Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: From Molecular Pathways to Therapeutic Targets—A Mechanism-to-Practice Framework Integrating Pharmacotherapy, Fall Prevention, and Adherence into Patient-Centered Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

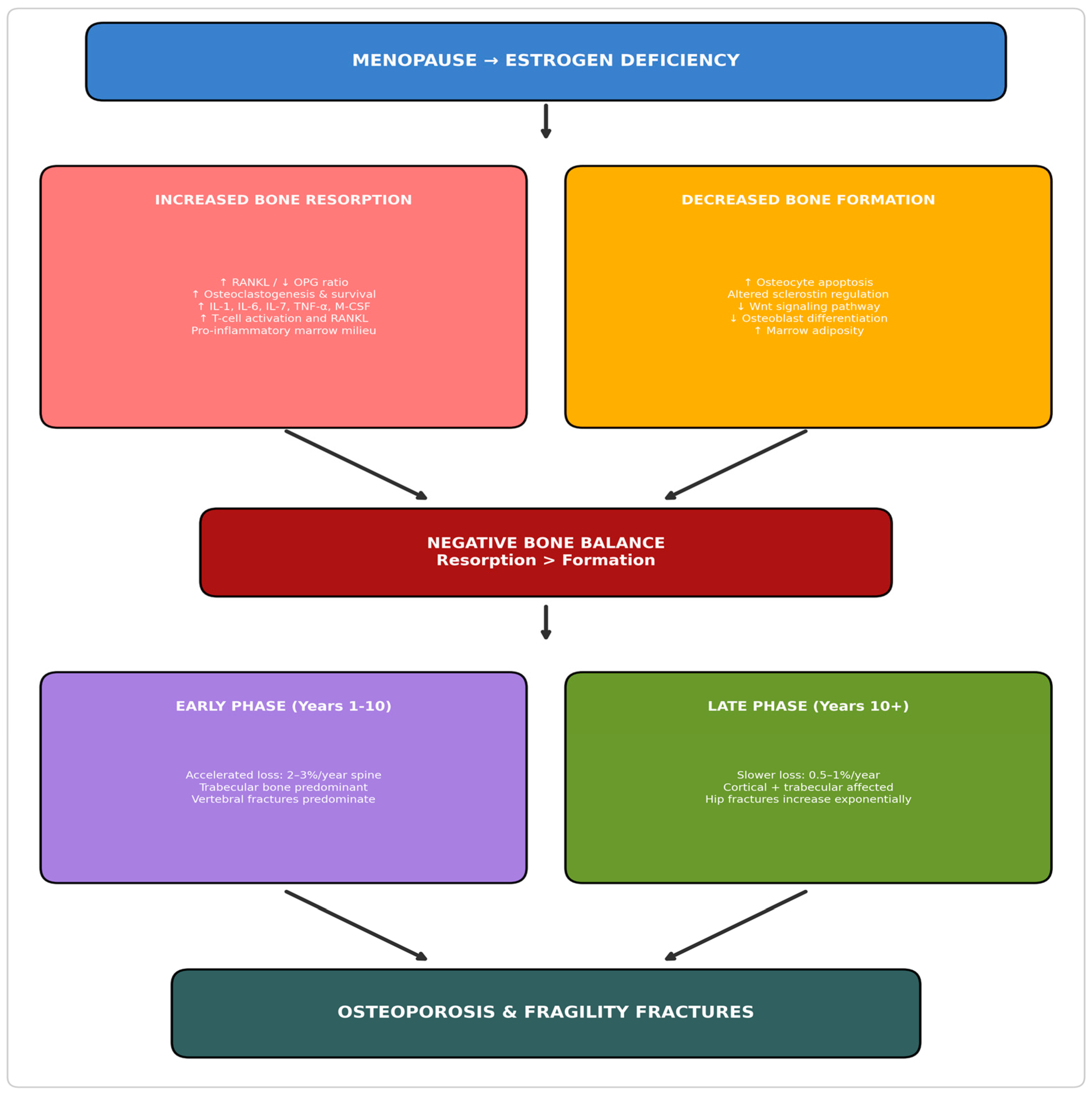

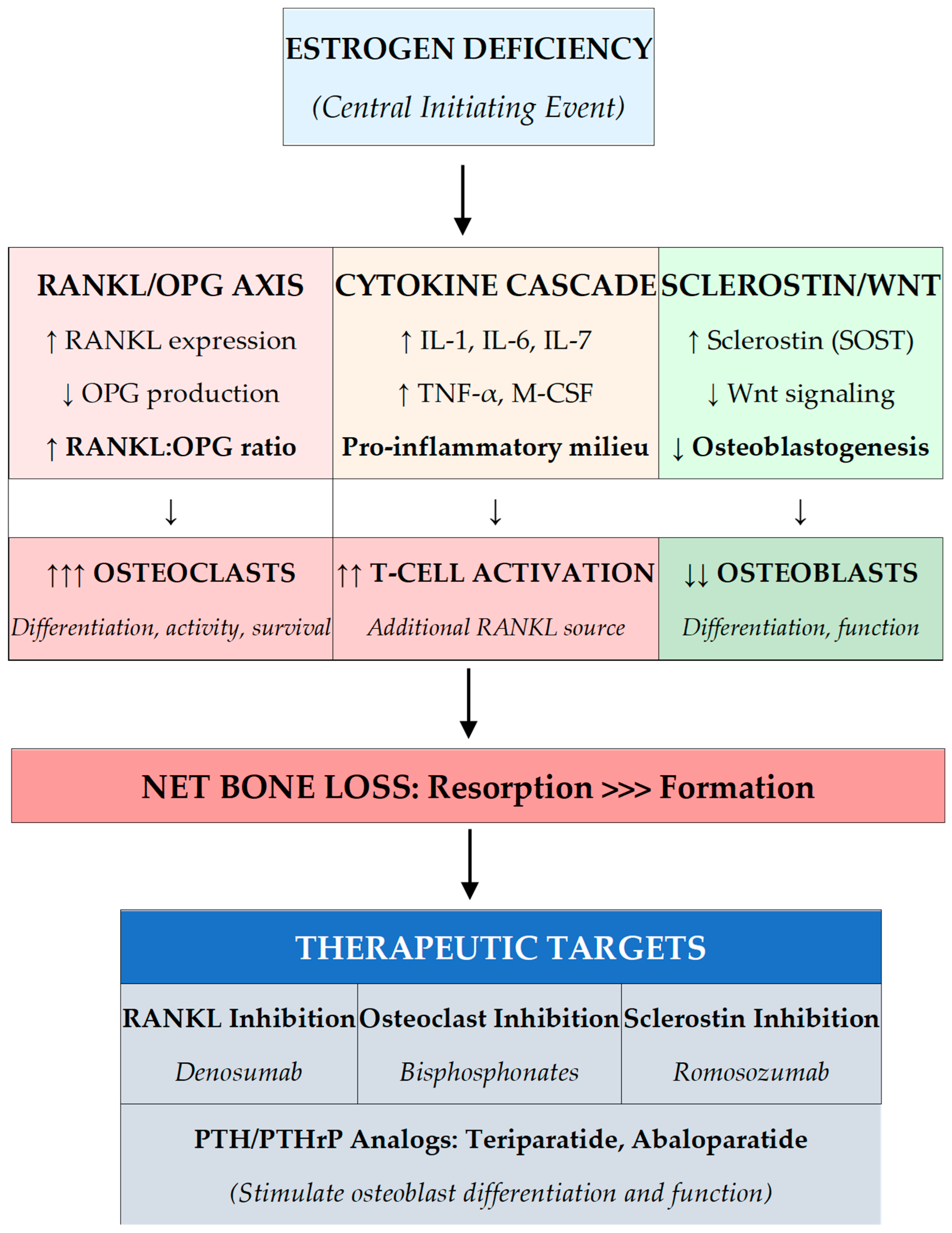

2. Pathophysiology of Postmenopausal Bone Loss

2.1. Estrogen Deficiency and the RANKL-OPG Axis

2.2. Inflammatory Cytokine Activation

2.3. Osteocyte Dysfunction and Sclerostin

2.4. Temporal Phases of Postmenopausal Bone Loss

2.5. Genetic and Epigenetic Factors

3. Diagnostic Evaluation

3.1. Clinical Assessment and Risk Factor Identification

3.2. Fracture Risk Assessment Tools

3.3. Laboratory Evaluation

3.4. Systematic Clinical Evaluation: What to Ask and Assess

4. Bone Mineral Density Evaluation: When to Perform DXA

