Artificial Intelligence in Intensive Care: An Overview of Systematic Reviews with Clinical Maturity and Readiness Mapping

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Reporting Framework

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

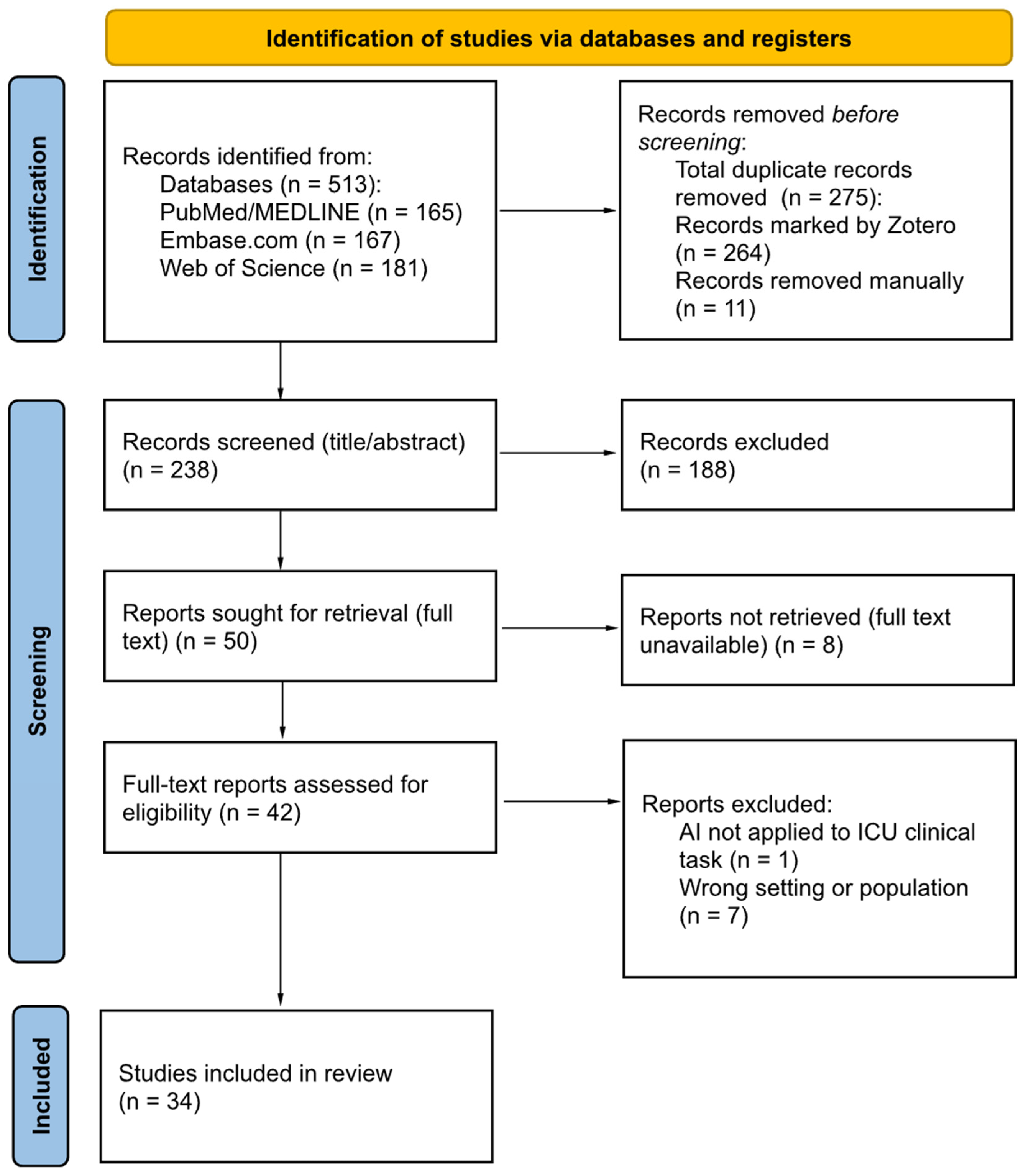

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction and Data Items

2.6. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

2.7. Handling Overlap and Discordance

2.8. Assessment of Evidence and Implementation Maturity

2.9. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection Results

3.2. Characteristics of Included Reviews

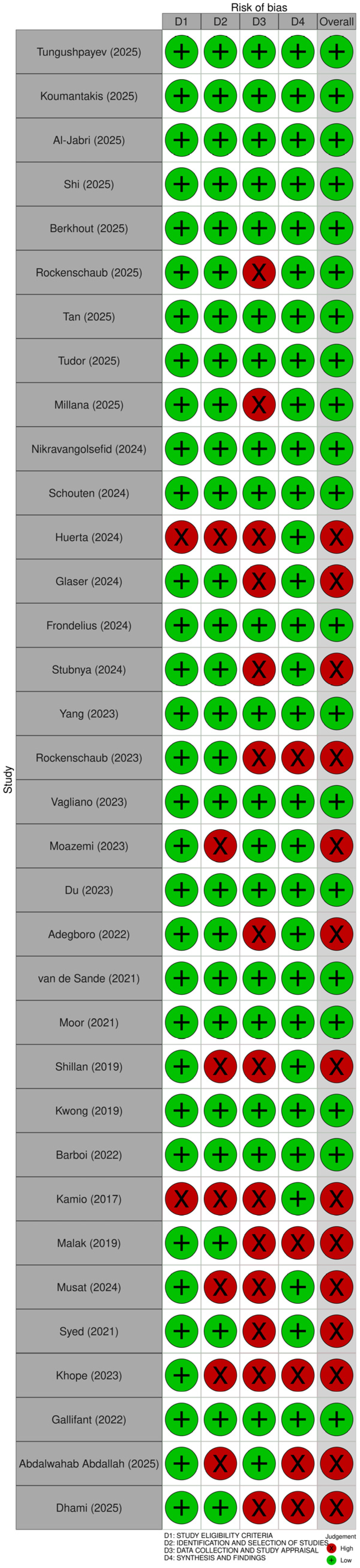

3.3. Quality Assessment of Included Reviews

3.4. Results by Clinical Domain (SWiM Core)

3.4.1. Clinical Domain: Prognostic and Early Warning Models (SWiM)

3.4.2. Clinical Domain: Diagnostic and Detection Models (SWiM)

3.4.3. Clinical Domain: Monitoring and Dynamic Assessment Models (SWiM)

3.4.4. Clinical Domain: Treatment Support and Decision Support Models (SWiM)

3.4.5. Clinical Domain: Implementation and Readiness Focused Reviews (SWiM)

3.4.6. Cross-Domain Evidence and Implementation Maturity Signals Within Included Reviews

3.4.7. Overlap-Light and Discordance Signals

3.5. Evidence and Implementation Maturity Results

3.5.1. Maturity Mapping: Prognostic and Early Warning Models

3.5.2. Maturity Mapping: Diagnostic and Detection Models

3.5.3. Maturity Mapping: Monitoring and Dynamic Assessment Models

3.5.4. Treatment Support and Decision Support Models

3.5.5. Implementation and Readiness Focused Reviews

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Interpretation in Context

4.3. Clinical Maturity and Implications

4.4. Gaps and Future Directions

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ML | Machine learning |

| PRIOR | A reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions |

| SWiM | Synthesis without meta-analysis in systematic reviews: reporting guideline |

