Comparative Efficacy of Autologous Hematopoietic and Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

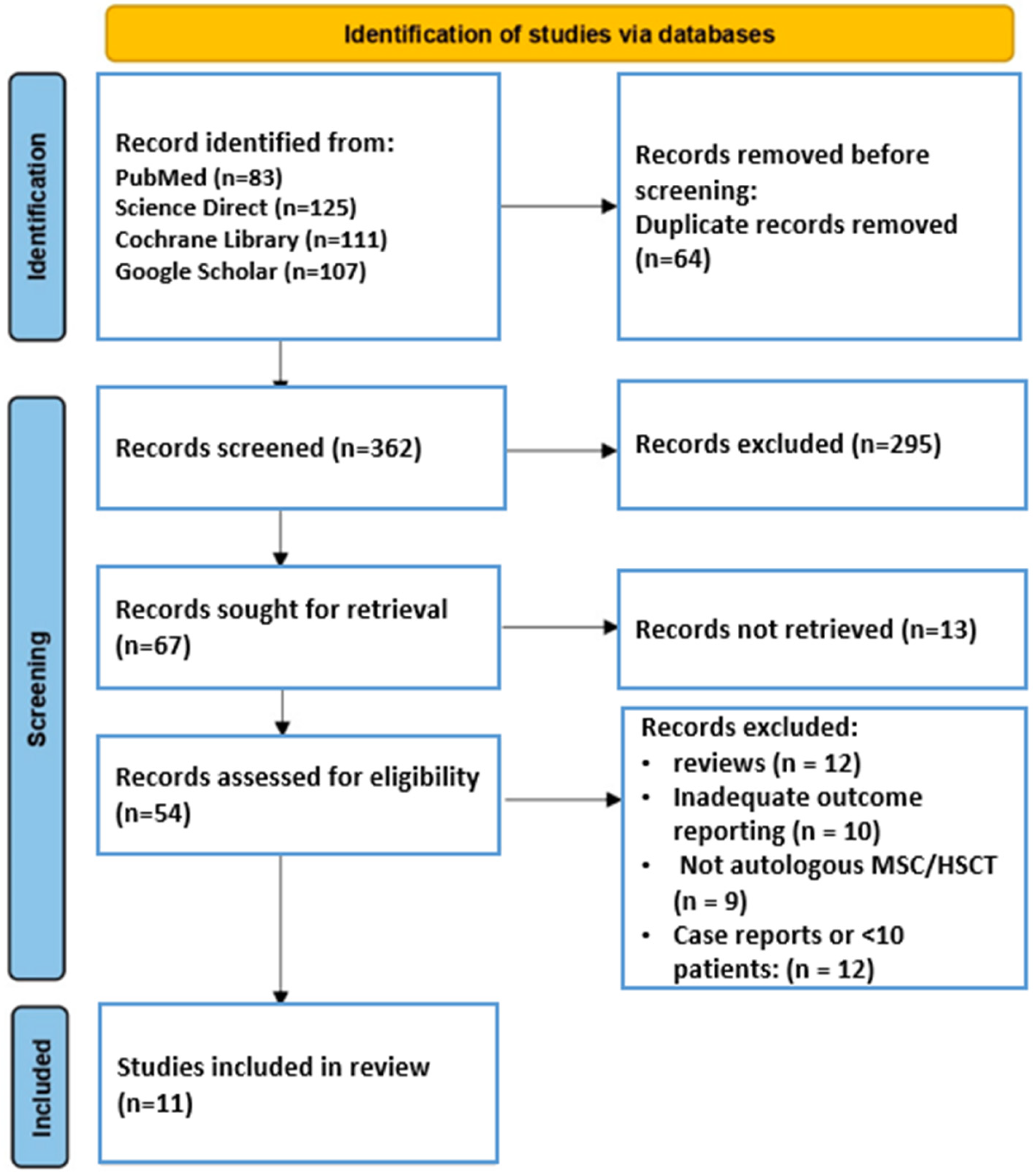

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Selection of Studies and Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias (Quality) Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Included Study Characteristics