4.1. Indications for Initial DXA Screening

4.2. Frequency of Repeat DXA Testing

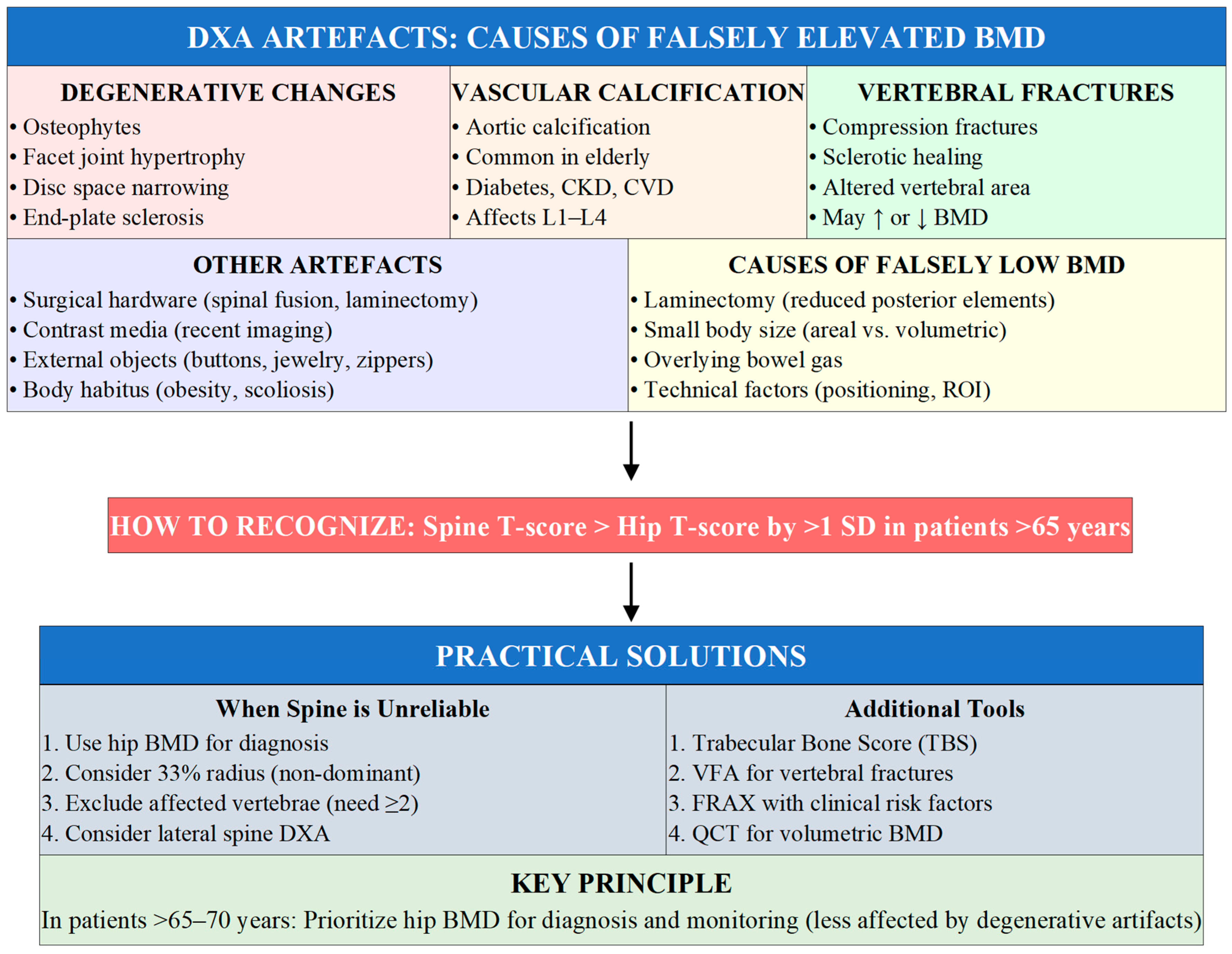

4.3. Limitations of DXA and Practical Adaptations

5. Treatment Strategies

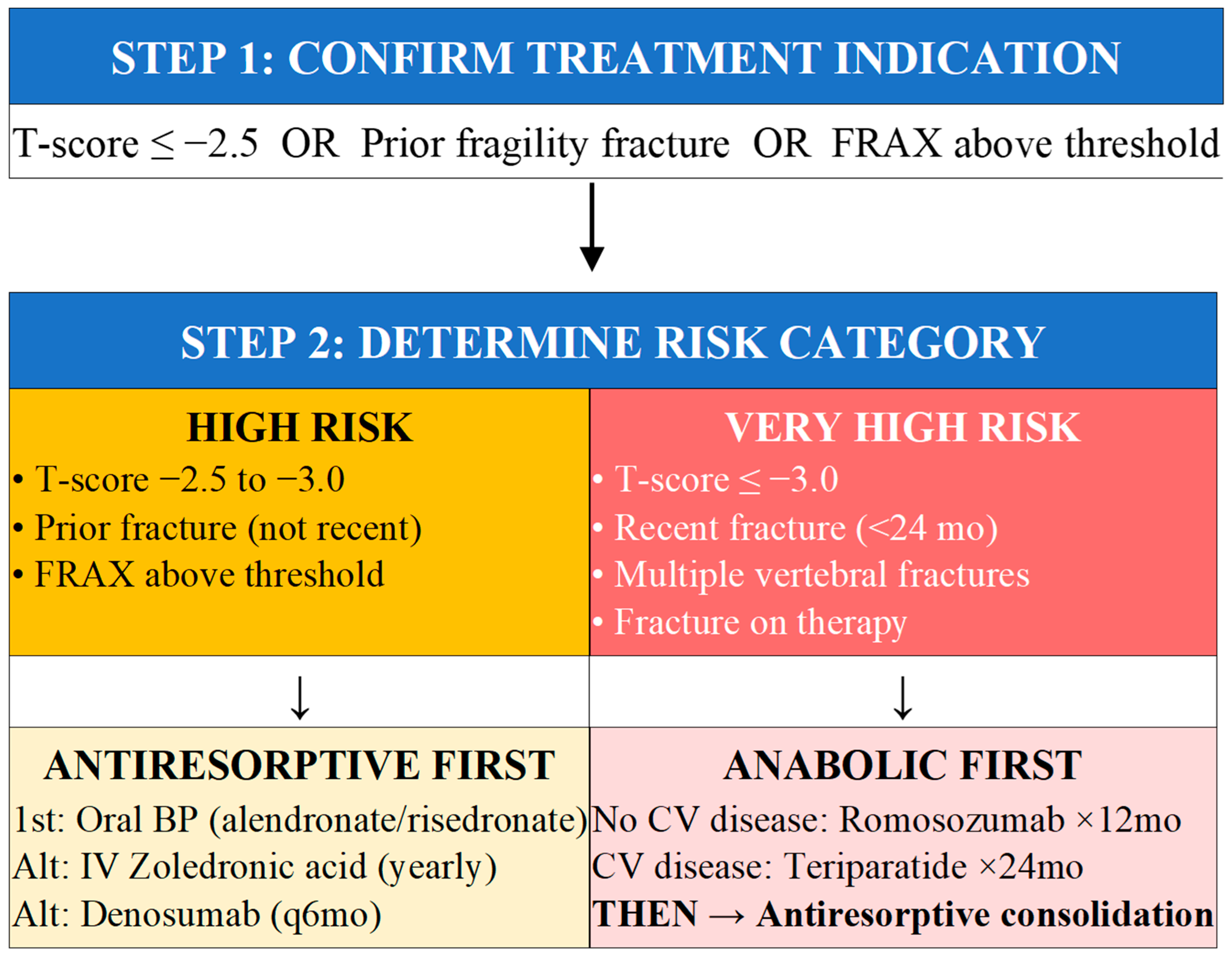

5.1. Treatment Indications and Risk Stratification

5.2. Algorithm for Initial Treatment Selection

5.3. Non-Pharmacological Interventions

5.4. Fall Prevention: A Critical Component of Fracture Risk Reduction

5.4.1. Fall Risk Assessment

5.4.2. Medication Review

5.4.3. Vision Assessment and Correction

5.4.4. Exercise and Physical Therapy

5.4.5. Home Safety Modifications

5.4.6. Footwear

5.4.7. Management of Orthostatic Hypotension

5.4.8. Vitamin D for Fall Prevention

6. Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ)

6.1. Definition and Clinical Presentation

6.2. Pathophysiology

6.3. Incidence and Risk Factors

