Biomechanical Investigations of a New Model Graft Attachment to Distal Phalanx in Two-Stage Flexor Tendon Reconstruction

Abstract

1. Introduction

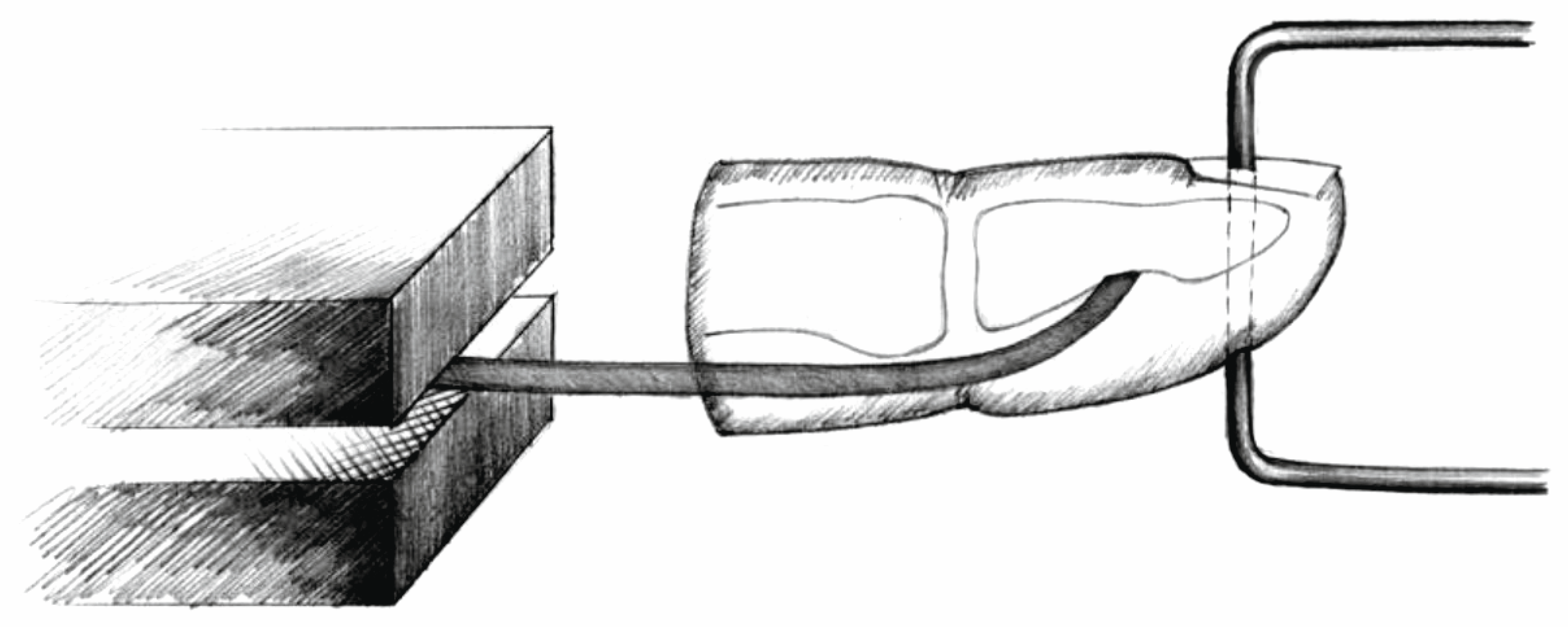

