Comparative Outcomes of Living and Deceased Donor Liver Transplantation in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

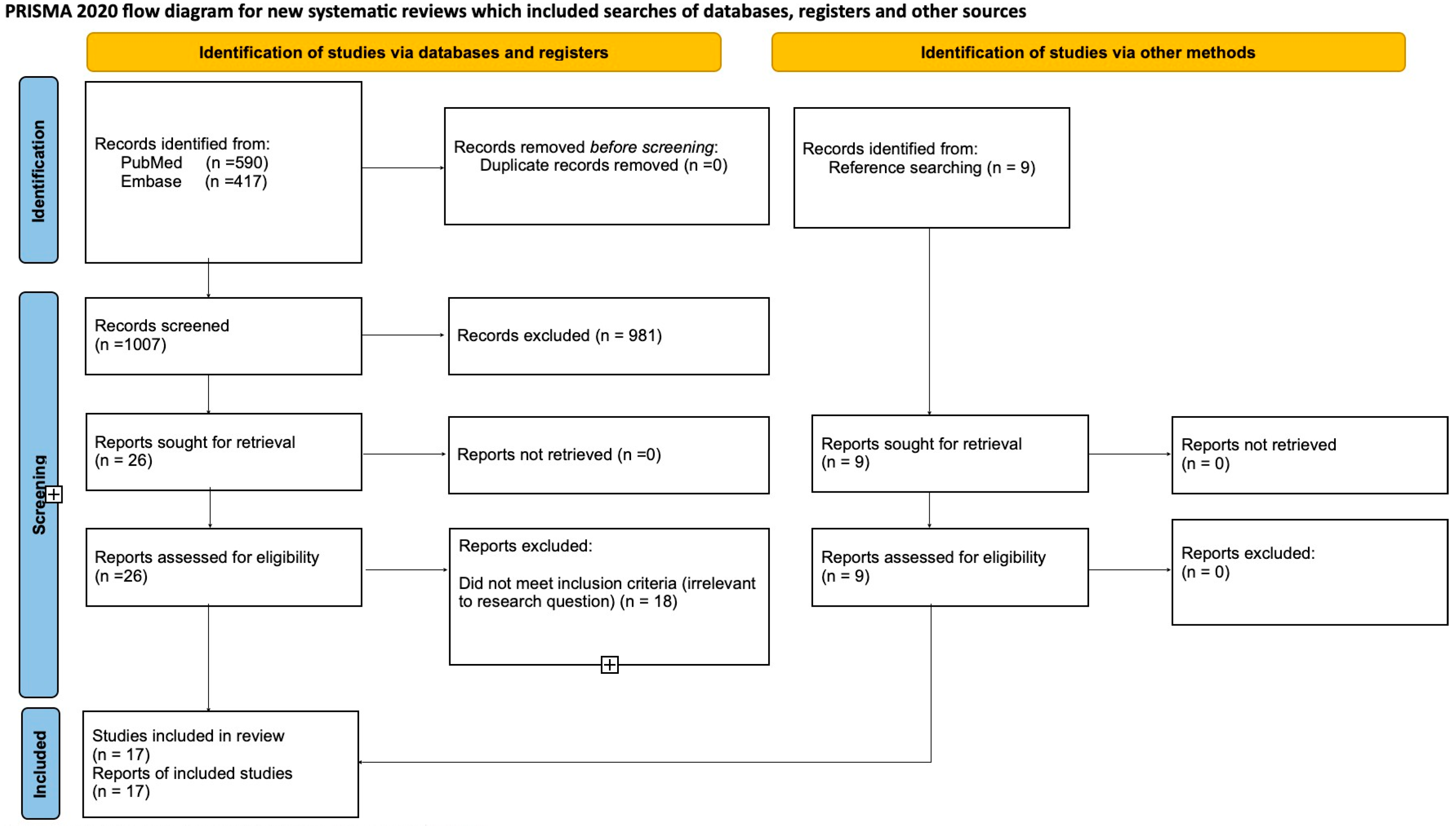

3.1. Study Selection

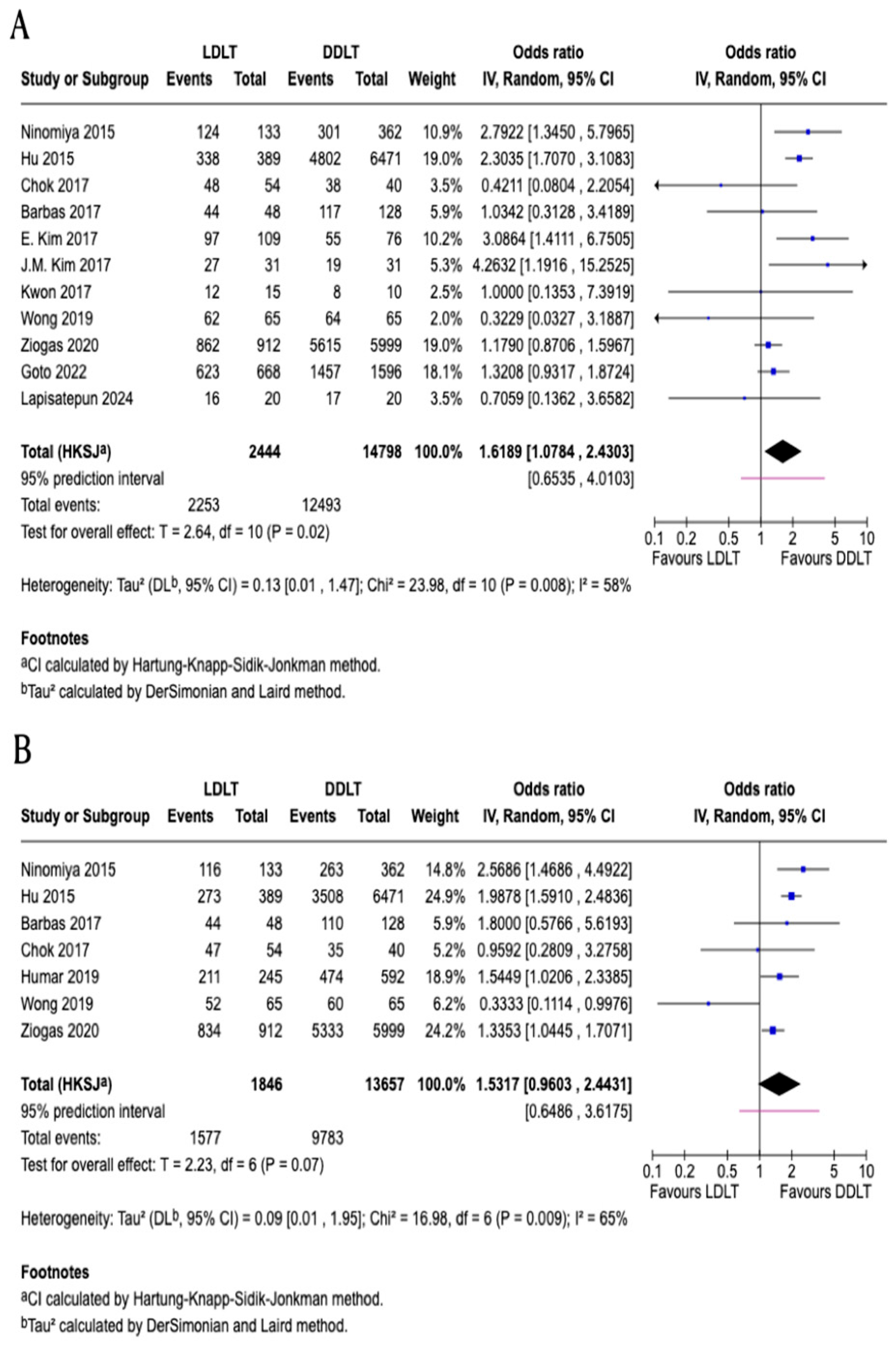