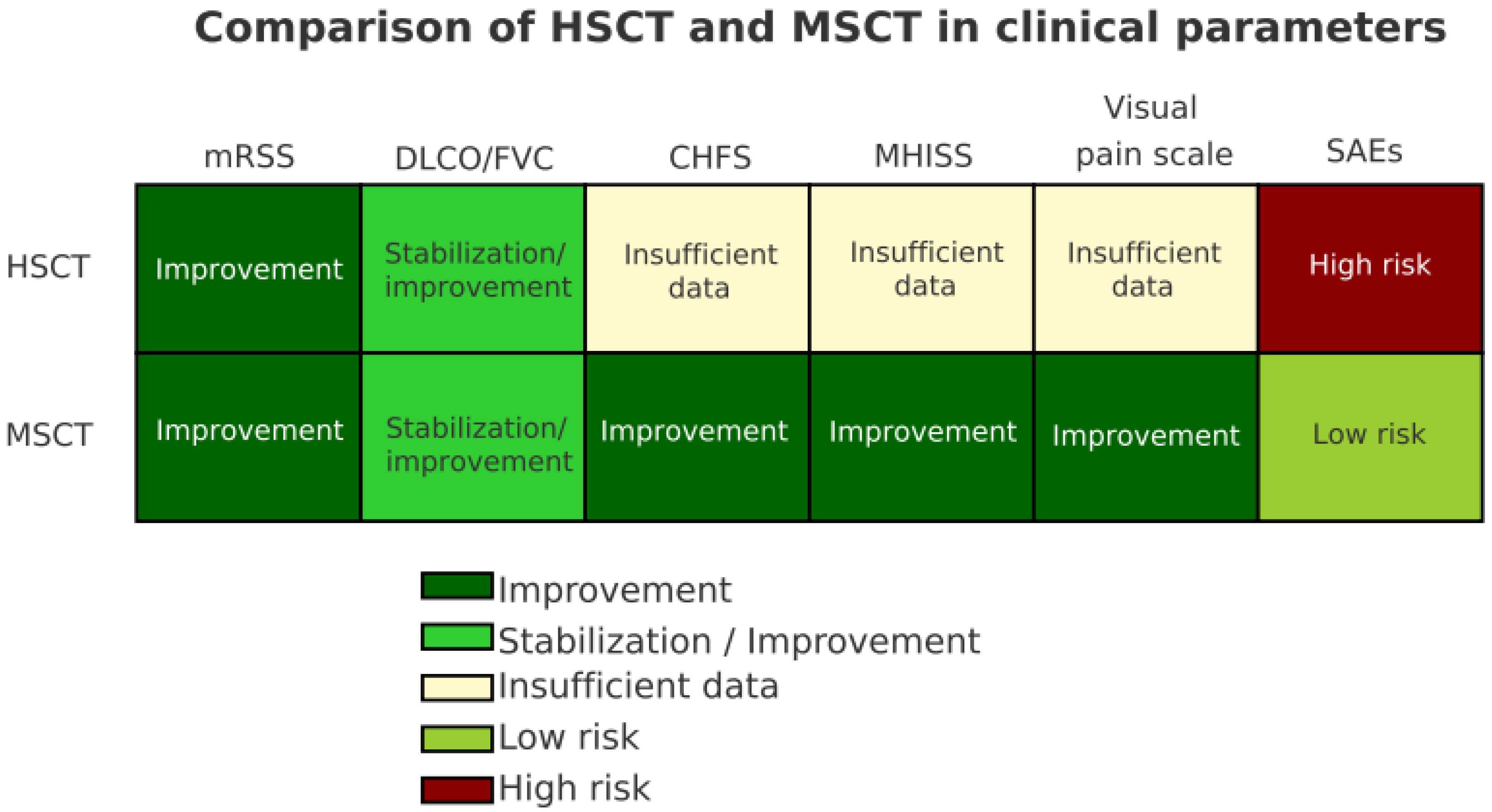

3.2. Clinical Outcomes and Comparison of Cellular Therapy

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Volkmann, E.R.; Andréasson, K.; Smith, V. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 2023, 401, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, J.E.; Denton, C.P.; Johnson, S.R.; Fernandez-Codina, A.; Hudson, M.; Nevskaya, T. State-of-the-art evidence in the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2023, 19, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutka, K.; Garkowski, A.; Karaszewska, K.; Łebkowska, U. Imaging in diagnosis of systemic sclerosis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, Y. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis: An understanding based on a common pathologic cascade across multiple organs and additional organ-specific pathologies. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendahl, A.H.; Schönborn, K.; Krieg, T. Pathophysiology of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2022, 38, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truchetet, M.E.; Brembilla, N.C.; Chizzolini, C. Current concepts on the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 64, 262–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambova, S.N.; Kurteva, E.K.; Dzhambazova, S.S.; Vasilev, G.H.; Kyurkchiev, D.S.; Geneva-Popova, M.G. Capillaroscopy and immunological profile in systemic sclerosis. Life 2022, 12, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Pope, M.; Shen, Y.; Hernandez-Muñoz, J.J.; Wu, L. Prevalence and incidence of systemic sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 22, 2096–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Kang, S.; Zhang, D.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Gui, X.; Yao, X.; Lu, Q. Global, regional, and national incidence and prevalence of systemic sclerosis. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 248, 109267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H. Overall and sex- and disease subtype-specific mortality in patients with systemic sclerosis: An updated meta-analysis. Z. Rheumatol. 2019, 78, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, P. T cell abnormalities in systemic sclerosis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2022, 21, 103185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campochiaro, C.; Allanore, Y. An update on targeted therapies in systemic sclerosis based on a systematic review from the last 3 years. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2021, 23, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcaire-Jones, E.; Low, A.H.L.; Domsic, R.; Whitfield, M.L.; Khanna, D. Advances in biological and targeted therapies for systemic sclerosis. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2023, 23, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keret, S.; Henig, I.; Zuckerman, T.; Kaly, L.; Shouval, A.; Awisat, A.; Rosner, I.; Rozenbaum, M.; Boulman, N.; Dortort Lazar, A.; et al. Outcomes in progressive systemic sclerosis treated with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation compared with combination therapy. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 1534–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana-Gonçalves, M.; Zanin-Silva, D.; Henrique-Neto, Á.; Moraes, D.A.; Kawashima-Vasconcelos, M.Y.; Lima-Junior, J.R.; Dias, J.B.; Bragagnollo, V.; de Azevedo, J.T.; Covas, D.T.; et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation modifies specific aspects of systemic sclerosis-related microvasculopathy. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2022, 14, 1759720X221084845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagnato, G.; Versace, A.G.; La Rosa, D.; De Gaetano, A.; Imbalzano, E.; Chiappalone, M.; Ioppolo, C.; Roberts, W.N.; Bitto, A.; Irrera, N.; et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and systemic sclerosis: Focus on interstitial lung disease. Cells 2022, 11, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Abdallah, N.; Wang, M.; Lansiaux, P.; Puyade, M.; Berthier, S.; Terriou, L.; Charles, C.; Burt, R.K.; Hudson, M.; Farge, D. Long term outcomes of the French ASTIS systemic sclerosis cohort using the global rank composite score. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2021, 56, 2259–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spierings, J.; Nihtyanova, S.I.; Derrett-Smith, E.; Clark, K.E.; van Laar, J.M.; Ong, V.; Denton, C.P. Outcomes linked to eligibility for stem cell transplantation trials in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2022, 61, 1948–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruera, S.; Sidanmat, H.; Molony, D.A.; Mayes, M.D.; Suarez-Almazor, M.E.; Krause, K.; Lopez-Olivo, M.A. Stem cell transplantation for systemic sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 7, CD013693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashitani, K.; Takase-Minegishi, K.; Yoshimi, R.; Kirino, Y.; Hamada, N.; Nagai, H.; Hagihara, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Namkoong, H.; Horita, N.; et al. Benefits and risks of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for systemic sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mod. Rheumatol. 2023, 33, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Ding, Y.; Sun, R.; Jiang, Z.; Li, W.; Su, X.; Tian, R.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, T.; Jiang, J. Mesenchymal stem cells alleviate systemic sclerosis by inhibiting the recruitment of pathogenic macrophages. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanin-Silva, D.C.; Santana-Gonçalves, M.; Kawashima-Vasconcelos, M.Y.; Lima-Júnior, J.R.; Dias, J.B.; Moraes, D.A.; Covas, D.T.; Malmegrim, K.C.; Ramalho, L.; Oliveira, M.C. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation promotes connective tissue remodeling in systemic sclerosis patients. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2022, 24, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.-W.; Kwok, S.-K. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell-Based Therapies in Systemic Rheumatic Disease: From Challenges to New Approaches for Overcoming Restrictions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, D.; Osman, M.S.; Durand, C.; Kim, H.; Hemmati, I.; Jamani, K.; Howlett, J.G.; Johannson, K.A.; Weatherald, J.; Woo, M. Hematopoietic cell transplantation for systemic sclerosis—A review. Cells 2022, 11, 3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Huang, R.; Huang, C.; Nong, G.; Mo, Y.; Ye, L.; Lin, K.; Chen, A. Cell therapy for scleroderma: Progress in mesenchymal stem cells and CAR-T treatment. Front. Med. 2025, 11, 1530887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima-Junior, J.R.; Arruda, L.C.; Goncalves, M.S.; Dias, J.B.; Moraes, D.A.; Covas, D.T.; Simoes, B.P.; Oliveira, M.C.; Malmegrim, K.C. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation restores the suppressive capacity of regulatory B cells in systemic sclerosis patients. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 5538–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Caldron, P.; Martin, R.W.; Kafaja, S.; Spiera, R.; Shahouri, S.; Shah, A.; Hsu, V.; Ervin, J.; Simms, R. Adipose-derived regenerative cell transplantation for the treatment of hand dysfunction in systemic sclerosis: A randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022, 74, 1399–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilkeson, G.S. Safety and efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cells and other cellular therapeutics in rheumatic diseases in 2022: A review of what we know so far. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022, 74, 752–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare Moghaddam, M.; Mousavi, M.J.; Ghotloo, S. Stem cell-based therapy for systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol. Adv. Pract. 2023, 7, rkad101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, E.; Minniti, A.; Alexander, T.; Del Papa, N.; Greco, R.; on behalf of The Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP) of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Cellular-based therapies in systemic sclerosis: From hematopoietic stem cell transplant to innovative approaches. Cells 2022, 11, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Jin, L.; Ding, M.; He, J.; Yang, L.; Cui, S.; Wang, X.; Ma, J.; Liu, A. Efficacy and safety of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of systemic sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar-Soto, C.H.; Mejia-Romero, R.; Aguilera, N.; Alzate-Granados, J.P.; Mendoza-Pinto, C.; Munguia-Realpozo, P.; Mendez-Martinez, S.; Garcia-Carrasco, M.; Rojas-Villarraga, A. Human mesenchymal stem cells for the management of systemic sclerosis. Systematic