Cetirizine and Dexamethasone in Sepsis: Insights into Maresin-1 Signaling and Cytokine Regulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Surgical Procedures, Sample Collection and Preparation

2.2. Histopathology

2.3. Biochemical Analyses

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

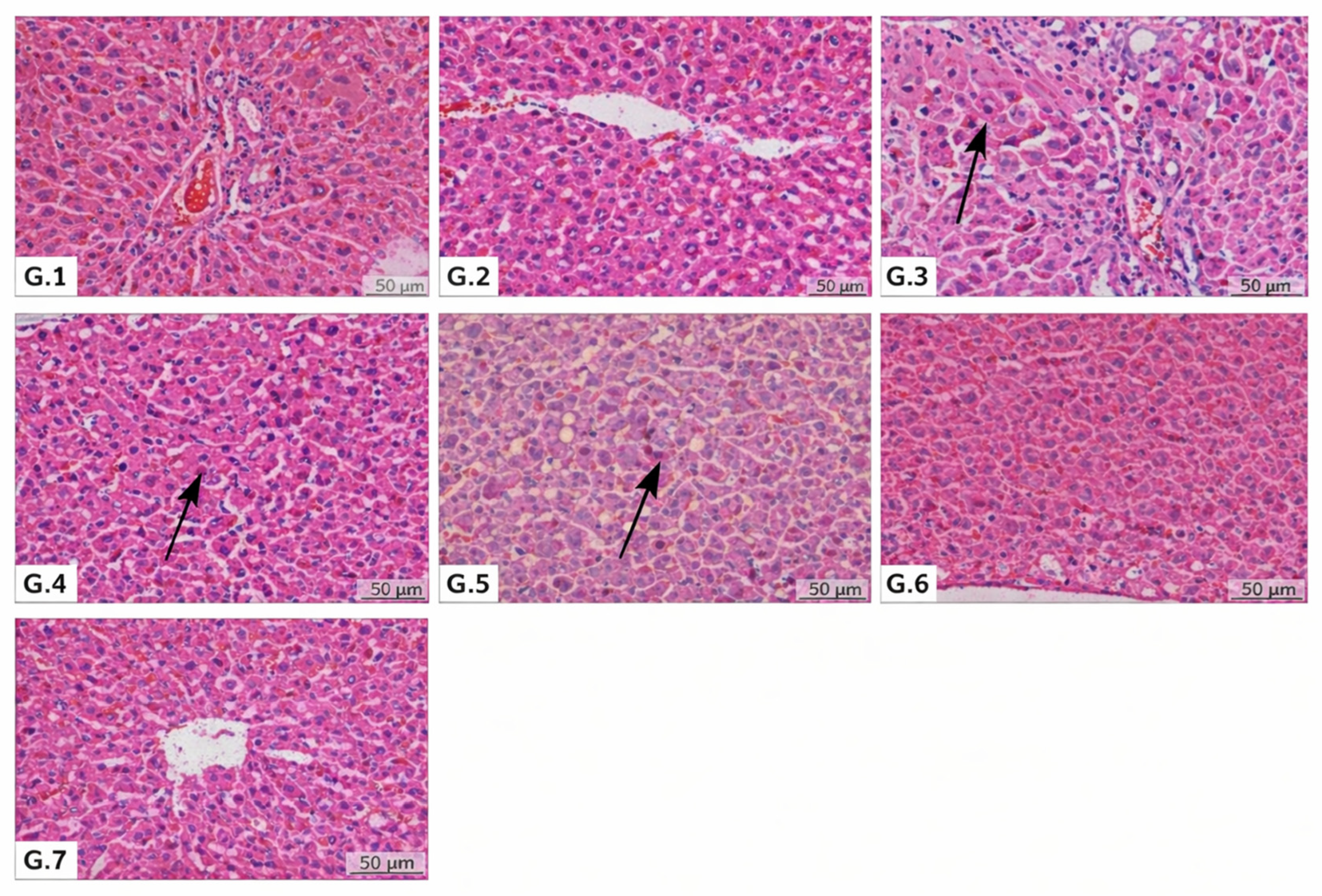

