Comparative Analysis of Implant Placement Accuracy Using Augmented Reality Technology Versus 3D-Printed Surgical Guides: A Controlled In Vitro Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

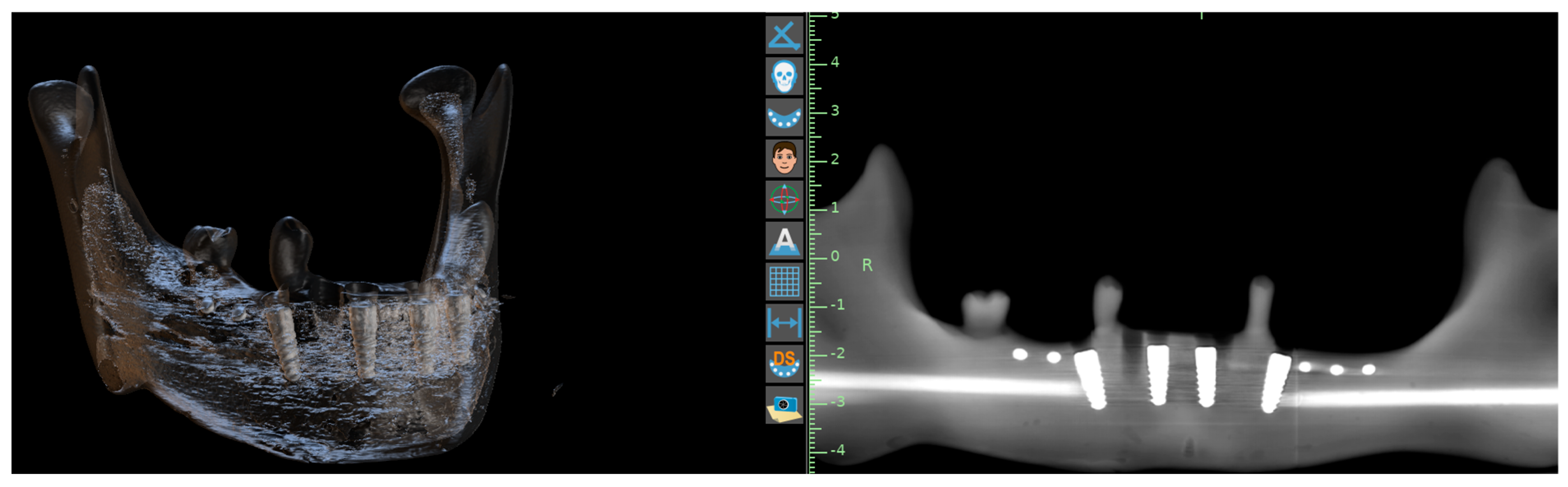

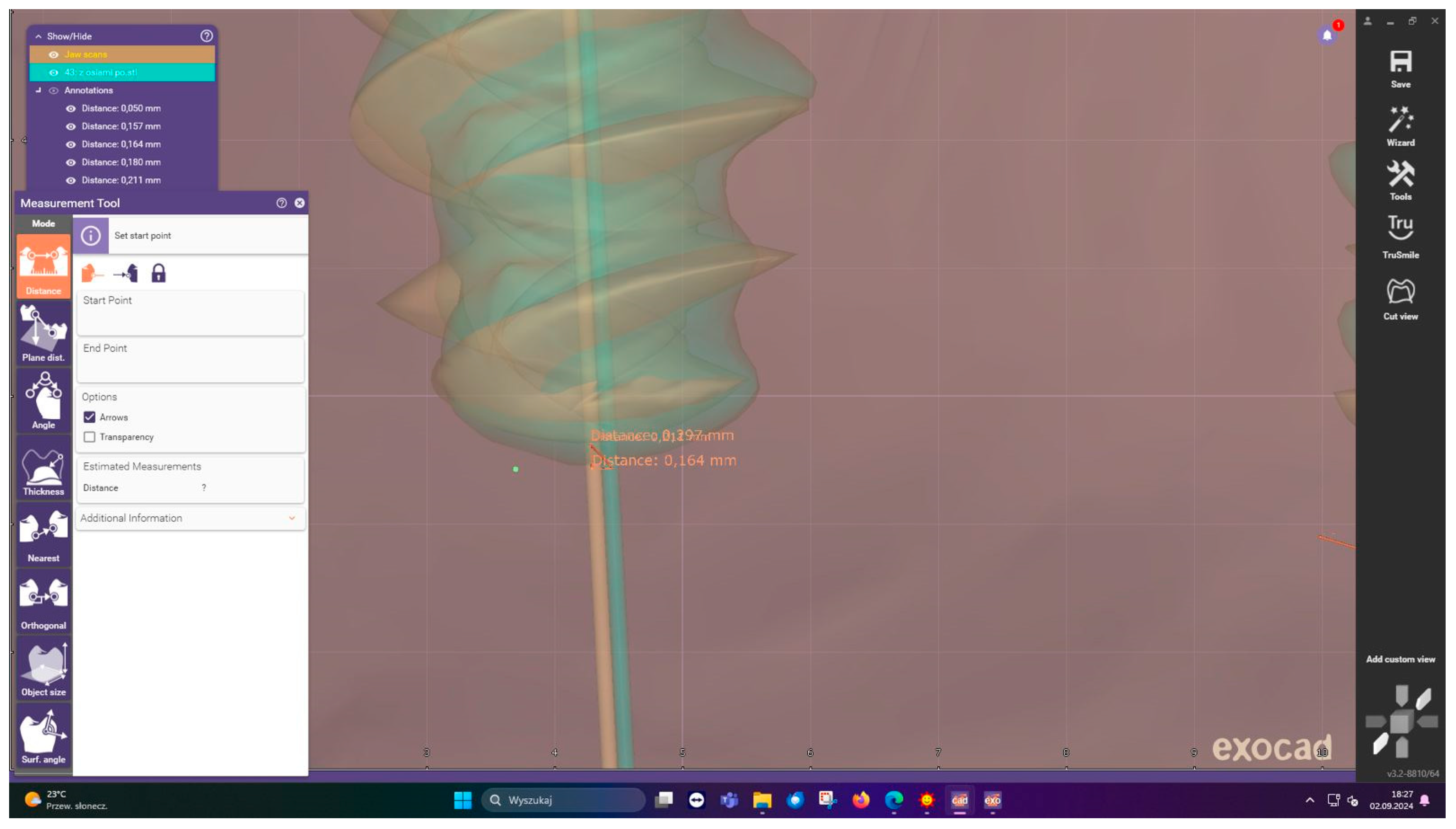

2. Material and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, L.W.; Zhao, X.E.; Yan, Q.; Xia, H.B.; Sun, Q. Dynamic navigation system-guided trans-inferior alveolar nerve implant placement in the atrophic posterior mandible: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 3907–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.M.; Zhu, Y.; Wei, J.X.; Zhang, C.N.; Shi, J.Y.; Lai, H.C. Accuracy of dynamic navigation in implant surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2021, 32, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.G.; Lee, W.J.; Lee, S.S.; Heo, M.S.; Huh, K.H.; Choi, S.C.; Kim, T.I.; Yi, W.J. An advanced navigational surgery system for dental implants completed in a single visit: An in vitro study. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstein, G.; Tarnow, D. The mental foramen and nerve: Clinical and anatomical factors related to dental implant placement: A literature review. J. Periodontol. 2006, 77, 1933–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spille, J.; Helmstetter, E.; Kübel, P.; Weitkamp, J.-T.; Wagner, J.; Wieker, H.; Naujokat, H.; Flörke, C.; Wiltfang, J.; Gülses, A. Learning Curve and Comparison of Dynamic Implant Placement Accuracy Using a Navigation System in Young Professionals. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. Accuracy of Mucosa Supported Guided Dental Implant Surgery. Clin. Case Rep. 2018, 6, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnusamy, S.; Gonzalez, J.; Holtzclaw, D. A Systematic Approach to Restoring Full Arch Length with Maxillary Fixed Implant Reconstruction: The PATZi Protocol. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2023, 38, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqutaibi, A.Y.; Alghauli, M.A.; Aboalrejal, A.; Mulla, A.K.; Almohammadi, A.A.; Aljayyar, A.W.; Alharbi, E.S.; Alsaeedi, A.K.; Arabi, L.F.; Alhajj, N.A.; et al. Quantitative and qualitative 3D analysis of mandibular lingual concavities: Implications for dental implant planning in the posterior mandible. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2024, 10, e12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargallo-Albiol, J.; Barootchi, S.; Salomó-Coll, O.; Wang, H.L. Advantages and disadvantages of implant navigation surgery: A systematic review. Ann. Anat. 2019, 225, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, R.; Manacorda, M.; Abundo, R.; Lucchina, A.G.; Scarano, A.; Crocetta, C.; Muzio, L.L.; Gherlone, E.F.; Mastrangelo, F. Accuracy