Prevalence and Impact of Urinary Incontinence at 5–10 Years After a Singleton Birth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

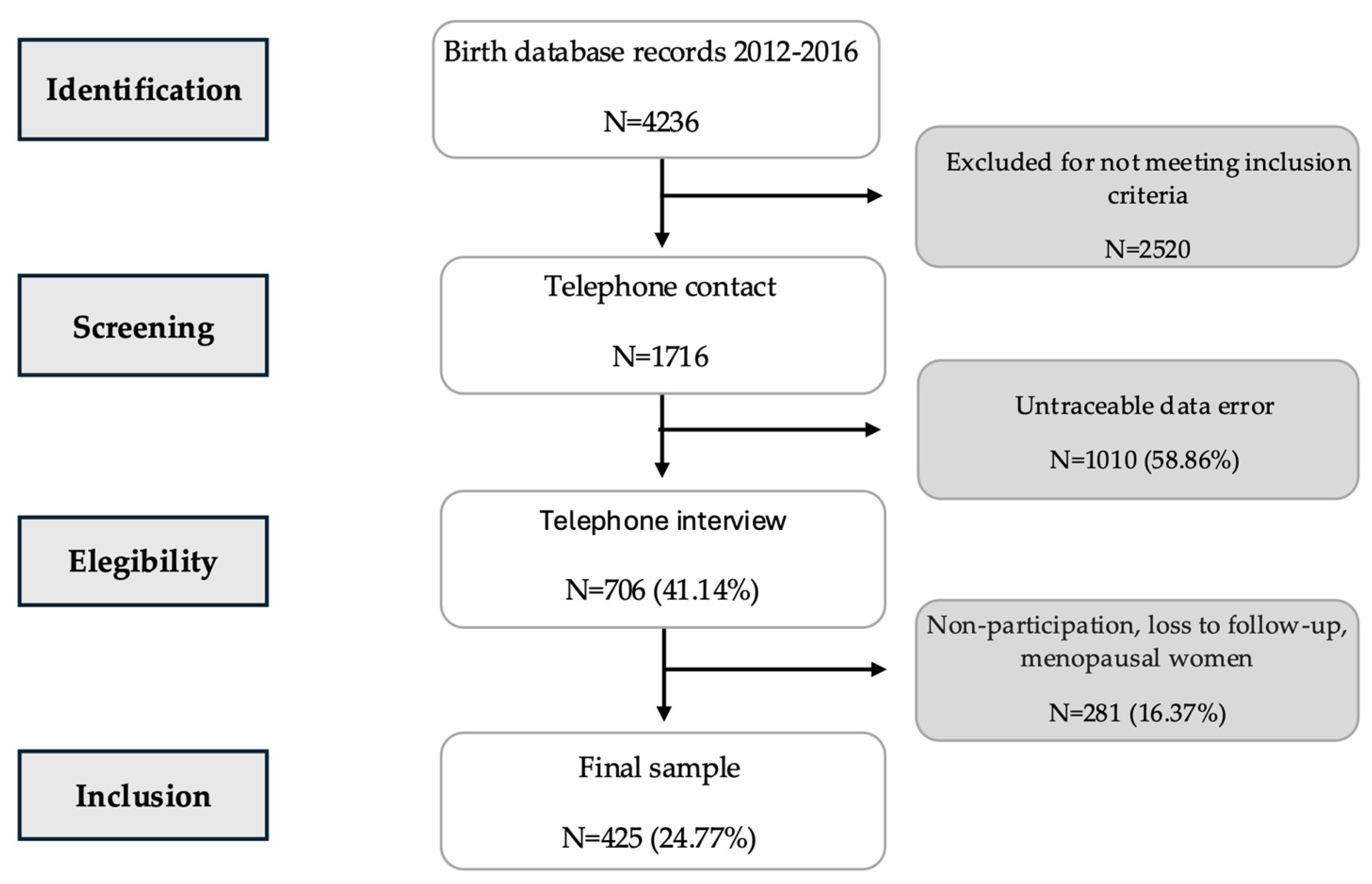

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Variables and Operational Definitions

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.1.1. Sociodemographic and Health Variables

3.1.2. Obstetric and Perinatal Variables

3.1.3. Logistic Regression

3.2. Urinary Incontinence Assessment

3.2.1. ICIQ-UI-SF

3.2.2. Women’s Perception

4. Discussion

- (a)

- Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) during early pregnancy has been shown to have positive effects on continence capacity postpartum [63].