3.1. Histopathological and Hematological Findings

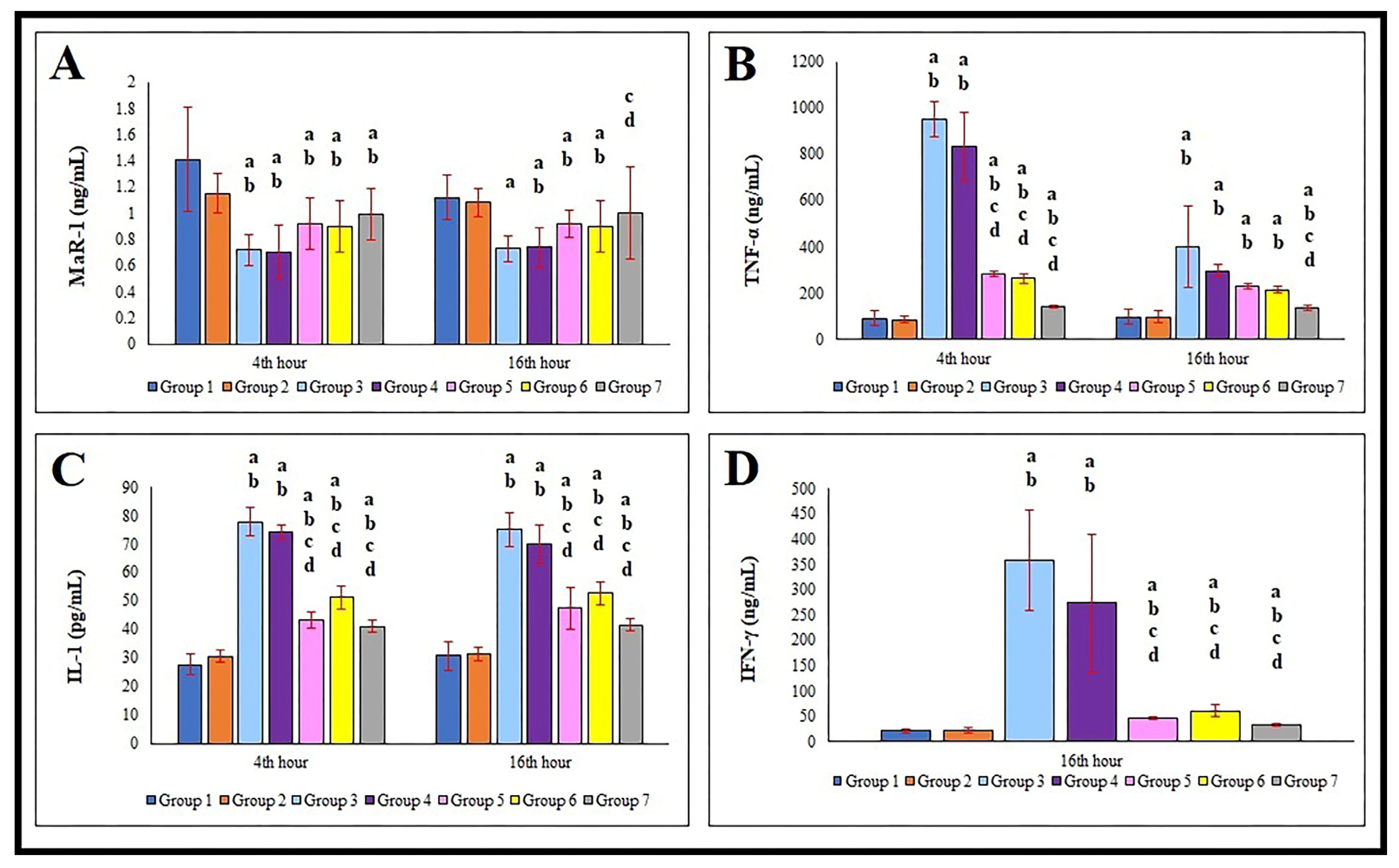

3.2. Serum MaR-1, TNF-α, IL-1, and IFN-γ Levels

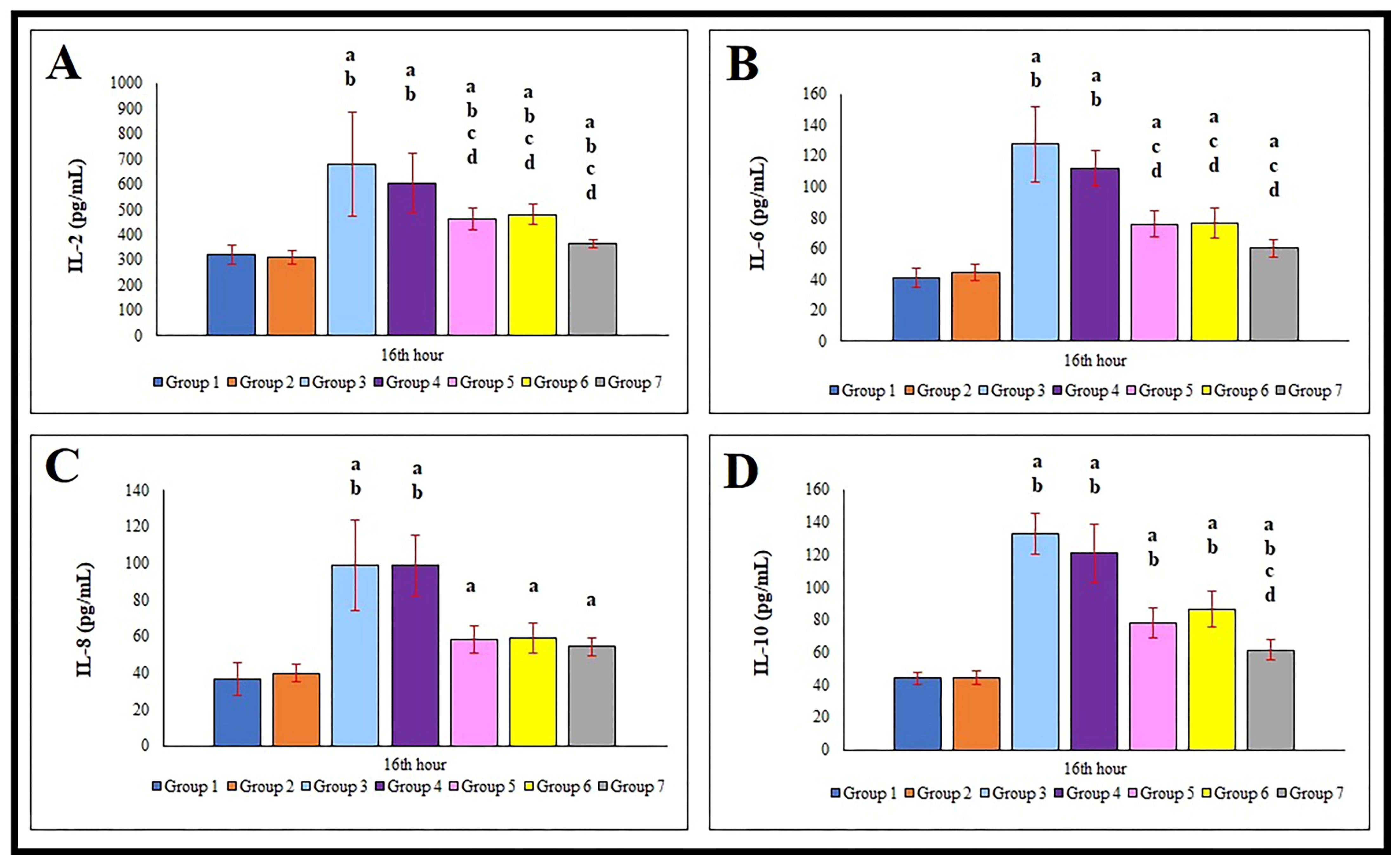

3.3. Serum IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 Levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLP | Cecal ligation and puncture |

