1. Introduction

Sudden cardiac arrest affects around 30,000 people every year in the UK. Of the 8–10% of patients who survive this event, around 70% experience fatigue, half have some degree of cognitive impairment and between 1/4 and 1/3 experience significant symptoms of low mood, anxiety and/or post-traumatic stress disorder six months after the event [

1]. Recent guidelines [

1] position statements [

2,

3] and quality standards [

4] recommend the investigation of all these domains, before and after discharge. To date, however, no study has been published on the implementation of these guidelines in routine clinical practice.

Guidance on how to complete the screening is scant. European Resuscitation Council guidelines recommend performing “functional assessments of physical and non-physical impairment” before discharge from hospital: this refers to a wide range of (semi)structured evaluations aimed at understanding the patient’s current capabilities and limitations, and to inform rehabilitation, discharge planning, and ongoing care. Their use has been relatively limited in published studies, with a few exception—namely, the Frenchay Activities Index (FI) [

5], the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living [

6], the assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) and the Activities of Daily Living Interview (ADL-I) [

7,

8] which, however, are unlikely to be widely used in routine clinical practice where the assessment of ADLs is more often unstandardised, variable and informal.

ERC guidelines recommend using the MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) to formally evaluate cognition, and the IQCODE-CA (Informant Questionnaire of Cognitive decline in the Elderly—Cardiac Arrest version) and the CLCH-24 (Checklist Cognition and Emotion) to investigate informants’ and patients’ insight into cognition and behaviour, respectively, if required.

The HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) is also recommended for the screening of emotional problems and widely available. No specifically validated tool is recommended to assess fatigue, despite this being the most common complaint, with only a handful of tools having been used in the literature (Modified Fatigue Impact Scale; Fatigue Severity Scale; Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System-Fatigue Scale; Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20) [

9,

10,

11]).

In this context, working practices in the use of screening tools for cognition, mood and fatigue are largely understudied in the UK; unsurprisingly, no information is currently available on what tools are being used in different cardiac arrest centres (as defined in [

12]) to screen survivors following an OHCA, their acceptability to patients and what type of barriers and facilitators can affect their routine use.

In this audit, we operationalised the 2021 ERC–ESICM post-resuscitation guidelines into five criteria and prospectively audited adherence across four centres in South-East England. The 2025 guidelines update preserves the same core elements (functional assessment before discharge; organised ≤3-month follow-up with cognitive, emotional, and fatigue screening; information/support for patients and co-survivors [

13], so our endpoints remain aligned; the added emphasis on structured rehabilitation does not change them.

2. Methods

2.1. Structure of the Clinical Audit

2.1.1. Participating Organizations and Timeframe of Audit

A multidisciplinary working group on ‘care and rehabilitation’ following OHCA first met in December 2022, comprising therapists from 4 different NHS Hospital Trusts in Southeast/Eastern England (King’s College Hospital, NHS Foundation Trust; Barts Health NHS Trust; Mid and South Essex NHS Foundation Trust; Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust). These specialized tertiary hospital units serve a large catchment area across London, Essex and Norfolk, covering a population of around 6.2 million people, and at the time had established pilot systems to complete pre-discharge and follow-up assessments for OHCA survivors (

Figure 1).

To gain some system-level insights into the way these systems were structured and implemented, the group decided to engage in a prospective, multi-centre, 6-month audit of current practices in the assessment of cognition, mood, fatigue, and quality of life following an OHCA.

The audit was divided into pre-discharge and follow-up sections. All patients admitted between the 1 June 2023 and the 30 November 2023 who were discharged alive from hospital were included in the audit; the follow-up section of the audit was completed when the last patient recruited was seen at follow-up.