of edentulous computer-aided implant surgery as compared to virtual planning: A retrospective multicenter study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekertzi, C.; Koukouviti, M.M.; Chatzigianni, A.; Kolokitha, O.E. Dynamic implant surgery—An accurate alternative to stereolithographic guides—Systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangano, F.G.; Admakin, O.; Lerner, H.; Mangano, C. Artificial intelligence and augmented reality for guided implant surgery planning: A proof of concept. J. Dent. 2023, 133, 104485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, A.; Pulijala, Y. The application of virtual reality and augmented reality in Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 238. [Google Scholar]

- Vercruyssen, M.; Cox, C.; Naert, I.; Jacobs, R.; Teughels, W.; Quirynen, M. Accuracy and patient-centered outcome variables in guided implant surgery: A RCT comparing immediate with delayed loading. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2014, 27, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.; Fehlhofer, J.; Kesting, M.R.; Matta, R.E.; Buchbender, M. Introducing a novel educational training programme in dental implantology for pregraduate dental students. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2024, 28, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, G.; Vignudelli, E.; Barausse, C.; Bonifazi, L.; Renzi, T.; Tayeb, S.; Felice, P. Accuracy of semi-occlusive CAD/CAM titanium mesh using the reverse guided bone regeneration digital protocol: A preliminary clinical study. Int. J. Oral Implantol. 2024, 17, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, F.; Pereira, P.; Falcão-Costa, C.; Falcão, A.; Fernandes, J.C.H.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Rios, J.V. Comparison of the accuracy/precision among guided (static), manual, and dynamic navigation in dental implant surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 29, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, H.; Ma, F.; Weng, J.; Du, Y.; Wu, B.; Sun, F. Accuracy of Dynamic Navigation System for Immediate Dental Implant Placement. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2025, 57, 85–90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ma, F.; Wei, T.; Du, Y.; Wu, B.; Sun, F. Accuracy of dynamic navigation for immediate and delayed anterior dental implant placement: A retrospective study. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, J.; Yu, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, F. The accuracy of different macrogeometry of dental implant in dynamic navigation guided immediate implant placement in the maxillary aesthetic zone: An in vitro study. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2025, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tahmaseb, A.; Wu, V.; Wismeijer, D.; Coucke, W.; Evans, C. The accuracy of static computer-aided implant surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2018, 29, 416–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, D.; Marquardt, P.; Zwahlen, M.; Jung, R.E. A systematic review on the accuracy and the clinical outcome of computer-guided template-based implant dentistry. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2009, 20, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, J.; Westendorff, C.; Gomez-Roman, G.; Reinert, S. Accuracy of navigation-guided socket drilling before implant installation compared to the conventional free-hand method in a synthetic edentulous lower jaw model. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2005, 16, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, V.; Schulten, E.A.; Helder, M.N.; Ten Bruggenkate, C.M.; Bravenboer, N.; Klein-Nulend, J. Immediate flapless full-arch rehabilitation of edentulous jaws on 4 or 6 implants according to the prosthetic-driven planning and guided implant surgery: A retrospective study on clinical and radiographic outcomes up to 10 years of follow-up. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2022, 24, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaojun, C.; Yanping, L.; Yiqun, W.; Chengtao, W. Computer-aided oral implantology: Methods and applications. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2007, 31, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menchini-Fabris, G.B.; Toti, P.; Covani, U.; Trasarti, S.; Cosola, S.; Crespi, R. Volume assessment of the external contour around immediate implant with or without immediate tooth-like crown provisionalization: A digital intraoral scans study. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 124, 101418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Luo, Y.; Li, B.; Xu, L.; Yang, X.; Man, Y. A Comparative Prospective Study on the Accuracy and Efficiency of Autonomous Robotic System Versus Dynamic Navigation System in Dental Implant Placement. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2025, 52, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Ding, Y.; Cao, R.; Zheng, Y.; Shen, L.; Wang, L.; Yang, F. Accuracy of a Novel Robot-Assisted System and Dynamic Navigation System for Dental Implant Placement: A Clinical Retrospective Study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2025, 36, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Parameter | AR Group (n = 28) | 3D-Printed Group (n = 28) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Entry Error (mm) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 0.42 ± 0.12 | 0.48 ± 0.15 | 0.038 |