| EHR | Electronic health record |

| NICU | Neonatal intensive care unit |

| PICU | Pediatric intensive care unit |

| CICU | Cardiac intensive care unit |

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

References

- Berkhout, W.E.M.; van Wijngaarden, J.J.; Workum, J.D.; van de Sande, D.; Hilling, D.E.; Jung, C.; Meyfroidt, G.; Gommers, D.; Buijsman, S.N.R.; van Genderen, M.E. Operationalization of Artificial Intelligence Applications in the Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2522866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tungushpayev, M.; Suleimenova, D.; Sarria-Santamerra, A.; Aimyshev, T.; Gaipov, A.; Viderman, D. The Value of Machine and Deep Learning in Management of Critically Ill Patients: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2025, 204, 106081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalimouttou, A.; Stevens, R.D.; Pirracchio, R. Harnessing AI in Critical Care: Opportunities, Challenges and Key Steps for Success. Thorax, 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Sande, D.; Van Genderen, M.E.; Huiskens, J.; Gommers, D.; Van Bommel, J. Moving from Bytes to Bedside: A Systematic Review on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in the Intensive Care Unit. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agard, G.; Hraiech, S.; Gauss, T. From Promise to Practice: A Roadmap for Artificial Intelligence in Critical Care. J. Crit. Care 2026, 91, 155263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workum, J.D.; Meyfroidt, G.; Bakker, J.; Jung, C.; Tobin, J.M.; Gommers, D.; Elbers, P.W.G.; van der Hoeven, J.G.; Van Genderen, M.E. AI in Critical Care: A Roadmap to the Future. J. Crit. Care 2026, 91, 155262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, M.; Gates, A.; Pieper, D.; Fernandes, R.M.; Tricco, A.C.; Moher, D.; Brennan, S.E.; Li, T.; Pollock, M.; Lunny, C.; et al. Reporting Guideline for Overviews of Reviews of Healthcare Interventions: Development of the PRIOR Statement. BMJ 2022, 378, e070849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadweh, P.; Niset, A.; Salvagno, M.; Al Barajraji, M.; El Hadwe, S.; Taccone, F.S.; Barrit, S. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Intensive Care Medicine: Critical Recalibrations from Rule-Based Systems to Frontier Models. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moralez, G.M.; Amado, F.; Liu, V.X.; Tan, S.C.; Meyfroidt, G.; Stevens, R.D.; Pilcher, D.; Salluh, J.I.F. Data-Driven Quality of Care in the ICU: A Concise Review. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 53, e2720–e2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, M.; Caruso, P.F.; Cecconi, M. Artificial Intelligence in the Intensive Care Unit. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 42, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Sowden, A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Brennan, S.E.; Ellis, S.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Ryan, R.; Shepperd, S.; Thomas, J.; et al. Synthesis without Meta-Analysis (SWiM) in Systematic Reviews: Reporting Guideline. BMJ 2020, 368, l6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koumantakis, E.; Remoundou, K.; Colombi, N.; Fava, C.; Roussaki, I.; Visconti, A.; Berchialla, P. Deep Learning Models for ICU Readmission Prediction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabri, M.M.; Anshasi, H. Performance of Machine and Deep Learning Models for Predicting Delirium in Adult ICU Patients: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2025, 203, 106008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, T.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, H.; Kong, G. Artificial Intelligence Models for Predicting Acute Kidney Injury in the Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review of Modeling Methods, Data Utilization, and Clinical Applicability. JAMIA Open 2025, 8, ooaf065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockenschaub, P.; Akay, E.M.; Carlisle, B.G.; Hilbert, A.; Wendland, J.; Meyer-Eschenbach, F.; Näher, A.-F.; Frey, D.; Madai, V.I. External Validation of AI-Based Scoring Systems in the ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2025, 25, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.; Ge, C.; Li, Z.; Yan, Y.; Guo, H.; Song, W.; Zhu, Q.; Du, Q. Early Prediction of Mortality Risk in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e70537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, S.; Bhatia, R.; Liem, M.; Wani, T.A.; Boyd, J.; Khan, U.R. Opportunities and Challenges of Using Artificial Intelligence in Predicting Clinical Outcomes and Length of Stay in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e63175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millana, A.M.; Solaz-García, Á.; Montaner, A.G.; Portolés-Morales, M.; Xiao, L.; Sun, Y.; Traver, V.; Vento, M.; Sáenz-González, P. A Systematic Review on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: Far beyond the Potential Impact. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2025, 30, 101690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikravangolsefid, N.; Reddy, S.; Truong, H.H.; Charkviani, M.; Ninan, J.; Prokop, L.J.; Suppadungsuk, S.; Singh, W.; Kashani, K.B.; Garces, J.P.D. Machine Learning for Predicting Mortality in Adult Critically Ill Patients with Sepsis: A Systematic Review. J. Crit. Care 2024, 84, 154889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, J.S.; Kalden, M.A.C.M.; Van Twist, E.; Reiss, I.K.M.; Gommers, D.A.M.P.J.; Van Genderen, M.E.; Taal, H.R. From Bytes to Bedside: A Systematic Review on the Use and Readiness of Artificial Intelligence in the Neonatal and Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 1767–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, N.; Rao, S.J.; Isath, A.; Wang, Z.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Krittanawong, C. The Premise, Promise, and Perils of Artificial Intelligence in Critical Care Cardiology. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 86, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, K.; Marino, L.; Stubnya, J.D.; Bilotta, F. Machine Learning in the Prediction and Detection of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in ICU: A Systematic Review. J. Anesth. 2024, 38, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frondelius, T.; Atkova, I.; Miettunen, J.; Rello, J.; Vesty, G.; Chew, H.S.J.; Jansson, M. Early Prediction of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia with Machine Learning Models: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prediction Model Performance✰. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 121, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubnya, J.D.; Marino, L.; Glaser, K.; Bilotta, F. Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Admitted to the ICU with Sepsis: A Systematic Review of Clinical Evidence. J. Crit. Intensive Care 2024, 15, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Cui, X.; Song, Z. Predicting Sepsis Onset in ICU Using Machine Learning Models: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockenschaub, P.; Akay, E.M.; Carlisle, B.G.; Hilbert, A.; Meyer-Eschenbach, F.; Näher, A.-F.; Frey, D.; Madai, V.I. Generalisability of AI-Based Scoring Systems in the ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagliano, I.; Dormosh, N.; Rios, M.; Luik, T.T.; Buonocore, T.M.; Elbers, P.W.G.; Dongelmans, D.A.; Schut, M.C.; Abu-Hanna, A. Prognostic Models of In-Hospital Mortality of Intensive Care Patients Using Neural Representation of Unstructured Text: A Systematic Review and Critical Appraisal. J. Biomed. Inform. 2023, 146, 104504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazemi, S.; Vahdati, S.; Li, J.; Kalkhoff, S.; Castano, L.J.V.; Dewitz, B.; Bibo, R.; Sabouniaghdam, P.; Tootooni, M.S.; Bundschuh, R.A.; et al. Artificial Intelligence for Clinical Decision Support for Monitoring Patients in Cardiovascular ICUs: A Systematic Review. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1109411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.H.; Guan, C.J.; Li, L.Y.; Gan, P. Predictive Value of Machine Learning for the Risk of Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) in Hospital Intensive Care Units (ICU) Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegboro, C.O.; Choudhury, A.; Asan, O.; Kelly, M.M. Artificial Intelligence to Improve Health Outcomes in the NICU and PICU: A Systematic Review. Hosp. Pediatr. 2022, 12, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moor, M.; Rieck, B.; Horn, M.; Jutzeler, C.R.; Borgwardt, K. Early Prediction of Sepsis in the ICU Using Machine Learning: A Systematic Review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 607952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shillan, D.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Champneys, A.; Gibbison, B. Use of Machine Learning to Analyse Routinely Collected Intensive Care Unit Data: A Systematic Review. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, M.T.; Colopy, G.W.; Weber, A.M.; Ercole, A.; Bergmann, J.H.M. The Efficacy and Effectiveness of Machine Learning for Weaning in Mechanically Ventilated Patients at the Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review. Bio-Des. Manuf. 