Risk Factors for Prenatal Anxiety in European Women: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Strategy for the Selection of Studies and Analysis of Results

3. Results

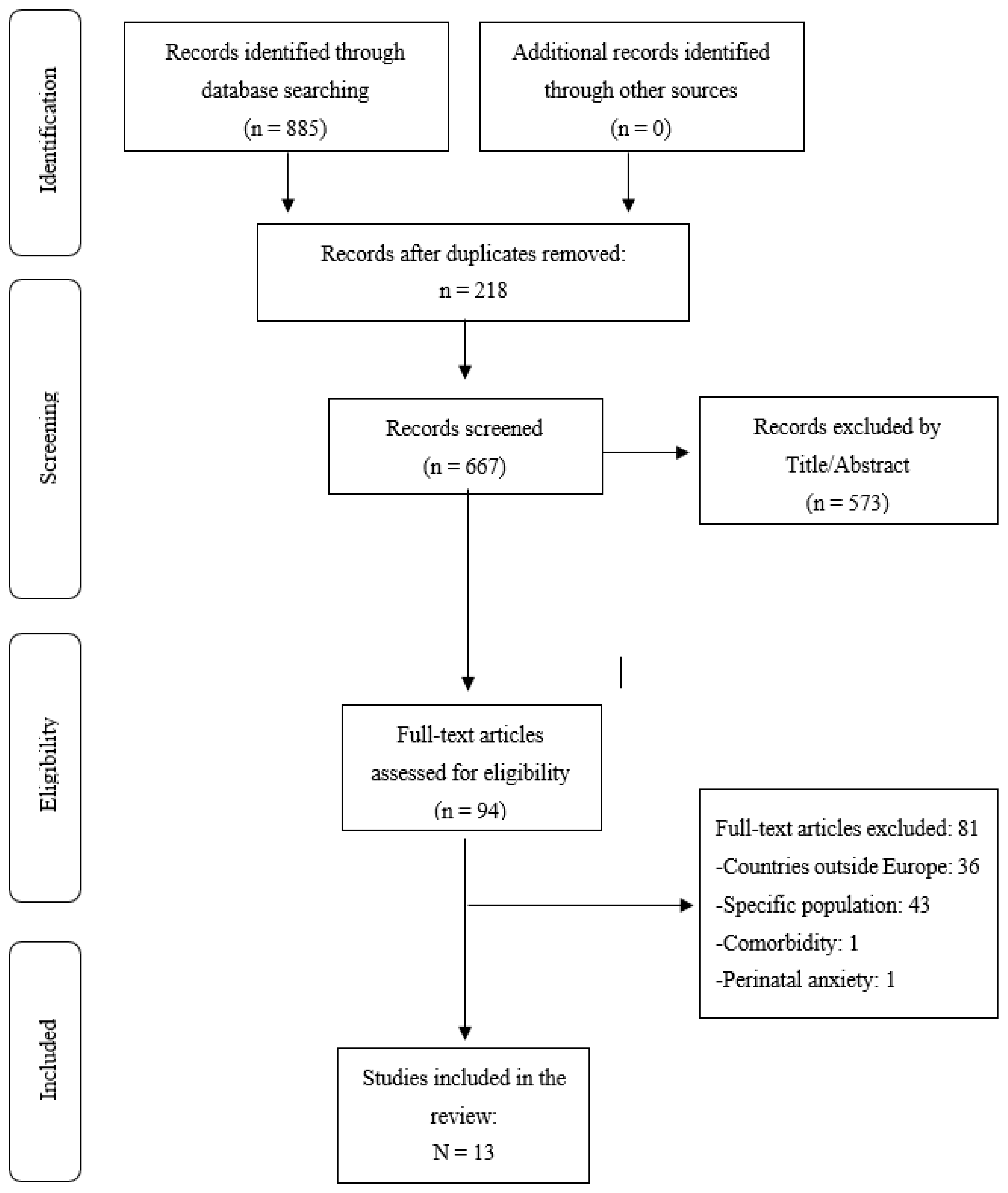

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Selected Studies

| Study | Anxiety Measures | Sample Size (n) | Study Design | Regression Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martini et al. (2015) Germany [45] | CIDI-V | 306 | Longitudinal Prospective | Not specified |