- (b)

- Cesarean delivery appears to have a protective effect on female pelvic floor dysfunctions, including UI. The Cochrane Review by Lavender et al. (2012) examined this issue as a long-term secondary maternal outcome and concluded that there is no evidence from randomized controlled trials to support elective cesarean section for non-medical reasons at term [64].

- (c)

- Preventive measures, including weight control, dietary modifications (avoiding excessive fluid intake and consumption of caffeine or tea), and management of comorbid or contributing conditions (e.g., chronic diseases or related treatments), may help reduce UI risk. Lifestyle modifications and bladder training may also be beneficial for certain UI types [65].

- (d)

- In general, universal screening for UI in asymptomatic women is not recommended due to insufficient evidence regarding its effectiveness and potential harms. However, opportunistic screening in primary care has been proposed in Spain [66] by scientific societies (SEMERGEN, SEMG, and semFYC) for asymptomatic women over 40 years of age. In line with our results, targeted screening may be useful in selected groups of women to facilitate preventive interventions.

- (e)

- Finally, there is high certainty evidence that pelvic floor muscle training can cure symptoms and improve quality of life across all UI types [65].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aOR | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| ICIQ-UI-SF | International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Urinary Incontinence Short Form |

| ICS | International Continence Society |

| IUGA | International Urogynecological Association |

| KHQ | King’s Health Questionnaire |

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| MUI | Mixed Urinary Incontinence |

