Ectopic Pregnancy with a Normally Located Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System in a Woman with Adenomyosis: Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

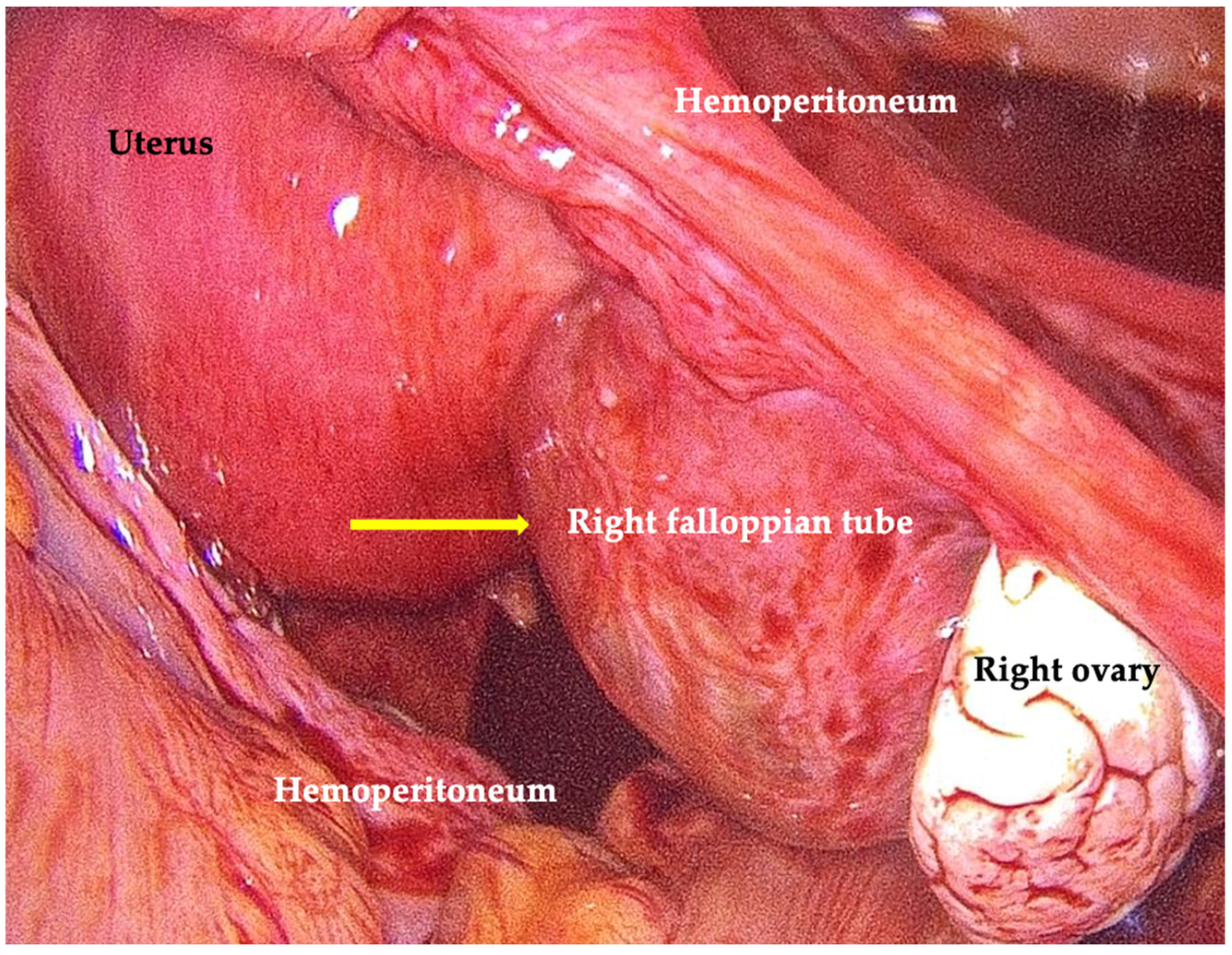

2. Case Presentation

3. Literature Review

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nocita, E.; Martire, F.G.; Paladino, C.; Monaco, G.; Iacobini, F.; Valeriani, S.; Soreca, G.; Russo, C.; Exacoustos, C. Ultrasound Follow-Up in young women with severe dysmenorrhea predicts early onset of endometriosis. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2025, 54, 103003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martire, F.G.; Costantini, E.; D’abate, C.; Schettini, G.; Sorrenti, G.; Centini, G.; Zupi, E.; Lazzeri, L. Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: From Pathogenesis to Follow-Up. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzeri, L.; Andersson, K.L.; Angioni, S.; Arena, A.; Arena, S.; Bartiromo, L.; Berlanda, N.; Bonin, C.; Candiani, M.; Centini, G.; et al. How to Manage Endometriosis in Adolescence: The Endometriosis Treatment Italian Club Approach. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selntigia, A.; Exacoustos, C.; Ortoleva, C.; Russo, C.; Monaco, G.; Martire, F.G.; Rizzo, G.; Della-Morte, D.; Mercuri, N.B.; Albanese, M. Correlation between endometriosis and migraine features: Results from a prospective case-control study. Cephalalgia 2024, 44, 3331024241235210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Istat. Births and Fertility of the Resident Population—Year 2024; ISTAT: Rome, Italy, 2024. Available online: https://www.istat.it/en/press-release/births-and-fertility-of-the-resident-population-year-2024/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Bandini, V.; Buggio, L.; Berlanda, N.; Somigliana, E. Association of endometriosis and adenomyosis with pregnancy and infertility. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 119, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.M.; Samy, A.; Atwa, K.; Ghoneim, H.M.; Lotfy, M.; Mohammed, H.S.; Abdellah, A.M.; El Bahie, A.M.; Aboelroose, A.A.; El Gedawy, A.M.; et al. The role of levonorgestrel intra-uterine system in the management of adenomyosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020, 99, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Shi, J.; Gu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Yan, H.; Li, Q.; Lyu, S.; Dai, Y.; et al. The role of different LNG-IUS therapies in the management of adenomyosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2025, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millischer, A.-E.; Santulli, P.; Da Costa, S.; Bordonne, C.; Cazaubon, E.; Marcellin, L.; Chapron, C. Adolescent endometriosis: Prevalence increases with age on magnetic resonance imaging scan. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 119, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upson, K.; Missmer, S.A. Epidemiology of Adenomyosis. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2020, 38, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martire, F.G.; D’abate, C.; Costantini, E.; De Bonis, M.; Sorrenti, G.; Centini, G.; Zupi, E.; Lazzeri, L. Sonographic and Clinical Progression of Adenomyosis and Coexisting Endometriosis: Long-Term Insights and Management Perspectives. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, J.; Sterrenburg, M.; Lane, S.; Maheshwari, A.; Li, T.C.; Cheong, Y. Reproductive, obstetric, and perinatal outcomes of women with adenomyosis and endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2019, 25, 592–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, K.Y.; de Waard, L.; Oza, M.; van Wely, M.; Jurkovic, D.; Memtsa, M.; Woolner, A.; Mol, B.W. Ectopic pregnancy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadakekut, E.S.; Gnugnoli, D.M. Ectopic Pregnancy. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539860/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Papageorgiou, D.; Sapantzoglou, I.; Prokopakis, I.; Zachariou, E. Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy: From Diagnosis to Treatment. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitzerd, E.; Bogers, H.; Kianmanesh Rad, N.A.; Duvekot, J.J. A viable caesarean scar pregnancy in a woman using a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device: A case report. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2018, 23, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.L.; Beasley, L.M. Pregnant with a perforated levonorgestrel intrauterine system and visible threads at the cervical os. BMJ Case Rep. 2017, 2017, bcr2017220071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resta, C.; Dooley, W.M.; Malligiannis Ntalianis, K.; Burugapalli, S.; Hussain, M. Ectopic Pregnancy in a Levonogestrel-Releasing Intrauterine Device User: A Case Report. Cureus 2021, 13, e18867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, S.R.; Melchor, J.; Ripps, S.J.; Burgess, J. Ectopic Pregnancy Observed With Kyleena Intrauterine Device Use: A Case Report. Cureus 2023, 15, e35637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makena, D.; Gichere, I.; Warfa, K. Levonorgestrel intrauterine system embedded within tubal ectopic pregnancy: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2021, 15, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetani, S.L.; Garbade, G.J.; Haas, S.I.; Roth, K.R.; Kane, K.E. A ruptured ectopic pregnancy in a patient with an intrauterine device: A case report. Radiol. Case Rep. 2021, 16, 3672–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasowiec, L.; Kufelnicka-Babout, M.; Sieroszewski, P. Right-sided ovarian ectopic pregnancy with Jaydess in situ. Ginekol. Pol. 2020, 91, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antequera, A.; Babar, Z.; Balachandar, C.; Johal, K.; Sapundjieski, M.; Qandil, N. Managing Ruptured Splenic Ectopic Pregnancy Without Splenectomy: Case Report and Literature Review. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 28, 2323–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihangir, U.; Ebru, A.; Murat, E.; Levent, Y. Mechanism of action of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2013, 123, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopp-Kallner, H.; Linder, M.; Cesta, C.E.; Segovia Chacón, S.; Kieler, H.; Graner, S. Method of Hormonal Contraception and Protective Effects Against Ectopic Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 139, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ectopic Pregnancy and Miscarriage: Diagnosis and Initial Management; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2023.

- Li, C.; Zhao, W.-H.; Meng, C.-X.; Ping, H.; Qin, G.-J.; Cao, S.-J.; Xi, X.; Zhu, Q.; Li, X.-C.; Zhang, J. Contraceptive Use and the Risk of Ectopic Pregnancy: A Multi-Center Case-Control Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, J.; Malik, S.; Dua, M. True Mirena failure: Twin pregnancy with Mirena in situ. J. Midlife Health 2013, 4, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.Q.; Tien, C.T.; Ding, D.C. Early intrauterine pregnancy with an intrauterine device in place and terminated with spontaneous abortion: A case report. Medicine 2024, 103, e37843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaidi, A.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Lidegaard, Ø.; Mørch, L.S. Ectopic Pregnancy Risk in Users of Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine Systems With 52, 19.5, and 13.5 mg of Hormone. JAMA 2023, 329, 935–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, K.; Reed, S.; Moehner, S.; Minh, T.D. Comparative contraceptive effectiveness of levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices: The European Active Surveillance Study for Intrauterine Devices. Contraception 2015, 91, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.T.; Lukkari-Lax, E.; Schulze, A.; Wahdan, Y.; Serrani, M.; Kroll, R. Contraceptive efficacy and safety of the 52-mg levonorgestrel intrauterine system for up to 8 years: Findings from the Mirena Extension Trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 227, 873.e1–873.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creinin, M.D.; Schreiber, C.A.; Turok, D.K.; Cwiak, C.; Chen, B.A.; Olariu, A.I. Levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system efficacy and safety through 8 years of use. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 227, 871.e1–871.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creinin, M.D.; Barnhart, K.T.; Gawron, L.M.; Eisenberg, D.; Mabey, R.G., Jr.; Jensen, J.T. Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Treatment With a Levonorgestrel 52-mg Intrauterine Device. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 141, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bofill Rodriguez, M.; Lethaby, A.; Jordan, V. Progestogen-releasing intrauterine systems for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 6, CD002126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, T.; Jiang, R. Efficacy of drugs treatment in patients with endometrial hyperplasia with or without atypia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine 2024, 103, e39619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulino, F.A.; Dilisi, V.; Capriglione, S.; Cannone, F.; Catania, F.; Martire, F.G.; Tuscano, A.; Gulisano, M.; D’uRso, V.; Di Stefano, A.; et al. Anti-Mullerian Hormone (AMH) and adenomyosis: Mini-review of literature of the last 5 years. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1014519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poordast, T.; Naghmehsanj, Z.; Vahdani, R.; Alamdarloo, S.M.; Ashraf, M.A.; Samsami, A.; Najib, F.S. Evaluation of the recurrence and fertility rate following salpingostomy in patients with tubal ectopic pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martire, F.G.; Russo, C.; Selntigia, A.; Siciliano, T.; Lazzeri, L.; Piccione, E.; Zupi, E.; Exacoustos, C. Transvaginal ultrasound evaluation of the pelvis and symptoms after laparoscopic partial cystectomy for bladder endometriosis. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2022, 23, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martire, F.G.; Zupi, E.; Lazzeri, L.; Morosetti, G.; Conway, F.; Centini, G.; Solima, E.; Pietropolli, A.; Piccione, E.; Exacoustos, C. Transvaginal Ultrasound Findings After Laparoscopic Rectosigmoid Segmental Resection for Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis. J. Ultrasound Med. 2021, 40, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, B.; Russo, C.; Mossa, M.; Martire, F.G.; Selntigia, A.; Mancone, R.; Calabrese, E.; Rizzo, G.; Exacoustos, C.; Biancone, L. High Frequency of Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nested Case-Control Study. Dig. Dis. 2023, 41, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhigbe, R.E.; Afolabi, O.A.; Adegbola, C.A.; Akhigbe, T.M.; Oyedokun, P.A.; Afolabi, O.A. Comparison of the effectiveness of levonorgestrel intrauterine system and dienogest in the management of adenomyosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 300, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, S.; Xie, X.; Yi, J.; Liu, X.; Guo, S.W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of reproductive outcomes after high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) treatment of adenomyosis. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 92, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selntigia, A.; Molinaro, P.; Tartaglia, S.; Pellicer, A.; Galliano, D.; Cozzolino, M. Adenomyosis: An Update Concerning Diagnosis, Treatment, and Fertility. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, A.; Fruscalzo, A.; Dedes, I.; Mueller, M.D.; Londero, A.P.; Marti, C.; Guani, B.; Feki, A. Advances in Adenomyosis Treatment: High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound, Percutaneous Microwave Therapy, and Radiofrequency Ablation. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Gynecologic Practice; Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Expert Work Group. Committee Opinion No 672: Clinical Challenges of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Methods. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, e69–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullany, K.; Minneci, M.; Monjazeb, R.; Coiado, O.C. Overview of ectopic pregnancy diagnosis, management, and innovation. Womens Health 2023, 19, 17455057231160349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 191: Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, e65–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fee, N.; Begley, B.; McArdle, A.; Milne, S.; Freyne, A.; Fionnovola, A. National Clinical Practice Guideline: The Diagnosis and Management of Ectopic Pregnancy, National Women and Infants Health Programme; The Institute of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: Dublin 2, Ireland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, S.C.; A Moakes, C.; Doust, A.M.; Mol, B.W.; Duncan, W.C.; Tong, S.; Horne, A.W.; Whitaker, L.H.R. Early (Days 1-4) post-treatment serum hCG level changes predict single-dose methotrexate treatment success in tubal ectopic pregnancy. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 38, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisharah, M.; Alrashidi, H.M.; Almilad, H.I.; Almuharimi, A.A.; Alshehri, W.A.; Aljuhani, R.M.; Almutairi, A.K.; Hazazi, I.S.J.; Adawi, N.M.; Almarashi, S.A.; et al. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy in the surgical management of ectopic pregnancy: Integrative literature review. Saudi Med. Horiz. J. 2022, 3, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenjing, L.; Haibo, L. Therapeutic effect of laparoscopic salpingotomy vs. salpingectomy on patients with ectopic pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 997490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 193: Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, e91–e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESHRE Guideline Group on Ectopic Pregnancy. Management of women with ectopic pregnancy. Hum. Reprod. Open 2023, 2023, hoad017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.D.; Chen, L.; Tymm, C.; Xu, X.; Ferris, J.S.; Hershman, D.L.; Hagemann, A.R.; Skeete, D.; Curran, T.; Westfal, M.; et al. Population-Level Reduction in Ovarian Cancer Through Performance of Opportunistic Salpingectomy at the Time of Cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 2025, 2025, 10-1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.; Carter, J.; Reid, G.; Krishnan, S.; Ludlow, J.; Cooper, M.; Abbott, J. The effect of laparoscopic salpingectomy for ectopic pregnancy on ovarian reserve. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 60, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Kitahara, Y.; Hasegawa, Y.; Tsukui, Y.; Hiraishi, H.; Iwase, A. Effect of salpingectomy on ovarian reserve: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2022, 48, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenbeek, M.P.; van Bommel, M.H.D.; Inthout, J.; Peterson, C.B.; Simons, M.; Roes, K.C.B.; Kets, M.; Norquist, B.M.; Swisher, E.M.; Hermens, R.P.M.G.; et al. TUBectomy with delayed oophorectomy as an alternative to risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in high-risk women to assess the safety of prevention: The TUBA-WISP II study protocol. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundur, M.; Bhati, P.; Girish, B.K.; Vs, S.; Nair, I.R.; Pavithran, K.; Rajanbabu, A. Endometriosis in clear cell and endometrioid carcinoma ovary: Its impact on clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcomes. Ecancermedicalscience 2023, 17, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, M.E.; Farland, L.V.; Yan, B.; Wang, J.; Trabert, B.; Doherty, J.A.; Meeks, H.D.; Madsen, M.; Guinto, E.; Collin, L.J.; et al. Endometriosis typology and ovarian cancer risk. JAMA 2024, 332, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associazione Italiana di Oncologia Medica. Ovarian, Fallopian Tube and Primary Peritoneal Neoplasms: Guidelines, Version 2024; AIOM: Milano, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kindelberger, D.W.; Lee, Y.; Miron, A.; Hirsch, M.S.; Feltmate, C.; Medeiros, F.; Callahan, M.J.; Garner, E.O.; Gordon, R.W.; Birch, C.; et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: Evidence for a causal relationship. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2007, 31, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luvero, D.; Angioli, R.; Notaro, E.; Plotti, F.; Terranova, C.; Angioli, A.M.; Festa, A.; Stermasi, A.; Manco, S.; Diserio, M.; et al. Serous Tubal Intraepithelial Carcinoma (STIC): A Review of the Literature on the Incidence at the Time of Prophylactic Surgery. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbeek, M.P.; Harmsen, M.G.; Hoogerbrugge, N.; de Jong, M.A.; Maas, A.H.E.M.; Prins, J.B.; Bulten, J.; Teerenstra, S.; van Bommel, M.H.D.; van Doorn, H.C.; et al. Association of Salpingectomy With Delayed Oophorectomy Versus Salpingo-oophorectomy With Quality of Life in BRCA1/2 Pathogenic Variant Carriers: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bommel, M.H.D.; Steenbeek, M.P.; Inthout, J.; Van Garderen, T.; Harmsen, M.G.; Jong, M.A.; Maas, A.H.E.M.; Prins, J.B.; Bulten, J.; Van Doorn, H.C.; et al. Salpingectomy With Delayed Oophorectomy Versus Salpingo-Oophorectomy in BRCA1/2 Carriers: Three-Year Outcomes of a Prospective Preference Trial. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2025, 132, 782–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Raz, Y.; Recouvreux, M.S.; Diniz, M.A.; Lester, J.; Karlan, B.Y.; Walts, A.E.; Gertych, A.; Orsulic, S. Focal Serous Tubal Intra-Epithelial Carcinoma Lesions Are Associated With Global Changes in the Fallopian Tube Epithelia and Stroma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 853755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Age (Years) | Parity | Clinical Data | LNG-IUS Dosage | IUS Position | Ectopic Pregnancy Location | Interval from LNG-IUS Insertion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hitzerd, E., et al. (2018). [16] | 36 | Multiparous | Previous cesarean section | 52 mg | In situ | Cesarean scar pregnancy | 60 months |