review. Autoimmun. Rev. 2021, 20, 102831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Rehman, U.; Aslam, F.; Khan, S.; Bhatti, U.; Ramzan, H.; Naveed, F.; Nawaz, J.; Raza, S.M.; Inam, K. Efficacy and safety of mesenchymal stromal cells for steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2025, 21, 1997–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.C.; Elias, J.B.; Moraes, D.A.D.; Simões, B.P.; Rodrigues, M.; Ribeiro, A.A.F.; Piron-Ruiz, L.; Ruiz, M.A.; Hamerschlak, N. A review of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for autoimmune diseases: Multiple sclerosis, systemic sclerosis and Crohn’s disease. Position paper of the Brazilian Society of Bone Marrow Transplantation. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2021, 43, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comparative Efficacy of Autologous Hematopoietic and Mes-enchymal Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251114759 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Sullivan, K.M.; Goldmuntz, E.A.; Keyes-Elstein, L.; McSweeney, P.A.; Pinckney, A.; Welch, B.; Mayes, M.D.; Nash, R.A.; Crofford, L.J.; Eggleston, B.; et al. Myeloablative autologous stem-cell transplantation for severe scleroderma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henes, J.; Oliveira, M.C.; Labopin, M.; Badoglio, M.; Scherer, H.U.; Del Papa, N.; Daikeler, T.; Schmalzing, M.; Schroers, R.; Martin, T.; et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for progressive systemic sclerosis: A prospective non-interventional study from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Autoimmune Disease Working Party. Haematologica 2021, 106, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.-M. Clinical study of autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in the treatment of refractory systemic sclerosis. Asian J. Surg. 2022, 45, 750–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georges, G.E.; Khanna, D.; Wener, M.H.; Mei, M.G.; Mayes, M.D.; Simms, R.W.; Sanchorawala, V.; Hosing, C.; Kafaja, S.; Pawarode, A.; et al. Autologous nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: Identifying disease risk factors for toxicity and long-term outcomes in a prospective, single-arm trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2025, 77, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunz, P.P.; Froehlich, M.; Gernert, M.; Schwaneck, E.C.; Fleischer, A.; Pecher, A.C.; Tony, H.P.; Henes, J.C.; Schmalzing, M. Immunological adverse events after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in systemic sclerosis patients. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 723349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, N.; Schmalzing, M.; Moinzadeh, P.; Oberste, M.; Siegert, E.; Müller-Ladner, U.; Riemekasten, G.; Günther, C.; Kötter, I.; Zeidler, G.; et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation improves long-term survival—Data from a national registry. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2022, 24, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-Pereira, K.R.; Guimarães, A.L.; Moraes, D.A.; Dias, J.B.E.; Garcia, J.T.; de Oliveira-Cardoso, E.A.; Zombrilli, A.; Leopoldo, V.; Costa, T.M.; Simões, B.P.; et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation improves functional outcomes of systemic sclerosis patients. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 26, S131–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alip, M.; Wang, D.; Zhao, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, D.; Duan, X.; Wang, S.; Hua, B.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells transplantation in patients with systemic sclerosis: A 5-year follow-up study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2024, 43, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.; Liu, M.; Yang, D.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cao, X.; Liang, J.; Geng, L.; Zhang, H.; Feng, X.; et al. Improvement in long-term survival with mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in systemic sclerosis patients: A propensity score-matched cohort study. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liang, J.; Tang, X.; Wang, D.; Feng, X.; Wang, F.; Hua, B.; Wang, H.; Sun, L. Sustained benefit from combined plasmapheresis and allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells transplantation therapy in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2017, 19, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farge, D.; Loisel, S.; Resche-Rigon, M.; Lansiaux, P.; Colmegna, I.; Langlais, D.; Charles, C.; Pugnet, G.; Maria, A.T.J.; Chatelus, E.; et al. Safety and preliminary efficacy of allogeneic bone marrow-derived multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells for systemic sclerosis: A single-centre, open-label, dose-escalation, proof-of-concept, phase 1/2 study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2022, 4, e91–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R. Everyday Miracles: Curing Multiple Sclerosis, Scleroderma, and Autoimmune Diseases by Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderstichele, S.; Vranckx, J.J. Anti-fibrotic effect of adipose-derived stem cells on fibrotic scars. World J. Stem Cells 2022, 14, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, Z.; Huang, R.; Yang, G.; Wang, R.; Yang, S.; Guo, L.; Song, Q.; Wei, J.; et al. Advances in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for autoimmune diseases. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, N.; Horio, E.; Sonoda, J.; Yamagishi, M.; Miyakawa, S.; Murakami, F.; Hasegawa, H.; Katahira, Y.; Mizoguchi, I.; Fujii, Y.; et al. Immortalization of mesenchymal stem cells for application in regenerative medicine and their potential risks of tumorigenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, T.; Abasi, M.; Seifar, F.; Eyvazi, S.; Hejazi, M.S.; Tarhriz, V.; Montazersaheb, S. Transplantation of stem cells as a potential therapeutic strategy in neurodegenerative disorders. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 16, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huldani, H.; Jasim, S.A.; Bokov, D.O.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Shalaby, M.N.; Thangavelu, L.; Margiana, R.; Qasim, M.T. Application of extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells as potential therapeutic tools in autoimmune and rheumatic diseases. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 106, 108634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbetta, C.; Bonomi, F.; Lepri, G.; Furst, D.E.; Randone, S.B.; Guiducci, S. Mesenchymal stem-cell-derived exosomes and microRNAs: Advancing cell-free therapy in systemic sclerosis. Cells 2025, 14, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, C.; Müller, F.; Distler, J.H.; Györfi, A.H.; Völkl, S.; Aigner, M.; Kretschmann, S.; Reimann, H.; Harrer, T.; Bayerl, N.; et al. Treatment of a patient with severe systemic sclerosis (SSc) using CD19-targeted CAR T cells. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 1117–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zugmaier, G.; Klinger, M.; Subklewe, M.; Zaman, F.; Locatelli, F. B-cell-depleting immune therapies as potential new treatment options for systemic sclerosis. Sclerosis 2025, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilaki, E.; Mallouri, D.; Batsis, I.; Bousiou, Z.; Vardi, A.; Spyridis, N.; Karavalakis, G.; Panteliadou, A.K.; Dolgyras, P.; Varelas, C.; et al. Safety and long-term efficacy of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for patients with systemic sclerosis. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1527779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campa-Carranza, J.N.; Paez-Mayorga, J.; Chua, C.Y.X.; Nichols, J.E.; Grattoni, A. Emerging local immunomodulatory strategies to circumvent systemic immunosuppression in cell transplantation. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2022, 19, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabizadeh, F.; Pirahesh, K.; Rafiei, N.; Afrashteh, F.; Ahmadabad, M.A.; Zabeti, A.; Mirmosayyeb, O. Autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. Ther. 2022, 11, 1553–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 49th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Physicians—Oral Sessions (O009-O172). Bone Marrow Transpl. 2023, 58, 1002–1085. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, T.; Greco, R. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and cellular therapies for autoimmune diseases: Overview and future considerations from the Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP) of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Bone Marrow Transpl. 2022, 57, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Type of intervention |