| PFDs | Pelvic Floor Disorders |

| SEMERGEN | Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians |

| SEMG | Spanish Society of General and Family Physicians |

| semFYC | Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine |

| SUI | Stress Urinary Incontinence |

| UI | Urinary Incontinence |

| UUI | Urgency Urinary Incontinence |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Abrams, P.; Cardozo, L.; Fall, M.; Griffiths, D.; Rosier, P.; Ulmsten, U.; Van Kerrebroeck, P.; Victor, A.; Wein, A. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: Report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology 2003, 61, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haylen, B.T.; de Ridder, D.; Freeman, R.M.; Swift, S.E.; Berghmans, B.; Lee, J.; Monga, A.; Petri, E.; Rizk, D.E.; Sand, P.K.; et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2010, 21, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subak, L.L.; Brown, J.S.; Kraus, S.R.; Brubaker, L.; Lin, F.; Richter, H.E.; Bradley, C.S.; Grady, D. The “costs” of urinary incontinence for women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 908–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Córcoles, B.M.; Sánchez, A.S.; Bachs, J.G.; Moreno, M.D.; Navarro, H.P.; Rodríguez, J.V. Calidad de vida en las pacientes con incontinencia urinaria [Quality of life in patients with urinary incontinence]. Actas Urol. Esp. 2008, 32, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minassian, V.A.; Devore, E.; Hagan, K.; Grodstein, F. Severity of urinary incontinence and effect on quality of life in women by incontinence type. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 121, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, C.; Espuña-Pons, M.; Ortega, J.A.; Aliaga, F.; Pérez-González y GRESP (Grup de Recerca Sòl Pelvià). Urinary incontinence in gynaecological consultations. Do all women with symptoms wish to be treated? Actas Urol. Esp. 2015, 39, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerruto, M.A.; D’Elia, C.; Aloisi, A.; Fabrello, M.; Artibani, W. Prevalence, incidence and obstetric factors’ impact on female urinary incontinence in Europe: A systematic review. Urol. Int. 2013, 90, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantoushzadeh, S.; Javadian, P.; Shariat, M.; Salmanian, B.; Ghazizadeh, S.; Aghssa, M. Stress urinary incontinence: Pre-pregnancy history and effects of mode of delivery on its postpartum persistency. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2011, 22, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokabi, R.; Yazdanpanah, D. Effects of delivery mode and sociodemographic factors on postpartum stress urinary incontinency in primipara women: A prospective cohort study. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2017, 80, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannestad, Y.S.; Rortveit, G.; Sandvik, H.; Hunskaar, S. Epidemiology of Incontinence in the County of Nord-Trøndelag. A community-based epidemiological survey of female urinary incontinence: The Norwegian EPINCONT study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2000, 53, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, D.B.; Praça, N.S. Incontinência urinária autorreferida no pós-parto: Características clínicas [Self-reported urinary incontinence in the postpartum period: Clinical characteristics]. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2012, 46, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrue Gabilondo, M.; Ginto, L.; Zubikarai, M.; Galán, C.; Saro, J.; Diez-Itza, I. Risk factors associated with stress urinary incontinence 12 years after first delivery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021, 32, 3061–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delancey, J.O.; Kane Low, L.; Miller, J.M.; Patel, D.A.; Tumbarello, J.A. Graphic integration of causal factors of pelvic floor disorders: An integrated life span model. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 199, 610.e1–610.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumouchtsis, S.K.; de Tayrac, R.; Lee, J.; Daly, O.; Melendez-Munoz, J.; Lindo, F.M.; Cross, A.; White, A.; Cichowski, S.; Falconi, G.; et al. An International Continence Society (ICS)/International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) joint report on the terminology for the assessment and management of obstetric pelvic floor disorders. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2023, 34, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, C.K.; Lapitan, M.C.; Arlandis, S.; Bø, K.; Cobussen-Boekhorst, H.; Costantini, E.; Groen, J.; Nambiar, A.K.; Omar, M.I.; Peyronnet, B.; et al. EAU Guidelines on Management of Non-Neurogenic Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Eur. Assoc. Urol. 2023, 82, 60–70. Available online: https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Non-neurogenic-Female-LUTS-2023.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- MacLennan, A.H.; Taylor, A.W.; Wilson, D.H.; Wilson, D. The prevalence of pelvic floor disorders and their relationship to gender, age, parity and mode of delivery. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2000, 107, 1460–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritel, X.; Ringa, V.; Varnoux, N.; Fauconnier, A.; Piault, S.; Bréart, G. Mode of delivery and severe stress incontinence: A cross-sectional study among 2625 perimenopausal women. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2005, 112, 1646–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbesen, M.H.; Hunskaar, S.; Rortveit, G.; Hannestad, Y.S. Prevalence, incidence and remission of urinary incontinence in women: Longitudinal data from the Norwegian HUNT study (EPINCONT). BMC Urol. 2013, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber Pedersen, L.; Lose, G.; Høybye, M.T.; Elsner, S.; Waldmann, A.; Rudnicki, M. Prevalence of urinary incontinence among women and analysis of potential risk factors in Germany and Denmark. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2017, 96, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rortveit, G.; Daltveit, A.K.; Hannestad, Y.S.; Hunskaar, S. Urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery or cesarean section. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foldspang, A.; Hvidman, L.; Mommsen, S.; Nielsen, J.B. Risk of postpartum urinary incontinence associated with pregnancy and mode of delivery. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2004, 83, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritel, X.; Fauconnier, A.; Levet, C.; Bénifla, J.L. Stress urinary incontinence 4 years after the first delivery: A retrospective cohort survey. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2004, 83, 941–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, D.H.; Rortveit, G. Prevalence of postpartum urinary incontinence: A systematic review. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2010, 89, 1511–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, M.H.; Franzén, K.; Tegerstedt, G.; Hiyoshi, A.; Nilsson, K. Stress and urgency urinary incontinence one year after a first birth—Prevalence and risk factors: A prospective cohort study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 2193–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viktrup, L. The risk of lower urinary tract symptoms five years after the first delivery. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2002, 21, 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porena, M.; Costantini, E.; Lazzeri, M. Mixed Incontinence: How Best to Manage It? Curr. Bladder Dysfunct. Rep. 2013, 8, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, X.; Zuo, Y.; Li, X. Risk factors of postpartum stress urinary incontinence in primiparas: What should we care. Medicine 2021, 100, e25796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyhagen, M.; Bullarbo, M.; Nielsen, T.F.; Milsom, I. The prevalence of urinary incontinence 20 years after childbirth: A national cohort study in singleton primiparae after vaginal or caesarean delivery. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013, 120, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzoferrato, A.C.; Briant, A.R.; Le Grand, C.; Gaichies, L.; Fauvet, R.; Fauconnier, A.; Fritel, X. Influence of prenatal urinary incontinence and mode of delivery in postnatal urinary incontinence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 52, 102536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.J.; Gartland, D.; Donath, S.; MacArthur, C. Effects of prolonged second stage, method of birth, timing of caesarean section and other obstetric risk factors on postnatal urinary incontinence: An Australian nulliparous cohort study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 118, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, J.A.; Bravo, C.; Pintado-Recarte, M.P.; Asúnsolo, Á.; Cueto-Hernández, I.; Ruiz-Labarta, J.; Buján, J.; Ortega, M.A.; De León-Luis, J.A. Pelvic floor morbidity following vaginal delivery versus cesarean delivery: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INE-Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Movimiento Natural de la Población/Indicadores Demográficos Básicos. Ine.es 2024. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/Prensa/es/MNP2023.htm?print=1 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Bedretdinova, D.; Fritel, X.; Panjo, H.; Ringa, V. Prevalence of female urinary incontinence in the general population according to different definitions and study designs. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas Casado, J.; Díaz Rodríguez, A.; Brenes Bermúdez, F.; Cuenllas Díaz, A.; Verdejo Bravo, C. Prevalencia de la Incontinencia Urinaria en España. Urod. A 2010, 23, 52–66. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261251887 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Pena Outeiriño, J.M.; Rodríguez Pérez, A.J.; Villodres Duarte, A.; Mármol Navarro, S.; Lozano Blasco, J.M. Tratamiento de la disfunción del suelo pélvico [Treatment of the dysfunction of the pelvic floor]. Actas Urol. Esp. 2007, 31, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Timoneda, A.; Valles-Murcia, N.; Muñoz Esteban, P.; Torres López, M.S.; Turrión Martínez, E.; Errandonea Garcia, P.; Serrano Raya, L.; Nohales Alfonso, F. Prevalence and impact of pelvic floor dysfunctions on quality of life in women 5–10 years after their first vaginal or caesarian delivery. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, K.; Donovan, J.; Peters, T.J.; Shaw, C.; Gotoh, M.; Abrams, P. ICIQ: A brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2004, 23, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obesidad y Sobrepeso. Who.int. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Khowailed, I.A.; Pinjuv-Turney, J.; Lu, C.; Lee, H. Stress incontinence during different high-impact exercises in women: A pilot survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, B.E.; Haskell, W.L.; Herrmann, S.D.; Meckes, N.; Bassett, D.R., Jr.; Tudor-Locke, C.; Greer, J.L.; Vezina, J.; Whitt-Glover, M.C.; Leon, A.S. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: A second update of codes and MET values. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1575–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espuña Pons, M.; Rebollo Alvarez, P.; Puig Clota, M. Validación de la versión española del International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form. Un cuestionario para evaluar la incontinencia urinaria [Validation of the Spanish version of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form. A questionnaire for assessing urinary incontinence]. Med. Clin. 2004, 122, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klovning, A.; Avery, K.; Sandvik, H.; Hunskaar, S. Comparison of two questionnaires for assessing the severity of urinary incontinence: The ICIQ-UI SF versus the incontinence severity index. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2009, 28, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.M.; Vaughan, C.P.; Goode, P.S.; Redden, D.T.; Burgio, K.L.; Richter, H.E.; Markland, A.D. Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, I.; Barber, M.D.; Burgio, K.L.; Kenton, K.; Meikle, S.; Schaffer, J.; Spino, C.; Whitehead, W.E.; Wu, J.; Brody, D.J.; et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA 2008, 300, 1311–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, H.P.; Bennett, M.J. The effect of childbirth on pelvic organ mobility. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 102, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLancey, J.O.; Kearney, R.; Chou, Q.; Speights, S.; Binno, S. The appearance of levator ani muscle abnormalities in magnetic resonance images after vaginal delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 101, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, A.H.; Kamm, M.A.; Hudson, C.N. Pudendal nerve damage during labour: Prospective study before and after childbirth. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1994, 101, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viktrup, L.; Rortveit, G.; Lose, G. Risk of stress urinary incontinence twelve years after the first pregnancy and delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 108, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tähtinen, R.M.; Cartwright, R.; Tsui, J.F.; Aaltonen, R.L.; Aoki, Y.; Cárdenas, J.L.; El Dib, R.; Joronen, K.M.; Al Juaid, S.; Kalantan, S.; et al. Long-term impact of mode of delivery on stress urinary incontinence and urgency urinary incontinence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keag, O.E.; Norman, J.E.; Stock, S.J. Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.J.; Sun, Y. Comparison of caesarean section and vaginal delivery for pelvic floor function of parturients: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 235, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage-Fransen, M.A.H.; Wiezer, M.; Otto, A.; Wieffer-Platvoet, M.S.; Slotman, M.H.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.G.; Pool-Goudzwaard, A.L. Pregnancy- and obstetric-related risk factors for urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, or pelvic organ prolapse later in life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khullar, V.; Sexton, C.C.; Thompson, C.L.; Milsom, I.; Bitoun, C.E.; Coyne, K.S. The relationship between BMI and urinary incontinence subgroups: Results from EpiLUTS. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2014, 33, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, S.; Yao, Y. Association between obesity and urinary incontinence in older adults from multiple nationwide longitudinal cohorts. Commun. Med. 2023, 3, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushkat, Y.; Bukovsky, I.; Langer, R. Female urinary stress incontinence—Does it have familial prevalence? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 174, 617–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannestad, Y.S.; Lie, R.T.; Rortveit, G.; Hunskaar, S. Familial risk of urinary incontinence in women: Population-based cross-sectional study. BMJ 2004, 329, 889–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isali, I.; Mahran, A.; Khalifa, A.O.; Sheyn, D.; Neudecker, M.; Qureshi, A.; Conroy, B.; Schumacher, F.R.; Hijaz, A.K.; El-Nashar, S.A. Gene expression in stress urinary incontinence: A systematic review. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbesen, M.H.; Hannestad, Y.S.; Midthjell, K.; Hunskaar, S. Diabetes and urinary incontinence–prevalence data from Norway. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2007, 86, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunzunegui Pastor, M.V.; Rodríguez-Laso, A.; García de Yébenes, M.J.; Aguilar Conesa, M.D.; Lázaro y de Mercado, P.; Otero Puime, A. Prevalencia de la incontinencia urinaria y factores asociados en varones y mujeres de más de 65 años [Prevalence of urinary incontinence and linked factors in men and women over 65]. Aten. Primaria 2003, 32, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solans-Domènech, M.; Sánchez, E.; Espuña-Pons, M.; Pelvic Floor Research Group (Grup de Recerca del Sòl Pelvià; GRESP). Urinary and anal incontinence during pregnancy and postpartum: Incidence, severity, and risk factors. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 115, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monz, B.; Chartier-Kastler, E.; Hampel, C.; Samsioe, G.; Hunskaar, S.; Espuña-Pons, M.; Wagg, A.; Quail, D.; Castro, R.; Chinn, C. Patient characteristics associated with quality of life in European women seeking treatment for urinary incontinence: Results from PURE. Eur. Urol. 2007, 51, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tähtinen, R.M.; Cartwright, R.; Vernooij, R.W.M.; Rortveit, G.; Hunskaar, S.; Guyatt, G.H.; Tikkinen, K.A.O. Long-term risks of stress and urgency urinary incontinence after different vaginal delivery modes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 220, 181.e1–181.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantilla Toloza, S.C.; Villareal Cogollo, A.F.; Peña García, K.M. Pelvic floor training to prevent stress urinary incontinence: A systematic review. Actas Urol. Esp. (Engl. Ed.) 2024, 48, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavender, T.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; Neilson, J.P.; Kingdon, C.; Gyte, G.M. Caesarean section for non-medical reasons at term. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 2012, CD004660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todhunter-Brown, A.; Hazelton, C.; Campbell, P.; Elders, A.; Hagen, S.; McClurg, D. Conservative interventions for treating urinary incontinence in women: An overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 9, CD012337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenes Bermúdez, F.J.; Cozar Olmo, J.M.; Esteban Fuertes, M.; Fernández-Pro Ledesma, A.; Molero García, J.M. Criterios de derivación en incontinencia urinaria para atención primaria [Urinary incontinence referral criteria for primary care]. Semergen 2013, 39, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No UI 1 (mean/sd) (%) N = 197 | UI (mean/sd) (%) N = 228 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at delivery | 31.86/5.25 | 33.34/4.85 | 0.027 |

