Disparities in Pain Evaluation and Treatment During Labor: A Racial and Ethnic Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

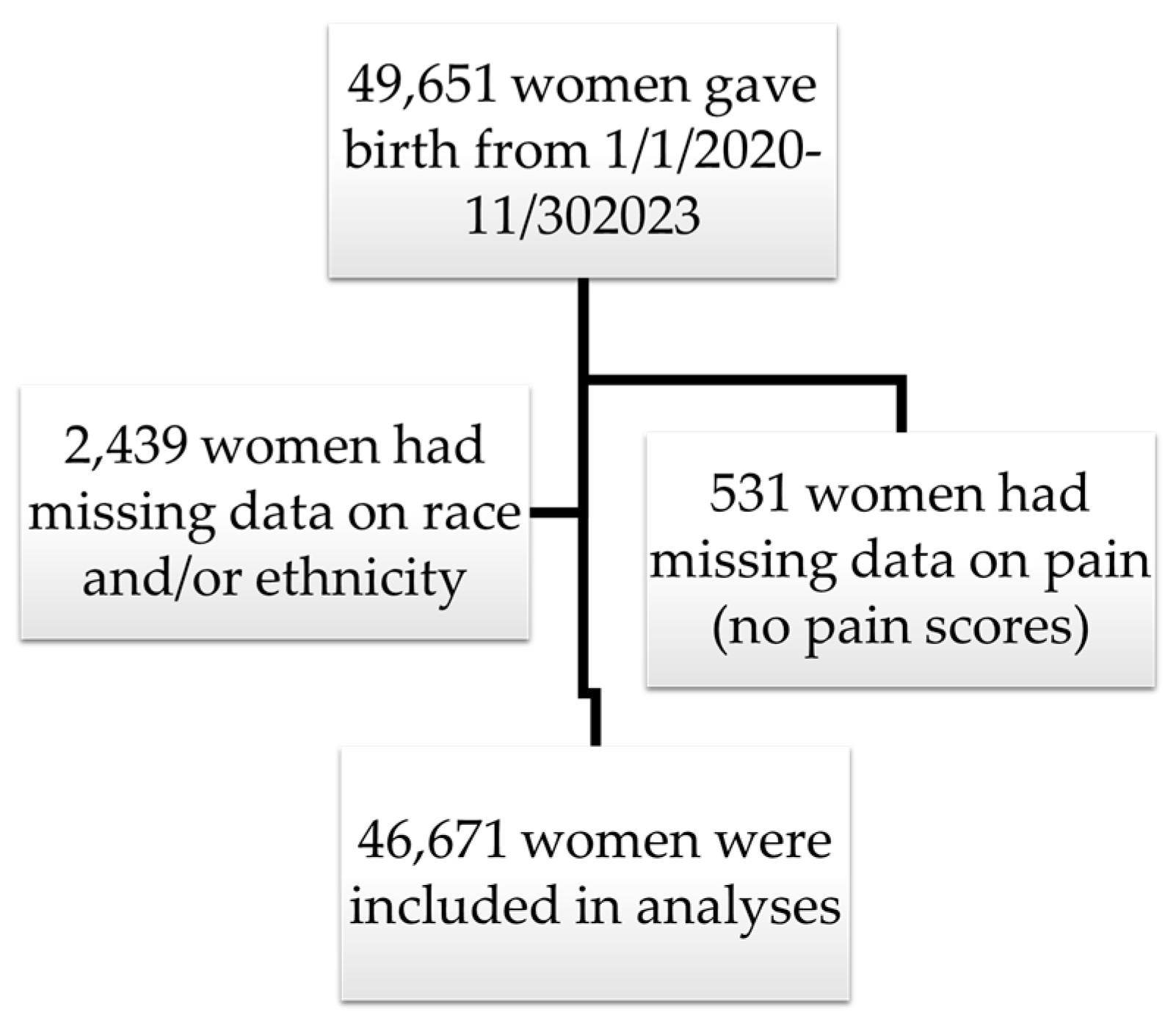

2.2. Participants

2.3. Variables and Data Sources

Pain Variables

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Inferential Statistics

3.2. Univariate General Linear Model (GLM) for Relationship Between Race/Ethnicity and Pain Scores

3.3. Differences in Pain Treatment

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lowe, N.K. The nature of labor pain. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186, S16–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenach, J.C.; Pan, P.H.; Smiley, R.; Lavand’homme, P.; Landau, R.; Houle, T.T. Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain 2008, 140, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Troendle, J.; Mikolajczyk, R.; Sundaram, R.; Beaver, J.; Fraser, W. The natural history of the normal first stage of labor. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 115, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Cooley, C.; Ziadni, M.S.; Mackey, I.; Flood, P. Association between history of childbirth and chronic, functionally significant back pain in later life. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.S.; Agarthesh, T.; Tan, C.W.; Sultana, R.; Chen, H.Y.; Chua, T.E.; Sng, B.L. Perceived stress during labor and its association with depressive symptomatology, anxiety, and pain catastrophizing. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, V.A.; Nyman, T.; Nanavaty, N.; George, N.; Brooker, R.J. Trajectories of pain during pregnancy predict symptoms of postpartum depression. PAIN Rep. 2021, 6, e933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobson, J.M.; Moody, M.D.; Sorge, R.E.; Goodin, B.R. The neurobiology of social stress resulting from Racism: Implications for pain disparities among racialized minorities. Neurobiol. Pain 2022, 12, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, V.A.; Trost, Z.; Ezenwa, M.O.; Sturgeon, J.A.; Hood, A.M. Mechanisms of injustice: What we (do not) know about racialized disparities in pain. Pain 2022, 163, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajacova, A.; Grol-Prokopczyk, H.; Zimmer, Z. Sociology of Chronic Pain. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2021, 62, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badreldin, N.; Ditosto, J.D.; Grobman, W.A.; Yee, L.M. Maternal psychosocial factors associated with postpartum pain. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 100908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.A.; Nahin, R.L. Cross-Sectional Analyses of High-Impact Pain Across Pregnancy Status by Race and Ethnicity. J. Women’s Health 2022, 31, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badreldin, N.; Grobman, W.A.; Yee, L.M. Racial Disparities in Postpartum Pain Management. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.; Schulman, M. Race inequality in epidural use and regional anesthesia failure in labor and birth: An examination of women’s experience. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2014, 5, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.D.; Asiodu, I.V.; McKenzie, C.P.; Tucker, C.; Tully, K.P.; Bryant, K.; Verbiest, S.; Stuebe, A.M. Racial and Ethnic Inequities in Postpartum Pain Evaluation and Management. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, S.Q.; Bartley, E.J.; Powell-Roach, K.; Palit, S.; Morais, C.; Thompson, O.J.; Cruz-Almeida, Y.; Fillingim, R.B. The Imperative for Racial Equality in Pain Science: A Way Forward. J. Pain 2021, 22, 1578–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, W. A 2020 Census Portrait of America’s Largest Metro Areas: Population growth, diversity, segregation, and youth. Policy Briefs and Reports. 2022. Available online: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/brookings_policybriefs_reports/11 (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Strait, J.B.; Gong, G. Ethnic Diversity in Houston, Texas: The Evolution of Residential Segregation in the Bayou City, 1990–2000. Popul. Rev. 2010, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaferi, A.A.; Schwartz, T.A.; Pawlik, T.M. STROBE Reporting Guidelines for Observational Studies. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, 577–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagan, K.; Javed, Z.; Cainzos-Achirica, M.; Elizondo, J.V.; Nicolas, C.; Yahya, T.; Acquah, I.; Blankstein, R.; Hyder, A.; Mossialos, E.; et al. Abstract 11803: Area Deprivation and COVID-19 Outcomes in Patients With and Without Cardiovascular Disease: The Curator Registry of Houston Methodist. Circulation 2021, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahidy, F.; Jones, S.L.; Tano, M.E.; Nicolas, J.C.; Khan, O.A.; Meeks, J.R.; Pan, A.P.; Menser, T.; Sasangohar, F.; Naufal, G.; et al. Rapid Response to Drive COVID-19 Research in a Learning Health Care System: Rationale and Design of the Houston Methodist COVID-19 Surveillance and Outcomes Registry (CURATOR). JMIR Med. Inform. 2021, 9, e26773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0.2.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vedam, S.; Stoll, K.; Taiwo, T.K.; Rubashkin, N.; Cheyney, M.; Strauss, N.; McLemore, M.; Cadena, M.; Nethery, E.; Rushton, E.; et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: Inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callister, C.; Khalaf, I.; Semenic, S.; Kartchner, R.; Vehvilainen-Julkunen, K. The pain of childbirth: Perceptions of culturally diverse women. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2003, 4, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saluja, B.; Bryant, Z. How Implicit Bias Contributes to Racial Disparities in Maternal Morbidity and Mortality in the United States. J. Women’s Health 2021, 30, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, M.; Kharazmi, N.; Lim, E. Traditional beliefs and practices in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum: A review of the evidence from Asian countries. Midwifery 2018, 56, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, R.; Ando, K.; Flood, P.D. Factors associated with persistent pain after childbirth: A narrative review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2020, 124, e117–e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampton, S.B. The Influence of Race and Gender on Nursing Pain Management Decisions; Texas Woman’s University: Denton, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Njoku, A.; Evans, M.; Nimo-Sefah, L.; Bailey, J. Listen to the Whispers before They Become Screams: Addressing Black Maternal Morbidity and Mortality in the United States. Healthcare 2023, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, B.K.; Vuletich, H.A.; Lundberg, K.B. The bias of crowds: How implicit bias bridges personal and systemic prejudice. Psychol. Inq. 2017, 28, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.L.; Zapata, J.Y.; Brown, H.W.; Hagiwara, N. Rethinking Bias to Achieve Maternal Health Equity: Changing Organizations, Not Just Individuals. Obs. Gynecol. 2021, 137, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cronin, K.A.; Howlader, N.; Stevens, J.L.; Trimble, E.L.; Harlan, L.C.; Warren, J.L. Racial disparities in the receipt of guideline care and cancer deaths for women with ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray-Griffith, S.L.; Wendel, M.P.; Stowe, Z.N.; Magann, E.F. Chronic pain during pregnancy: A review of the literature. Int. J. Women’s Health 2018, 2018, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathawa, C.A.; Arora, K.S.; Zielinski, R.; Low, L.K. Perspectives of doulas of color on their role in alleviating racial disparities in birth outcomes: A qualitative study. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2022, 67, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westgren, M.; Pettersson, K.; Hagberg, H.; Acharya, G. Severe maternal morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19: The risk should not be downplayed. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020, 99, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Race or Ethnicity Identification (Self-Report) | N | Mean Pain Rating | Std. Deviation of Pain Rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | 5002 | 1.6783 | 1.12186 |