2019, 2, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboi, C.; Tzavelis, A.; Muhammad, L.N. Comparison of Severity of Illness Scores and Artificial Intelligence Models That Are Predictive of Intensive Care Unit Mortality: Meta-Analysis and Review of the Literature. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022, 10, e35293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamio, T.; Van, T.; Masamune, K. Use of Machine-Learning Approaches to Predict Clinical Deterioration in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 2017, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Malak, J.; Zeraati, H.; Nayeri, F.; Safdari, R.; Shahraki, A. Neonatal Intensive Care Decision Support Systems Using Artificial Intelligence Techniques: A Systematic Review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2019, 52, 2685–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mușat, F.; Păduraru, D.N.; Bolocan, A.; Palcău, C.A.; Copăceanu, A.-M.; Ion, D.; Jinga, V.; Andronic, O. Machine Learning Models in Sepsis Outcome Prediction for ICU Patients: Integrating Routine Laboratory Tests—A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, M.; Syed, S.; Sexton, K.; Syeda, H.B.; Garza, M.; Zozus, M.; Syed, F.; Begum, S.; Syed, A.U.; Sanford, J.; et al. Application of Machine Learning in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Settings Using MIMIC Dataset: Systematic Review. Informatics 2021, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khope, S.; Elias, S. Strategies of Predictive Schemes and Clinical Diagnosis for Prognosis Using MIMIC-III: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallifant, J.; Zhang, J.; Del Pilar Arias Lopez, M.; Zhu, T.; Camporota, L.; Celi, L.A.; Formenti, F. Artificial Intelligence for Mechanical Ventilation: Systematic Review of Design, Reporting Standards, and Bias. Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 128, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalwahab Abdallah, A.B.A.; Hafez Sadaka, S.I.; Ali, E.I.; Mustafa Bilal, S.A.; Abdelrahman, M.O.; Fakiali Mohammed, F.B.; Nimir Ahmed, S.D.; Abdelrahim Saeed, N.E. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Pediatric Intensive Care: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e80142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhami, A.; Onyeukwu, K.A.; Sattar, S.; Batra, A.; Mostafa, Y.; Haris, M.; Iqbal, A.; Bokhari, S.F.H.; Siddique, M.U. The Prognostic Performance of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Models for Mortality Prediction in Intensive Care Units: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e90465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/2016-05-04/eng (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare—Public Health—European Commission. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/artificial-intelligence-healthcare_en (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- European Health Data Space Regulation (EHDS)—Public Health. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/european-health-data-space-regulation-ehds_en (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Artificial Intelligence Board (AIB); Medical Device Coordination Group (MDCG). AIB 2025-1/MDCG 2025-6: Interplay between the Medical Devices Regulation (MDR) and In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices Regulation (IVDR) and the Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA). June 2025. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/b78a17d7-e3cd-4943-851d-e02a2f22bbb4_en?filename=mdcg_2025-6_en.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Medical Device Coordination Group (MDCG). MDCG 2019-11 rev.1: Qualification and Classification of Software Under Regulation (EU) 2017/745 (MDR) and Regulation (EU) 2017/746 (IVDR); Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety, European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/latest-updates/update-mdcg-2019-11-rev1-qualification-and-classification-software-regulation-eu-2017745-and-2025-06-17_en (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Sallam, D.M.; Snygg, D.J.; Allam, D.D.; Kassem, D.R.; Damani, D.M. Artificial Intelligence in Clinical Medicine: A SWOT Analysis of AI Progress in Diagnostics, Therapeutics, and Safety. J. Innov. Med. Res. 2025, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Aim of Study | Domain(s) (Multilabel) | Population Type | Data Modality | Validation Approach | Implementation/Translation Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tungushpayev (2025) [2] | Explore ML/DL for ICU management and outcomes across diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. | P, D, M, T, I | Mixed | Multimodal (EHR, Imaging, Waveforms) | Internal, External/Temporal, Prospective/Impact | Yes |

