Basal Cell Carcinoma Infiltrating the Facial Bones—Is It Really a Thing of the Past? Personal Experience over 30 Years and a Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role of Imaging in Assessing Bone Infiltration

4.2. Systemic and Adjuvant Treatment Options

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geszti, F.; Hargitai, D.; Lukáts, O.; Győrffy, H.; Tóth, J. Basal cell carcinoma of the periocular region. Pathologe 2013, 34, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, E.; Udkoff, J.; Knackstedt, T. Basal cell carcinoma with bone invasion: A systematic review and pooled survival analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 86, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurse, B. Basal Cell Carcinoma. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482439/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Karki, S.; Parajuli, A.; Bhattarai, B.; Kumari, K.; Harrylal, K.A.; Bhatta, P.; KC, M.; Sharma, S. Neglected Fungating Giant Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Clin. Case Rep. 2024, 12, e8765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Review for the Radiologist. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015, 204, W1–W17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhail, G.R.; Boulos, R.S.; Knighton, R.S.; Rogers, J.S.; Malik, G.; Ditmars, D.M.; Nichols, R.D. Cranial Invasion by Basal Cell Carcinoma. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 1986, 12, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.B.; Walton, S.; Keczkes, K. Extensive and Fatal Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Report of Three Cases. Br. J. Dermatol. 1992, 127, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagler, R.M.; Laufer, D. Invading Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Jaw: An Under-Evaluated Complex Entity. Anticancer Res. 2001, 21, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aygit, C.; Top, H.; Bilgi, S.; Ozbey, B. Invading Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Bone: Diagnosis and Treatment Approaches. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 64, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, D.; Fortin, D. Intracranial Invasion of a Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Scalp. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2005, 32, 546–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibovitch, I.; McNab, A.; Sullivan, T.; Davis, G.; Selva, D. Orbital invasion by periocular basal cell carcinoma. Ophthalmology 2005, 112, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleydman, Y.; Manolidis, S.; Ratner, D. Basal Cell Carcinoma with Intracranial Invasion. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2009, 60, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffary, P.M.; Delavarian, Z.; Amirchaghmaghi, M.; Dalirsani, Z.; Mostaan, L.V.; Khadem, S.S.; Ghalavani, H. Secondary Involvement of the Mandible due to Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Case Report. Iran J. Med. Sci. 2015, 40, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bengoa-González, A.; Mencía-Gutiérrez, E.; Garrido, M.; Salvador, E.; Lago-Llinás, M.D. Advanced Periocular Basal Cell Carcinoma with Orbital Invasion: Update on Management and Treatment Advances. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 2024, 4347707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cameron, M.C.; Lee, E.; Hibler, B.P.; Barker, C.A.; Mori, S.; Cordova, M.; Nehal, K.S.; Rossi, A.M. Basal cell carcinoma: Epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzig, T.; Stroux, A.; Simon, J.C.; Paasch, U. Anatomical site as a prognostic factor in high-risk basal cell carcinoma. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015, 29, 279–282. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, J.D.; Davie, R.M. The significance of incomplete excision in patients with basal cell carcinoma. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1987, 40, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, A.D.; Milenković, V.; Petrovic, M.; Tomic, A.; Matejic, A.; Brkic, N.; Jovanović, M. Infiltrative Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Head: Factors Influencing Bone Invasion and Surgical Outcomes. Life 2025, 15, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, A.B.; Tahan, S.R.; Goldberg, L.H. The use of imaging studies in the management of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol. Surg. 2010, 36, 1629–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparrotti, F.; Troussier, I.; Ali, A.; Zilli, T. Localized Non-melanoma Skin Cancer: Risk Factors of Post-surgical Relapse and Role of Postoperative Radiotherapy. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2020, 21, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulic, A.; Migden, M.R.; Oro, A.E.; Dirix, L.; Lewis, K.D.; Hainsworth, J.D.; Solomon, J.A.; Yoo, S.; Arron, S.T.; Friedlander, P.A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Vismodegib in Advanced Basal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2171–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migden, M.R.; Guminski, A.; Gutzmer, R.; Lear, J.T.; Lewis, K.D.; Chang, A.L.S.; Combemale, P.; Stratigos, A.J.; Plummer, R.; Seebode, C.; et al. Treatment with Two Different Doses of Sonidegib in Patients with Locally Advanced or Metastatic Basal Cell Carcinoma (BOLT): A Multicentre, Randomised, Double-Blind Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigos, A.J.; Sekulic, A.; Peris, K.; Bechter, O.; Dummer, R.; Lewis, K.; Carlino, M.S.; Licitra, L.; Queirolo, P.; Ascierto, P.A.; et al. Cemiplimab in Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma After Hedgehog Inhibitor Therapy: Results from an International, Open-Label, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzeciak, M.; Ziętek, M.; Adamski, Z. Evaluation of the tolerability of Hedgehog pathway inhibitors. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2024, 25, 323–335. [Google Scholar]

| No. of Case | Sex | Age | Site of BCC | Previous Treatment | Diameter of BCC [mm] | Type of Surgical Therapy for BCC | Year of Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