| Black | 8358 | 1.8322 | 1.29719 |

| Hispanic White | 13,557 | 1.7694 | 1.19172 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 17,873 | 1.7663 | 1.17354 |

| Hawaiian-Pacific Islander | 136 | 1.8049 | 1.39855 |

| Multiracial | 1182 | 1.6312 | 1.25976 |

| Native American | 462 | 1.8681 | 1.29773 |

| Other | 108 | 1.6372 | 1.51495 |

| Total | 46,678 | 1.7670 | 1.20241 |

| Average Pain Score During Admission 1 | Race/Ethnicity 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | F | p | |

| Age at delivery | −0.010 | 0.039 | 297.43 | <0.001 * |

| Length of stay (in hours) | 0.014 | 0.003 | 17.37 | <0.001 * |

| Cesarean Delivery | 0.105 | <0.001 * | 15.03 | <0.001 * |

| Factor | Type III SS | F | p-Value |

| Corrected model | 875.83 | 61.36 | <0.001 * |

| Intercept | 3135.31 | 2196.65 | <0.001 * |

| Age | 33.27 | 23.31 | <0.001 * |

| LOS | 9.10 | 6.37 | 0.012 |

| Cesarean Delivery | 760.28 | 532.66 | <0.001 * |

| Race/Ethnicity | 81.04 | 8.11 | <0.001 * |

| Contrasts (M, SD) | Contrast Estimate | CI | p-Value |

| Non-Hispanic White (1.77, 1.17) | Reference group | n/a | n/a |

| Black (1.83, 1.29) | 0.052 | 0.020–0.083 | <0.001 * |

| Hispanic White (1.77, 1.19) | 0.000 | −0.026–0.027 | 0.976 |

| Asian (1.68, 1.12) | −0.081 | −0.118–0.043 | <0.001 * |

| Hawaiian-Pacific Islander (1.80, 1.40) | 0.061 | −0.141–−0.262 | 0.555 |

| Multiracial (1.63, 1.26) | −0.137 | −0.207–−0.067 | <0.001 * |

| Native American (1.87, 1.30) | 0.083 | −0.027–0.194 | 0.140 |

| Other (1.64, 1.51) | −0.143 | −0.369–0.083 | 0.214 |

| Factor | Type III SS | F | p-Value |

| Corrected model | 85.086 | 634.40 | <0.001 * |

| Intercept | 5.013 | 411.12 | <0.001 * |

| Age | 0.741 | 60.79 | <0.001 * |

| LOS | 1.151 | 94.43 | <0.001 * |

| Cesarean Delivery | 20.936 | 1717.09 | <0.001 * |

| Average pain score | 51.303 | 4207.67 | <0.001 * |

| Race/Ethnicity | 5.68 | 66.57 | <0.001 * |

| Contrasts (M, SD) | Contrast Estimate | CI | p-Value |

| Non-Hispanic White (0.130, 1.22) | Reference group | n/a | n/a |

| Black (0.111, 0.118) | −0.023 | (−0.025, −0.020) | <0.001 * |

| Hispanic White (0.121, 0.115) | −0.009 | (−0.012, −0.007) | <0.001 * |

| Asian (0.130, 0.115) | 0.004 | (0.001−0.008) | 0.018 |

| Hawaiian-Pacific Islander (0.117, 0.129) | −0.009 | (−0.028, 0.009) | 0.321 |

| Multiracial (0.085, 0.111) | −0.040 | (−0.047, −0.034) | <0.001 * |

| Native American (0.140, 0.120) | 0.004 | (−0.006, 0.015) | 0.397 |

| Other (0.037, 0.080) | −0.092 | (−0.113, −0.071) | <0.001 * |

| Factor | Type III SS | F | p-Value |

| Corrected model | 9.319 | 161.13 | <0.001 ** |

| Intercept | 0.699 | 133.01 | <0.001 ** |

| Age | 0.087 | 16.50 | <0.001 ** |

| LOS | 0.034 | 6.43 | 0.011 |

| Cesarean Delivery | 0.33 | 62.58 | <0.001 ** |

| Average pain score | 7.61 | 1447.57 | <0.001 ** |

| Race/Ethnicity | 1.003 | 27.26 | <0.001 ** |

| Contrasts (M, SD) | Contrast Estimate | CI | p-Value |

| Non-Hispanic White (0.045, 0.073) | Reference group | n/a | n/a |

| Black (0.044, 0.076) | −0.002 | (−0.004, 0.000) | 0.083 |

| Hispanic White (0.043, 0.072) | −0.002 | (−0.004, −0.001) | 0.005 * |

| Asian (0.054, 0.079) | 0.011 | (0.009, 0.013) | <0.001 ** |

| Hawaiian-Pacific Islander (0.035, 0.065) | −0.010 | (−0.022, 0.003) | 0.125 |

| Multiracial (0.033, 0.067) | −0.010 | (−0.015, −0.006) | <0.001 ** |

| Native American (0.055, 0.082) | 0.008 | (0.001, 0.015) | 0.017 |

| Other (0.006, 0.026) | −0.037 | (−0.051, −0.023) | <0.001 ** |

| Factor | Type III SS | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected model | 0.008 | 20.13 | <0.001 ** |

| Intercept | 0.001 | 22.08 | <0.001 ** |

| Age | 0.001 | 16.75 | <0.001 ** |

| LOS | 0.000 | 8.01 | 0.005 * |

| Cesarean Delivery | 0.003 | 77.43 | <0.001 ** |

| Average pain score | 0.004 | 111.70 | <0.001 ** |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.000 | 1.54 | 0.148 |

| Factor | Type III SS | F | p-Value |

| Corrected model | 8.73 | 91.59 | <0.001 ** |

| Intercept | 3.09 | 356.89 | <0.001 ** |

| Age | 0.16 | 18.51 | <0.001 ** |

| LOS | 0.48 | 55.55 | <0.001 ** |

| Cesarean Delivery | 0.15 | 17.26 | <0.001 ** |

| Average pain score | 4.54 | 523.81 | <0.001 ** |

| Race/Ethnicity | 3.54 | 58.41 | <0.001 ** |

| Contrasts (M, SD) | Contrast Estimate | CI | p-Value |

| Non-Hispanic White (0.056, 0.087) | Reference group | n/a | n/a |

| Black (0.060, 0.096) | 0.004 | (0.001, 0.006) | <0.001 ** |

| Hispanic White (0.061, 0.095) | 0.004 | (0.002, 0.006) | <0.001 ** |

| Asian (0.082, 0.108) | 0.027 | (0.024, 0.030) | <0.001 ** |

| Hawaiian-Pacific Islander (0.059, 0.093) | 0.003 | (−0.013, 0.019) | 0.715 |

| Multiracial (0.043, 0.080) | −0.012 | (−0.018, −0.007) | <0.001 ** |

| Native American (0.070, 0.102) | 0.013 | (0.004, 0.022) | 0.003 * |

| Other (0.010, 0.031) | −0.045 | (−0.062, −0.027) | <0.001 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vasquez, N.N.; Ramirez, P.T.; Bautista, C.; Madan, A.; Rohr, J.C. Disparities in Pain Evaluation and Treatment During Labor: A Racial and Ethnic Perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093097

Vasquez NN, Ramirez PT, Bautista C, Madan A, Rohr JC. Disparities in Pain Evaluation and Treatment During Labor: A Racial and Ethnic Perspective. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(9):3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093097

Chicago/Turabian StyleVasquez, Namrata N., Pedro T. Ramirez, Chandra Bautista, Alok Madan, and Jessica C. Rohr. 2025. "Disparities in Pain Evaluation and Treatment During Labor: A Racial and Ethnic Perspective" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 9: 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093097

APA StyleVasquez, N. N., Ramirez, P. T., Bautista, C., Madan, A., & Rohr, J. C. (2025). Disparities in Pain Evaluation and Treatment During Labor: A Racial and Ethnic Perspective. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(9), 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093097