The Influence of PAR 1 and Endothelin 1 on the Course of Specific Kidney Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Clinical Data

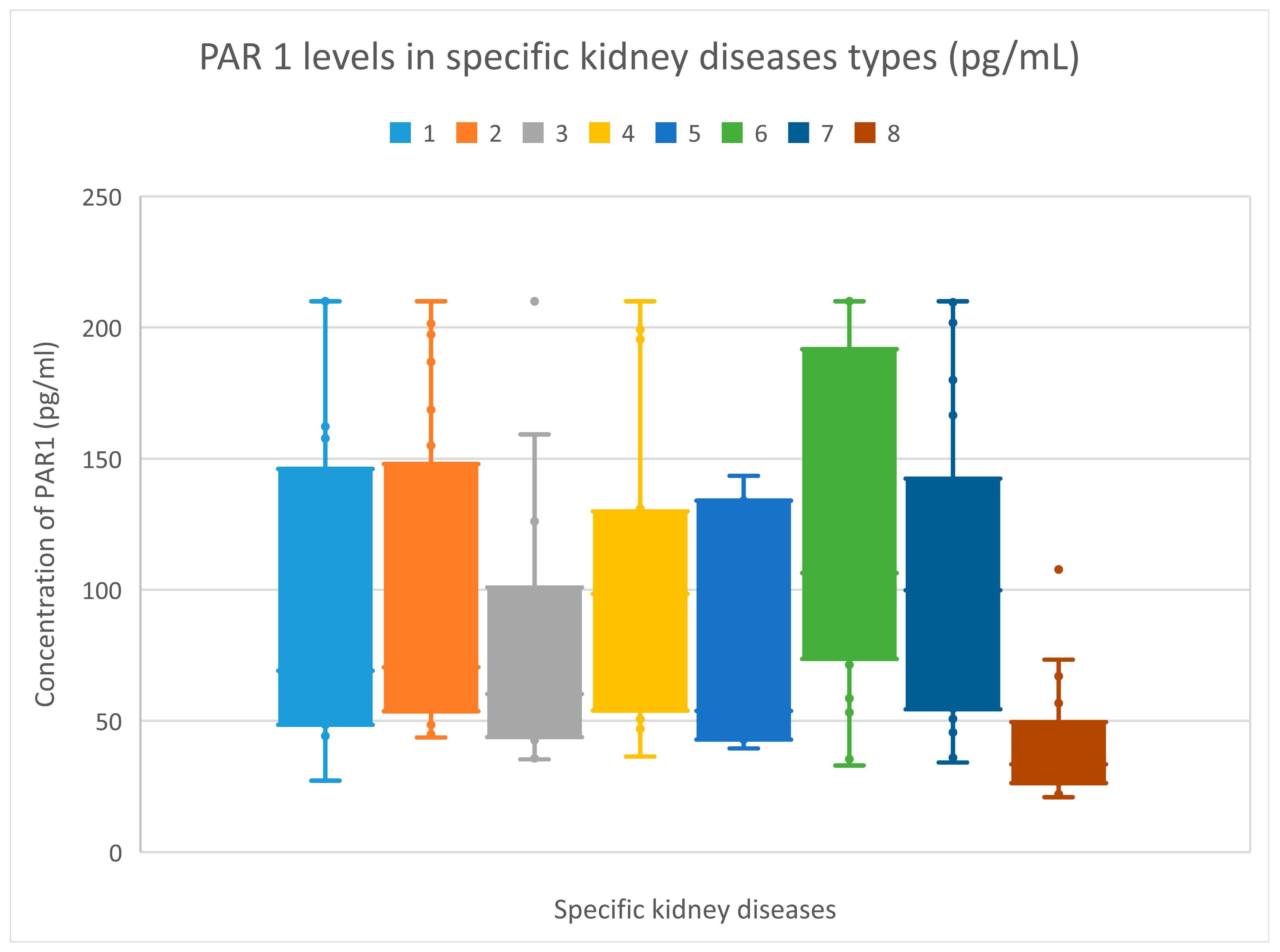

3.2. PAR 1 Evaluation Results

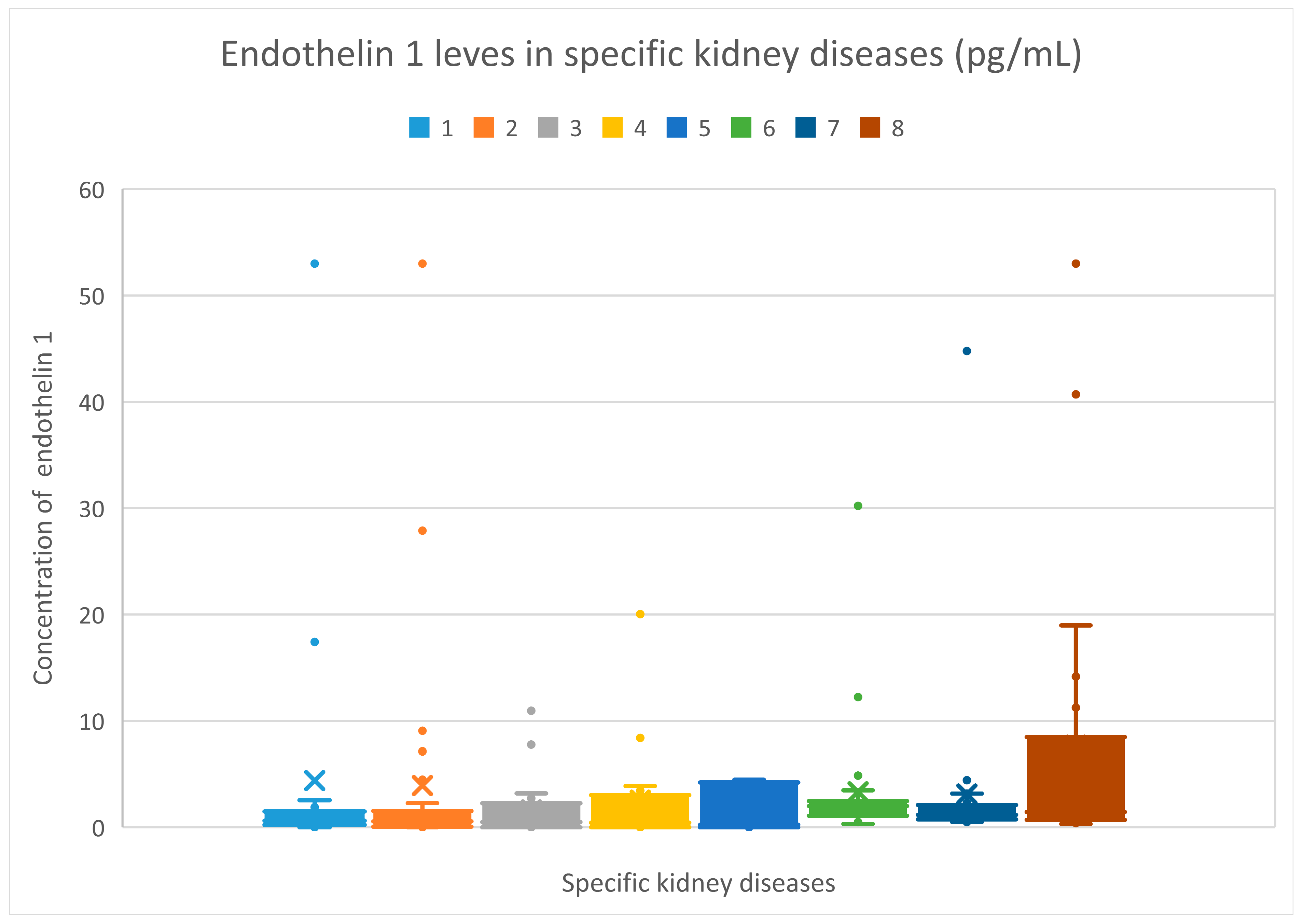

3.3. Endothelin 1 Evaluation Results

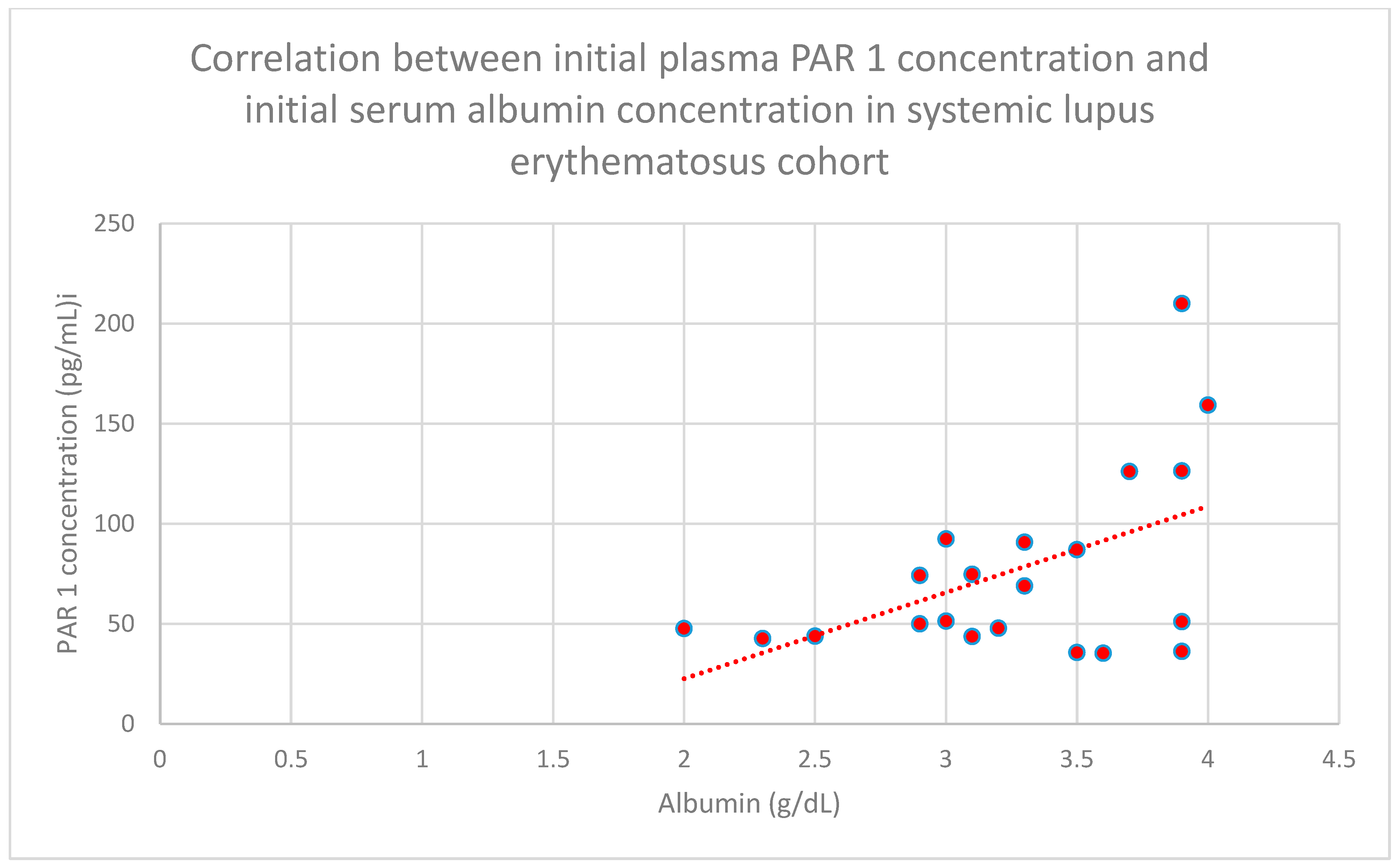

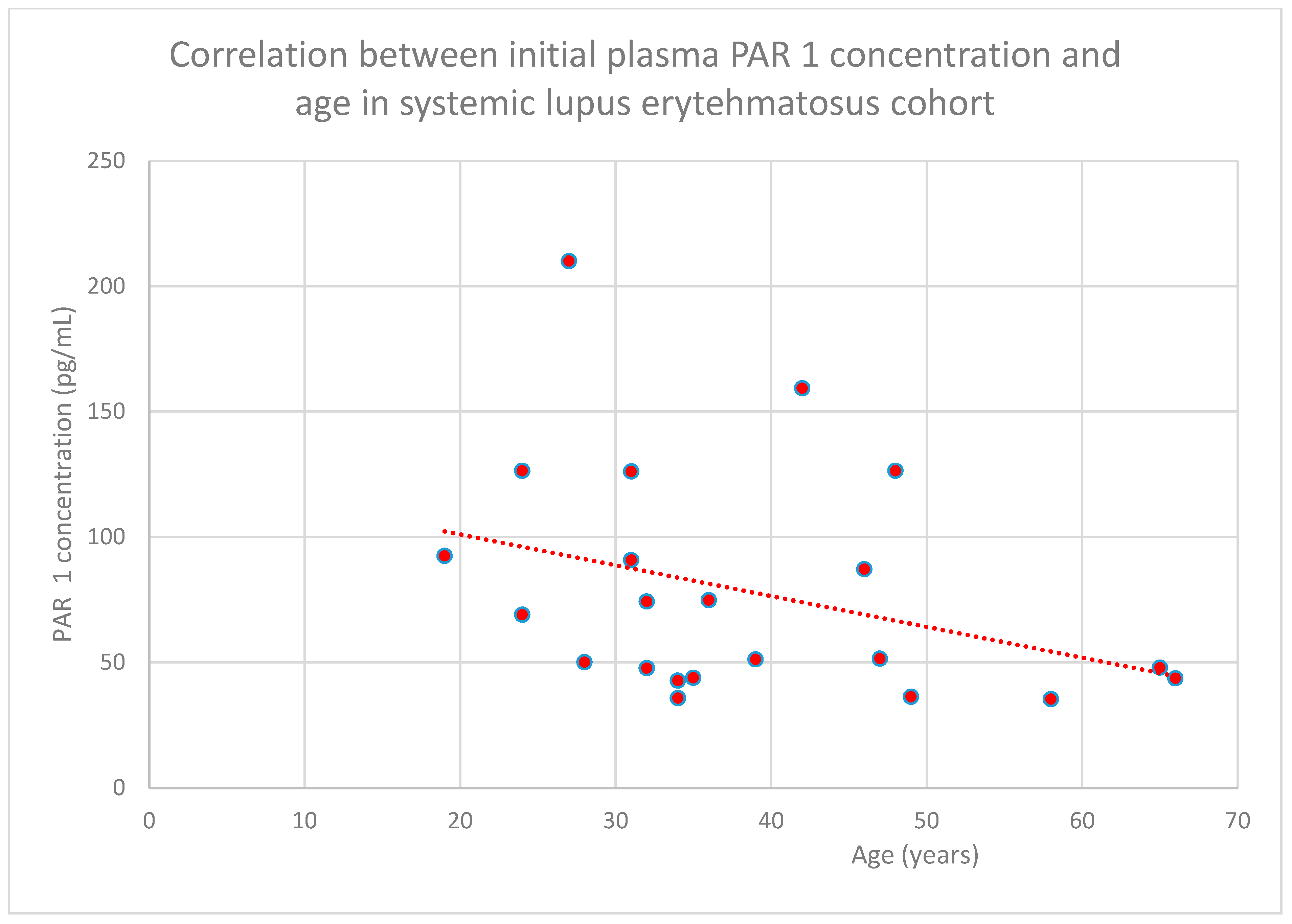

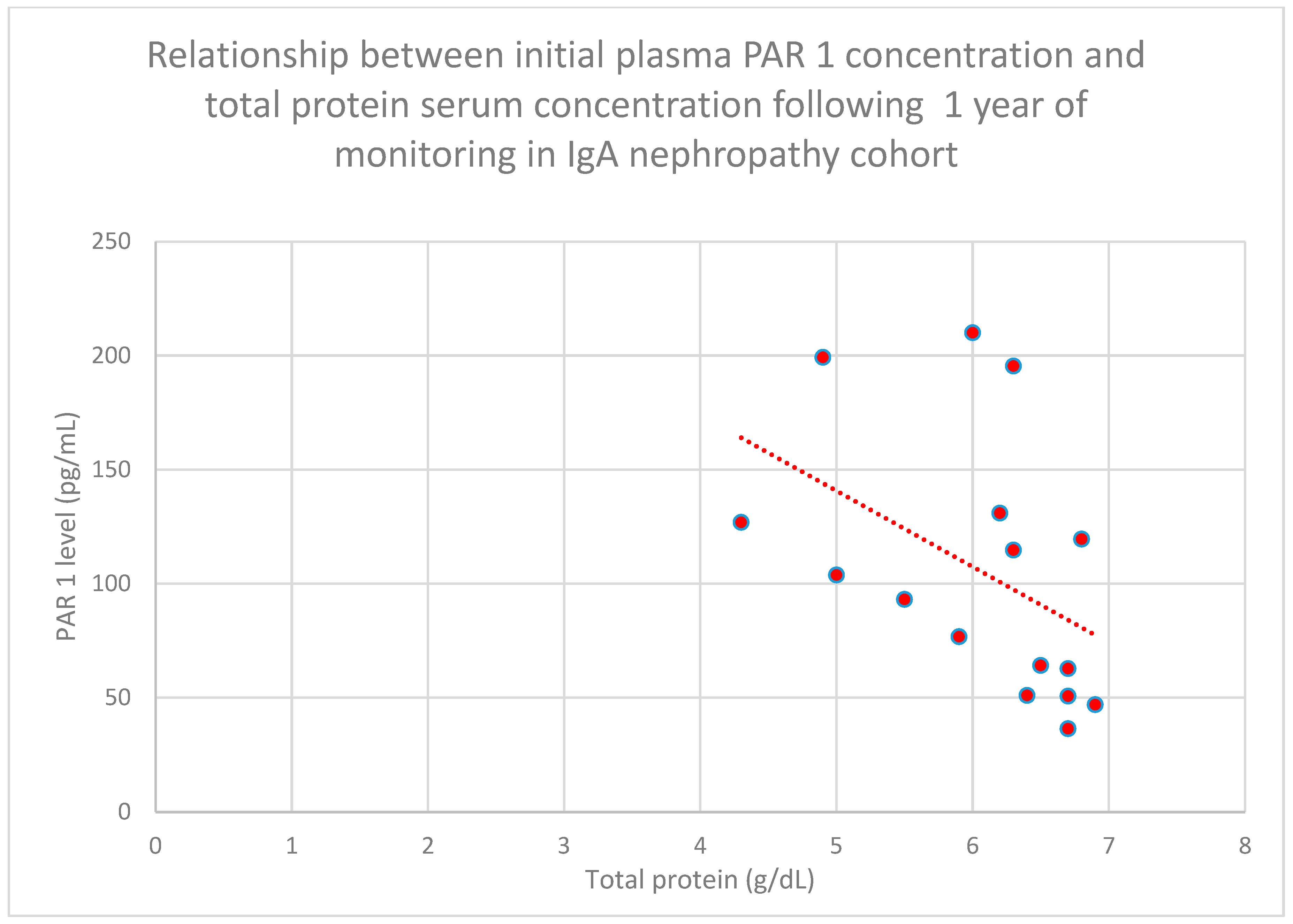

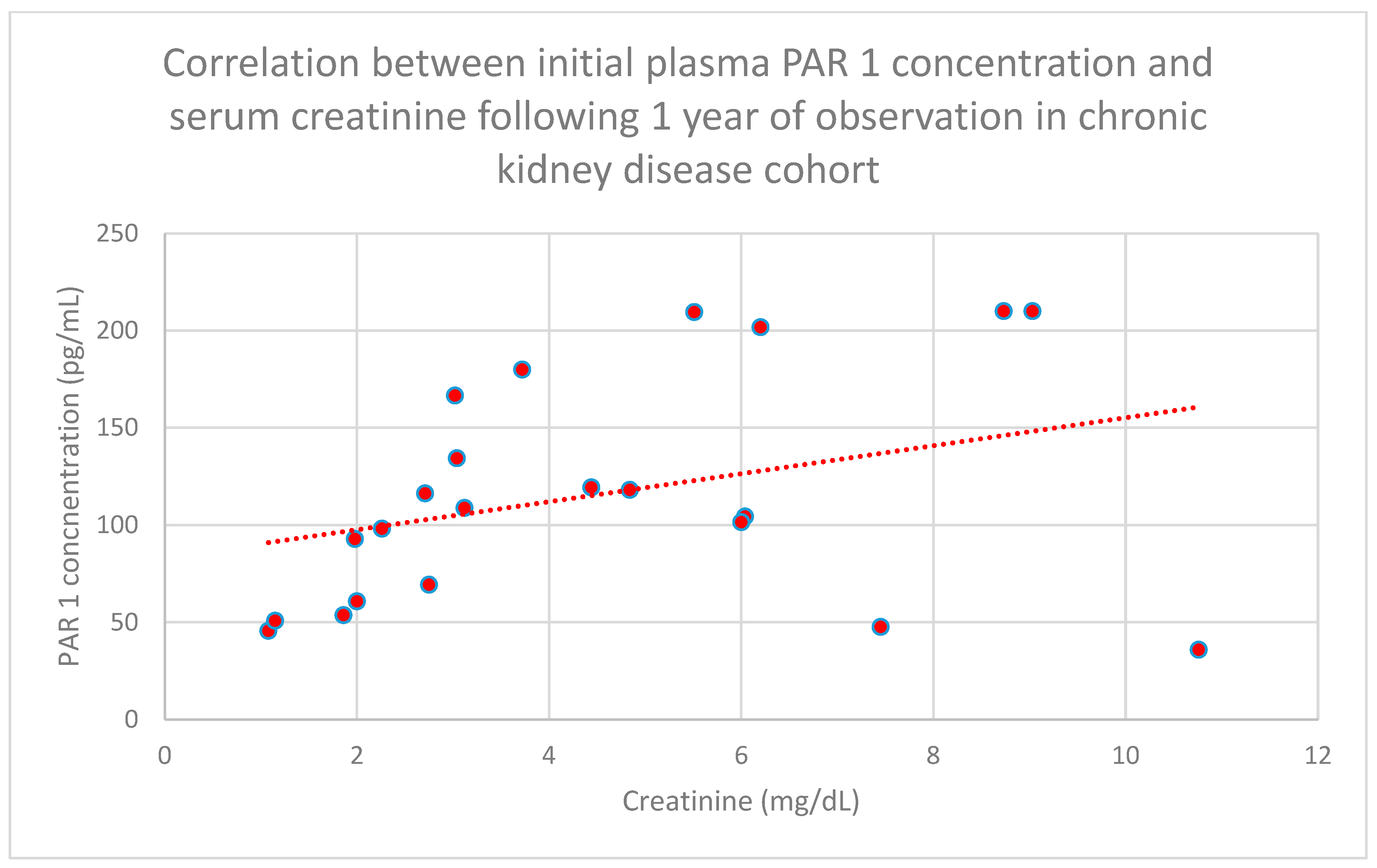

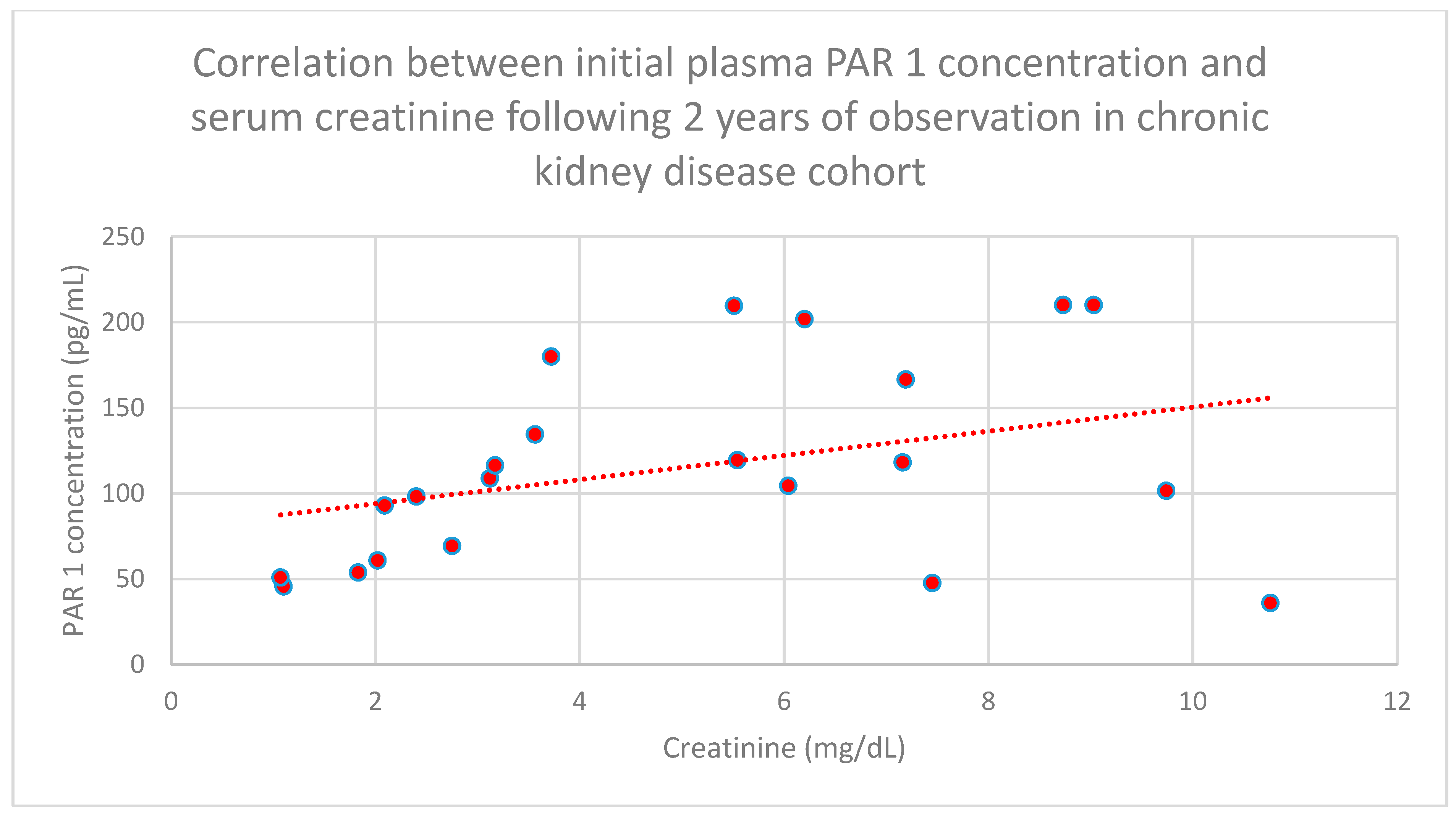