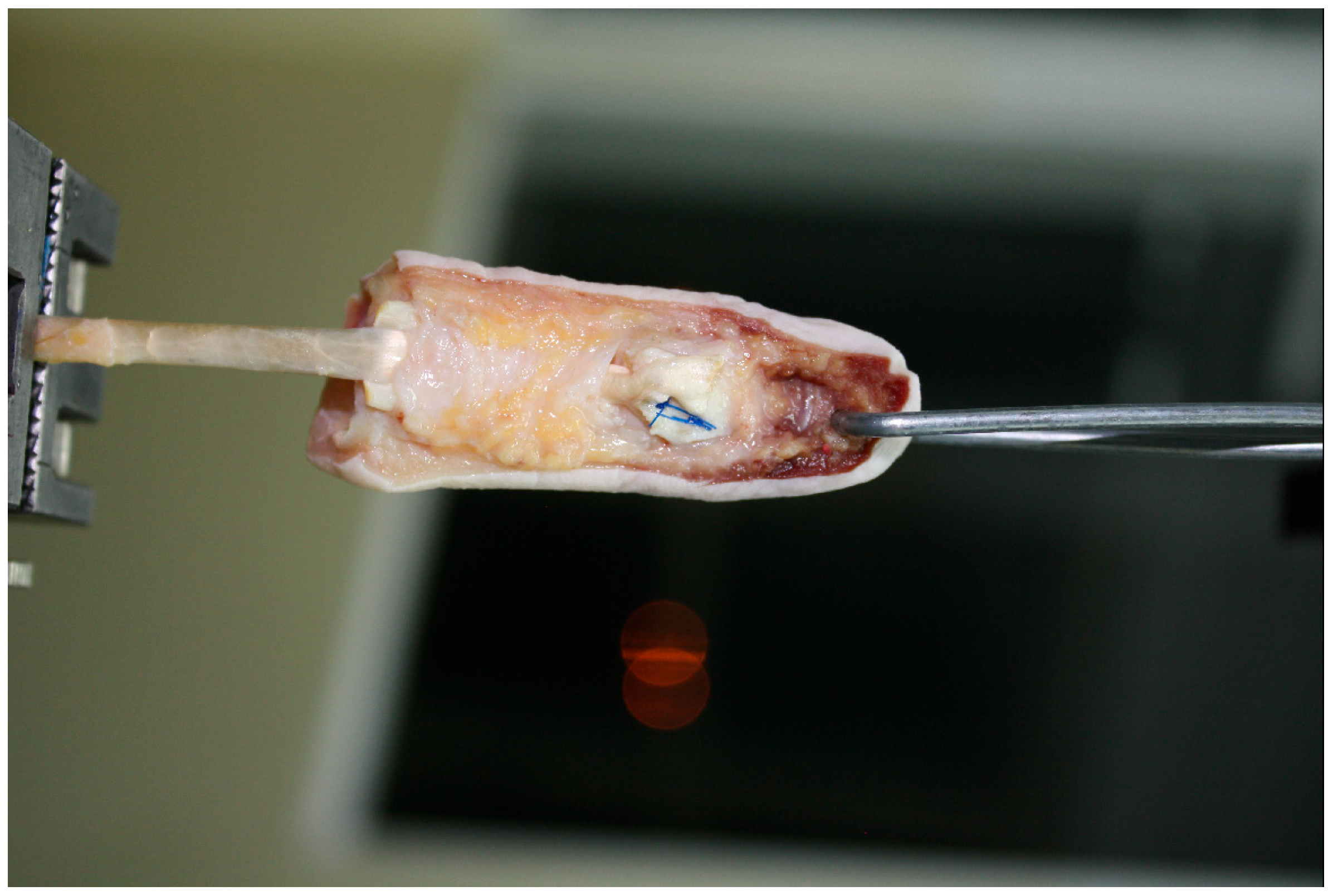

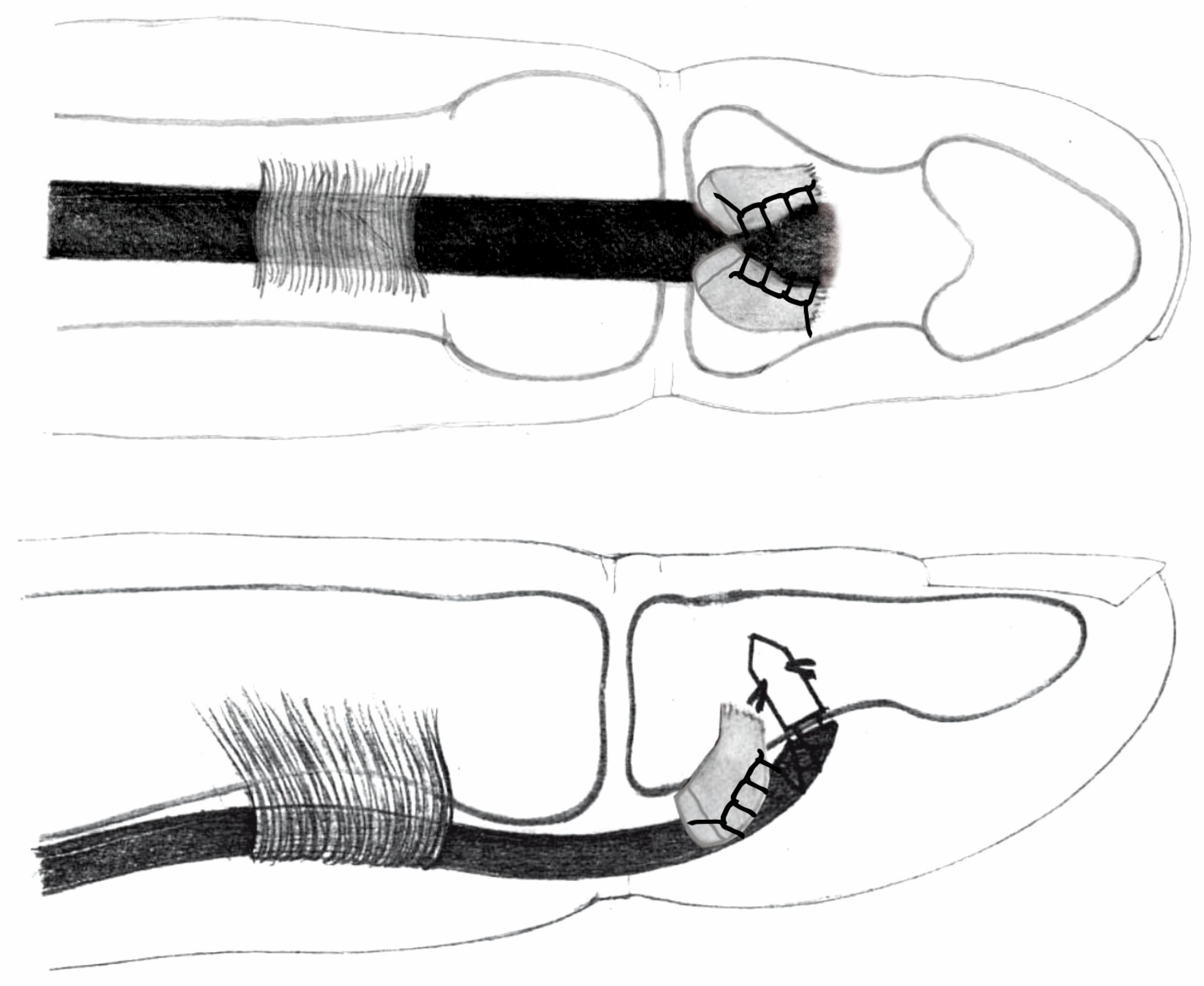

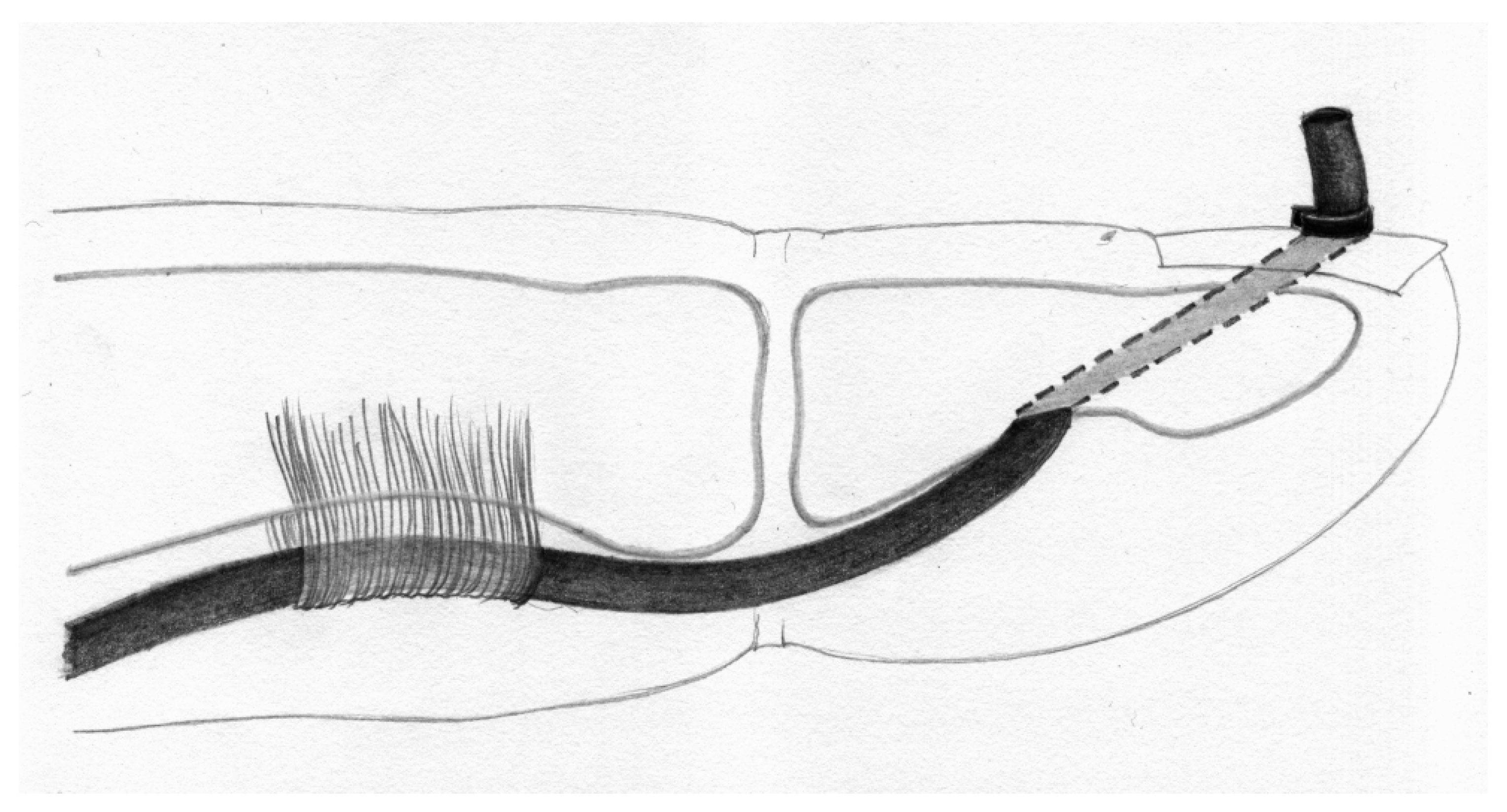

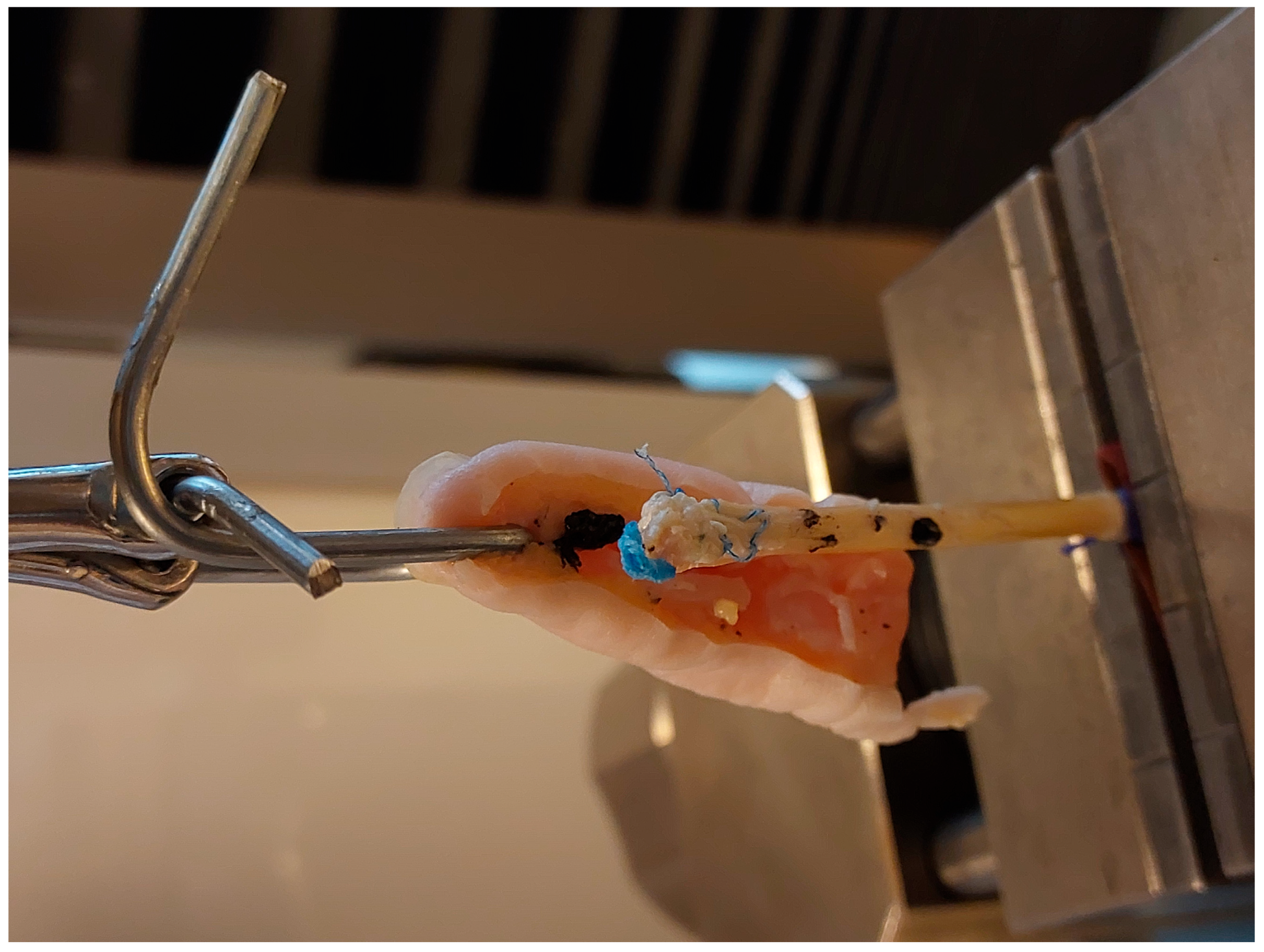

2. Materials and Methods

- Graft pull-out (suture-induced graft damage).

- Suture rupture.

- Anchor pull-out (Figure 6).

3. Results

4. Discussion

- Palmaris longus to flexor digitorum profundus (PL-FDP): force at rupture averaged 20.09 N (SD 6.25), elongation after applications of 20 N was 11.61 mm (SD 0.32). Among the eight specimens, seven exhibited graft pull-out, one showed suture rupture.

- Palmaris longus above the nail (PL-N) (Snow–Littler technique [12]): mean force at rupture was 9.16 N (SD 0.95), elongation after applications of 20 N was impossible in all specimens. Among the eight specimens, all eight exhibited graft pull-out.