6.4. Prevention Strategies

6.5. Addressing Dental Anxiety in Patients and Healthcare Providers

6.5.1. Contextualizing the Risk: Putting MRONJ in Perspective

6.5.2. Guidance for Dental Practitioners

6.5.3. Reassuring Patients: Key Messages

6.5.4. Communication Between Physicians and Dentists

7. When and How to Stop Antiresorptive Therapy

7.1. Rationale for Considering Discontinuation

7.2. Atypical Femoral Fractures: Recognition and Management

7.3. Bisphosphonate Drug Holidays

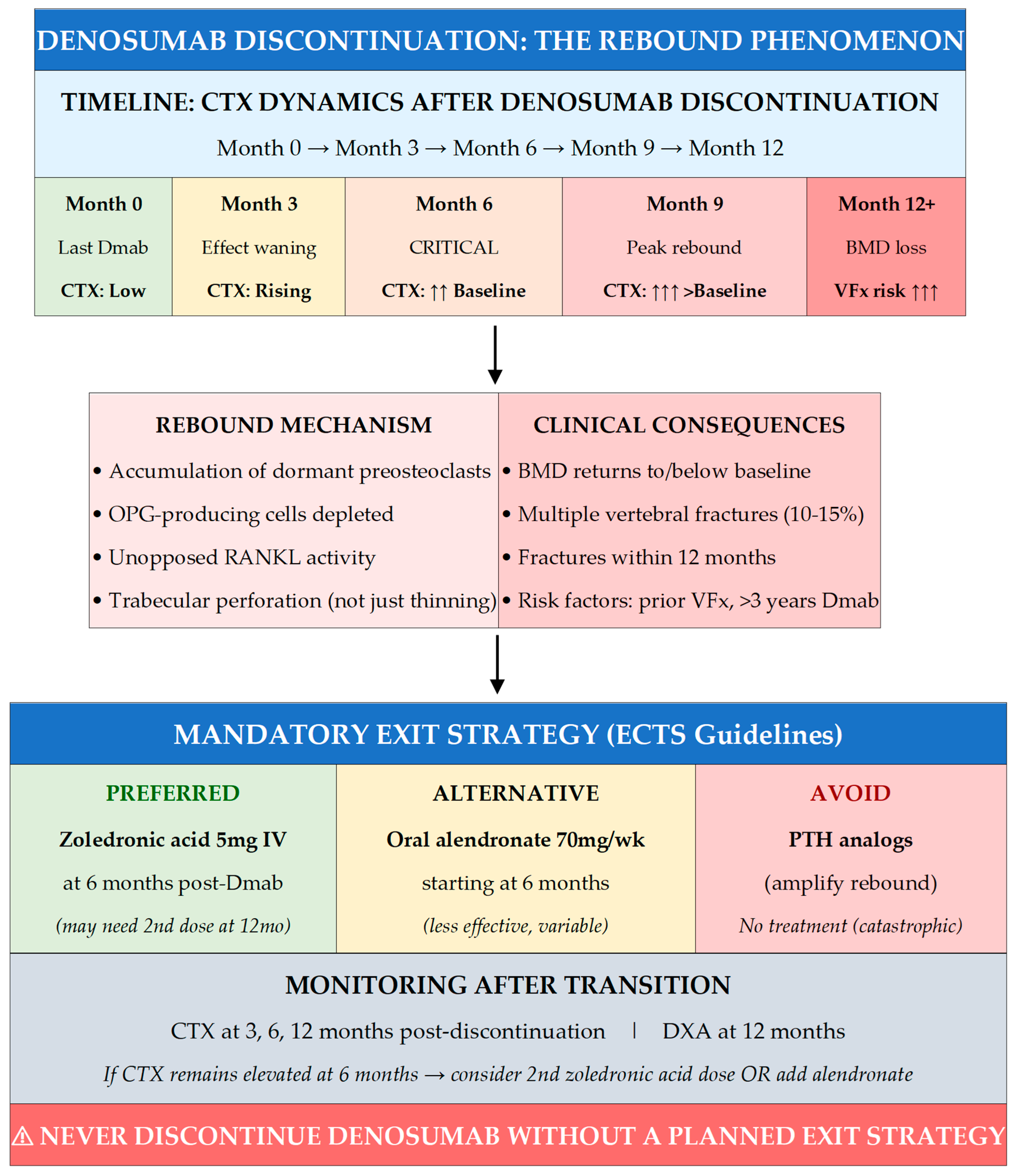

7.4. Denosumab Discontinuation: The Rebound Phenomenon

7.5. Exit Strategies After Denosumab

8. Conclusions

9. Key Points

- Estrogen deficiency drives postmenopausal bone loss through three interconnected mechanisms: ↑RANKL/↓OPG ratio, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and ↑sclerostin—each representing a therapeutic target.