2.1.2. Data Collection Methods and Tools Used

A single audit proforma and accompanying guidance document were developed by a multidisciplinary working group, based on the 2021 ERC post-resuscitation care guidelines. At each site, a designated clinical lead (specialist occupational therapist or clinical psychologist) extracted data from electronic health records and local cardiac arrest databases into the shared proforma (

Supplementary Material S1). Operational definitions of pre- and post-discharge criteria were specified for each item (see Audit Criteria and Standards Used

Section 2.1.3). The coordinating centre provided clarification as needed via email and online meetings. The final anonymised dataset was collated centrally and subjected to range and logic checks (e.g., consistency between discharge status and follow-up entries, plausible date sequences); any discrepancies were resolved by re-checking source records at the relevant site. Details of specific cognitive assessments and questionnaires used in each centre are provided in

Supplementary Material S2.

2.1.3. Audit Criteria and Standards Used

This audit assessed the compliance with European Resuscitation Council guidelines on post-resuscitation care. Two standards were specifically investigated:

Standard 1—pre-discharge care “Providing information and performing functional assessments of physical and non-physical impairments before discharge from the hospital”.

Standard 2—post-discharge care “

Systematic follow-up of all cardiac arrest survivors within 3 months following hospital discharge, which should, at least, include cognitive screening, screening for emotional problems and fatigue, and the provision of information and support for patients and their family”. Based on these standards, we derived and operationalised five audit criteria with explicit definitions and denominators to ensure reproducible coding (

Table 1).

For the purpose of this audit, a pre-discharge ‘functional assessment’ was defined as a structured or semi-structured, performance-based evaluation of everyday activities, capturing both physical functioning and functional cognition—that is, how cognitive skills are applied to real-world tasks. It was coded as completed if, before discharge, the patient underwent at least one functional assessment listed in the proforma (e.g., Multiple Errands Test, PADL assessment, etc.) and this was documented in the medical record. Isolated cognitive screening (e.g., MoCA, ACE-III, FreeCog), general mobility grading (e.g., transfers or walking with/without aids), narrative observations from ward staff, and patient self-report of independence did not fulfil this criterion. Provision of information was defined as documented provision of written or verbal information about cognitive, emotional, and fatigue sequelae.

2.1.4. Identification and Coding of Barriers and Facilitators

For each audit criterion, local leads categorised reasons for non-completion using a list of predefined options (e.g., patient fatigue, competing clinical priorities, lack of staff time, perceived lack of necessity) and provided free-text comments where needed. These reasons were then mapped to the 14-domain Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) by a clinical psychologist (MM) with experience in behaviour change and implementation science, to help identify mechanisms of change within complex healthcare settings [

14].

Coding was reviewed and refined in team meetings, and any uncertainties resolved by consensus. When a barrier clearly spanned more than one TDF domain, the domain judged most salient was selected as the primary code.

2.1.5. Ethics

According to guidance published by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, this project was classified as a clinical audit and registered at MSE (Mid and South Essex NHS Trust) with reference number CTCCA103 in October 2023. No ethics application was required as patients continued to receive standard clinical care without any modification or intervention beyond routine practice.

2.1.6. Data Analysis and Interpretation

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize patient demographics, clinical features, and the frequency of assessments completed pre-discharge and during follow-up. Continuous variables (e.g., age, length of hospital stay, days from hospital discharge to follow-up) were summarized using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), reflecting the non-normal distribution typically seen in clinical audit data. Categorical variables (e.g., sex, location of arrest, presenting rhythm) were summarized using frequencies and percentages.

Compliance with the predefined audit criteria was calculated and expressed as percentages to illustrate performance against standards. Analysis of assessment completion rates distinguished between pre-discharge and post-discharge phases, with additional stratification by assessment type (cognitive screening, emotional problems, fatigue).

Comparative analyses between centres were not performed as the audit’s main objective was to highlight practice variations collectively and generate shared learning rather than evaluate individual centre performance.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 29.0.1.