| CV | Coefficients of variation |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic acid |

| FÜHADYEK | Fırat University Local Ethics Committee Animal Experiments |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| LYM | Lymphocyte |

| MaR-1 | Maresin-1 |

| MCP | Monocyte chemoattractant protein |

| MO | Monocyte |

| NEU | Neutrophil |

| NK | Natural killer |

| PLT | Platelet |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| WBC | White blood cell |

References

- Dolin, H.H.; Papadimos, T.J.; Chen, X.; Pan, Z.K. Characterization of Pathogenic Sepsis Etiologies and Patient Profiles: A Novel Approach to Triage and Treatment. Microbiol. Insights 2019, 12, 1178636118825081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotchkiss, R.S.; Moldawer, L.L.; Opal, S.M.; Reinhart, K.; Turnbull, I.R.; Vincent, J.L. Sepsis and septic shock. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chousterman, B.G.; Swirski, F.K.; Weber, G.F. Cytokine storm and sepsis disease pathogenesis. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017, 39, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vourc’h, M.; Roquilly, A.; Broquet, A.; David, G.; Hulin, P.; Jacqueline, C.; Caillon, J.; Retiere, C.; Asehnoune, K. Exoenzyme T Plays a Pivotal Role in the IFN-γ Production after Pseudomonas Challenge in IL-12 Primed Natural Killer Cells. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMasters, M.; Mora, J. Addressing Meta-Inflammation in the Comprehensive Management of Chronic Pain. Cureus 2025, 17, e94863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchery, T.; Harris, N. Neutrophil-macrophage cooperation and its impact on tissue repair. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2019, 97, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.C.; Yang, Y.H.; Wang, Y.C.; Chang, W.M.; Wang, C.W. Maresin: Macrophage Mediator for Resolving Inflammation and Bridging Tissue Regeneration—A System-Based Preclinical Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito-Sasaki, N.; Sawada, Y.; Nakamura, M. Maresin-1 and Inflammatory Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, M.; Ye, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Ye, D.; Wan, J. Maresin 1 alleviates the inflammatory response, reduces oxidative stress and protects against cardiac injury in LPS-induced mice. Life Sci. 2021, 277, 119467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtzelis, I.; Hajishengallis, G.; Chavakis, T. Phagocytosis of Apoptotic Cells in Resolution of Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonica, G.W.; Blaiss, M. Antihistaminic, anti-inflammatory, and antiallergic properties of the nonsedating second-generation antihistamine desloratadine: A review of the evidence. World Allergy Organ. J. 2011, 4, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Husain, N.; Anbazhagan, A.N.; Jayawardena, D.; Priyamvada, S.; Singhal, M.; Jain, C.; Kaur, P.; Guzman, G.; Saksena, S.; et al. Dexamethasone Upregulates the Expression of the Human SLC26A3 (DRA, Down-Regulated in Adenoma) Transporter (an IBD Susceptibility Gene) in Intestinal Epithelial Cells and Attenuates Gut Inflammation. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2025, 31, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappia, C.D.; Torralba-Agu, V.; Echeverria, E.; Fitzsimons, C.P.; Fernández, N.; Monczor, F. Antihistamines Potentiate Dexamethasone Anti-Inflammatory Effects. Impact on Glucocorticoid Receptor-Mediated Expression of Inflammation-Related Genes. Cells 2021, 10, 3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, M.; Yamazaki, M.; Ohashi, W.; Tanaka, S.; Hattori, K.; Todoroki, K.; Fujimori, T.; Ohtsu, H.; Matsuda, N.; Hattori, Y. Critical role of endogenous histamine in promoting end-organ tissue injury in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2016, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitre, T.; Drover, K.; Chaudhuri, D.; Zeraaktkar, D.; Menon, K.; Gershengorn, H.B.; Jayaprakash, N.; Spencer-Segal, J.L.; Pastores, S.M.; Nei, A.M.; et al. Corticosteroids in Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Systematic Review, Pairwise, and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care Explor. 2024, 6, e1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, B.A.; Chun, K.P.; Ma, D.; Lythgoe, M.F.; Scott, R.C. Dexamethasone exacerbates cerebral edema and brain injury following lithium-pilocarpine induced status epilepticus. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014, 63, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waage, A. Production and clearance of tumor necrosis factor in rats exposed to endotoxin and dexamethasone. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1987, 45, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, R.; Pei, S.; Yao, S.; Lin, Y.; Yao, C.; Xia, H. Maresin1 prevents sepsis-induced acute liver injury by suppressing NF-κB/Stat3/MAPK pathways, mitigating inflammation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, J.; Bovy, M.A.; Heming, N.; Annane, D. Corticosteroids in sepsis. J. Intensive Med. 2025, 5, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, P.; Blanco, T.; Santiago-Delpín, E.A. Histamine and sympathetic blockade in septic shock. Am. Surg. 1977, 43, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Firzli, T.R.; Sathappan, S.; Antwi-Amoabeng, D.; Beutler, B.D.; Ulanja, M.B.; Madhani-Lovely, F. Association between histamine 2 receptor antagonists and sepsis outcomes in ICU patients: A retrospective analysis using the MIMI-IV database. J. Anesth. Analg. Crit. Care 2023, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, Y. Deneysel sepsis oluşturulan ratlarda deksametazon ve setirizin’in TNF-α, İFN-γ İnterlökin (IL)-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 ve Maresin 1 düzeylerine etkileri. Ph.D. Thesis, Ankara Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Ankara, Türkiye, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wichterman, K.A.; Baue, A.E.; Chaudry, I.H. Sepsis and septic shock—A review of laboratory models and a proposal. J. Surg. Res. 1980, 29, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionov, I.D.; Gorev, N.P.; Roslavtseva, L.A.; Frenkel, D.D. Cetirizine and thalidomide synergistically inhibit mammary tumorigenesis and angiogenesis in 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene-treated rats. Anticancer Drugs 2018, 29, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battiston, F.G.; Dos Santos, C.; Barbosa, A.M.; Sehnem, S.; Leonel, E.C.R.; Taboga, S.R.; Anselmo-Franci, J.A.; Lima, F.B.; Rafacho, A. Glucose homeostasis in rats treated with 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide is not worsened by dexamethasone treatment. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 165, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, S.; Emre, E.; Ugur, K.; Aydin, M.A.; Sahin, İ.; Cinar, V.; Akbulut, T. An overview of ELISA: A review and update on best laboratory practices for quantifying peptides and proteins in biological fluids. J. Int. Med. Res. 2025, 53, 3000605251315913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S. A short history, principles, and types of ELISA, and our laboratory experience with peptide/protein analyses using ELISA. Peptides 2015, 72, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellinger, R.P.; Levy, M.M.; Rhodes, A.; Annane, D.; Gerlach, H.; Opal, S.M.; Sevransky, J.E.; Sprung, C.L.; Douglas, I.S.; Jaeschke, R.; et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013, 39, 165–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, M.C.; Tanyeli, A.; Eraslan, E.; Çomakli, S.; Bayir, Y. Cecal Ligation and Puncture-Induced Sepsis Model in Rats. Lab. Hayv. Bil. Uyg. Derg. 2022, 2, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott, H.C.; Angus, D.C. Enhancing Recovery from Sepsis: A Review. JAMA 2018, 319, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freise, H.; Brückner, U.B.; Spiegel, H.U. Animal models of sepsis. J. Investig. Surg. 2001, 14, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remick, D.G.; Newcomb, D.E.; Bolgos, G.L.; Call, D.R. Comparison of the mortality and inflammatory response of two models of sepsis: Lipopolysaccharide vs. cecal ligation and puncture. Shock 2000, 13, 110–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, M.; Becker, D.E. Thermoregulation: Physiological and clinical considerations during sedation and general anesthesia. Anesth. Prog. 2010, 57, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Léon, K.; Pichavant-Rafini, K.; Ollivier, H.; Monbet, V.; L’Her, E. Does induction time of mild hypothermia influence the survival duration of septic rats? Ther. Hypothermia Temp. Manag. 2015, 5, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Chen, F.; Yu, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Liang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zou, L. Insight into the mechanisms of therapeutic hypothermia for asphyxia cardiac arrest using a comprehensive approach of GC-MS/MS and UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS based on serum metabolomics. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heming, N.; Sivanandamoorthy, S.; Meng, P.; Bounab, R.; Annane, D. Immune Effects of Corticosteroids in Sepsis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, S.; Vardon-Bounes, F.; Merlet-Dupuy, V.; Conil, J.M.; Buléon, M.; Fourcade, O.; Tack, I.; Minville, V. Sepsis modeling in mice: Ligation length is a major severity factor in cecal ligation and puncture. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2016, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Kim, J.; Yu, D.; Park, C.; Park, J. Kinetics of IL-6 and TNF-α changes in a canine model of sepsis induced by endotoxin. Veter. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2012, 146, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, A.; Sawamoto, A.; Okuyama, S.; Nakajima, M. Second-Generation H1-Receptor Antagonists, Mequitazine, Azelastine and Desloratadine Activate Caspase-8, Caspase-3, and Gasdermin E and Induce Cell Death Showing Pyroptotic-Like Features in Macrophages at Excessively High Concentrations. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2025, 48, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S.M.; Lawrence, T.; Kleiman, A.; Warden, P.; Medahalli, M.; Tuckermann, J.; Saklatvala, J.; Clark, A.R. Antiinflammatory effects of dexamethasone are partly dependent on induction of dual specificity phosphatase 1. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 1883–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, A.R.; Dantas, A.T.; Pereira, M.C.; Cordeiro, M.F.; Gonçalves, R.S.G.; de Melo Rêgo, M.J.B.; da Rocha Pitta, I.; Duarte, A.L.B.P.; da Rocha Pitta, M.G. Dexamethasone inhibits cytokine production in PBMC from systemic sclerosis patients. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, H.H.; Grünberg, K.; Derijk, R.H.; Sterk, P.J.; Hiemstra, P.S. Cytokine release and its modulation by dexamethasone in whole blood following exercise. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1998, 111, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.; Liu, A.; Chen, X.; Cheng, W.; Dirsch, O.; Dahmen, U. The severity of LPS induced inflammatory injury is negatively associated with the functional liver mass after LPS injection in rat model. J. Inflamm. 2018, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Zheng, H.; Wang, R.H.; Li, H.; Yang, L.L.; Bhandari, S.; Liu, Y.J.; Han, J.; Smith, F.G.; Gao, H.C.; et al. Maresin1 Alleviates Metabolic Dysfunction in Septic Mice: A 1H NMR-Based Metabolomics Analysis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2019, 2019, 2309175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Ma, M.; Wang, D.; Xie, G.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, P.; Tao, K. Maresin 1 Mitigates Inflammatory Response and Protects Mice from Sepsis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 3798465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Kell, D.B.; Pretorius, E. The Role of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Cell Signalling in Chronic Inflammation. Chronic Stress 2022, 6, 24705470221076390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.Q.; Yao, S.L.; Xia, H.F. Maresin 1 Mitigates Sepsis-Associated Acute Kidney Injury in Mice via Inhibition of the NF-κB/STAT3/MAPK Pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.J.; Jacob, A.; Cunningham, P.; Hensley, L.; Quigg, R.J. TNF is a key mediator of septic encephalopathy acting through its receptor, TNF receptor-1. Neurochem. Int. 2008, 52, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbi, S.; Hao, S.; Epps, J.; Ferreri, N.R. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha at the intersection of renal epithelial and immune cell function. J. Physiol. 2025, 603, 2915–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgül, Y.; Akgül, Ö.; Kozat, S.; Özkan, C.; Kaya, A.; Yılmaz, N. Evaluation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), Interleukins (IL-6, IL-8) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in neonatal calves with presumed septicemia. Van Veter. J. 2019, 30, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.F.; Cao, K.; Jiang, J.P.; Guan, W.X.; Du, J.F. Neutrophil dysregulation during sepsis: An overview and update. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 1687–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, I.C.; Quesada-Vázquez, S.; Sáinz, N.; Guruceaga, E.; Escoté, X.; Moreno-Aliaga, M.J. Effects of Maresin 1 (MaR1) on Colonic Inflammation and Gut Dysbiosis in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybacka-Chabros, B.; Pietrzak, A.; Milanowski, J.; Chabros, P. Influence of prednisone on serum level of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interferon gamma and interleukin-1 beta, in active pulmonary tuberculosis. Pol. J. Public Health 2014, 124, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Fultz, R.S.; Engevik, M.A.; Gao, C.; Hall, A.; Major, A.; Mori-Akiyama, Y.; Versalovic, J. Distinct roles of histamine H1- and H2-receptor signaling pathways in inflammation-associated colonic tumorigenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2019, 31, G205–G216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.I.; Banning, U.; Kim, Y.M.; Verheyen, J.; Hannen, M.; Bönig, H.; Körholz, D. Interleukin 10 inhibits TNF-alpha production in human monocytes independently of interleukin 12 and interleukin 1 beta. Immunol. Investig. 1999, 28, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertowska, P.; Mertowski, S.; Smarz-Widelska, I.; Grywalska, E. Biological Role, Mechanism of Action and the Importance of Interleukins in Kidney Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Zhou, L.; Tian, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, S.; Wang, D.W.; Wei, J. Deep insight into cytokine storm: From pathogenesis to treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okusawa, S.; Gelfand, J.A.; Ikejima, T.; Connolly, R.J.; Dinarello, C.A. Interleukin 1 induces a shock-like state in rabbits. Synergism with tumor necrosis factor and the effect of cyclooxygenase inhibition. J. Clin. Investig. 1988, 81, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Jia, L.; Yang, H.J.; Xue, X.; Xu, W.X.; Cai, J.Q.; Guo, R.J.; Cao, C.C. Taurine enhances the protective effect of Dexmedetomidine on sepsisinduced acute lung injury via balancing the immunological system. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 103, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Malladi, V.S.; von Itzstein, M.S.; Mu-Mosley, H.; Fattah, F.J.; Liu, Y.; Gwin, M.E.; Park, J.Y.; Cole, S.M.; Bhalla, S.; et al. Innate and adaptive immune features associated with immune-related adverse events. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e012414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldrum, D.R.; Ayala, A.; Perrin, M.M.; Ertel, W.; Chaudry, I.H. Diltiazem restores IL-2, IL-3, IL-6, and IFN-gamma synthesis and decreases host susceptibility to sepsis following hemorrhage. J. Surg. Res. 1991, 51, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.; Wang, C.; Smith, R.; Harrison, K.; Yin, K. Role of IFN-gamma in bacterial containment in a model of intra-abdominal sepsis. Shock 2001, 16, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharamti, A.; Samara, O.; Monzon, A.; Scherger, S.; DeSanto, K.; Sillau, S.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Henao-Martínez, A.; Shapiro, L. Association between cytokine levels, sepsis severity and clinical outcomes in sepsis: A quantitative systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.Y.; Ner-Gaon, H.; Varon, J.; Cullen, A.M.; Guo, J.; Choi, J.; Barragan-Bradford, D.; Higuera, A.; Pinilla-Vera, M.; Short, S.A.; et al. Post-sepsis immunosuppression depends on NKT cell regulation of mTOR/IFN-γ in NK cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 3238–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wu, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Du, Y.; Liu, Y.; Song, K.; Shi, Q.; Li, R. Increased TLR4 Expression Aggravates Sepsis by Promoting IFN-γ Expression in CD38−/− Mice. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 3737890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, C.R.; Herzig, D.S.; Etogo, A.; Nunez, J.; Mahmoudizad, R.; Fang, G.; Murphey, E.D.; Toliver-Kinsky, T.; Sherwood, E.R. The role of interferon-γ in the pathogenesis of acute intra-abdominal sepsis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010, 88, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigante, M.; Ranieri, E. In vitro\ex vivo generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1186, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, W.J.; Depper, J.M.; Crabtree, G.R.; Rudikoff, S.; Pumphrey, J.; Robb, R.J.; Krönke, M.; Svetlik, P.B.; Peffer, N.J.; Waldmann, T.A.; et al. Molecular cloning and expression of cDNAs for the human interleukin-2 receptor. Nature 1984, 311, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M.F.; Kopf, M. Balancing protective immunity and immunopathology. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2002, 14, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kong, Q.; Fan, J.; Zhao, H. Interleukin-2 and its receptors: Implications and therapeutic prospects in immune-mediated disorders of central nervous system. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 213, 107658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, S.; Inada, K.; Inoue, Y. Two types of septic shock classified by the plasma levels of cytokines and endotoxin. Circ. Shock 1992, 38, 264–274. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, H.; Yin, Y.L.; Guo, W.Z.; Ma, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.B.; Shu, C.; Dong, L.Q. Role of interleukin-6 to differentiate sepsis from non-infectious systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Cytokine 2016, 88, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Park, D.W.; Moon, S.; Cho, H.J.; Park, J.H.; Seok, H.; Choi, W.S. Diagnostic and prognostic value of interleukin-6, pentraxin 3, and procalcitonin levels among sepsis and septic shock patients: A prospective controlled study according to the Sepsis-3 definitions. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spittler, A.; Razenberger, M.; Kupper, H.; Kaul, M.; Hackl, W.; Boltz-Nitulescu, G.; Függer, R.; Roth, E. Relationship between interleukin-6 plasma concentration in patients with sepsis, monocyte phenotype, monocyte phagocytic properties, and cytokine production. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 31, 1338–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schüttler, J.; Neumann, S. Interleukin-6 as a prognostic marker in dogs in an intensive care unit. Veter. Clin. Pathol. 2015, 44, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badea, I.M.; Azamfirei, R.; Grigorescu, B.L.; Ráduly, G.; Hutanu, A.; Petrişor, M.; Lazăr, A.E.; Almásy, E.; Fodor, R.Ş.; Man, A.; et al. The role of interleukin-6 as an early predictor of sepsis in a murine sepsis model. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2019, 60, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, S.; Ma, T.; Di, X.; Tian, C.; Zhao, M.; Wang, K. Diagnostic value of neutrophil CD64, procalcitonin, and interleukin-6 in sepsis: A meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.L.; Fitzgerald, J.C.; Laskin, B.L.; Singh, R.; Artis, A.S.; Vohra, A.; Tsemberis, E.; Kierian, E.; Lau, K.C.; Campos, A.B.; et al. Time Course of Kidney Injury Biomarkers in Children with Septic Shock: Nested Cohort Study Within the Pragmatic Pediatric Trial of Balanced Versus Normal Saline Fluid in Sepsis Trial. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 26, e816–e826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbarth, S.; Holeckova, K.; Froidevaux, C.; Pittet, D.; Ricou, B.; Grau, G.E.; Vadas, L.; Pugin, J.; Geneva Sepsis Network. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 in critically ill patients admitted with suspected sepsis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 164, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Huai, L.; Shi, B.; Zhang, D.; Xu, W.; Cui, D. Interleukin-6 related signaling pathways as the intersection between chronic diseases and sepsis. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hack, C.E.; Hart, M.; van Schijndel, R.J.; Eerenberg, A.J.; Nuijens, J.H.; Thijs, L.G.; Aarden, L.A. Interleukin-8 in sepsis: Relation to shock and inflammatory mediators. Infect. Immun. 1992, 60, 2835–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.C.; da Fe Silveira, L.; Viegas, K.; Beck, A.D.; Júnior, G.F.; Cremonese, R.V.; Lora, P.S. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in the early diagnosis of sepsis in an intensive care unit: A case-control study. Rev. Bras. Ter. Intensiv. 2019, 31, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naess, A.; Nilssen, S.S.; Mo, R.; Eide, G.E.; Sjursen, H. Role of neutrophil to lymphocyte and monocyte to lymphocyte ratios in the diagnosis of bacterial infection in patients with fever. Infection 2017, 45, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, E.; Romero, R.; Suksai, M.; Gotsch, F.; Chaemsaithong, P.; Erez, O.; Conde-Agudelo, A.; Gomez-Lopez, N.; Berry, S.M.; Meyyazhagan, A.; et al. Clinical chorioamnionitis at term: Definition, pathogenesis, microbiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, S807–S840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, R.; Herndon, D.N.; Finnerty, C.C.; Cox, R.A.; Song, J.; Jeschke, M.G. Predictive Value of IL-8 for Sepsis and Severe Infections After Burn Injury: A Clinical Study. Shock 2015, 43, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberholzer, A.; Oberholzer, C.; Moldawer, L.L. Interleukin-10: A complex role in the pathogenesis of sepsis syndromes and its potential as an anti-inflammatory drug. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 30, S58–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Tang, Z.; Xu, J.; Ge, W.; Hu, Q.; He, F.; Zheng, G.; Jiang, L.; Yang, Z.; Tang, W. The inhibitor of interleukin-3 receptor protects against sepsis in a rat model of cecal ligation and puncture. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 109, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzavacca, P.; Lankadeva, Y.R.; Bailey, S.R.; Bailey, M.; Bellomo, R.; May, C.N. Effects of selective β1-adrenoceptor blockade on cardiovascular and renal function and circulating cytokines in ovine hyperdynamic sepsis. Crit. Care 2014, 18, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutai, A.; Zsikai, B.; Tallósy, S.P.; Érces, D.; Bizánc, L.; Juhász, L.; Poles, M.Z.; Sóki, J.; Baaity, Z.; Fejes, R.; et al. A Porcine Sepsis Model with Numerical Scoring for Early Prediction of Severity. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 867796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senousy, S.R.; Ahmed, A.F.; Abdelhafeez, D.A.; Khalifa, M.M.A.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; El-Daly, M. Alpha-Chymotrypsin Protects Against Acute Lung, Kidney, and Liver Injuries and Increases Survival in CLP-Induced Sepsis in Rats Through Inhibition of TLR4/NF-κB Pathway. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2022, 16, 3023–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbia, D.; Pozzo, L.; Zigiotto, G.; Roverso, M.; Sacchi, D.; Pozza, A.D.; Carrara, M.; Bogialli, S.; Floreani, A.; Guido, M.; et al. Dexamethasone counteracts hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress in cholestatic rats via CAR activation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska-Woda, I.; Bieszczad-Bedrejczuk, E.; Rachel, M. Influence of desloratadine on selected oxidative stress markers in patients between 3 and 10 years of age with allergic perennial rhinitis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 640, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Experiment Group | Just Before to Start Experiment | 4th Hour After Experiment Started | 16th Hour After Experiment Started |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 (n: 7) | 37.14 ± 0.18 | 37.14 ± 0.18 | 37.13 ± 0.19 |