- Screen all women ≥65 years; screen younger postmenopausal women with risk factors (prior fracture, parental hip fracture, glucocorticoids, low BMI, smoking).

- Match treatment intensity to risk: HIGH risk → antiresorptive first; VERY HIGH risk (recent fracture, T-score ≤ −3.0) → anabolic first, then consolidate.

- MRONJ risk with osteoporosis-dose therapy is ~1:10,000–100,000/year—100× lower than oncology dosing; routine dental care can proceed; fear should not preclude treatment.

- Never stop denosumab without exit strategy: transition to zoledronic acid at 6 months to prevent rebound vertebral fractures (10–15% incidence without transition).

10. Key Practice Points

- 1.

- WHO SHOULD BE SCREENED

- All women aged ≥ 65 years (universal screening).

- Postmenopausal women <65 years with risk factors: prior fragility fracture, parental hip fracture, low body weight (<58 kg or BMI < 20), current smoking, excess alcohol (≥3 units/day), rheumatoid arthritis, early menopause (<45 years), or FRAX ≥ 10%.

- Any patient on glucocorticoids (≥5 mg/day for ≥ 3 months), aromatase inhibitors, or with conditions causing secondary osteoporosis.

- Patients with vertebral fractures or height loss (>4 cm historical or >2 cm prospective) on imaging.

- 2.

- SIMPLE TREATMENT ALGORITHM BY RISK CATEGORY

- HIGH RISK (T-score ≤ −2.5, prior fracture, FRAX above threshold): Start antiresorptive therapy—oral bisphosphonates as first-line (alendronate, risedronate); alternatives include IV zoledronic acid annually or denosumab every 6 months.

- VERY HIGH RISK (T-score ≤ −3.0, recent fracture < 24 months, multiple vertebral fractures, fracture on therapy): Start osteoanabolic therapy first—romosozumab × 12 months (if no cardiovascular disease) or teriparatide/abaloparatide × 24 months, THEN consolidate with antiresorptive.

- ALL PATIENTS: Ensure calcium 1000–1200 mg/day, vitamin D 800–2000 IU/day (target 25(OH)D ≥ 50 nmol/L), weight-bearing exercise, fall prevention, and smoking/alcohol cessation.

- 3.

- HOW TO MANAGE MRONJ FEARS

- Contextualize the risk: MRONJ incidence with osteoporosis-dose therapy is 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 100,000 patient-years—comparable to background ONJ risk and far lower than risks of aspirin GI bleeding (1 in 1000/year) or untreated osteoporosis (17% lifetime hip fracture risk).

- Distinguish osteoporosis dosing from oncology dosing: Denosumab 60 mg q6mo or zoledronic acid 5 mg/year (osteoporosis) carries 100-fold lower MRONJ risk than denosumab 120 mg monthly or zoledronic acid 4 mg monthly (cancer).

- Reassure patients and dentists: Routine dental care including extractions CAN proceed; good oral hygiene actually REDUCES MRONJ risk; drug holidays before dental procedures are generally NOT necessary for bisphosphonates.

- Emphasize the alternative: Refusing osteoporosis treatment due to MRONJ fear exposes patients to far greater, more certain harm from fractures—the benefit–risk ratio strongly favors treatment.

- 4.

- MANDATORY PLANNING FOR DENOSUMAB EXIT STRATEGIES

- NEVER discontinue denosumab without a planned exit strategy—rebound bone turnover causes 10–15% incidence of multiple vertebral fractures within 12 months of stopping.

- Preferred transition: Administer zoledronic acid 5 mg IV at 6 months after the last denosumab dose (when due for next injection); may require second dose at 12 months if CTX remains elevated.

- Monitor with CTX at 3, 6, and 12 months post-discontinuation; DXA at 12 months.

- AVOID switching to PTH analogs (amplify rebound); oral bisphosphonates are less effective than IV zoledronic acid for preventing rebound.

- Counsel patients BEFORE starting denosumab about this long-term commitment and transition requirements.

- 5.

- FALL PREVENTION IS FRACTURE PREVENTION

- Over 90% of hip fractures result from falls—address both bone fragility AND fall risk for comprehensive fracture prevention.

- Key interventions: Exercise programs with balance training (Tai Chi reduces falls by 40–50%), medication review (reduce sedatives, manage orthostatic hypotension), vision correction, home safety modifications, appropriate footwear.

