The Impact of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists on Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic Health in Romanian Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Clinical, Anthropometric, and Laboratory Data

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings and Their Interpretation

4.2. Strengths and Weaknesses

4.3. Relevance of the Findings and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASCVD | Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CKD-EPI | Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration |

| CV | Cardiovascular |

| CVOT | Cardiovascular outcome trial |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| FPG | Fasting plasma glucose |

| GLP-1 RA | Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| HDLc | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDLc | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| TyG | Triglyceride–glucose index |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| UA | Uric acid |

| UACR | Urinary albumin–creatinine ratio |

References

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Atlas, 11th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sattar, N.; Lee, M.M.Y.; Kristensen, S.L.; Branch, K.R.H.; Del Prato, S.; Khurmi, N.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Lopes, R.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Pratley, R.E.; et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 11. Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, S239–S251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.; Bakbak, E.; Teoh, H.; Krishnaraj, A.; Dennis, F.; Quan, A.; Rotstein, O.D.; Butler, J.; Hess, D.A.; Verma, S. GLP-1 receptor agonists and atherosclerosis protection: The vascular endothelium takes center stage. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 2024, 326, H1159–H1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górriz, J.L.; Soler, M.J.; Navarro-González, J.F.; García-Carro, C.; Puchades, M.J.; D’marco, L.; Castelao, A.M.; Fernández-Fernández, B.; Ortiz, A.; Górriz-Zambrano, C.; et al. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Diabetic Kidney Disease: A Call of Attention to Nephrologists. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, T.-H.; Tsai, M.-L.; Wu, V.C.-C.; Tseng, C.-J.; Lin, M.-S.; Li, Y.-R.; Chang, C.-H.; Chou, T.-S.; Tsai, T.-H.; et al. The cardiovascular and renal effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists in patients with advanced diabetic kidney disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, S181–S206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerstein, H.C.; Colhoun, H.M.; Dagenais, G.R.; Diaz, R.; Lakshmanan, M.; Pais, P.; Probstfield, J.; Riesmeyer, J.S.; Riddle, M.C.; Rydén, L.; et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): A double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, S. Follow the LEADER-Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results Trial. Diabetes Ther. 2016, 7, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, N.; Schütt, K.; Müller-Wieland, D.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Herrington, W.G.; A Ajjan, R.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; Rocca, B.; Sattar, N.; Fauchier, L.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes. Eur. Heart. J. 2023, 44, 4043–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauck, M.A.; Quast, D.R. Cardiovascular Safety and Benefits of Semaglutide in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: Findings From SUSTAIN 6 and PIONEER 6. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 645566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.F.E.; Rossing, P.; Bakris, G.; Belmar, N.; Bosch-Traberg, H.; Busch, R.; Charytan, D.M.; Hadjadj, S.; Gillard, P.; Górriz, J.L.; et al. Effects of semaglutide with and without concomitant SGLT2 inhibitor use in participants with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease in the FLOW trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2849–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htike, Z.Z.; Zaccardi, F.; Papamargaritis, D.; Webb, D.R.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J. Efficacy and safety of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and mixed-treatment comparison analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2017, 19, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.M.; Sattar, N.; Pop-Busui, R.; Deanfield, J.; Emerson, S.S.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Mann, J.F.; Marx, N.; Mulvagh, S.L.; Poulter, N.R.; et al. Cardiovascular and Kidney Outcomes and Mortality With Long-Acting Injectable and Oral Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists in Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Trials. Diabetes Care. 2025, 48, 846–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEvoy, J.W.; McCarthy, C.P.; Bruno, R.M.; Brouwers, S.; Canavan, M.D.; Ceconi, C.; Christodorescu, R.M.; Daskalopoulou, S.S.; Ferro, C.J.; Gerdts, E.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Eur. Heart. J. 2024, 45, 3912–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Diabetes Work, G. KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2022, 102, S1–S127. [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.R.; Soltani, S.; Meybodi, Z.H.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Firouzabadi, D.D.; Eshraghi, R.; Restrepo, D.; Ghoshouni, H.; Sarebanhassanabadi, M. Which surrogate insulin resistance indices best predict coronary artery disease? A machine learning approach. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Río, V.C.; Mostaza, J.; Lahoz, C.; Sánchez-Arroyo, V.; Sabín, C.; López, S.; Patrón, P.; Fernández-García, P.; Fernández-Puntero, B.; Vicent, D.; et al. Prevalence of peripheral artery disease (PAD) and factors associated: An epidemiological analysis from the population-based Screening PRE-diabetes and type 2 DIAbetes (SPREDIA-2) study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186220. [Google Scholar]