| Podvornik et al. (2015) Slovenia [49] | STAI ≥ 45 | 348 | Cross-sectional (1st, 2nd and 3rd T) | Bivariate |

| van de Loo et al. (2018) Netherlands [39] | HADS-A ≥ 8 | 2897 | Longitudinal | Multivariate |

| Soto-Balbuena et al. (2018) Spain [15] | GAD-7 ≥ 7 | 932 | Longitudinal | Not specified |

| Sharapova et al. (2018) Switzerland [38] | STAI-S ≥ 45 | 84 | Cohort (3rd T) | Multivariate |

| Osnes et al. (2019) Norway [50] | SCL-A ≥ 18 | 1563 | Cross-sectional (2nd y 3rd T) | Multivariate |

| González-Mesa et al. (2019) Spain [37] | STAI > 45 | 514 | Cohort (1st T) | Bivariate and Multivariate |

| Cena et al. (2020) Italy [44] | STAI-S ≥ 40 | 1143 | Cross-sectional (2nd y 3rd T) | Bivariate and Multivariate |

| Insan et al. (2020) United Kingdom [41] | GHQ > 6 | 7824 | Cohort (2nd T) | Multivariate |

| Savory et al. (2021) United Kingdom [42] | GAD-7 ≥ 10 | 302 | Cohorts (1st T) | Multivariate |

| Koyucu et al. (2021) United Kingdom [48] | DASS | 729 | Cross-sectional Pregnancy | Multivariate |

| Filippetti et al. (2022) United Kingdom [40] | STAI-S ≥ 40 | 150 | Cross-sectional Pregnancy | Multivariate |

| Răchită et al. (2023) Romania [47] | HADS-A > 11 HAMA > 20 | 215 | Cross-sectional (3rd T) | Multivariate |

| Authors and Country | Sociodemographic Variables | Obstetric Variables | Psychological Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Martini et al. (2015) Germany [45] | Unsatisfactory relationship *1 0.98 | -History of anxiety and/or depression *1 14.31/1.79 -Experiencing trauma and/or sexual trauma *1 3.15/2.96 -Low self-esteem *1 0.89 -Low social support *1 0.44 | |

| Podvornik et al. (2015) Slovenia [49] | Lower income level (state and trait) r 0.12/0.22 Lower educational level (trait) r 0.19 | ||

| van de Loo et al. (2018) Netherlands [39] | Age < 30 -yr-old *1 0.50 Not living with a partner *1 1.12 Low or medium educational level * | Took > 12 months to get pregnant *1 0.57 Infections during pregnancy *1 0.22 Extreme fatigue *1 0.35 | Previous depression *1 0.92 Negative life events *1 1.49 Family with a history of depression *1 0.59 |

| Soto-Balbuena et al. (2018) Spain [15] | Financial problems *1 0.20 (2nd T) | -Changes in social relationships *1 0.15–0.25 (all trimesters) -Stressful life events *1 0.17 (1st T) | |

| Sharapova et al. (2018) Switzerland [38] Immigrant women Native women | Socioeconomic status of the couple (low) *1 0.30 | Primiparity *1 0.33 | Trait anxiety *1 0.59 Lack of satisfaction with marital support *1 0.29 Trait anxiety *1 0.73 |

| Osnes et al. (2019) Norway [50] | Insomnia *1 0.42 | ||

| González-Mesa et al. (2019) Spain [37] Spanish women Turkish women | Lower educational level (state) *1 0.23 Religion (state and trait) *1 0.31–0.26 Unemployment (state) *1 0.10 | Increased number of children (state) *1 0.17 Used assisted reproduction techniques *1 0.15 (trait) | Low partner support (state and trait) *1 0.21–0.17 Lack of interest from the couple in the pregnancy (state and trait) *1 0.20–0.72 |