3.4. Relationship Between Clinical Patient Data and PAR 1 Levels

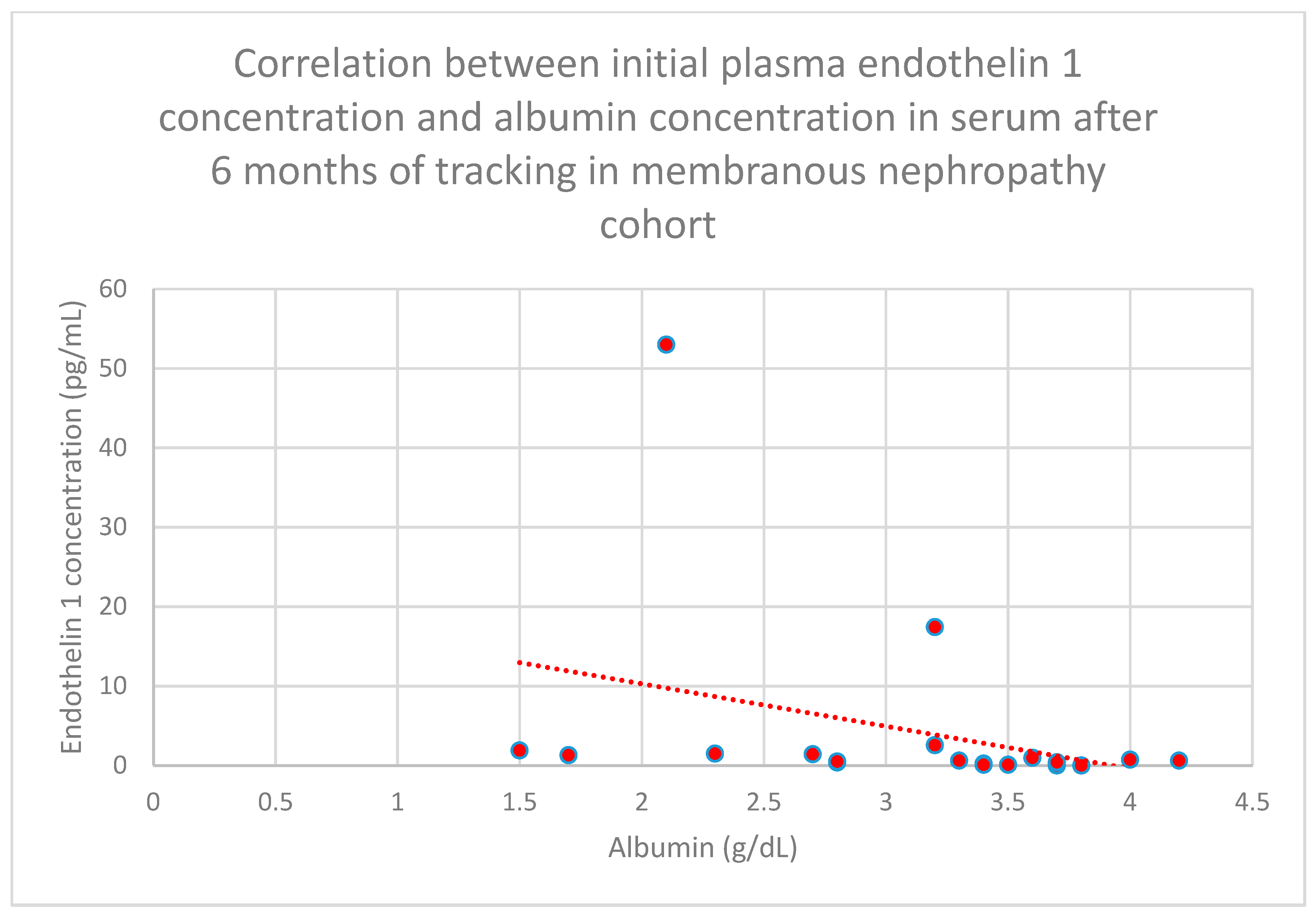

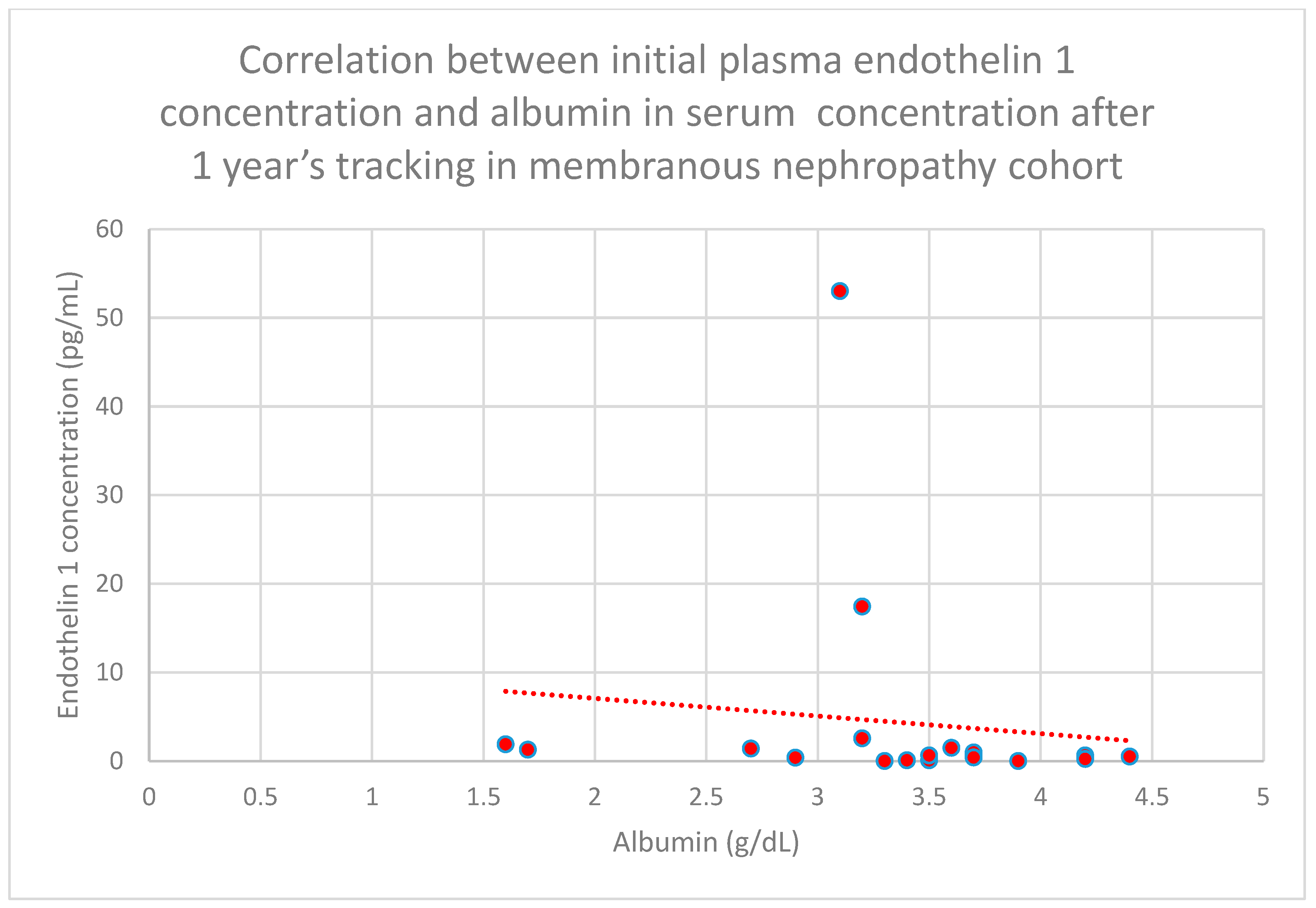

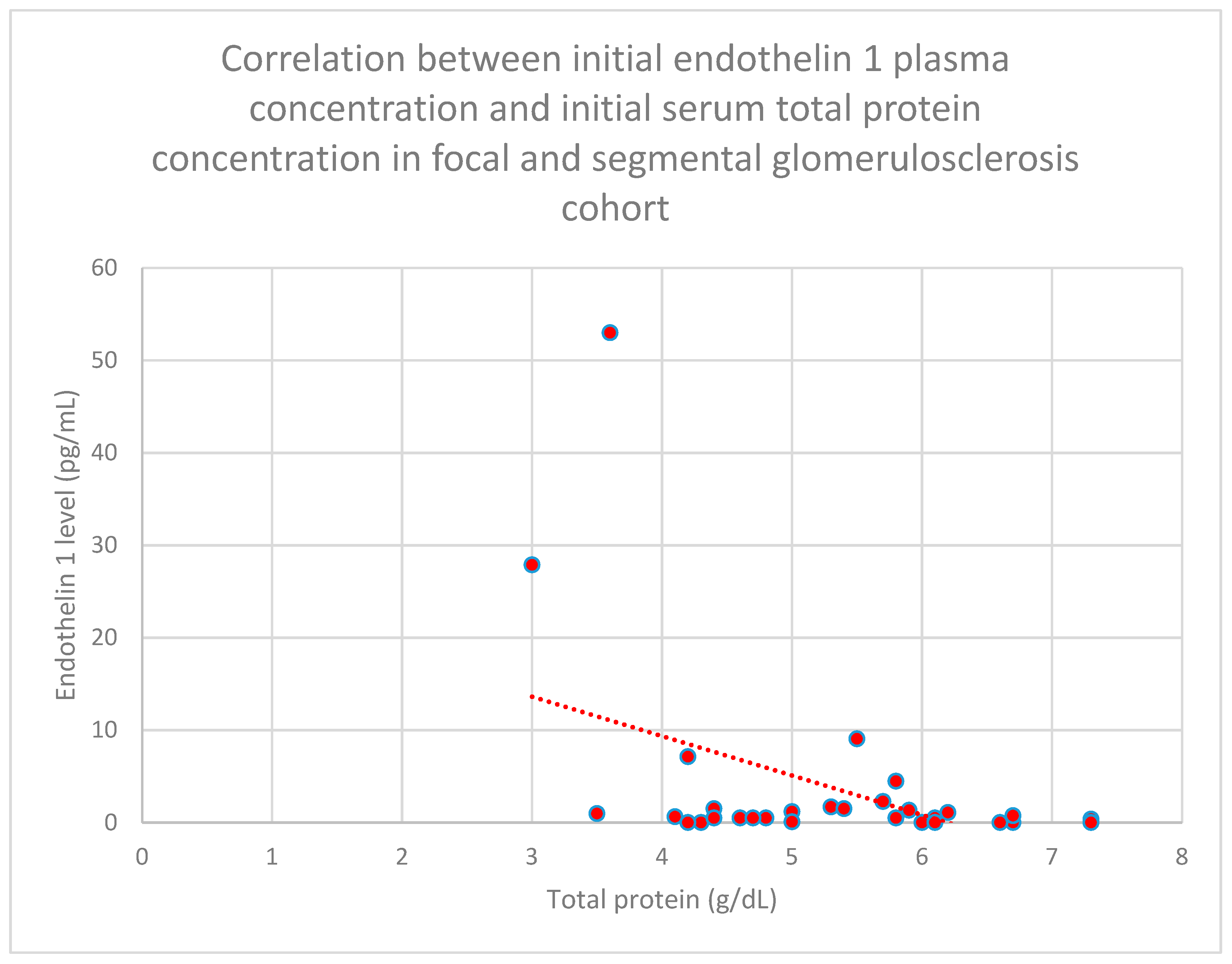

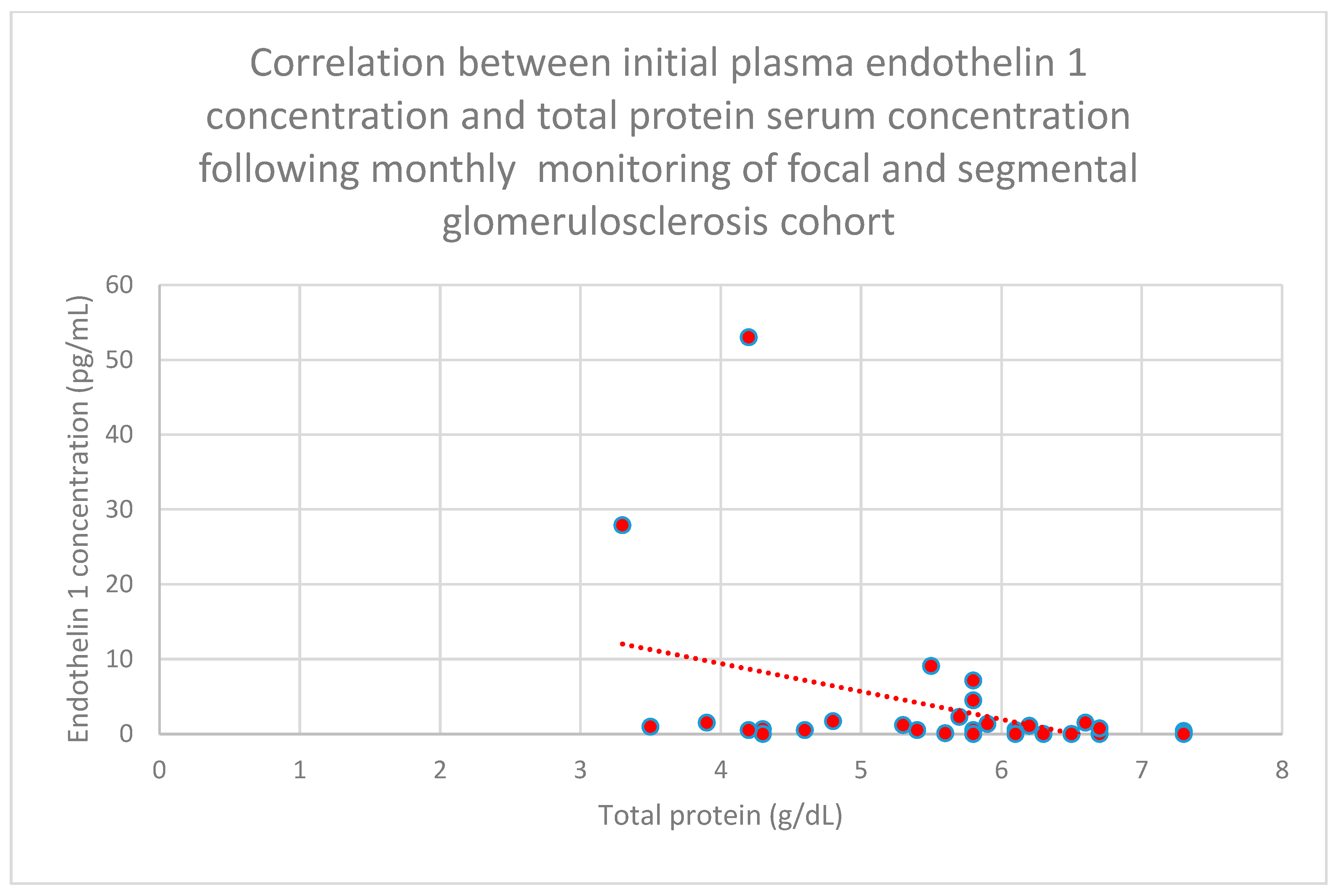

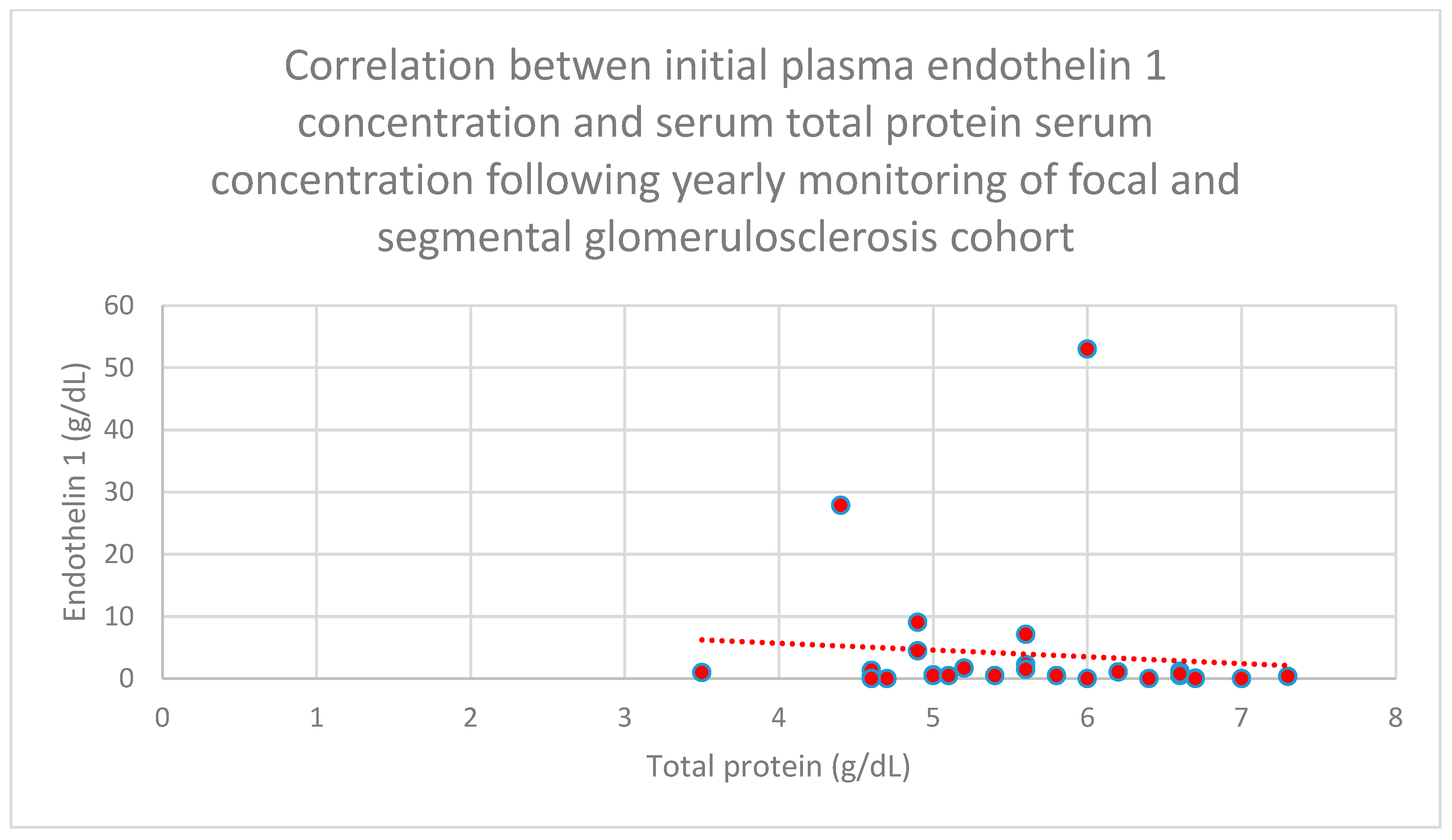

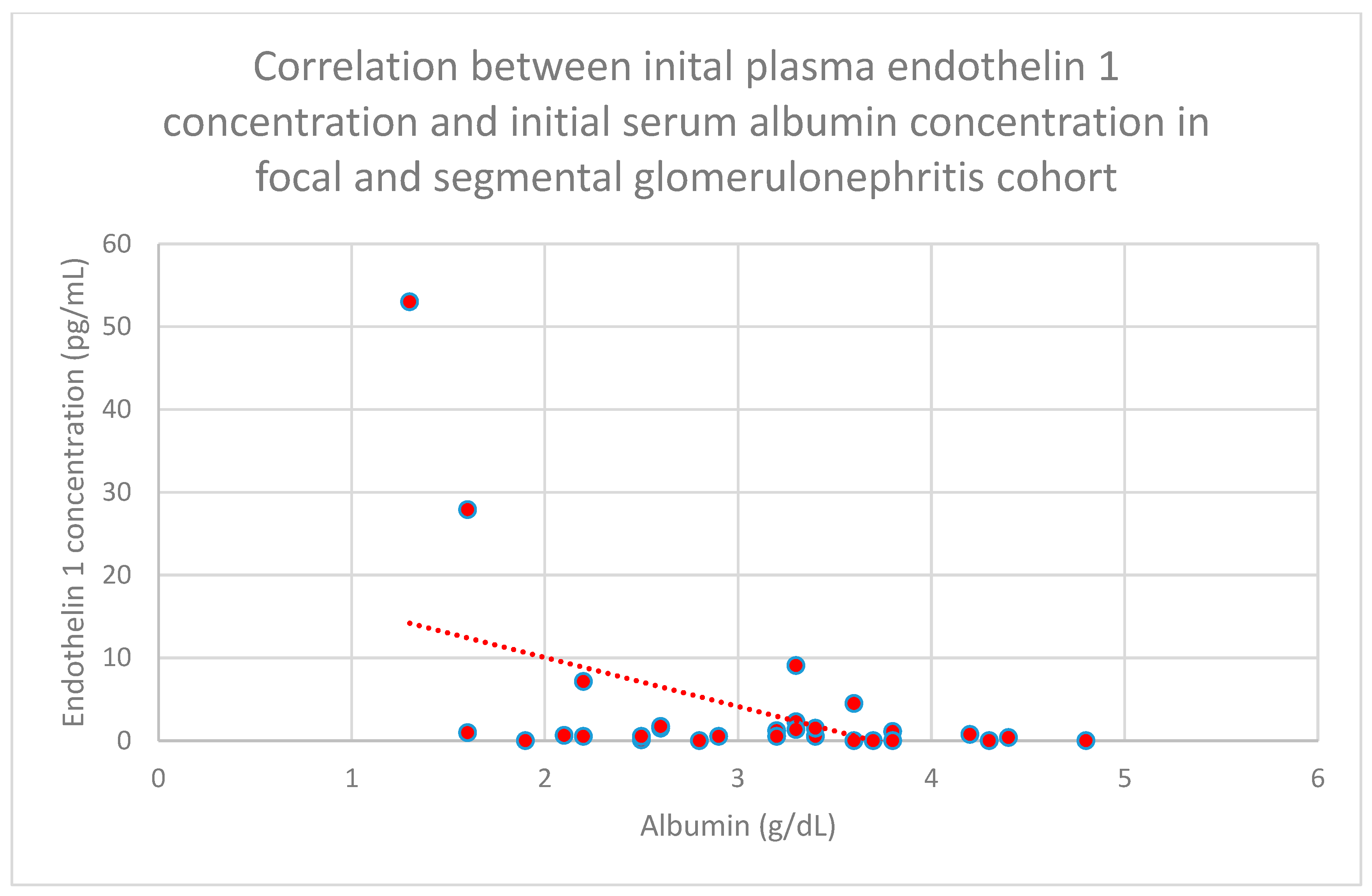

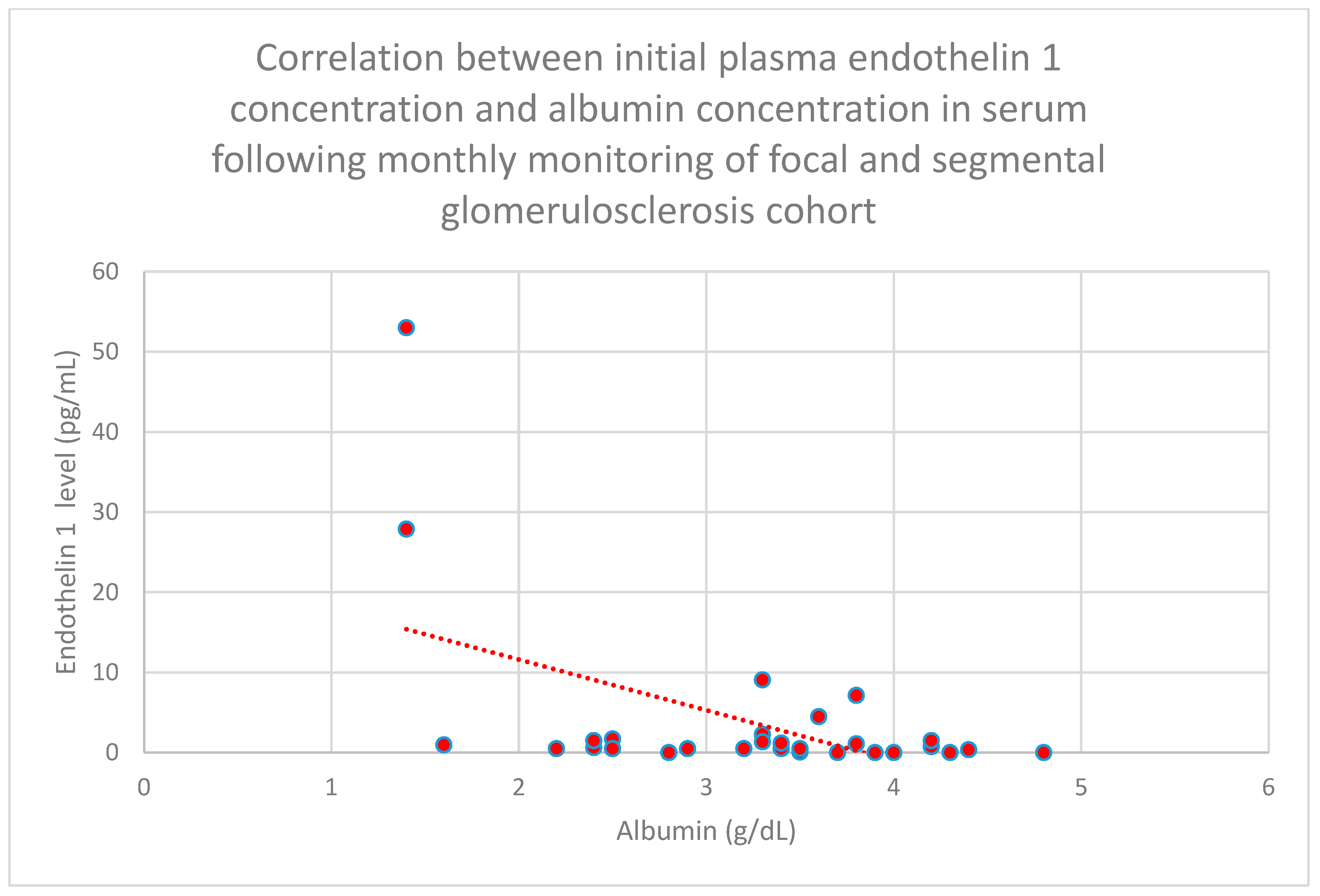

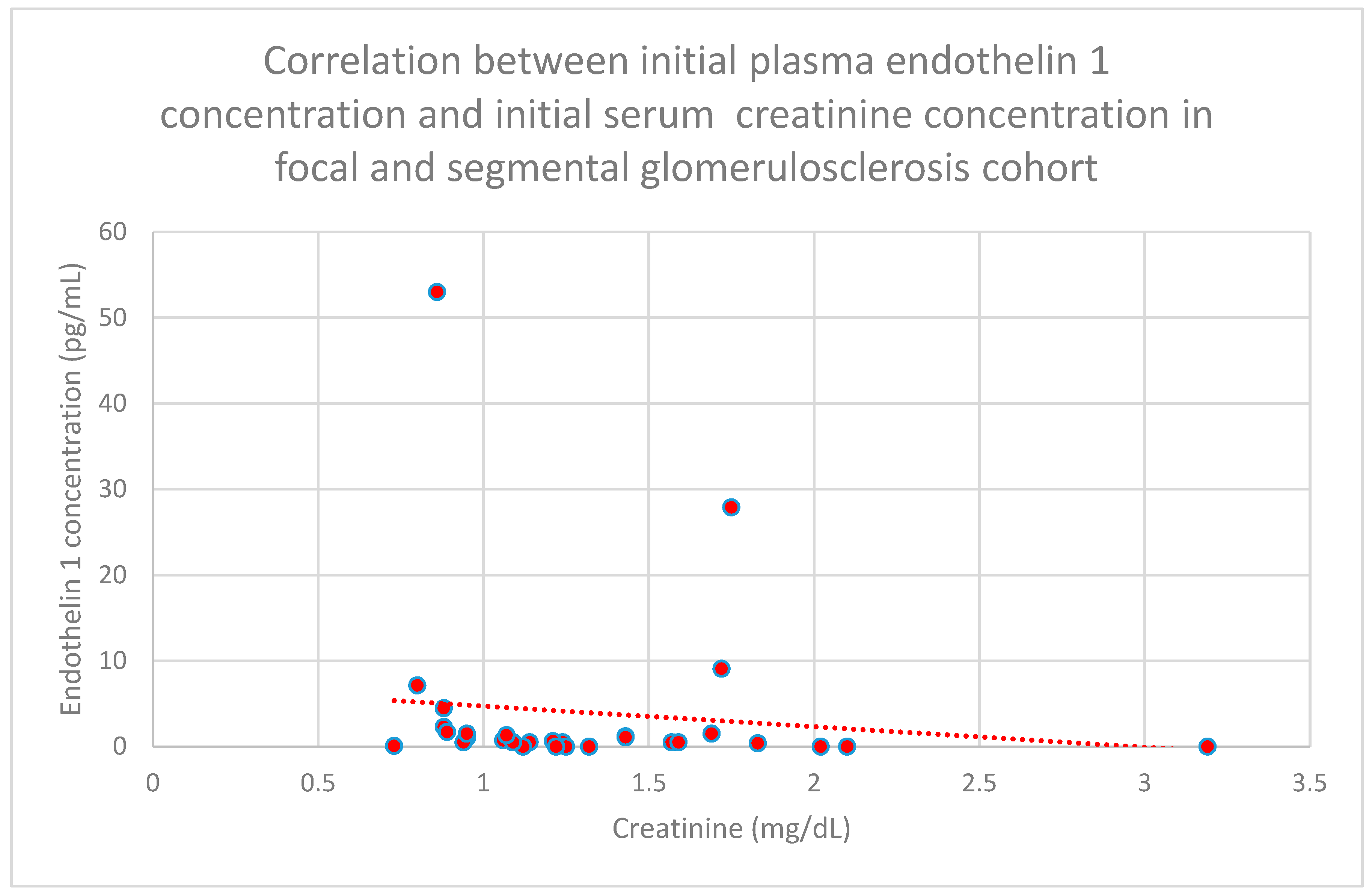

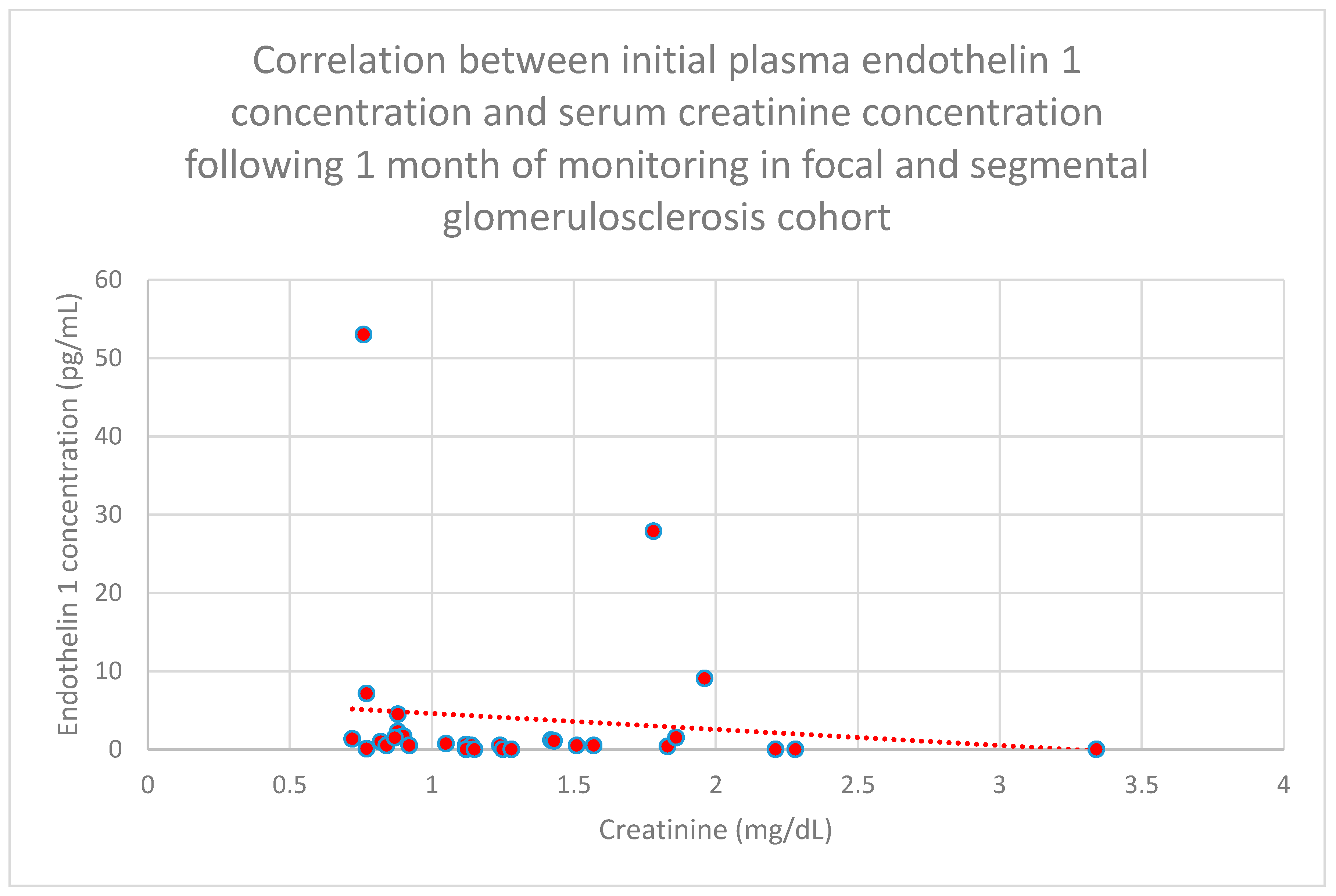

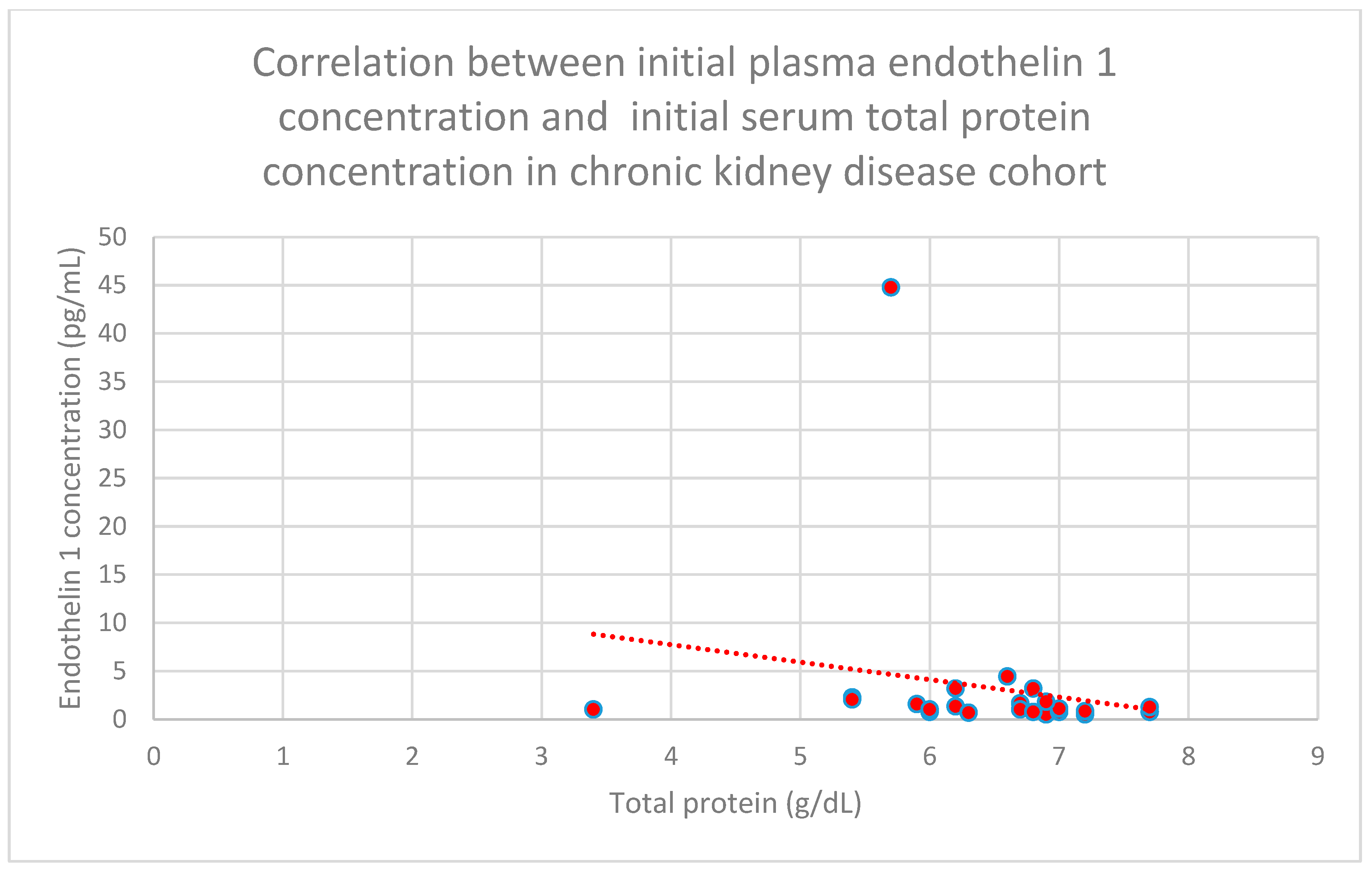

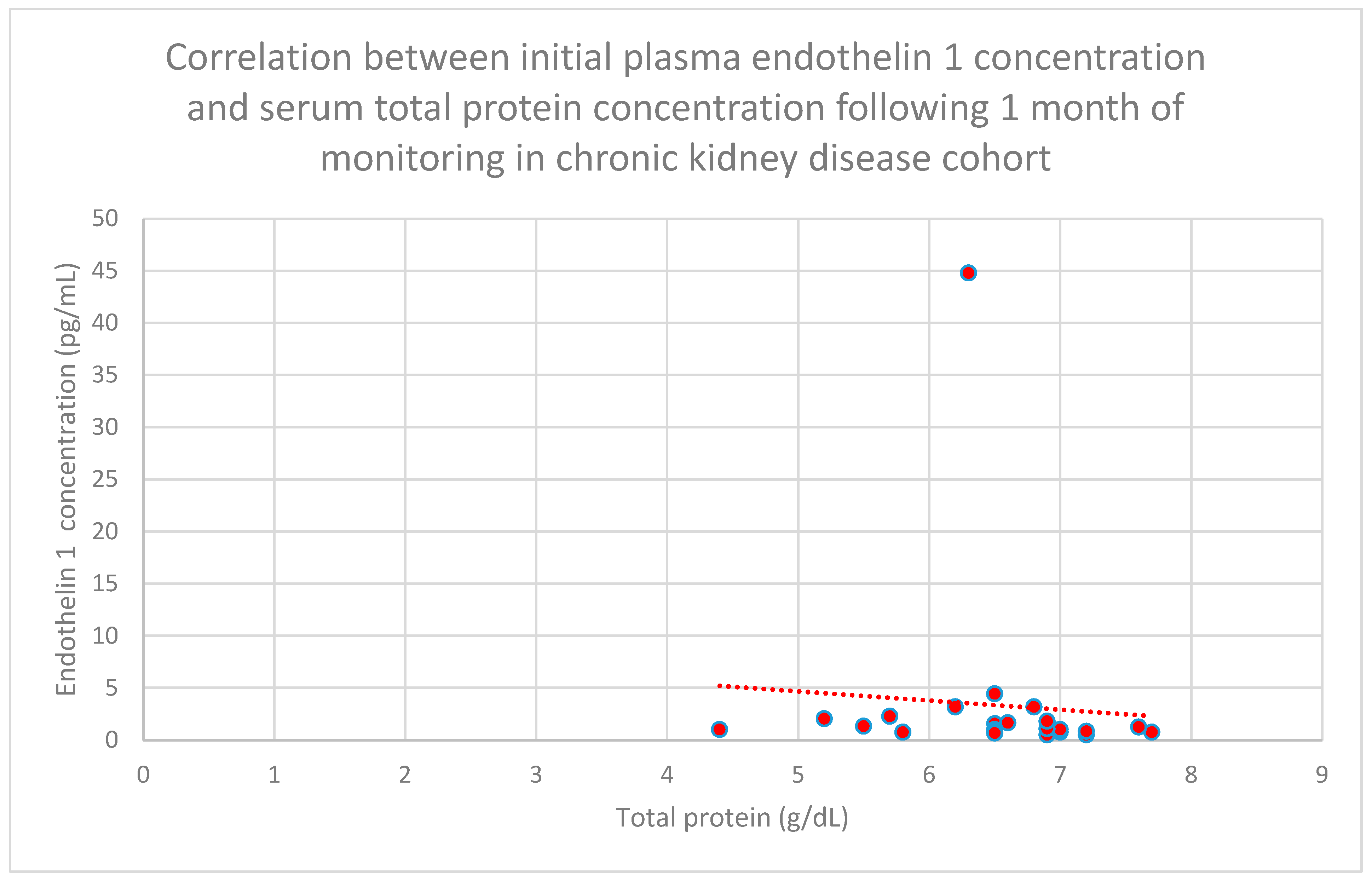