| <30 | 28.43% | 21.05% | |

| 30–35 | 47.21% | 46.05% | 0.081 |

| >35 | 24.37% | 32.89% | |

| Age current | 40.51/5.43 | 41.68/5 | 0.0205 |

| <30 | 3.05% | 1.75% | |

| 30–35 | 15.74% | 8.77% | 0.053 |

| >35 | 81.22% | 89.47% | |

| Educational Level | |||

| High | 81.22% | 79.39% | |

| Low | 18.78% | 20.61% | 0.636 |

| Job occupation | |||

| No physical effort | 52.79% | 54.39% | |

| Physical effort | 46.70% | 45.61% | 0.539 |

| Current BMI 2 | 23.62/4.24 | 24.35/4.44 | 0.0863 |

| <18.5 | 4.06% | 3.95% | |

| 18.5–29.9 | 90.36% | 84.65% | 0.105 |

| >30 | 5.58% | 11.40% | |

| Family history | |||

| No | 83.25% | 70.48% | |

| Yes | 16.75% | 29.52% | 0.002 |

| Medical history | |||

| No | 73.60% | 63.60% | |

| Yes | 26.40% | 36.40% | 0.027 |

| Physical exercise | |||

| No | 26.40% | 29.82% | |

| Yes-High impact | 21.83% | 18.86% | 0.636 |

| Yes-Low impact | 51.78% | 51.32% | |

| Constipation | |||

| No | 83.16% | 83.33% | |

| Yes | 16.84% | 16.67% | 0.963 |

| No UI 1 (mean/sd) (%) N = 197 | UI (mean/sd) (%) N = 228 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-pregancy BMI 2 | 22.66/3.72 | 23.01/3.89 | 0.35 |

| <18.5 | 8.12% | 5.26% | |

| 18.5–29.9 | 86.80% | 89.04% | 0.485 |

| >30 | 5.08% | 5.70% | |

| BMI at delivery | 27.26/4.21 | 27.71/4.28 | 0.2828 |

| <18.5 | 0.51% | 0.00% | |

| 18.5–29.9 | 79.70% | 73.68% | 0.167 |

| >30 | 18.80% | 26.32% | |

| Weight gain (kg) | 12.12/5.64 | 12.47/6.33 | 0.548 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 39.21/1.83 | 38.98/2.10 | 0.2334 |

| Infant birthweight (g) | 3202/548 | 3163/585 | 0.4769 |

| <3000 | 31.98% | 32.89% | |

| 3000–3999 | 61.42% | 62.28% | 0.73 |

| >4000 | 6.60% | 4.82% | |

| Type of birth | |||

| Vaginal (instrumental + eutocic) | 73.10% | 81.14% | |

| Cesarean section | 26.90% | 18.86% | 0.048 |

| Episiotomy (N = 330) | |||

| No | 19.31% | 14.59% | |

| Yes | 80.69% | 85.41% | 0.254 |

| Risk/Confounding Factors | Crude OR (95% CI) | p | aOR (95% CI) 1 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at delivery | ||||

| 30–35 | 1.32 (0.81–2.12) | 0.257 | 0.86 (0.43–1.72) | 0.671 |

| >35 | 1.82 (1.07–3.09) | 0.026 | 1.20 (0.58–2.49) | 0.629 |

| Current age | ||||

| 30–35 | 0.97 (0.24–3.86) | 0.963 | 1.05 (0.25–4.34) | 0.944 |

| >35 | 1.91 (0.53–6.89) | 0.322 | 2.31 (0.55–9.71) | 0.254 |

| Current BMI 2 | ||||

| 18.5–29.9 | 0.96 (0.37–2.55) | 0.941 | 0.93 (0.34–2.55) | 0.882 |

| >30 | 2.10 (0.64–6.87) | 0.219 | 2.25 (0.66–7.68) | 0.195 |

| Type of birth | ||||

| Cesarean section | 0.63 (0.40–0.99) | 0.049 | 0.52 (0.32–0.85) | 0.009 |

| Family history | ||||

| Yes | 2.08 (1.30–3.33) | 0.002 | 2.03 (1.25–3.32) | 0.004 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Yes | 1.59 (1.05–2.42) | 0.028 | 1.58 (1.02–2.45) | 0.04 |