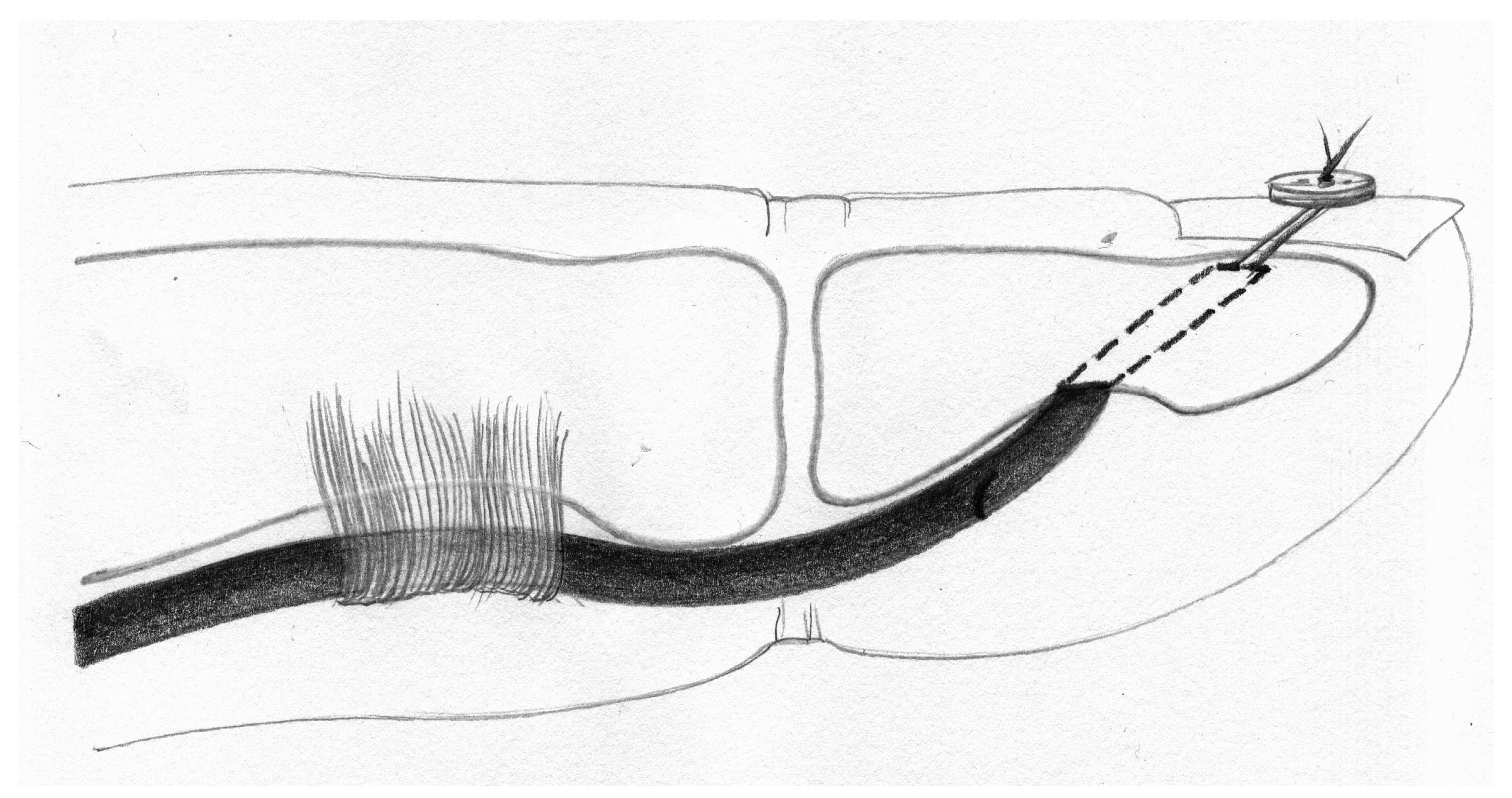

- Palmaris longus to the bone (PL-B) (Wilson technique, Figure 5): force at rupture was 26.23 N (SD 5.81), elongation after applications of 20 N was 11.23 mm (SD 1.74). Among the eight specimens, all eight exhibited suture rupture.