- Screen with Timed Up and Go test (>12 s indicates increased risk) and fall history (≥2 falls or 1 injurious fall in past year warrants comprehensive assessment).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kanis, J.A.; Cooper, C.; Rizzoli, R.; Reginster, J.Y. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos. Int. 2019, 30, 3–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compston, J.E.; McClung, M.R.; Leslie, W.D. Osteoporosis. Lancet 2019, 393, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, S.; Oursler, M.J.; Monroe, D.G. Estrogen and the skeleton. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 23, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernlund, E.; Svedbom, A.; Ivergård, M.; Compston, J.; Cooper, C.; Stenmark, J.; McCloskey, E.V.; Jönsson, B.; Kanis, J.A. Osteoporosis in the European Union: Medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. Arch Osteoporos. 2013, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnell, O.; Kanis, J.A. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos. Int. 2006, 17, 1726–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, F.; Moldovan, L. The impact of total hip arthroplasty on the incidence of hip fractures in Romania. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, D.H.; Johnston, S.S.; Boytsov, N.N.; McMorrow, D.; Lane, J.M.; Krohn, K.D. Osteoporosis medication use after hip fracture in U.S. patients between 2002 and 2011. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 1929–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosla, S.; Monroe, D.G. Regulation of bone metabolism by sex steroids. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a031211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manolagas, S.C. From estrogen-centric to aging and oxidative stress: A revised perspective of the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Endocr. Rev. 2010, 31, 266–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzmann, M.N.; Pacifici, R. Estrogen deficiency and bone loss: An inflammatory tale. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifici, R. T cells, osteoblasts, and osteocytes: Interacting lineages key for the bone anabolic and catabolic activities of parathyroid hormone. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2016, 1364, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robling, A.G.; Bonewald, L.F. The osteocyte: New insights. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2020, 82, 485–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.; Kneissel, M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: From human mutations to treatments. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggs, B.L.; Khosla, S.; Melton, L.J., 3rd. Sex steroids and the construction and conservation of the adult skeleton. Endocr. Rev. 2002, 23, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, K.; Styrkarsdottir, U.; Evangelou, E.; Hsu, Y.H.; Duncan, E.L.; Ntzani, E.E.; Oei, L.; Albagha, O.M.E.; Amin, N.; Kemp, J.P.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 56 bone mineral density loci and reveals 14 loci associated with risk of fracture. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Calle, J.; Riancho, J.A. The role of DNA methylation in common skeletal disorders. Biology 2012, 1, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, E. Pathogenesis of bone fragility in women and men. Lancet 2002, 359, 1841–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanis, J.A.; Johansson, H.; Harvey, N.C.; McCloskey, E.V. A brief history of FRAX. Arch. Osteoporos. 2018, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, F.; Canalis, E. Management of endocrine disease: Secondary osteoporosis: Pathophysiology and management. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 173, R131–R151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosman, F.; de Beur, S.J.; LeBoff, M.S.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Tanner, B.; Randall, S.; Lindsay, R. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 2014, 25, 2359–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanis, J.A.; Harvey, N.C.; Johansson, H.; Odén, A.; Leslie, W.D.; McCloskey, E.V. FRAX update. J. Clin. Densitom. 2017, 20, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, B.C.; Leslie, W.D.; Resch, H.; Lamy, O.; Lesber, O.; Binkley, N.; McCloskey, E.V.; Kanis, J.A.; Bilezikian, J.P. Trabecular bone score: A noninvasive analytical method based upon the DXA image. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanis, J.A.; Johansson, H.; Harvey, N.C.; Gudnason, V.; Sigurdsson, G.; Siggeirsdottir, K.; Lorentzon, M.; Liu, E.; Vandenput, L.; McCloskey, E.V. Adjusting conventional FRAX estimates of fracture probability according to the recency of sentinel fractures. Osteoporos. Int. 2020, 31, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, N.C.; Glüer, C.C.; Binkley, N.; McCloskey, E.V.; Brandi, M.L.; Cooper, C.; Kendler, D.; Lamy, O.; Laslop, A.; Camargos, B.M.; et al. Trabecular bone score (TBS) as a new complementary approach for osteoporosis evaluation in clinical practice. Bone 2015, 78, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastell, R.; Rosen, C.J.; Black, D.M.; Cheung, A.M.; Murad, M.H.; Shoback, D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 1595–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schousboe, J.T.; Shepherd, J.A.; Bilezikian, J.P.; Baim, S. Executive summary of the 2013 ISCD Position Development Conference on bone densitometry. J. Clin. Densitom. 2013, 16, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2018, 319, 2521–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, P.M.; Petak, S.M.; Binkley, N.; Diab, D.L.; Elber, L.S.; Harris, S.T.; Hurley, D.L.; Kelly, J.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Pessah-Pollack, R.; et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis—2020 update. Endocr Pract. 2020, 26, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gourlay, M.L.; Fine, J.P.; Preisser, J.S.; May, R.C.; Li, C.; Lui, L.Y.; Ransohoff, D.F.; Cauley, J.A.; Ensrud, K.E. Bone-density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, G.M.; Fogelman, I. The role of DXA bone density scans in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis. Postgrad. Med. J. 2007, 83, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewiecki, E.M.; Binkley, N.; Bilezikian, J.P.; Kendler, D.L.; Leib, E.S.; Petak, S.M. Official positions of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry. J. Clin. Densitom. 2006, 9, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.E. Quantitative computed tomography. Eur. J. Radiol. 2009, 71, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanis, J.A.; Norton, N.; Harvey, N.C.; Jacobson, T.; Johansson, H.; Lorentzon, M.; McCloskey, E.V.; Willers, C.; Borgström, F. SCOPE 2021: A new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe. Arch Osteoporos. 2021, 16, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanis, J.A.; Harvey, N.C.; McCloskey, E.; Bruyère, O.; Veronese, N.; Lorentzon, M.; Cooper, C.; Rizzoli, R.; Adib, G.; Al-Daghri, N.; et al. Algorithm for the management of patients at low, high and very high risk of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos. Int. 2020, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, H.; Siggeirsdóttir, K.; Harvey, N.C.; Odén, A.; Gudnason, V.; McCloskey, E.; Sigurdsson, G.; Kanis, J.A. Imminent risk of fracture after fracture. Osteoporos. Int. 2017, 28, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoback, D.; Rosen, C.J.; Black, D.M.; Cheung, A.M.; Murad, M.H.; Eastell, R. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: An Endocrine Society guideline update. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosman, F.; Crittenden, D.B.; Adachi, J.D.; Binkley, N.; Czerwinski, E.; Ferrari, S.; Hofbauer, L.C.; Lau, E.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Miyauchi, A.; et al. Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1532–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Qin, S.X.; Wang, Q.Y.; Li, Y.F.; Qu, X.L.; Yue, C.; Hu, L.; Sheng, Z.F.; Wang, X.B.; Wan, X.M. Cost-effectiveness analysis of five drugs for treating postmenopausal women in the United States with osteoporosis and a very high fracture risk. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2023, 46, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, C.M.; Alexander, D.D.; Boushey, C.J.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Lappe, J.M.; LeBoff, M.S.; Liu, S.; Looker, A.C.; Wallace, T.C.; Wang, D.D. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and risk of fractures: An updated meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Speechley, M.; Ginter, S.F. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 319, 1701–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The timed ‘Up & Go’: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1991, 39, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Woolcott, J.C.; Richardson, K.J.; Wiens, M.O.; Patel, B.; Marin, J.; Khan, K.M.; Marra, C.A. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 1952–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, R.H.; Foss, A.J.; Osborn, F.; Gregson, R.M.; Zaman, A.; Masud, T. Falls and health status in elderly women following first eye cataract surgery: A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 89, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrington, C.; Fairhall, N.J.; Wallbank, G.K.; Tiedemann, A.; Michaleff, Z.A.; Howard, K.; Clemson, L.; Hopewell, S.; Lamb, S.E. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1, CD012424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, L.D.; Robertson, M.C.; Gillespie, W.J.; Sherrington, C.; Gates, S.; Clemson, L.M.; Lamb, S.E. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 2012, CD007146. [Google Scholar]