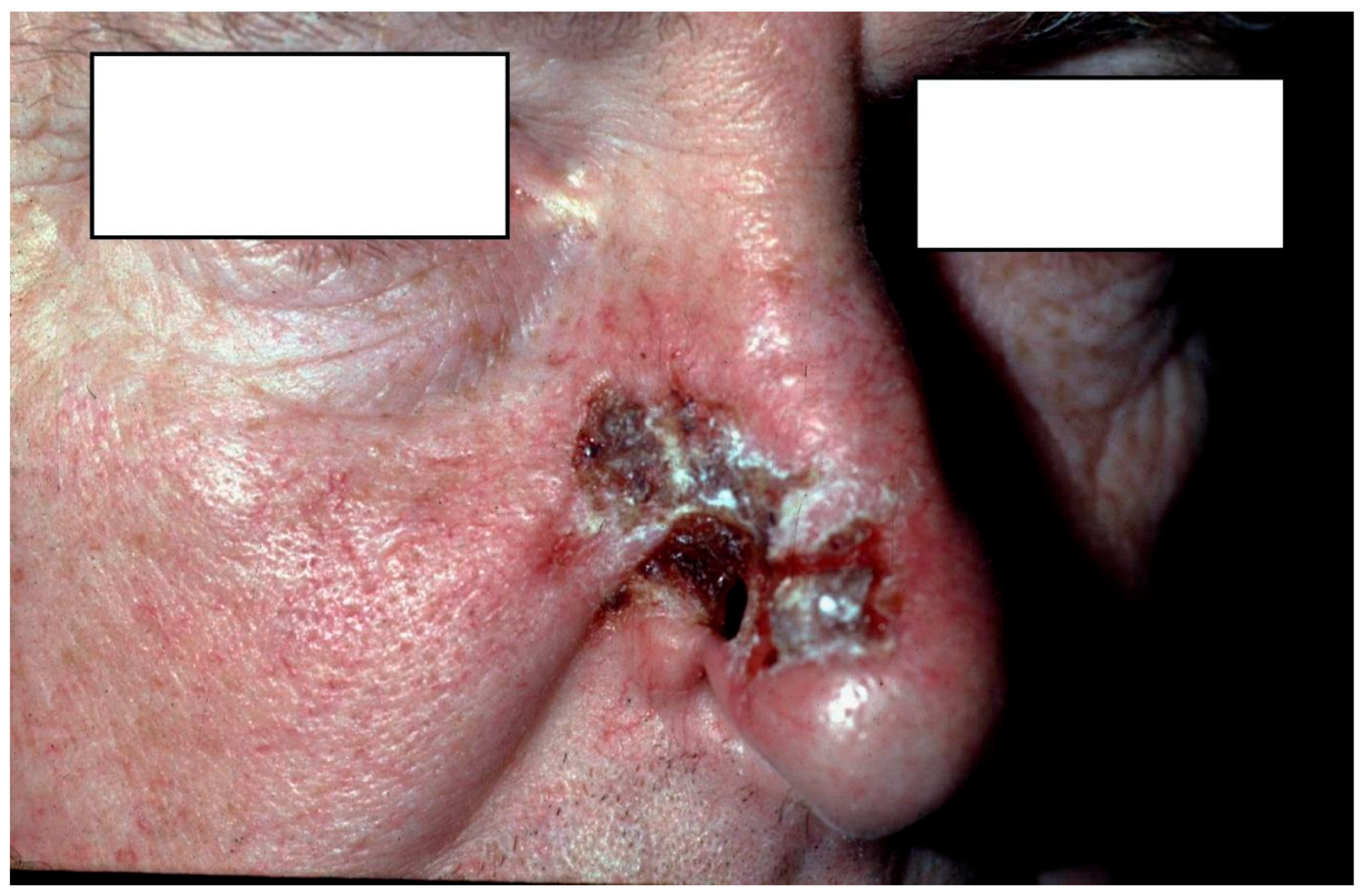

| 1 (Figure 1) | M | 68 | Nose (nasal bone) | no | 30 | Local flap | 1994 |

| 2 | M | 76 | Nose (nasal bone) | yes | 30 | Local flap | 1994 |

| 3 | M | 74 | Nose (nasal bone) | no | 25 | Local flap | 1996 |

| 4 | M | 76 | Nose (nasal bone) | no | 28 | Local flap | 1998 |