| Cena et al. (2020) Italy [44] | Lower educational level * (<0.01) Unemployment* (<0.01) Economic difficulties* (<0.01) | Unplanned pregnancy * (<0.01) No use of assisted reproduction techniques * (<0.05) Abortion history * (<0.05) Multiparity * (<0.05) | |

| Insan et al. (2020) United Kingdom [41] | |||

| British sample | No risk factors were found for the British sample. | ||

| Asian sample | Older age *1 0.12 Lower educational level *1 0.65 | ||

| Savory et al. (2021) United Kingdom [42] | Previous psychiatric disorders *1 3.95 Low self-efficacy *1 1.27 Low family support *1 1.13 | ||

| Koyucu et al. (2021) United Kingdom [48] | Unemployment *1 0.16 | -Pregnancy Risks*1 2.09 | Less social support *1 0.92 |

| Filippetti et al. (2022) United Kingdom [40] | COVID-19 pandemic * [0.40, 0.69] | ||

| Răchită et al. (2023) Romania [47] | Live in an urban area *1 1.84 | ||

3.3. Risk Factors for Prenatal Anxiety

3.3.1. Sociodemographic Risk Factors

3.3.2. Obstetric and/or Pregnancy-Related Risk Factors

3.3.3. Psychological Risk Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dunkel-Schetter, C. Psychological science on pregnancy: Stress processes, biopsychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2011, 62, 531–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadfield, K.; Akyirem, S.; Sartori, L.; Abdul-Latif, A.M.; Akaateba, D.; Bayrampour, H.; Daly, A.; Hadfield, K.; Abiiro, G.A. Measurement of pregnancy-related anxiety worldwide: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.V.; Shao, L.; Howell, H.; Lin, H.; Yonkers, K.A. Perinatal depression and birth outcomes in a Healthy Start project. Matern. Child. Health J. 2011, 15, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampaka, D.; Papatheodorou, S.I.; AlSeaidan, M.; Al Wotayan, R.; Wright, R.J.; Buring, J.E.; Dockery, D.W.; Christophi, C.A. Depressive symptoms and comorbid problems in pregnancy-results from a population based study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 112, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Lu, Z.; Hu, D.; Zhong, X. Influencing factors for prenatal stress, anxiety and depression in early pregnancy among women in Chongqing, China. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 253, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, H.A.; Einarson, A.; Taddio, A.; Koren, G.; Einarson, T.R. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: Systematic review. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 103, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, S.M. Depression during pregnancy: Rates, risks and consequences. J. Popul. Ther. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 16, e15–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, A.; Muhajarine, N. Prevalence of antenatal depression in women enrolled in an outreach program in Canada. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2006, 35, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posternak, M.A.; Zimmerman, M. Symptoms of atypical depression. Psychiatry Res. 2001, 104, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.M.; Lam, S.K.; Sze Mun Lau, S.M.; Chong, C.S.; Chui, H.W.; Fong, D.Y. Prevalence, course, and risk factors for antenatal anxiety and depression. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 110, 1102–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, C.; Ossola, P.; Amerio, A.; Daniel, B.D.; Tonna, M.; De Panfilis, C. Clinical management of perinatal anxiety disorders: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 190, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R.; Dennis, C.L. The prevalence of antenatal and postnatal co-morbid anxiety and depression: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 2041–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, C.-L.; Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 210, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinesi, A.; Maxwell, M.; O’Carroll, R.; Cheyne, H. Anxiety scales used in pregnancy: Systematic review. BJPsych Open 2019, 5, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Balbuena, C.; Rodríguez, M.F.; Escudero Gomis, A.I.; Ferrer Barriendos, F.J.; Le, H.N.; Pmb-Huca, G. Incidence, prevalence and risk factors related to anxiety symptoms during pregnancy. Psicothema 2018, 30, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val, A.; Míguez, M.C. Prevalence of antenatal anxiety in European women: A literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.H.; Tyer-Viola, L. Detection, treatment, and referral of perinatal depression and anxiety by obstetrical providers. J. Womens Health 2010, 19, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, N.; Nazir, H.; Zafar, S.; Chaudhri, R.; Atiq, M.; Mullany, L.C.; Rowther, A.A.; Malik, A.; Surkan, P.J.; Rahman, A. Development of a Psychological Intervention to Address Anxiety During Pregnancy in a Low-Income Country. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnan, S.A.; Wallace, M.; Joubert, A.E.; Haskelberg, H.; Andrews, G.; Newby, J.M. A systematic review of psychological treatments for clinical anxiety during the perinatal period. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2018, 21, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Míguez, M.C.; Fernández, V.; Pereira, B. Depresión postparto y factores asociados en mujeres con embarazos de riesgo [Postpartum depression and associated risk factors among women with risk pregnancies]. Behav. Psychol. 2017, 25, 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Alipour, Z.; Lamyian, M.; Hajizadeh, E. Anxiety and fear of childbirth as predictors of postnatal depression in nulliparous women. Women Birth 2012, 25, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré-Sender, B.; Torres, A.; Gelabert, E.; Andrés, S.; Roca, A.; Lasheras, G.; Valdés, M.; Garcia-Esteve, L. Mother-infant bonding in the postpartum period: Assessment of the impact of pre-delivery factors in a clinical sample. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2018, 21, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, T. Prenatal anxiety effects: A review. Infant. Behav. Dev. 2017, 49, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.-X.; Wu, Y.-L.; Xu, S.-J.; Zhu, R.-P.; Jia, X.-M.; Zhang, S.-F.; Huang, K.; Zhu, P.; Hao, J.-H.; Tao, F.-B. Maternal anxiety during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 159, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, S.E.; Puente, G.C.; Atencio, G.; Qiu, C.; Yanez, D.; Gelaye, B.; Williams, M.A. Risk of spontaneous preterm birth in relation to maternal depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms. J. Reprod. Med. 2013, 58, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Faisal-Cury, A.; Levy, R.B.; Azeredo, C.M.; Matijasevich, A. Prevalence and associated risk factors of prenatal depression underdiagnosis: A population-based study. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 153, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Míguez, M.C.; Vázquez, M.B. Prevalence of Depression during Pregnancy in Spanish Women: Trajectory and risk factors in each trimester. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accortt, E.E.; Cheadle, A.C.; Dunkel Schetter, C. Prenatal depression and adverse birth outcomes: An updated systematic review. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 1306–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T. Prenatal Depression Risk Factors, Developmental Effects and Interventions: A Review. J. Pregnancy Child Health 2017, 4, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Míguez, M.C.; Vázquez, M.B. Risk factors for antenatal depression: A review. World J. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnan, S.A.; Butler, C.; Sie, A.A.; Grierson, A.B.; Chen, A.Z.; Hobbs, M.J.; Joubert, A.E.; Haskelberg, H.; Mahoney, A.; Holt, C.; et al. A randomised controlled trial of ‘MUMentum postnatal’: Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety and depression in postpartum women. Behav. Res. Ther. 2019, 116, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, J.H.; Chenausky, K.L.; Freeman, M.P. Anxiety disorders during pregnancy: A systematic review. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, e1153–e1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayrampour, H.; Vinturache, A.; Hetherington, E.; Lorenzetti, D.L.; Tough, S. Risk factors for antenatal anxiety: A systematic review of the literature. J. Reprod. Infant. Psychol. 2018, 36, 476–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T. Postnatal anxiety prevalence, predictors and effects on development: A narrative review. Infant. Behav. Dev. 2018, 51, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mesa, E.; Kabukcuoglu, K.; Körükcü, O.; Blasco, M.; Ibrahim, N.; Cazorla-Granados, O.; Kavas, T. Correlates for state and trait anxiety in a multicultural sample of Turkish and Spanish women at first trimester of pregnancy. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 249, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharapova, A.; Goguikian Ratcliff, B. Psychosocial and sociocultural factors influencing antenatal anxiety and depression in non-precarious migrant women. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Loo, K.; Vlenterie, R.; Nikkels, S.J.; Merkus, P.; Roukema, J.; Verhaak, C.M.; Roeleveld, N.; van Gelder, M. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: The influence of maternal characteristics. Birth 2018, 45, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippetti, M.L.; Clarke, A.D.F.; Rigato, S. The mental health crisis of expectant women in the UK: Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on prenatal mental health, antenatal attachment and social support. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insan, N.; Slack, E.; Heslehurst, N.; Rankin, J. Antenatal depression and anxiety and early pregnancy BMI among White British and South Asian women: Retrospective analysis of data from the Born in Bradford cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savory, N.A.; Hannigan, B.; John, R.M.; Sanders, J.; Garay, S.M. Prevalence and predictors of poor mental health among pregnant women in Wales using a cross-sectional survey. Midwifery 2021, 103, 103103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Version 2018. McGill University. 2018. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Cena, L.; Mirabella, F.; Palumbo, G.; Gigantesco, A.; Trainini, A.; Stefana, A. Prevalence of maternal antenatal anxiety and its association with demographic and socioeconomic factors: A multicentre study in Italy. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, E84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, J.; Petzoldt, J.; Einsle, F.; Beesdo-Baum, K.; Höfler, M.; Wittchen, H.U. Risk factors and course patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders during pregnancy and after delivery: A prospective-longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 175, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankner, R.; Goldberg, R.P.; Fisch, R.Z.; Crum, R.M. Cultural elements of postpartum depression. A study of 327 Jewish Jerusalem women. J. Reprod. Med. 2000, 45, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Răchită, A.I.C.; Strete, G.E.; Sălcudean, A.; Ghiga, D.V.; Rădulescu, F.; Călinescu, M.; Nan, A.G.; Sasu, A.B.; Suciu, L.M.; Mărginean, C. Prevalence and risk factors of depression and anxiety among women in the last trimester of pregnancy: A cross-sectional study. Medicina 2023, 59, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyucu, R.G.; Karaca, P.P. The COVID-19 outbreak: Maternal Mental Health and Associated Factors. Midwifery 2021, 99, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podvornik, N.; Globevnik Velikonja, V.; Praper, P. Depression and anxiety in women during pregnancy in Slovenia. Zdr. Varst. 2015, 54, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osnes, R.S.; Roaldset, J.O.; Follestad, T.; Eberhard-Gran, M. Insomnia late in pregnancy is associated with perinatal anxiety: A longitudinal cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 248, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, S.R.M.; Ismail, A.S.; Samsudin, S.; Hassan, N.A.; Wh, W.M. Prevalence and factors associated with the depressive and anxiety symptoms amongst antenatal women. IIUM Med. J. Malays. 2021, 20, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrampour, H.; McDonald, S.; Tough, S. Risk factors of transient and persistent anxiety during pregnancy. Midwifery 2015, 31, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreen, H.E.; Kabir, Z.N.; Forsell, Y.; Edhborg, M. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy: A population based study in rural Bangladesh. BMC Womens Health 2011, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, J.; Cabral de Mello, M.; Patel, V.; Rahman, A.; Tran, T.; Holton, S.; Holmes, W. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2012, 90, 139G–149G. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bina, R. The impact of cultural factors upon postpartum depression: A literature review. Health Care Women Int. 2008, 29, 568–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.H.; Al Khedair, K.; Al-Jeheiman, R.; Al-Turki, H.A.; Al Qahtani, N.H. Anxiety and depression during pregnancy in women attending clinics in a University Hospital in Eastern province of Saudi Arabia: Prevalence and associated factors. Int. J. Womens Health 2018, 10, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardinelli, L.; Innocenti, A.; Benni, L.; Stefanini, M.C.; Lino, G.; Lunardi, C.; Svelto, V.; Afshar, S.; Bovani, R.; Castellini, G.; et al. Depression and anxiety in perinatal period: Prevalence and risk factors in an Italian sample. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2012, 15, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, A.; Raza, N.; Lodhi, H.W.; Muhammad, Z.; Jamal, M.; Rehman, A. Psychosocial factors of antenatal anxiety and depression in Pakistan: Is social support a mediator? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.X.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Ablat, A. The prevalence and related risk factors of anxiety and depression symptoms among Chinese pregnant women in Shanghai. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2009, 49, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, J.; Escoto-Lloyd, S. Health-related problems in a vulnerable population: Pregnant teens and adolescent mothers. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 1999, 34, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkel-Schetter, C.; Niles, A.N.; Guardino, C.M.; Khaled, M.; Kramer, M.S. Demographic, medical, and psychosocial predictors of pregnancy anxiety. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2016, 30, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.S.; Azam, I.S.; Ali, B.S.; Tabbusum, G.; Moin, S.S. Frequency and associated factors for anxiety and depression in pregnant women: A hospital-based cross-sectional study. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 653098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary-Goldman, J.; Malone, F.D.; Vidaver, J.; Ball, R.H.; Nyberg, D.A.; Comstock, C.H.; Saade, G.R.; Eddleman, K.A.; Klugman, S.; Dugoff, L.; et al. Impact of maternal age on obstetric outcome. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 105, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treacy, A.; Robson, M.; O’Herlihy, C. Dystocia increases with advancing maternal age. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 195, 760–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juarez Padilla, J.; Lara-Cinisomo, S.; Navarrete, L.; Lara, M.A. Perinatal anxiety symptoms: Rates and risk factors in Mexican women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umuziga, M.P.; Adejumo, O.; Hynie, M. A cross-sectional study of the prevalence and factors associated with symptoms of perinatal depression and anxiety in Rwanda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.T.; Yao, Y.; Dou, J.; Guo, X.; Li, S.Y.; Zhao, C.N.; Han, H.-Z.; Li, B. Prevalence and risk factors of maternal anxiety in late pregnancy in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naja, S.; Al Kubaisi, N.; Singh, R.; Bougmiza, I. Generalized and pregnancy-related anxiety prevalence and predictors among pregnant women attending primary health care in Qatar, 2018––2019. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal-Cury, A.; Rossi Menezes, P. Prevalence of anxiety and depression during pregnancy in a private setting sample. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2007, 10, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, M.; Chow, C.H.T.; Owais, S.; Frey, B.N.; Van Lieshout, R.J. Risk factors of new onset anxiety and anxiety exacerbation in the perinatal period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 238, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Gill, G.; Sikka, P.; Nehra, R. Antenatal depression and anxiety in Indian women: A systematic review. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2023, 32, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cankorur, V.S.; Abas, M.; Berksun, O.; Stewart, R. Social support and the incidence and persistence of depression between antenatal and postnatal examinations in Turkey: A cohort study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val, A.; Míguez, M.C. Telepsychological intervention for preventing anxiety: A study protocol. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anxiety | Depression | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factors | ||

| Lower educational level | V | V |

| Socioeconomic status | V | V |

| Obstetric factors | ||

| Unplanned pregnancy | V | |

| Complications and/or risks during pregnancy | V | |

| Psychological factors | ||

| History of psychological disorders | V | V |

| Prenatal depression | V | |

| Presence anxiety | V | |

| Exposure to adverse life events | V | V |

| Low social support | V | V |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Val, A.; Posse, C.M.; Míguez, M.C. Risk Factors for Prenatal Anxiety in European Women: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3248. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093248

Val A, Posse CM, Míguez MC. Risk Factors for Prenatal Anxiety in European Women: A Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(9):3248. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093248

Chicago/Turabian StyleVal, Alba, Cristina M. Posse, and M. Carmen Míguez. 2025. "Risk Factors for Prenatal Anxiety in European Women: A Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 9: 3248. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093248

APA StyleVal, A., Posse, C. M., & Míguez, M. C. (2025). Risk Factors for Prenatal Anxiety in European Women: A Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(9), 3248. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093248