Impact of Prehabilitation Components on Oxygen Uptake of People Undergoing Major Abdominal and Cardiothoracic Surgery: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

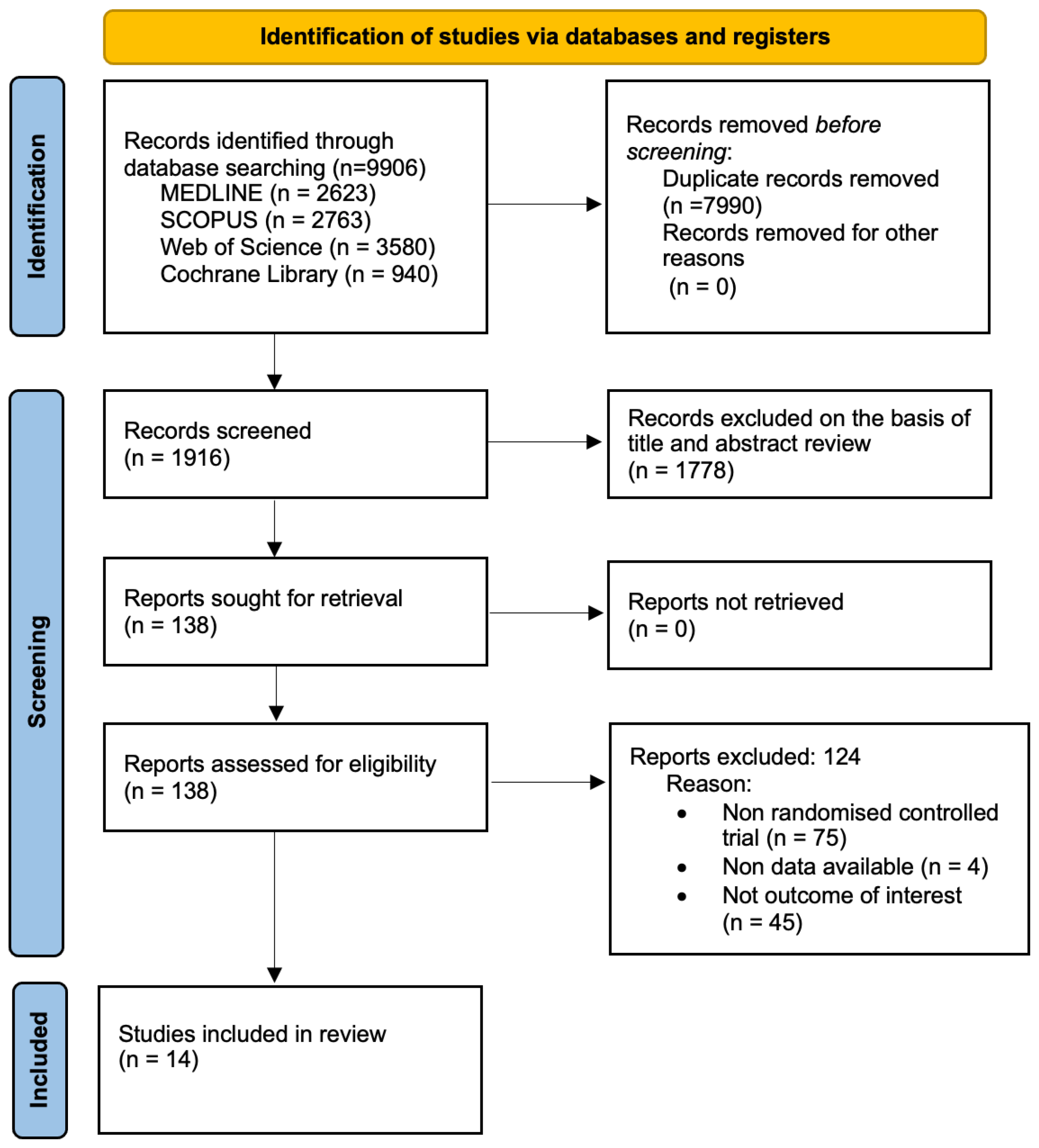

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

2.2. Eligibility

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Categorization of the Interventions

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Rating the Grade of Recommendations of the Evidence

