Adjusting Iron Markers for Inflammation Reduces Misclassification of Iron Deficiency After Total Hip Arthroplasty

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Study and Design

2.2. Blood Sampling and Biochemical Analysis

2.3. Adjustment for Systemic Inflammation

2.4. Definitions of Iron Deficiency

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

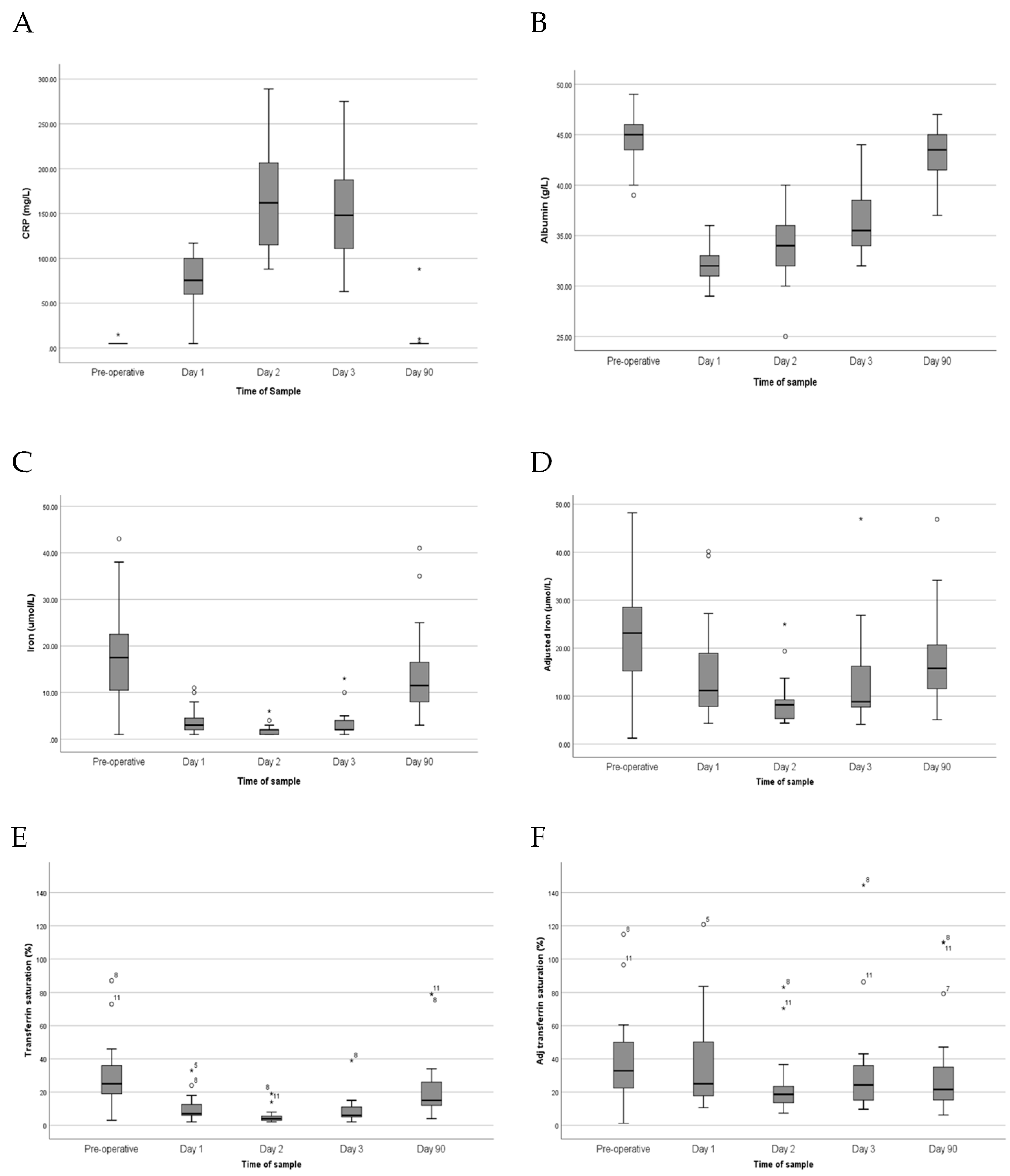

3.2. Systemic Inflammatory Response Following Arthroplasty

3.3. Changes in Iron Parameters

3.4. Reclassification of Iron Deficiency After Adjustment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGP | α-1-acid glycoprotein |