- Menant, J.C.; Steele, J.R.; Menz, H.B.; Munro, B.J.; Lord, S.R. Optimizing footwear for older people at risk of falls. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2008, 45, 1167–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibao, C.; Lipsitz, L.A.; Biaggioni, I. Evaluation and treatment of orthostatic hypotension. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2013, 7, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Staehelin, H.B.; Orav, J.E.; Stuck, A.E.; Theiler, R.; Wong, J.B.; Egli, A.; Kiel, D.P.; Henschkowski, J. Fall prevention with supplemental and active forms of vitamin D: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2009, 339, b3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Dodson, T.B.; Fantasia, J.; Goodday, R.; Aghaloo, T.; Mehrotra, B.; O’Ryan, F. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw—2014 update. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 1938–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Morrison, A.; Hanley, D.A.; Felsenberg, D.; McCauley, L.K.; O’Ryan, F.; Reid, I.R.; Ruggiero, S.L.; Taguchi, A.; Tetradis, S.; et al. Diagnosis and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw: A systematic review and international consensus. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 30, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, M.R.; Burr, D.B. The pathogenesis of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: So many hypotheses, so few data. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, I.R. Osteonecrosis of the jaw: Who gets it, and why? Bone 2009, 44, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedghizadeh, P.P.; Kumar, S.K.; Gorur, A.; Schaudinn, C.; Shuler, C.F.; Costerton, J.W. Identification of microbial biofilms in osteonecrosis of the jaws secondary to bisphosphonate therapy. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 66, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, F.; Brown, J.E.; Van Poznak, C.; Ibrahim, T.; Stemmer, S.M.; Stopeck, A.T.; Diel, I.J.; Takahashi, S.; Shore, N.; Henry, D.H.; et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of osteonecrosis of the jaw: Integrated analysis from three blinded active-controlled phase III trials in cancer patients with bone metastases. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 1341–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Morrison, A.; Kendler, D.L.; Rizzoli, R.; Hanley, D.A.; Felsenberg, D.; McCauley, L.K.; O’Ryan, F.; Reid, I.R.; Ruggiero, S.L.; et al. Case-based review of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) and application of the international recommendations for management from the International Task Force on ONJ. J. Clin. Densitom. 2017, 20, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, P.; Bedogni, G.; Bedogni, A.; Petrie, A.; Porter, S.; Campisi, G.; Fiorentino, S.; Toniolo, B.; Yarom, N.; Hooper, M.; et al. Time to onset of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: A multicentre retrospective cohort study. Oral Dis. 2017, 23, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleisher, K.E.; Kontio, R.; Otto, S. Antiresorptive drug-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (ARONJ)—A guide to research. Guideline of the ASBMR/AAOMS/ADA/IAOMS/IOF. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 2985–2994. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, S.; Pautke, C.; Van den Wyngaert, T.; Niepel, D.; Almirall, D. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Prevention, diagnosis and management in patients with cancer and bone metastases. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2018, 69, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellstein, J.W.; Adler, R.A.; Edwards, B.; Jacobsen, P.L.; Kalmar, J.R.; Koka, S.; Migliorati, C.A.; Ristic, H. Managing the care of patients receiving antiresorptive therapy for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2011, 142, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarom, N.; Shapiro, C.L.; Peterson, D.E.; Van Poznak, C.H.; Bohlke, K.; Ruggiero, S.L.; Migliorati, C.A.; Khan, A.; Morrison, A.; Anderson, H.; et al. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: MASCC/ISOO/ASCO clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2270–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasilakis, A.D.; Pepe, J.; Napoli, N.; Palermo, A.; Magopoulos, C.; Khan, A.A.; Zillikens, M.C.; Body, J.J. Osteonecrosis of the Jaw and Antiresorptive Agents in Benign and Malignant Diseases: A Critical Review Organized by the ECTS. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, 1441–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napeñas, J.J.; Kujan, O.; Arduino, P.G.; Sukumar, S.; Galvin, S.; Baričević, M.; Costella, J.; Czerninski, R.; Peterson, D.E.; Lockhart, P.B. World Workshop on Oral Medicine VI: Controversies regarding dental management of medically complex patients: Assessment of current recommendations. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2015, 120, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennardo, F.; Buffone, C.; Giudice, A. New therapeutic opportunities for COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab: Possible correlation of interleukin-6 receptor inhibitors with osteonecrosis of the jaws. Oral Oncol. 2020, 106, 104659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.M.; Rosen, C.J. Clinical practice. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, G.; Saag, K.G. Expert Perspective: How, When, and Why to Potentially Stop Antiresorptive Drugs in Osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2025, 77, 1294–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shane, E.; Burr, D.; Abrahamsen, B.; Adler, R.A.; Brown, T.D.; Cheung, A.M.; Cosman, F.; Curtis, J.R.; Dell, R.; Dempster, D.W.; et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: Second report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, D.M.; Geiger, E.J.; Eastell, R.; Vittinghoff, E.; Li, B.H.; Ryan, D.S.; Dell, R.M.; Adams, A.L. Atypical femur fracture risk versus fragility fracture prevention with bisphosphonates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, D.M.; Schwartz, A.V.; Ensrud, K.E.; Cauley, J.A.; Levis, S.; Quandt, S.A.; Satterfield, S.; Wallace, R.B.; Bauer, D.C.; Palermo, L.; et al. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment: The Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX): A randomized trial. JAMA 2006, 296, 2927–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, A.V.; Bauer, D.C.; Cummings, S.R.; Cauley, J.A.; Ensrud, K.E.; Palermo, L.; Wallace, R.B.; Hochberg, M.C.; Feldstein, A.C.; Lombardi, A.; et al. Efficacy of continued alendronate for fractures in women with and without prevalent vertebral fracture: The FLEX trial. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, K.N.; Brown, K.A.; Cheung, A.M.; Kim, S.; Gagnon, C.; Cadarette, S.M. Comparative fracture risk during osteoporosis drug holidays after long-term risedronate versus alendronate therapy: A propensity score-matched cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, J.R.; Saag, K.G.; Arora, T.; Wright, N.C.; Yun, H.; Daigle, S.; Kilgore, M.L.; Delzell, E. Duration of bisphosphonate drug holidays and associated fracture risk. Med. Care 2020, 58, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.M.; Abrahamsen, B.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Einhorn, T.; Napoli, N. Atypical femur fractures: Review of epidemiology, relationship to bisphosphonates, prevention, and clinical management. Endocr. Rev. 2019, 40, 333–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, J.; Tay, Y.K.D.; Shane, E. Current understanding of epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of atypical femur fractures. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2018, 16, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compston, J.; Cooper, A.; Cooper, C.; Gittoes, N.; Gregson, C.; Harvey, N.; Hope, S.; Kanis, J.A.; McCloskey, E.V.; Poole, K.E.S.; et al. UK clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Arch. Osteoporos. 2017, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewiecki, E.M.; Binkley, N.; Morgan, S.L.; Shuhart, C.R.; Camargos, B.M.; Carey, J.J.; Gordon, C.M.; Janber, E.I.; Kanis, J.A.; Kessenich, C.R.; et al. Best practices for dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry measurement and reporting: International Society for Clinical Densitometry guidance. J. Clin. Densitom. 2016, 19, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, H.G.; Bolognese, M.A.; Yuen, C.K.; Kendler, D.L.; Miller, P.D.; Yang, Y.C.; Grazette, L.; San Martin, J.; Gallagher, J.C. Effects of denosumab treatment and discontinuation on bone mineral density and bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Langdahl, B. Mechanisms underlying the long-term and withdrawal effects of denosumab therapy on bone. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2023, 19, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.R.; Ferrari, S.; Eastell, R.; Gilchrist, N.; Jensen, J.B.; McClung, M.; Roux, C.; Törring, O.; Valter, I.; Wang, A.T.; et al. Vertebral fractures after discontinuation of denosumab: A post hoc analysis of the randomized placebo-controlled FREEDOM trial and its extension. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2018, 33, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosman, F.; Huang, S.; McDermott, M.; Cummings, S.R. Multiple vertebral fractures after denosumab discontinuation: FREEDOM and FREEDOM extension trials additional post hoc analyses. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2022, 37, 2112–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsourdi, E.; Zillikens, M.C.; Meier, C.; Body, J.J.; Gonzalez Rodriguez, E.; Anastasilakis, A.D.; Abrahamsen, B.; McCloskey, E.; Hofbauer, L.C.; Guañabens, N.; et al. Fracture risk and management of discontinuation of denosumab therapy: A systematic review and position statement by ECTS. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 106, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leder, B.Z.; Tsai, J.N.; Uihlein, A.V.; Wallace, P.M.; Lee, H.; Neer, R.M.; Burnett-Bowie, S.A.M. Denosumab and teriparatide transitions in postmenopausal osteoporosis (the DATA-Switch study): Extension of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostis, P.; Paschou, S.A.; Mintziori, G.; Ceausu, I.; Depypere, H.; Lambrinoudaki, I.; Mueck, A.; Pérez-López, F.R.; Rees, M.; Senturk, L.M.; et al. Drug holidays from bisphosphonates and denosumab in postmenopausal osteoporosis: EMAS position statement. Maturitas 2017, 101, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsourdi, E.; Langdahl, B.; Cohen-Solal, M.; Aubry-Rozier, B.; Eriksen, E.F.; Guañabens, N.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B.; Ralston, S.H.; Eastell, R.; Zillikens, M.C. Discontinuation of denosumab therapy for osteoporosis: A systematic review and position statement by ECTS. Bone 2017, 105, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Couture, G.; Degboé, Y. Discontinuation of denosumab: Gradual decrease in doses preserves half of the bone mineral density gain at the lumbar spine. JBMR Plus 2023, 7, e10731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, H.G.; Wagman, R.B.; Brandi, M.L.; Brown, J.P.; Chapurlat, R.; Cummings, S.R.; Czerwiński, E.; Fahrleitner-Pammer, A.; Kendler, D.L.; Lippuner, K.; et al. 10 years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: Results from the phase 3 randomised FREEDOM trial and open-label extension. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, N.; Shin, S.; Kim, H.; Kang, S.; Rhee, Y. Romosozumab following denosumab improves lumbar spine bone mineral density and trabecular bone score greater than denosumab continuation in postmenopausal women. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2025, 40, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Liu, C.Y.; Wu, Y.K.; Kuo, L.T. Zoledronate sequential therapy after denosumab discontinuation to prevent bone mineral density reduction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2443899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, G.; Ghielmetti, A.; Zampogna, M.; Chiodini, I.; Arosio, M.; Persani, L. Zoledronate after denosumab discontinuation: Is repeated administration more effective than single infusion? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, e1817–e1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosman, F.; Oates, M.; Betah, D.; Eriksen, E.F.; Ferrari, S.; Gilchrist, N.; Langdahl, B.; Morales Torres, J.; Saag, K.; Kendler, D.L. Romosozumab followed by denosumab versus denosumab only: A post hoc analysis of FRAME and FRAME extension. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2024, 39, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Gild, M.L.; McDonald, M.M.; Baldock, P.A.; Center, J.R.; Eisman, J.A. A novel sequential treatment approach between denosumab and romosozumab in patients with severe osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 2024, 35, 1669–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, S.; Hofbauer, L.C. Osteoporosis treatment: Recent developments and ongoing challenges. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 898–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| HISTORY | |