| Koumantakis (2025) [13] | Systematically review and meta-analyze DL models for ICU readmission prediction and performance. | P, I | Adult ICU | EHR | Internal, External/Temporal, Unclear | Yes |

| Al-Jabri (2025) [14] | Review ICU delirium ML/DL prediction models, and assess performance, quality, and limitations. | P | Adult ICU | Multimodal (EHR, Waveforms) | Internal, External/Temporal, Prospective/Impact | Yes |

| Shi (2025) [15] | Evaluate AI-based AKI prediction in ICU, focusing on methods, data use, and applicability. | P | Adult ICU | EHR | Internal, External/Temporal | Yes |

| Berkhout (2025) [1] | Assess ICU AI operationalization over time, including TRL-based maturity and risk of bias. | I, P, D, T | Adult ICU | Multimodal (EHR, Imaging) | Internal, External/Temporal, Prospective/Impact | Yes |

| Rockenschaub (2025) [16] | Quantify external validation frequency for ML ICU scores and AUROC change on new hospitals. | P, I | Adult ICU | EHR | External/Temporal, Unclear | Yes |

| Tan (2025) [17] | Evaluate ML for early ARDS mortality prediction versus conventional scores and limitations. | P | Mixed | EHR | Internal, External/Temporal | Yes |

| Tudor (2025) [18] | Map NICU AI for outcome and length-of-stay prediction, including benefits and challenges. | P, I | NICU | Multimodal (EHR, Imaging) | Unclear | Yes |