| BRINDA | Biomarkers Reflecting Inflammation and Nutritional Determinants of Anemia |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| EPO | Erythropoietin |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| MCH | Mean corpuscular hemoglobin |

| MCV | Mean corpuscular volume |

| RBC | Red blood cell count |

| TSAT | Transferrin saturation |

References

- Beattie, W.S.; Karkouti, K.; Wijeysundera, D.N.; Tait, G. Risk associated with preoperative anemia in noncardiac surgery: A single-center cohort study. Anesthesiology 2009, 110, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodnough, L.T.; Maniatis, A.; Earnshaw, P.; Benoni, G.; Beris, P.; Bisbe, E.; Fergusson, D.A.; Gombotz, H.; Habler, O.; Monk, T.G.; et al. Detection, evaluation, and management of preoperative anaemia in the elective orthopaedic surgical patient: NATA guidelines. Br. J. Anaesth. 2011, 106, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierbaum, B.E.; Callaghan, J.J.; Galante, J.O.; Rubash, H.E.; Tooms, R.E.; Welch, R.B. An analysis of blood management in patients having a total hip or knee arthroplasty. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. Vol. 1999, 81, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, J.; Muller, M.M.; Lauscher, P.; Sireis, W.; Seifried, E.; Zacharowski, K. Perioperative Red Blood Cell Transfusion: Harmful or Beneficial to the Patient? Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2012, 39, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombotz, H.; Rehak, P.H.; Shander, A.; Hofmann, A. Blood use in elective surgery: The Austrian benchmark study. Transfusion 2007, 47, 1468–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shander, A.; Knight, K.; Thurer, R.; Adamson, J.; Spence, R. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in surgery: A systematic review of the literature. Am. J. Med. 2004, 116 (Suppl. 7), 58s–69s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theusinger, O.M.; Leyvraz, P.F.; Schanz, U.; Seifert, B.; Spahn, D.R. Treatment of iron deficiency anemia in orthopedic surgery with intravenous iron: Efficacy and limits: A prospective study. Anesthesiology 2007, 107, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, J.A.; Bains, S.S.; Hameed, D.; Gottlich, C.; Turpin, R.; Nace, J.; Mont, M.; Delanois, R.E. Projected volume of primary total joint arthroplasty in the USA from 2019 to 2060. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2024, 34, 2663–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubnya, B.G.; Schulz, M.; Váncsa, S.; Szilágyi, G.S.; Szatmári, A.; Bejek, Z. Global Trends in Joint Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Future Projections. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, F.; Moldovan, L. Fixation Methods in Primary Hip Arthroplasty: A Nationwide, Registry-Based Observational Study in Romania (2001–2024). Healthcare 2025, 13, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, M.; Garcia-Erce, J.A.; Cuenca, J.; Bisbe, E.; Naveira, E.; Spanish Anaemia Working Group. On the role of iron therapy for reducing allogeneic blood transfusion in orthopaedic surgery. Blood Transfus. 2012, 10, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSorley, S.T.; Anderson, J.H.; Whittle, T.; Roxburgh, C.S.; Horgan, P.G.; McMillan, D.C.; Steele, C.W. The impact of preoperative systemic inflammation on the efficacy of intravenous iron infusion to correct anaemia prior to surgery for colorectal cancer. Perioper. Med. 2020, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, M.; Acheson, A.G.; Auerbach, M.; Besser, M.; Habler, O.; Kehlet, H.; Liumbruno, G.M.; Lasocki, S.; Meybohm, P.; Rao Baikady, R.; et al. International consensus statement on the peri-operative management of anaemia and iron deficiency. Anaesthesia 2017, 72, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basora, M.; Deulofeu, R.; Salazar, F.; Quinto, L.; Gomar, C. Improved preoperative iron status assessment by soluble transferrin receptor in elderly patients undergoing knee and hip replacement. Clin. Lab. Haematol. 