| 5 | K | 86 | Temple (temporal bone) | no | 55 | Skin graft | 1998 |

| 6 (Figure 2) | K | 53 | Nose (nasal bone) | no | 25 | Local flap | 2001 |

| 7 | K | 85 | Forehead (frontal bone) | no | 50 | Skin graft | 2007 |

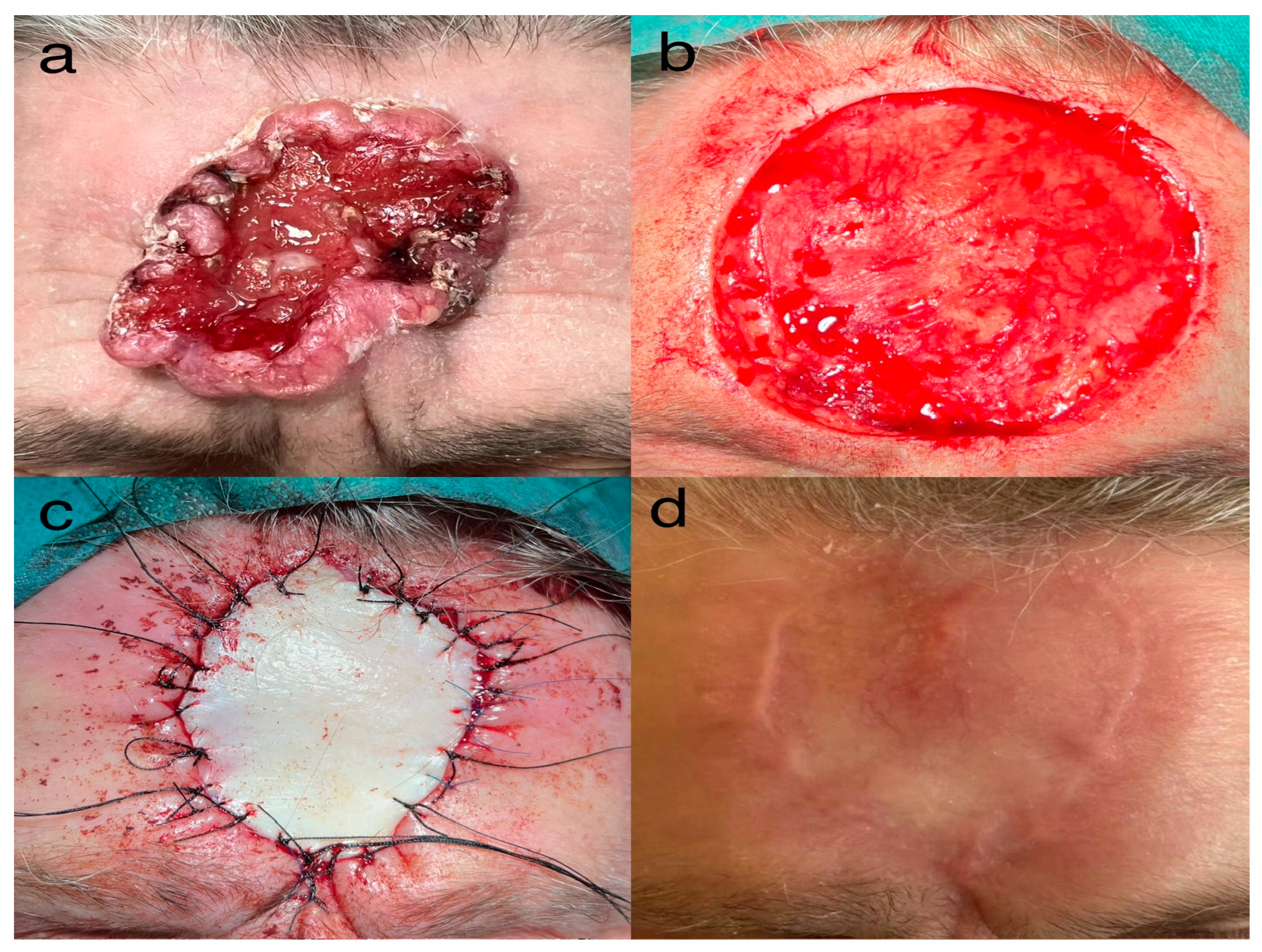

| 8 (Figure 3) | K | 84 | Forehead (frontal bone) | yes | 68 | Skin graft | 2025 |