| Fracture History | • Prior fragility fractures (location, age, mechanism) • Recent fractures (<24 months) indicating imminent risk • Childhood fractures or recurrent fractures • Fractures at atypical sites or with minimal trauma |

| Family History | • Parental hip fracture (strong FRAX risk factor) • Osteoporosis in first-degree relatives • Kyphosis or height loss in parents • Osteogenesis imperfecta or other genetic bone disorders |

| Menstrual/Reproductive History | • Age at menarche and menopause • Early menopause (<45 years) or surgical menopause • Prolonged amenorrhea (>12 months premenopausal) • History of eating disorders or female athlete triad • Hormone replacement therapy use (type, duration) |

| Medications | • Glucocorticoids (dose, duration; ≥5mg/day for ≥3 months) • Aromatase inhibitors (breast cancer treatment) • Anticonvulsants (phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine) • Proton pump inhibitors (long-term use) • Thyroid hormone (excess replacement) • GnRH agonists, medroxyprogesterone, heparin (long-term) • Prior osteoporosis treatment (agent, duration, response) |

| Lifestyle Factors | • Smoking status (current, former, pack-years) • Alcohol intake (≥3 units/day is FRAX risk factor) • Physical activity level and weight-bearing exercise • Calcium intake (dietary + supplements) • Vitamin D sources (sun exposure, diet, supplements) • Immobilization or sedentary lifestyle |

| Medical Conditions | • Rheumatoid arthritis (independent FRAX risk factor) • Other inflammatory conditions (SLE, IBD, ankylosing spondylitis) • Endocrine disorders (hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, Cushing) • Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes mellitus • Chronic kidney disease (stage, on dialysis?) • Malabsorption (celiac disease, gastric bypass, IBD) • Chronic liver disease • COPD and other chronic pulmonary disease • HIV infection • Malignancy (myeloma, breast/prostate cancer, bone metastases) |

| Fall Risk Assessment | • Falls in the past 12 months (number, circumstances) • Balance and gait problems • Visual impairment • Neurological conditions (stroke, Parkinson, neuropathy) • Medications affecting balance (sedatives, antihypertensives) • Home hazards and footwear |

| Dental History | • Current dental health status • Planned dental procedures (extractions, implants) • History of periodontal disease • Denture use and fit |

| PHYSICAL EXAMINATION | |

| Anthropometrics | • Current height (compare to historical maximum) • Height loss > 4 cm historical or >2 cm prospective → vertebral imaging • Weight and BMI (<20 kg/m2 is risk factor) • Recent unintentional weight loss |

| Spine Examination | • Thoracic kyphosis (dowager’s hump) • Rib-pelvis distance (<2 fingerbreadths suggests vertebral fracture) • Occiput-to-wall distance (>0 cm suggests kyphosis) • Spinal tenderness (may indicate acute fracture) |

| Musculoskeletal | • Muscle mass and strength (sarcopenia assessment) • Joint deformities suggesting inflammatory arthritis • Thigh or groin pain (may indicate atypical femoral fracture) |

| Balance and Mobility | • Timed Up and Go test (>12 s indicates fall risk) • Tandem stand and single leg stance • Gait assessment (speed, stability, use of assistive devices) |

| Signs of Secondary Causes | • Cushingoid features (moon facies, striae, buffalo hump) • Thyroid enlargement or signs of hyperthyroidism • Blue sclerae (osteogenesis imperfecta) • Signs of malabsorption or chronic disease |

| INVESTIGATIONS | |

| Baseline Laboratory (All Patients) | • Complete blood count • Serum calcium, phosphate, albumin • Alkaline phosphatase (bone-specific if available) • Creatinine and eGFR • 25-hydroxyvitamin D • TSH |

| Additional Tests (Based on Clinical Suspicion) | • PTH (if calcium abnormal or CKD) • Serum protein electrophoresis (if myeloma suspected) • 24 h urinary calcium (hypercalciuria, malabsorption) • Celiac serology (TTG-IgA) • Testosterone (men), FSH/LH (premenopausal women) • 24 h urinary free cortisol (if Cushing suspected) • Bone turnover markers (CTX, P1NP) for monitoring |

| Imaging | • DXA of lumbar spine, hip, and 33% radius • Vertebral fracture assessment (VFA) or lateral spine X-ray • Trabecular bone score (TBS) if available • Spine MRI if acute fracture or malignancy suspected |