2.7. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Risk of Bias

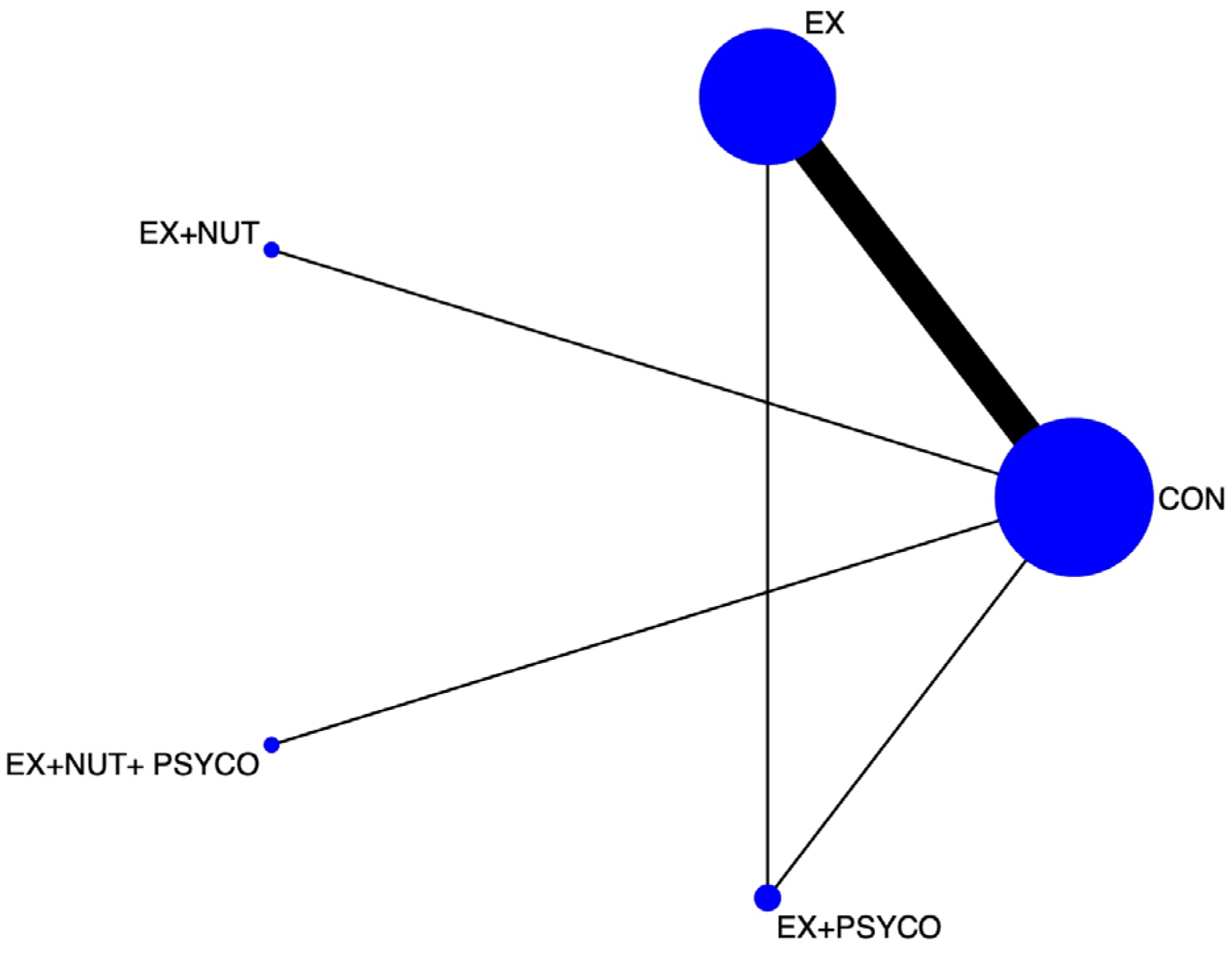

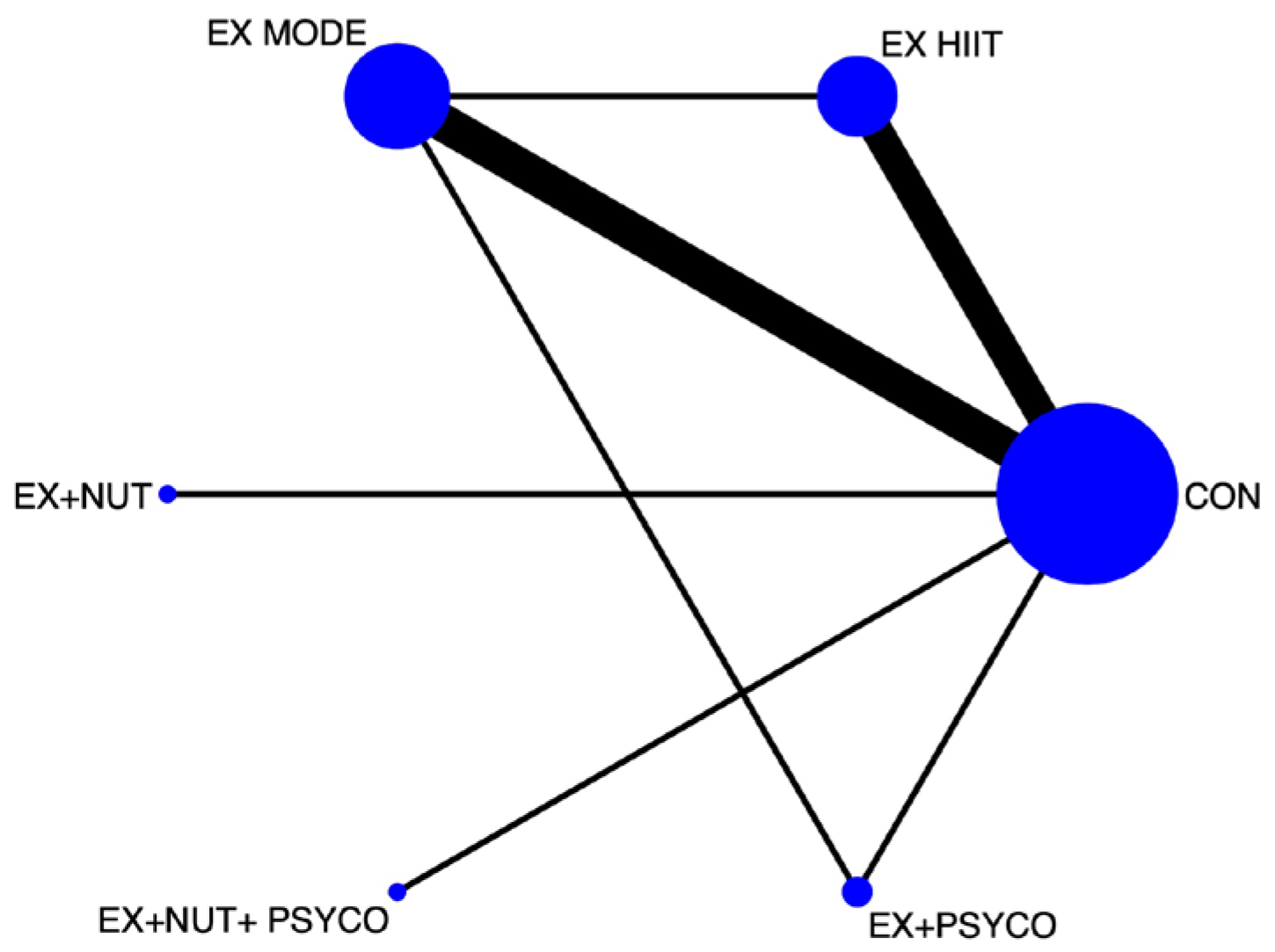

3.2. Network Meta-Analysis

3.3. Best Treatment Probabilities

3.4. Analysis of Sensitivity, Heterogeneity, and Publication Bias

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CEPT | Cardiopulmonary exercise test. |

| CRF | Cardiorespiratory physical fitness. |

| EX | Exercise. |

| HIIT | High-intensity interval training. |

| MODE | Moderate intensity. |

| NMA | Network meta-analysis. |

| NUT | Nutrition. |

| PA | Physical activity. |

| PSYCO | Psychological. |

| QoL | Quality of life. |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials. |