| Median (IQR) | 0.41 (0.33–0.49) | 0.46 (0.38–0.57) | |

| Range | 0.21–0.63 | 0.25–0.78 | |

| Total Apex Error (mm) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 0.51 ± 0.18 | 0.58 ± 0.22 | 0.021 |

| Median (IQR) | 0.49 (0.38–0.61) | 0.56 (0.45–0.72) | |

| Range | 0.28–0.89 | 0.31–1.02 | |

| Angular Error (°) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 0.009 |

| Median (IQR) | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | 2.0 (1.6–2.5) | |

| Range | 1.1–3.0 | 1.3–3.5 |

| Implant Position | AR Group Apex Error (mm) | Guide Group Apex Error (mm) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | 0.47 ± 0.14 | 0.53 ± 0.18 | 0.12 |

| 32 | 0.48 ± 0.15 | 0.55 ± 0.19 | 0.08 |

| 42 | 0.52 ± 0.17 | 0.60 ± 0.21 | 0.04 |

| 45 | 0.54 ± 0.19 | 0.63 ± 0.24 | 0.02 |

| Parameter | AR Group | 3D-Printed Group | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry Error (mm) | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.10 |

| Apex Error (mm) | 0.78 | 0.92 | 0.14 |

| Angular Error (°) | 2.5 | 3.1 | 0.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nowicki, A.A.; Markiewicz, M. Comparative Analysis of Implant Placement Accuracy Using Augmented Reality Technology Versus 3D-Printed Surgical Guides: A Controlled In Vitro Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010219

Nowicki AA, Markiewicz M. Comparative Analysis of Implant Placement Accuracy Using Augmented Reality Technology Versus 3D-Printed Surgical Guides: A Controlled In Vitro Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):219. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010219

Chicago/Turabian StyleNowicki, Adam Aleksander, and Marek Markiewicz. 2026. "Comparative Analysis of Implant Placement Accuracy Using Augmented Reality Technology Versus 3D-Printed Surgical Guides: A Controlled In Vitro Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010219

APA StyleNowicki, A. A., & Markiewicz, M. (2026). Comparative Analysis of Implant Placement Accuracy Using Augmented Reality Technology Versus 3D-Printed Surgical Guides: A Controlled In Vitro Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010219