3. Results

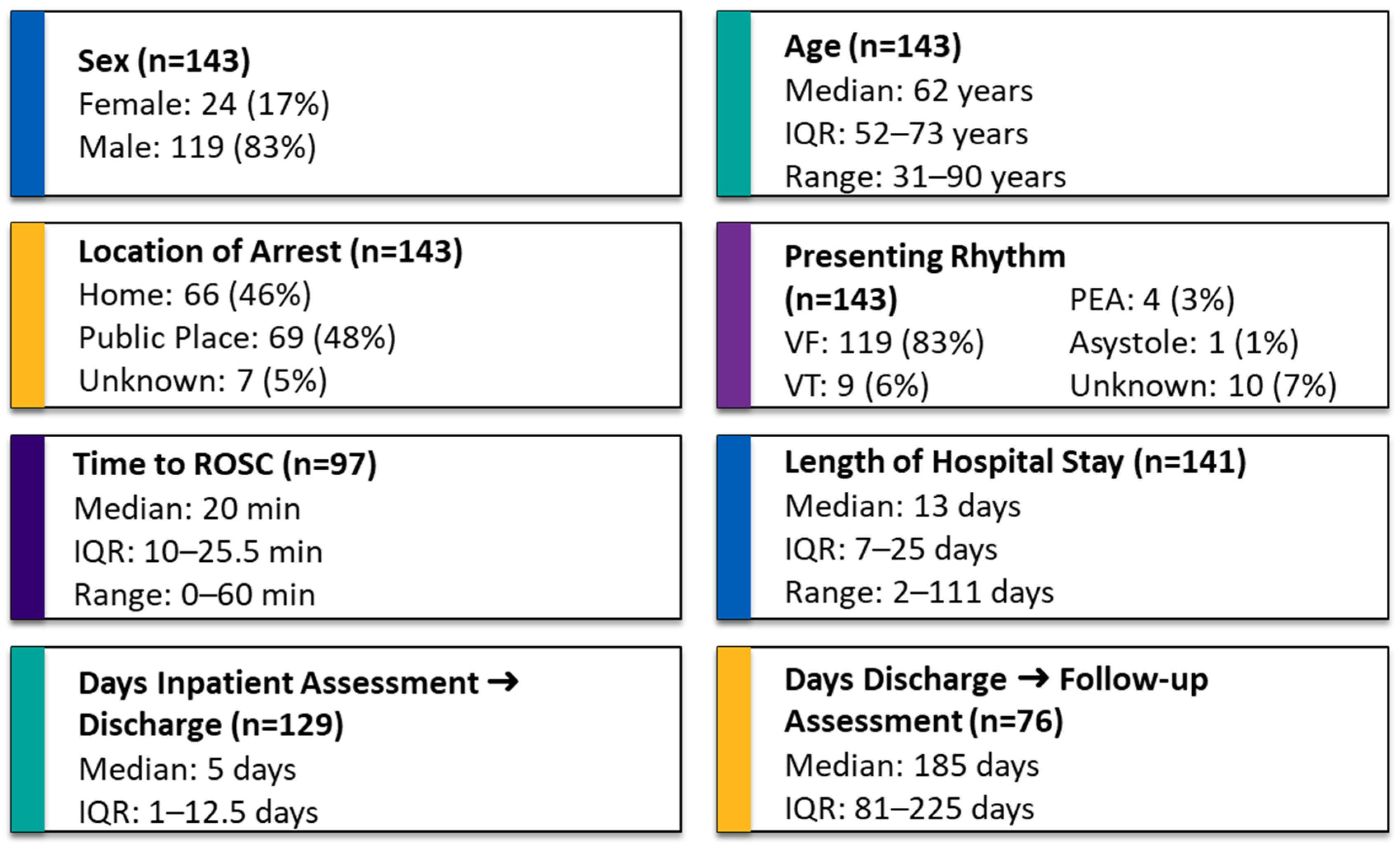

A total of 143 OHCA patients were discharged alive from hospital across the 4 sites during the 6 months of this audit. Descriptive variables are presented in

Figure 2. Normality testing using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicated that time to ROSC, length of hospital stay, days from inpatient assessment to hospital discharge, and days from hospital discharge to follow-up were not normally distributed (

p < 0.001), whereas the assumption of normality could not be rejected for age (

p = 0.2) (

Figure 2).