| VO2max | Maximal oxygen consumption. |

References

- Steffens, D.; Beckenkamp, P.R.; Young, J.; Solomon, M.; da Silva, T.M.; Hancock, M.J. Is preoperative physical activity level of patients undergoing cancer surgery associated with postoperative outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.H.A.; Kong, J.C.; Ismail, H.; Riedel, B.; Heriot, A. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Objective Assessment of Physical Fitness in Patients Undergoing Colorectal Cancer Surgery. Dis. Colon Rectum 2018, 61, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffens, D.; Ismail, H.; Denehy, L.; Beckenkamp, P.R.; Solomon, M.; Koh, C.; Bartyn, J.; Pillinger, N. Preoperative Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test Associated with Postoperative Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 7120–7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, J.K.; Baima, J. Cancer Prehabilitation: An opportunity to decrease treatment-related morbidity, increase cancer treatment options, and improve physical and psychological health outcomes. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 92, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, F.; Silver, J.K.; Feldman, L.S.; McKee, A.; Gilman, S.; Gillis, C.; Scheede-Bergdahl, C.; Gamsa, A.; Stout, N.; Hirsch, B. Surgical Prehabilitation in Patients with Cancer: State-of-the-science and recommendations for future research from a panel of subject matter experts. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. 2017, 28, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Qiu, T.; Pei, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Cui, Y.; Liang, N.; Li, S.; Chen, W.; Huang, Y. Two-Week Multimodal Prehabilitation Program Improves Perioperative Functional Capability in Patients Undergoing Thoracoscopic Lobectomy for Lung Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesth. Analg. 2019, 131, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnella, E.M.; Bousquet-Dion, G.; Awasthi, R.; Scheede-Bergdahl, C.; Carli, F. Multimodal prehabilitation improves functional capacity before and after colorectal surgery for cancer: A five-year research experience. Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnella, E.M.; Awasthi, R.; Loiselle, S.E.; Agnihotram, R.V.; Ferri, L.E.; Carli, F. Effect of Exercise and Nutrition Prehabilitation on Functional Capacity in Esophagogastric Cancer Surgery: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2018, 153, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, C.; Li, C.; Lee, L.; Awasthi, R.; Augustin, B.; Gamsa, A.; Liberman, A.S.; Stein, B.; Charlebois, P.; Feldman, L.S.; et al. Prehabilitation versus rehabilitation: A randomized control trial in patients undergoing colorectal resection for cancer. Anesthesiology 2014, 121, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, C.; Fenton, T.R.; Sajobi, T.T.; Minnella, E.M.; Awasthi, R.; Loiselle, S.; Liberman, A.S.; Stein, B.; Charlebois, P.; Carli, F. Trimodal prehabilitation for colorectal surgery attenuates post-surgical losses in lean body mass: A pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mina, D.S.; Hilton, W.J.; Matthew, A.G.; Awasthi, R.; Bousquet-Dion, G.; Alibhai, S.M.; Au, D.; Fleshner, N.E.; Finelli, A.; Clarke, H.; et al. Prehabilitation for radical prostatectomy: A multicentre randomized controlled trial. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 27, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindbäck, Y.; Tropp, H.; Enthoven, P.; Abbott, A.; Öberg, B. PREPARE: Presurgery physiotherapy for patients with degenerative lumbar spine disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Spine J. 2018, 18, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnella, E.M.; Awasthi, R.; Bousquet-Dion, G.; Ferreira, V.; Austin, B.; Audi, C.; Tanguay, S.; Aprikian, A.; Carli, F.; Kassouf, W. Multimodal Prehabilitation to Enhance Functional Capacity Following Radical Cystectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. Urol. Focus 2021, 7, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Rooijen, S.J.; Molenaar, C.J.; Schep, G.; van Lieshout, R.H.; Beijer, S.; Dubbers, R.; Rademakers, N.; Papen-Botterhuis, N.E.; van Kempen, S.; Carli, F.; et al. Making Patients Fit for Surgery: Introducing a four pillar multimodal prehabilitation program in colorectal cancer. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 98, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, C.; Buhler, K.; Bresee, L.; Carli, F.; Gramlich, L.; Culos-Reed, N.; Sajobi, T.T.; Fenton, T.R. Effects of Nutritional Prehabilitation, With and Without Exercise, on Outcomes of Patients Who Undergo Colorectal Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 391–410.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, D.F.J.; Jack, S.; Jones, R.P.; Jones, L.; Lythgoe, D.T.; Malik, H.Z.; Poston, G.J.; Palmer, D.H.; Fenwick, S.W. Randomized clinical trial of prehabilitation before planned liver resection. Br. J. Surg. 2016, 103, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, C.J.; Papen-Botterhuis, N.E.; Herrle, F.; Slooter, G.D. Prehabilitation, making patients fit for surgery–a new frontier in perioperative care. Innov. Surg. Sci. 2019, 4, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuri, S.F.; Henderson, W.G.; DePalma, R.G.; Mosca, C.; Healey, N.A.; Kumbhani, D.J. Determinants of Long-Term Survival After Major Surgery and the Adverse Effect of Postoperative Complications. Ann. Surg. 2005, 242, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.; Kehlet, H. Postoperative fatigue. World J. Surg. 1993, 17, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, J.; Wischmeyer, P.E.; Grocott, M.P.; Miller, T.E. Surgical Prehabilitation. Nutrition and exercise. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2018, 36, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitlinger, A.; Zafar, S.Y. Health-Related Quality of Life: The impact on morbidity and mortality. Surg. Oncol. Clin. 2018, 27, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boereboom, C.; Doleman, B.; Lund, J.N.; Williams, J.P. Systematic review of pre-operative exercise in colorectal cancer patients. Tech. Coloproctology 2016, 20, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, H.; Cormie, P.; Burbury, K.; Waterland, J.; Denehy, L.; Riedel, B. Prehabilitation Prior to Major Cancer Surgery: Training for Surgery to Optimize Physiologic Reserve to Reduce Postoperative Complications. Curr. Anesthesiol. Rep. 2018, 8, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; Blair, S.N.; Arena, R.; Church, T.S.; Despres, J.P.; Franklin, B.A.; Haskell, W.L.; Kaminsky, L.A.; Levine, B.D.; Lavie, C.J.; et al. Importance of Assessing Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Clinical Practice: A Case for Fitness as a Clinical Vital Sign: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016, 134, e653–e699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cupit-Link, M.C.; Kirkland, J.L.; Ness, K.K.; Armstrong, G.T.; Tchkonia, T.