2006, 28, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, E.; McClelland, D.B.L.; Hay, A.; Semple, D.; Walsh, T.S. Prevalence of anaemia before major joint arthroplasty and the potential impact of preoperative investigation and correction on perioperative blood transfusions. BJA Br. J. Anaesth. 2007, 99, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSorley, S.T.; Tham, A.; Steele, C.W.; Dolan, R.D.; Roxburgh, C.S.; Horgan, P.G.; McMillan, D.C. Quantitative data on red cell measures of iron status and their relation to the magnitude of the systemic inflammatory response and survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northrop-Clewes, C.A. Interpreting indicators of iron status during an acute phase response—Lessons from malaria and human immunodeficiency virus. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2008, 45, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.U.; McSorley, S.T.; Patel, P.; Talwar, D. Interpreting iron studies. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 2017, 357, j2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, S.L. Inflammation, dysregulated iron metabolism, and cardiovascular disease. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1124178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E. Iron homeostasis in host defence and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSorley, S.T.; Tham, A.; Jones, I.; Talwar, D.; McMillan, D.C. Regression Correction Equation to Adjust Serum Iron and Ferritin Concentrations Based on C-Reactive Protein and Albumin in Patients Receiving Primary and Secondary Care. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Geng, J.; Zeiler, M.; Nieckula, E.; Sandalinas, F.; Williams, A.; Young, M.F.; Suchdev, P.S. A Practical Guide to Adjust Micronutrient Biomarkers for Inflammation Using the BRINDA Method. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.-B.; Kim, K.-I.; Lee, H.-J.; Yoo, J.-H.; Kim, J.-H. High-Dose Intravenous Iron Supplementation During Hospitalization Improves Hemoglobin Level and Transfusion Rate Following Total Knee or Hip Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Arthroplast. 2025, 40, 1910–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, C.; Wood, P.J.; Archer, T.; Rowe, D.J. Changes in serum ferritin and other ‘acute phase’ proteins following major surgery. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 1984, 21 Pt 4, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aali Rezaie, A.; Blevins, K.; Kuo, F.-C.; Manrique, J.; Restrepo, C.; Parvizi, J. Total Hip Arthroplasty After Prior Acetabular Fracture: Infection Is a Real Concern. J. Arthroplast. 2020, 35, 2619–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, V.D.; Liu, D.; Ngo, D.; Edwards, S. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of universal pre-operative iron studies in total hip and knee arthroplasty. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeler, B.D.; Simpson, J.A.; Ng, O.; Padmanabhan, H.; Brookes, M.J.; Acheson, A.G.; Scholefield, J.; Abercrombie, J.; Robinson, M.; Vitish-Sharma, P.; et al. Randomized clinical trial of preoperative oral versus intravenous iron in anaemic patients with colorectal cancer. BJS Br. J. Surg. 2017, 104, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Reference Interval | Operative Cohort (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | NA | 58 (35–76) |