Adherence to pre-discharge criteria (Criterion A) was assessed in the full cohort (N = 143), while adherence to follow-up content criteria (Criterion B–E) was assessed among those who attended follow-up (N = 87).

Pre-discharge functional assessments meeting our operational definition were completed for 81/143 patients (56%). In a further 35 cases, an assessment was attempted but not completed because patients declined (

n = 3), were discharged before the assessment could be administered (

n = 12), the assessment was initiated but not finished (

n = 5), or they were unable to participate due to severe disability (modified Rankin Scale > 3;

n = 15). In 27 cases, clinicians did not administer a performance-based functional assessment as defined in

Table 1.

For follow-up, the audit tracked provision of information and support. Of the 143 patients discharged alive, 11 died before follow-up, 24 were not invited because of local policies (discharged out of area, not admitted to ICU), and 21 had follow-up arranged but not completed (non-attendance or no contact). The remaining 87 (61%) attended at least one structured follow-up. Complete discharge and follow-up dates were available for 76/87 patients—unfortunately, a system-wide change in electronic records in one of the sites in October 2023 led to missing follow-up date entries for 11 patients. Among the 76 with confirmed dates, only 19 (25%) were seen within the recommended three months, with a median follow-up time of 185 days [IQR 81–225] [

Figure 3].

Regarding follow-up content, cognitive screening was completed in 44%, screening for emotional problems in 52%, and fatigue assessment in 51%. The most common reason for omission was patients declining standardised assessments after reporting no problems; other reasons were clinician discretion, time constraints, or severe cognitive impairment [

Figure 4; panel 3B]. A family member was invited in all cases, but only 39/87 (45%) attended.

4. Discussion

In this prospective audit we investigated compliance with post-resuscitation ERC guidelines across four tertiary cardiac arrest centres in the southeast of England that were, at the time, providing both in-patient and follow-up care. Guidelines were operationalised into five measurable criteria, and compliance was evaluated by collecting additional information on implementation barriers when a standard could not be followed or was not adhered to. We also reported the percentages of assessments attempted but ultimately unsuccessful, with a view to providing insights into real-life implementation challenges. An infographic overview of these criteria, care pathways and observed implementation gaps is provided in

Figure 4. In this discussion, we classify barriers using the Theoretical Domains Framework—an established taxonomy in implementation research that helps identify reasons why things do not happen in practice.

4.1. Pre-Discharge Care

In terms of pre-discharge care, the discrepancy between completed and offered assessments was due mainly to four factors: patients’ level of cognitive impairment, patients declining the assessment, clinicians not having enough time to complete them, and assessments not being offered as existing information was considered sufficient.

In this cohort, a poor neurological outcome was relatively uncommon—only 15/143 (9.5%) of patients showed marked neurological impairment; this is in line with data from Western countries, where withdrawal of life sustaining treatment is routinely practiced [

15]. Nonetheless, this subgroup has highly complex rehabilitation and information needs that are best met by access to specialist neurorehabilitation services, as advocated in the NICE Guideline NG211 (“Rehabilitation after traumatic injury”) and the Royal College of Physicians guideline on prolonged disorders of consciousness. In the larger group of survivors with less significant neurological and cognitive problems, the second, third and fourth factor can be mapped, respectively, to the “Beliefs about consequences (patient-related)”, “Environmental context and resources” and “Beliefs about consequences (clinician-related)” TDF domain. Whilst the former was a minor barrier in this audit, the second affected a larger proportion of patients. Suggested mitigation measures include adding a checklist item to the discharge summary, flagging patients at risk of being discharged early, and/or increasing capacity in the system by providing additional administration or clinician time (

Table 2).

In cases coded as ‘not offered’, free-text comments and discussions with participating teams suggested that this label was often used when acute time pressures coincided with reassuring information from standardised cognitive tests, mobility assessments and ward observations, and an additional functional assessment was judged unlikely to change management for that admission. Embedding functional assessments within local standard operating procedures and protecting sufficient clinical time and staffing to complete them may therefore be key to ensuring they are used consistently, particularly given their potential to uncover higher-level difficulties that may be missed by standardised tests alone.