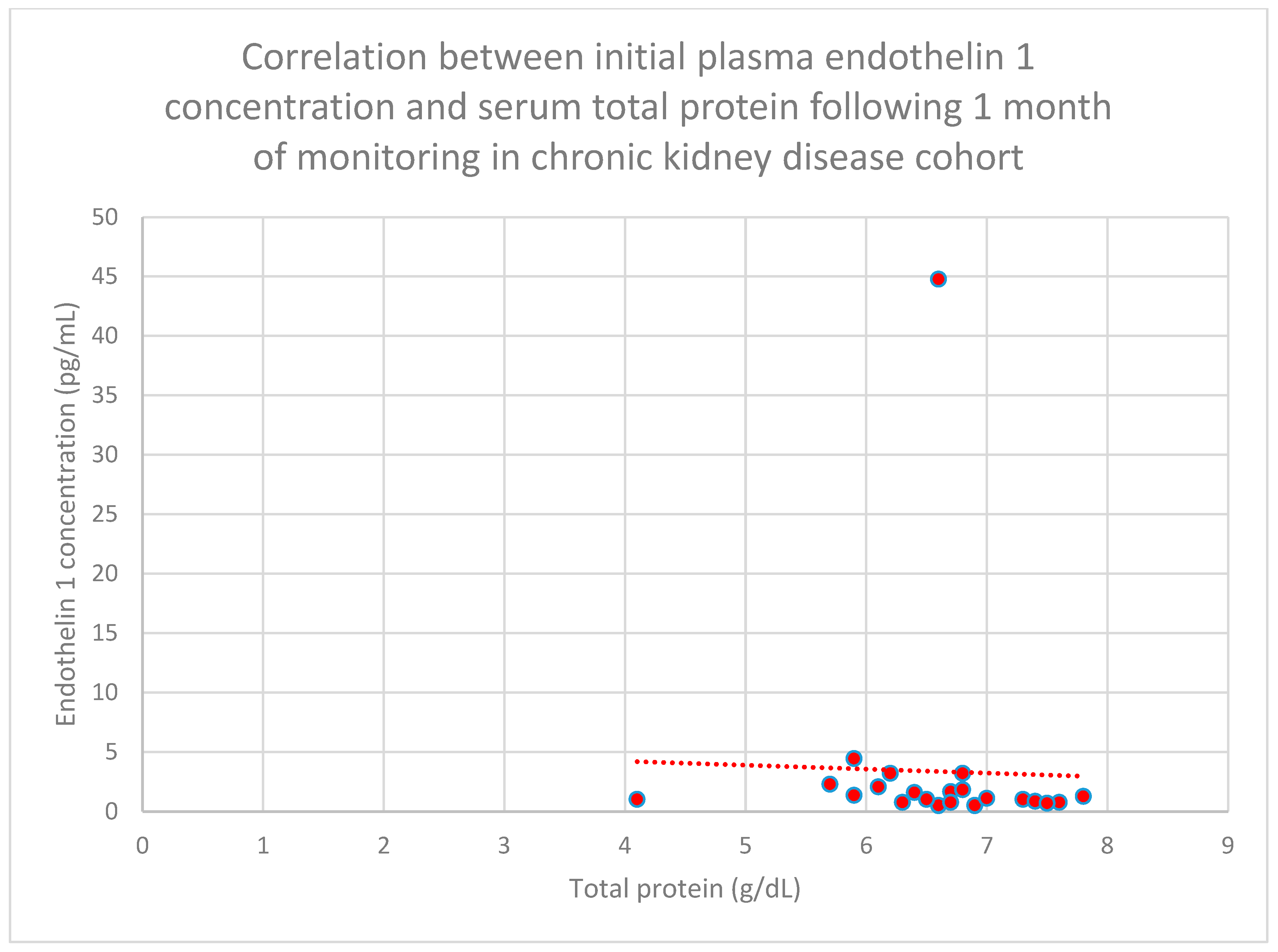

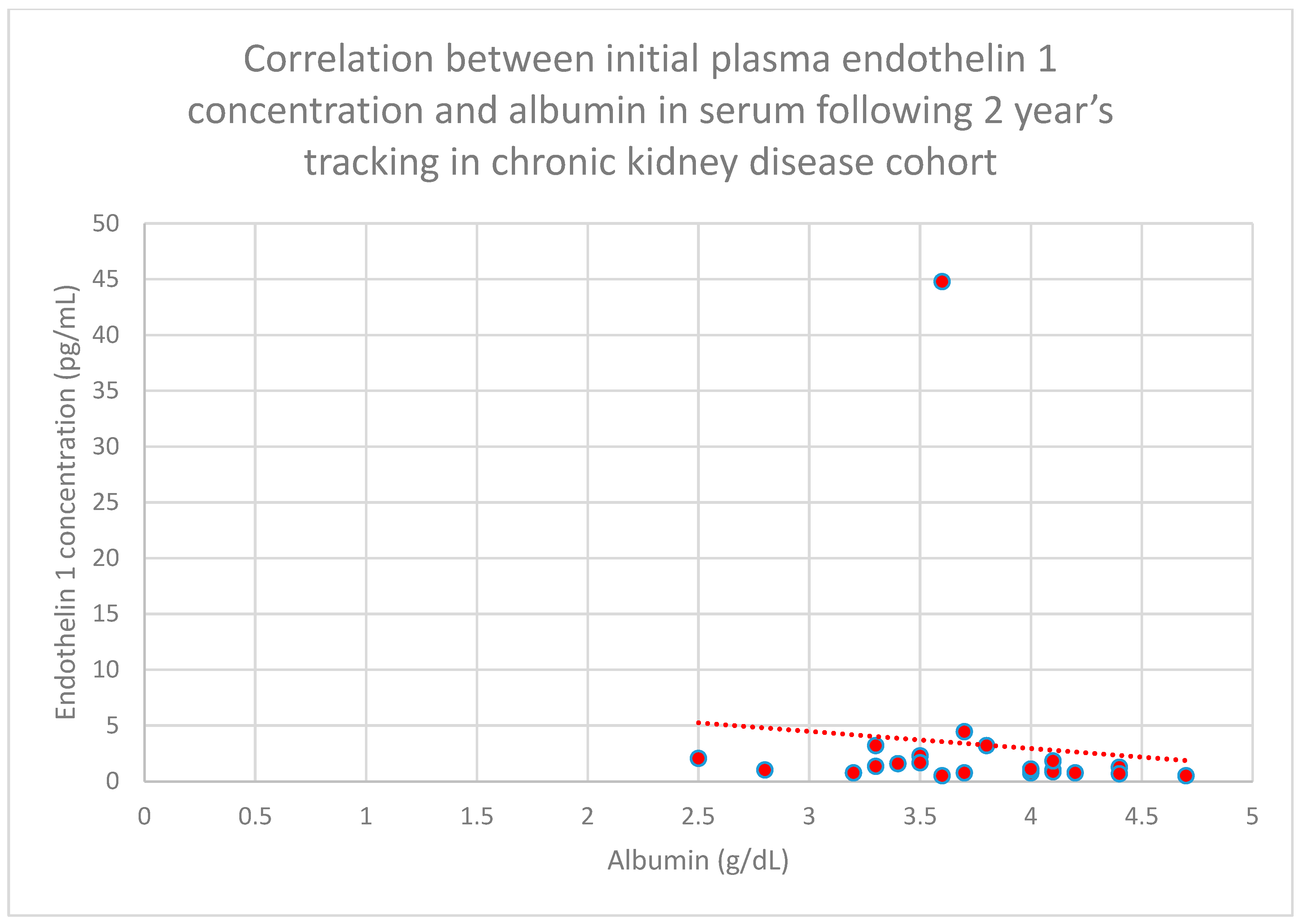

3.5. Relationship Between Patients’ Clinical Data and Endothelin 1 Levels

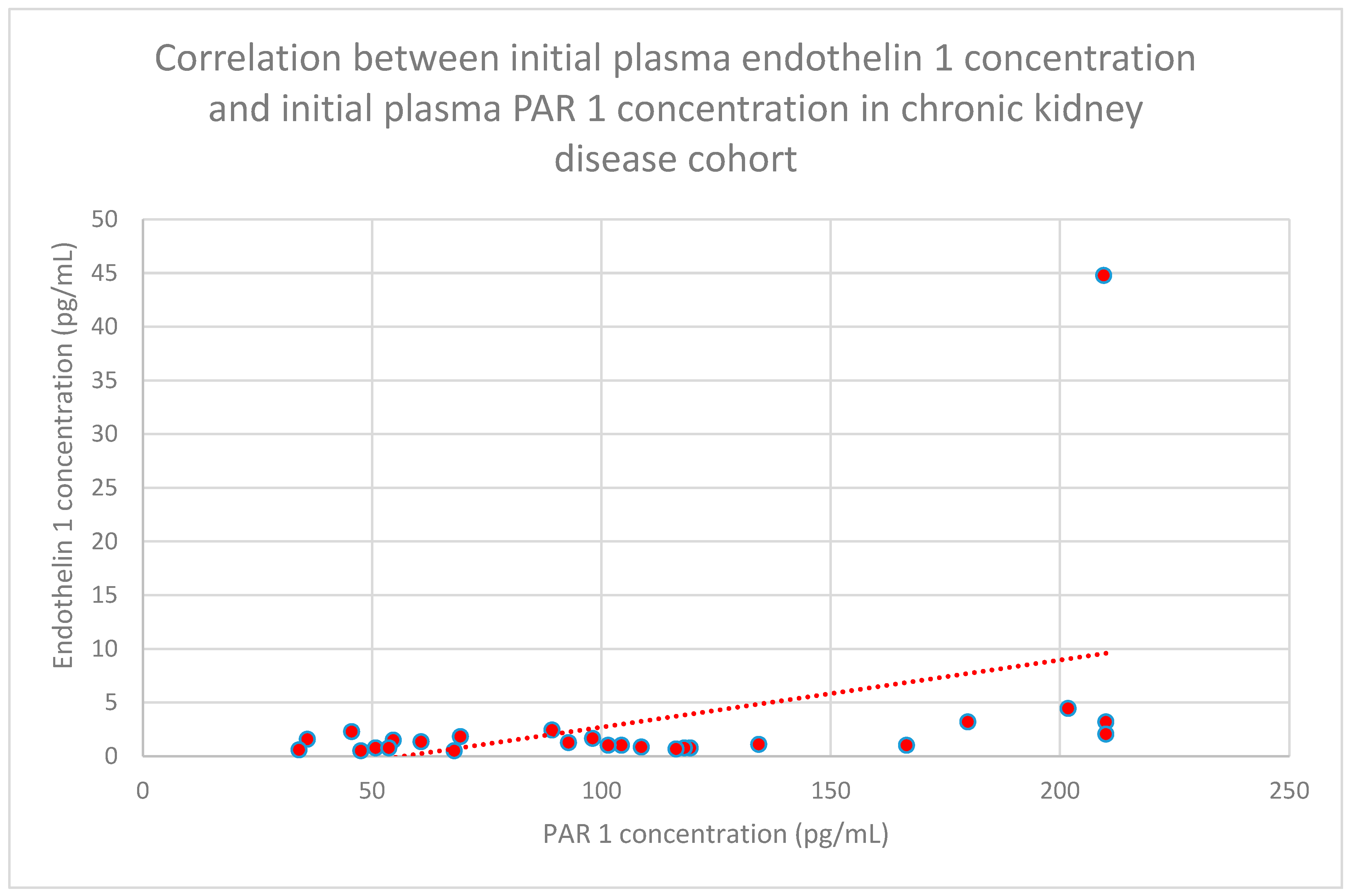

3.6. Correlations Between PAR 1 and Endothelin 1

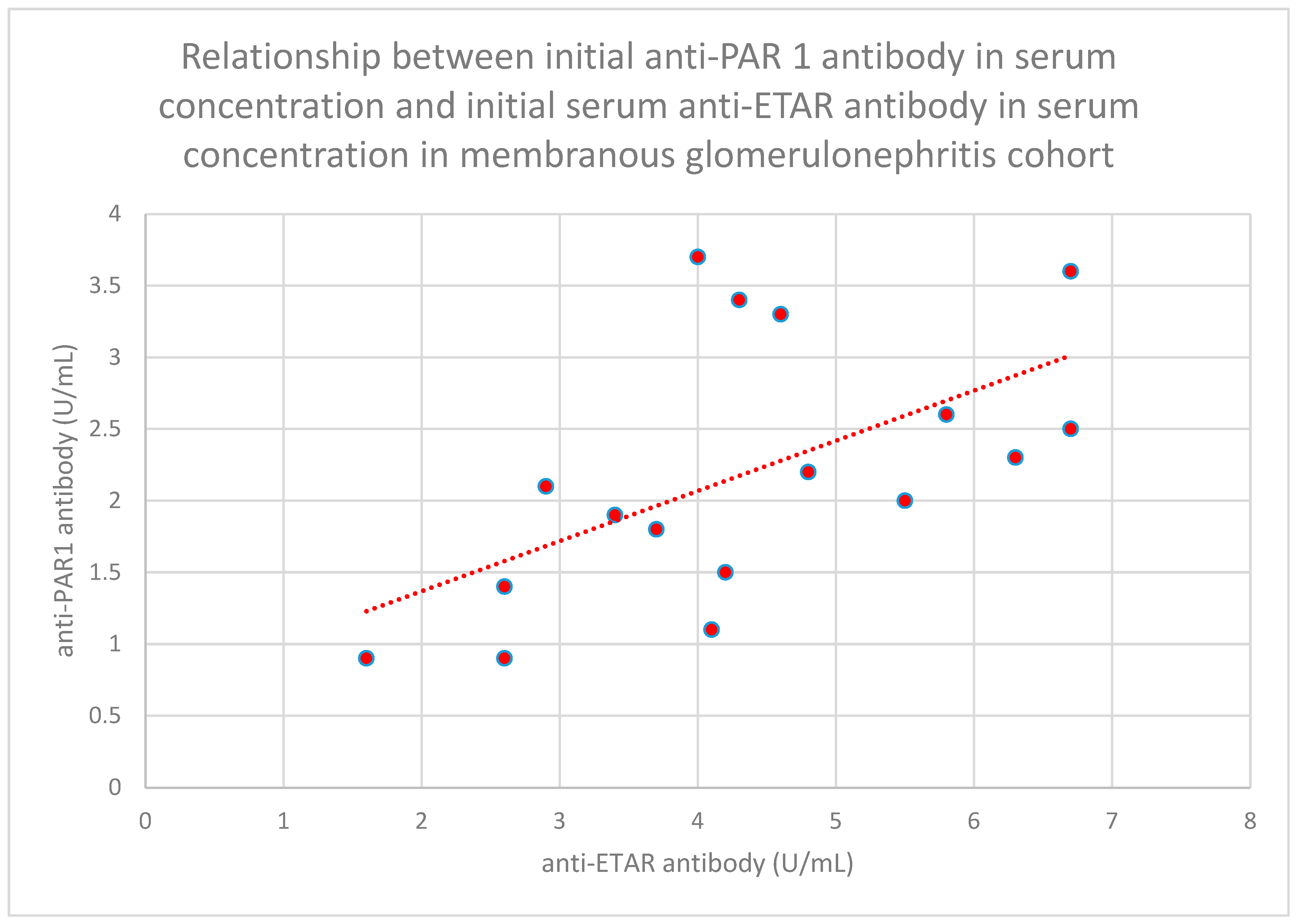

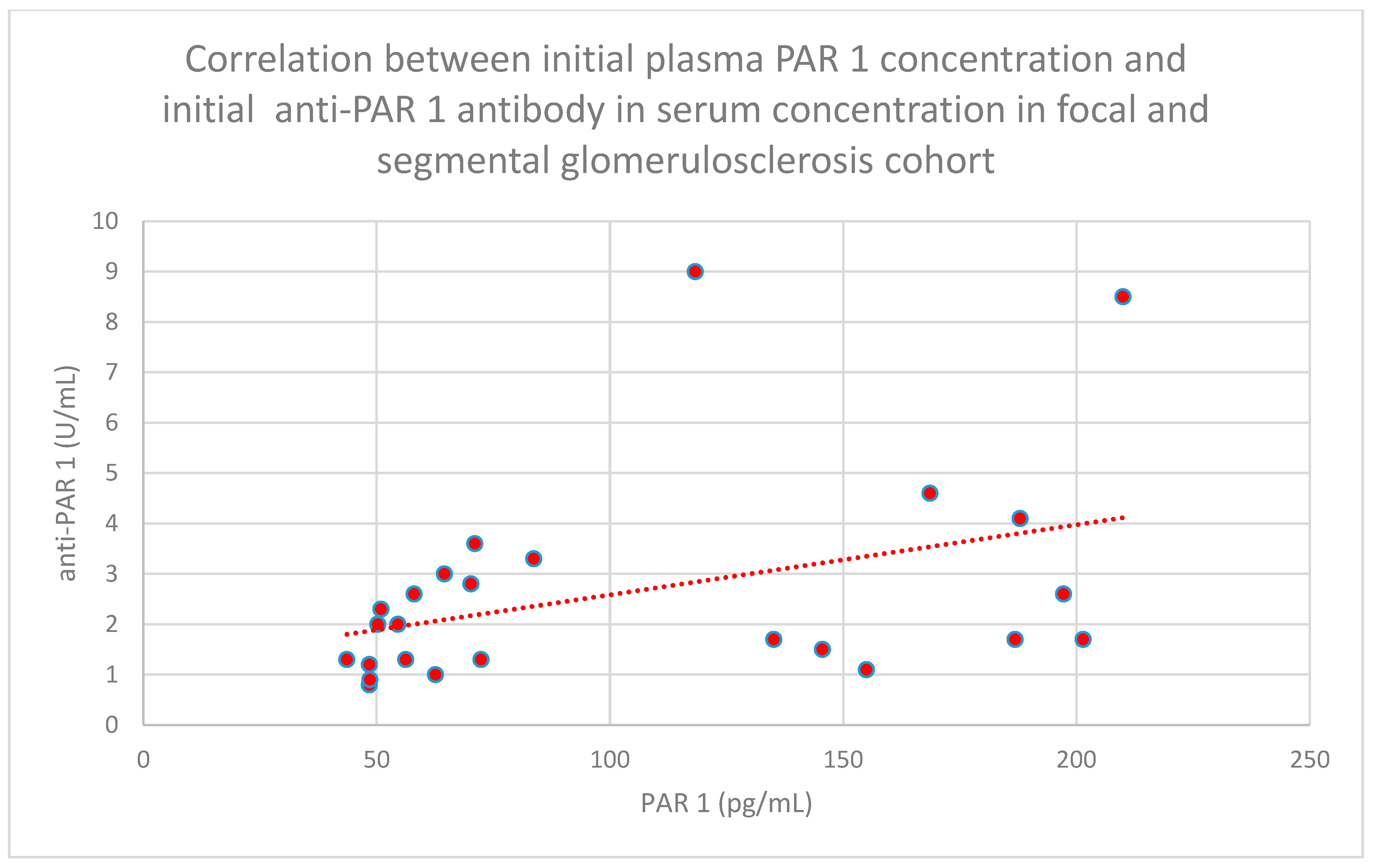

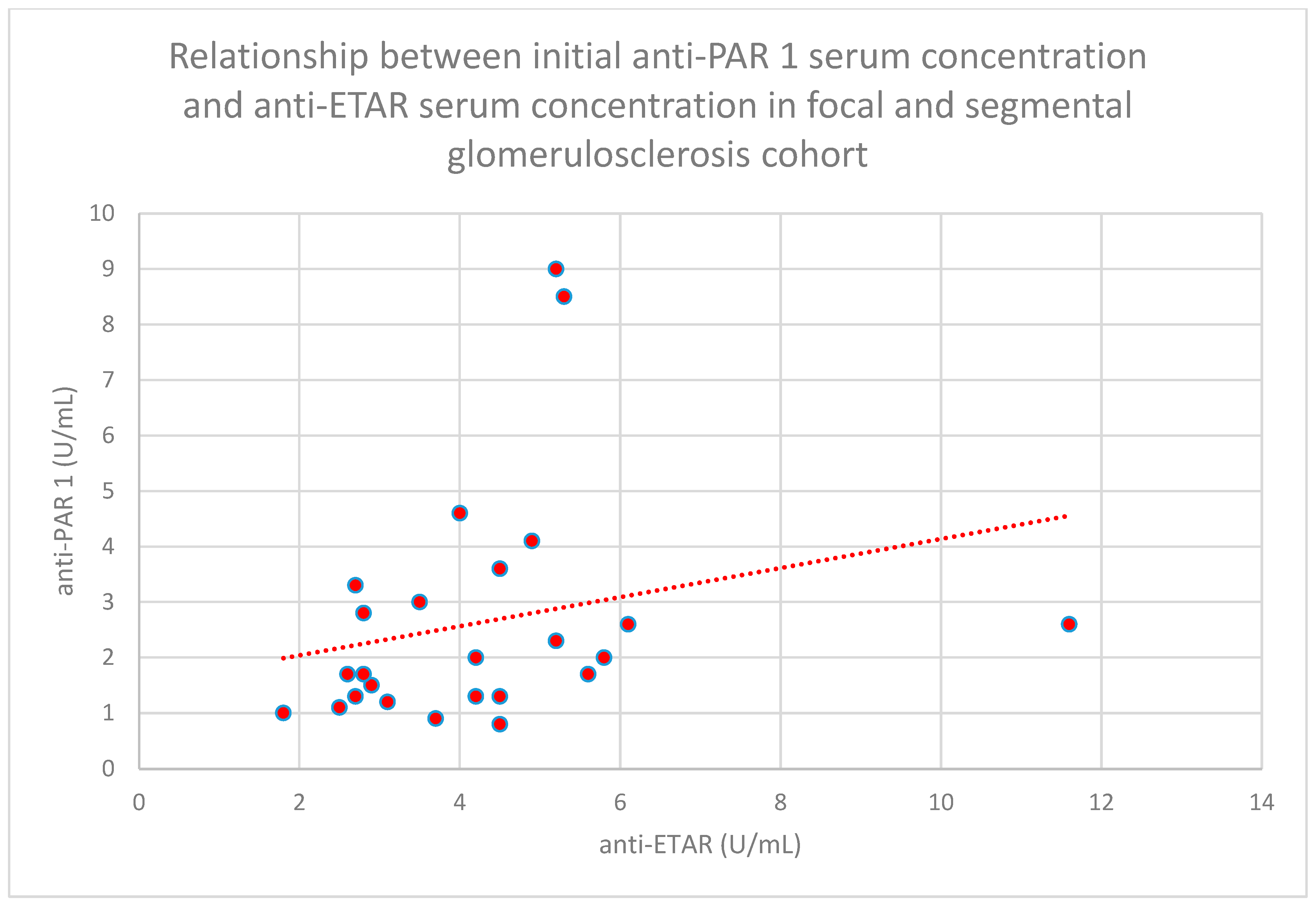

3.7. Correlations Between PAR 1 and Anti-PAR1, PAR 1 and Anti-ETAR, Endothelin1 and Anti-PAR 1, Endothelin1 and Anti-ETAR, and Anti-PAR 1 and Anti-ETAR

- -

- The relationship between initial serum anti-PAR 1 antibody concentrations and initial serum anti-ETAR antibody concentrations in the membranous nephropathy cohort (n = 17; p = 0.004; r = 0.64) (Figure 30);

- -

- The relationship between initial plasma PAR 1 concentrations and initial serum anti-PAR 1 antibody concentrations in the focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis cohort (n = 25; p = 0.01; r = 0.48) (Figure 31);

- -

- The relationship between initial serum anti-PAR 1 antibody concentrations and initial serum anti-ETAR antibody concentrations in the focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis cohort (n = 25; p = 0.04; r = 0.39) (Figure 32);

- -

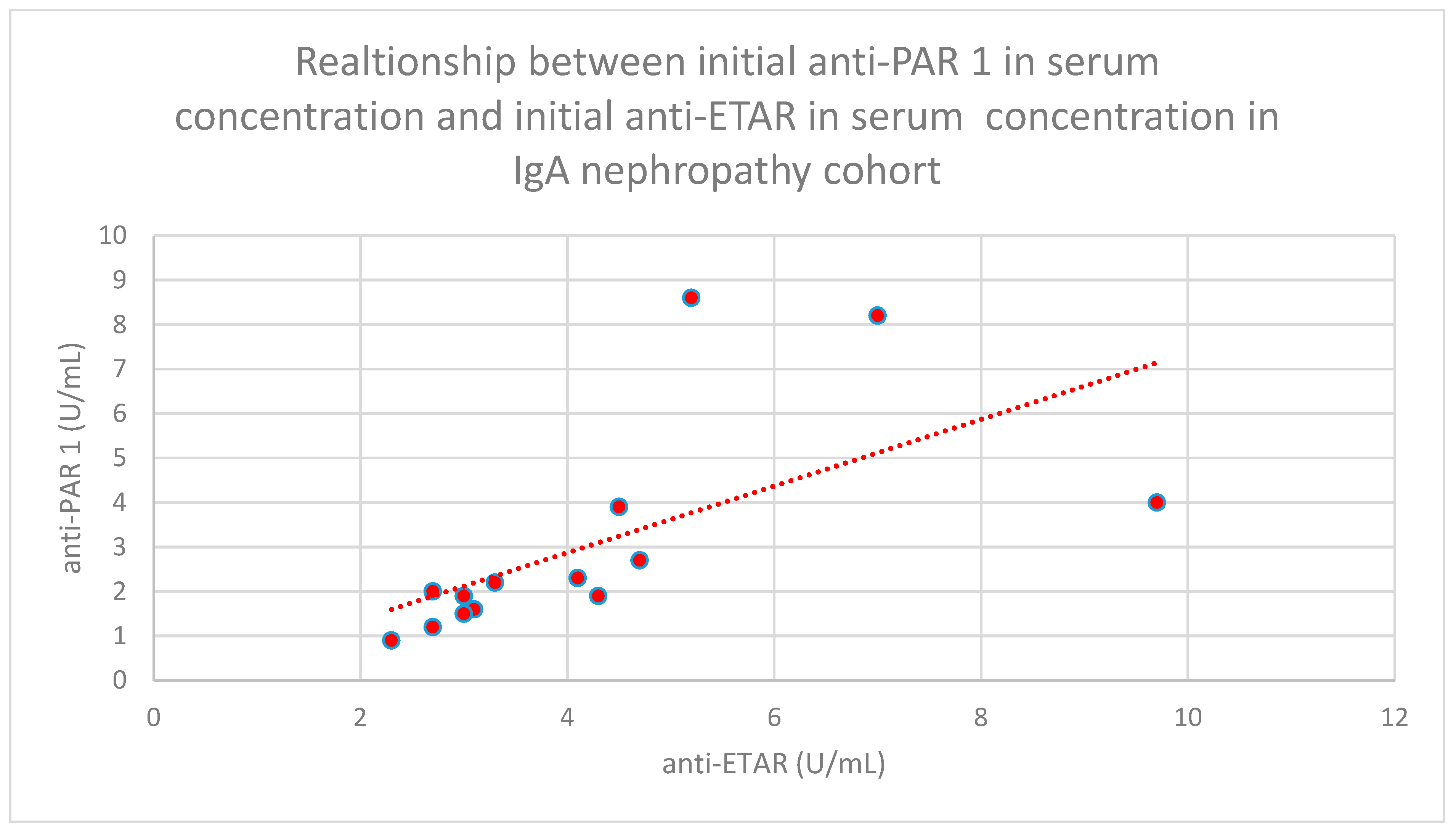

- The relationship between initial serum anti-PAR 1 antibody concentrations and initial serum anti-ETAR antibody concentrations in the IgA nephropathy cohort (n = 14; p < 0.001; r = 0.88) (Figure 33).

4. Discussion

4.1. PAR 1 Levels

4.2. Endothelin 1 Levels

4.3. Correlations Between PAR 1 and Endothelin 1

4.4. PAR 1, Endothelin 1, Anti-ETAR, and Anti-PAR 1 Antibody Correlations

4.5. Study Limitations

4.6. Study Strengths

4.7. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANAs | antinuclear antibodies |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| BUN | blood urea nitrogen |

| CKD | chronic kidney disease |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| dsDNA | anti-double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid antibodies |

| eGFR | estimated glomerular filtration |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ETAR | endothelin A receptor |

| ETBR | endothelin B receptor |

| FSGS | focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis |

| Hb | hemoglobin |

| Hct | hematocrit |

| IgA | immunoglobulin A |

| IL | interleukin |

| IU | international unit |

| NF | nuclear factor |

| PAR 1 | protease activated receptor |

| SLE | systemic lupus erythematosus |

| TGF | transforming growth factor |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