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Armenian, S.H.; Ruddy, K.J.; Hashmi, S.K. Biology of premature ageing in survivors of cancer. ESMO Open 2017, 2, e000250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.W.; Haykowsky, M.; Pituskin, E.N.; Jendzjowsky, N.G.; Tomczak, C.R.; Haennel, R.G.; Mackey, J.R. Cardiovascular Reserve and Risk Profile of Postmenopausal Women After Chemoendocrine Therapy for Hormone Receptor–Positive Operable Breast Cancer. Oncologist 2007, 12, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groarke, J.D.; Payne, D.L.; Claggett, B.; Mehra, M.R.; Gong, J.; Caron, J.; Mahmood, S.S.; Hainer, J.; Neilan, T.G.; Partridge, A.H.; et al. Association of post-diagnosis cardiorespiratory fitness with cause-specific mortality in cancer. Eur. Hearth J.-Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2020, 6, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.W.; Courneya, K.S.; Mackey, J.R.; Muss, H.B.; Pituskin, E.N.; Scott, J.M.; Hornsby, W.E.; Coan, A.D.; Herndon, J.E., II; Douglas, P.S.; et al. Cardiopulmonary Function and Age-Related Decline Across the Breast Cancer Survivorship Continuum. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2530–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S.H.; Wisløff, T.; Edvardsen, E.; Kollerud, S.T.; Jensen, J.S.; Agwu, G.; Matsoukas, K.; Scott, J.M.; Nilsen, T.S. Effects of Systemic Anticancer Treatment on Cardiorespiratory Fitness. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC: CardioOncology 2025, 7, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellissimo, M.P.; Canada, J.M.; Jordan, J.H.; Ladd, A.C.; Heiston, E.M.; Brubaker, P.; Mihalko, S.L.; Reding, K.; D’ Agostino, R., Jr.; O’ Connell, N.; et al. Changes in Physical Activity, Functional Capacity, and Cardiac Function during Breast Cancer Therapy. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2022, 31, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, A.B.; Thomas, S.M.; Dittus, K.; Jones, L.W.; Lakoski, S.G. Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Breast Cancer Patients: A Call for Normative Values. J. Am. Hearth Assoc. 2014, 3, e000432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutton, B.; Catalá-López, F.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement extension for systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analysis: PRISMA-NMA. Med. Clínica 2016, 147, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4 (Updated August 2023); Cochrane: London, UK, 2023; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A.D.; Akl, E.A.; Kunz, R.; Vist, G.; Brozek, J.; Norris, S.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Glasziou, P.; DeBeer, H.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, F.; Charlebois, P.; Stein, B.; Feldman, L.; Zavorsky, G.; Kim, D.J.; Scott, S.; Mayo, N.E. Randomized clinical trial of prehabilitation in colorectal surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2010, 97, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.K.; Brown, V.; White, D.; King, D.; Hunt, J.; Wainwright, J.; Emery, A.; Hodge, E.; Kehinde, A.; Prabhu, P.; et al. Multimodal Prehabilitation During Neoadjuvant Therapy Prior to Esophagogastric Cancer Resection: Effect on Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test Performance, Muscle Mass and Quality of Life—A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 29, 1839–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojesen, R.D.; Dalton, S.O.; Skou, S.T.; Jørgensen, L.B.; Walker, L.R.; Eriksen, J.R.; Grube, C.; Justesen, T.F.; Johansen, C.; Slooter, G.; et al. Preoperative multimodal prehabilitation before elective colorectal cancer surgery in patients with WHO performance status I or II: Randomized clinical trial. BJS Open 2023, 7, zrad134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Manley, K.; Shaw, B.; Lewis, L.; Cucato, G.; Mills, R.; Rochester, M.; Clark, A.; Saxton, J.M. Vigorous intensity aerobic interval exercise in bladder cancer patients prior to radical cystectomy: A feasibility randomised controlled trial. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 26, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Mayo, N.E.; Carli, F.; Montgomery, D.L.; Zavorsky, G.S. Responsive Measures to Prehabilitation in Patients Undergoing Bowel Resection Surgery. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2009, 217, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, C.; Bjarnason-Wehrens, B.; Baumgarten, H.; Walther, T.; Mengden, T.; Walther, C. Prehabilitation in patients awaiting elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery–effects on functional capacity and quality of life: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, 34, 1256–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tew, G.A.; Moss, J.; Crank, H.; Mitchell, P.A.; Nawaz, S. Endurance Exercise Training in Patients with Small Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93, 2148–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, H.M.; Shahin, Y.; Khan, J.A.; McCollum, P.T.; Chetter, I.C. Preoperative Supervised Exercise Improves Outcomes After Elective Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair. Ann. Surg. 2016, 264, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, M.; Loughney, L.; Lythgoe, D.; Barben, C.; Sripadam, R.; Kemp, G.; Grocott, M.; Jack, S. Effect of prehabilitation on objectively measured physical fitness after neoadjuvant treatment in preoperative rectal cancer patients: A blinded interventional pilot study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2015, 114, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dronkers, J.J.; Lamberts, H.; Reutelingsperger, I.M.M.D.; Naber, R.H.; Dronkers-Landman, C.M.; Veldman, A.; Van Meeteren, N.L.U. Preoperative therapeutic programme for elderly patients scheduled for elective abdominal oncological surgery: A randomized controlled pilot study. Clin. Rehabil. 2010, 24, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodfield, J.C.; Clifford, K.; Wilson, G.A.; Munro, F.; Baldi, J.C. Short-term high-intensity interval training improves fitness before surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2022, 32, 856–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, E.R.; Baglioni, S.; Bittencourt, L.; Lopes, C.L.N.; Neumann, C.R.; Trindade, M.R.M. What Is the Best Treatment before Bariatric Surgery? Exercise, Exercise and Group Therapy, or Conventional Waiting: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obes. Surg. 2016, 27, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, E.; O’Neill, L.M.; Kearney, N.; Sheill, G.; Brennan, L.; Wade, S. Preoperative exercise to improve fitness in patiens undergoing complex surgery for cancer of the lung or esophagus (PRE-HII). A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Surg. 2025, 282, 690–698. [Google Scholar]

- Ligibel, J.A.; Bohlke, K.; May, A.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Gilchrist, S.C.; Irwin, M.L.; Late, M.; Mansfield, S.; Marshall, T.F.; et al. Exercise, Diet, and Weight Management During Cancer Treatment: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2491–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.L.; Winters-Stone, K.M.; Wiskemann, J.; May, A.M.; Schwartz, A.L.; Courneya, K.S.; Zucker, D.S.; Matthews, C.E.; Ligibel, J.A.; Gerber, L.H.; et al. Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, S.C.; Barac, A.; Ades, P.A.; Alfano, C.M.; Franklin, B.A.; Jones, L.W.; La Gerche, A.; Ligibel, J.A.; Lopez, G.; Madan, K.; et al. Cardio-Oncology Rehabilitation to Manage Cardiovascular Outcomes in Cancer Patients and Survivors: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e997–e1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijwel, S.; Cardinale, D.A.; Norrbom, J.; Chapman, M.; Ivarsson, N.; Wengström, Y.; Sundberg, C.J.; Rundqvist, H. Exercise training during chemotherapy preserves skeletal muscle fiber area, capillarization, and mitochondrial content in patients with breast cancer. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 5495–5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagolin, M.; Trujillo, L.M.; Villanueva, S.; Ruiz, M.; VON Oetinger, A. Test cardiopulmonar: Una herramienta de utilidad diagnóstica y pronóstica. Rev. Medica De Chile 2020, 148, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, J.; Wilson, F.; Guinan, E.; McCormick, P.; Hussey, J.; Moriarty, J. The preoperative use of field tests of exercise tolerance to predict postoperative outcome in intra-abdominal surgery: A systematic review. J. Clin. Anesth. 2016, 35, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, D.A.; Uguccioni, G.; Vainshtein, A.; D’souza, D. Mechanisms of exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle: Implications for health and disease. Compr Physiol. 2011, 1, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priego-Jiménez, S.; Lucerón-Lucas-Torres, M.; Ruiz-Grao, M.C.; Guzmán-Pavón, M.J.; Lorenzo-García, P.; Araya-Quintanilla, F.; Álvarez-Bueno, C. Effect of exercise interventions on oxygen uptake in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 67, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handschin, C.; Spiegelman, B.M. The role of exercise and PGC1α in inflammation and chronic disease. Nature 2008, 454, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Millán, I. The Key Role of Mitochondrial Function in Health and Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, F.; Scheede-Bergdahl, C. Prehabilitation to Enhance Perioperative Care. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2015, 33, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.W.; Liang, Y.; Pituskin, E.N.; Battaglini, C.L.; Scott, J.M.; Hornsby, W.E.; Haykowsky, M. Effect of Exercise Training on Peak Oxygen Consumption in Patients with Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 2011, 16, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, C.P.; Prentis, J.F.; Jacques, B.F.; Anderson, H.F.; Manas, D.F.; Jones, D.; Trenell, M. Cardiorespiratory Fitness Predicts Mortality and Hospital Length of Stay After Major Elective Surgery in Older People. Ann. Surg. 2013, 257, 999–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Arias, F.L.; Sánchez-Guillén, L.; Ruiz, L.I.A.; Lara, C.D.; Gómez, F.J.L.; Pons, C.B.; Rodríguez, J.M.R.; Arroyo, A. Revisión narrativa de la prehabilitación en cirugía: Situación actual y perspectivas futuras. Cir. Esp. 2020, 98, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Characteristics | Population Characteristics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Country | N | Type of Surgery | Age (y), Mean ± SD or (CI) | Groups by Intervention | VO2 Peak Baseline (mL/min) | N Intervention |