- Palmaris longus to anchor connection (PL-A): force at rupture was 32.15 N (SD 2.37), elongation after applications of 20 N was 9.34 mm (SD 1.37). Among the eight specimens, all eight exhibited suture rupture.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bunnell, S. Primary Repair of Severed Tendons the Use of Stainless Steel Wire. Am. J. Surg. 1940, 47, 502–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, M.P.; Leddy, T.P.; Leddy, J.P. Staged Flexor Tendon Reconstruction Fingertip to Palm. J. Hand Surg. 2002, 27, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Jones, M.; Grobbelaar, A. Two-Stage Grafting of Flexor Tendons: Results after Mobilisation by Controlled Early Active Movement. Scand. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Hand Surg. 2004, 38, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuind, F.; Garcia-Elias, M.; Cooney, W.P.; An, K.N. Flexor Tendon Forces: In Vivo Measurements. J. Hand Surg. Am. 1992, 17, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, M.I.; Strickland, J.W.; Engles, D.; Sachar, K.; Leversedge, F.J. Flexor Tendon Repair and Rehabilitation: State of the Art in 2002. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2002, 84, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brustein, M.; Pellegrini, J.; Choueka, J.; Heminger, H.; Mass, D. Bone Suture Anchors versus the Pullout Button for Repair of Distal Profundus Tendon Injuries: A Comparison of Strength in Human Cadaveric Hands. J. Hand Surg. 2001, 26, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, H.; Zaegel, M.A.; Gelberman, R.H.; Silva, M.J. Effect of Suture Material and Bone Quality on the Mechanical Properties of Zone I Flexor Tendon-Bone Reattachment with Bone Anchors. J. Hand Surg. 2008, 33, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, T.A. Secondary repair of flexor tendon injuries in the “no man’s land”—A clinical and experimental study. Ann. Acad. Medicae Gedanensis 2011, 10, 9–106. [Google Scholar]

- McNally, T.A.; Hamman, J.J.; Heminger, H.; Mass, D.P. The Strength of Distal Fixation of Flexor Digitorum Profundus Tendon Grafts in Human Cadavers. J. Hand Surg. 2002, 27, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriya, K.; Yoshizu, T.; Maki, Y. Flexor Tendon Grafting Using Extrasynovial Tendons Followed by Early Active Mobilization. J. Hand Surg. Glob. Online 2020, 2, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.J.; Hollstien, S.B.; Brodt, M.D.; Boyer, M.I.; Tetro, A.M.; Gelberman, R.H. Flexor Digitorum Profundus Tendon-to-Bone Repair: An Ex Vivo Biomechanical Analysis of 3 Pullout Suture Techniques. J. Hand Surg. Am. 1998, 23, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snow, J.W.; Littler, J.W. A Non-Suture Distal Fixation Technique for Tendon Grafts. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1971, 47, 91–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, M.K.; Elliot, D. A New Technique of Attachment of Flexor Tendons to the Distal Phalanx without a Button Tie-Over. J. Hand Surg. Eur. Vol. 1996, 21, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.B. Tendon Injuries across the World: Treatment. Injury 2006, 37, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, S.F. A New Modification of Two-Stage Flexor Tendon Reconstruction. Tech. Hand Up. Extrem. Surg. 2006, 10, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Thoreson, A.R.; Amadio, P.C.; An, K.N.; Zhao, C. Distal Attachment of Flexor Tendon Allograft: A Biomechanical Study of Different Reconstruction Techniques in Human Cadaver Hands. J. Orthop. Res. 2013, 31, 1720–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, D.L.; Hoffman, S.; Barsky, A.J. Improved Method for Distal Attachment of Flexor Tendon Grafts. Modification of Stenström Technique. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1968, 41, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.; Sammut, D. Flexor Tendon Graft Attachment: A Review of Methods and a Newly Modified Tendon Graft Attachment. J. Hand Surg. 2003, 28B, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, T.; Strankowski, M.; Ceynowa, M.; Rocławski, M. Tensile Strength of a Weave Tendon Suture Using Tendons of Different Sizes. Clin. Biomech. 2011, 26, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.L. Division of the Flexor Tendons within the Digital Sheath. Surg. Gynecol. Obs. 1978, 78, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pulvertaft, R.G. Suture Materials and Tendon Junctions. Am. J. Surg. 1965, 109, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulvertaft, R.G. Tendon Grafts for Flexor Tendon Injuries in the Fingers and Thumb. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1956, 38B, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silfverskiöld, K.L.; May, E.J. Early Active Mobilization of Tendon Grafts Using Mesh Reinforced Suture Techniques. J. Hand Surg. Br. 1995, 20, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, J.B.; Eyre-Brook, A.L. The Surgical Treatment of Flexor Tendon Injuries in the Hand: Results Obtained a Consecutive Series of 57 Cases. Br. J. Surg. 1954, 41, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubiana, R. Grafts of the flexor tendons of the fingers and of the thumb. Technic and results. Rev. Chir. Orthop. Reparatrice Appar. Mot. 1960, 46, 191–214. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R.L. Flexor Tendon Grafting. Hand Clin. 1985, 1, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, W.A.; Schlicht, S.M. The Plantaris Tendon as a Tendo-Osseous Graft. Part II. Clinical Studies. J. Hand Surg. Br. 1992, 17, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latendresse, K.; Dona, E.; Scougall, P.J.; Schreuder, F.B.; Puchert, E.; Walsh, W.R. Cyclic Testing of Pullout Sutures and Micro-Mitek Suture Anchors in Flexor Digitorum Profundus Tendon Distal Fixation. J. Hand Surg. Am. 2005, 30, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallister, W.V.; Ambrose, H.C.; Katolik, L.I.; Trumble, T.E. Comparison of Pullout Button versus Suture Anchor for Zone I Flexor Tendon Repair. J. Hand Surg. Am. 2006, 31, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoff, H.D.; Hecker, A.T.; Hayes, W.C.; Sebell-Sklar, R.; Straughn, N. Bone Suture Anchors in Hand Surgery. J. Hand Surg. Br. 1995, 20, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silfverskiöld, K.L.; Andersson, C.H. Two New Methods of Tendon Repair: An in Vitro Evaluation of Tensile Strength and Gap Formation. J. Hand Surg. Am. 1993, 18, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelberman, R.H.; Woo, S.L.Y.; Lothringer, K.; Akeson, W.H.; Amiel, D. Effects of Early Intermittent Passive Mobilization on Healing Canine Flexor Tendons. J. Hand Surg. Am. 1982, 7, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Specimen | Maximum Force at Failure (N) | Extension at 20 N (mm) | Mechanism of Failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42.39 | 5.06 | Anchor pullout |