| Howard, et al. (2017). [17] | 31 | Multiparous | Not specified | 52 mg | Displaced | Left adnexa | 54 months |

| Resta, C., et al. (2021). [18] | 36 | Multiparous | Not specified | 52 mg | In situ | Left tubal | 12 months |

| Singer, S. R., et al. (2023). [19] | 31 | Multiparous | Not specified | 19.5 mg | In situ | Left tubal | 36 months |

| Makena, D., et al. (2021). [20] | 34 | Primiparous | Not specified | 52 mg | Displaced | Left tubal | 24 months |

| Gaetani, S. L., et al. (2021). [21] | 30 | Multiparous | Not specified | Not specified | In situ | Right tubal | 24 months |

| Panasowiec, L., et al. (2020). [22] | 33 | Multiparous | Not specified | 13.5 mg | In situ | Right ovarian | Not specified |

| Antequera, A., et al. (2021). [23] | 36 | Multiparous | Not specified | Not specified | In situ | Spleen | 4 months |

| Present case | 39 | Multiparous | Adenomyosis | 19.5 mg | In situ | Right tubal | 18 months |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Martire, F.G.; Costantini, E.; Zupi, E.; Lazzeri, L. Ectopic Pregnancy with a Normally Located Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System in a Woman with Adenomyosis: Case Report and Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010272

Martire FG, Costantini E, Zupi E, Lazzeri L. Ectopic Pregnancy with a Normally Located Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System in a Woman with Adenomyosis: Case Report and Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):272. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010272

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartire, Francesco Giuseppe, Eugenia Costantini, Errico Zupi, and Lucia Lazzeri. 2026. "Ectopic Pregnancy with a Normally Located Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System in a Woman with Adenomyosis: Case Report and Literature Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010272

APA StyleMartire, F. G., Costantini, E., Zupi, E., & Lazzeri, L. (2026). Ectopic Pregnancy with a Normally Located Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System in a Woman with Adenomyosis: Case Report and Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010272