|

|

| Cell type |

|

|

| Diagnosis |

|

|

| Type of research |

|

|

| Duration of observation |

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Publication period |

|

|

| Publication language |

|

|

| Full text |

|

|

| No. | Author (Year) | Country | Type of Research | Cell Type | Source of Cells | n Patients/Avg Age | Form of SSD/Observation Period | Key Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sullivan et al. (2018) [38] | USA | RCT, multicenter. | HSC | CD34+ from the periphery | 75 (36 + 39)/ ~45 years | Diffuse with ILD/54–72 months |

|

| 2 | Hennes et al. (2021) [39] | Europe + Brazil | Prospective, multicenter | HSC | CD34+ (at 35/80) | 80/ not specified | Severe dcSSc/ median 24 months |

|

| 3 | Dong (2022) [40] | China | Retrospective | HSC | PBSC | 12/ not specified | dcSSc/ median 12 months |

|

| 4 | Georges et al. (2025) [41] | USA | Prospective, phase 2 | HSC | PBSC (unmodified) | 20/ median 34 years | dcSSc/ median 90 months |

|

| 5 | Strunz et al. (2021) [42] | Germany | Retrospective | HSC | CD34+-selected | 22/ avg. 47.6 years | dcSSc/ median ~48 months |

|

| 6 | Blank et al. (2022) [43] | Germany | National Register | HSC | CD34+-selected | 80/ not specified | 86.3% dcSSc/ up to 180 months |

|

| 7 | Costa Pereira et al. (2020) [44] | Brazil | Longitudinal cohort | HSC | PBSC | 27/ 23.6 years | dcSSc/ 12 months |

|

| 8 | Alip et al. (2024) [45] | China | Retrospective | MSC | Umbilical cord blood | 41/ 18.7 years | Moderate and severe SSD/ 60 months |

|

| 9 | Yuan et al. (2025) [46] | China | Cohort with PSM | MSC | Not specified | 113 (MSC), 220 (control)/ median 47 years | dcSSc/ 120 months |

|

| 10 | Zhang et al. (2017) [47] | China | Interventional | MSC + PF | Allogeneic | 14/ avg. 37.4 years | dcSSc/ avg. 15.6 months |

|

| 11 | Farge et al. (2022) [48] | France | Phase 1/2 | MSC | Donor bone marrow | 20/ 25 years | dcSSc/ 12 months |

