Clinical Outcomes of Arthroscopic Treatment for Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex Lesions in Adolescent Elite Athletes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

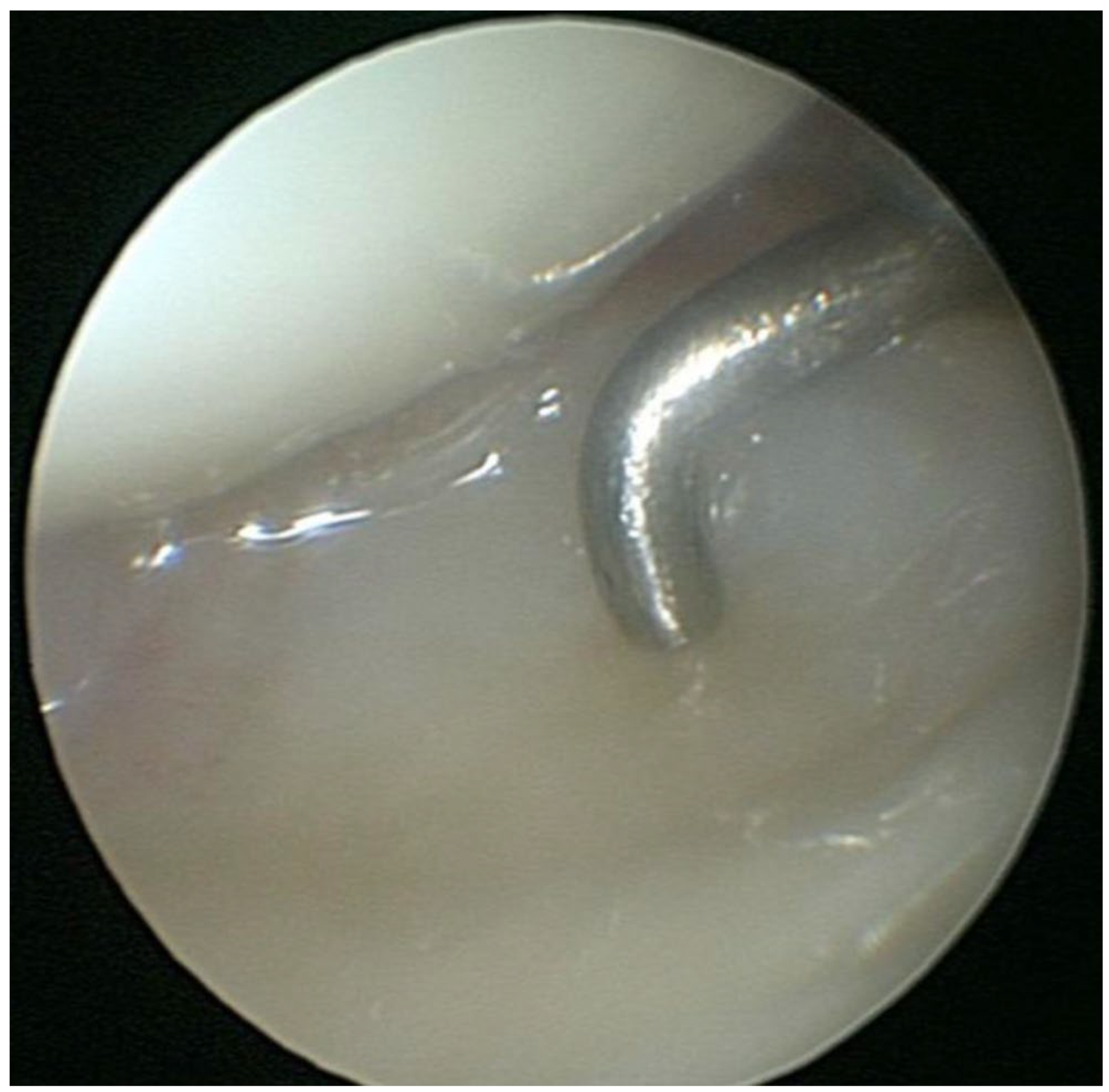

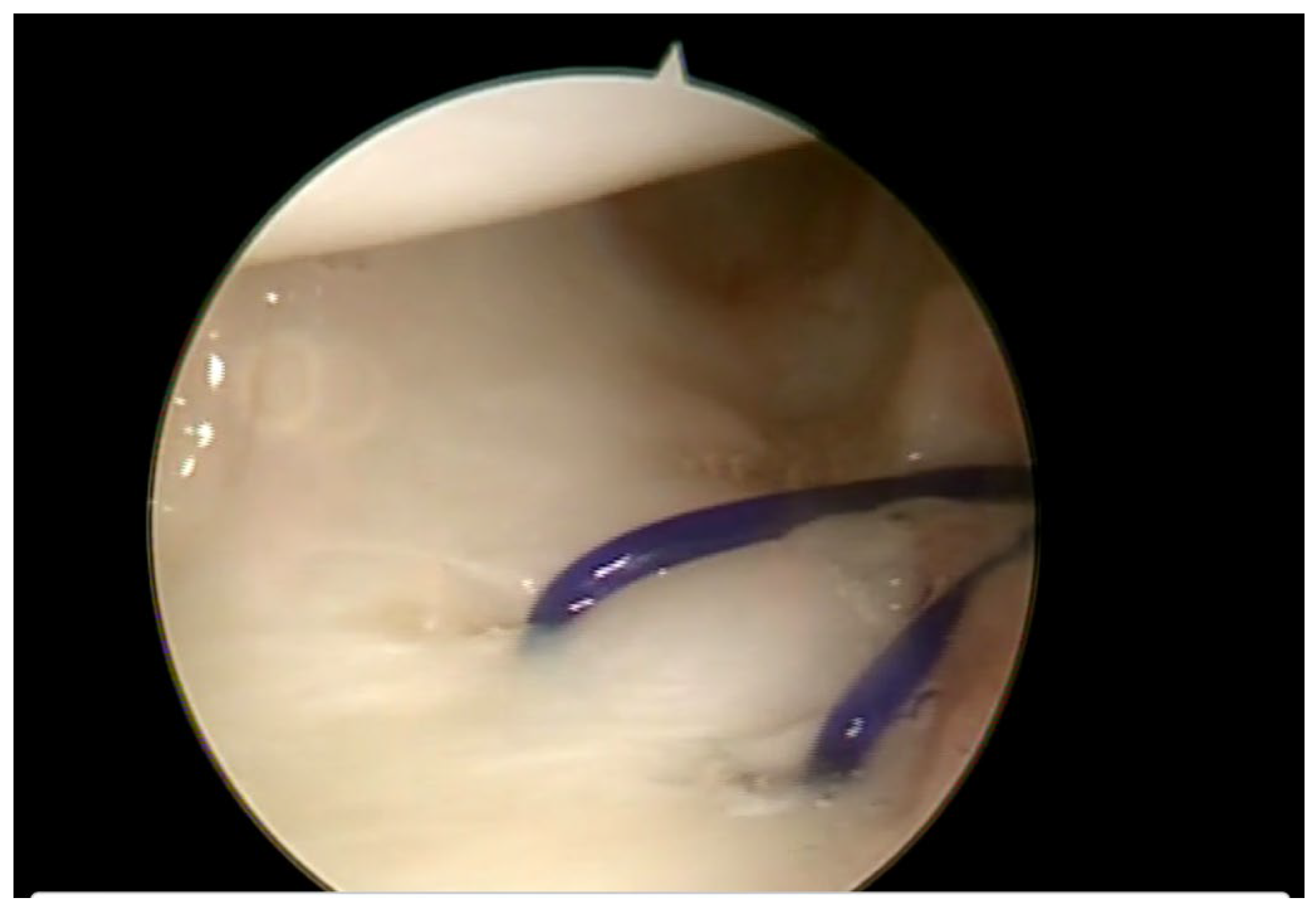

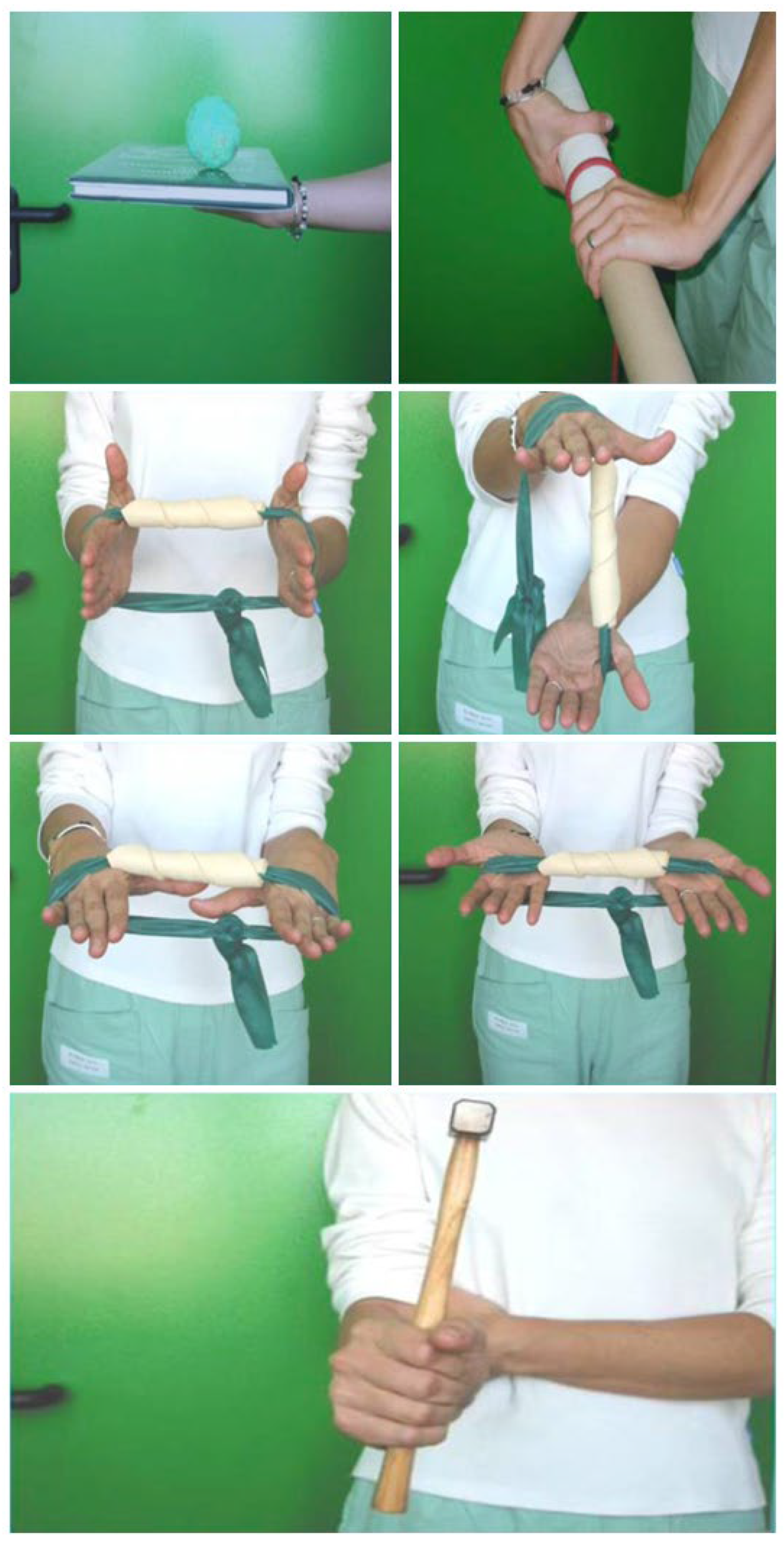

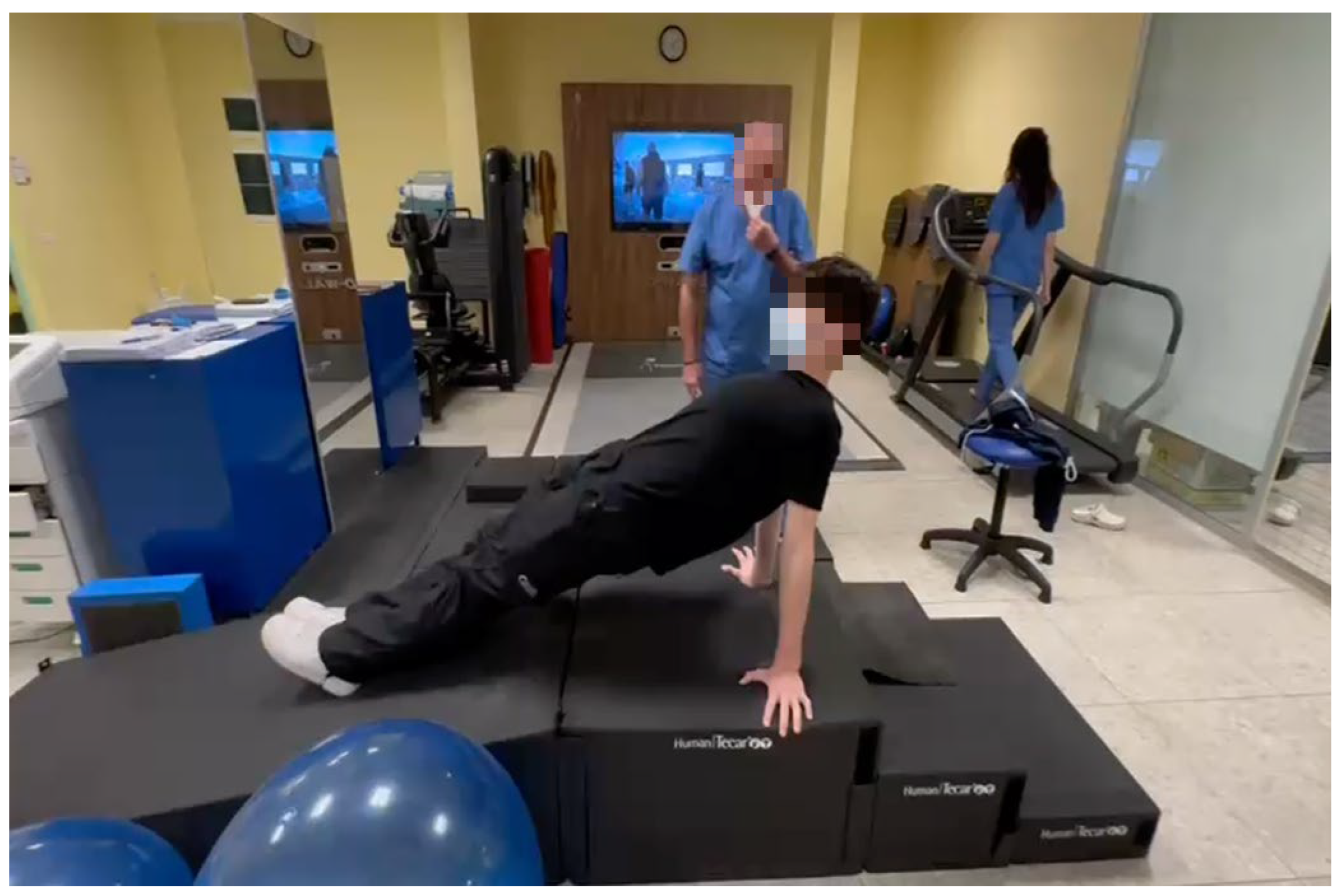

2.2. Treatment

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NRS | Numeric Rating Scale |

| ROM | Range of Motion |

| DASH | Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

| TFCC | Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex |

| DRUJ | Distal Radioulnar Joint |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

