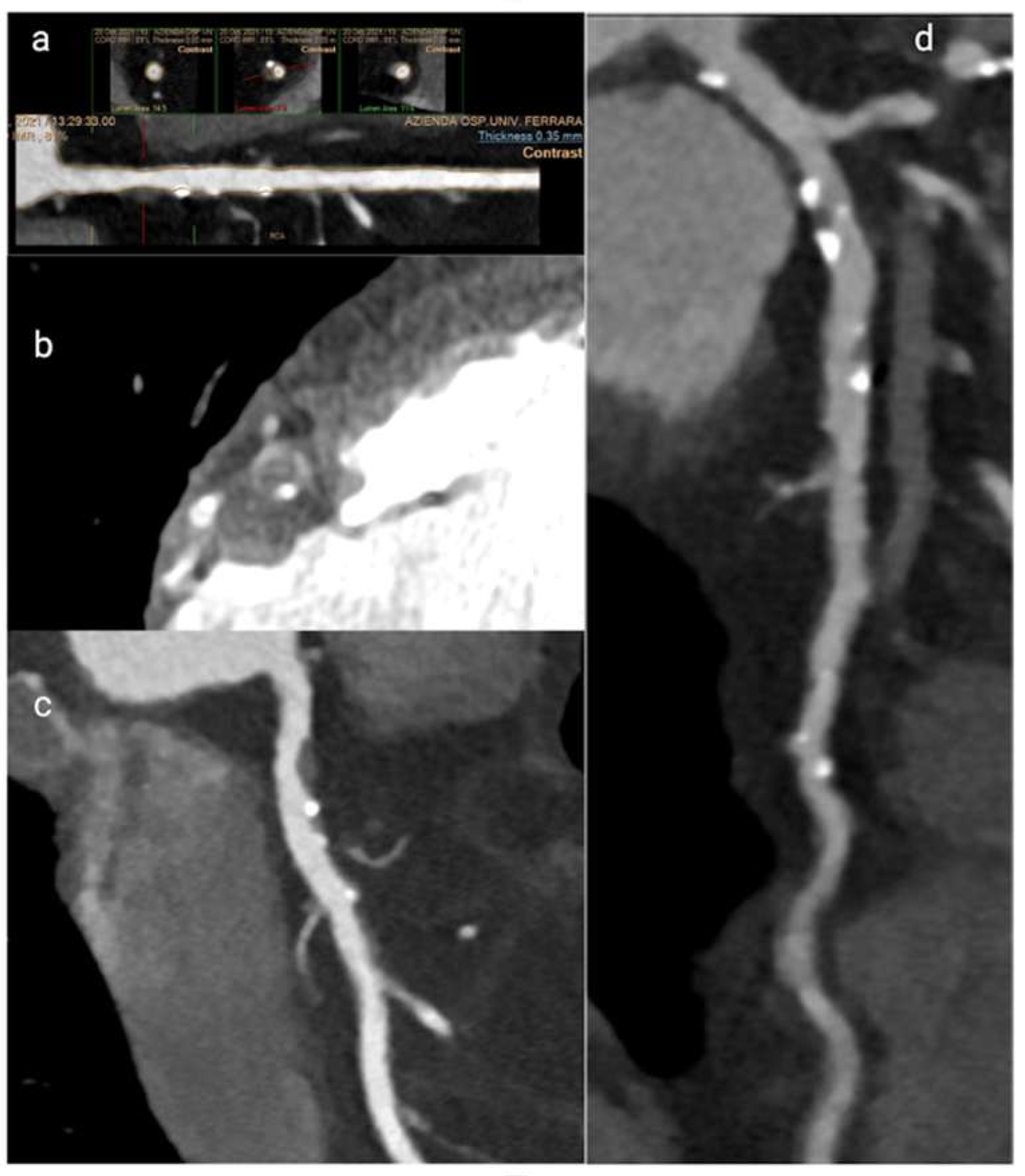

3.3. Vascular Remodelling in Microvascular Dysfunction

3.4. Cardiac CT for Myocardial and Extracardiac Assessment in NOCAD

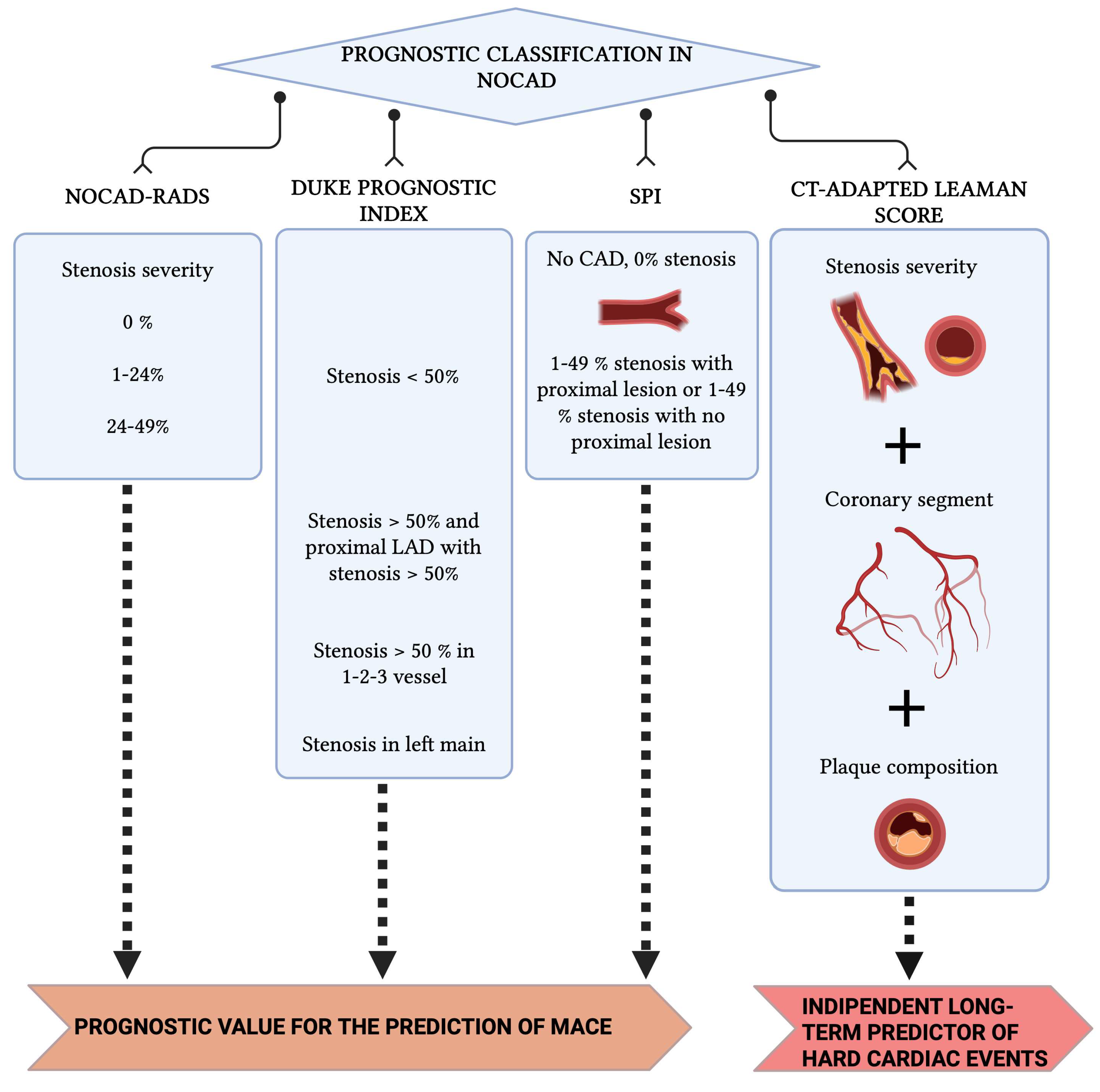

4. Prognostic Classifications Derived from CCT

5. Functional Assessment by Cardiac CT in NOCAD

5.1. The Role of FFR-CT

5.2. The Role of Cardiac CTP

6. Limitations of Cardiac CT in NOCAD

7. Future Perspective

Artificial Intelligence and Radiomics in Plaque Analysis with CT

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAD | Coronary Artery Disease |