|

| No. | Author (Year) | mRSS (Baseline → Follow-Up) | DLCO (%Pred) | FVC (%Pred) | Safety (Key Events) | Survival/EFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sullivan et al. (2018) [38] | 29.7 ± 9.7 → ↓ (GRCS composite) | 53.3 ± 7.9 → composite | 74.1 ± 15.9 → composite | TRM 3% (54 mo), 6% (72 mo); infections, cytopenia | OS 86% vs. 51% (p = 0.02); EFS 79% vs. 50% (p = 0.02) |

| 2 | Henes et al. (2021) [39] | >15 (80%) → ↓ (p < 0.001) | >50% → ↑ (p < 0.001) | >70% → ↑ (p < 0.001) | TRM 6.25% (100 days); cardiotoxicity, CMV | 2-year PFS 81.8%; OS ~90% |

| 3 | Dong et al. (2022) [40] | 2–3 → 0–1 | NR → improved | Restriction in 3 pts → improved | Mucositis, cytopenia; TRM 0 | 1-year OS 100%; PFS 90% |

| 4 | Georges et al. (2025) [41] | Median 34 → ≥50% ↓ (67%) | 62 → ↑ ≥15% (39%) | 76 → ↑ ≥10% (44%) | TRM 10%; SAEs ≥ G3 65%; ICU admission | 5-year OS ~85%; EFS 75%; DEFS 55% |

| 5 | Strunz et al. (2021) [42] | Median 24 → ↓ 60–90% | NR | NR | Engraftment syndrome 41%; secondary autoimmunity 27% | OS not primary endpoint |

| 6 | Blank et al. (2022) [43] | 17.6 ± 11.5 → 11.0 ± 8.5 | 53.9 → stable | NR | TRM 6.3%; SAEs variably reported | 5/10/15-year OS: 96%/92%/86% |

| 7 | Costa Pereira et al. (2020) [44] | 23.6 ± 12.3 → −8.3 (12 mo) | 83.0 → ↓ ~7.7% | 72.9 → stable | Febrile neutropenia 59%; CMV 29%; 1 fatal case | Survival not primary endpoint |

| 8 | Alip et al. (2024) [45] | 18.7 ± 7.3 → 12.4 ± 8.5 (5 yrs) | NR → stable/improved (72% ILD) | NR | No TRM; no severe AEs | Not primary endpoint |

| 9 | Yuan et al. (2025) [46] | Median 13 → ↓ (subgroups) | NR | NR | NR | 10-year OS 89.4% vs. 73.4% (p = 0.002); HR 0.38 |

| 10 | Zhang et al. (2017) [47] | 20.1 ± 3.1 → 13.8 ± 10.2 | NR → improved (3 pts) | NR → improved (3 pts) | URTI (n = 5); no severe AEs | No deaths reported |

| 11 | Farge et al. (2022) [48] | 24.7/26.0 → ↓ (both groups) | 55.2/63.7 → stable | 78.7/72.8 → stable | 36 SAEs; none treatment-related | Clinical response 75%; OS not powered |

| Criterion | HSCT | MSCT | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Survival (1–5–10 years) | 1 year OS 90–100% [38,39,40]; 5 years OS 79–96% [38,39,41,43]; 10 years OS 86–92% [43] | 1 year OS 90–100% [45,46,47]; 5 years OS 73–89% [45,46]; 10 years OS 89% [46] | HSCT has more robust survival data, supported by RCTs and national registries; MSCT evidence mostly observational |

| Skin fibrosis (mRSS) | Significant ↓ in 6/7 studies [38,39,40,41,42,43,44] | Significant ↓ in all 4 studies [45,46,47,48] | Both therapies reduce skin thickening; HSCT shows larger effect sizes but with higher toxicity |

| Pulmonary function (FVC/DLCO) | Improvement or stabilization in 5/7 studies [38,39,40,41,42,43,44] | Improvement or stabilization in 3/4 studies [45,46,47] | HSCT and MSCT both show positive effects on ILD; reporting methods vary (absolute vs. % change) |

| Functional scores (CHFS/HAQ-DI/MHISS/VAS/SF-36) | Rarely reported (1 study, [44]) | Reported in 2 studies [45,47] | MSCT studies tend to capture more patient-reported outcomes, HSCT literature underreports QoL measures |