- Heffron, S.P.; Dwivedi, A.; Rockman, C.B.; Xia, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhong, J.; Berger, J.S. Body mass index and peripheral artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2020, 292, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosenzon, O.; Blicher, T.M.; Rosenlund, S.; Eriksson, J.W.; Heller, S.; Hels, O.H.; Pratley, R.; Sathyapalan, T.; Desouza, C.; Abramof, R.; et al. Efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate renal impairment (PIONEER 5): A placebo-controlled, randomised, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fala, L. Trulicity (Dulaglutide): A New GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Once-Weekly Subcutaneous Injection Approved for the Treatment of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Am. Health Drug Benefits 2015, 8, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Sorli, C.; Harashima, S.-I.; Tsoukas, G.M.; Unger, J.; Karsbøl, J.D.; Hansen, T.; Bain, S.C. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide monotherapy versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 1): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multinational, multicentre phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashayekhi, M.; Nian, H.; Mayfield, D.; Devin, J.K.; Gamboa, J.L.; Yu, C.; Silver, H.J.; Niswender, K.; Luther, J.M.; Brown, N.J. Weight Loss-Independent Effect of Liraglutide on Insulin Sensitivity in Individuals With Obesity and Prediabetes. Diabetes 2024, 73, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Huang, C.; Shen, X.; Li, J.; Zhou, S.; Li, W. GLP-1 RAs and SGLT-2 Inhibitors for Insulin Resistance in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 923606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lincoff, A.M.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Colhoun, H.M.; Deanfield, J.; Emerson, S.S.; Esbjerg, S.; Hardt-Lindberg, S.; Hovingh, G.K.; Kahn, S.E.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2221–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaita, L.; Timar, R.; Lupascu, N.; Roman, D.; Albai, A.; Potre, O.; Timar, B. The Impact Of Hyperuricemia On Cardiometabolic Risk Factors In Patients With Diabetes Mellitus: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2019, 12, 2003–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, F.B.; Lumbang, G.N.O.; Gaid, D.R.M.; Cruz, L.L.A.; Magalong, J.V.; Bsc, N.R.B.B.; Lara-Breitinger, K.M.; Gulati, M.; Bakris, G. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists modestly reduced blood pressure among patients with and without diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 2209–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Node, K.; Kobayashi, Y. Uric acid and cardiovascular disease: A clinical review. J. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkovic, V.; Tuttle, K.R.; Rossing, P.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Mann, J.F.; Bakris, G.; Baeres, F.M.; Idorn, T.; Bosch-Traberg, H.; Lausvig, N.L.; et al. Effects of Semaglutide on Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, S.H.; Yajnik, C.; Phatak, S.; Hanson, R.L.; Knowler, W.C. Racial/ethnic differences in the burden of type 2 diabetes over the life course: A focus on the USA and India. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 1751–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Overall | Men | Women | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 150 (100%) | 71 (47.3%) | 79 (52.7%) | - |

| Age (years) a | 62.00 [56.00; 67.00] | 62.00 (76.47) | 62.00 (74.62) | 0.749 |

| T2D duration (years) a | 14.00 [6.00; 17.00] | 14.00 (70.29) | 15.00 (80.17) | 0.163 |

| Weight (kg) a | 99.50 [90.00; 112.00] | 102.00 (84.43) | 97.00 (67.46) | 0.016 * |

| BMI (kg/m2) a | 35.00 [32.00; 39.00] | 34.00 (70.04) | 36.00 (80.39) | 0.145 |

| HbA1c (%) a | 8.70 [7.80; 9.93] | 8.70 (76.91) | 8.76 (74.22) | 0.705 |

| FPG (mg/dL) a | 189.00 [150.00; 245.00] | 200.00 (78.55) | 186.00 (72.75) | 0.414 |

| TC (mg/dL) a | 173.00 [150.60; 206.00] | 167.60 (73.66) | 173.80 (77.12) | 0.623 |

| LDLc (mg/dL) a | 95.00 [80.00; 121.00] | 95.00 (76.38) | 96.00 (74.70) | 0.814 |

| TG (mg/dL) a | 173.00 [139.00; 231.00] | 174.00 (76.27) | 173.00 (74.80) | 0.836 |

| HDLc (mg/dL) a | 38.00 [34.00; 43.00] | 36.00 (60.01) | 41.00 (89.41) | <0.0001 * |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) a | 85.85 [69.00; 100.00] | 93.00 (80.98) | 83.00 (70.56) | 0.142 |

