Characteristics and Risk Factors of Intraoperative Hypothermia in Adults: A Multicenter Prospective Observational Clinical Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design Period and Regions

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Definition of Intraoperative Hypothermia

2.5. Sample Size Calculation and Sampling Method

2.6. Data Collection

2.6.1. Survey Instruments

2.6.2. Survey Method

2.7. Data Quality Control

2.8. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Screening

3.2. Characteristics of Intraoperative Hypothermia

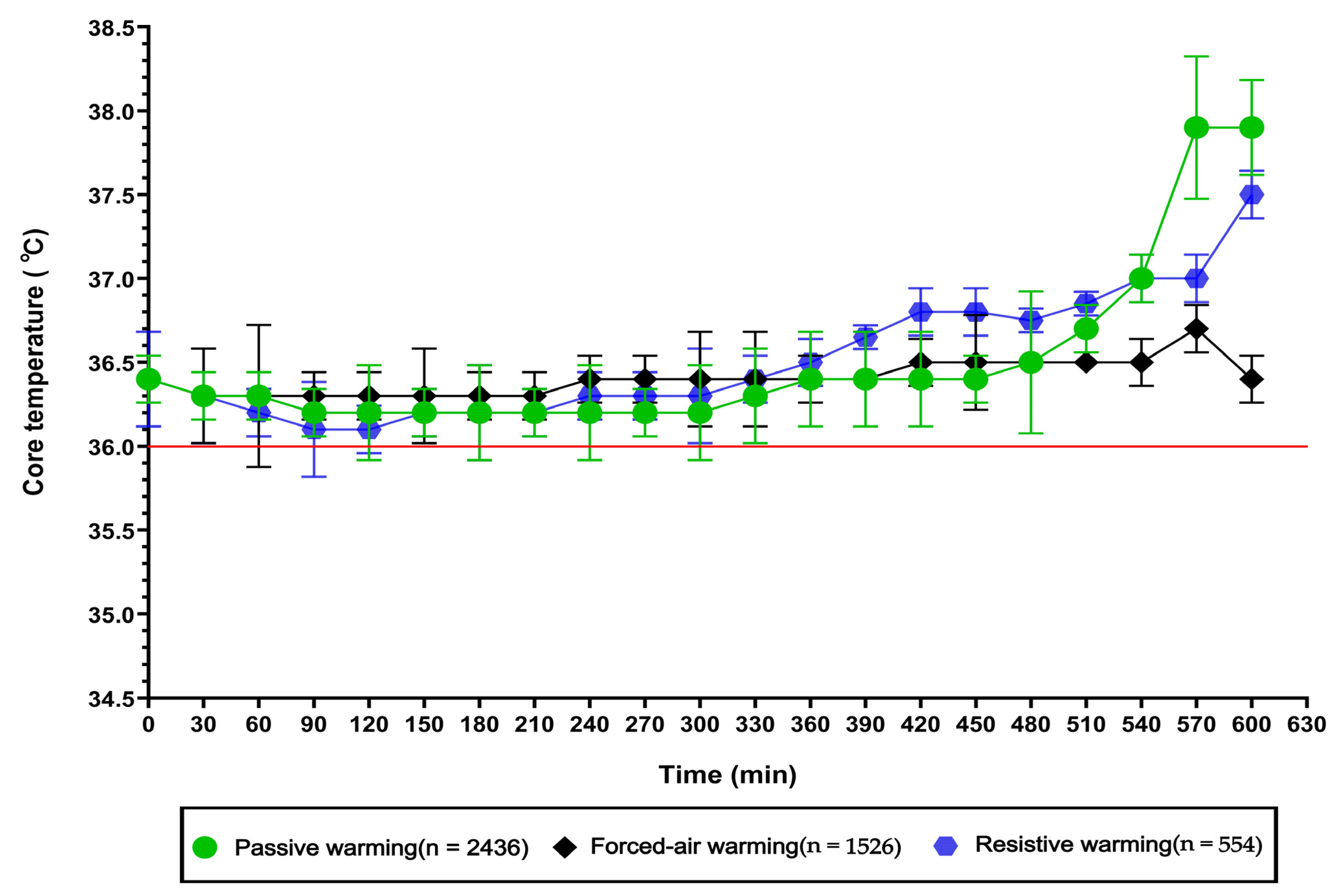

3.3. Intraoperative Core Temperature Changes Under Different Warming Interventions

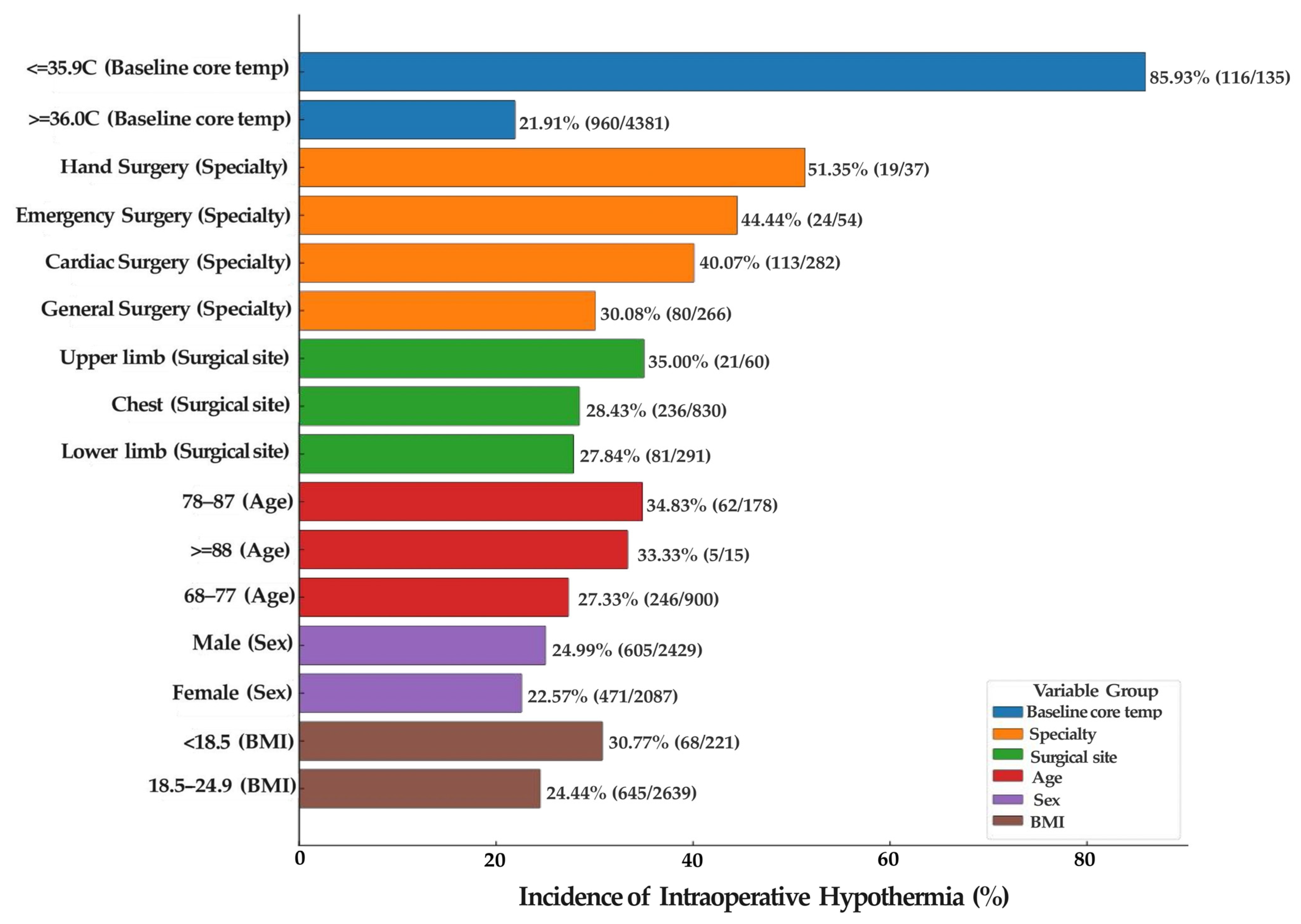

3.4. Univariate Analysis of Risk Factors for Intraoperative Hypothermia

3.5. Multivariable Analysis of Risk Factors for Intraoperative Hypothermia

4. Discussion

4.1. Significance of the Multicenter Clinical Investigation on Intraoperative Hypothermia in Adult Patients

4.2. Analysis of the Characteristics of Intraoperative Hypothermia in Surgical Patients

4.2.1. Analysis of Preoperative Baseline Core Temperature Characteristics

4.2.2. Departmental Analysis of Intraoperative Hypothermia Incidence

4.2.3. Analysis of Surgical Site

4.2.4. Analysis of Age Distribution Characteristics

4.2.5. Analysis of Sex-Related Characteristics

4.2.6. Analysis of BMI Distribution Characteristics

4.3. Analysis of Intraoperative Core Temperature Changes Under Different Warming Interventions

4.4. Analysis of Factors Associated with Intraoperative Hypothermia in Surgical Patients

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Wang, J.-F.; Deng, X.-M. Inadvertent hypothermia: A prevalent perioperative issue that remains to be improved. Anesthesiol. Perioper. Sci. 2023, 1, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L.; Beckmann, J.; Kurz, A. Perioperative complications of hypothermia. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2008, 22, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shou, B.L.; Zhou, A.L.; Ong, C.S.; Alejo, D.E.; DiNatale, J.M.; Larson, E.L.; Lawton, J.S.; Schena, S. Impact of intraoperative blood products, fluid administration, and persistent hypothermia on bleeding leading to reexploration after cardiac surgery. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2024, 168, 873–884.e874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, C.; Andrzejowski, J. Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. BJA Educ. 2018, 18, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oden, T.N.; Doruker, N.C.; Korkmaz, F.D. Compliance of Health Professionals for Prevention of Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia in Adult Patients: A Review. Aana J. 2022, 90, 281–287. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, K.; Xinglian, G.; Wenjing, Y.; Zengyan, W.; Juanjuan, H.; Ying, Y.; Dongping, R. Development and validation of an adult intraoperative hypothermia risk assessment scale. J. Nurs. Sci. 2022, 37, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, S.; Miller, C.; Bräuer, A.; Wallner, B.; Bock, M.; Paal, P. Perioperative Hypothermia-A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, E.; Urrútia, G.; Roqué i Figuls, M.; Pardo-Hernandez, H.; Campos, J.M.; Paniagua, P.; Maestre, L.; Alonso-Coello, P. Active body surface warming systems for preventing complications caused by inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 4, Cd009016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Kim, K.; Oh, E.-a.; Moon, Y.-j.; Kim, Y.-K.; Hwang, J.-H. Effect of electrically heated humidifier on intraoperative core body temperature decrease in elderly patients: A prospective observational study. Anesth. Pain Med. 2016, 11, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.A.; Chang, M.; Lee, S.J.; Sung, T.Y.; Cho, C.K. Prewarming for Prevention of Hypothermia in Older Patients Undergoing Hand Surgery Under Brachial Plexus Block. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2022, 26, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fang, P.; Sun, G.; Li, M. Effect of active forced air warming during the first hour after anesthesia induction and intraoperation avoids hypothermia in elderly patients. BMC Anesth. 2022, 22, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Railton, C.; Tawfic, Q. Tourniquet application during anesthesia: “What we need to know?”. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 32, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Veelen, M.J.; Brodmann Maeder, M. Hypothermia in Trauma. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duryea, E.L.; Nelson, D.B.; Wyckoff, M.H.; Grant, E.N.; Tao, W.; Sadana, N.; Chalak, L.F.; McIntire, D.D.; Leveno, K.J. The impact of ambient operating room temperature on neonatal and maternal hypothermia and associated morbidities: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 505.e501–505.e507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, H.; Khorshid, L. The Effects of Active Warming on Core Body Temperature and Thermal Comfort