4.2. Post-Discharge Care

Inconsistent provision of follow-up care was due to several factors, largely mapping to three TDF domains—namely “Environmental context and resources”, “Beliefs about consequences/motivation (patient-related)” and “Social Influences”.

From an environmental perspective, local organisational policies played a central role. At several sites, operational procedures did not mandate follow-up for patients not admitted to ICU or discharged outside the hospital’s catchment area. As a result, many survivors were never offered a follow-up appointment. Even among those who were invited, specific assessments were sometimes omitted because they were not embedded in the routine follow-up workflow and remained discretionary (e.g., 15, 8 and 4 patients not offered cognitive, mood and fatigue assessments, respectively). Limited clinic time further restricted delivery (6, 5 and 4 patients where cognitive, mood and fatigue assessments were planned but not completed). Overall capacity constraints were also reflected in timing: only one quarter of patients with complete data were seen within the recommended 90 days, with a median follow-up around six months after discharge. Patient-related beliefs and motivation also appeared influential. Among those offered an appointment, around one fifth did not attend or could not be contacted, and among attendees a sizeable minority declined individual components of the assessment (standardised cognitive assessment, mood or fatigue screening). This suggests that some survivors either did not perceive a likely benefit from further assessment or were reluctant to take on additional healthcare burden. However, such decisions are unlikely to be purely individual: cultural norms, stigma, language barriers, family support and practical or financial constraints may all influence whether patients engage with follow-up, mapping onto the “Social influences” domain. Similar factors probably contributed to the relatively low attendance of relatives: although family members were invited for all patients seen in clinic (N = 87), fewer than half (39; 45%) attended, and none of the centres had procedures for actively involving relatives when the patient themselves declined or could not be reached. Another important consideration, although not directly captured in our audit data, is that many survivors already have scheduled contact with cardiology services for secondary prevention (for example, PCI follow-up, ICD clinics and cardiac rehabilitation programmes). At present, these pathways often run in parallel to survivorship assessments, representing a missed opportunity. Future service development and audit work should therefore explore better integration between survivorship pathways and these established secondary-prevention clinics, so that organisational policies and follow-up structures facilitate post–cardiac arrest care.

5. Limitations

This audit has several limitations. First, it was observational and non-comparative in design. While it allowed for the prospective collection of implementation data across multiple centres, it did not aim to evaluate the effectiveness of specific interventions, compare performance between sites, or assess clinical outcomes. As such, findings should be interpreted as descriptive of current practice rather than indicative of impact.

Second, the lack of standardisation across centres limited internal consistency. Variations in how assessments were administered, documented, or prioritised reflected local resource constraints and existing workflows, making direct comparisons between sites inappropriate. This heterogeneity is informative but constrains generalisability.

Third, selection bias may have influenced follow-up data. Although 132 patients were eligible for follow-up, only 108 were invited, with some patients excluded due to local referral procedures—for example, those not admitted to ICU or discharged outside a hospital’s catchment area. This may have skewed findings toward those more likely to engage with services.

Fourth, while the audit captured which tools were used, it did not assess how consistently or accurately they were applied, or whether staff received training. The psychometric robustness of these tools in this context was also not examined, and some are not specifically recommended for OHCA survivors.

Finally, the audit did not include any formal measures of acceptability, burden, or perceived utility of assessments from the perspectives of patients, relatives, or clinicians. These insights are critical for guiding meaningful quality improvement and ensuring that interventions are not only deliverable but valued by those involved.

In addition, this audit was conducted at four large hospital trusts that already had infrastructure in place to offer post-resuscitation follow-up care and had expressed an interest in improving practice. As such, these centres likely represent a best-case scenario within the wider system. The level of care delivered across all trusts nationally—many of which may lack structured follow-up pathways or access to rehabilitation staff—is likely to be lower. This selection bias should be considered when interpreting the findings and planning for wider implementation.

