Effectiveness of Intranasal Esketamine on Suicidal Ideation and Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Longitudinal Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Recruitment and Assessment

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Antidepressant |

| AP | Antipsychotic |

| ASST | Azienda Socio-Sanitaria Territoriale |

| BD | Bipolar Disorder |

| BDZ | Benzodiazepine |

| C-SSRS | Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale |

| CGI-SS-r | Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Suicidality-revised |

| DSM-5-TR | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5ª ed., Text Revision |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration. |

| GCP | Good Clinical Practice |

| HAM-D | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| IRCCS | Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico |

| MADRS | Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

| MDE | Major Depressive Episode |

| MS | Mood Stabilizer |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| SA | Suicide Attempt |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SNRI | Serotonin–Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor |

| SSRI | Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor |

| SI | Suicidal Ideation |

| TRD | Treatment-Resistant Depression |

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide Worldwide in 2019 Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.-L.; Qian, Y.; Jin, X.-H.; Yu, H.-R.; Wu, H.; Du, L.; Chen, H.-L.; Shi, Y.-Q. Suicide rates among people with serious mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2021, 53, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- la Torre, J.A.-D.; Vilagut, G.; Ronaldson, A.; Serrano-Blanco, A.; Martín, V.; Peters, M.; Valderas, J.M.; Dregan, A.; Alonso, J. Prevalence and variability of current depressive disorder in 27 European countries: A population-based study. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e729–e738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voelker, J.; Kuvadia, H.; Cai, Q.; Wang, K.; Daly, E.; Pesa, J.; Connolly, N.; Sheehan, J.J.; Wilkinson, S.T. United States national trends in prevalence of major depressive episode and co-occurring suicidal ideation and treatment resistance among adults. J. Affect Disord. Rep. 2021, 5, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holma, K.M.; Melartin, T.K.; Haukka, J.; Holma, I.A.K.; Sokero, T.P.; Isometsä, E.T. Incidence and Predictors of Suicide Attempts in DSM–IV Major Depressive Disorder: A Five-Year Prospective Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokero, T.P.; Melartin, T.K.; Rytsälä, H.J.; Leskelä, U.S.; Lestelä-Mielonen, P.S.; Isometsä, E.T. Suicidal Ideation and Attempts Among Psychiatric Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003, 64, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ballegooijen, W.; Eikelenboom, M.; Fokkema, M.; Riper, H.; van Hemert, A.M.; Kerkhof, A.J.; Penninx, B.W.; Smit, J.H. Comparing factor structures of depressed patients with and without suicidal ideation, a measurement invariance analysis. J. Affect Disord. 2019, 245, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dold, M.; Bartova, L.; Fugger, G.; Kautzky, A.; Souery, D.; Mendlewicz, J.; Papadimitriou, G.N.; Dikeos, D.; Ferentinos, P.; Porcelli, S.; et al. Major Depression and the Degree of Suicidality: Results of the European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression (GSRD). Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018, 21, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Castroman, J.; Jaussent, I.; Gorwood, P.; Courtet, P. Suicidal Depressed Patients Respond Less Well to Antidepressants in the Short Term. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, D.; Rihmer, Z.; Rujescu, D.; Sarchiapone, M.; Sokolowski, M.; Titelman, D.; Zalsman, G.; Zemishlany, Z.; Carli, V. The European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on suicide treatment and prevention. Eur. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.N.; Michail, M.; Thompson, A.; Fiedorowicz, J.G. Psychiatric Emergencies. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 101, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Bassett, D.; Boyce, P.; Bryant, R.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Fritz, K.; Hopwood, M.; Lyndon, B.; Mulder, R.; Murray, G.; et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 1087–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floriano, I.; Silvinato, A.; Bernardo, W.M. The use of esketamine in the treatment of patients with severe depression and suicidal ideation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2023, 69, e2023D694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinotti, G.; Vita, A.; Fagiolini, A.; Maina, G.; Bertolino, A.; Dell’Osso, B.; Siracusano, A.; Clerici, M.; Bellomo, A.; Sani, G.; et al. Real-world experience of esketamine use to manage treatment-resistant depression: A multicentric study on safety and effectiveness (REAL-ESK study). J. Affect Disord. 2022, 319, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, D.-J.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, L.; Borentain, S.; Guo, S.; Mathews, M.; Anjo, J.; Nash, A.I.; O’hara, M.; Canuso, C.M. Esketamine versus placebo on time to remission in major depressive disorder with acute suicidality. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, D.F.; Fu, D.-J.; Qiu, X.; Lane, R.; Lim, P.; Kasper, S.; Hough, D.; Drevets, W.C.; Manji, H.; Canuso, C.M. Esketamine Nasal Spray for Rapid Reduction of Depressive Symptoms in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder Who Have Active Suicide Ideation With Intent: Results of a Phase 3, Double-Blind, Randomized Study (ASPIRE II). Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 24, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Chen-Li, D.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Carvalho, I.; Lui, L.M.; Gill, H.; Narsi, F.; Mansur, R.B.; et al. The acute antisuicidal effects of single-dose intravenous ketamine and intranasal esketamine in individuals with major depression and bipolar disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 134, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Sanacora, G.; Murrough, J.W.; Berk, M.; Brietzke, E.; Dodd, S.; Gorwood, P.; Ho, R.; et al. Synthesizing the Evidence for Ketamine and Esketamine in Treatment-Resistant Depression: An International Expert Opinion on the Available Evidence and Implementation. Am. J. Psychiatry 2021, 178, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, K.; Brown, G.K.; Stanley, B.; Brent, D.A.; Yershova, K.V.; Oquendo, M.A.; Currier, G.W.; Melvin, G.A.; Greenhill, L.; Shen, S.; et al. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial Validity and Internal Consistency Findings From Three Multisite Studies With Adolescents and Adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindh, Å.U.; Waern, M.; Beckman, K.; Renberg, E.S.; Dahlin, M.; Runeson, B. Short term risk of non-fatal and fatal suicidal behaviours: The predictive validity of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale in a Swedish adult psychiatric population with a recent episode of self-harm. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greist, J.H.; Mundt, J.C.; Gwaltney, C.J.; Jefferson, J.W.; Posner, K. Predictive Value of Baseline Electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (eC-SSRS) Assessments for Identifying Risk of Prospective Reports of Suicidal Behavior During Research Participation. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 11, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, S.A.; Åsberg, M. A New Depression Scale Designed to be Sensitive to Change. Br. J. Psychiatry 1979, 134, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, N.; Yamada, A.; Shiraishi, A.; Shimizu, H.; Goto, R.; Tominaga, Y. Efficacy and safety of fixed doses of intranasal Esketamine as an add-on therapy to Oral antidepressants in Japanese patients with treatment-resistant depression: A phase 2b randomized clinical study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.J.; Ju, P.-C.; Sulaiman, A.H.; Aziz, S.A.; Paik, J.-W.; Tan, W.; Bai, D.; Li, C.-T. Long-term Safety and Efficacy of Esketamine Nasal Spray Plus an Oral Antidepressant in Patients with Treatment-resistant Depression– an Asian Sub-group Analysis from the SUSTAIN-2 Study. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2022, 20, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, N.; Chen, L.; Lane, R.; Doherty, T.; Drevets, W.C.; Morrison, R.L.; Sanacora, G.; Wilkinson, S.T.; Popova, V.; Fu, D.-J. Long-term safety and maintenance of response with esketamine nasal spray in participants with treatment-resistant depression: Interim results of the SUSTAIN-3 study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 48, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawczak, P.; Feszak, I.; Bączek, T. Ketamine, Esketamine, and Arketamine: Their Mechanisms of Action and Applications in the Treatment of Depression and Alleviation of Depressive Symptoms. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, J.C.; DeRubeis, R.J.; Hollon, S.D.; Dimidjian, S.; Amsterdam, J.D.; Shelton, R.C.; Fawcett, J. Antidepressant Drug Effects and Depression Severity. JAMA 2010, 303, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raciti, L.; Formica, C.; Raciti, G.; Quartarone, A.; Calabrò, R.S. Gender and Neurosteroids: Implications for Brain Function, Neuroplasticity and Rehabilitation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moderie, C.; Nuñez, N.; Fielding, A.; Comai, S.; Gobbi, G. Sex Differences in Responses to Antidepressant Augmentations in Treatment-Resistant Depression. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 25, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmia, I.M.; Just, K.S.; Yamoune, S.; Müller, J.P.; Stingl, J.C. Pharmacogenetic and Drug Interaction Aspects on Ketamine Safety in Its Use as Antidepressant—Implications for Precision Dosing in a Global Perspective. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 88, 5149–5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitah, K.; Siegel, A.N.; Lipsitz, O.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Meshkat, S.; Lee, Y.; Mansur, R.B.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.; McIntyre, R.S.; et al. Sex Differences in Ketamine’s Therapeutic Effects for Mood Disorders: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 312, 114579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiadis, V.; Raffone, F.; Atripaldi, D.; Testa, S.; Giunnelli, P.; Cerlino, R.; Russo, M.; Martini, A.; Pessina, E.; Cattaneo, C.I.; et al. Gender Differences in Suicidal and Self-Harming Responses to Esketamine: A Real-World Retrospective Study. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2025, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üzümçeker, E. Traditional Masculinity and Men’s Psychological Help-Seeking: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Psychol. 2025, 60, 70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bye, H.H.; Måseidvåg, F.L.; Harris, S.M. Men’s Help-Seeking Willingness and Disclosure of Depression: Experimental Evidence for the Role of Pluralistic Ignorance. Sex Roles 2025, 91, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtet, P.; Jaussent, I.; Lopez-Castroman, J.; Gorwood, P. Poor response to antidepressants predicts new suicidal ideas and behavior in depressed outpatients. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014, 24, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Mean age (±SD) | 49.1 ± 16.8 years |

| Gender | 55% female 45% male |

| Relationship status | 58.8% partnered 41.2% single |

| Employment status | 46.2% unemployed 53.8% employed |

| Diagnosis | 84% MDE in MDD 16% MDE in BD |

| Age at first MDE (mean ± SD) | 31.5 ± 15.5 years |

| Lifetime number of MDE | 4.8 ± 5.9 |

| Current MDE duration (mean in days ± SD) | 241 ± 194 days |

| Lifetime number of SAs (mean ± SD) | 0.4 ± 0.8 |

| Family history for depression or SAs (%) | Yes 70% No 30% |

| Psychopharmacotherapy at baseline | |

| SSRIs | 60% |

| SNRIs | 40% |

| Other ADs | 43.8% |

| Atypical APs | 52.5% |

| MSs | 38.8% |

| BDZs | 56.2% |

| N CSSRS | C-SSRS ± SD | p | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | 80 | 1.56 ± 1.65 | — | |

| T1 | 79 | 0.78 ± 1.28 | <0.001 | 0.99 |

| T2 | 65 | 0.63 ± 1.34 | <0.001 | 1.58 |

| T3 | 62 | 0.63 ± 1.26 | <0.001 | 2.11 |

| T4 | 55 | 0.44 ± 1.05 | <0.001 | 2.03 |

| T5 | 40 | 0.12 ± 0.52 | <0.001 | 1.82 |

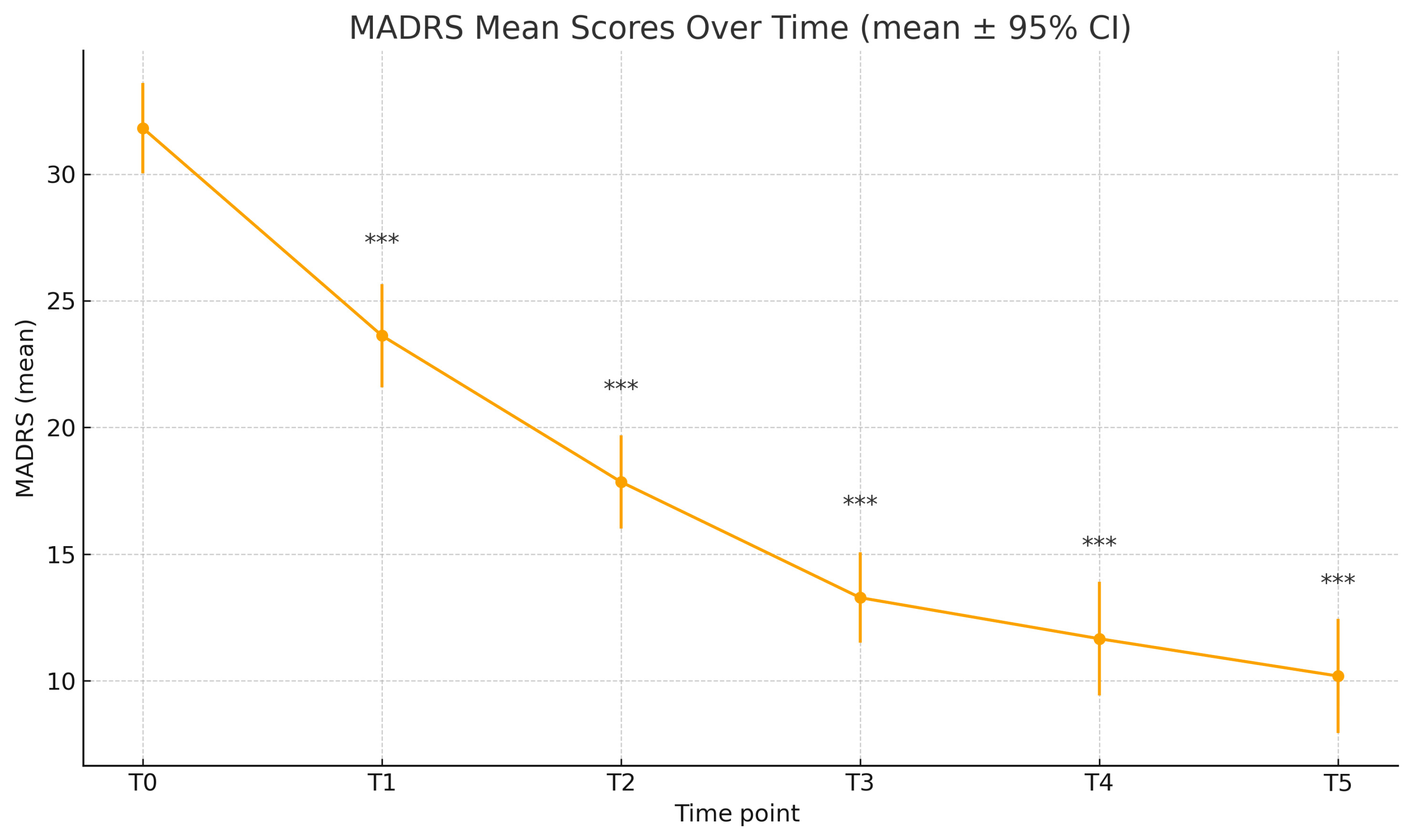

| N MADRS | MADRS ± SD | p | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | 31.81 ± 7.94 | — | ||

| T1 | 78 | 23.62 ± 9.08 | <0.001 | 0.59 |

| T2 | 72 | 17.85 ± 7.83 | <0.001 | 0.67 |

| T3 | 63 | 13.28 ± 7.13 | <0.001 | 0.58 |

| T4 | 56 | 11.66 ± 8.37 | <0.001 | 0.76 |