| Risk Assessment Tools | • FRAX score (with and without BMD) • Apply FRAX adjustments if needed (TBS, glucocorticoid dose) • Compare to country-specific intervention thresholds |

| Universal Screening Indications |

| • All women aged ≥ 65 years • All men aged ≥ 70 years |

| Postmenopausal Women <65 Years: Screen if ANY of the Following Present |

| • Prior fragility fracture (after age 50) • Parental history of hip fracture • Low body weight (<58 kg) or BMI < 20 kg/m2 • Current smoking • Excess alcohol intake (≥3 units/day) • Rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory arthritis • Early menopause (<45 years) or prolonged premenopausal amenorrhea • FRAX 10-year major osteoporotic fracture probability ≥ 10% (without BMD) |

| Medical Conditions and Medications Warranting DXA |

| • Glucocorticoid therapy: ≥5 mg prednisone equivalent daily for ≥3 months (current or planned) • Aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer • Androgen deprivation therapy (in men) • Primary hyperparathyroidism • Hyperthyroidism or excessive thyroid hormone replacement • Hypogonadism or premature ovarian insufficiency • Malabsorption syndromes (celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, gastric bypass) • Chronic kidney disease (CKD-MBD assessment) • Chronic liver disease • Organ transplantation • Type 1 diabetes mellitus • Anorexia nervosa or severe malnutrition • HIV infection (particularly with antiretroviral therapy) |

| Radiographic or Clinical Findings Warranting DXA |

| • Vertebral fracture or deformity on imaging (incidental or symptomatic) • Height loss > 4 cm (historical) or >2 cm (prospective) • Kyphosis suggesting vertebral fracture • Radiographic osteopenia on any imaging study |

| Monitoring Indications |

| • Monitoring response to osteoporosis treatment (typically every 1–2 years initially) • Monitoring bone loss during drug holiday • Detecting bone loss in untreated patients with osteopenia (every 2–5 years based on baseline) |

| Agent | Mechanism | Dose/Route | Fracture Reduction | Advantages | Limitations | Special Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alendronate | Antiresorptive (BP) | 70 mg PO weekly | VF 44%, NVF 25%, HF 40% | Extensive data; Low cost; Generic | GI effects; Complex dosing | Avoid CrCl < 35; Drug holiday OK |

| Zoledronic Acid | Antiresorptive (BP) | 5 mg IV yearly | VF 70%, NVF 25%, HF 41% | Annual; No GI; Best adherence | Acute phase rxn; IV access | Post-hip Fx proven; Longest holiday |

| Denosumab | Anti-RANKL | 60 mg SC q6mo | VF 68%, NVF 20%, HF 40% | OK in CKD; Progressive gains | Rebound if stopped; Hypocalcemia | MUST transition to BP if stopping |

| Teriparatide | Anabolic (PTH) | 20 μg SC daily × 24 mo | VF 65%, NVF 35% | Builds bone; Best for severe | Daily inj; Cost; 24 mo limit | MUST follow with AR; CV safe |

| Romosozumab | Anti-sclerostin | 210 mg SC monthly × 12 mo | VF 73%, CF 36% | Fastest BMD gain; Dual effect | CV signal; 12 mo limit; Cost | CI if prior MI/stroke; MUST follow AR |

| Intervention | Key Components | Expected Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Exercise Programs | Balance training, strength training, Tai Chi, gait training; supervised initially; sustained participation | ↓ Falls 20–40%; Tai Chi ↓ 40–50% |

| Medication Review | Reduce polypharmacy; minimize sedatives, hypnotics, antihypertensives causing orthostasis; time diuretics appropriately | ↓ Falls 20–30% with psychotropic withdrawal |

| Vision Correction | Annual eye exam; cataract surgery when indicated; single-vision glasses for mobility; optimize home lighting | ↓ Falls with cataract surgery; single-vision glasses ↓ outdoor falls |

| Home Safety Modification | Remove loose rugs; install grab bars, handrails; improve lighting; clear pathways; non-slip mats in bathrooms | ↓ Falls 20–30% (especially with OT assessment) |

| Footwear Optimization | Low heels (<2.5 cm); firm heel counter; slip-resistant soles; secure fastening; avoid slippers, bare feet | Reduces fall risk; limited direct trial evidence |

| Orthostatic Hypotension Management | Slow positional changes; adequate hydration; compression stockings; medication adjustment; fludrocortisone if refractory | Reduces syncope and falls; individual response variable |

| Vitamin D Supplementation | 700–1000 IU daily; target 25(OH)D > 60 nmol/L; avoid annual bolus dosing | ↓ Falls 14–20% (greater if deficient at baseline) |

| Hip Protectors | Padded undergarments deflecting impact from greater trochanter; best evidence in nursing home residents | ↓ Hip fractures in institutions if worn; poor adherence limits effectiveness |

| Multifactorial Assessment | Comprehensive geriatric assessment addressing multiple risk factors simultaneously; individualized intervention plan | ↓ Falls 20–30%; most effective approach for high-risk individuals |

| Clinical Scenario | Approximate Risk |

|---|---|

| MRONJ Risk by Treatment Setting | |

| Oral bisphosphonates for osteoporosis | 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 100,000 per year |

| IV zoledronic acid 5 mg yearly (osteoporosis) | 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 50,000 per year |

| Denosumab 60 mg q6mo (osteoporosis) | 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 100,000 per year |

| IV zoledronic acid 4 mg monthly (cancer) | 1–2% (1 in 50 to 1 in 100) |

| Denosumab 120 mg monthly (cancer) | 1–5% (1 in 20 to 1 in 100) |

| Comparative Common Medical Risks | |

| GI bleeding from low-dose aspirin | 1 in 1000 per year |

| VTE from oral contraceptives | 1 in 1000 per year |

| Background ONJ (no bone medications) | ~1 in 100,000 per year |

| Risks of NOT Treating Osteoporosis | |

| Lifetime hip fracture risk (women age 50) | 1 in 6 (17%) |

| One-year mortality after hip fracture | 20–25% |

| Lifetime any osteoporotic fracture risk (women) | 1 in 2 (50%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ena, G.; Soyfoo, M. Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: From Molecular Pathways to Therapeutic Targets—A Mechanism-to-Practice Framework Integrating Pharmacotherapy, Fall Prevention, and Adherence into Patient-Centered Care. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010102

Ena G, Soyfoo M. Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: From Molecular Pathways to Therapeutic Targets—A Mechanism-to-Practice Framework Integrating Pharmacotherapy, Fall Prevention, and Adherence into Patient-Centered Care. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleEna, Graziella, and Muhammad Soyfoo. 2026. "Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: From Molecular Pathways to Therapeutic Targets—A Mechanism-to-Practice Framework Integrating Pharmacotherapy, Fall Prevention, and Adherence into Patient-Centered Care" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010102

APA StyleEna, G., & Soyfoo, M. (2026). Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: From Molecular Pathways to Therapeutic Targets—A Mechanism-to-Practice Framework Integrating Pharmacotherapy, Fall Prevention, and Adherence into Patient-Centered Care. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010102