6. Conclusions

This multicentre prospective audit provides insights into the current implementation of post-resuscitation ERC guidelines across four specialist centres in southeast England. By operationalising guidelines into measurable criteria, we identified specific areas of incomplete adherence and, crucially, barriers mapped to the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF).

Barriers related to Environmental context and resources were particularly prominent, notably affecting timely assessments both pre-discharge and during follow-up. Limited staff availability, short hospital stays and fragmented or inconsistent follow-up procedures indicate the need for organisational strategies such as standardising assessment workflows, clarifying responsibilities, embedding assessment tasks into routine discharge summaries, and ensuring sufficient clinical and administrative capacity.

Patient-related factors mapped onto the domain of Beliefs about consequences, also significantly influenced guideline adherence. Patients and relatives frequently declined or did not engage with offered assessments, highlighting a need for approaches that enhance their understanding of the value of follow-up and reduce perceived burden, such as framing assessments as routine care, providing early informational interventions, or offering flexible attendance formats (e.g., telehealth options).

Future improvement efforts should leverage these TDF insights, prioritizing interventions that directly target the identified behavioural domains. This could include operational changes (e.g., protected time for follow-up assessments, integration with established secondary-prevention clinics), targeted training and education programs to shift clinician perceptions and behaviours, and improved patient and relative communication strategies [