| U | unit |

References

- Heuberger, D.M.; Schuepbach, R.A. Protease-activated receptors (PARs): Mechanisms of action and potential therapeutic modulators in PAR-driven inflammatory diseases. Thromb. J. 2019, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, I.; Giri, H.; Panicker, S.R.; Rezaie, A.R. Thrombomodulin Switches Signaling and Protease-Activated Receptor 1 Cleavage Specificity of Thrombin. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedoriuk, M.; Stefanenko, M.; Bohovyk, R.; Semenikhina, M.; Lipschutz, J.H.; Staruschenko, A.; Palygin, O. Serine proteases and protease-activated receptors signaling in the kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2025, 329, C107–C117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallwitz, M.; Enoksson, M.; Thorpe, M.; Hellman, L. The extended cleavage specificity of human thrombin. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tull, S.P.; Bevins, A.; Kuravi, S.J.; Satchell, S.C.; Al-Ani, B.; Young, S.P.; Harper, L.; Williams, J.M.; Rainger, G.E.; Savage, C.O.S. PR3 and Elastase Alter PAR1 Signaling and Trigger vWF Release via a Calcium-Independent Mechanism from Glomerular Endothelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuliopulos, A.; Covic, L.; Seeley, S.K.; Sheridan, P.J.; Helin, J.; Costello, C.E. Plasmin desensitization of the PAR1 thrombin receptor: Kinetics, sites of truncation, and implications for thrombolytic therapy. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 4572–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oikonomopoulou, K.; Hansen, K.K.; Saifeddine, M.; Tea, I.; Blaber, M.; Blaber, S.I.; Scarisbrick, I.; Andrade-Gordon, P.; Cottrell, G.S.; Bunnett, N.W.; et al. Proteinase activated receptors, targets for kallikrein signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 32095–32112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagang, N.; Gupta, K.; Singh, G.; Kanuri, S.H.; Mehan, S. Protease-activated receptors in kidney diseases: A comprehensive review of pathological roles, therapeutic outcomes and challenges. Rev. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2023, 377, 110470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-González, J.F.; Mora-Fernández, C.; Muros de Fuentes, M.; García-Pérez, J. Inflammatory molecules and pathways in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2011, 7, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, M.; Kurihara, H.; Kimura, S.; Tomobe, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Mitsui, Y.; Yazaki, Y.; Goto, K.; Masaki, T. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature 1988, 332, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teder, P.; Noble, P.W. A cytokine reborn? Endothelin-1 in pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2000, 23, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banecki, K.; Dora, K.A. Endothelin-1 in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miguel, C.; Speed, J.S.; Kasztan, M.; Gohar, E.Y.; Pollock, D.M. Endothelin-1 and the kidney: New perspectives and recent findings. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2016, 25, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffrin, E.L.; Pollock, D.M. Endothelin System in Hypertension and Chronic Kidney Disease. Hypertension 2024, 81, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, M.; Moccaldi, B.; Civieri, G.; Cuberli, A.; Doria, A.; Tona, F.; Zanatta, E. Autoantibodies Targeting G-Protein-Coupled Receptors: Pathogenetic, Clinical and Therapeutic Implications in Systemic Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymczak, M.; Heidecke, H.; Żabińska, M.; Janek, Ł.; Wronowicz, J.; Kujawa, K.; Schulze-Forster, K.; Marek-Bukowiec, K.; Gołębiowski, T.; Banasik, M. The Influence of Anti-PAR 1 and Anti-ACE 2 Antibody Levels on the Course of Specific Glomerulonephritis Types. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczak, M.; Heidecke, H.; Żabińska, M.; Janek, Ł.; Wronowicz, J.; Kujawa, K.; Bukowiec-Marek, K.; Gołębiowski, T.; Skalec, K.; Schulze-Forster, K.; et al. The Influence of Anti-ETAR and Anti-CXCR3 Antibody Levels on the Course of Specific Glomerulonephritis Types. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwabara, Y.; Tanaka-Ishikawa, M.; Abe, K.; Hirano, M.; Hirooka, Y.; Tsutsui, H.; Sunagawa, K.; Hirano, K. Proteinase-activated receptor 1 antagonism ameliorates experimental pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 115, 1357–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höcherl, K.; Gerl, M.; Schweda, F. Proteinase-activated receptors 1 and 2 exert opposite effects on renal renin release. Hypertension 2011, 58, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.I.; Sjöström, D.J.; Quach, H.Q.; Hägerström, K.; Hurler, L.; Kajdácsi, E.; Cervenak, L.; Prohászka, Z.; Toonen, E.J.M.; Mohlin, C.; et al. Storage of Transfusion Platelet Concentrates Is Associated with Complement Activation and Reduced Ability of Platelets to Respond to Protease-Activated Receptor-1 and Thromboxane A2 Receptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Ithychanda, S.S.; Plow, E.F. Histone 2B Facilitates Plasminogen-Enhanced Endothelial Migration through Protease Activated Receptor 1 (PAR1) and Protease-Activated Receptor 2 (PAR2). Biomolecules 2022, 12, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dólleman, S.C.; Agten, S.M.; Spronk, H.M.H.; Hackeng, T.M.; Bos, M.H.A.; Versteeg, H.H.; van Zonneveld, A.J.; de Boer, H.C. Thrombin in complex with dabigatran can still interact with PAR-1 via exosite-I and instigate loss of vascular integrity. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 20, 996–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waasdorp, M.; Duitman, J.; Florquin, S.; Spek, C.A. Protease-activated receptor-1 deficiency protects against streptozotocin induced diabetic nephropathy in mice. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Nakano, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, W.; Nishida, M.; Kuwabara, T.; Morishita, A.; Hitomi, H.; Mori, K.; et al. A protease-activated receptor-1 antagonist protects against podocyte injury in a mouse model of nephropathy. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 135, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.S.; Kim, I.S.; Rezaie, A.R. Thrombin down-regulates the TGF-beta-mediated synthesis of collagen and fibronectin by human proximal tubule epithelial cells through the EPCR-dependent activation of PAR-1. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010, 225, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palygin, O.; Ilatovskaya, D.V.; Staruschenko, A. Protease-activated receptors in kidney disease progression. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2016, 311, F1140–F1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, C.J.; Chesor, M.; Hunter, S.E.; Hayes, B.; Barr, R.; Roberts, T.; Barrington, F.A.; Farmer, L.; Ni, L.; Jackson, M.; et al. Podocyte protease activated receptor 1 stimulation in mice produces focal segmental glomerulosclerosis mirroring human disease signaling events. Kidney Int. 2023, 104, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medipally, A.; Xiao, M.; Biederman, L.; Satoskar, A.A.; Ivanov, I.; Rovin, B.; Parikh, S.; Kerlin, B.A.; Brodsky, S.V. Role of protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) in the glomerular filtration barrier integrity. Physiol. Rep. 2022, 10, e15343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Waller, A.P.; Agrawal, S.; Wolfgang, K.J.; Luu, H.; Shahzad, K.; Isermann, B.; Smoyer, W.E.; Nieman, M.T.; Kerlin, B.A. Thrombin-Induced Podocyte Injury Is Protease-Activated Receptor Dependent. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 2618–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanenko, M.; Fedoriuk, M.; Mamenko, M.; Semenikhina, M.; Nowling, T.K.; Lipschutz, J.H.; Maximyuk, O.; Staruschenko, A.; Palygin, O. PAR1-mediated Non-periodical Synchronized Calcium Oscillations in Human Mesangial Cells. Function 2024, 5, zqae030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Tang, S.; Yan, J.; Li, H.; Wan, Z.; Wang, L.; Yan, X. Activation of Protease-Activated Receptor-1 Causes Chronic Pain in Lupus-Prone Mice Via Suppressing Spinal Glial Glutamate Transporter Function and Enhancing Glutamatergic Synaptic Activity. J. Pain 2023, 24, 1163–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, G.; Luecht, C.; Gyamfi, M.A.; da Fonseca, D.L.M.; Wang, P.; Zhao, H.; Gong, Z.; Chen, L.; Ashraf, M.I.; Heidecke, H.; et al. Autoantibodies from patients with kidney allograft vasculopathy stimulate a proinflammatory switch in endothelial cells and monocytes mediated via GPCR-directed PAR1-TNF-alpha signaling. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1289744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virdis, A.; Schiffrin, E.L. Vascular inflammation: A role in vascular disease in hypertension? Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2003, 12, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeager, M.E.; Belchenko, D.D.; Nguyen, C.M.; Colvin, K.L.; Ivy, D.D.; Stenmark, K.R. Endothelin-1, the unfolded protein response, and persistent inflammation: Role of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 46, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guruli, G.; Pflug, B.R.; Pecher, S.; Makarenkova, V.; Shurin, M.R.; Nelson, J.B. Function and survival of dendritic cells depend on endothelin-1 and endothelin receptor autocrine loops. Blood 2004, 104, 2107–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaun, N.; Goddard, J.; Kohan, D.E.; Pollock, D.M.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Webb, D.J. Role of Endothelin-1 in Clinical Hypertension. Hypertension 2008, 52, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunter, U.; Seikrit, C.; Floege, J. Novel agents for treating IgA nephropathy. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2023, 32, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tycová, I.; Hrubá, P.; Maixnerová, D.; Girmanová, E.; Mrázová, P.; Straňavová, L.; Zachoval, R.; Merta, M.; Slatinská, J.; Kollár, M.; et al. Molecular profiling in IgA nephropathy and focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. Physiol. Res. 2018, 67, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Lest, N.A.; Bakker, A.E.; Dijkstra, K.L.; Zandbergen, M.; Heemskerk, S.A.C.; Wolterbeek, R.; Bruijn, J.A.; Scharpfenecker, M. Endothelial Endothelin Receptor A Expression Is Associated With Podocyte Injury and Oxidative Stress in Patients With Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 1939–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeijer, J.D.; Kohan, D.E.; Webb, D.J.; Dhaun, N.; Heerspink, H.J.L. Endothelin receptor antagonists for the treatment of diabetic and nondiabetic chronic kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2021, 30, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zager, R.A.; Johnson, A.C.; Andress, D.; Becker, K. Progressive endothelin-1 gene activation initiates chronic/end-stage renal disease following experimental ischemic/reperfusion injury. Kidney Int. 2013, 84, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, K.D.; Komers, R.; Osman, S.A.; Oyama, T.T.; Lindsley, J.N.; Anderson, S. Gender hormones and the progression of experimental polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005, 68, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasztan, M.; Fox, B.M.; Speed, J.S.; De Miguel, C.; Gohar, E.Y.; Townes, T.M.; Kutlar, A.; Pollock, J.S.; Pollock, D.M. Long-Term Endothelin-A Receptor Antagonism Provides Robust Renal Protection in Humanized Sickle Cell Disease Mice. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 2443–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinazzi, E.; Puccetti, A.; Giuseppe, P.; Alessandro, B.; Giuseppe, A.; Confente, F.; Dolcino, M.; Ruggero, B.; Giacomo, M.; Ottria, A.; et al. Endothelin Receptors Expressed by Immune Cells Are Involved in Modulation of Inflammation and in Fibrosis: Relevance to the Pathogenesis of Systemic Sclerosis. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 147616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattinger, K.; Funk, C.; Pantze, M.; Weber, C.; Reichen, J.; Stieger, B.; Meieret, P.J. The endothelin antagonist bosentan inhibits the canalicular bile salt export pump: A potential mechanism for hepatic adverse reactions. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 69, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Kiyosue, A.; Wheeler, D.C.; Lin, M.; Wijkmark, E.; Carlson, G.; Mercier, A.K.; Åstrand, M.; Ueckert, S.; Greasley, P.J.; et al. Zibotentan in combination with dapagliflozin compared with dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease (ZENITH-CKD): A multicentre, randomised, active-controlled, phase 2b, clinical trial. Lancet 2023, 402, 2004–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simes, B.C.; MacGregor, G.G. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors: A Clinician’s Guide. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2019, 12, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.N.; Gesualdo, L.; Murphy, E.; Rheault, M.N.; Srivastava, T.; Tesar, V.; Komers, R.; Trachtman, H. Sparsentan for Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis in the DUET Open-Label Extension: Long-term Efficacy and Safety. Kidney Med. 2024, 6, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Radhakrishnan, J.; Alpers, C.E.; Barratt, J.; Bieler, S.; Diva, U.; Inrig, J.; Komers, R.; Mercer, A.; Noronha, I.L.; et al. Protect Investigators Sparsentan in patients with IgA nephropathy: A prespecified interim analysis from a randomised, double-blind, active-controlled clinical trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 1584–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Jardine, M.; Kohan, D.E.; Lafayette, R.A.; Levin, A.; Liew, A.; Zhang, H.; Noronha, I.; Trimarchi, H.; Hou, F.F.; et al. Study Design and Baseline Characteristics of ALIGN, a Randomized Controlled Study of Atrasentan in Patients With IgA Nephropathy. Kidney Int. Rep. 2024, 10, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tas, F.; Bilgin, E.; Karabulut, S.; Erturk, K.; Duranyildiz, D. Clinical significance of serum Protease-Activated Receptor-1 (PAR-1) levels in patients with cutaneous melanoma. BBA Clin. 2016, 5, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lech, M.; Anders, H.J.J. The pathogenesis of lupus nephritis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, E.D.; Wu, D.; Meydani, S.N. Age-associated alterations in immune function and inflammation. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 118, 110576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navis, G.; Faber, H.J.; de Zeeuw, D.; de Jong, P.E. ACE inhibitors and the kidney. A risk-benefit assessment. Drug Saf. 1996, 15, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.; Sorokin, A. Endothelin and the glomerulus in chronic kidney disease. Semin. Nephrol. 2015, 35, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specific Kidney Disease | Initial Level of Creatinine in Serum (mg/dL) | Initial Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (mL/min./ 1.73 m2) MDRD | BUN (mg/dL) | Albumin/Creatinine Ratio | Amount of Protein in Urine (g/per Day) | Initial Total Protein Level in Serum (g/dL) | Initial Albumin Level in Serum (g/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| membranous glomerulonephritis (n = 19) | 1.17 (0.61–3.3) | 70 (15–116) | 11 (8–32) | 1.52 (0.06–7.34) | 2.64 (1.13–5.71) | 4.9 (4.35–5.6) | 2.8 (2.5–3.2) |

| focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (n = 30) | 1.22 (0.73–3.19) | 62 (31–126) | 11 (5–30) | 1.08 (0.3–7.5) | 2.14 (0.04–7.46) | 5.35 (4.4–6.1) | 3.2 (2.5–3.6) |

| systemic lupus erythematosus (n = 22) | 1.10 (0.74–2.19) | 60 (24–116) | 9 (4–23) | 0.71 (0.02–3.13) | 1.26 (0.27–2.24) | 5.7 (5.2–6.4) | 3.3 (3–3.9) |

| IgA nephropathy (n = 16) | 0.92 (0.59–1.55) | 68 (35–131) | 9.5 (6–20) | 0.6 (0.05–2.2) | 1.06 (0.64–2) | 5.65 (4.9–6.3) | 3.4 (2.75–4) |

| mesangial proliferative (non-IgA) glomerulonephritis (n = 7) | 0.91 (0.59–1.55) | 90 (40–131) | 9 (6–16) | 0.82 (0.17–3.4) | 1.46 (1.14–4.88) | 5.0 (4.5–5.2) | 2.8 (2.3–3.2) |

| control group (n = 22) | 0.94 (0.68–1.19) | 70 (64.3–101.6) | 9 (7–11) | 0(0–0) | 0(0–0) | 7.3 (6.5–8.3) | 4.5 (4.2–5.2) |

| chronic kidney disease (n = 27) | 2.69 (1.23–10.51) | 23 (5–52) | 25.5 (11–97) | 0.42 (0.04–12.2) | 0.82 (0.08–23.8) | 6.7 (3.4–7.7) | 3.8 (2–4.6) |

| hemodialysis (n = 26) | 5.2 (3.2–8.4) | 11 (6–18) | Not applicable | Not applicable | 6.4 (4.5–7.6) | 3.65 (2.8–4.3) |

| Specific Kidney Disease | Age (Years) | Sex (Percent of Males) | Hb (g/dL) | Hct (%) | Leukocytes (Number/Microliter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| membranous glomerulonephritis (n = 19) | 50.5 (39–60.5) | 80% | 13.4 (11.5–16) | 45 (37.2–52.6) | 6.8 (2.5–10.8) |

| focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (n = 30) | 47 (31–59) | 67% | 13.6 (9.3–16.8) | 44.6 (30.6–55) | 7.9 (4.1–11) |

| lupus nephritis (n = 22) | 34.5 (31–47) | 27% | 13 (10.5–17.3) | 42.6 (34.5–59) | 6.3 (2.9–10.9) |

| IgA nephropathy (n = 16) | 45.5 (31–59) | 50% | 14.6 (12.2–16.4) | 48.1 (40.1–54) | 8.4 (4.4–10.9) |

| Mesangial proliferative (non-IgA) glomerulonephritis (n = 7) | 22 (20–52) | 28% | 14.5 (10.1–18) | 47.5 (33.2–55) | 8.1 (6–10.5) |

| control group (n = 22) | 47.5 (30–59) | 54% | 14.5 (9.4–17.9) | 43.4 (37–50) | 6.3 (3.5–8.3) |

| chronic kidney disease (n = 27) | 47 (19–64) | 59% | 12.9 (8.2–18.1) | 38.8 (25–51.4) | 8.1 (4.4–11) |

| hemodialysis (n = 26) | 47.5 (36–62) | 54% | 10 (7.4–12.8) | 30.2 (23–41) | 6.9 (4.4–11) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Szymczak, M.; Żabińska, M.; Kościelska-Kasprzak, K.; Bartoszek, D.; Heidecke, H.; Schulze-Forster, K.; Janek, Ł.; Kujawa, K.; Wronowicz, J.; Marek-Bukowiec, K.; et al. The Influence of PAR 1 and Endothelin 1 on the Course of Specific Kidney Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010221

Szymczak M, Żabińska M, Kościelska-Kasprzak K, Bartoszek D, Heidecke H, Schulze-Forster K, Janek Ł, Kujawa K, Wronowicz J, Marek-Bukowiec K, et al. The Influence of PAR 1 and Endothelin 1 on the Course of Specific Kidney Diseases. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):221. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010221

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzymczak, Maciej, Marcelina Żabińska, Katarzyna Kościelska-Kasprzak, Dorota Bartoszek, Harald Heidecke, Kai Schulze-Forster, Łucja Janek, Krzysztof Kujawa, Jakub Wronowicz, Karolina Marek-Bukowiec, and et al. 2026. "The Influence of PAR 1 and Endothelin 1 on the Course of Specific Kidney Diseases" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010221

APA StyleSzymczak, M., Żabińska, M., Kościelska-Kasprzak, K., Bartoszek, D., Heidecke, H., Schulze-Forster, K., Janek, Ł., Kujawa, K., Wronowicz, J., Marek-Bukowiec, K., Gołębiowski, T., & Banasik, M. (2026). The Influence of PAR 1 and Endothelin 1 on the Course of Specific Kidney Diseases. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010221