in Patients After Transurethral Resection of the Prostate: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2023, 32, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oragui, E.; Parsons, A.; White, T.; Longo, U.G.; Khan, W.S. Tourniquet use in upper limb surgery. Hand 2011, 6, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Cen, G.; Sun, J.; Gong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, Z.; Fang, F. Warming with an underbody warming system reduces intraoperative hypothermia in patients undergoing laparoscopic gastrointestinal surgery: A randomized controlled study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikka, R.S.; Prielipp, R.C. Forced air warming devices in orthopaedics: A focused review of the literature. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2014, 96, e200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, A. Thermal care in the perioperative period. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2008, 22, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaney, J.L.; Alexander, L.M.; Kenney, W.L. Sympathetic control of reflex cutaneous vasoconstriction in human aging. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 119, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibasaki, M.; Okazaki, K.; Inoue, Y. Aging and thermoregulation. J. Phys. Fit. Sports Med. 2013, 2, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, E.; Schipa, C.; Cambise, C.; Sollazzi, L.; Aceto, P. Implication of age-related changes on anesthesia management. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2023, 17, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessler, D.I. Temperature monitoring and perioperative thermoregulation. Anesthesiology 2008, 109, 318–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, U.; Ullah, H.; Samad, K. Mean Temperature Loss During General Anesthesia for Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Comparison of Males and Females. Cureus 2021, 13, e17128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, Y.; Kano, M.; Yasuhara, S.; Kobayashi, A.; Tokizawa, K.; Nagashima, K. Estrogen modulates central and peripheral responses to cold in female rats. J. Physiol. Sci. 2010, 60, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Su, L.J.; Wu, H.Z.; Zou, H.; Yang, R.; Zhu, Y.X. Risk factors for inadvertent intraoperative hypothermia in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speakman, J.R. Obesity and thermoregulation. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 156, 431–443. [Google Scholar]