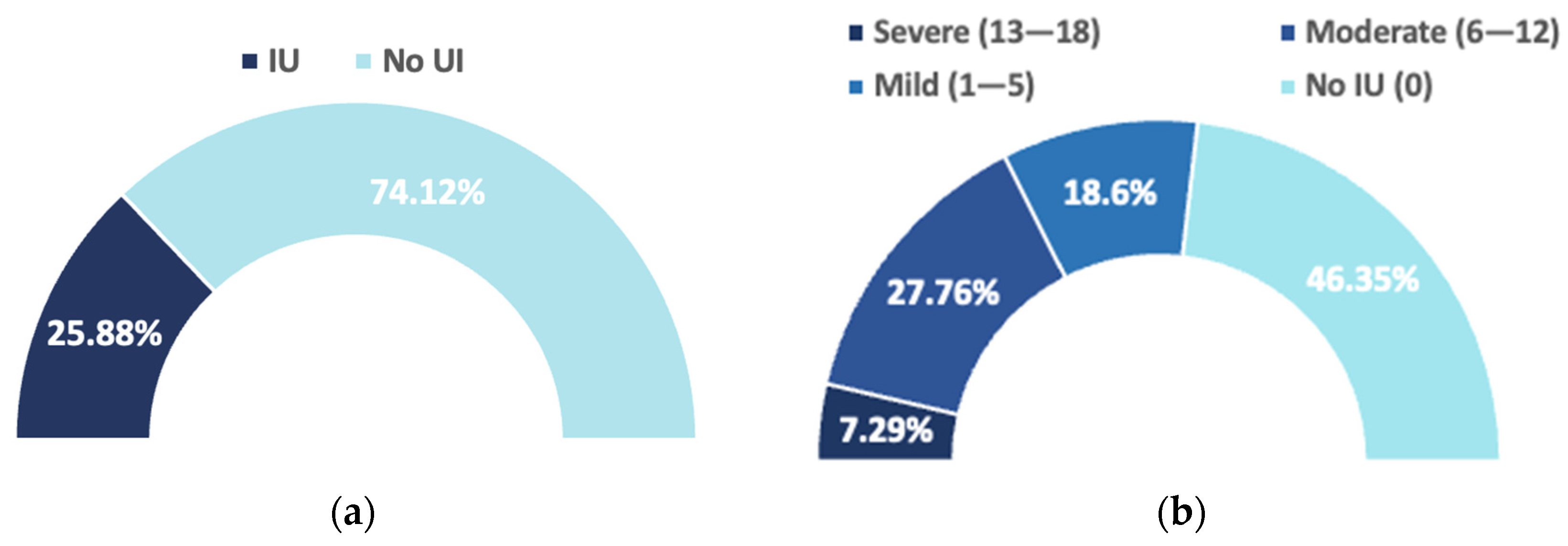

| ICIQ-IU-SF Final Score | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| No urinary incontinence (0) | 197 | 46.35 |

| Mild (1–5) | 79 | 18.6 |

| Moderate (6–12) | 118 | 27.76 |

| Severe (13–18) | 31 | 7.29 |

| Very severe (19–21) | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Serrano-Raya, L.; Esplugues, A.; Ferreros Villar, I.; Vallés-Murcia, N.; Muñoz Esteban, P.; Torres López, M.S.; Turrión Martínez, E.; Errandonea García, P.; Nohales Alfonso, F.J.; González-Timoneda, A. Prevalence and Impact of Urinary Incontinence at 5–10 Years After a Singleton Birth. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010252

Serrano-Raya L, Esplugues A, Ferreros Villar I, Vallés-Murcia N, Muñoz Esteban P, Torres López MS, Turrión Martínez E, Errandonea García P, Nohales Alfonso FJ, González-Timoneda A. Prevalence and Impact of Urinary Incontinence at 5–10 Years After a Singleton Birth. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010252

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerrano-Raya, Lola, Ana Esplugues, Inmaculada Ferreros Villar, Nerea Vallés-Murcia, Paula Muñoz Esteban, María Sol Torres López, Elisa Turrión Martínez, Patxi Errandonea García, Francisco Jose Nohales Alfonso, and Alba González-Timoneda. 2026. "Prevalence and Impact of Urinary Incontinence at 5–10 Years After a Singleton Birth" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010252

APA StyleSerrano-Raya, L., Esplugues, A., Ferreros Villar, I., Vallés-Murcia, N., Muñoz Esteban, P., Torres López, M. S., Turrión Martínez, E., Errandonea García, P., Nohales Alfonso, F. J., & González-Timoneda, A. (2026). Prevalence and Impact of Urinary Incontinence at 5–10 Years After a Singleton Birth. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010252