References

- Casadei, K.; Kiel, J. Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537055/ (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Pace, V.; Bronzini, F.; Novello, G.; Mosillo, G.; Braghiroli, L. Review and update on the management of triangular fibrocartilage complex injuries in professional athletes. World J. Orthop. 2024, 15, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, J.H.; Wiedrich, T.A. Triangular fibrocartilage complex injuries in the elite athlete. Hand Clin. 2012, 28, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishman, F.G.; Barber, J.; Lourie, G.M.; Peljovich, A.E. Outcomes of Operative Treatment of Triangular Fibrocartilage Tears in Pediatric and Adolescent Athletes. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2018, 38, e618–e622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plöger, M.M.; Kabir, K.; Friedrich, M.J.; Welle, K.; Burger, C. Ulnar-sided wrist pain in sports: TFCC lesions and fractures of the hook of the hamate bone as uncommon diagnosis. Der Unfallchirurg 2015, 118, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, A.K.; Chang, D.; Plate, A.M. Triangular fibrocartilage complex tears: A review. Bull. NYU Hosp. Jt. Dis. 2006, 64, 114–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Nho, J.-H.; Jung, K.J.; Yun, K.; Kim, Y.H.; Yoon, H.-K. Traumatic Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex Injuries and Instability of the Distal Radioulnar Joint. J. Korean Orthop. Assoc. 2017, 52, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, S.; Cozzolino, R.; Luchetti, R.; Cazzoletti, L. Comparison between MRI and Arthroscopy of the Wrist for the Assessment of Posttraumatic Lesions of Intrinsic Ligaments and the Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex. J. Wrist Surg. 2021, 11, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.H.; Haddad, R.G. Radiocarpal arthroscopy and arthrography in the diagnosis of ulnar wrist pain. Arthroscopy 1986, 2, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterman, A.L. Arthroscopic debridement of triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. Arthroscopy 1990, 6, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.K. Triangular fibrocartilage disorders: Injury patterns and treatment. Arthroscopy 1990, 6, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robba, V.; Fowler, A.; Karantana, A.; Grindlay, D.; Lindau, T. Open Versus Arthroscopic Repair of 1B Ulnar-Sided Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex Tears: A Systematic Review. Hand 2020, 15, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, S.; Grill, F.; Girsch, W. Wrist arthroscopy in children and adolescents: A single surgeon experience of thirty-four cases. Int. Orthop. 2012, 36, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr, S.; Zechmann, U.; Ganger, R.; Girsch, W. Clinical experience with arthroscopically-assisted repair of peripheral triangular fibrocartilage complex tears in adolescents--technique and results. Int. Orthop. 2015, 39, 1571–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geissler, W.B. Arthroscopic management of scapholunate instability. J. Wrist Surg. 2013, 2, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugstvedt, J.R.; Søreide, E. Arthroscopic Management of Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex Peripheral Injury. Hand Clin. 2017, 33, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummesson, C.; Atroshi, I.; Ekdahl, C. The disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) outcome questionnaire: Longitudinal construct validity and measuring self-rated health change after surgery. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2003, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzei, A.; Luchetti, R. Foveal TFCC tear classification and treatment. Hand Clin. 2011, 27, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachinger, F.; Farr, S. Arthroscopic Treatment Results of Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex Tears in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kox, L.S.; Kuijer, P.P.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.; Maas, M.; Frings-Dresen, M.H. Prevalence, incidence and risk factors for overuse injuries of the wrist in young athletes: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.K.; Åhlén, M.; Andernord, D. Open versus arthroscopic repair of the triangular fibrocartilage complex: A systematic review. J. Exp. Orthop. 2018, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfanner, S.; Diaz, L.; Ghargozloo, D.; Denaro, V.; Ceruso, M. TFCC Lesions in Children and Adolescents: Open Treatment. J. Hand Surg. Asian-Pac. Vol. 2018, 23, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, Z.S.; Davelaar, C.M.F.; Kiebzak, G.M.; Edmonds, E.W. Treatment Decisions in Pediatric Sports Medicine: Do Personal and Professional Bias Affect Decision-Making? Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2021, 9, 23259671211046258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.J.; Murray, M.M.; Christino, M.A. Clinical Approach in Youth Sports Medicine: Patients’ and Guardians’ Desired Characteristics in Sports Medicine Surgeons. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2019, 27, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Preoperation | Postoperation | p-Value | T-Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRS | 6.9 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 0.7 | <0.001 * | 25.76 |

| Grip strength (kg) | 26.3 ± 6.9 | 40.8 ± 5.6 | <0.001 * | −25.78 |

| ROM (flexion; °) | 71.5 ± 8.0 | 87.7 ± 4.7 | <0.001 * | −10.43 |

| ROM (extension; °) | 64.9 ± 8.0 | 82.6 ± 6.9 | <0.001 * | −10.26 |

| ROM (pronosupination; °) | 132.2 ± 18.2 | 175.5 ± 5.1 | <0.001 * | −14.10 |

| DASH | 45.1 ± 4.4 | 6.0 ± 2.2 | <0.001 * | 42.74 |

| Preoperation | Postoperation | p-Value | χ2 Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballottement test (+/−), n | 24/0 | 4/20 | <0.001 * | 34.29 |

| Waiter’s test (+/−), n | 19/5 | 3/21 | <0.001 * | 21.48 |

| Piano key test (+/−), n | 20/4 | 5/19 | <0.001 * | 18.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lombardo, M.D.M.; Chang, M.C.; Pegoli, L. Clinical Outcomes of Arthroscopic Treatment for Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex Lesions in Adolescent Elite Athletes. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010234

Lombardo MDM, Chang MC, Pegoli L. Clinical Outcomes of Arthroscopic Treatment for Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex Lesions in Adolescent Elite Athletes. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):234. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010234

Chicago/Turabian StyleLombardo, Michele Davide Maria, Min Cheol Chang, and Loris Pegoli. 2026. "Clinical Outcomes of Arthroscopic Treatment for Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex Lesions in Adolescent Elite Athletes" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010234

APA StyleLombardo, M. D. M., Chang, M. C., & Pegoli, L. (2026). Clinical Outcomes of Arthroscopic Treatment for Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex Lesions in Adolescent Elite Athletes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010234