| UACR (mg/g) a | 22.00 [10.30; 46.00] | 24.21 (81.52) | 20.30 (70.08) | 0.107 |

| SBP (mmHg) a | 140.00 [130.00; 146.00] | 140.00 (74.73) | 140.00 (76.18) | 0.836 |

| DBP (mmHg) a | 80.00 [78.00; 85.00] | 80.00 (74.78) | 80.00 (76.14) | 0.844 |

| UA (mg/dL) b | 5.20 ± 1.24 | 5.52 ± 1.30 | 4.92 ± 1.11 | 0.002 * |

| Variable a | Overall | Men | Women | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetic retinopathy | 45 (30.0%) | 21 (29.6%) | 24 (30.4%) | 0.915 |

| Diabetic polyneuropathy | 73 (48.7%) | 37 (52.1%) | 36 (45.6%) | 0.425 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 35 (23.3%) | 24 (33.8%) | 11 (13.9%) | 0.004 * |

| Chronic kidney disease | 82 (54.7%) | 35 (49.3%) | 47 (59.5%) | 0.211 |

| Coronary artery disease | 61 (40.7%) | 32 (45.1%) | 29 (36.7%) | 0.299 |

| Stroke | 26 (17.3%) | 15 (21.1%) | 11 (13.9%) | 0.246 |

| Heart failure | 42 (28.0%) | 20 (28.2%) | 22 (27.8%) | 0.965 |

| Hypertension | 126 (84.0%) | 61 (85.9%) | 65 (82.3%) | 0.545 |

| Parameter | Initially (a) | After 6 Months (b) | After 12 Months (c) | Difference a–b | Difference b–c | Difference a–c | Difference a–b–c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Median | Median | p y | p y | p y | p z | |

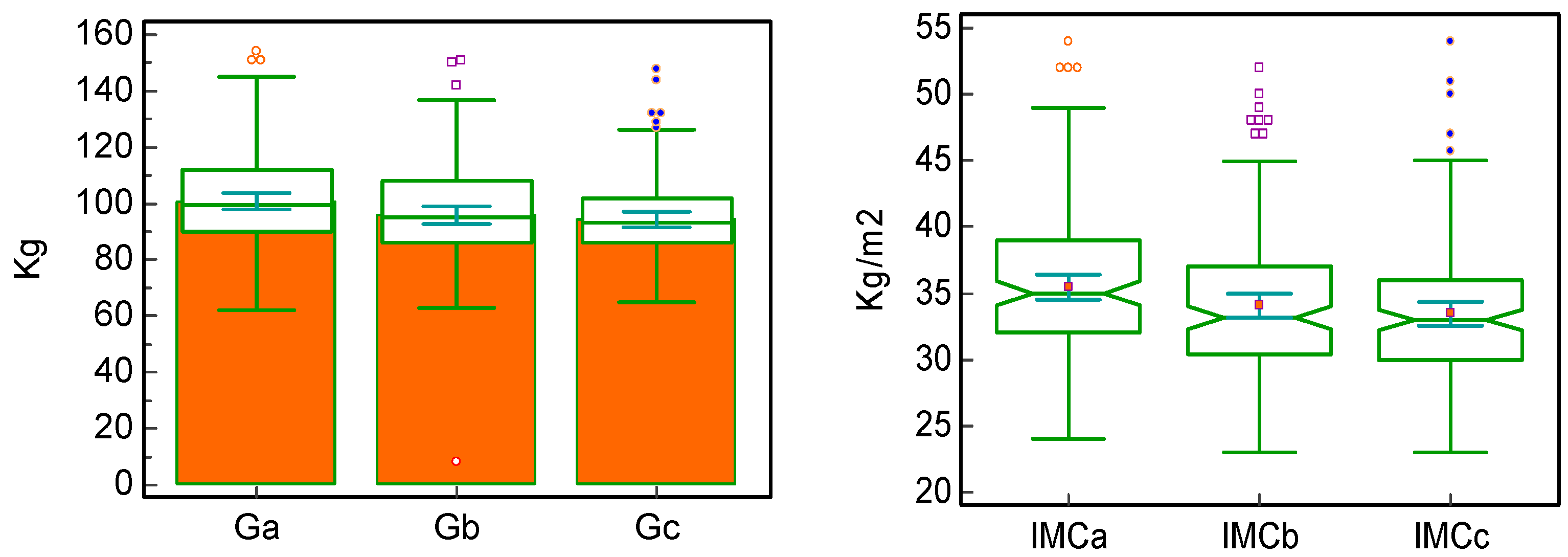

| Weight x | 99.50 [90; 112] | 95.00 [86; 108] | 93.00 [86; 102] | <0.0001 * | <0.0001 * | <0.0001 * | <0.00001 * |