- Özer, A.B.; Yildiz Altun, A.; Erhan, Ö.L.; Çatak, T.; Karatepe, Ü.; Demirel, İ.; Çağlar Toprak, G. The effect of body mass index on perioperative thermoregulation. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2016, 12, 1717–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torossian, A.; Van Gerven, E.; Geertsen, K.; Horn, B.; Van de Velde, M.; Raeder, J. Active perioperative patient warming using a self-warming blanket (BARRIER EasyWarm) is superior to passive thermal insulation: A multinational, multicenter, randomized trial. J. Clin. Anesth. 2016, 34, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, M.; Self, B.; Schroeder, E.; Giap, B. Comparing new-technology passive warming versus traditional passive warming methods for optimizing perioperative body core temperature. Aorn J. 2015, 102, 183.e1–183.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.; Crook, D.; Dasari, K.; Eljelani, F.; El-Haboby, A.; Harper, C.M. Comparison of resistive heating and forced-air warming to prevent inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Br. J. Anaesth. 2016, 116, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Huang, B.; Bao, L.; Wang, J.; Jin, J. Comparing warming strategies to reduce hypothermia and shivering in elderly abdominal or pelvic surgery patients: A network meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-López, P.D.; Montalvo-Afonso, A.; García-Leal, R.; Martín-García, S.; Lagares, A.; Castaño León, A.M.; Gelabert-González, M.; Arán-Echabe, E.; Rodríguez-Arias, C.A.; Khayat, S.; et al. Surgical outcomes in octogenarian meningioma patients: A multicenter retrospective analysis of frailty and radiological predictors: Frailty in octogenarians undergoing meningioma resection. J. Neurooncol. 2025, 175, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torossian, A.; Bräuer, A.; Höcker, J.; Bein, B.; Wulf, H.; Horn, E.P. Preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2015, 112, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, S.; Aksoy, S.M.; But, A. The incidence of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in patients undergoing general anesthesia and an examination of risk factors. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wistrand, C.; Söderquist, B.; Magnusson, A.; Nilsson, U. The effect of preheated versus room-temperature skin disinfection on bacterial colonization during pacemaker device implantation: A randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2015, 4, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, G.; Alderson, P.; Smith, A.F.; Warttig, S. Warming of intravenous and irrigation fluids for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, Cd009891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, F.; Xu, W.; Du, L.; Li, Y.; Liang, A.; Li, B.; Zhang, M. Risk Prediction Models for Perioperative Hypothermia: A Systematic Review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2025, 18, 4443–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Wu, H.; Huang, L.; Liu, S. The prevalence and risk factors of intraoperative hypothermia in patients with hip/knee arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2025, 26, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.H.; Sung, T.Y.; Oh, C.S. Cold temperatures, hot risks: Perioperative hypothermia in geriatric patients—A narrative review. Anesth. Pain Med. 2025, 20, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessler, D.I. Perioperative thermoregulation and heat balance. Lancet 2016, 387, 2655–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagiroglu, G.; Ozturk, G.A.; Baysal, A.; Turan, F.N. Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia and Important Risk Factors during Major Abdominal Surgeries. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2020, 30, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldemir, K.; Gurkan, A.; Yilmaz, F.T. Incidence of Postoperative Hypothermia and Factors Effecting the Development of Hypothermia in Patients Undergoing Abdominal Surgery. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 14, 983. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, B.R.; Forsythe, R.M.; Harbrecht, B.G.; Cuschieri, J.; Minei, J.P.; Maier, R.V.; Moore, E.E.; Billiar, E.E.; Peitzman, A.B.; Sperry, J.L. Hypothermia in massive transfusion: Have we been paying enough attention to it? J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012, 73, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.B.; Phillips-Bute, B.; Bhattacharya, S.D.; Shah, A.A.; Andersen, N.D.; Altintas, B.; Lima, B.; Smith, P.K.; Hughes, G.C.; Welsby, I.J. Predictors of massive transfusion with thoracic aortic procedures involving deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. J. Thorac Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 141, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Hong, X.; Jiang, C.; Chen, Y. Effects of warming needle moxibustion on postoperative rehabilitation, pain degree, immune function, and upper limb lymphedema in patients with breast cancer undergoing radical mastectomy. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2025, 15, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Category | Total Surgeries (n) | Hypothermia Cases (n) | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Core Temperature (°C) | ≤35.9 | 135 | 116 | 85.93 |