| Millana (2025) [19] | Review AI in NICUs across prognosis, classification, monitoring, and forecasting, with integration issues. | P, D, M | NICU | Multimodal (Waveforms, Imaging, Other) | Unclear | Yes |

| Nikravangolsefid (2024) [20] | Synthesize sepsis ICU mortality ML models, including validation, calibration, and comparators. | P | Adult ICU | EHR | Internal, External/Temporal | Unclear |

| Schouten (2024) [21] | Assess maturity and risk of bias of AI models used during NICU/PICU stay. | P, D, M, T, I | NICU, PICU | Unclear | Internal, External/Temporal, Prospective/Impact, Real-world | Yes |

| Huerta (2024) [22] | Map CICU AI applications across key clinical workflows and use cases. | P, D, M, T, I | CICU | Multimodal (EHR, Imaging, Waveforms) | Unclear | Yes |

| Glaser (2024) [23] | Review ML for predicting and detecting new-onset atrial fibrillation in ICU. | P, D | Adult ICU | Multimodal (EHR, Waveforms) | External/Temporal | Yes |

| Frondelius (2024) [24] | Compare ML VAP prediction performance and assess interpretability, TRL, and risk of bias. | P, D | Adult ICU | Multimodal (EHR, Waveforms) | Internal, External/Temporal | Yes |

| Stubnya (2024) [25] | Summarize clinical evidence for ML prediction of sepsis-associated AKI in adult ICU sepsis. | P | Adult ICU | EHR | Internal, External/Temporal | Unclear |

| Yang (2023) [26] | Evaluate ML model performance for predicting sepsis onset. | P | Adult ICU, Other | EHR, Waveforms | Internal, External/Temporal | No |

| Rockenschaub (2023) [27] | Assess external validation frequency for ML ICU scores and performance in new hospitals. | P | Adult ICU | EHR | Internal, External/Temporal | Yes |

| Vagliano (2023) [28] | Critically appraise ICU mortality prognostic models using clinical note embeddings. | P | Adult ICU | EHR | Internal, External/Temporal | No |

| Moazemi (2023) [29] | Review AI for monitoring-focused clinical decision support in cardiovascular ICUs. | P, D, M, T, I | CICU | Multimodal (EHR, Waveforms) | Internal | Yes |

| Du (2023) [30] | Assess ML prediction of AKI risk among ICU patients. | P | Adult ICU | EHR | Internal, External/Temporal, Prospective/Impact | Yes |

| Adegboro (2022) [31] | Review neonatal and pediatric ICU AI for outcomes improvement and real-world readiness. | P, D, T, I | NICU, PICU | Multimodal (EHR, Waveforms, Imaging, Other) | Internal, External/Temporal, Prospective/Impact | Yes |

| van de Sande (2021) [4] | Assess ICU AI maturity, methods, risk of bias, clinical readiness, and trial outcomes. | P, D, I | Adult ICU | Multimodal (EHR, Waveforms, Imaging, Other) | Internal, External/Temporal, Prospective/Impact, Real-world | Yes |

| Moor (2021) [32] | Systematically review ML for sepsis onset prediction in adult ICU. | I, P, D | Adult ICU | Multimodal (EHR, Waveforms, Imaging, Other) | Internal, External/Temporal, Prospective/Impact, Real-world | Yes |

| Shillan (2019) [33] | Review ML on routinely collected ICU data by purpose, methods, validation, and accuracy. | P | Mixed | EHR | Internal, External/Temporal | Yes |

| Kwong (2019) [34] | Assess the effectiveness of ML for weaning in mechanically ventilated ICU patients. | I | Mixed | Multimodal (Waveforms, EHR) | Unclear | Yes |

| Barboi (2022) [35] | Meta-analyze ML versus severity scores for ICU mortality prediction and provide guidance. | P | Adult ICU | EHR | Internal, External/Temporal | Limited |

| Kamio (2017) [36] | Review ML for predicting clinical deterioration in critically ill patients, including utility. | P | Adult ICU | Multimodal (Waveforms, EHR) | Unclear | No |

| Malak (2019) [37] | Review AI techniques for NICU decision support across diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring. | P, D, M, T, I | NICU | Multimodal (EHR, Waveforms, Imaging) | Unclear | Yes |