| Paired difference | −4.00 | −2.00 | −6.00 | ||||

| BMI x | 35.00 | 33.15 | 33.00 | <0.0001 * | 0.0005 * | <0.0001 * | <0.00001 * |

| Paired difference | −1.10 | −0.80 | −2.00 | ||||

| HbA1c x | 8.70 [7.80; 9.93] | 7.95 [7.05; 9.0] | 7.90 [7.0; 9.0] | <0.0001 * | 0.0234 * | <0.0001 * | <0.00001 * |

| Paired difference | −0.73 | −0.00 | −0.80 | ||||

| FPG x | 189.00 | 164.00 | 146.00 | <0.0001 * | <0.0001 * | <0.0001 * | <0.00001 * |

| Paired difference | −14.50 | −11.50 | −38.50 | ||||

| Parameter | Initially | After 12 Months | Paired Difference | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

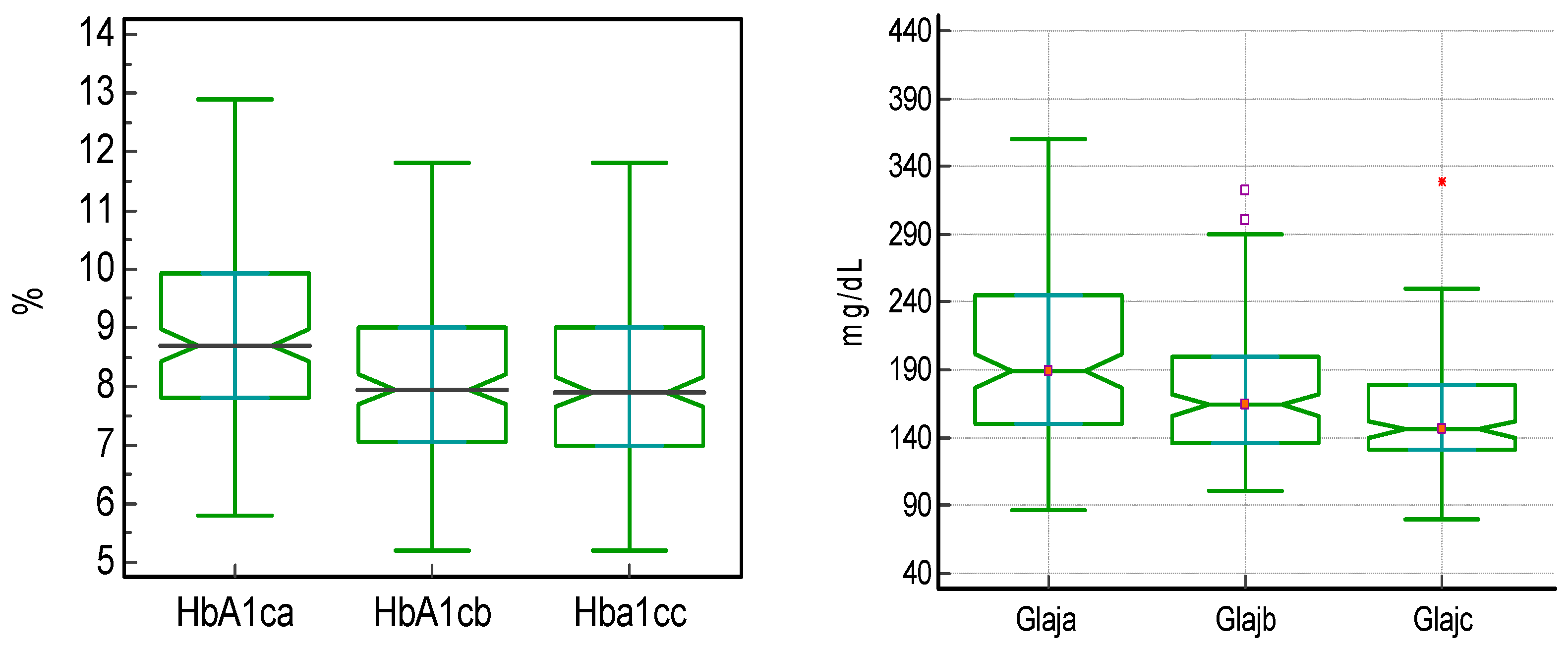

| LDLc (mg/dL) | 95.50 | 88.50 | −8.00 | <0.0001 * |

| HDLc (mg/dL) | 38.00 | 42.00 | 4.00 | <0.0001 * |

| TG (mg/dL) | 173.50 | 154.00 | −19.00 | <0.0001 * |

| SBP (mmHg) | 140.00 | 130.00 | −5.00 | <0.0001 * |

| DBP (mmHg) | 80.00 | 80.00 | 0.00 | 0.042 * |

| UA (mg/dL) | 5.00 | 4.85 | −0.35 | <0.0001 * |

| UACR (mg/g) | 22.00 | 19.04 | −1.92 | 0.481 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 85.85 | 85.50 | −1.17 | <0.0001 * |