Supplementary Material S3]. Adopting a structured, theory-informed approach offers the greatest potential to enhance guideline adherence, ensuring comprehensive, equitable, and sustainable rehabilitation care following cardiac arrest.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm15010174/s1. Supplementary Materials S1: List of cognitive assessments/mood screen questionnaires in use at the time of the Audit in the 4 hospital Trusts; Supplementary Materials S2: Audit data collection template (In-Hospital and Follow-Up); Supplementary Materials S3: Infographic showing where and why guideline-recommended assessments were not delivered across the OHCA pathway, grouping barriers by stage and TDF domain and linking them to service-, clinician- and patient/family-level solutions (colours denote TDF domains).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization (idea formulation), M.M.; methodology (study design and audit framework), M.M., A.S., M.K., C.K. and S.M.; validation (cross-checking and verification of data and interpretations), M.M.; formal analysis (data processing and summary statistics), M.M.; investigation (data collection and site coordination), M.K., A.S., S.M., J.D., U.S. and C.K.; data curation (data entry and quality control), M.M. and C.K.; writing—original draft preparation (manuscript drafting), M.M.; writing—review and editing (critical revision and approval of the final text), M.K., A.S., C.K., N.G., N.P. and T.R.K.; visualization (figure design and layout), M.M.; supervision (oversight and guidance), T.R.K. and N.G.; project administration (coordination across sites), M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and registered as a clinical audit at Mid and South Essex NHS Foundation Trust (reference number CTCCA103, 24 October 2023). Ethical approval was not required as the project met criteria for clinical audit under the UK Health Research Authority and Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership guidance.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study involved analysis of anonymised audit data and did not include identifiable human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The aggregated, anonymised audit dataset underlying this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and subject to local information governance approvals. No publicly archived datasets were generated.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all clinicians and therapists across the participating centres for their invaluable support in data collection and local audit registration. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI) to assist with language editing and structural refinement and Gemini 3.0 (Google) for producing the infographics. The authors have reviewed and edited all AI-generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Nolan, J.P.; Sandroni, C.; Böttiger, B.W.; Cariou, A.; Cronberg, T.; Friberg, H.; Genbrugge, C.; Haywood, K.; Lilja, G.; Moulaert, V.R.M.; et al. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Guidelines 2021: Post-Resuscitation Care. Resuscitation 2021, 161, 220–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, K.N.; Camp-Rogers, T.R.; Kotini-Shah, P.; Del Rios, M.; Gossip, M.R.; Moitra, V.K.; Haywood, K.L.; Dougherty, C.M.; Lubitz, S.A.; Rabinstein, A.A.; et al. Sudden Cardiac Arrest Survivorship: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, E654–E685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mion, M.; Simpson, R.; Johnson, T.; Oriolo, V.; Gudde, E.; Rees, P.; Quinn, T.; Von Vopelius-Feldt, J.; Gallagher, S.; Mozid, A.; et al. British Cardiovascular Intervention Society Consensus Position Statement on Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest 2: Post-Discharge Rehabilitation. Interv. Cardiol. Rev. Res. Resour. 2022, 17, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resuscitation Council UK. Quality Standards: Survivors; Resuscitation Council UK: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.resus.org.uk/library/quality-standards-cpr/quality-standards-survivors (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Moulaert, V.R.M.P.; Wachelder, E.M.; Verbunt, J.A.; Wade, D.T.; Van Heugten, C.M. Determinants of Quality of Life in Survivors of Cardiac Arrest. J. Rehabil. Med. 2010, 42, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geri, G.; Dumas, F.; Bonnetain, F.; Bougouin, W.; Champigneulle, B.; Arnaout, M.; Carli, P.; Marijon, E.; Varenne, O.; Mira, J.P.; et al. Predictors of Long-Term Functional Outcome and Health-Related Quality of Life after out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Resuscitation 2017, 113, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elisabet, E.; Waehrens, E.; Eastwood, G.; Kristensen, L.Q.; Eiskjaer, H.; Van Tulder, M.; Sørensen, L.; Bro-Je, J.; Gregersen Oestergaard, L. Early ADL Ability Assessment and Cognitive Screening as Markers of Post-Discharge Outcomes after Surviving an out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. A Prospective Cohort Study. Resuscitation 2025, 214, 110653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.; Eskildsen, S.J.; Gregers Winkel, B.; Kofoed Dichman, C.; Wagner, M.K. Motor and Process Skills in Activities of Daily Living in Survivors of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Cross-Sectional Study at Hospital Discharge. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2021, 20, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, V.L.; Tang, L.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Wagner, M.K.; Nielsen, J.F.; Tjoernlund, M.; Zwisler, A.D. Promising Results from a Residential Rehabilitation Intervention Focused on Fatigue and the Secondary Psychological and Physical Consequences of Cardiac Arrest: The SCARF Feasibility Study. Resuscitation 2022, 173, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Joshi, V.; Wu, Q. Subjective Factors of Depressive Symptoms, Ambulation, Pain, and Fatigue Are Associated with Physical Activity Participation in Cardiac Arrest Survivors with Fatigue. Resusc. Plus 2021, 5, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebsen, S.; Wieghorst, A.; Joshi, V.; Petersson, N.; Zwisler, A.; Borregaard, B. Fatigue across Age Groups Following Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: Results from the DANCAS Survey. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2025, 24, i157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, J.W.; Ng, Z.H.C.; Goh, A.X.C.; Gao, J.F.; Liu, N.; Lam, S.W.S.; Chia, Y.W.; Perkins, G.D.; Ong, M.E.H.; Ho, A.F.W. Impact of Cardiac Arrest Centers on the Survival of Patients with Nontraumatic Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e023806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, J.P.; Sandroni, C.; Cariou, A.; Cronberg, T.; D’Arrigo, S.; Haywood, K.; Hoedemaekers, A.; Lilja, G.; Nikolaou, N.; Olasveengen, T.M.; et al. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Guidelines 2025: Post-Resuscitation Care. Intensive Care Med. 2025, 51, 2213–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Lawton, R.; Parker, D.; Walker, A. Making Psychological Theory Useful for Implementing Evidence Based Practice: A Consensus Approach. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2005, 14, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gräsner, J.-T.; Herlitz, J.; Tjelmeland, I.B.M.; Wnent, J.; Masterson, S.; Lilja, G.; Bein, B.; Böttiger, B.W.; Rosell-Ortiz, F.; Nolan, J.P.; et al. Epidemiology of Cardiac Arrest in Europe. Resuscitation 2021, 161, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |