The Use of Buccal Fat Pad Versus Buccal Mucosal Flap in Cleft Patient Palatoplasty—A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Anatomical and Physiological Considerations

1.2. Surgical Techniques and Outcomes

1.3. Patient Outcomes and Quality of Life

1.4. Complication Management After Cleft Palate Surgery

1.5. Buccal Fat Pad or Buccal Mucosal Flap

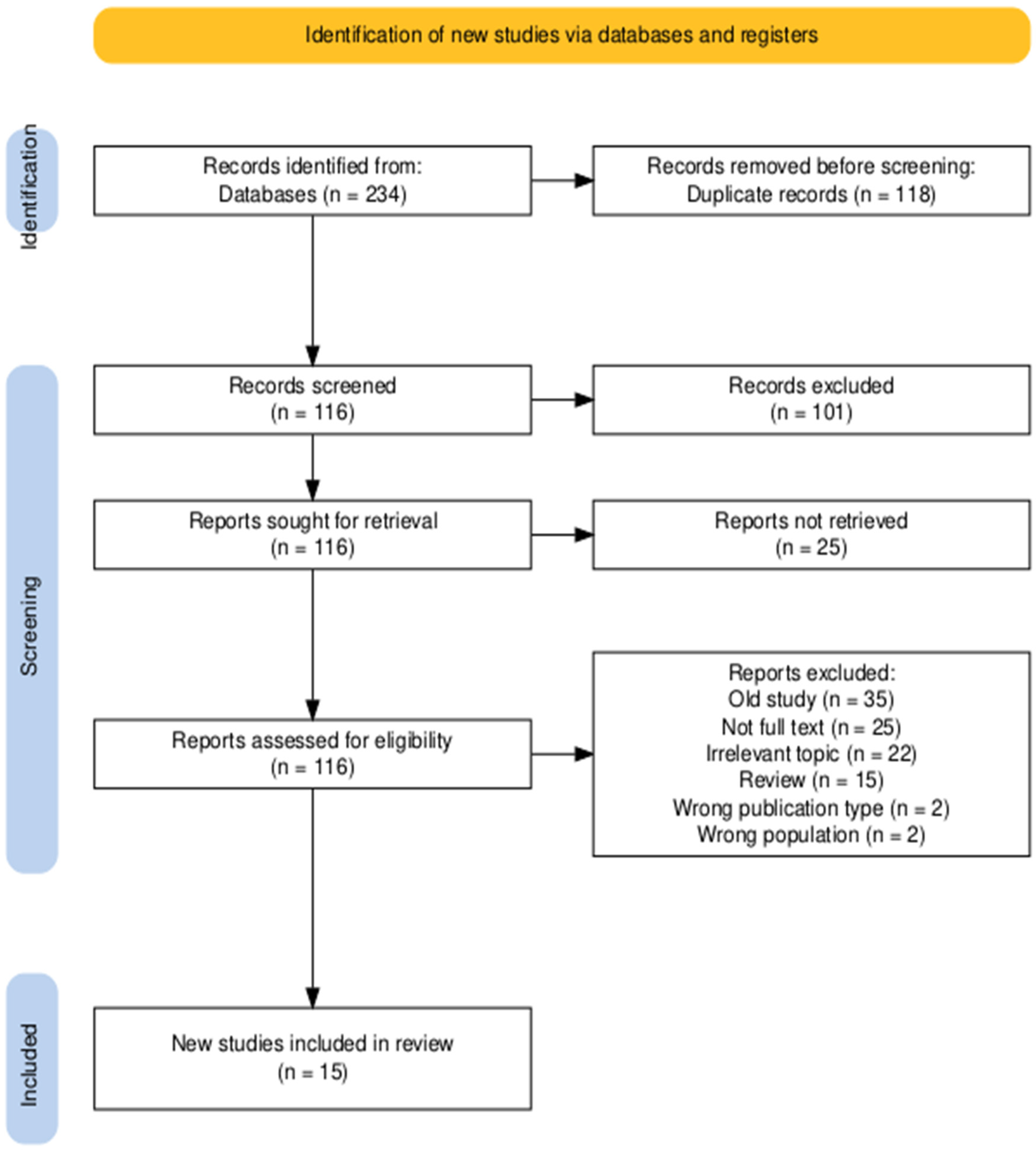

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BFP | Buccal Fat Pad |

| BMMF | Buccal Myomucosal Flap |

| LVP | Levator Veli Palatini |

| DOZ | Double Opposing Z-plasty |

| BMF | Buccal Mucosal Flap |

| BFPF | Buccal Fat Pad Flap |

| VPI | Velopharyngeal Insufficiency |

| VP | Velopharyngeal |

| ONF | Oro-nasal Fistulas |

| VPD | Velopharyngeal Dysfunction |

| TFP | Two-Flap Palatoplasty |

References

- Stuzin, J.M.; Wagstrom, L.; Kawamoto, H.K.; Baker, T.J.; Sa, W. The anatomy and clinical applications of the buccal fat pad. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1990, 85, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.K.; Han, W.; Kim, S.-G. The use of the buccal fat pad flap for oral reconstruction. Maxillofacial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2017, 39, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aycart, M.A.; Caterson, E.J. Advances in Cleft Lip and Palate Surgery. Medicina 2023, 59, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, C.C.T.; Yoo, J.; Busato, G.-M.; Franklin, J.H.; Fung, K.; Nichols, A.C. The buccinator flap: A review of current clinical applications. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011, 19, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.E.; Jackson, I.T.; Thomas, C. The evaluation of the use of the buccal myomucosal flap in cleft palate repair—A comparative study. Eur. J. Plast. Surg. 2010, 33, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossell-Perry, P. Flap necrosis after palatoplasty in patients with cleft palate. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 516375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logjes, R.J.; Aardweg, M.T.v.D.; Blezer, M.M.; van der Heul, A.M.; Breugem, C.C. Velopharyngeal insufficiency treated with levator muscle repositioning and unilateral myomucosal buccinator ap. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2016, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aziz, M. The use of buccal flap in the closure of posterior post-palatoplasty fistula. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2008, 72, 1657–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuli, P.; Parashar, A.; Nanda, V.; Sharma, R.K. Delayed buccal fat pad herniation: An unusual complication of buccal flap in cleft surgery. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2009, 42, 104–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi, B.; Kasten, S.J.; Buchman, S.R. Utilization of the buccal fat pad flap for congenital cleft palate repair. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009, 123, 1018–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, K.G.; Thurston, T.E.; Vercler, C.J.; Kasten, S.J.; Buchman, S.R. Harvesting the buccal fat pad does not result in aesthetic deformity in cleft patients: A retrospective analysis: A retrospective analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 140, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Cho, N.; Ahmed, M.; Ahmed, O.; Beg, M.S.A. The application of buccal fat pad to cover lateral palatal defect causes early mucolization. Cureus 2021, 13, e17532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotlarek, K.J.; Jaskolka, M.S.; Fang, X.; Ellis, C.; Blemker, S.S.; Horswell, B.; Kloostra, P.; Perry, J.L. A Preliminary Study of Anatomical Changes Following the Use of a Pedicled Buccal Fat Pad Flap During Primary Palatoplasty. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J. 2021, 59, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.-C.; Denadai, R.; Lin, H.-H.; Pai, B.C.-J.D.; Chu, Y.-Y.; Lo, L.-J.; Chou, P.-Y. Favorable transverse maxillary development after covering the lateral raw surfaces with buccal fat flaps in modified Furlow palatoplasty: A three-dimensional imaging-assisted long-term comparative outcome study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 150, 396e–405e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natsir-Kalla, D.-S.; Ruslin, M.; Alkaabi, S.A.; Yusuf, A.-S.-H.; Tajrin, A.; Forouzanfar, T.; Kuswanto, H.; Boffano, P.; Lo, L. Influence of patient-related factors on intraoperative blood loss during double opposing Z-plasty Furlow palatoplasty and buccal fat pad coverage: A prospective study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2022, 14, e608–e614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenssler, A.E.; Mann, R.; Gilbert, I.R.; Snodgrass, T.; Mann, S.; Kampfshulte, A.; Perry, J.L. Anatomical and physiological changes following primary palatoplasty using “The Buccal Flap Approach”. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J. 2023, 62, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulhassan, M.A.; Refahee, S.M.; Sabry, S.; Abd-El-Ghafour, M. Effects of two flap palatoplasty versus furlow palatoplasty with buccal myomucosal flap on maxillary arch dimensions in patients with cleft palate at the primary dentition stage: A cohort study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 5605–5613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal Lashin, M.; Kadry, W.; Al-Byale, R.R.; Beheiri, G. A novel technique predicting velopharyngeal insufficiency risk in newborns following primary cleft repair. A randomized clinical trial comparing buccinator flap and Bardach two-flap palatoplasty. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2024, 52, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, T.E.; Vargo, J.; Bennett, K.; Vercler, C.; Kasten, S.; Buchman, S. Filling the void: Use of the interpositional buccal fat pad to decrease palatal contraction and fistula formation. FACE 2020, 1, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saralaya, S.; Desai, A.K.; Ghosh, R. Buccal fat pad in cleft palate repair- An institutional experience of 27 cases. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 137, 110218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsherbiny, A.; Gelany, A.; Mazeed, A.S.; Mostafa, E.; Ahmed, M.A.; Allam, K.A.; Nabeih, A.A.N. Buccinator re-repair (BS + re: IVVP): A combined procedure to maximize the palate form and function in difficult VPI cases. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J. 2020, 57, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, J.S.; Sharma, S.; Jain, D.; Junval, J. Palatal lengthening by double opposing buccal flaps for surgical correction of velopharyngeal insufficiency in cleft patients. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2020, 48, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.M.; Park, H.; Oh, T.S. Use of a buccinator myomucosal flap and bilateral pedicled buccal fat pad transfer in wide palatal fistula repair: A case report. Arch. Craniofacial Surg. 2021, 22, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.N.; Fotouhi, A.R.; Grames, L.M.; Skolnick, G.B.; Snyder-Warwick, A.K.; Patel, K.B. Buccal myomucosal flap repair for velopharyngeal dysfunction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2023, 152, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitzman, T.J.; Perry, J.L.; Snodgrass, T.D.; Temkit, M.; Singh, D.J.; Williams, J.L. Comparative effectiveness of secondary Furlow and buccal myomucosal flap lengthening to treat velopharyngeal insufficiency. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.-Glob. Open 2023, 11, e5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboulhassan, M.A.; Elrouby, I.M.; Refahee, S.M.; Abd-El-Ghafour, M. Effectiveness of secondary furlow palatoplasty with buccal myomucosal flap in correction of velopharyngeal insufficiency in patients with cleft palate. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Choi, T.H.; Kim, S. Prospective study on the intraoperative blood loss in patients with cleft palate undergoing Furlow’s double opposing Z-palatoplasty. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J. 2018, 55, 954–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillies, T.; Homann, C.; Meyer, U.; Reich, A.; Joos, U.; Werkmeister, R. Perioperative complications in infant cleft repair. Head Face Med. 2007, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossell-Perry, P.; Schneider, W.J.; Gavino-Gutierrez, A.M. A comparative study to evaluate a simple method for the management of postoperative bleeding following palatoplasty. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2013, 40, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Strategy | Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“buccal fat pad” OR “buccal fat pad flap” OR “buccal myomucosal flap”) AND (“cleft palate” OR “cleft surgery” OR “cleft palate surgery” OR “primary palatal surgery” OR “secondary palatal surgery” OR “palatoplasty”) | 62 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY((“buccal fat pad” OR “buccal myomucosal flap”) AND (“cleft palate” OR “cleft palate surgery” OR “palatoplasty” OR “congenital cleft” OR “primary palatal surgery” OR “secondary palatal surgery”)) | 79 |

| Web of Science | (((TS = (buccal fat pad)) OR TS = (buccal myomucosal flap)) AND TS = (cleft palate)) | 93 |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Relevant topic Studies from the last 5 years (2020–2025) Studies published in English | Reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analysis Studies published before 2020 Animal model studies Other foreign languages |

| Reference | Publication Year | Study Design and Population | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Application of Buccal Fat Pad to Cover Lateral Palatal Defect Causes Early Mucolization [13] | 2021 | Prospective study 42 cleft palate patients | -buccal fat pad (BFP) effectively covers hard palate defects -BFP is easy to harvest with a low learning curve -epithelization rate is faster than conventional methods -minimal complications rates observed with BFP usage |

| A Preliminary Study of Anatomical Changes Following the Use of a Pedicled Buccal Fat Pad Flap During Primary Palatoplasty [14] | 2021 | Preliminary research study 15 children aged 3–7 years divided in 3 groups: 5 patients with cleft palate and/or lip who underwent primary palatoplasty with BFP flap, 5 patients received a traditional repair without addition of any tissue and 5 healthy non-cleft patients | -the pedicled BFP flap creates a longer velum -increased distance between posterior hard palate and levator veli palatini (LVP) muscle observed -larger effective velopharyngeal ratio compared to traditional techniques |

| Favourable Transverse Maxillary Development after Covering the Lateral Raw Surfaces with Buccal Fat Flaps in Modified Furlow Palatoplasty: A Three-Dimensional Imaging-Assisted Long-Term Comparative Outcome Study [15] | 2022 | Comparative study 22 patients with unilateral cleft lip, alveolus and palate in buccal fat flap group and 32 patients in Surgicel group | -covering lateral surfaces with buccal fat flaps reduces maxillary constriction -buccal fat flaps improve posterior transverse maxillary development -there was no increased complication rates observed with buccal fat flaps |

| Influence of patient-related factors on intraoperative blood loss during double opposing Z-plasty Furlow palatoplasty and buccal fat pad coverage: A prospective study [16] | 2022 | Prospective study 109 patients treated with DOZ Furlow palatoplasty and BFP graft | -DOZ Furlow palatoplasty with BFP graft is safe -higher weight increases intraoperative blood loss -longer operation time also increases blood loss -operate at an earlier age to reduce blood loss |

| Anatomical and Physiological Changes Following Primary Palatoplasty Using “The Buccal Flap Approach” [17] | 2023 | Prospective study 30 adult male patients divided into 2 groups: 15 males born with Veau type 3 or 4 and 15 healthy adults with no history of cleft palate | -the use of the buccal flap with DOZ palatoplasty had favourable soft tissue outcomes for adults with Veau type 3 and 4 clefts -the effective velar length was statistically longer in the buccal flap group compared to the control group |

| Effects of two-flap palatoplasty versus Furlow palatoplasty with buccal myomucosal flap on maxillary arch dimensions in patients with cleft palate at the primary dentition stage: a cohort study [18] | 2023 | Cohort 28 Participants | -Furlow palatoplasty with buccal myomucosal flap resulted in better maxillary arch dimensions in patients with cleft palate at the primary dentition stage. |

| A novel technique predicting velopharyngeal insufficiency risk in newborns following primary cleft repair. A randomized clinical trial comparing buccinator flap and Bardach two-flap palatoplasty [19] | 2024 | Randomized clinical trial 46 Participants | -reliable technique for primary management of cleft palate patients. -simple and easy technique with low donor site morbidity and low intra- and post-operative complications. -ability to be rotated and advanced in many directions with many patterns of orientation that help in closing wide palatal defects. -in primary repair of soft palate increases the palatal length. -velopharyngeal insufficiency prognosis is much better with BMF than with the Bardach two-flap palatoplasty technique. |

| Filling the Void: Use of the Interpositional Buccal Fat Pad to Decrease Palatal Contraction and Fistula Formation [20] | 2020 | Retrospective study 53 patients under age 3 who underwent primary palatoplasty utilizing a medially placed BFPF (buccal fat pad flap) | -BFPF improves cleft palate repair outcomes, reduces fistula formation and maintains palatal length -early results indicate excellent durability in cleft repairs |

| Reference | Publication Year | Study Design and Population | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buccal fat pad in cleft palate repair- An institutional experience of 27 cases [21] | 2020 | Retrospective study 27 cases of cleft lip and palate | -BFP is effective for cleft palate repair -BFP has high success rates with minimal morbidity |

| Buccinator Re-Repair (Bs + Re: IVVP): A Combined Procedure to Maximize the Palate Form and Function in Difficult VPI Cases [22] | 2020 | Prospective study 30 cases who had Bs + Re: IVVP (buccinator flaps’ lengthening and palate re-repair with radical intravelar veloplasty) | -buccinator re-repair is effective for VPI (velopharyngeal insufficiency) -significant improvement in speech postoperatively |

| Palatal lengthening by double opposing buccal flaps for surgical correction of velopharyngeal insufficiency in cleft patients [23] | 2020 | Prospective Study 50 Participants | -buccinator myomucosal flap can be used as an effective and safe method for lengthening the palate to correct VPI in patients of all ages. It can therefore be used as an alternative to Furlow Z plasty, before attempting potentially complicated procedures like pharyngoplasty |

| Use of a buccinator myomucosal flap and bilateral pedicled buccal fat pad transfer in wide palatal fistula repair: a case report [24] | 2021 | Case Report 1 Participant | -combination of a bilateral buccinator myomucosal flap and pedicled BFP transfer was a feasible and cost-effective technique. -The patient required long-term follow-up to monitor his speech development and palate growth. -Therefore, a posteriorly based buccinator myomucosal flap might be considered to close large ONFs and improve VPI in young patients with cleft palate. |

| Buccal Myomucosal Flap Repair for Velopharyngeal Dysfunction [25] | 2022 | Retrospective Study 25 participants | -Secondary palatoplasty incorporating buccal myomucosal flaps is a safe and effective option for the treatment of VPD, improving postoperative speech outcomes. |

| Comparative Effectiveness of Secondary Furlow and Buccal Myomucosal Flap Lengthening to Treat Velopharyngeal Insufficiency [26] | 2023 | Retrospective Study 32 Participants | -both procedures significantly increased velar length and effective velar length and decreased hypernasality by two scalar points. |

| Effectiveness of secondary furlow palatoplasty with buccal myomucosal flap in correction of velopharyngeal insufficiency in patients with cleft palate [27] | 2024 | Cohort 23 Participants | -BMMF with Furlow palatoplasty was successful in improving hypernasality, speech intelligibility, and nasopharyngoscopic scores in patients with cleft palate. -might be a surgical procedure with noticeable benefits while treating patients suffering from VPI after cleft palate repair. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Armencea, G.; Reddy, G.S.; Bran, S.; Bereanu, A.; Anton, D.; Onișor, F.; Dinu, C.-M.; Papuc, A.D.; Stoia, S.; Tamaș, T.; et al. The Use of Buccal Fat Pad Versus Buccal Mucosal Flap in Cleft Patient Palatoplasty—A Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3114. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093114

Armencea G, Reddy GS, Bran S, Bereanu A, Anton D, Onișor F, Dinu C-M, Papuc AD, Stoia S, Tamaș T, et al. The Use of Buccal Fat Pad Versus Buccal Mucosal Flap in Cleft Patient Palatoplasty—A Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(9):3114. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093114

Chicago/Turabian StyleArmencea, Gabriel, Gosla Srinivas Reddy, Simion Bran, Alexandru Bereanu, Damaris Anton, Florin Onișor, Cristian-Mihail Dinu, Alexandra Denisa Papuc, Sebastian Stoia, Tiberiu Tamaș, and et al. 2025. "The Use of Buccal Fat Pad Versus Buccal Mucosal Flap in Cleft Patient Palatoplasty—A Literature Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 9: 3114. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093114

APA StyleArmencea, G., Reddy, G. S., Bran, S., Bereanu, A., Anton, D., Onișor, F., Dinu, C.-M., Papuc, A. D., Stoia, S., Tamaș, T., & Băciuț, M.-F. (2025). The Use of Buccal Fat Pad Versus Buccal Mucosal Flap in Cleft Patient Palatoplasty—A Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(9), 3114. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093114