| NOCAD | Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease |

| ACS | Acute Coronary Syndrome |

| MI | Myocardial Infarction |

| MINOCA | Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries |

| ANOCA | Angina with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries |

| INOCA | Ischemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries |

| IVUS | Intra Vascular Ultrasounds |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| SCAD | Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection |

| CMD | Coronary Microvascular Disease |

| PE | Pulmonary Embolism |

| PFO | Patent Foramen Ovale |

| MB | Myocardial Bridging |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CCT | Cardiac Computed Tomography |

| FFR-CT | Fractional Flow Reserve Computed Tomography |

| CTP | Computed Tomography Perfusion |

| CMR | Cardiac Magnetic Resonance |

| PCAT | Peri Coronary Adipose Tissue |

| EAT | Epicardial Adipose Tissue |

| pFAI | Peri-coronary Fat Attenuation Index |

| LIE | Late Iodinum Enhancement |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Kunadian, V.; Chieffo, A.; Camici, P.G.; Berry, C.; Escaned, J.; Maas, A.H.E.M.; Prescott, E.; Karam, N.; Appelman, Y.; Fraccaro, C.; et al. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 3504–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, B.A.; Shah, S.M.; Widmer, R.J.; Kobayashi, Y.; Miner, S.E.; Taqueti, V.R.; Jeremias, A.; Albadri, A.; Blair, J.A.; Kearney, K.E.; et al. Comprehensive Management of ANOCA, Part 1—Definition, Patient Population, and Diagnosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 1245–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudurachi, A.; Anghel, L.; Tudurachi, B.S.; Zăvoi, A.; Ceasovschih, A.; Sascău, R.A.; Stătescu, C. Beyond the Obstructive Paradigm: Unveiling the Complex Landscape of Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsen, T.; Asch, F.M.; Davidson, B.; Delgado, V.; DeMaria, A.; Dilsizian, V.; Gaemperli, O.; Garcia, M.J.; Kamp, O.; Lee, D.C.; et al. Non-Invasive Imaging in Coronary Syndromes. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2022, 35, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serruys, P.W.; Kotoku, N.; Nørgaard, B.L.; Garg, S.; Nieman, K.; Dweck, M.R.; Bax, J.J.; Knuuti, J.; Narula, J.; Perera, D.; et al. Computed Tomographic Angiography in Coronary Artery Disease. EuroIntervention 2023, 18, e1307–e1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agewall, S.; Beltrame, J.F.; Reynolds, H.R.; Niessner, A.; Rosano, G.; Caforio, A.L.P.; De Caterina, R.; Zimarino, M.; Roffi, M.; Kjeldsen, K.; et al. ESC working group position paper on myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Jneid, H.; Reynolds, H.R.; Agewall, S.; Brilakis, E.S.; Brown, T.M.; Lerman, A.; Cushman, M.; Kumbhani, D.J.; Arslanian-Engoren, C.; et al. Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of MINOCA. Circulation 2019, 139, e891–e908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.-A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupathy, S.; Air, T.; Dreyer, R.P.; Tavella, R.; Beltrame, J.F. Systematic Review of MINOCA. Circulation 2015, 131, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, H.R.; Smilowitz, N.R. Myocardial Infarction with Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries. Annu. Rev. Med. 2023, 74, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelliccia, F.; Pasceri, V.; Niccoli, G.; Tanzilli, G.; Speciale, G.; Gaudio, C.; Crea, F.; Camici, P.G. Predictors of Mortality in MINOCA. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, 73–83.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, M.; Levy, P.D.; Mukherjee, D.; Amsterdam, E.; Bhatt, D.L.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blankstein, R.; Boyd, J.; Bullock-Palmer, R.P.; Conejo, T.; et al. 2021 AHA/ACC Guideline for Chest Pain. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, e187–e285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virani, S.S.; Newby, L.K.; Arnold, S.V.; Bittner, V.; Brewer, L.C.; Demeter, S.H.; Dixon, D.L.; Fearon, W.F.; Hess, B.; Johnson, H.M.; et al. 2023 AHA/ACC Guideline for Chronic Coronary Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 833–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelliccia, F.; Pepine, C.J.; Berry, C.; Camici, P.G. The role of a comprehensive two-step diagnostic evaluation to unravel the pathophysiology of MINOCA: A review. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 336, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herling De Oliveira, L.L.; Correia, V.M.; Nicz, P.F.G.; Soares, P.R.; Scudeler, T.L. MINOCA: One Size Fits All? J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.N.; Tweet, M.S.; Adlam, D.; Kim, E.S.; Gulati, R.; Price, J.E.; Rose, C.H. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 961–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, T.P.J.; Konst, R.E.; Elias-Smale, S.E.; Oord, S.C.v.D.; Ong, P.; de Vos, A.M.; van de Hoef, T.P.; Paradies, V.; Smits, P.C.; van Royen, N.; et al. Microvascular Dysfunction in ANOCA. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 1471–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancheri, F.; Longo, G.; Vancheri, S.; Henein, M. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaski, J.C.; Crea, F.; Gersh, B.J.; Camici, P.G. Reappraisal of Ischemic Heart Disease. Circulation 2018, 138, 1463–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, K.L.; Johnson, N.P. Coronary Physiology Beyond CFR. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2642–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crea, F.; Montone, R.A.; Rinaldi, R. Pathophysiology of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction. Circ. J. 2022, 86, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, J.D.S.; Corban, M.T.; Prasad, M.; Prasad, A.; Gulati, R.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Myocardial Bridging and Endothelial Dysfunction. EuroIntervention 2020, 15, 1262–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hostiuc, S.; Negoi, I.; Rusu, M.C.; Hostiuc, M. Myocardial Bridging: A Meta-Analysis. J. Forensic Sci. 2018, 63, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leschka, S.; Koepfli, P.; Husmann, L.; Plass, A.; Vachenauer, R.; Gaemperli, O.; Schepis, T.; Genoni, M.; Marincek, B.; Eberli, F.R.; et al. Myocardial Bridging at CT Angiography. Radiology 2008, 246, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Rahman, H.; Rajani, R.; Demir, O.M.; KamWa, M.L.; Morgan, H.; Ezad, S.M.; Ellis, H.; Hogan, D.; Gulati, A.; et al. Mechanisms of Ischemia in Myocardial Bridges. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17, e013657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toya, T.; Naganuma, T.; Suyama, Y.; Hayashi, K.; Adachi, T. Myocardial Bridging and Exercise-Induced Ischemia. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2025, 41, 1973–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montone, R.A.; Gurgoglione, F.L.; Del Buono, M.G.; Rinaldi, R.; Meucci, M.C.; Iannaccone, G.; La Vecchia, G.; Camilli, M.; D’amario, D.; Leone, A.M.; et al. Myocardial Bridging and Coronary Spasm. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e020535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scala, A.; Marchini, F.; Meossi, S.; Zanarelli, L.; Sanguettoli, F.; Frascaro, F.; Bianchi, N.; Cocco, M.; Erriquez, A.; Tonet, E.; et al. Hemodynamic Assessment for CAD Management. Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2024, 72, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuijf, J.D.; Matheson, M.B.; Ostovaneh, M.R.; Arbab-Zadeh, A.; Kofoed, K.F.; Scholte, A.J.H.A.; Dewey, M.; Steveson, C.; Rochitte, C.E.; Yoshioka, K.; et al. INOCA in CORE320 Study. Radiology 2020, 294, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brolin, E.B.; Brismar, T.B.; Collste, O.; Y-Hassan, S.; Henareh, L.; Tornvall, P.; Cederlund, K. Myocardial Bridging in MINOCA. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015, 116, 1833–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampidis, G.P.; Kampaktsis, P.N.; Kouskouras, K.; Samaras, A.; Benetos, G.; Giannopoulos, A.A.; Karamitsos, T.; Kallifatidis, A.; Samaras, A.; Vogiatzis, I.; et al. MINOCA-GR Study Design. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e054698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, R.; Alani, A.; Matsumoto, S.; Li, D.; Fahmy, M.; Abraham, J.; Dailing, C.; Broersen, A.; Kitslaar, P.H.; Nasir, K.; et al. Serial Plaque Volume Assessment. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2018, 45, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villines, T.C.; Rodriguez-Lozano, P. From Stenosis to Plaque Burden. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2814–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.; Gaur, S.; Ovrehus, K.A.; Slomka, P.J.; Betancur, J.; Goeller, M.; Hell, M.M.; Gransar, H.; Berman, D.S.; Achenbach, S.; et al. ML-Based Prediction of Ischemia from CCTA. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 2655–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Knebel Doeberitz, P.L.; De Cecco, C.N.; Schoepf, U.J.; Duguay, T.M.; Albrecht, M.H.; Van Assen, M.; Bauer, M.J.; Savage, R.H.; Pannell, J.T.; De Santis, D.; et al. AI CT-FFR and Plaque Quantification. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 29, 2378–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Kihara, Y.; Kitagawa, T.; Ohashi, N.; Kunita, E.; Iwanaga, Y.; Kobuke, K.; Miyazaki, S.; Kawasaki, T.; Fujimoto, S.; et al. PREDICT Study. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2018, 12, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolossváry, M.; Szilveszter, B.; Merkely, B.; Maurovich-Horvat, P. Plaque imaging with CT—a comprehensive review on coronary CT angiography based risk assessment. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2017, 7, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cury, R.C.; Leipsic, J.; Abbara, S.; Achenbach, S.; Berman, D.; Bittencourt, M.; Budoff, M.; Chinnaiyan, K.; Choi, A.D.; Ghoshhajra, B.; et al. CAD-RADS™ 2.0. Radiol. Cardiothorac. Imaging 2022, 4, e220183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchner, S.B.; Liu, T.; Mayrhofer, T.; Truong, Q.A.; Lee, H.; Fleg, J.L.; Nagurney, J.T.; Udelson, J.E.; Hoffmann, U.; Ferencik, M. High-risk plaque detected on coronary CT angiography predicts acute coronary syndromes independent of significant stenosis in acute chest pain: Results from the ROMICAT-II trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manubolu, V.S.; Roy, S.K.; Budoff, M.J. Serial CCTA Prognostic Value. Curr. Cardiovasc. Imaging Rep. 2022, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaibazzi, N.; Martini, C.; Botti, A.; Pinazzi, A.; Bottazzi, B.; Palumbo, A.A. Coronary Inflammation by PCAT. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e013235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, D.; Suzuki, K.; Fujimoto, D.; Niida, T.; Minami, Y.; Dey, D.; Lee, H.; McNulty, I.; Ako, J.; Ferencik, M.; et al. High-Risk Plaque and Perivascular Inflammation. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2025, 19, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohyama, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Takanami, K.; Ota, H.; Nishimiya, K.; Sugisawa, J.; Tsuchiya, S.; Amamizu, H.; Uzuka, H.; Suda, A.; et al. Perivascular Inflammation in Vasospastic Angina. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerculy, R.; Benedek, I.; Kovács, I.; Rat, N.; Halațiu, V.B.; Rodean, I.; Bordi, L.; Blîndu, E.; Roșca, A.; Mátyás, B.-B.; et al. CT-Assessment of Epicardial Fat Identifies Increased Inflammation at the Level of the Left Coronary Circulation in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, E.K.; Marwan, M.; Desai, M.Y.; Mancio, J.; Alashi, A.; Centeno, E.H.; Thomas, S.; Herdman, L.; Kotanidis, C.; Thomas, K.E.; et al. CRISP-CT Study. Lancet 2018, 392, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Port, J.J.; Weber, B.N.; Kadiyala, M. Inflammation and INOCA. JACC Case Rep. 2025, 30, 103215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Gao, B.; Zheng, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, Z.; Tong, G.; et al. EAT Volume and CAD. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1088961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis, G. Epicardial Adipose Tissue in Cardiology. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusnina, W.; Merdler, I.; Cellamare, M.; Chitturi, K.R.; Chaturvedi, A.; Feuerstein, I.M.; Zhang, C.; Ozturk, S.T.; Deksissa, T.; Sawant, V.; et al. Epicardial Fat and CMD. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e038484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Fan, L. Peri-Coronary Inflammation and Vascular Function. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1303529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, D.; Sansonetti, A.; Ciarlantini, M.; Amicone, S.; Asta, C.; Bavuso, L.; Canton, L.; Fedele, D.; Bodega, F.; Di Iuorio, O.; et al. PCAT after Heart Transplantation. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, ehae666.201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.T.; Sheng, X.C.; Feng, Q.; Yin, Y.; Li, Z.; Ding, S.; Pu, J. pFAI and Vulnerable Plaque. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e022879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mátyás, B.B.; Benedek, I.; Raț, N.; Blîndu, E.; Rodean, I.P.; Haja, I.; Păcurar, D.; Mihăilă, T.; Benedek, T. Coronary Calcification and Perivascular Inflammation. Life 2025, 15, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mátyás, B.B.; Benedek, I.; Raț, N.; Blîndu, E.; Parajkó, Z.; Mihăilă, T.; Benedek, T. Statin Therapy and PCAT. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, L.; De Vita, A.; Villano, A.; Tremamunno, S.; Armillotta, M.; Angeli, F.; Belmonte, M.; Paolisso, P.; Foà, A.; Gallinoro, E.; et al. Imaging in ANOCA. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2025, 50, 103021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for CCS. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3415–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, T.H.; Dilsizian, V. CMD: Clinical Considerations. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, P.; Camici, P.G.; Beltrame, J.F.; Crea, F.; Shimokawa, H.; Sechtem, U.; Kaski, J.C.; Merz, C.N.B. Coronary Vasomotion Disorders International Study Group (COVADIS). Diagnostic Criteria for Microvascular Angina. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 250, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, C.; Sakai, K.; Mizukami, T.; Ohashi, H.; Bouisset, F.; Caglioni, S.; van Hoe, L.; Gallinoro, E.; Bertolone, D.T.; Pardaens, S.; et al. Vascular Remodeling in CMD. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 17, 1463–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, F.; Pompei, G.; D’Aniello, E.; Marrone, A.; Caglioni, S.; Biscaglia, S.; Campo, G.; Tebaldi, M. Treatment of Coronary Vasomotor Disorders. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2024, 38, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-M.; Kim, Y.-W.; Han, S.-W.; Shin, J.-B. Two-Phase Contrast MDCT in MI. Korean J. Radiol. 2007, 8, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, M.; De Filippo, O.; Cura-Curà, G.; Dusi, V.; Di Vita, U.; Gallone, G.; Morena, A.; Palmisano, A.; Pasinato, E.; Solano, A.; et al. Late Iodine Enhancement CT. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 3054–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.M.; Jang, S.; Kim, J.A.; Chun, E.J. MINOCA: Role of CT and MR. Korean J. Radiol. 2020, 21, 1305–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roggel, A.; Hendricks, S.; Dykun, I.; Balcer, B.; Al-Rashid, F.; Risse, J.; Kill, C.; Totzeck, M.; Rassaf, T.; A Mahabadi, A. Wall Motion Abnormalities in ACS. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, ehab724.1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggel, A.; Jehn, S.; Dykun, I.; Balcer, B.; Al-Rashid, F.; Totzeck, M.; Risse, J.; Kill, C.; Rassaf, T.; Mahabadi, A. Focused TTE in Acute Chest Pain. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e085677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitun, S.; Clemente, A.; De Lorenzi, C.; Benenati, S.; Chiappino, D.; Mantini, C.; Sakellarios, A.I.; Cademartiri, F.; Bezante, G.P.; Porto, I. CT Perfusion and FFRCT. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2020, 10, 1954–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.J.E.; Wachsmann, J.; Chamarthy, M.R.; Panjikaran, L.; Tanabe, Y.; Rajiah, P. Imaging of Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2018, 8, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushtaq, S.; De Araujo Gonçalves, P.; Garcia-Garcia, H.M.; Pontone, G.; Bartorelli, A.L.; Bertella, E.; Campos, C.M.; Pepi, M.; Serruys, P.W.; Andreini, D. CT-Leaman Score Validation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 8, e002332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Cao, B.; Du, X.; Li, M.; Huang, J.; Li, Z.; Xiao, J.; Wang, X. Prognostic Value of CTA Classifications. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wetzel, L.; Pope, K.; Meek, L.J.; Rosamond, T.; Walker, C.M. FFRCT: Current Status. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2021, 216, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, P.S.; De Bruyne, B.; Pontone, G.; Patel, M.R.; Norgaard, B.L.; Byrne, R.A.; Curzen, N.; Purcell, I.; Gutberlet, M.; Rioufol, G.; et al. 1-Year Outcomes of FFRCT-Guided Care. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Chen, Q.; Luo, X.; Cao, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, B.; Schoepf, U.J.; Gill, C.E.; Guo, L.; Gao, H.; et al. Prognostic Value of FFRCT in NOCAD. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 8, 778010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Xu, T.; Wang, M.; Xu, L.; Zeng, Y. FFRCT and Atherosclerotic Burden. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 8068–8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuchtner, G.M.; Barbieri, F.; Langer, C.; Beyer, C.; Widmann, G.; Friedrich, G.J.; Cartes-Zumelzu, F.; Plank, F. High-Risk Plaque and Ischemia. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2019, 13, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonet, E.; Pompei, G.; Faragasso, E.; Cossu, A.; Pavasini, R.; Passarini, G.; Tebaldi, M.; Campo, G. CMD: PET, CMR and CT. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, R.C.; Bourque, J.M.; Salerno, M.; Kramer, C.M. Imaging Microvascular Dysfunction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdanowicz, A.; Guzinski, M.; Pula, M.; Witkowska, A.; Reczuch, K. Dynamic CT Myocardial Perfusion. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alessio, A.M.; Bindschadler, M.; Busey, J.M.; Shuman, W.P.; Caldwell, J.H.; Branch, K.R. CT vs PET Myocardial Blood Flow. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, e008323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Buono, M.G.; Montone, R.A.; Camilli, M.; Carbone, S.; Narula, J.; Lavie, C.J.; Niccoli, G.; Crea, F. CMD Across Cardiovascular Diseases. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 1352–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taqui, S.; Ferencik, M.; Davidson, B.P.; Belcik, J.T.; Moccetti, F.; Layoun, M.; Raber, J.; Turker, M.; Tavori, H.; Fazio, S.; et al. CMD by Contrast Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2019, 32, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emfietzoglou, M.; Mavrogiannis, M.C.; Samaras, A.; Rampidis, G.P.; Giannakoulas, G.; Kampaktsis, P.N. Cardiac CT and Adverse Events. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 920119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Choo, G.H.; Ng, K.H. Coronary CT Angiography: Challenges. Br. J. Radiol. 2012, 85, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toia, P.; La Grutta, L.; Sollami, G.; Clemente, A.; Gagliardo, C.; Galia, M.; Maffei, E.; Midiri, M.; Cademartiri, F. Technical Development in Cardiac CT. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2020, 10, 2018–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Soest, G.; Regar, E.; Goderie, T.P.M.; Gonzalo, N.; Koljenović, S.; van Leenders, G.J.; Serruys, P.W.; van der Steen, A.F. Pitfalls in OCT Plaque Characterization. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2011, 4, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Choi, B.W.; Choe, K.O.; Choi, D.; Yoo, K.-J.; Kim, M.-I.; Kim, J. Artifacts in MDCT Coronary Angiography. Radiographics 2004, 24, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z. Cardiac CT Imaging in CAD. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2012, 2, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hada, M.; Hoshino, M.; Sugiyama, T.; Kanaji, Y.; Usui, E.; Hanyu, Y.; Nagamine, T.; Nogami, K.; Ueno, H.; Matsuda, K.; et al. CT Myocardial Perfusion and CMD. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2023, 13, 8423–8434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.P.; Temperley, H.C.; O’sullivan, N.J.; Kenny, A.P.; Murphy, R. Coronary CT Angiography Radiomics for Identifying Coronary Artery Plaque Vulnerability: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J.; Chen, Q.; Pan, T.; Wang, Y.N.; Schoepf, U.J.; Bidwell, S.L.; Qiao, H.; Feng, Y.; Xu, C.; Xu, H..; et al. Coronary CTA Radiomics Model for Vulnerable Plaque. Radiology 2023, 289, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huo, H.; Liu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, Z.; Jiang, X.; Jin, S.; Hou, Y.; Yang, Q.; Teng, F.; et al. Radiomic Signature of PCAT and Plaque Progression. Insights Imaging 2024, 15, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MINOCA | ANOCA/INOCA |