| Carli et al., 2010 [36] | Canada | 112 | Colorectal | 61 ±16 | IG: EX | 1395 | 58 |

| 60 ± 15 | CG: CON | 1400 | 54 | ||||

| Allen et al., 2021 [37] | UK | 54 | Oesophagogastric cancer | 65 ±6 | IG: EX + NUT + PSYCO | 20.29 ± 4.25 | 26 |

| 62 ± 9 | CG: CON | 21.28 ± 3.58 | 28 | ||||

| Bojesen et al., 2023 [38] | Denmark | 36 | Colorectal cancer | 80 ± 6.9 | IG: EX + NUT | 12.6 ± 3.47 | 16 |

| 78 ± 6.3 | CG: CON | 12.5 ± 5.47 | 20 | ||||

| Banerjee et al., 2018 [39] | UK | 60 | Radical cystectomy | 71.60 ± 6.80 | IG: EX | 19.22 ± 4.80 | 30 |

| 72.50 ± 8.40 | CG: CON | 20.38 ± 5.59 | 30 | ||||

| Dunne et al., 2016 [16] | UK | 38 | Colorectal liver metastasis | 61 (56–66) | IG: EX | 17.6 ± 2.3 | 20 |

| 62 (53–722) | CG: CON | 18.6 ± 3.9 | 17 | ||||

| Kim et al., 2009 [40] | Canada | 21 | Major bowel resection; colorectal | 55 ± 15 | IG: EX | 21.5 ± 10.1 | 14 |

| 65 ± 9 | CG: CON | 20.3 ± 4.6 | 7 | ||||

| Steinmetz et al., 2020 [41] | Germany | 230 | Coronary artery bypass graft | 66.1 ± 9.0 | IG: EX | 15.7 ± 4.1 | 88 |

| 67.9 ± 7.9 | CG: CON | 16.2 ± 4.1 | 115 | ||||

| Tew et al., 2012 [42] | UK | 25 | Small abdominal aortic aneurysm | 71 ± 8 | IG: EX | 19.3 ± 4.5 | 11 |

| 74 ± 6 | CG: CON | 17.9 ± 5.4 | 14 | ||||

| Barakat et al., 2016 [43] | UK | 124 | Elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | 73.8 ± 6.5 | IG: EX | 18.4 ± 11.84 | 62 |

| 72.9 ± 7.9 | CG: CON | 19.6 ± 11.84 | 62 | ||||

| West et al., 2014 [44] | UK | 39 | Rectal cancer | 64 (45–82) | IG: EX | 16.0 ± 4.3 | 22 |

| 72 (62–84) | CG: CON | 15.7 ± 5.0 | 17 | ||||

| Dronkers et al., 2010 [45] | The Netherlands | 42 | Abdominal oncological | 71.1 ± 6.3 | IG: EX | 29.4 ± 9.5 | 22 |

| 68.8 ± 6.4 | CG: CON | 31.6 ± 6.5 | 20 | ||||

| Woodfield et al., 2022 [46] | New Zealand | 63 | Major abdominal | 66.5 ± 13.5 | IG: EX | 20.34 ± 5.211 | 28 |

| 66.0 ± 15.0 | CG: CON | 21.83 ± 6.45 | 35 | ||||

| Marcon et al., 2016 [47] | Brazil | 66 | Bariatric | 50.1 ± 2.8 | IG: EX+ PSYCO | 433.9 ± 16.8 | 17 |

| 43.4 ± 2.3 | IG: EX | 435 ± 15 | 22 | ||||

| 42.5 ± 2.7 | CG: CON | 427.2 ± 16 | 18 | ||||

| Smyth et al., 2025 [48] | Irland | 79 | Lung and oesophagus cancer | 62.07 ± 10.2 | IG: EX | 18.7 ± 5.0 | 42 |