| ≥36.0 | 4381 | 960 | 21.91 | |

| Surgical Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology | 194 | 27 | 13.92 |

| Orthopedics | 699 | 150 | 21.46 | |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 271 | 44 | 16.24 | |

| Hepatobiliary Surgery | 622 | 144 | 23.15 | |

| Thyroid/Breast Surgery | 239 | 54 | 22.59 | |

| Urology | 488 | 110 | 22.54 | |

| Thoracic Surgery | 424 | 102 | 24.06 | |

| Gastrointestinal Surgery | 529 | 116 | 21.93 | |

| Hand Surgery | 37 | 19 | 51.35 | |

| Stomatology | 33 | 7 | 21.21 | |

| General Surgery | 266 | 80 | 30.08 | |

| Neurosurgery | 320 | 80 | 25.00 | |

| Vascular Surgery | 39 | 6 | 15.38 | |

| Emergency Surgery | 54 | 24 | 44.44 | |

| Cardiovascular Surgery | 282 | 113 | 40.07 | |

| Surgical Site | Head and Neck | 751 | 165 | 21.97 |

| Thoracic | 830 | 236 | 28.43 | |

| Abdominal | 2124 | 501 | 23.59 | |

| Back | 322 | 42 | 13.04 | |

| Upper Extremity | 60 | 21 | 35.00 | |

| Lower Extremity | 291 | 81 | 27.84 | |

| Pelvis and Perineum | 134 | 27 | 20.15 | |

| Age (years) | 18–27 | 233 | 39 | 16.74 |

| 28–37 | 412 | 68 | 16.50 | |

| 38–47 | 539 | 107 | 19.85 | |

| 48–57 | 1014 | 245 | 24.16 | |

| 58–67 | 1225 | 301 | 24.57 | |

| 68–77 | 900 | 246 | 27.33 | |

| 78–87 | 178 | 62 | 34.83 | |

| ≥88 | 15 | 5 | 33.33 | |

| Sex | Male | 2429 | 605 | 24.99 |

| Female | 2087 | 471 | 22.57 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 221 | 68 | 30.77 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 2639 | 645 | 24.44 | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 1390 | 293 | 21.08 | |