| Adverse events (SAEs/TRM) | High risk: TRM up to 10% [38,39,40,41,42,43]; infections, cytopenia, cardiotoxicity, amenorrhea | Generally mild: no TRM [45,46,47,48]; mostly infusion reactions or transient symptoms | Safety profile clearly favors MSCT; HSCT requires strict patient selection and monitoring |

| Outcome Measure | HSCT-Reported Range | MSCT-Reported Range | Assessment Methods Used | Notes on Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRSS (skin fibrosis) | Reduction by 8–25 points over 1–5 years [38,39,40,41,42,43,44] | Reduction by 5–12 points over 1–5 years [45,46,47,48] | Modified Rodnan Skin Score (manual palpation, varied number of evaluators) | Significant variability in evaluator training and time-points; cut-offs for “clinically relevant improvement” inconsistent |

| FVC (% predicted) | Stabilization or improvement by +5–15% [38,39,40,41,42,43,44] | Stabilization or improvement by +3–10% [45,46,47,48] | Spirometry (techniques and calibration not always standardized) | Variation in reporting (absolute % vs. relative change) |

| DLCO (% predicted) | +5–20% improvement or stable values [38,39,40,41,42,43,44] | +3–12% improvement or stable values [45,46,47,48] | Single-breath DLCO | Lack of adjustment for hemoglobin |

| Overall survival (OS) | 1-year: 90–100% [38,39,40,41,42,43,44]; 5-year: 79–96% [38,39,41,43]; 10-year: 86–92% [43] | 1-year: 90–100% [45,46,47,48]; 5-year: 73–89% [45,46]; 10-year: up to 89% [46] | Kaplan–Meier analysis, registry follow-up | HSCT supported by RCTs and registries; MSCT mostly retrospective or single-center |

| Event-free survival (EFS/PFS) | 2–5 years: 75–85% [38,39,40,41] | Rarely reported [45,46,47,48] | RCTs, registries | Absence of standardized definition of “event-free survival” across MSCT studies |

| Functional outcomes (CHFS, HAQ-DI, DASH, Raynaud’s index) | Reported in 1–2 studies only [44] | Reported more frequently (hand function, HAQ-DI, Raynaud’s score) [45,46,47,48] | Different scales and patient-reported outcomes | Limited comparability due to inconsistent endpoints |

| Adverse events | TRM up to 10% [38,39,40,41,42,43,44]; infections, amenorrhea, cardiotoxicity [38,39,40,41,42] | Mostly mild; no TRM; occasional transient adverse events [45,46,47,48] | WHO/CTCAE grading inconsistently applied | Strong contrast in safety reporting rigor (more detailed for HSCT, less standardized for MSCT) |

| Characteristic | HSCT | MSCT |

|---|---|---|

| Endorsement by international guidelines | Recommended by EULAR (2017, 2023) and ASBMT [38,39,40,41,42,43] | Not yet endorsed; current evidence insufficient [45,46,47,48] |

| Number of RCTs and systematic reviews | 3 major RCTs [38,41] + ≥5 systematic reviews/meta-analyses | No RCTs; only cohort or phase I/II trials [45,46,47,48] |

| Follow-up duration | Long-term: up to 15 years in registry data [43] | Long-term: up to 10 years in one cohort [46] |

| Study scale | Multicenter prospective trials and national registries [38,39,40,41,42,43] | Mostly single-center, small-scale cohorts [45,46,47,48] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bakirova, S.; Baigenzhin, A.; Tuganbekova, S.; Askarov, M.; Chuvakova, E.; Doskali, M.; Doszhan, A. Comparative Efficacy of Autologous Hematopoietic and Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010261

Bakirova S, Baigenzhin A, Tuganbekova S, Askarov M, Chuvakova E, Doskali M, Doszhan A. Comparative Efficacy of Autologous Hematopoietic and Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):261. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010261

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakirova, Saltanat, Abai Baigenzhin, Saltanat Tuganbekova, Manarbek Askarov, Elmira Chuvakova, Marlen Doskali, and Ainur Doszhan. 2026. "Comparative Efficacy of Autologous Hematopoietic and Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010261

APA StyleBakirova, S., Baigenzhin, A., Tuganbekova, S., Askarov, M., Chuvakova, E., Doskali, M., & Doszhan, A. (2026). Comparative Efficacy of Autologous Hematopoietic and Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010261