| 2 | 52.7 | 1.7 | Anchor pullout |

| 3 | 16.5 | 3.68 | Graft pullout |

| 4 | 27.6 | 4.74 | Anchor pullout |

| 5 | 45.1 | 5.09 | Suture rupture |

| 6 | 64.6 | 1.49 | Anchor pullout |

| 7 | 62.0 | 2.71 | Anchor pullout |

| 8 | 43.2 | 9.14 | Suture rupture |

| Mean | 44.53 | 4.08 | |

| Standard Deviation | 17.56 | 2.63 |

| Mechanism of Failure | Maximum Force at Failure (N) | Extension at 20 N (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Anchor pullout | 49.86 | 3.14 |

| Graft pullout | 16.5 | 3.68 |

| Suture rupture | 44.15 | 7.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mazurek, T.; Żerdzicki, K.; Napora, J.; Ceynowa, M. Biomechanical Investigations of a New Model Graft Attachment to Distal Phalanx in Two-Stage Flexor Tendon Reconstruction. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010141

Mazurek T, Żerdzicki K, Napora J, Ceynowa M. Biomechanical Investigations of a New Model Graft Attachment to Distal Phalanx in Two-Stage Flexor Tendon Reconstruction. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010141

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazurek, Tomasz, Krzysztof Żerdzicki, Justyna Napora, and Marcin Ceynowa. 2026. "Biomechanical Investigations of a New Model Graft Attachment to Distal Phalanx in Two-Stage Flexor Tendon Reconstruction" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010141

APA StyleMazurek, T., Żerdzicki, K., Napora, J., & Ceynowa, M. (2026). Biomechanical Investigations of a New Model Graft Attachment to Distal Phalanx in Two-Stage Flexor Tendon Reconstruction. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010141