| 65.24 ± 8.2 | IG: EX | 19.6 ± 5.4 | 37 | ||||

| Study | Groups by Intervention | Intervention | Time (min)/rep | Intensity | Duration (wk) | Frequency (x/wk) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carli et al., 2010 [36] | IG: EX CG: CON | EX: Bike + strengthening (push-ups, sit-ups, and standing strides). Walk/breathing: Subjects were encouraged to walk daily for a minimum of 30 min + breathing ex (DB at full vital capacity and diaphragmatic breathing, huffing and coughing) + exercise to activate circulation. | Bike: 20–30 min per day. Weight training: 12 rep. 10–15 min/day. Walk: 30 min. Breath: 5 min. Ex activate circulation: 5–10 min. | Bike: 50% MHR, was increased by 10% e/w. Weight training: The weight chosen was based on people who could lift to reach volitional fatigue with 8 rep. | 4 | Weight training: 3 3–5 Daily |

| Allen et al., 2021 [37] | IG: EX + NUT + PSYCO CG: CON | EX: Warm-up + CYC + RT (6 major muscle groups using free weights and resistance bands) + home exercise programme + patient diary) + activity monitor (Fitbit Flex2®). NUT: Individualized dietary goals. PSYCO: Six sessions of medical coaching. Usual care, and subjects were encouraged to remain active by undertaking regular aero ex (jogging/walk/CYC) + activity monitor (Fitbit Flex2®). | 1 h Warm-up: 5 min; CYC: 25 min; RT: 2 sets of 12 rep. | Warm-up: Very light intensity (9/20 Borg). CYC: 40–60% HRR (11–14/20 Borg) (fairly light to somewhat hard/hard). RT: 12–14 Borg (somewhat hard). | 15 | 2 supervised + 3 home ex PSYCO: 6 |

| Bojesen et al., 2023 [38] | IG: EX + NUT CG: CON | EX: HIIT (bike) + RT of large muscle groups. NUT: Consultation with a dietician + protein supplements + vitamins. Smoking cessation and possible drugs discontinuation or dose reduction. Standard care. | EX: HIIT: 4 HI bouts of 2–3 min, 3 min of low intensity. RT: 3 sets of 8–12 rep. NUT: 1 h consultation. | EX: HIIT: HI bouts at 90% of VO2 max low intensity at 30%. | 4 | EX: 3. NUT: twice/day. |

| Banerjee et al., 2023 [39] | IG: EX CG: CON | EX: Warm-up + CYC + cool-down. Standard care: Subjects were advised to carry on with their lifestyles in the ‘usual way’. | EX: 5–10 min warm-up + CYC (6 × 5 min intervals) + cool-down. | Warm-up (light RT: 50 W) + vigorous-intensity aero interval ex (HIIT) (13–15 Borg-70–85% predicted MHR based on 220-age) + active rest intervals (light RT: 50 W) + cool-down (low RT: 50 W). | 3–6 | 2 |

| Dunne et al., 2016 [16] | IG: EX CG: CON | Twelve interval ex sessions CYC (warm-up + interval training + warm-down). Standard care. | 30 min IT | HIIT: Mode (<60% VO2 peak) + vigorous (>90% VO2 peak). Based on baseline CPET. | 4 | 3 |

| Kim et al., 2009 [40] | IG: EX CG: CON | EX: Home-based programme. Aero: Subjects were given a portable cycle ergometer + recorded training in diaries. Basic instructions to prepare for surgery. | AERO: 40–65% HRR. | 4 | ||

| Steinmetz et al., 2020 [41] | IG: EX CG: CON | EX: Supervised and monitored cycle ergometer training. Two aero ex workouts with a 15 min phase of light gymnastics in between. Standard care. | EX: Two 10 min cycling workouts (1st session), gradually increased up to two 25 min cyc (6th session). | EX: 70% of VO2peak. | 2 | Aero: 3. |

| Tew et al., 2012 [42] | IG: EX CG: CON | EX: Each session involved a mixture of treadmill walking and CYC. Standard care. | EX: 35–45 min. | EX: 12–14 Borg (6–20 scale). | 12 | 3 |

| Barakat et al., 2016 [43] | IG: EX CG: CON | EX: Warm-up + ST + CYC + RT (heel-raise, knee extensions, dumbbells, biceps/arm curls rep, step-up lunges, knee bends) + cool-down + ST. Standard care: Continue with their normal lifestyle. | EX: 1 h. 5 min warm-up + 2 min e/e RT. | EX: Mode intensity. | 6 | 3 |

| West et al., 2014 [44] | IG: EX CG: CON | EX: Warm-up + cool-down + HIIT Standard care. | 40 min. 5 min warm-up + 5 min cool-down. | HIIT: First sessions: 4 by 3 min interval at 80% WR at VO2 AT (mode intensity) + 4 by 2 min interval at 50% WR at VO2. between peak and AT (severe intensity). Increased to 40 min (6 × 3 intervals at mode intensity + 6 × 2 intervals at severe intensity). | 6 | 3 |