| G2 (n: 7) | 37.24 ± 0.08 | 36.74 ± 0.52 | 37.24 ± 0.25 |

| G3 (n: 7) | 37.25 ± 0.19 | 35.65 ± 0.62 a | 38.36 ± 0.26 |

| G4 (n: 7) | 37.06 ± 0.24 | 36.08 ± 0.53 | 38.70 ± 0.23 b,f |

| G5 (n: 7) | 36.97 ± 0.39 | 35.91 ± 0.76 c | 38.48 ± 0.17 |

| G6 (n: 7) | 37.14 ± 0.21 | 35.98 ± 0.26 d | 38.50 ± 0.28 d |

| G7 (n: 7) | 37.10 ± 0.16 | 36.07 ± 0.25 e | 38.36 ± 0.31 |

| Parameter | G1 (n: 7) | G2 (n: 7) | G3 (n: 7) | G4 (n: 7) | G5 (n: 7) | G6 (n: 7) | G7 (n: 7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammation | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.02 ± 0.01 a | 2.17 ± 0.41 a | 1.20 ± 0.45 a | 1.29 ± 0.49 b | 1.83 ± 0.75 b | 1.86 ± 1.07 a |

| Necrosis | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 a | 2.83 ± 0.75 a | 2.57 ± 0.79 a | 2.43 ± 0.53 a | 2.33 ± 0.82 a | 2.20 ± 0.84 a |

| Congestion | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 a | 2.50 ± 0.84 a | 2.43 ± 0.53 a | 2.14 ± 0.69 a | 1.67 ± 0.82 b,c,d | 1.80 ± 0.84a |

| Kupffer activation | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 a | 3.00 ± 0.00 a | 2.14 ± 0.38 a,b | 2.00 ± 0.68 a,b | 2.67 ± 0.52 a,b | 2.20 ± 0.45 a,b |

| Time | G | WBC (mm3/μL) | NEU (mm3/μL) | LYM (mm3/μL) | MO (mm3/μL) | PLT (mm3/μL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4th hour | G1 (n: 7) | 6.75 ± 1.66 | 4.48 ± 1.17 | 2.84 ± 0.92 | 0.49 ± 0.18 | 252.74 ± 62.14 |

| G2 (n: 7) | 6.67 ± 1.11 | 4.36 ± 1.22 | 2.77 ± 0.74 | 0.46 ± 0.22 | 247.42 ± 62.11 | |

| G3 (n: 7) | 8.88 ± 1.74 a,b | 5.28 ± 1.42 a,b | 2.23 ± 0.86 a,b | 0.54 ± 0.28 | 387.12 ± 76.22 a,b | |

| G4 (n: 7) | 8.72 ± 1.88 a,b | 5.32 ± 1.56 a,b | 2.27 ± 0.82 a,b | 0.48 ± 0.22 | 398.16 ± 84.46 a,b | |

| G5 (n: 7) | 8.74 ± 1.88 a,b | 5.01 ± 1.44 b | 2.38 ± 0.76 a | 0.46 ± 0.32 | 374.22 ± 68.86 a,b | |

| G6 (n: 7) | 8.66 ± 1.44 a,b | 4.98 ± 1.68 b | 2.42 ± 0.98 | 0.42 ± 0.22 | 372.66 ± 72.94 a,b | |

| G7 (n: 7) | 8.52 ± 1.68 b | 4.78 ± 1.62 | 2.48 ± 0.66 | 0.47 ± 0.18 | 368.62 ± 83.66 | |

| 16th hour | G1 (n: 7) | 6.67 ± 1.34 | 4.40 ± 0.92 | 2.92 ± 0.84 | 0.47 ± 0.17 | 247.74 ± 51.09 |

| G2 (n: 7) | 6.42 ± 1.30 | 4.37 ± 0.92 | 2.78 ± 0.62 | 0.45 ± 0.28 | 236.52 ± 48.12 | |

| G3 (n: 7) | 9.18 ± 1.92 a,b | 5.78 ± 1.12 a,b | 1.98 ± 0.60 a,b | 0.62 ± 0.26 | 424.29 ± 92.38 a,b | |

| G4 (n: 7) | 9.02 ± 2.13 a,b | 5.82 ± 1.42 a,b | 2.02 ± 0.68 a,b | 0.59 ± 0.20 | 428. 02 ± 93.18 a,b | |

| G5 (n: 7) | 8.96 ± 1.76 a,b | 5.56 ± 1.72 a,b | 2.52 ± 0.83 | 0.53 ± 0.38 | 402.22 ± 63.17 b | |

| G6 (n: 7) | 8.86 ± 1.44 b | 5.64 ± 1.56 a,b | 2.48 ± 0.92 | 0.51 ± 0.26 | 412.21 ± 81.14 a,b | |

| G7 (n: 7) | 8.76 ± 1.80 b | 5.28 ± 1.74 | 2.62 ± 0.66 c,d | 0.50 ± 0.19 | 398.18 ± 77.42 b |

| Positive Related Groups | r Value | p Value | Negative Related Groups | r Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BT (16 h)–TNF-α (4 h) | +0.836 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (4 h)–TNF-α (4 h) | −0.904 | 0.000 |