|---|---|

| Plaque disruption (rupture ulceration) | Microvascular dysfunction |

| Coronary vasospasm | Microvascular spasm |

| Coronary thrombosis and embolism | Epicardial spasm |

| Spontaneous coronary dissection | Endothelial dysfunction |

| Takotsubo syndrome | Myocardial bridging |

| CT-Derived Biomarker | Clinical Implications in NOCAD |

|---|---|

| Pericoronary adipose tissue (PCAT) attenuation | Reflects local coronary inflammation; associated with plaque vulnerability and adverse cardiovascular outcomes even in the absence of obstructive stenosis; may improve risk stratification in NOCAD patients. |

| Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) volume and density | Marker of cardiometabolic risk and systemic inflammation; increased EAT burden is linked to coronary inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and worse prognosis in NOCAD. |

| High-risk plaque features (e.g., low-attenuation plaque, positive remodeling, napkin-ring sign) | Identify vulnerable plaques that may underlie ischemia or acute coronary syndromes despite limited luminal narrowing; support intensified preventive therapy. |

| Coronary plaque burden and composition | Total plaque volume and non-calcified plaque components provide prognostic information beyond stenosis severity and help identify higher-risk NOCAD phenotypes. |

| Coronary artery calcium (CAC) score | Indicates overall atherosclerotic burden; useful for long-term risk assessment, although limited in capturing active inflammation or plaque vulnerability in NOCAD. |

| CT-derived radiomics features | Capture microstructural plaque and perivascular tissue characteristics not visible on visual assessment; may enhance prediction of plaque progression and adverse outcomes. |

| AI-based automated plaque analysis | Enables standardized, reproducible quantification of plaque and inflammatory biomarkers; facilitates integration of advanced metrics into clinical workflows and longitudinal monitoring. |

| CT-derived functional indices (e.g., CT-FFR) | Help assess the functional relevance of non-obstructive lesions and identify ischemia-related symptoms in NOCAD patients when anatomy alone is insufficient. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Meossi, S.; Izzo, C.; Rotondo, L.; Sciaramenti, G.; Menzato, E.; Dal Passo, B.; Tezze, R.; Frascaro, F.; Tonet, E.; Marchini, F.; et al. Cardiac CT in Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (NOCAD): A Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010032

Meossi S, Izzo C, Rotondo L, Sciaramenti G, Menzato E, Dal Passo B, Tezze R, Frascaro F, Tonet E, Marchini F, et al. Cardiac CT in Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (NOCAD): A Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeossi, Sofia, Carmen Izzo, Laura Rotondo, Giorgio Sciaramenti, Edoardo Menzato, Beatrice Dal Passo, Renè Tezze, Federica Frascaro, Elisabetta Tonet, Federico Marchini, and et al. 2026. "Cardiac CT in Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (NOCAD): A Literature Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010032

APA StyleMeossi, S., Izzo, C., Rotondo, L., Sciaramenti, G., Menzato, E., Dal Passo, B., Tezze, R., Frascaro, F., Tonet, E., Marchini, F., Campo, G., & Pavasini, R. (2026). Cardiac CT in Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (NOCAD): A Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010032