| ≥30.0 | 266 | 43 | 16.17 |

| Variable | Category | Total Surgeries (n) | Hypothermia Cases (n) | χ2 | p |

| Preoperative Bowel Preparation | None | 3344 | 787 | 0.609 | 0.737 |

| Oral laxatives | 898 | 221 | |||

| Cleansing enema | 274 | 68 | |||

| Anesthesia Type | Regional anesthesia | 58 | 11 | 6.584 | 0.037 |

| General anesthesia | 4165 | 978 | |||

| Combined anesthesia (general + regional) | 293 | 87 | |||

| ASA Classification | I–II | 3238 | 678 | 55.850 | <0.001 |

| III | 1194 | 365 | |||

| ≥IV | 84 | 33 | |||

| Surgical Approach | Superficial or soft tissue | 1274 | 289 | 11.143 | 0.004 |

| Minimally invasive (laparoscopic, endoscopic, microscopic) | 2485 | 571 | |||

| Open surgery (thoracic, abdominal, pelvic) | 757 | 216 | |||

| Operating Room Cleanliness | Ten-thousand class | 2331 | 550 | 0.648 | 0.723 |

| Thousand class | 918 | 214 | |||

| Hundred class | 1267 | 312 | |||

| Skin Disinfection Site | Head and neck | 749 | 140 | 27.297 | <0.001 |

| Extremities | 530 | 166 | |||

| Thorax/Abdomen/Back | 3235 | 769 | |||

| Volume of Intravenous Cold Fluid (mL) | <1000 | 1425 | 231 | 77.862 | <0.001 |

| 1000~2000 | 2359 | 611 | |||

| >2000 | 732 | 234 | |||

| Volume of Cold Irrigation Fluid (mL) | <1000 | 2844 | 670 | 0.430 | 0.806 |

| 1000~2000 | 1173 | 282 | |||

| >2000 | 499 | 124 | |||

| Intraoperative Allogeneic Blood Transfusion (U) | <2 | 4279 | 987 | 26.137 | <0.001 |

| 2~4 | 210 | 78 | |||

| >4 | 27 | 11 | |||

| Intraoperative Blood Loss (mL) | <400 | 4280 | 987 | 26.500 | <0.001 |

| 400~800 | 195 | 73 | |||

| >800 | 41 | 16 | |||

| Surgical Duration (h) | <2 | 1712 | 241 | 177.803 | <0.001 |

| 2~4 | 1951 | 521 | |||

| >4 | 853 | 314 |

| Variable | β | SE | Waldχ2 | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of anesthesia (1 = Regional; 2 = General; 3 = Combined) | 0.556 | 0.376 | 2.184 | 0.140 | 1.743 | 0.834–3.644 |

| ASA classification (1 = I–II, 2 = III, 3 = IV) | 0.342 | 0.083 | 17.063 | <0.001 | 1.408 | 1.197–1.657 |

| Surgical approach (1 = Superficial/Soft Tissue Surgery; 2 = Minimally Invasive Surgery; 3 = Open Surgery) | −0.308 | 0.124 | 6.212 | 0.013 | 0.735 | 0.577–0.936 |

| Skin disinfection site (1 = Head/Neck, 2 = Extremities, 3 = Thorax/Abdomen/Back) | 0.705 | 0.141 | 24.870 | <0.001 | 2.024 | 1.534–2.670 |

| Volume of cold intravenous fluids infused (mL) (1 ≤ 1000, 2 = 1000–2000, 3 ≥ 2000) | 0.311 | 0.092 | 11.509 | 0.001 | 1.365 | 1.140–1.633 |

| Volume of transfused blood (U) (1 ≤ 2 2 = 2–4 3 ≥ 4) | 0.110 | 0.165 | 0.441 | 0.507 | 1.116 | 0.807–1.542 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) (1 ≤ 400, 2 = 400–800, 3 ≥ 800) | 0.225 | 0.173 | 1.689 | 0.194 | 1.252 | 0.892–1.756 |

| Duration of surgery (h) (1 ≤ 2, 2 = 2–4, 3 ≥ 4) | 0.700 | 0.092 | 58.262 | <0.001 | 2.014 | 1.683–2.411 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Gao, X.; Ke, W.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Q.; Yu, W.; Hu, J.; on behalf of the Intraoperative Hypothermia Investigators (12-Center Consortium). Characteristics and Risk Factors of Intraoperative Hypothermia in Adults: A Multicenter Prospective Observational Clinical Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010031

Zhang H, Gao X, Ke W, Wang Z, Ma Q, Yu W, Hu J, on behalf of the Intraoperative Hypothermia Investigators (12-Center Consortium). Characteristics and Risk Factors of Intraoperative Hypothermia in Adults: A Multicenter Prospective Observational Clinical Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hanqing, Xinglian Gao, Wen Ke, Zengyan Wang, Qiong Ma, Wenjing Yu, Juanjuan Hu, and on behalf of the Intraoperative Hypothermia Investigators (12-Center Consortium). 2026. "Characteristics and Risk Factors of Intraoperative Hypothermia in Adults: A Multicenter Prospective Observational Clinical Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010031

APA StyleZhang, H., Gao, X., Ke, W., Wang, Z., Ma, Q., Yu, W., Hu, J., & on behalf of the Intraoperative Hypothermia Investigators (12-Center Consortium). (2026). Characteristics and Risk Factors of Intraoperative Hypothermia in Adults: A Multicenter Prospective Observational Clinical Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010031