| T5 | 43 | 10.19 ± 7.33 | <0.001 | 1.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leonardi, M.; Frediani, A.; Angeletti, M.C.; Biseo, M.; Versaci, G.; Castiglioni, M.; Olivola, M.; Vismara, M.; Varinelli, A.; Bosi, M.; et al. Effectiveness of Intranasal Esketamine on Suicidal Ideation and Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010250

Leonardi M, Frediani A, Angeletti MC, Biseo M, Versaci G, Castiglioni M, Olivola M, Vismara M, Varinelli A, Bosi M, et al. Effectiveness of Intranasal Esketamine on Suicidal Ideation and Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):250. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010250

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeonardi, Matteo, Alice Frediani, Maria Chiara Angeletti, Monica Biseo, Giada Versaci, Michele Castiglioni, Miriam Olivola, Matteo Vismara, Alberto Varinelli, Monica Bosi, and et al. 2026. "Effectiveness of Intranasal Esketamine on Suicidal Ideation and Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Longitudinal Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010250

APA StyleLeonardi, M., Frediani, A., Angeletti, M. C., Biseo, M., Versaci, G., Castiglioni, M., Olivola, M., Vismara, M., Varinelli, A., Bosi, M., Benatti, B., Brondino, N., & Dell’osso, B. M. (2026). Effectiveness of Intranasal Esketamine on Suicidal Ideation and Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010250