3.2. One-Year Patient Survival

3.3. Three-Year Patient Survival

3.4. Five-Year Patient Survival

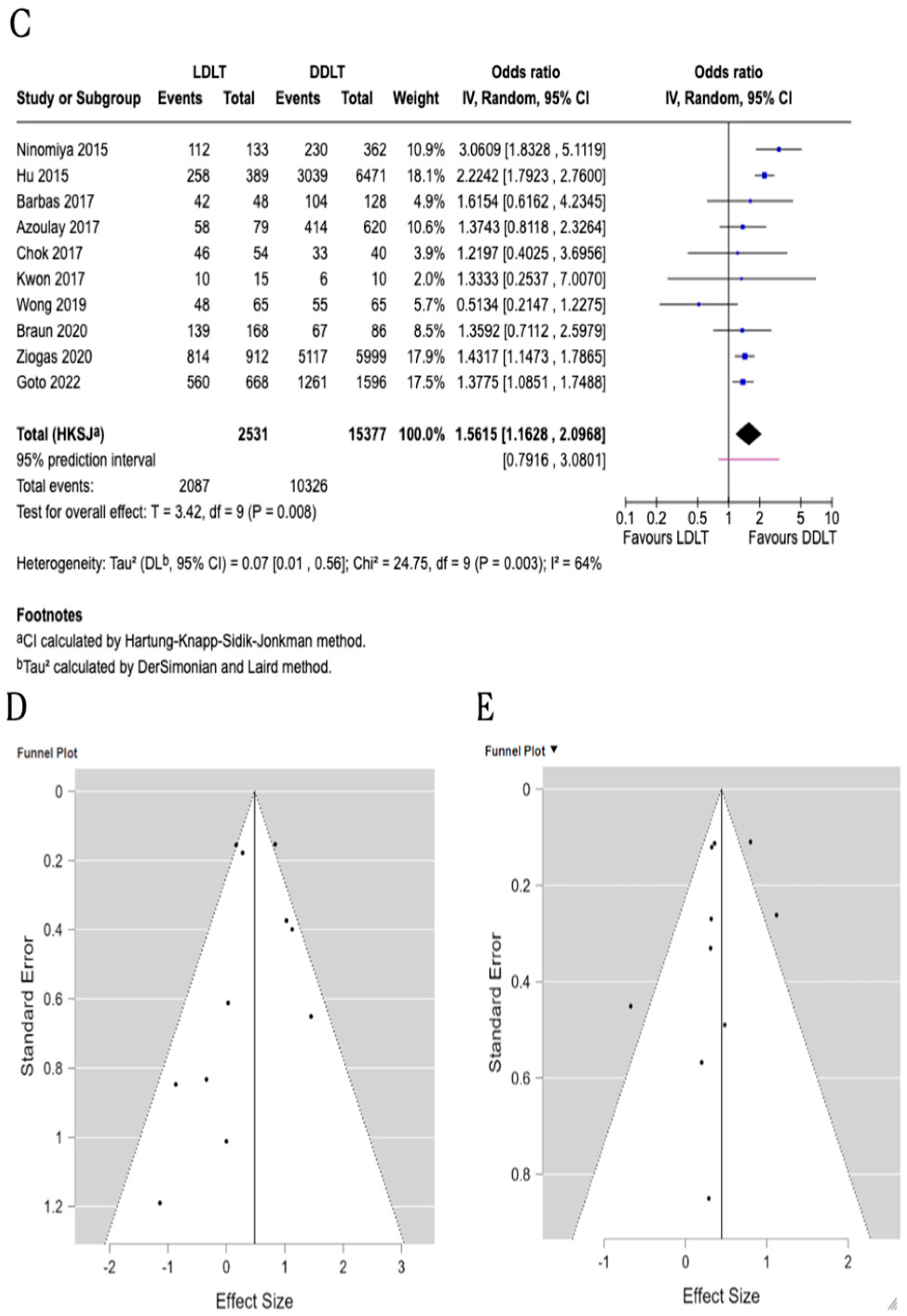

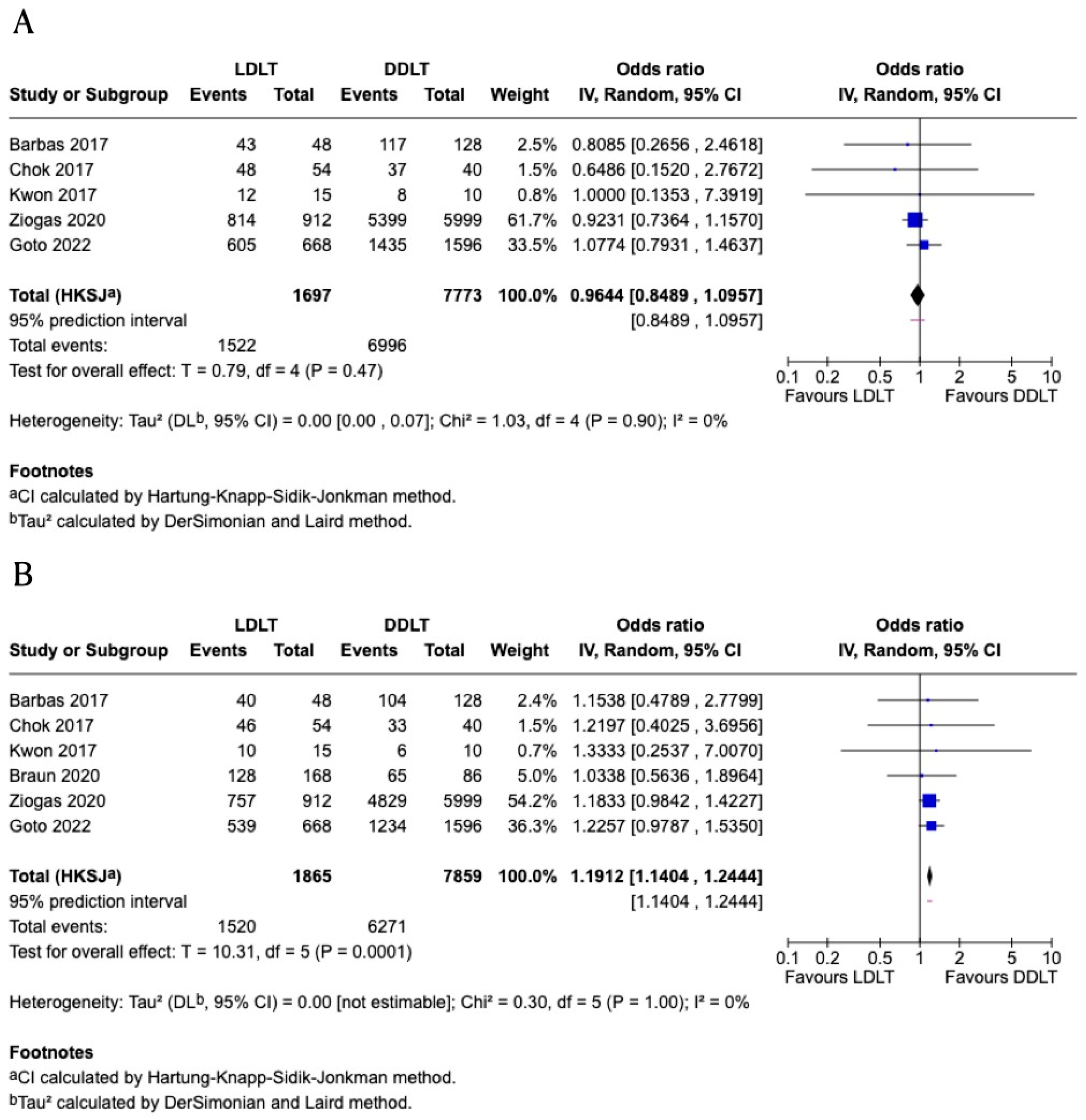

3.5. One-Year Graft Survival