| Sex (male/female) | NA | 11 (55%)/9 (45%) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | <6 | <6 (<6–<6) |

| Albumin (g/L) | 35–55 | 45 (39–49) |

| Serum Iron (µmol/L) | 10–30 | 17.5 (1.0–43.0) |

| Transferrin (g/L) | 2.0–3.5 | 2.6 (1.9–4.0) |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | 25–45% | 24 (3–73) |

| Albumin (g/L) | CRP (mg/L) | Iron (µmol/L) | Adj. Iron (µmol/L) | Transferrin (g/L) | TSAT (%) | Adj TSAT (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre–operative | 45 (39–49) | <6 (<6–<6) | 17.5 (1.0–43.0) | 23.1 (1.2–54.6) | 2.6 (1.9–4.0) | 25 (3–87) | 33 (1–115) |

| POD 1 | 32 (29–36) | 83 (35–117) | 3.0 (1.0–11.0) | 11.1 (4.3–40.1) | 1.5 (1.0–2.8) | 7 (2–33) | 25 (11–121) |

| POD 2 | 34 (25–40) | 162 (92–289) | 2.0 (1.0–6.0) | 8.2 (4.4–25.0) | 1.6 (1.1–2.8) | 4 (1–39) | 19 (7–83) |

| POD 3 | 36 (32–44) | 148 (63–275) | 2.0 (1.0–13.0) | 8.8 (4.1–46.9) | 1.6 (1.0–2.8) | 6 (2–39) | 24 (10–144) |

| POD 90 | 44 (37–47) | <6 (<6–88) | 11.5 (3.0–41.0) | 15.8 (5.1–54.9) | 2.9 (1.5–4.1) | 15 (4–79) | 22 (6–110) |

| p-values | |||||||

| ANOVA 1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.097 |

| Pre-op/POD1 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.028 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.478 |

| Pre-op/POD2 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| Pre-op/POD90 2 | 0.004 | 0.109 | 0.038 | 0.079 | 0.600 | 0.015 | 0.204 |

| Unadjusted Iron Measurement | Adjusted Iron Measurement | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum iron (µmol/L) | |||

| Preoperative | 17.5 (1.0–43.0) | 23.1 (1.2–54.6) | <0.001 1 |

| Day 1 | 3.0 (1.0–11.0) | 11.1 (4.3–40.1) | <0.001 1 |

| Day 2 | 2.0 (1.0–6.0) | 8.2 (4.4–25.0) | <0.001 1 |

| Day 3 | 2.0 (1.0–13.0) | 8.8 (4.1–46.9) | <0.001 1 |

| Day 90 | 11.5 (3.0–41.0) | 15.8 (5.1–54.9) | <0.001 1 |

| Iron < 10 µmol/L, n (%) | |||

| Preoperative | 3 (15) | 3 (15) | 1.000 2 |

| Day 1 | 18 (90) | 9 (45) | 0.004 2 |

| Day 2 | 20 (100) | 16 (80) | 0.125 2 |

| Day 3 | 18 (90) | 12 (60) | 0.031 2 |

| Day 90 | 8 (40) | 3 (15) | 0.063 2 |

| Unadjusted Iron TSAT Measurement | Adjusted Iron TSAT Measurement | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSAT (%) | |||

| Preoperative | 25 (3–87) | 33 (1–115) | <0.001 1 |

| Day 1 | 7 (2–33) | 25 (11–121) | <0.001 1 |

| Day 2 | 4 (1–39) | 19 (7–83) | <0.001 1 |

| Day 3 | 6 (2–39) | 24 (10–144) | <0.001 1 |

| Day 90 | 15 (4–79) | 22 (6–110) | <0.001 1 |

| TSAT < 20%, n (%) | |||

| Preoperative | 5 (25) | 3 (15) | 0.625 2 |

| Day 1 | 18 (90) | 6 (30) | <0.001 2 |

| Day 2 | 20 (100) | 11 (55) | 0.004 2 |

| Day 3 | 19 (95) | 7 (35) | <0.001 2 |

| Day 90 | 12 (60) | 7 (35) | 0.063 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tham, A.; McMillan, D.C.; Talwar, D.; McSorley, S.T. Adjusting Iron Markers for Inflammation Reduces Misclassification of Iron Deficiency After Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010259

Tham A, McMillan DC, Talwar D, McSorley ST. Adjusting Iron Markers for Inflammation Reduces Misclassification of Iron Deficiency After Total Hip Arthroplasty. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):259. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010259

Chicago/Turabian StyleTham, Alexander, Donald C. McMillan, Dinesh Talwar, and Stephen T. McSorley. 2026. "Adjusting Iron Markers for Inflammation Reduces Misclassification of Iron Deficiency After Total Hip Arthroplasty" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010259

APA StyleTham, A., McMillan, D. C., Talwar, D., & McSorley, S. T. (2026). Adjusting Iron Markers for Inflammation Reduces Misclassification of Iron Deficiency After Total Hip Arthroplasty. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010259