| No. | Sex | Age | Site of BCC | Previous Treatment | Diameter of BCC [mm] | Type of Surgical Therapy for BCC | Year of Treatment | Time to Intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mikhail et al., 1986 [6] | F | 78 | forehead/scalp | Yes | large | Mohs, flaps | 1986 | - |

| 2 | Mikhail et al., 1986 [6] | M | 54 | temple/zygomatic/orbit | - | large | Mohs | 1986 | - |

| 3 | Mikhail et al., 1986 [6] | F | 60 | orbit/ethmoid | Yes | - | Mohs, grafts | 1986 | ~20 years |

| 4 | Ko et al., 1992 [7] | M | 61 | right face/dura | No | 170 × 120 | None (palliative) | 1992 | 6 years |

| 5 | Ko et al., 1992 [7] | F | 70 | scalp/forehead/nose | No | 200 × 150 | Radiotherapy + excision + grafts | 1992 | 7 years |

| 6 | Ko et al., 1992 [7] | F | 82 | glabella/nose/eyelids | No | large | Graft + radiotherapy | 1992 | 15 years |

| 7 | Nagler and Laufer, 2001 [8] | None | None | mandible/maxilla (3 cases) | None | None | mandibular/maxilla resection | nan | None |

| 8 | Aygit et al., 2006 [9] | M | 61 | oral commissure/mandible | Yes | 30 × 30 | Mandibular resection + flap | nan | ~10 years |

| 9 | Aygit et al., 2006 [9] | M | 65 | orbit/maxilla | Yes | 20 × 20 | Bone graft + free flap | nan | ~3 years |

| 10 | Aygit et al., 2006 [9] | F | 70 | nasal dorsum | No | 15 × 15 | Flaps | nan | ~20 years |

| 11 | Aygit et al., 2006 [9] | M | 65 | maxilla | No | 25 × 10 | Implant + flap | nan | ~10 years |

| 12 | Aygit et al., 2006 [9] | F | 67 | orbit/zygomatic | No | 60 × 60 | Palliative | nan | None |

| 13 | Mathieu and Fortin, 2005 [10] | F | 66 | forehead | Yes | 80 × 80 | frontal one resection flap, cranioplasty | 2005 | 5 years |

| 14 | Leibovitch et al., 2005 [11] | None | 70 ± 13 | orbit (64 cases) | 84% recurrent | - | Orbital exenteration | 2005 | 3.5–7.8 years |

| 15 | Kleydman et al., 2009 [12] | F | 87 | nose → calvarium | Yes | 7 × 5 | Flap | 2008 | 7 years |

| 16 | Kleydman et al., 2009 [12] | F | 87 | nose → cranial nerves | Yes | 7 × 5 | Flap + RT | 2009 | 6 years |

| 17 | Mozaffary et al., 2015 [13] | F | 50 | chin/mandible | No | 90 × 55 | Flap | 2015 | 20 years |

| 18 | Russell et al., 2022 [2] | None | None | (101 cases) | - | - | - | 2022 | - |

| 19 | Bengoa-González et al., 2024 [14] | None | None | orbit (7 cases) | 84% recurrent | - | Exenteration ± vismodegib | 2011–2023 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kozinska, U.; Chlebicka, I.; Knecht-Gurwin, K.; Bieniek, A.; Majda, F.; Szepietowski, J.C. Basal Cell Carcinoma Infiltrating the Facial Bones—Is It Really a Thing of the Past? Personal Experience over 30 Years and a Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010254

Kozinska U, Chlebicka I, Knecht-Gurwin K, Bieniek A, Majda F, Szepietowski JC. Basal Cell Carcinoma Infiltrating the Facial Bones—Is It Really a Thing of the Past? Personal Experience over 30 Years and a Review of the Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):254. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010254

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozinska, Urszula, Iwona Chlebicka, Klaudia Knecht-Gurwin, Andrzej Bieniek, Filip Majda, and Jacek C. Szepietowski. 2026. "Basal Cell Carcinoma Infiltrating the Facial Bones—Is It Really a Thing of the Past? Personal Experience over 30 Years and a Review of the Literature" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010254

APA StyleKozinska, U., Chlebicka, I., Knecht-Gurwin, K., Bieniek, A., Majda, F., & Szepietowski, J. C. (2026). Basal Cell Carcinoma Infiltrating the Facial Bones—Is It Really a Thing of the Past? Personal Experience over 30 Years and a Review of the Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010254