| MaR-1 (4 h)–MaR-1 (16 h) | +0.962 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (4 h)–IL-1 (4 h) | −0.960 | 0.000 |

| TNF-α (4 h)–IL-1 (4 h) | +0.931 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (4 h)–TNF-α (16 h) | −0.891 | 0.000 |

| TNF-α (4 h)–TNF-α (16 h) | +0.974 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (4 h)–IFN-γ (16 h) | −0.929 | 0.000 |

| TNF-α (4 h)–IFN-γ (16 h) | +0.914 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (4 h)–IL-2 (16 h) | −0.953 | 0.000 |

| TNF-α (4 h)–IL-1 (16 h) | +0.914 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (4 h)–IL-6 (16 h) | −0.923 | 0.000 |

| TNF-α (4 h)–IL-2 (16 h) | +0.890 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (4 h)–IL-8 (16 h) | −0.923 | 0.000 |

| TNF-α (4 h)–IL-6 (16 h) | +0.892 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (4 h)–IL-10 (16 h) | −0.935 | 0.000 |

| TNF-α (4 h)–IL-8 (16 h) | +0.937 | 0.000 | TNF-α (4 h)–MaR-1 (16 h) | −0.913 | 0.000 |

| TNF-α (4 h)–IL-10 (16 h) | +0.901 | 0.000 | IL-1 (4 h)–MaR-1 (16 h) | −0.948 | 0.000 |

| IL-1 (4 h)–TNF-α (16 h) | +0.917 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (16 h)–TNF-α (16 h) | −0.882 | 0.000 |

| IL-1 (4 h)–IFN-γ (16 h) | +0.949 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (16 h)–IFN-γ (16 h) | −0.924 | 0.000 |

| IL-1 (4 h)–IL-1 (16 h) | +0.992 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (16 h)–IL-1 (16 h) | −0.940 | 0.000 |

| IL-1 (4 h)–IL-2 (16 h) | +0.934 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (16 h)–IL-2 (16 h) | −0.917 | 0.000 |

| IL-1 (4 h)–IL-6 (16 h) | +0.938 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (16 h)–IL-6 (16 h) | −0.891 | 0.000 |

| IL-1 (4 h)–IL-8 (16 h) | +0.937 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (16 h)–IL-8 (16 h) | −0.881 | 0.000 |

| IL-1 (4 h)–IL-10 (16. h) | +0.923 | 0.000 | MaR-1 (16 h)–IL-10 (16 h) | −0.920 | 0.000 |

| TNF-α (16 h)–IFN-γ (16 h) | +0.862 | 0.000 | |||

| TNF-α (16 h)–IL-1 (16 h) | +0.892 | 0.000 | |||

| TNF-α (16 h)–IL-2 (16 h) | +0.871 | 0.000 | |||

| TNF-α (16 h)–IL-6 (16 h) | +0.864 | 0.000 | |||

| TNF-α (16 h)–IL-8 (16 h) | +0.916 | 0.000 | |||

| TNF-α (16 h)–IL-10 (16 h) | +0.959 | 0.000 | |||

| IFN-γ (16 h)–IL-1 (16 h) | +0.946 | 0.000 | |||

| IFN-γ (16 h)–IL-2 (16 h) | +0.915 | 0.000 | |||

| IFN-γ (16 h)–IL-8 (16 h) | +0.884 | 0.000 | |||

| IFN-γ (16 h)–IL-10 (16 h) | +0.959 | 0.000 | |||

| IL-1 (16 h)–IL-2 (16 h) | +0.904 | 0.000 | |||

| IL-1 (16 h)–IL-6 (16 h) | +0.947 | 0.000 | |||

| IL-1 (16 h)–IL-8 (16 h) | +0.927 | 0.000 | |||

| IL-1 (16 h)–IL-10 (16 h) | +0.951 | 0.000 | |||

| IL-2 (16 h)–IL-6 (16 h) | +0.902 | 0.000 | |||

| IL-2 (16 h)–IL-8 (16 h) | +0.902 | 0.000 | |||

| IL-2 (16 h)–IL-10 (16 h) | +0.886 | 0.000 | |||

| IL-6 (16 h)–IL-8 (16 h) | +0.900 | 0.000 | |||

| IL-6 (16 h)–IL-10 (16 h) | +0.929 | 0.000 | |||

| IL-8 (16 h)–IL-10 (16 h) | +0.881 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aydin, Y.; Borku, M.K.; Ugur, K.; Eroksuz, Y.; Emre, E.; Incili, C.A.; Sahin, İ.; Acarturk, İ.Z.; Aydin, S.; Lee, D.-Y. Cetirizine and Dexamethasone in Sepsis: Insights into Maresin-1 Signaling and Cytokine Regulation. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010198

Aydin Y, Borku MK, Ugur K, Eroksuz Y, Emre E, Incili CA, Sahin İ, Acarturk İZ, Aydin S, Lee D-Y. Cetirizine and Dexamethasone in Sepsis: Insights into Maresin-1 Signaling and Cytokine Regulation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010198

Chicago/Turabian StyleAydin, Yalcin, Mehmet Kazim Borku, Kader Ugur, Yesari Eroksuz, Elif Emre, Canan Akdeniz Incili, İbrahim Sahin, İlknur Zeynep Acarturk, Suleyman Aydin, and Do-Youn Lee. 2026. "Cetirizine and Dexamethasone in Sepsis: Insights into Maresin-1 Signaling and Cytokine Regulation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010198

APA StyleAydin, Y., Borku, M. K., Ugur, K., Eroksuz, Y., Emre, E., Incili, C. A., Sahin, İ., Acarturk, İ. Z., Aydin, S., & Lee, D.-Y. (2026). Cetirizine and Dexamethasone in Sepsis: Insights into Maresin-1 Signaling and Cytokine Regulation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010198