| Musat (2024) [38] | Review ML models for mortality prediction in critically ill sepsis using routine EMR data. | P | Adult ICU | EHR | Internal, External/Temporal, Prospective/Impact | Yes |

| Syed (2021) [39] | Review ICU ML applications using the MIMIC dataset. | P, M | Adult ICU | Multimodal (EHR, Waveforms, Other) | Internal, Unclear | Yes |

| Khope (2023) [40] | Review MIMIC-III analytics and propose a predictive framework. | P, D | Adult ICU | EHR | Unclear | Limited |

| Gallifant (2022) [41] | Synthesize limitations and solutions for AI in mechanical ventilation, including TRIPOD and PROBAST. | P, D, I | Mixed | Multimodal (EHR, Waveforms) | Prospective/Impact, Internal, External/Temporal | Yes |

| Abdalwahab Abdallah (2025) [42] | Evaluate AI in PICUs for bias risk, adoption barriers, validation gaps, and readiness. | P, D, M, T, I | Mixed | Multimodal (EHR, Waveforms, Imaging, Other) | Unclear | Yes |

| Dhami (2025) [43] | Evaluate ICU in-hospital mortality AI/ML models versus traditional scoring systems. | P | Adult ICU | Multimodal (EHR, Waveforms, Imaging) | Internal, External/Temporal | Yes |

| Prognostic and Early Warning Models | Diagnostic and Detection Models | Monitoring and Dynamic Assessment Models | Treatment Support and Decision Support Models | Implementation and Readiness Focused Reviews | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n SR | 33 | 15 | 8 | 8 | 15 |

| Population (n SR): Adult ICU | 24 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Population (n SR): PICU | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Population (n SR): NICU | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Population (n SR): CICU | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Population (n SR): Other | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Population (n SR): Mixed | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Population (n SR): Unclear | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Modality (n SR): EHR | 31 | 13 | 6 | 7 | 14 |

| Modality (n SR): Waveforms | 17 | 12 | 7 | 6 | 10 |

| Modality (n SR): Imaging | 11 | 9 | 5 | 6 | 9 |

| Modality (n SR): Multimodal | 18 | 13 | 7 | 7 | 12 |

| Modality (n SR): Other | 6 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Validation (n SR): Internal | 28 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| Validation (n SR): External/Temporal | 26 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 11 |

| Validation (n SR): Prospective/Impact | 10 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Validation (n SR): Real-world | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Validation (n SR): Unclear | 10 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 7 |

| Prognostic and Early Warning Models | Diagnostic and Detection Models | Monitoring and Dynamic Assessment Models | Treatment Support and Decision Support Models | Implementation- and Readiness-Focused Reviews | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n SR | 33 | 15 | 8 | 8 | 15 |

| SR quality (n SR): High | 14 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| SR quality (n SR): Low | 19 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 10 |

| Clinical maturity | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Implementation maturity | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Validation (n SR): Internal | 28 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| Validation (n SR): External/Temporal | 26 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 11 |

| Validation (n SR): Prospective/Impact | 10 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Validation (n SR): Real-world | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Validation (n SR): Unclear | 10 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Żerdziński, K.; Janiec, J.; Jóźwik, K.; Łajczak, P.; Krzych, Ł.J. Artificial Intelligence in Intensive Care: An Overview of Systematic Reviews with Clinical Maturity and Readiness Mapping. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010185

Żerdziński K, Janiec J, Jóźwik K, Łajczak P, Krzych ŁJ. Artificial Intelligence in Intensive Care: An Overview of Systematic Reviews with Clinical Maturity and Readiness Mapping. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):185. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010185

Chicago/Turabian StyleŻerdziński, Krzysztof, Julita Janiec, Kamil Jóźwik, Paweł Łajczak, and Łukasz J. Krzych. 2026. "Artificial Intelligence in Intensive Care: An Overview of Systematic Reviews with Clinical Maturity and Readiness Mapping" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010185

APA StyleŻerdziński, K., Janiec, J., Jóźwik, K., Łajczak, P., & Krzych, Ł. J. (2026). Artificial Intelligence in Intensive Care: An Overview of Systematic Reviews with Clinical Maturity and Readiness Mapping. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010185