| Parameter | Initially | After 12 Months | p |

|---|---|---|---|

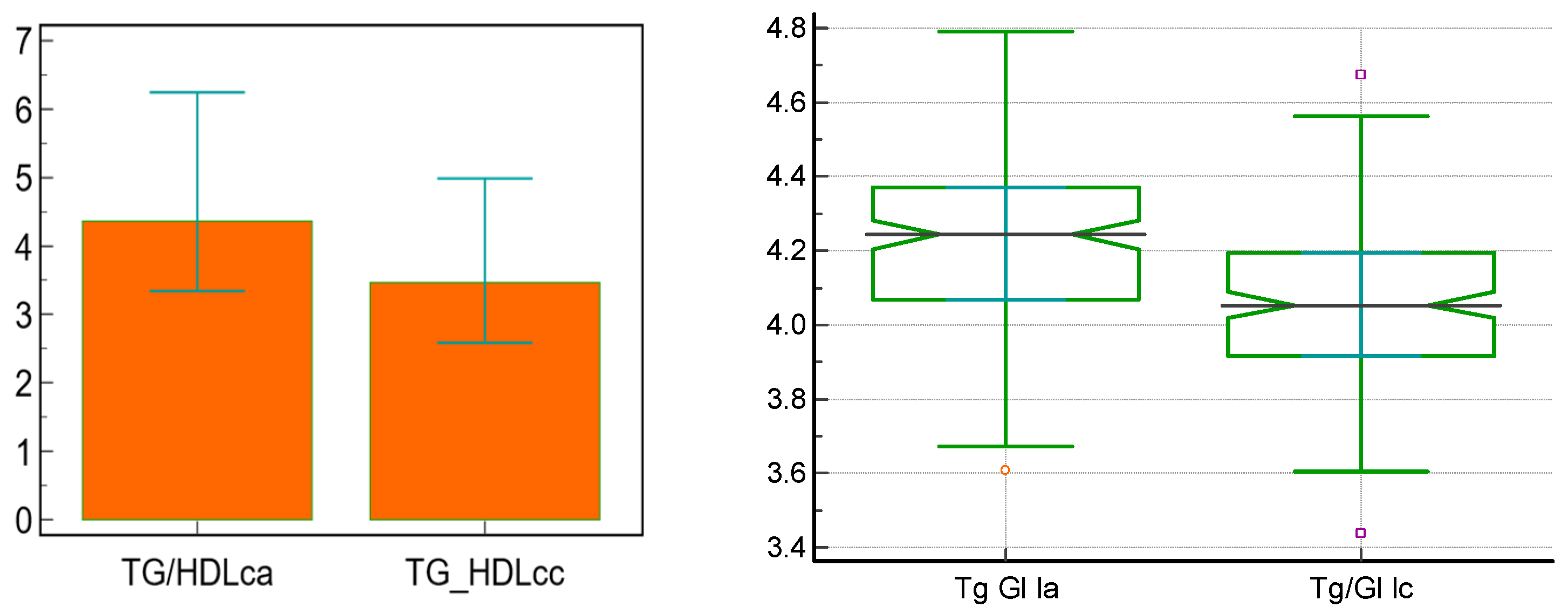

| Tg/HDLc | 4.35 [3.34; 6.24] | 3.46 [2.58; 4.98] | <0.0001 * |

| TyG | 4.24 [4.06; 4.36] | 4.05 [3.91; 4.19] | <0.0001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lixandru, N.; Gaita, L.; Popescu, S.; Herascu, A.; Timar, B.; Timar, R. The Impact of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists on Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic Health in Romanian Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010152

Lixandru N, Gaita L, Popescu S, Herascu A, Timar B, Timar R. The Impact of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists on Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic Health in Romanian Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):152. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010152

Chicago/Turabian StyleLixandru, Niculina, Laura Gaita, Simona Popescu, Andreea Herascu, Bogdan Timar, and Romulus Timar. 2026. "The Impact of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists on Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic Health in Romanian Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Retrospective Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010152

APA StyleLixandru, N., Gaita, L., Popescu, S., Herascu, A., Timar, B., & Timar, R. (2026). The Impact of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists on Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic Health in Romanian Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010152