3.6. Five-Year Graft Survival

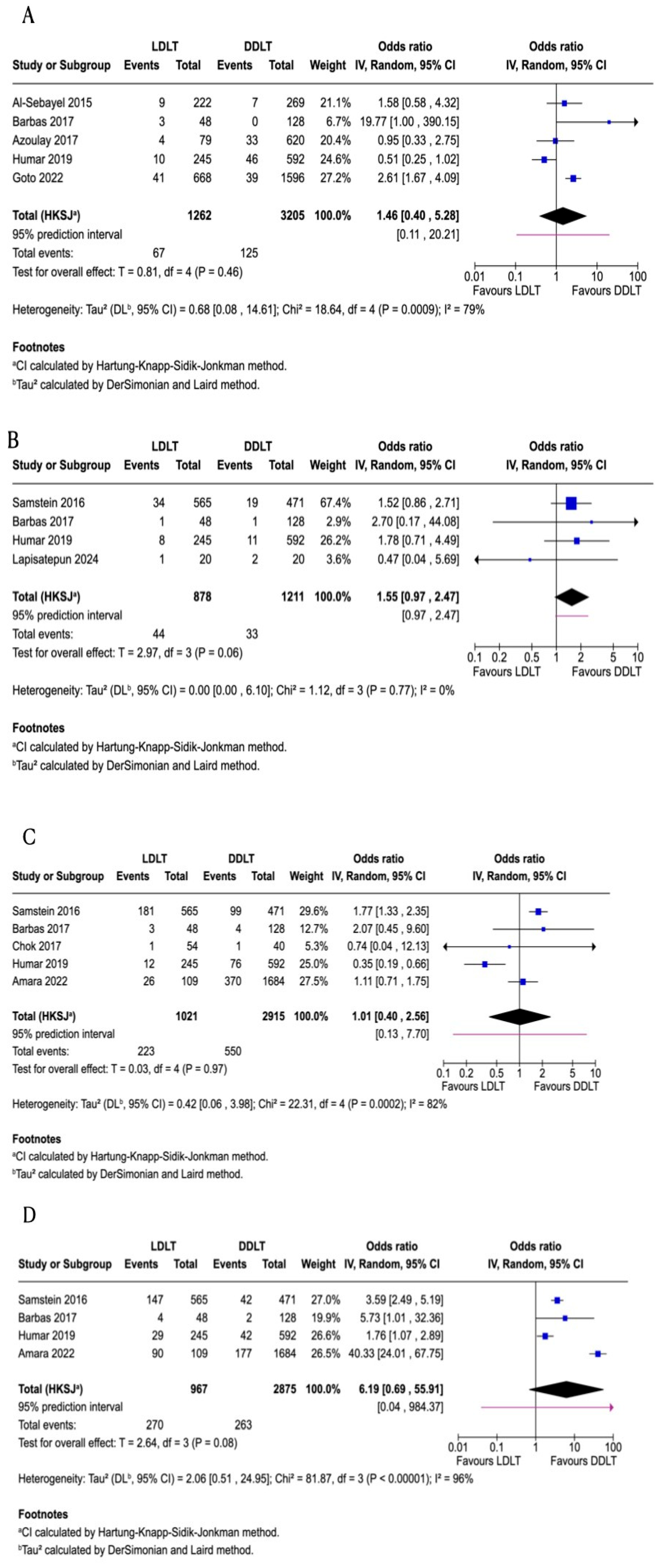

3.7. Re-Transplantation

3.8. Hepatic Artery Thrombosis

3.9. Biliary Stricture

3.10. Biliary Leakage

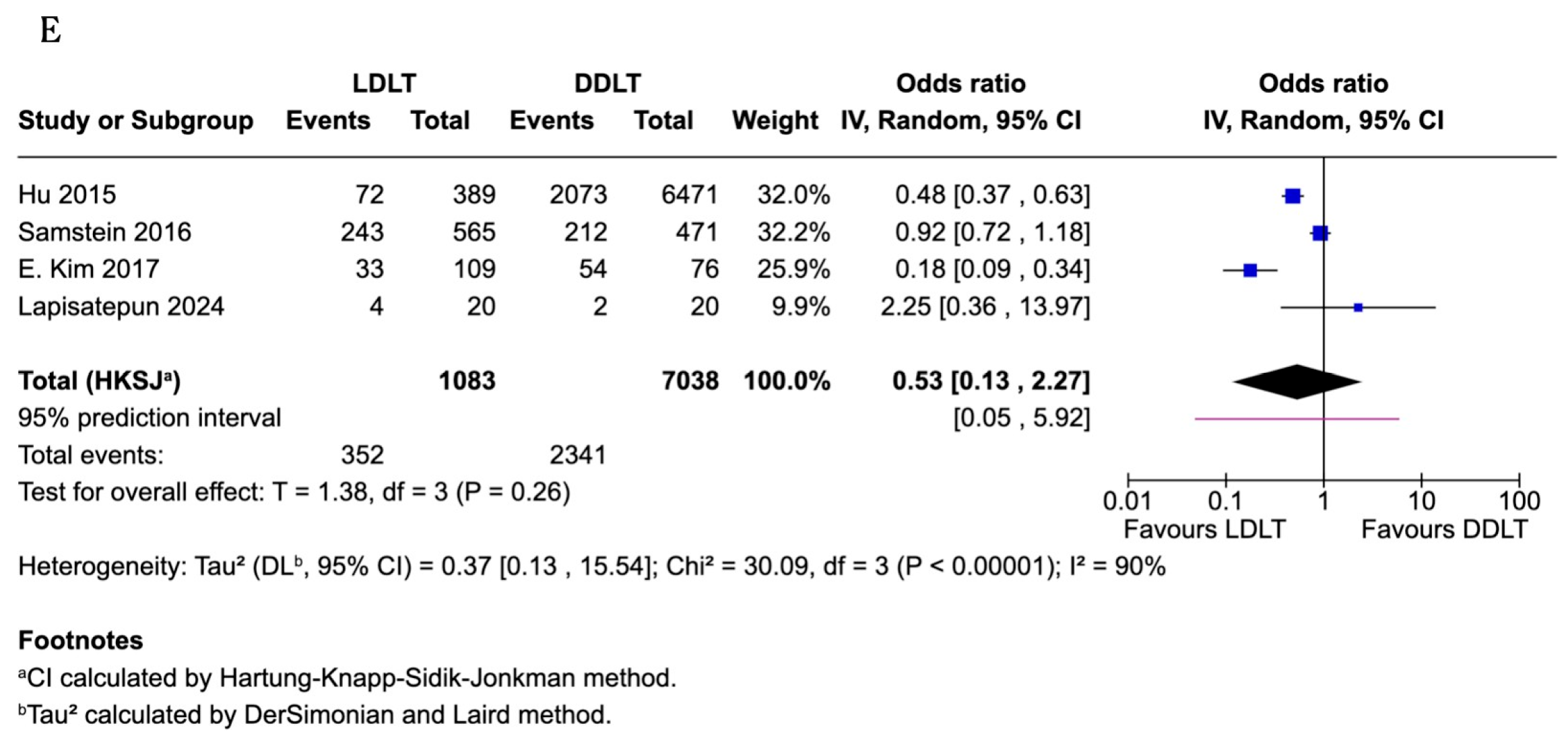

3.11. Infections

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LDLT | Living Donor Liver Transplantation |

| DDLT | Deceased Donor Liver Transplantation |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| ALD | Alcoholic liver disease |