| Dronkers et al., 2010 [45] | IG: EX CG: CON | EX: Warm-up + RT (lower limb extensors) + IMT + aero + training functional activities + cool-down + walking or CYC for a minimum of 30 min/day + DB + diaphragmatic breathing + incentive spirometry and coughing and forced expiration techniques. Standard care: Home-based exercise advice; subjects were encouraged to be active for a minimum of 30 min/day + pedometer + DB + diaphragmatic breathing + incentive spirometry and coughing and forced expiration techniques. | 60 min: 5 min warm-up + RT (1 set of 8–15 rep) + 15 min IMT + 20–30 min aero. | RT: 60–80% 1RM. IMT: 10–60% PIM. Aero: Mode intensity (55–75% MHR- 11–13 Borg). | 2–4 | 2 |

| Woodfield et al., 2022 [46] | IG: EX CG: CON | Warm-up + CYC + cool-down + lifestyle habits. Standard care + lifestyle habits. | 30 min CYC: 5 min warm-up + 20 min + HIIT + 5 min cool-down. 5 2 min intervals followed by 1–2 min of lower intensity. | HIIT: 90% MHR + low/mode intensity. 1 min interval of HI (aim of reaching 90% MHR at least once during session) + 1 min active rest (60% MHR). 6–20 Borg. | 4 | |

| Marcon et al., 2016 [47] | IG: EX + PSYCO IG: EX CG: CON | EX: Aero + ST + subjects were encouraged to increase number of steps daily. PSYCO: Sessions conducted by a psychologist with strategies based on promoting and maintaining new healthy behaviours, as well as reducing undesirable behaviours (sedentary lifestyle, increased food intake, and overconsumption of carbohydrates and fat). EX: Aero + ST + subjects were encouraged to increase number of steps daily. Standard care. | EX: 25 min + 5 min ST. PSYCO: 1 h. | Borg scale: 2–4 low-to-moderate intensity. | EX: 2 PSYCO: 1 EX: 2 | |

| Smyth et al., 2025 [48] | IG: EX IG: EX | EX HIIT: Physiotherapist-supervised HIIT programme + standard preoperative care. EX MODE: Mode intensity aero ex + 3–5 ST ex targeting major muscle groups + standard preoperative care. | CYC: 5 min warm-up (50% Wpeak) + 30 min of 15 sec intervals (100% Wpeak/0 watts) + 3 min cool-down (30 watts). 20 min mode intensity. | Min 2 | 5 2 first weeks 3 After 2 weeks 2 in person +3 online |

| CONTROL | 0.25 (0.06; 0.45) | −0.01 (−0.66; 0.65) | 0.09 (−0.44; 0.63) | 0.75 (0.06; 1.43) |

| 0.44 (0.11; 0.78) | EX | NA | NA | 0.60 (−0.05; 1.25) |

| 0.06 (−1.17; 1.28) | −0.39 (−1.66; 0.88) | EX + NUT | NA | NA |

| 0.24 (−0.86; 1.34) | −0.21 (−1.36; 0.94) | 0.18 (−1.46; 1.83) | EX + NUT + PSYCO | NA |

| 0.33 (−0.56; 1.22) | −0.11 (−1.01; 0.78) | 0.27 (−1.24; 1.79) | 0.09 (−1.32; 1.51) | EX + PSYCO |

| CONTROL | 0.22 (0.02; 0.41) | 0.26 (−0.11; 0.63) | −0.01 (−0.66; 0.65) | 0.09 (−0.44; 0.63) | 0.75 (0.06; 1.43) |

| 0.51 (0.04; 0.97) | EX HIIT | 0.32 (−0.12; 0.77) | NA | NA | NA |

| 0.40 (−0.04; 0.84) | −0.11 (−0.69; 0.47) | EX MODE | NA | NA | 0.60 (−0.05; 1.25) |

| 0.06 (−1.21; 1.33) | −0.45 (−1.80; 0.90) | −0.34 (−1.69; 1.00) | EX + NUT | NA | NA |

| 0.24 (−0.91; 1.39) | −0.27 (−1.51; 0.97) | −0.16 (−1.39; 1.07) | 0.18 (−1.53; 1.89) | EX + NUT + PSYCO | NA |

| 0.31 (−0.63; 1.24) | −0.20 (−1.22; 0.83) | −0.09 (−1.03; 0.84) | 0.25 (−1.33; 1.83) | 0.25 (−1.33; 1.83) | EX + PSYCO |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Priego-Jiménez, S.; Priego-Jiménez, P.; López-González, M.; Martinez-Rodrigo, A.; López-Requena, A.; Álvarez-Bueno, C. Impact of Prehabilitation Components on Oxygen Uptake of People Undergoing Major Abdominal and Cardiothoracic Surgery: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010175

Priego-Jiménez S, Priego-Jiménez P, López-González M, Martinez-Rodrigo A, López-Requena A, Álvarez-Bueno C. Impact of Prehabilitation Components on Oxygen Uptake of People Undergoing Major Abdominal and Cardiothoracic Surgery: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010175

Chicago/Turabian StylePriego-Jiménez, Susana, Pablo Priego-Jiménez, María López-González, Arturo Martinez-Rodrigo, Anais López-Requena, and Celia Álvarez-Bueno. 2026. "Impact of Prehabilitation Components on Oxygen Uptake of People Undergoing Major Abdominal and Cardiothoracic Surgery: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010175

APA StylePriego-Jiménez, S., Priego-Jiménez, P., López-González, M., Martinez-Rodrigo, A., López-Requena, A., & Álvarez-Bueno, C. (2026). Impact of Prehabilitation Components on Oxygen Uptake of People Undergoing Major Abdominal and Cardiothoracic Surgery: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010175