| CLD | Cholestatic liver disease |

Appendix A. Search Strategy

| Database: PubMed Keywords and MeSH Terms: General Keywords: 1-Liver transplantation: liver transplantation OR living donor liver transplantations OR deceased donor liver transplantation OR liver transplantation techniques OR LDLT Surgical innovations OR LDLT trends OR DDLT trends 2-Clinical Outcomes: post operation outcomes OR transplant outcome OR therapeutic outcome OR Clinical Outcomes OR Living donor liver transplantation outcomes LDLT OR deceased donor liver transplantation outcomes OR LDLT Graft survival OR DDLT Graft survival OR LDLT Complications. MeSH Terms: 1-Liver Transplantation: (“Liver Transplantation/adverse effects”[Mesh] OR “Liver Transplantation/instrumentation”[Mesh] OR “Liver Transplantation/methods”[Mesh] OR “Liver Transplantation/mortality”[Mesh] OR “Liver Transplantation/statistics and numerical data”[Mesh]) 2-Living donor: (“Living Donors/statistics and numerical data”[Mesh] OR “Living Donors/supply and distribution”[Mesh]) 3-Tissue Donors: (“Tissue Donors/statistics and numerical data”[Mesh] OR “Tissue Donors/supply and distribution”[Mesh]) 4-ClinicalOutcomes:(“PostoperativeComplications/etiology”[Mesh]OR “Postoperative Complications/mortality”[Mesh] OR “Postoperative Complications/surgery”[Mesh]) 5-Graft Rejection: (“Graft Rejection/complications”[Mesh] OR “Graft Rejection/epi-demiology”[ Mesh] OR “Graft Rejection/mortality”[Mesh] OR “Graft Rejection/phys-iopathology”[ Mesh] OR “Graft Rejection/prevention and control”[Mesh] OR “Graft Rejection/surgery”[Mesh]) 6-Postoperative Complications: (“Postoperative Complications/epidemiology”[Mesh] OR “Postoperative Complications/mortality”[Mesh] OR “Postoperative Complications/physiopathology”[Mesh] OR “Postoperative Complications/prevention and control”[Mesh] OR “Postoperative Complications/surgery”[Mesh]) 7-Survival Analysis: (“Survival Analysis”[Mesh]) 8-TreatmentOutcome:(“Treatment Outcome”[Mesh]) 9-Graft survival:(“Graft Survival”[Mesh]) Search Strategies: PubMed 1-(“Liver Transplantation/adverse effects”[Mesh] OR “Liver Transplan-tation/instrumentation”[Mesh] OR “Liver Transplantation/methods”[Mesh] OR “Liver Transplantation/mortality”[Mesh] OR “Liv-er Transplantation/statistics and numerical data”[Mesh])OR (“Living Donors/statistics and numerical data”[Mesh] OR “Living Donors/supply and distribution”[Mesh]) OR (“Tissue Donors/statistics and numerical data”[Mesh] OR “Tissue Donors/supply and distribution”[Mesh]) OR liver transplantation techniques OR LDLT Surgical innovations OR LDLT trends OR DDLT trends 2-ClinicalOutcomes:(“Postoperative Complications/mortality”[Mesh] OR “Postoperative Complications/surgery”[Mesh]) OR post operation outcomes OR transplant outcome OR therapeutic outcome OR Clinical Outcomes OR Living donor liver transplantation outcomes LDLT OR deceased donor liver transplantation outcomes OR LDLT Graft survival OR DDLT Graft survival OR LDLT Complications. 3-(“Graft Rejection/complications”[Mesh] OR “Graft Rejection/epi-demiology”[ Mesh] OR “Graft Rejection/mortality”[Mesh] OR “Graft Rejection/physiopathology”[Mesh] OR “Graft Rejection/prevention and control”[Mesh] OR “Graft Rejection/surgery”[Mesh])OR “Postopera-tive Complications/epidemiology”[Mesh] OR “Postoperative Complica-tions/mortality”[Mesh] OR “Postoperative Complications/physiopathol-ogy”[ Mesh] OR “Postoperative Complications/prevention and control”[Mesh] OR “Postoperative Complications/surgery”[Mesh] OR: (“Survival Analysis”[Mesh]) OR (“Treatment Outcome”[Mesh]) OR (“Graft Survival”[Mesh]) OR liver transplantation OR living donor liver transplantations OR deceased donor liver transplantation Database: Embase Keywords and Emtree Terms: General Keywords: 1-Liver transplantation: liver transplantation OR living donor liver transplantations OR deceased donor liver transplantation OR liver transplantation techniques OR LDLT Surgical innovations OR LDLT trends OR DDLT trends 2-Clinical Outcomes: post operation outcomes OR transplant outcome OR therapeutic outcome OR Clinical Outcomes OR Living donor liver transplantation outcomes LDLT OR deceased donor liver transplantation outcomes OR LDLT Graft survival OR DDLT Graft survival OR LDLT Complications. Emtree Terms: • ’adult patient’/exp • ’liver transplantation’/exp • ’living donor liver transplantation’/exp • ’deceased donor liver transplantation’/exp • ’postoperative complication’/exp • ’transplant complication’/exp • ’adult patient’/exp • ’small for size syndrome’/exp Search Strategies: embase 1-(‘adult patient’/exp OR adult:ti,ab OR ‘adult population’:ti,ab)AND(‘liver transplanta-tion’/exp OR ‘liver transplant*’:ti,ab OR ‘hepatic transplant*’:ti,ab)AND((‘living donor liver transplantation’/exp OR ‘LDLT’:ti,ab OR ‘living donor liver transplant*’:ti,ab)AND(‘deceased donor liver transplantation’/exp OR ‘DDLT’:ti,ab OR ‘deceased donor liver transplant*’:ti,ab)) 2-(‘adult patient’/exp OR adult:ti,ab OR ‘adult population’:ti,ab)AND(‘liver transplanta-tion’/exp OR ‘liver transplant*’:ti,ab)AND((‘living donor liver transplantation’/exp OR ‘LDLT’:ti,ab)AND(‘deceased donor liver transplantation’/exp OR ‘DDLT’:ti,ab))AND(‘small for size syndrome’/exp OR ‘small-for-size syndrome’:ti,ab OR ‘SFSS’:ti,ab OR ‘small graft*’:ti,ab OR ‘graft-to-recipient weight ratio’:ti,ab OR GRWR:ti,ab) 3-(‘adult patient’/exp OR adult:ti,ab OR ‘adult population’:ti,ab)AND(‘liver transplanta-tion’/exp OR ‘liver transplant*’:ti,ab)AND((‘living donor liver transplantation’/exp OR’LDLT’:ti,ab)AND(‘deceased donor liver transplantation’/exp OR ‘DDLT’:ti,ab))AND(‘postoperative complication’/exp OR ‘transplant complication’/exp OR complication*:ti,ab OR ‘biliary complication*’:ti,ab OR ‘vascular complication*’:ti,ab OR ‘graft failure’:ti,ab OR ‘rejection’:ti,ab) |

References

- Meirelles Junior, R.F.; Salvalaggio, P.; Rezende, M.B.; Evangelista, A.S.; Guardia, B.D.; Matielo, C.E.; Neves, D.B.; Pandullo, F.L.; Felga, G.E.; Alves, J.A.; et al. Liver transplantation: History, out-comes and perspectives. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2015, 13, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Qian, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, S. Clinical outcomes and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma treated by liver transplantation: A multi-centre comparison of living donor and deceased donor transplantation. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2016, 40, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, W.S.; Stephen, V.L.; Tat, H.O.; Hidetoshi, M.; Yuichi, K.; Glenda, A.B. Successful liver transplantation from a living donor to her son. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 322, 1505–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbetta, A.; Aljehani, M.; Kim, M.; Tien, C.; Ahearn, A.; Schilperoort, H.; Sher, L.; Emamaullee, J. Meta-analysis and meta-regression of outcomes for adult living donor liver transplantation versus deceased donor liver transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 2399–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenmeier, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Ganoza, A.; Crane, A.; Powers, C.; Gunabushanam, V.; Behari, J.; Molinari, M. Survival after live donor versus deceased donor liver transplantation: Propensity score-matched study. BJS Open 2024, 8, zrae058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Zeng, Y. Living or deceased organ donors in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB 2019, 21, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, A.B.; da Silva, C.M.; Nogueira, P.; Machado, M.V. Meta-Analysis: Comparison of Living Versus Deceased Liver Transplantation for Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 62, 768–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninomiya, M.; Shirabe, K.; Facciuto, M.E.; Schwartz, M.E.; Florman, S.S.; Yoshizumi, T.; Harimo-to, N.; Ikegami, T.; Uchiyama, H.; Maehara, Y. Comparative study of living and deceased donor liver transplantation as a treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2015, 220, 297–304.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sebayel, M.; Abaalkhail, F.; Hashim, A.; Al Bahili, H.; Alabbad, S.; Shoukdy, M.; Elsiesy, H. Living donor liver transplant versus cadaveric liver transplant survival in relation to model for end-stage liver disease score. Transplant. Proc. 2015, 47, 1211–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samstein, B.; Smith, A.R.; Freise, C.E.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Baker, T.; Olthoff, K.M.; Fisher, R.A.; Merion, R.M. Complications and Their Resolution in Recipients of Deceased and Living Donor Liv-er Transplants: Findings From the A2ALL Cohort Study. Am. J. Transplant. 2016, 16, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbas, A.S.; Goldaracena, N.; Dib, M.J.; Al-Adra, D.P.; Aravinthan, A.D.; Lilly, L.B.; Renner, E.L.; Selzner, N.; Bhat, M.; Cattral, M.S.; et al. Early Intervention with Live Donor Liver Transplantation Reduces Resource Utilization in NASH: The Toronto Experience. Transplant. Direct 2017, 3, e158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chok, K.S.; Fung, J.Y.; Chan, A.C.; Dai, W.C.; Sharr, W.W.; Cheung, T.T.; Chan, S.C.; Lo, C.M. Comparable Short- and Long-term Outcomes in Living Donor and Deceased Donor Liver Transplan-tations for Patients with Model for End-stage Liver Disease Scores >/=35 in a Hepatitis-B Endemic Area. Ann. Surg. 2017, 265, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoulay, D.; Audureau, E.; Bhangui, P.; Belghiti, J.; Boillot, O.; Andreani, P.; Castaing, D.; Cherqui, D.; Irtan, S.; Calmus, Y.; et al. Living or Brain-dead Donor Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Multicenter, Western, Intent-to-treat Cohort Study. Ann. Surg. 2017, 266, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Lim, S.; Chu, C.W.; Ryu, J.H.; Yang, K.; Park, Y.M.; Choi, B.H.; Lee, T.B.; Lee, S.J. Clinical Impacts of Donor Types of Living vs. Deceased Donors: Predictors of One-Year Mortality in Pa-tients with Liver Transplantation. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Lee, K.W.; Song, G.W.; Jung, B.H.; Lee, H.W.; Yi, N.J.; Kwon, C.H.D.; Hwang, S.; Suh, K.S.; Joh, J.W.; et al. Increased survival in hepatitis c patients who underwent living donor liver transplant: A case-control study with propensity score matching. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2017, 93, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.H.; Yoon, Y.I.; Song, G.W.; Kim, K.H.; Moon, D.B.; Jung, D.H.; Park, G.C.; Tak, E.Y.; Kirchner, V.A.; Lee, S.G. Living Donor Liver Transplantation for Patients Older Than Age 70 Years: A Single-Center Experience. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 2890–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, T.C.L.; Ng, K.K.C.; Fung, J.Y.Y.; Chan, A.A.C.; Cheung, T.T.; Chok, K.S.H.; Dai, J.W.C.; Lo, C.M. Long-Term Survival Outcome Between Living Donor and Deceased Donor Liver Transplant for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Intention-to-Treat and Propensity Score Matching Analyses. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 26, 1454–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humar, A.; Ganesh, S.; Jorgensen, D.; Tevar, A.; Ganoza, A.; Molinari, M.; Hughes, C. Adult Living Donor Versus Deceased Donor Liver Transplant (LDLT Versus DDLT) at a Single Center: Time to Change Our Paradigm for Liver Transplant. Ann. Surg. 2019, 270, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, H.J.; Dodge, J.L.; Grab, J.D.; Syed, S.M.; Roll, G.R.; Freise, C.E.; Roberts, J.P.; Ascher, N.L. Living Donor Liver Transplant for Alcoholic Liver Disease: Data from the Adult-to-adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Study. Transplantation 2020, 104, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziogas, I.A.; Alexopoulos, S.P.; Matsuoka, L.K.; Geevarghese, S.K.; Gorden, L.D.; Karp, S.J.; Perkins, J.D.; Montenovo, M.I. Living vs deceased donor liver transplantation in cholestatic liver disease: An analysis of the OPTN database. Clin. Transplant. 2020, 34, e14031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, T.; Ivanics, T.; Cattral, M.S.; Reichman, T.; Ghanekar, A.; Sapisochin, G.; McGilvray, I.D.; Sayed, B.; Lilly, L.; Bhat, M.; et al. Superior Long-Term Outcomes of Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation: A Cumulative Single-Center Cohort Study with 20 Years of Follow-Up. Liver Transplant. 2022, 28, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, D.; Parekh, J.; Sudan, D.; Elias, N.; Foley, D.P.; Conzen, K.; Grieco, A.; Braun, H.J.; Green-stein, S.; Byrd, C.; et al. Surgical complications after living and deceased donor liver transplant: The NSQIP transplant experience. Clin. Transplant. 2022, 36, e14610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapisatepun, W.; Junrungsee, S.; Chotirosniramit, A.; Udomsin, K.; Ko-Iam, W.; Lapisatepun, W.; Siripongpon, K.; Kiratipaisarl, W.; Bhanichvit, P.; Julphakee, T. Outcomes of the Initial Phase of an Adult Living vs Deceased Donor Liver Transplantation Program in a Low-Volume Transplant Cen-ter: Integration of Hepatobiliary and Transplant Surgery. Transplant. Proc. 2023, 55, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shingina, A.; Ziogas, I.A.; Vutien, P.; Uleryk, E.; Shah, P.S.; Renner, E.; Bhat, M.; Tinmouth, J.; Kim, J. Adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation in acute liver failure. Transplant. Rev. 2022, 36, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, G.; Muller, X.; Ruiz, M.; Collardeau-Frachon, S.; Boulanger, N.; Depaulis, C.; Antonini, T.; Dubois, R.; Mohkam, K.; Mabrut, J.Y. HOPE Mitigates Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Ex-Situ Split Grafts: A Comparative Study with Living Donation in Pediatric Liver Transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2024, 37, 12686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Naga, S.; Safwan, M.; Putchakayala, K.; Rizzari, M.; Collins, K.; Yoshida, A.; Schnickel, G.; Abouljoud, M. Prolonged Cold Ischemia Time as a Risk for Low Regeneration at the Early Phase After Living Donor Liver Transplantation. In Proceedings of the 2017 American Transplant Congress, Chicago, IL, USA, 29 April–3 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rela, M.; Rammohan, A. Patient and donor selection in living donor liver transplantation. Dig. Med. Res. 2020, 3, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.I.; Kim, K.H.; Hwang, S.; Ahn, C.S.; Moon, D.B.; Ha, T.Y.; Song, G.W.; Lee, S.G. Out-comes of 6000 living donor liver transplantation procedures: A pioneering experience at ASAN Med-ical Center. Updates Surg 2025, 77, 1777–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.T.; Testa, G. Living donor liver transplantation in the USA. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2016, 5, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.W.; Lee, S.G. Living donor liver transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2014, 19, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zeng, R.W.; Lim, W.H.; Tan, D.J.H.; Yong, J.N.; Fu, C.E.; Tay, P.; Syn, N.; Ong, C.E.Y.; Ong, E.Y.H.; et al. The incidence of adverse outcome in donors after living donor liver transplanta-tion: A meta-analysis of 60,829 donors. Liver Transplant. 2024, 30, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Name | Year | Country | Centers (Single or Multiple) | Study Design | Study Duration | Total Sample Size | LDLT Sample Size | DDLT Sample Size | Follow-Up Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ninomiya [8] | 2015 | Japan & USA (LDLT from Japan, DDLT from USA) | Multi-center | Retrospective Cohort | 2002–2010 | 495 | 133 | 362 | Median of 75 months (LDLT); 72 months (DDLT) |

| Al-Sebayel [9] | 2015 | KSA | Single | Retrospective Cohort | 2001–2013 | 491 | 222 | 269 | Median of 75 months (LDLT); 123 months (DDLT) |

| Hu [2] | 2015 | China | Multi-center | Retrospective Cohort | 1999–2009 | 6860 | 389 | 6471 | Median of 16.38 months (LDLT); 14.97 months (DDLT) |

| Samstein [10] | 2016 | USA | Multi-center | Prospective Observational | 1998–2009 | 1036 | 565 | 471 | Median of 57.6 months (LDLT); 50.28 months (DDLT) |

| Barbas [11] | 2017 | Canada | Single | Retrospective Cohort | 2000–2014 | 176 | 48 | 128 | Median of 52.9 months for both LDLT and DDLT |

| Chok [12] | 2017 | China | Single | Retrospective Cohort | 2005–2014 | 94 | 54 | 40 | Median of 77.4 months (LDLT); 55.4 months (DDLT) |

| Azoulay [13] | 2017 | France | Multi-center | Retrospective Cohort | 2000–2009 | 699 | 79 | 620 (BDLT) | Mean of 70.4 ± 64.3 months; 102.5 ± 16 months (LDLT) and 67.2 ± 160 months (BDLT)] |

| E. Kim [14] | 2017 | South Korea | Single | Retrospective Cohort | 2010–2014 | 185 | 109 | 76 | 12 years post-transplant or death for both LDLT and DDLT |

| J.M. Kim [15] | 2017 | Korea | Multi-center | Retrospective Cohort | 1999–2012 | 62 | 31 | 31 | Median of 36 months (LDLT); 18 months (DDLT) |

| Kwon [16] | 2017 | Korea | Single | Retrospective Cohort | 2000–2017 | 25 | 15 | 10 | N/A |

| Wong [17] | 2019 | China | Single | Retrospective Cohort | 1995–2014 | 130 | 65 | 65 | Median of 62 months for both LDLT and DDLT |

| Humar [18] | 2019 | USA | Single | Retrospective Cohort | 2009–2019 | 837 | 245 | 592 | Median of 33.5 months (LDLT); 53.8 months (DDLT) |

| Braun [19] | 2020 | USA | N/A (A2ALL cohort study) | Longitudinal Cohort (retrospective& prospective data) | 1998–2014 (retrospective); 2004–2009 (prospective) | 254 | 168 | 86 | N/A |

| Ziogas [20] | 2020 | USA | Multi-center (OPTN database) | Retrospective Cohort | 2002–2018 | 6911 | 912 | 5999 | N/A |

| Goto [21] | 2022 | Canada | Single | Retrospective Cohort | 2000–2019 | 2264 | 668 | 1596 | Median of 56.4 years for both LDLT and DDLT |

| Amara [22] | 2022 | USA | Multi-center | Prospective Observational | 2017–2019 | 1793 | 109 | 1684 | N/A |

| Lapisatepun [23] | 2024 | Thailand | Multi-center | Retrospective Cohort | 2014–2020 | 40 | 20 | 20 | N/A |

| Study Name | Year | Recipient Age (Years) | MELD Score | Recipient BMI | Recipient Male: Female | All Recipient Male % | Diagnosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDLT | DDLT | LDLT | DDLT | LDLT | DDLT | LDLT | DDLT | ||||

| Ninomiya [8] | 2015 | Mean 57.6 ± 7.1 | Mean 58.3 ± 7.4 | Mean 11.9 ± 4.9 | Mean 15.9 ± 8.3 | Mean 23.9 ± 3.1 | Mean 27.6 ± 5.4 | 78:55 | 285:77 | 73.3% | HCC |

| Al-Sebayel [9] | 2015 | Median 53 (15–80) | Median 52 (15–76) | 18 | 16 | N/A | N/A | 139:83 | 153:116 | 59.5% | Mix |

| Hu [2] | 2015 | Mean 48.05 ± 8.65 | Mean 50.09 ± 9.43 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 57:52 | 1135:549 | 66.3% | HCC |

| Samstein [10] | 2016 | Mean 51.0 ± 10.9 | Mean 52.2 ± 10.4 | Mean 15.2 ± 5.7 | Mean 20.3 ± 8.9 | Mean 26.5 ± 5.2 | Mean 26.7 ± 4.9 | 311:254 | 285:186 | 57.52% | Mix |

| Barbers [11] | 2017 | Mean 54.7 ± 9.4 | Mean 56.7 ± 9.3 | Mean 17.8 ± 8.7 | Mean 21.8 ± 10.3 | Mean 29.7 ± 4.9 | Mean 30.5 ± 6.4 | 35:13 | 87:41 | 69.3% | Mix |

| Chok [12] | 2017 | Mean 51± 12 | Mean 51± 10.8 | Mean 40± 1.3 | Mean 39± 1.3 | N/A | N/A | 42:12 | 34:6 | 80.85% | Mix |

| Azoulay [13] | 2017 | Mean 54.3 ± 7.4 | Mean 56.0 ± 7.8 | Mean 14.7 ± 7.5 | Mean 12.4 ± 6.5 | N/A | N/A | 65:14 | 677:106 | 86.1% | HCC |

| E. Kim [14] | 2017 | Mean 52.0 ± 8.5 | Mean 53.1 ± 11.0 | Mean 12.5 ± 8.3 | Mean 24.9 ± 11.7 | N/A | N/A | 81:28 | 50:26 | 70.8% | Mix |

| J.M. Kim [15] | 2017 | N/A | N/A | Median 20 (11–40) | Median 20 (8–38) | N/A | N/A | 21:10 | 21:10 | 67.7% | Mix |

| Kwon [16] | 2017 | Mean 71.7 ± 2.4 | Mean 71.9 ± 1.9 | Mean 14.1 ± 10.0 | Mean 26.6 ± 8.9 | N/A | N/A | 11:4 | 8:2 | 76% | Mix |

| Wong [17] | 2019 | Median 55 (40–73) | Median 57 (41–67) | Median 11 (6–59) | Median 12 (6–37) | N/A | N/A | 54:11 | 54:11 | 83.1% | HCC |

| Humar [18] | 2019 | Mean 56 | Mean 56 | Mean 16 | Mean 22 | Mean 28.4 | Mean 29.7 | 145:100 | 414:178 | 67% | Mix |

| Braun [19] | 2020 | Median 53 (48–59) | N/A | Median 15 (13–19) | N/A | Median 26.2 (23.2–29.5) | N/A | 119:49 | N/A | 70.8% | ALD |

| Ziogas [20] | 2020 | Mean 46.6 ± 13.9 | Calculated mean 50.42 ± 13.19 | Mean 15.2 ± 5.6 | Calculated mean 23.08 ± 9.47 | N/A | N/A | 427:485 | 2857:3142 | 47.52% | CLD |

| Goto [21] | 2022 | Median 54 (47–61) | Median 57 (50–62) | Median 15 (12–20) | Median 16 (11–25) | Median 27 (23–29) | Median 28 (24–30) | 402:266 | 1181:415 | 74% (DDLT); 60.2% (LDLT) | Mix |

| Amara [22] | 2022 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 57:52 | 1135:549 | 66.3% | Mix |

| Lapisatepun [23] | 2024 | Mean 54.7 ± 11.7 | Mean 48.8 ± 14.3 | Median 14.5 (12–23.5) | Median 14.5 (7.5–22.5) | Mean 23.0 ± 2.6 | Mean 24.3 ± 4.3 | 14:6 | 14:7 | 70% | Mix |

| Study | Year | Total Score (out of 32) | Reporting | External Validity | Internal Validity Bias | Internal Validity Confounding | Power | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ninomiya [8] | 2015 | 21 | 10/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 3/6 | 0/1 | Moderate |

| Al-Sebayel [9] | 2015 | 19 | 7/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 4/6 | 0/1 | Moderate |

| Hu [2] | 2015 | 21 | 9/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 4/6 | 0/1 | Moderate |

| Samstein [10] | 2016 | 22 | 10/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 4/6 | 0/1 | High |

| Barbers [11] | 2017 | 21 | 9/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 4/6 | 0/1 | Moderate |

| Chok [12] | 2017 | 22 | 10/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 4/6 | 0/1 | High |

| Azoulay [13] | 2017 | 22 | 9/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 5/6 | 0/1 | High |

| E. Kim [14] | 2017 | 21 | 9/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 4/6 | 0/1 | Moderate |

| J.M. Kim [15] | 2017 | 22 | 10/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 4/6 | 0/1 | High |

| Kwon [16] | 2017 | 22 | 10/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 4/6 | 0/1 | High |

| Wong [17] | 2019 | 22 | 10/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 4/6 | 0/1 | High |

| Humar [18] | 2019 | 20 | 10/11 | 3/3 | 4/7 | 3/6 | 0/1 | Moderate |

| Braun [19] | 2020 | 19 | 9/11 | 2/3 | 5/7 | 3/6 | 0/1 | Moderate |

| Ziogas [20] | 2020 | 19 | 8/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 3/6 | 0/1 | Moderate |

| Goto [21] | 2022 | 24 | 10/11 | 3/3 | 6/7 | 5/6 | 0/1 | High |

| Amara [22] | 2022 | 23 | 10/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 5/6 | 0/1 | High |

| Lapesatepun [23] | 2024 | 21 | 9/11 | 3/3 | 5/7 | 4/6 | 0/1 | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rashid, B.; Naga, M.; Kobryń, K.; Grąt, M. Comparative Outcomes of Living and Deceased Donor Liver Transplantation in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010241

Rashid B, Naga M, Kobryń K, Grąt M. Comparative Outcomes of Living and Deceased Donor Liver Transplantation in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):241. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010241

Chicago/Turabian StyleRashid, Bestun, Mohammed Naga, Konrad Kobryń, and Michał Grąt. 2026. "Comparative Outcomes of Living and Deceased Donor Liver Transplantation in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010241

APA StyleRashid, B., Naga, M., Kobryń, K., & Grąt, M. (2026). Comparative Outcomes of Living and Deceased Donor Liver Transplantation in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010241